In the 2016 presidential election, Hillary Clinton’s campaign ran an ad that featured young children watching the Republican nominee, Donald Trump, make a series of offensive and sexist comments (Corasaniti Reference Corasaniti2016). The ad’s message was simple: children are watching and learning. What the ad does not draw out explicitly is that children are watching and learning about gender, politics, and how they interact. Nor does the ad highlight that this learning takes place in varied ways and contexts: elementary school students studying American presidents and the founding fathers, classroom discussions of women’s contributions during Women’s History month, or children watching news about current events and political leaders. In this article, we examine whether and how girls and boys see politics as gendered. Motivating this investigation is the question of whether women’s depressed interest in politics and running for political office (Clayton, O’Brien, and Piscopo Reference Clayton, O’Brien and Piscopo2019; Thomsen and King Reference Thomsen and King2020) is rooted in lifelong socialization processes that point them away from politics. We advance and test a new theoretical framework we call gendered political socialization, which links established literatures on children’s gender socialization and political socialization as two intersecting processes of a child’s experience. We look for evidence of gendered political socialization and its constituent processes in novel data from interviews and surveys of more than 1,600 US children in grades 1–6 across four research locations (Bos et al. Reference Bos, Greenlee, Holman, Oxley and Lay2021).

We document that traditional gender socialization, where children internalize gender stereotypes and learn to conform to the expectations for their sex (Letendre Reference Letendre2007; Liben et al. Reference Liben, Bigler, Ruble, Martin and Powlishta2002), manifests in children’s choice of careers.Footnote 1 At the same time, political socialization occurs, where children are exposed to political topics via a variety of agents and develop more complex ideas about politics as they grow older (Cook Reference Cook1985; Greenstein Reference Greenstein1965; Sapiro Reference Sapiro2004; Stoker and Bass Reference Stoker, Bass, Shapiro and Jacobs2011). Here, we show that with age and increased exposure, children report more awareness about politics.

Operating together, gender socialization and political socialization produce what we call gendered political socialization, wherein children infer that politics is for men and girls infer that political roles conflict with their defined gender roles. We theorize that these sex differences emerge because when children learn about the political world, they learn that this domain is male-dominated and masculine (Cassese, Bos, and Schneider Reference Cassese, Bos and Schneider2014; Lay et al. Reference Lay, Holman, Bos, Greenlee, Oxley and Buffett2021). We develop and present promising empirical measures, including an innovative measure of gendered views of political leadership, the Draw a Political Leader (DAPL) task. While we focus on the political domain, we highlight similar dynamics documented in science, technology, engineering, and math (STEM). Finally, we find that as they age, girls are less likely to depict women as leaders and tend to express lower levels of political interest or ambition than do boys.

Our study of children’s political attitudes responds to the oft-noted need to better understand political socialization (Sapiro Reference Sapiro2004; Stoker and Bass Reference Stoker, Bass, Shapiro and Jacobs2011), contributes to efforts to recognize moments of political change and development across the life course, and improves our understanding of the origins of deeply rooted and politically consequential attitudes related to the socialization of gender and race (Bauer Reference Bauer2020; DeSante and Smith Reference DeSante and Smith2019). Further, while European scholars have returned to the study of children’s socialization to politics (e.g., Haug Reference Haug2017; van Deth, Abendschön, and Vollmar Reference van Deth, Abendschön and Vollmar2011), there is a dearth of recent data collected from young children in the United States. This is despite a latent recognition that childhood is an important site of political development.

We present compelling evidence for gendered political socialization and its components and document the negative effects of this process for girls. The sex differences we observe, where girls have less political interest and ambition than boys and that this gap increases with age, are reflected in well-documented adult differences between men and women on these indicators. As these differences contribute to women’s descriptive underrepresentation in politics (Crowder-Meyer Reference Crowder-Meyer2020; O’Brien and Rickne Reference O’Brien and Rickne2016), it is essential to identify how and when these and other differences between boys and girls emerge during childhood and to develop evidence-based approaches to reduce the observed gaps. Because we show that girls are more likely to “opt out” of politics at an early age, this means that without intervention their voices will not be heard, maintaining sex-based inequality in our political system.

Gender Socialization and Political Socialization

The process of gendered political socialization lies at the not-yet-theorized intersection of two well-established processes: gender socialization and political socialization. Gendered political socialization involves both the internalization of gender roles and norms among children and learning about and being socialized to the political world. Here, we lay out these constituent socialization processes and how we will test them with our data on young children.

The first component of gendered political socialization is gender socialization, a process well-documented by decades of social psychological research. This process powerfully influences child development, leading young people to internalize gender concepts and gender stereotypes at early ages (Letendre Reference Letendre2007; Liben et al. Reference Liben, Bigler, Ruble, Martin and Powlishta2002). The foundational social role theory holds that children create gendered associations through observing men and women in differentiated social roles, for example, women in caregiving roles such as nurses and men in leadership roles such as managers (Bigler and Liben Reference Bigler and Liben1990; Eagly, Wood, and Diekman Reference Eagly, Wood, Diekman, Eckes and Trautner2000). Gender socialization reinforces perceptions of the roles men and women are best suited to hold, the traits they need to be successful in those roles, and whether the roles will allow them to achieve their gender-related goals (Diekman et al. Reference Diekman, Brown, Johnston and Clark2010; Diekman and Steinberg Reference Diekman and Steinberg2013; Diekman et al. Reference Diekman, Steinberg, Brown, Belanger and Clark2017).

Evidence is plentiful that children internalize gender stereotypes and conform to gendered expectations. Children mimic a gendered division of labor and express gendered preferences in toys, activities, job aspirations, and assigned chores (Etaugh and Liss Reference Etaugh and Liss1992). Girls develop traits in line with gender roles (e.g., girls value nurturance versus competitiveness) (Eagly et al. Reference Eagly, Diekman, Johannesen-Schmidt and Koenig2004), demonstrate an emphasis on being more care oriented than boys (Cicognani et al. Reference Cicognani, Zani, Fournier, Gavray and Born2012; Jaffee and Hyde Reference Jaffee and Hyde2000), and show less interest in pursuing interests and roles that conflict with defined gender roles (Bian, Leslie, and Cimpian Reference Bian, Leslie and Cimpian2017; Rudman and Phelan Reference Rudman and Phelan2010; Weisgram Reference Weisgram2016). While the effects of gendered socialization can be direct (Eccles et al. Reference Eccles, Freedman-Doan, Frome, Jacobs, Yoon, Eckes and Trautner2000), they can also operate indirectly. For example, gendered expectations at school around academic achievement can then shape children’s orientations toward future careers (Morris Reference Morris2012).

We investigate one dimension of gender socialization by asking children a question about their level of interest in different professions. Given past research, we anticipate that girls will express higher levels of interest in being a teacher or a doctor, due to the centrality of caring as a trait associated with those roles. Similarly, we expect that boys will express high levels of interest in professions like police chief or business owner that embody male typical traits, such as being assertive (Hypothesis 1). Further, these gendered occupation choices should strengthen with age (Hypothesis 2).

Political socialization occurs in tandem to gender socialization. This lifelong process of political learning and the development of values and beliefs related to politics, government, and political leadership begins in childhood (Greenstein Reference Greenstein1965; Merelman Reference Merelman and Hermann1986; Sapiro Reference Sapiro2004). As they grow up, children develop more complex understandings of political leaders and the political domain (Carter and Teten Reference Carter and Teten2002; Greenstein Reference Greenstein1965; Hess and Easton Reference Hess and Easton1960; Oxley et al. Reference Oxley, Holman, Greenlee, Bos and Lay2020; Sigel Reference Sigel1968). Early socialization scholarship argued these changes in children’s perceptions of politics as they age were the result of increasingly complex political conversations with parents at home (Easton, Dennis, and Easton Reference Easton, Dennis and Easton1969; Greenstein Reference Greenstein1965) and increased exposure to politics and campaigns via the mass media (Gimpel, Lay, and Schuknecht Reference Gimpel, Lay and Schuknecht2003; Hess and Torney Reference Hess and Torney1968; Sears and Valentino Reference Sears and Valentino1997). Additionally, as they progress through school, children are increasingly exposed to politics through social studies and civics curricula (Campbell and Niemi Reference Campbell and Niemi2016; Neundorf, Niemi, and Smets Reference Neundorf, Niemi and Smets2016).

We test children’s awareness of politics with survey questions about their exposure to politically relevant content and via a drawing task. As evidence of the political socialization process, we expect that older children will be more likely to draw political figures, to include political activities in their drawings, and to report higher levels of exposure to political content in their curriculum and extracurricular activities (Hypothesis 3).

Gendered Political Socialization

While both gender socialization and political socialization are well theorized and empirically tested, a critical gap exists in understanding their intersection. The two processes do not run parallel to one another, but rather, they intersect and influence each other in a process we call gendered political socialization. This process is likely to communicate to children that boys are compatible with political leadership roles and that girls are not. We argue and test whether these coinciding processes both (1) shape children’s perceptions such that politics is a masculine domain and political leaders are more likely to be men and (2) result in girls perceiving a mismatch between their gendered expectations and with exploring politics or pursuing political roles.

Through gender socialization, children learn what society deems are sex appropriate traits, and this has implications for political socialization. For instance, via school curricula, children learn that politics centers on conflict and competition (e.g., wars and elections), characteristics associated with masculinity (Cassese and Holman Reference Cassese and Holman2018; Oliver and Conroy Reference Oliver and Conroy2020). School-based “political” activities also highlight competitive contests, such as student council elections, mock trial, and debate teams. Children’s social studies curricula emphasize men’s contributions to US politics (Lay et al. Reference Lay, Holman, Bos, Greenlee, Oxley and Buffett2021; Schocker and Woyshner Reference Schocker and Woyshner2013),Footnote 2 and stereotypes of leaders focus more on male-typical traits like being a strong leader and being assertive (Bauer Reference Bauer2020; Holman, Merolla, and Zechmeister Reference Holman, Merolla and Zechmeister2021; Koenig et al. Reference Koenig, Eagly, Mitchell and Ristikari2011) that overlap greatly with agentic stereotypes of men (Eagly, Wood, and Diekman Reference Eagly, Wood, Diekman, Eckes and Trautner2000).Footnote 3 Additionally, media coverage confirms that men hold most political leadership roles in the United States (Center for American Women and Politics 2021); shows that these men engage in power-seeking behaviors as opposed to collaborative, cooperative, and communal-oriented behaviors (Schneider et al. Reference Schneider, Holman, Diekman and McAndrew2016); and characterizes conflict, scandal, and gridlock as central features of the political process.

We draw from a large literature on STEM fields that demonstrates persistent gender-stereotypic perceptions of scientists among children. As previously mentioned, we know that as children observe adults in particular roles, whether in person, in school textbooks, or in the media, they make stereotypic inferences about who is best suited to take on those roles. These inferences include stereotypes such that children are more likely to connect the role of scientist with men (e.g., Miller et al. Reference Miller, Nolla, Eagly and Uttal2018), in part due to their traditionally seeing few women in scientific roles (Ceci et al. Reference Ceci, Ginther, Kahn and Williams2014). Indeed, over 50 years of being asked to “draw a scientist,” children mostly draw men (Miller et al. Reference Miller, Nolla, Eagly and Uttal2018). Additionally, stereotypes of scientists in these drawings are dominated by agentic stereotypes of men (e.g., independent, competitive) and not with communal stereotypes of women (e.g., helpful, caring) (Carli et al. Reference Carli, Alawa, Lee, Zhao and Kim2016). Children as young as six years old hold gender-based scientist stereotypes (Bian, Leslie, and Cimpian Reference Bian, Leslie and Cimpian2017). More broadly, children do not perceive STEM careers to afford opportunities to achieve communal goals (Diekman et al. Reference Diekman, Brown, Johnston and Clark2010), stereotypes that are reinforced by parents and teachers whose own sex-based expectations encourage boys, but not girls, toward STEM education and careers (Gunderson et al. Reference Gunderson, Ramirez, Levine and Beilock2012).

There are obvious parallels with the domain of politics. Agents of both gender and political socialization reinforce children’s perceptions of politics as a masculine domain, where political roles afford opportunities to achieve agentic but not communal goals (Schneider et al. Reference Schneider, Holman, Diekman and McAndrew2016), political institutions are “strongly associated with men and masculinity” (Duerst-Lahti Reference Duerst-Lahti, Carroll and Fox2006, 15), and an “embedded masculinity” is present in electoral politics (Dittmar Reference Dittmar2015, 6). Put simply, messages about the political domain, coming from multiple sources, communicate to children that politics is for boys. Thus, gendered political socialization provides a framework in which to investigate how young children integrate beliefs about sex and gender in their understandings of the political world.

Gendered Perceptions of Political Leaders

One indicator of gendered political socialization that we seek to observe in this study is the extent to which gender shapes children’s perceptions of political leadership. To understand children’s gendered views of the political world, we present the Draw a Political Leader (DAPL) task as an innovative new tool to shed light on whether and how children perceive political leadership as gendered. Our DAPL task is an adaptation of the Draw a Scientist Task (DAST) used by STEM scholars. By allowing children to make use of a familiar medium of self-expression (i.e., drawing), we can glean insights into aspects of gender that young children may not have the language to fully express. We use this tool to examine the degree to which children disproportionately perceive political leaders as men and as having masculine traits.

Examining perceptions of political leaders from a variety of ages also allows us to see whether increased levels of learning about political systems and political actors are related to an increase in male stereotypic depictions of political leaders. In STEM, when asked to draw a scientist, clear majorities of six-year-old boys and girls drew a scientist of their own sex (Miller et al. Reference Miller, Nolla, Eagly and Uttal2018), as they know little about scientists (Newton and Newton Reference Newton and Newton1992). However, as students gain exposure to the sciences through schooling and the media, their male-science stereotypes strengthen and the probability of drawing a male scientist also increases (Miller et al. Reference Miller, Nolla, Eagly and Uttal2018). We theorize a similar pattern regarding politics. As children grow up, they learn about and internalize aspects of both gender and political socialization, learn more about what is appropriate for women and men, and develop attitudes and predilections about politics. These processes intersect so that children come to believe that politics is a domain more suitable for men than women. We thus anticipate that most children will draw men as political leaders, but that girls will be more likely to draw women as leaders than will boys (Hypothesis 4). We also expect that as children age (and become more attuned to the sex imbalance within politics), they will be less likely to draw women as political leaders and more likely to depict political leaders with masculine traits (Hypothesis 5).

Sex Differences in Political Interest and Ambition

Finally, we contend that gendered political socialization results in differences between boys and girls in two areas: political interest and political ambition. Our focus on children expands existing understanding of sex differences in political interest. Across multiple studies, contexts and periods, scholars have repeatedly found that women and adolescent girls have lower levels of political interest than men and boys (Fraile and Sánchez-Vítores Reference Fraile and Sánchez-Vítores2020; Kittilson and Schwindt-Bayer Reference Kittilson and Schwindt-Bayer2012; Sánchez-Vítores Reference Sánchez-Vítores2019). The emergence of these sex differences in youth suggest that gendered socialization drives this gap, not resource disparities that occur later in life.

While scholars have not yet documented sex differences in political interest among young children, some research hints at them. Parents are less likely to engage in conversation about politics with girls compared with boys (Campbell and Wolbrecht Reference Campbell and Wolbrecht2006; Lawless and Fox Reference Lawless and Fox2015), and those conversations are a key determinant of girls’ political interest (Campbell and Wolbrecht Reference Campbell and Wolbrecht2006).Footnote 4 Similarly, scholars have documented a sex difference in political ambition for adults, but far less is known about young children. The youngest respondents in prior studies have been ages 13–15 (Elder Reference Elder2004; Hooghe and Dassonneville Reference Hooghe and Dassonneville2013; Lawless and Fox Reference Lawless and Fox2015) and while scholars have found sex differences within this age range, the results have been mixed. Nonetheless, there is evidence that girls’ political ambition is lower than that of boys beginning in adolescence (Hooghe and Dassonneville Reference Hooghe and Dassonneville2013) and more evidence that this gap exists during the college years (Elder Reference Elder2004; Lawless and Fox Reference Lawless and Fox2015). Based on gendered political socialization, we expect girls to report lower levels of political interest and political ambition than boys and that these differences increase as children age and are socialized into gender and political roles (Hypothesis 6).

Methodology

To test our expectations, in late 2017 and early 2018, we interviewed and surveyed children in grades 1–6 at four research locations throughout the nation: greater Boston, upstate New York, northeastern Ohio, and New Orleans. As we planned to recruit children, a vulnerable population, we took great care to ensure that our research process offered layers of protection that included active—rather than passive—informed consent from parents as well as assent from each child participant. We received human-subjects approval from our home institutions that reflected this. We each requested permission to conduct our study from superintendents or principals in public school districts and private schools. After receiving administrator permission and, for some districts, identifying the schools where we would collect data, we scheduled dates to visit each school to collect data with children during the school day. In the meantime, we sought parental permission for their child(ren) to participate. For those students whose parents consented, the researcher read an age-appropriate consent script and then asked for each child’s verbal assent to participate in the study.

Our sample consists of 1,604 children across 18 schools (14 public and 4 private). Ours constitutes a purposive sample that is not representative of a larger population. However, the schools vary by racial and ethnic composition, geographic location, socioeconomic status, and urban/suburban/rural location. Notably, across these schools, there is considerable variation in racial and ethnic diversity and economic disadvantage (measured as the percentage of students receiving free or reduced-price lunches). Compared with national averages, the public schools in our sample enroll more white, fewer Latino, and fewer economically disadvantaged students (See Appendix A).

Given natural variation in the reading and writing abilities of elementary school children, we used a mixed approach to data collection. We interviewed the youngest children in our study, first and second graders, usually in pairs. Because being interviewed is an atypical experience, pairing is recommended for young children, especially when the adult interviewer is not known by the children (Mayall Reference Mayall, Christensen and James2000). In the interview setting, the researcher sat with the children at a desk or table, read each item aloud verbatim from the script, and wrote out their responses on a printed script. In contrast, students in grades 4–6 completed an individual survey using crayons (for the first task), pencil, and paper as a researcher read the questions aloud to a group. We surveyed a majority of the third graders in our study and interviewed the others. Our preference was to interview children in this grade, yet some school administrators requested that we survey them given that the interviews required more time.

Each student participant first completed the Draw a Political Leader (DAPL) task (described further below). All participants also answered a set of questions regarding exposure to political materials and another related to political interest, items that appeared near the end of the questionnaire. In addition, the middle of each child’s questionnaire contained one of three possible modules. We present results from one of those modules—a replication of items from Greenstein’s (Reference Greenstein1965) childhood socialization study—alongside results gathered from all participants. We randomly assigned school classrooms to a module; each module contains responses from approximately one third of the respondents. We focus on three types of attitudes from the questionnaires: perceptions of political leaders, exposure to political activities, and political ambition and interest in gendered occupations (survey items for all measures included in our analyses are in Appendix B).

Perceptions of Political Leaders: To begin the drawing task, we provided children in our study with a bag of crayons (including eight classic Crayola colors and eight multicultural crayons including skin tone colors such as tan, apricot, and burnt sienna) and white paper with a blank box. The researcher first read the following prompt:

Close your eyes and imagine a political leader at work. A political leader is a person who wins an election and then has the job of helping people and solving problems in the community and the country. In the space below, draw what you imagined. Some examples of political leaders are people like: the mayor, the governor, people who work in Congress.

For consistency, interviewers did not provide further prompts or information beyond the introductory statement. We then gave students time to complete their drawings. After drawing their picture, we asked students three open-ended follow-up questions about what the leader was doing in the drawing, how they would describe their leader, and what the leader does on a typical day.

Trained research assistants coded each drawing and the responses for several variables of interest. Coders used names of known political leaders, features of the image such as what the leader is wearing (e.g., a skirt), or pronouns in the written responses to identify the sex of the political leader. Answers to the second open-ended response, “list three words that come to mind when you think of this political leader” were used to identify feminine and masculine traits associated with the leader. Here, coders identified whether any of the following masculine traits were mentioned explicitly: achiever, brave, cool, conqueror, courageous, determined, hero or heroine, important, leader, in charge, powerful, ruler, or strong. They similarly noted whether the following feminine traits were written: caring, compassionate, helpful, kind, friendly, nice, loving, or trustworthy. Coders also identified whether the leader drawn was a known contemporary political leader or historical figure and identified political activities in the images (e.g., voting). For more on the DAPL task, the coding scheme, sample DAPL drawings that demonstrate the coding scheme, and intercoder reliability, see Appendix C. We use the DAPL to understand both political socialization (whether children draw a known political leader and whether they depict political activities) and gendered political socialization (the sex and gendered characteristics of the political leader drawn).

Exposure to Political Activities: We adapted two questions from a common evaluation used to gauge student interest in science, the Test of Science Related Attitudes (TOSRA; Fraser Reference Fraser1978), to measure exposure to politics. Specifically, students report how often (from Never [1] to Often [4]) they had engaged in the following activities during the prior year: “Read books and magazines about government, politics or history” and “Watch programs on TV about history, politics, government or things going on in the world.” These two items, asked of all students, are combined into a single scale, where higher values indicate more frequent exposure to politics. We use these measures to understand political socialization.

Political Interest: To assess political interest, we adapted items from the Noyce Enthusiasm for Science scale (Fraser Reference Fraser1978). These questions gauge children’s excitement and curiosity regarding politics and government, such as whether they are excited to learn about politics or curious about political careers. Interest in political activities is an index of agree/disagree responses to the following sentiments: (1) politics, government, and history are exciting topics; (2) curiosity to learn about politics, government, and history; (3) desire to have a political job; and (4) learning about government is boring [reverse coded]. We use these measures to understand gendered political socialization.

Political Ambition and Interest in Gendered Occupations: Our measure of political ambition is an adaption of an item used in Greenstein’s (Reference Greenstein1965) classic study. Children who completed this module of our study (n = 455) identified “all the jobs you would like when you are older” out of a list of 10 options: police chief, religious leader, teacher, judge, principal, doctor, president, mayor, business owner, and governor of a state. To look for evidence of gender socialization, we examine interest in four nonpolitical jobs that reflect feminine (doctor, teacher)Footnote 5 and masculine traits (business owner and police chief). To look at gendered political socialization, we observe interest in political careers by counting the number of political careers that each student indicated (judge, president, mayor, and governor), divided by the total number of jobs that the child selected.

Results

We argue that three processes shape children’s political worldviews: gender socialization, political socialization, and gendered political socialization. In our data, we look for evidence of gender socialization based on whether sex differences emerge in levels of interest in nonpolitical but gendered professions. We assess political socialization by examining children’s ability to identify political leaders and activities and through their exposure to politics. To uncover evidence of gendered political socialization, we look to see whether children express gendered perceptions of political leaders and whether sex differences emerge in political interest and ambition. With these processes, we anticipate that age plays a critical role: as they develop, children learn new information and internalize societal expectations.

Learning about Gender

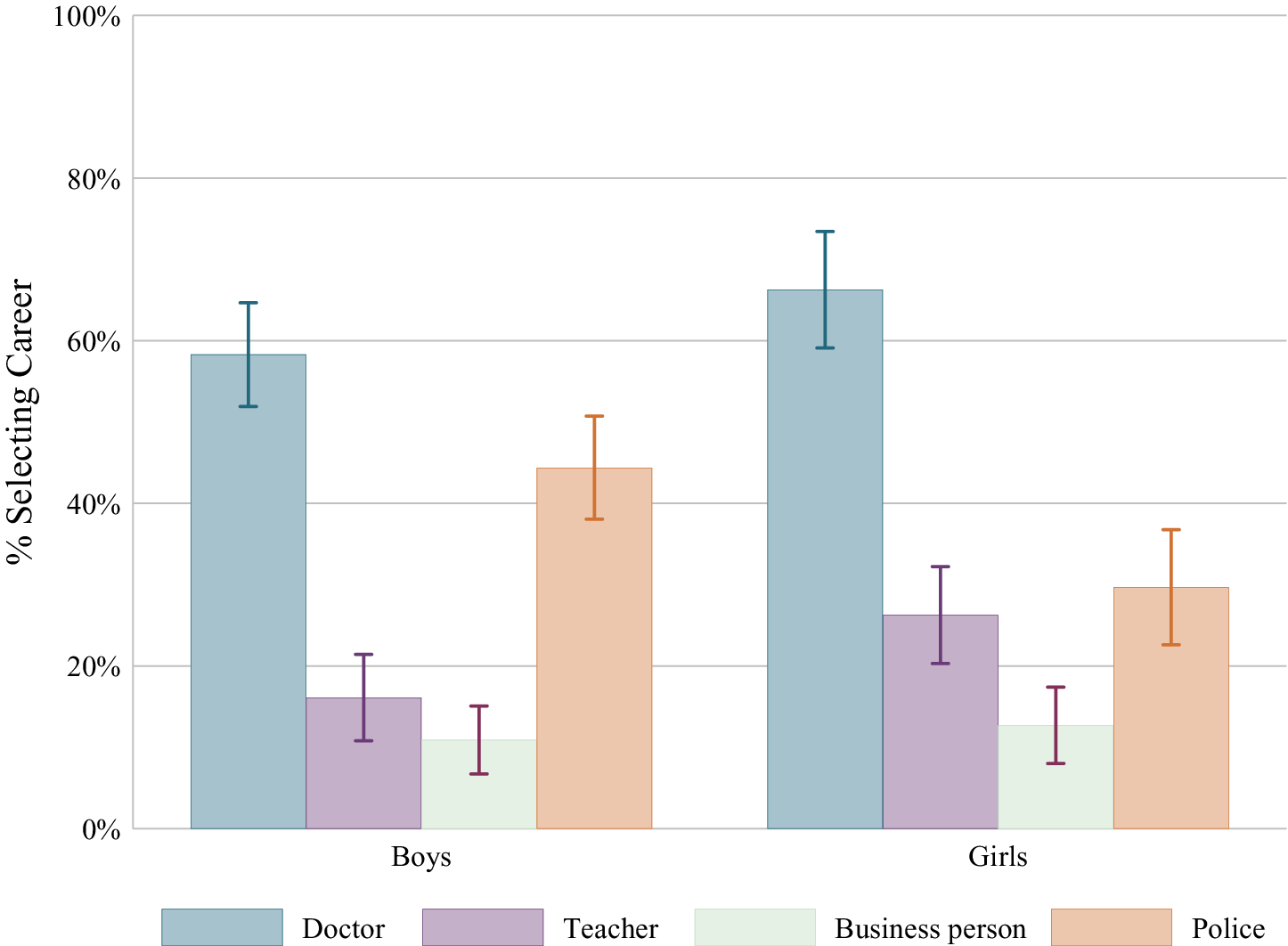

First, to find evidence of gender socialization we look at the mean level of interest in four professions, two of which are occupations that embody feminine traits (e.g., communal and caring), and two that embody masculine traits (e.g., agentic and strong) (Hypothesis 1). We estimate multilevel logistic regression models with the selection of each career as the dependent variable and controls for child sex, race, ethnicity, age, and knowledge and clustered errors at the classroom and location levels. Post hoc predicted probabilities for boys and girls are displayed in Figure 1 (full models in Appendix Table D1a; post hoc values in Appendix Table D1b). The values presented below are predicted probabilities and significance values from these multilevel models with clustered errors at the classroom and location level.

Figure 1. Gender Socialization: Careers Selected by Boys and Girls

Note: Predicted probabilities from a multilevel model with clustering at classroom and location level. Controls include student age, race, ethnicity, and knowledge. See Appendix Table D1a for full models.

We find some evidence to support our first hypothesis: girls express more interest in being a doctor

![]() $ \left(\hskip1.5pt girls\;\overline{X}=0.66; boys\;\overline{X}=0.57;p=0.08\right) $

or a teacher

$ \left(\hskip1.5pt girls\;\overline{X}=0.66; boys\;\overline{X}=0.57;p=0.08\right) $

or a teacher

![]() $ \left(\hskip1.5pt girls\;\overline{X}=0.26; boys\;\overline{X}=0.15;p=0.01\right) $

than do boys and less interest in being a police officer

$ \left(\hskip1.5pt girls\;\overline{X}=0.26; boys\;\overline{X}=0.15;p=0.01\right) $

than do boys and less interest in being a police officer

![]() $ \left(\hskip1.5pt girls\;\overline{X}=0.30; boys\;\overline{X}=0.44;p=0.004\right). $

There are no differences in overall interest in being a business leader

$ \left(\hskip1.5pt girls\;\overline{X}=0.30; boys\;\overline{X}=0.44;p=0.004\right). $

There are no differences in overall interest in being a business leader

![]() $ \left(\hskip1.5pt girls\;\overline{X}=0.12; boys\;\overline{X}=0.10;p=0.53\right) $

.

$ \left(\hskip1.5pt girls\;\overline{X}=0.12; boys\;\overline{X}=0.10;p=0.53\right) $

.

Hypothesis 2 predicts that gendered occupational choices should strengthen with age. As shown in Figure 2, girls do express increasing levels of interest in feminine professions that emphasize caring for others as they age (see Appendix Table D2). This is particularly true for interest in being a doctor. At age six, 52% of girls say they are interested in being a doctor. At age 12, 81% indicate interest in this career path. Across the same age span, the percentage of boys who are interested in being doctors increases only slightly, from 56% to 60%. At the lower age levels, the difference between boys’ and girls’ interest is insignificant. However, by ages 11 and 12, girls express significantly more interest in being a doctor (see Appendix Table D4). Interest in the feminine profession of teaching is also marked by an upward trajectory for girls, although boys demonstrate a similar rate of increase.

Figure 2. Gender Socialization: Interest in Feminine Professions by Sex and Age

Note: Predicted probabilities from a multilevel model with clustering at classroom and location level. Controls include student age, race, ethnicity, and knowledge. See Appendix Table D2 for full models.

As expected, we also find some evidence of a decrease in interest for girls in masculine professions, or those characterized by assertiveness and leadership (see Figure 3). At age six, 18% of girls report interest in being a business owner. At age 12 that interest drops to less than 8%. For boys, the pattern is reversed, with levels of interest increasing between ages six and 12 from 2% to 20%. At the younger ages, there are significant differences, with girls more likely to list a business owner. By age 11, these significant differences disappear, with boys and girls equally likely to list the career.

Figure 3. Gender Socialization: Interest in Masculine Professions by Sex and Age

Note: Predicted probabilities from a multilevel model with clustering at classroom and location level. Controls include student age, race, ethnicity, and knowledge. See Appendix Table D3 for full models.

Both girls and boys express a decreasing level of interest in serving as a police chief with age. At age six, 33% of girls express interest in serving as a police chief, and at age 12, 26% of girls are interested in this role. Among boys, 54% of six-year-olds indicate an interest in policing compared with 37% of 12-year-olds.Footnote 6 The differences are significant at younger ages, with boys expressing more interest. However, by age 11 and 12, the gender differences between boys and girls are insignificant (see Appendix Table D4).

Our data offer support for our Hypotheses 1 and 2. With age, girls in our study have increasing interest in feminine career paths alongside decreasing interest in masculine career paths. While the results are more mixed for boys, we interpret these results as strong evidence of the process of gender socialization among girls and the internalization of gendered expectations that is a part of that process.

Learning about Politics

Next, we explore whether children in our study demonstrate signs of learning about and engaging with politics. To do this we first examine whether children drew a known contemporary or historical political leader in the DAPL task and whether the image they drew contained at least one political activity (such as voting). Children who have successfully learned about the political sphere should be able to draw a political leader or depict a political activity. We run separate logistic regressions for each dependent variable, examining the influence of age while controlling for sex, race, ethnicity, and knowledge. We then plot the post hoc predicted values for each variable by age. Figure 4 shows strong evidence for political learning. Even at age six, one quarter of all children draw a known political leader in their DAPL task. At age 12, this increases to over 50%. Students complied with the DAPL instructions and drew a figure connected to politics, but this share increases with age, growing from 86% drawing at least one political activity at age six to almost 95% of children at age 12. These results demonstrate that most children can make a basic connection to a political activity and a political leader by first grade and that political learning increases with age.

Figure 4. Political Socialization: Known Political Leaders and Political Activities in DAPL Drawings by Age

Note: Predicted probabilities from a multilevel model with clustering at classroom and location level. Controls include student sex, race, ethnicity, and knowledge. Full results in Appendix Table D5.

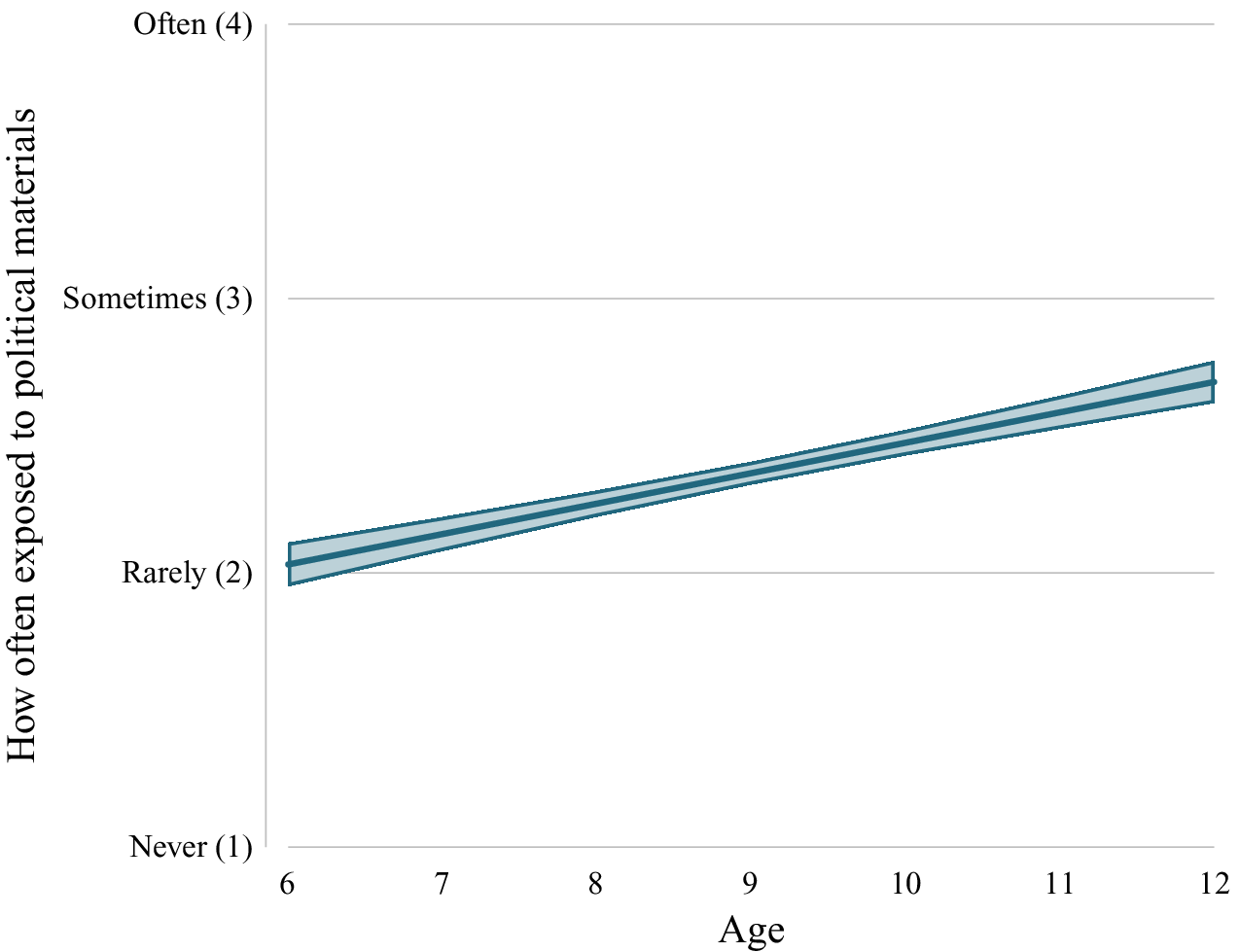

In addition, we expect that as students age, their levels of exposure to politics will increase. Using ordinary least squares with controls for sex, race, ethnicity, and knowledge, we examine the influence of age on political exposure and then model post hoc predicted values by age. As shown in Figure 5, at age six, children report, on average, that they “rarely” (or 2 on the 1–4 scale from Never [1] to Often [4]) are exposed to political materials (books, magazines, programs on TV), but this increases more than a half-point on the four-point scale by age 12 to an average exposure of 2.7. Thus, consistent with our expectations for Hypothesis 3, children demonstrate increased political understanding and interest with age, which is indicative of the political socialization process.

Figure 5. Political Socialization: Exposure to Political Materials by Age

Note: Predicted probabilities from a multilevel model with clustering at classroom and location level. Controls include student sex, race, ethnicity, and knowledge. Full results in Appendix Table D6.

Learning about Gender and Politics

Finally, we examine the evidence for gendered political socialization. We anticipate that the internalization of gender roles and norms among children and political learning during childhood will work to produce a shared sense among children that politics is a male domain and that divergent levels of political interest and ambition will emerge among boys and girls. To find evidence of this, we first look to the DAPL task to see whether men and masculine traits dominate these depictions of leaders. We next examine whether sex differences emerge in children’s own levels of political interest and political ambition.

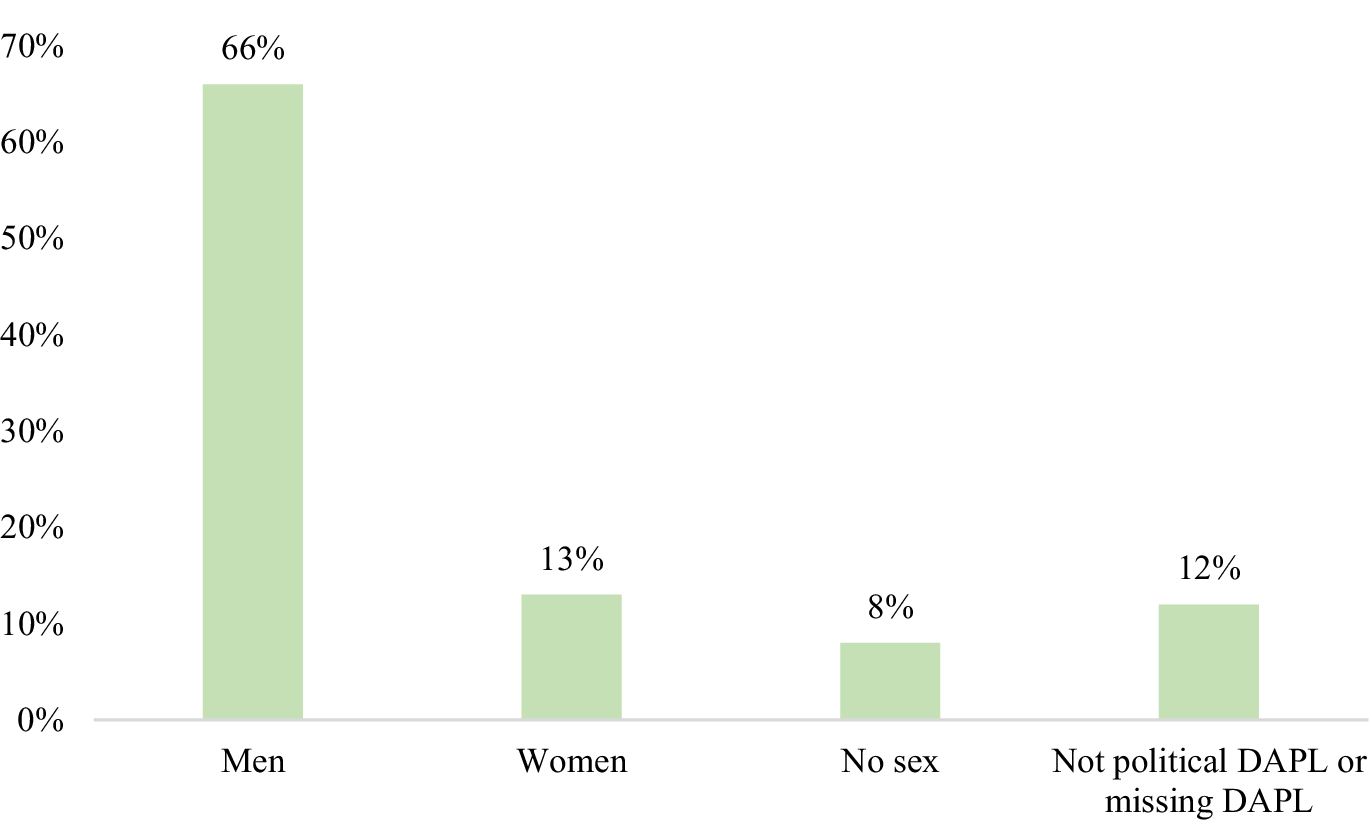

Politics as a Man’s World

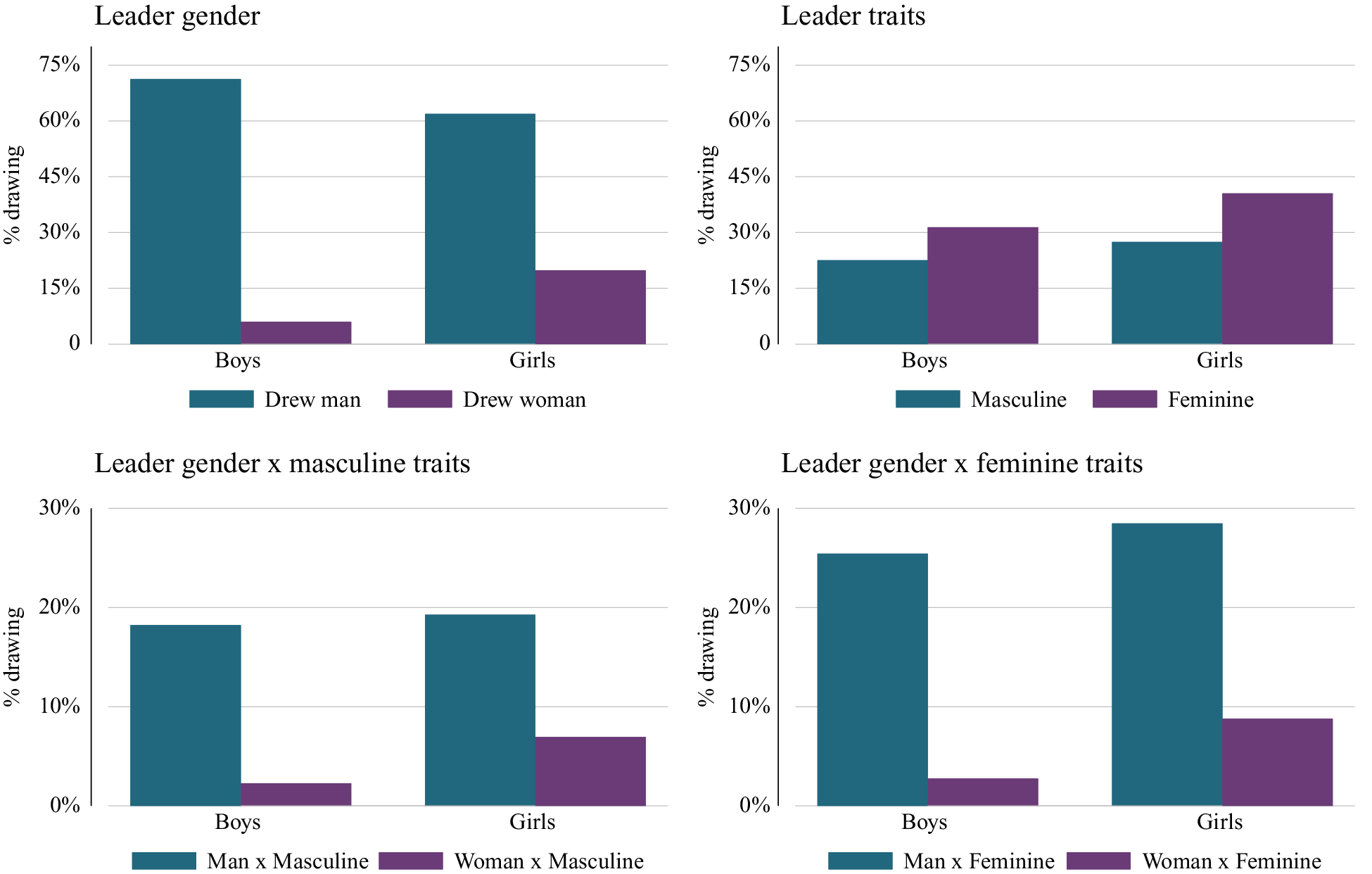

In examining children’s DAPL drawings, we find that they see politics as a “man’s world”—one that is dominated by male leaders. Consistent with our expectations in Hypothesis 4, we find that most children draw male political leaders in their DAPL task. Of the 1,604 students in our study, 66% (n = 1,059) drew a man as the primary political leader but only 13% (n = 214) depicted a woman (see Figure 6).Footnote 7 Of note, male political leaders dominated the drawings of students regardless of sex: 71% of boys drew male leaders and 61% of girls drew them. Also consistent with Hypothesis 4, we observe that girls (20%) in our sample were more likely to draw women leaders than boys (6%); these differences are statistically significant in both difference of means tests and in full multilevel models with controls (see Appendix Table D7).

Figure 6. Gendered Political Socialization: Sex of Political Leaders in DAPL Drawings

Note: See Appendix C for details on coding.

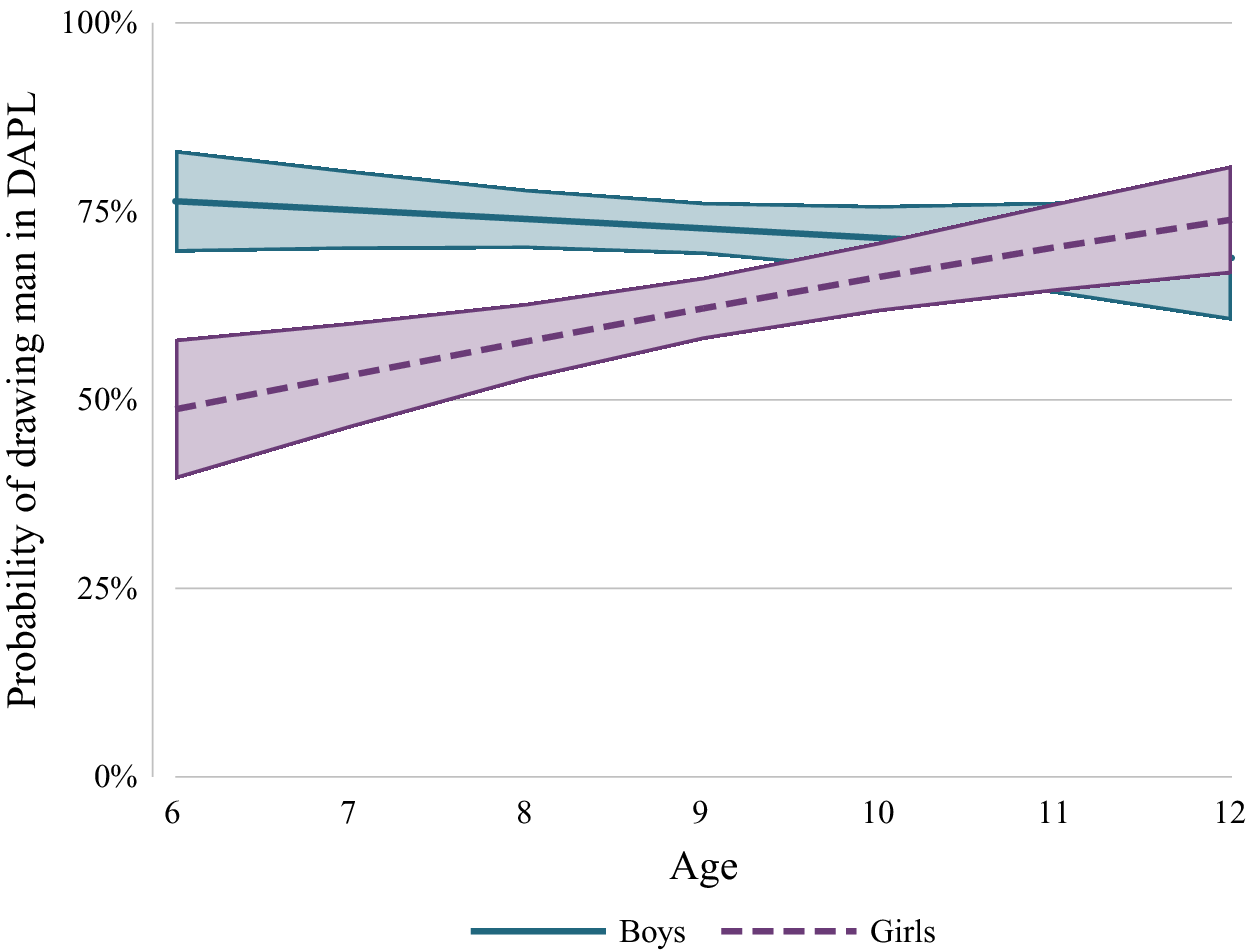

To test Hypothesis 5, we examine how age and sex function as predictors of drawing a man as a political leader in the DAPL task. We run a logistic regression controlling for race, ethnicity, and knowledge, and plot the post hoc predicted values for girls and boys by age for the likelihood that they drew a man in the DAPL task. Figure 7 shows that although there is no real difference among boys in the likelihood of drawing a male leader as they get older (moving from a 75% probability at age six to a 71% probability at age 12), girls increasingly draw men as political leaders. At age six, the probability of a girl drawing a man as a political leader is 47%; by age 12 that probability increases to almost 75%. These results suggest that sex differences in how children see political leaders diminish as they get older because of changes in girls’ perceptions of politics. Girls are more likely to draw men as political leaders as they age. Just as in the world of science, as children get older and are more aware of the reality that politics is dominated by men (for example, in 2017, 81% of congressional seats were held by men; Center for American Women and Politics 2017), their images of the political world become more male-centric. This constitutes strong evidence of gendered political socialization.

Figure 7. Gendered Political Socialization: Likelihood of Drawing a Man in the DAPL across Age by Boys and Girls

Note: Predicted probabilities from a multilevel model with clustering at classroom and location level. Controls include student age, race, ethnicity, and knowledge. Full results in Appendix Table D7.

Gender can be expressed in multiple ways; in addition to identifying whether a leader is male or female, we look at the gendered traits included with each drawing. By gendered trait, we refer to a child’s use of either positive or negative traits associated with stereotypes of men (e.g., brave, powerful, angry, uncaring) or women (compassionate, trustworthy, weak, not in charge) to describe the political leader they drew. Figure 8 provides the differences in means in the gender and gendered traits of DAPLs across boys and girls. In line with Hypothesis 5, that children will see politics as masculine, we anticipate masculine traits will be more prevalent than feminine traits. However, as shown in the top of Figure 8, while children draw far more male leaders than female leaders, masculine traits are not more prevalent than feminine traits. Indeed, children use feminine traits more often than masculine traits, with 31% of boys and 41% of girls invoking feminine traits in their drawings versus 23% of boys and 27% of girls drawing masculine traits. Indeed, the lower half of Figure 8 shows that most common type of depiction for all children was a male leader with feminine traits. While it is possible that children do perceive political leadership as characterized by feminine traits, we must note that our prompt for introducing the DAPL task to all participants is likely to have primed feminine traits such as “helping,” and this may help to explain the strong presence of feminine traits in these drawings.

Figure 8. Gendered Political Socialization: Sex and Traits of Political Leaders in DAPL Drawings by Boys and Girls

Note: See Appendix C for details on coding.

When we look at the combination of the leaders’ sex and gendered traits across ages, we see that older children were more likely to draw male leaders and depict masculine traits than younger children; this is true for both boys and girls (see Figure 9). We find that there is a decrease in the presence of male leaders with feminine traits as children get older, and there is little change across ages in terms of the prevalence of women leaders with masculine traits. Finally, although there is no difference across ages for boys, there is a decrease in the presence of women leaders with feminine traits drawn by girls. Overall, we see that as they age, girls are less likely to use feminine traits to describe a political leader and they are more likely to depict political leaders as men possessing masculine traits.

Figure 9. Gendered Political Socialization: Sex and Traits of Political Leaders in the DAPL Drawings by Sex and Age

Note: Predicted probabilities from a multilevel model with clustering at classroom and location level. Controls include student age, race, ethnicity, knowledge, and whether the drawing depicts any traits. Full results in Appendix Tables D8 and D9.

Sex Differences in Political Interest and Ambition

Our final indicators of gendered political socialization relate to our prediction in Hypothesis 6 that girls will report less interest in politics, in general and as a career choice, and that these relationships will intensify with age. We find support for each of these predictions, showing that girls express less interest in politics and less ambition than boys and that the gaps increase with age.

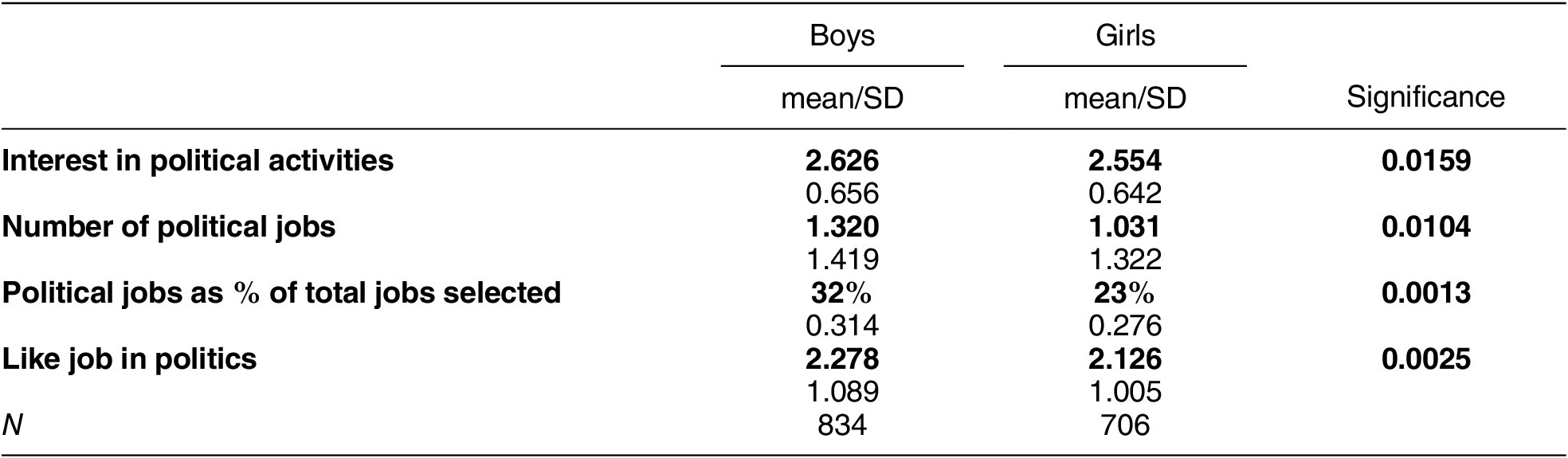

Table 1 shows that mean levels of interest in political activities (measured on a four-point scale) are lower for girls (2.55) than boys (2.63). Mean levels of interest in political careers are also lower for girls (1.03) than boys (1.32). As a percentage of all jobs, girls were interested in political jobs at a rate of 23% while boys were interested in political jobs at 32%. Finally, on average, girls reported that they would like a job in politics at a lower rate than did boys (2.13 for girls, 2.28 for boys). All these differences reached significance at conventional levels. Thus, girls in our sample are systematically less interested in politics and less politically ambitious than boys are.

Table 1. Gendered Political Socialization: Sex Differences in Mean Levels of Interest and Political Ambition

Note: Significance in test of difference between boys and girls using a difference of means test, unequal variance. Girls are also less interested and less likely to list political jobs with full controls; see Appendix Table D10.

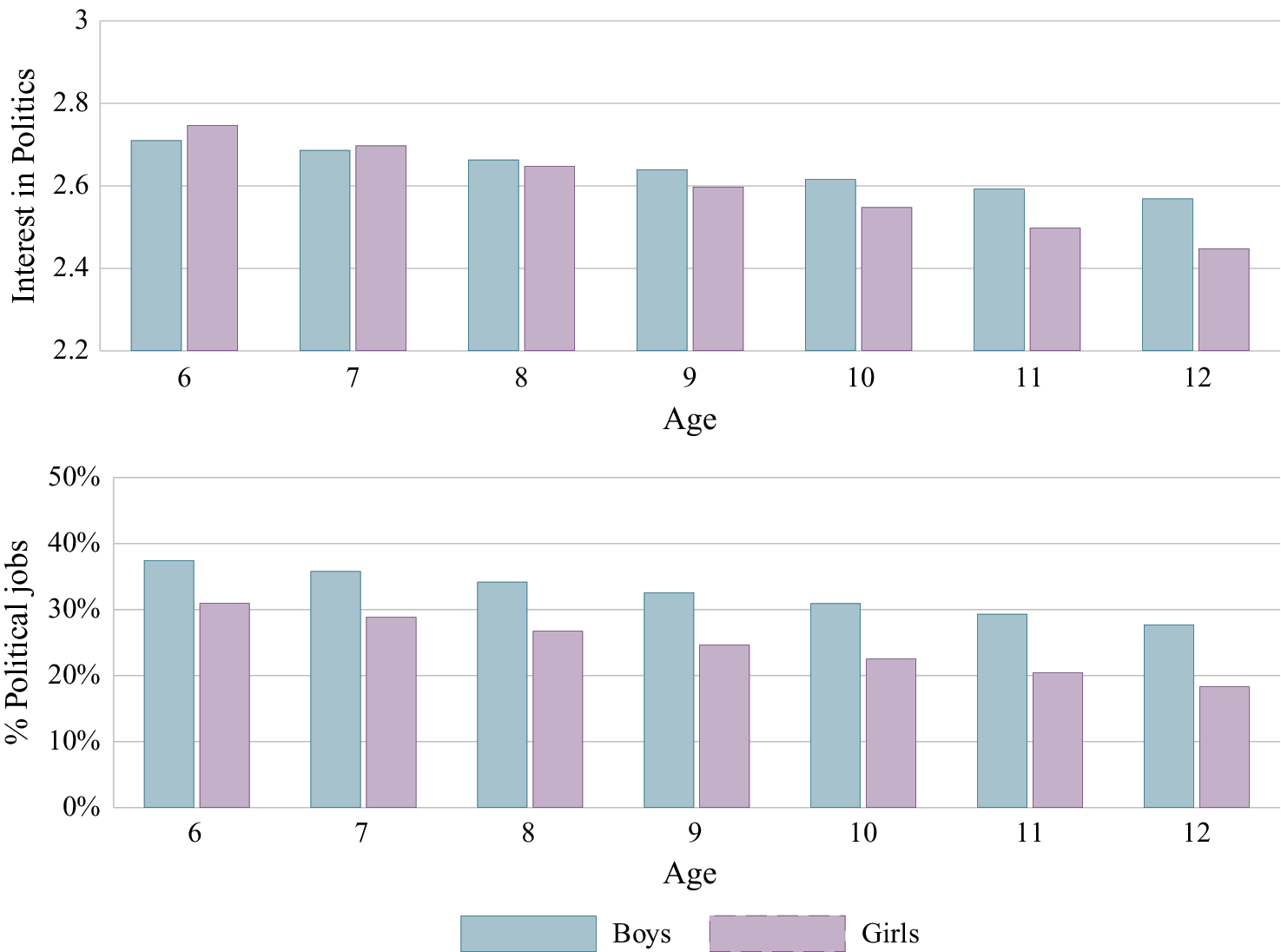

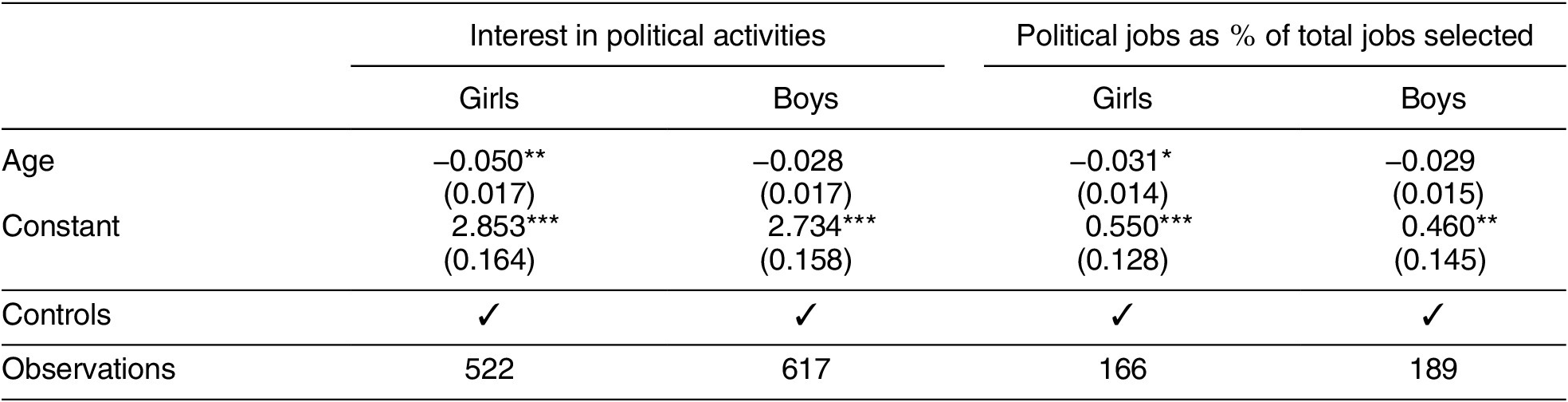

How do age and sex work together to predict levels of interest in politics and political careers? Figure 10 provides post hoc predicted values for political interest and the share of political jobs in separate models for boys and girls. While boys’ levels of interest in politics drop just slightly between ages 6 and 12, girls experience a clear decrease in interest as they age. At age six, girls report higher levels of interest in politics than do boys (2.8 vs. 2.7 on a four-point scale), but by age 12 their interest falls below that of boys (2.4 vs. 2.6). Turning to interest in political careers, the bottom panel of Figure 10 shows that girls express lower interest than do boys at most ages, but this difference widens as they grow older. Boys’ interest in political careers decreases only slightly across ages (from 36% to 29%), but girls experience a steady drop in interest from age 6 to age 12 (31% to 18%). Finally, in separate models by child sex (see Table 2), age is insignificant in the models for boys but significant and negative for girls for both measures. Together, these results suggest that all children turn away from politics as they get older (like trends among adults; see Shames Reference Shames2017) but that for girls this change is more dramatic.

Figure 10. Gendered Political Socialization: Levels of Political Interest and Political Ambition by Sex and Age

Note: Predicted probabilities from a multilevel model with clustering at classroom and location level. Controls include student age, race, ethnicity, and political knowledge. See Appendix Table D10 and D11 for complete models and full results.

Table 2. Gendered Political Socialization: Age, Interest, and Political Ambition for Boys and Girls

Note: Standard errors in parentheses. Multilevel model (classroom and location) with controls for race, ethnicity, and political knowledge. See Appendix Table D10 for full models. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

Discussion

We develop and test a theoretical framework where gender socialization and political socialization combine to create gendered political socialization, which powerfully conveys to children that politics is a male-dominated domain and produces consequential sex differences in levels of political interest and ambition among children. Clear evidence for each process supports the idea that sex-based political inequalities are rooted in childhood.

Our most troubling results emerge from our examination of gendered political socialization. We find that both boys and girls perceive politics as male dominated. Yet, it is among girls where we see the most dramatic effects of change across their childhood. As they get older, girls turn away from politics, and we observe this in two different ways. First, with age, girls are more likely to draw men as political leaders and less likely to describe political leaders as possessing feminine traits. On these dimensions, differences between girls and boys reduce with age. This suggests that with increased knowledge about politics, girls are less likely to identify members of their own sex as political leaders and are more likely to describe leaders whose gendered traits are a mismatch to those they are socialized to possess. Second, girls are also less interested in politics and political careers than boys are, and this gap grows wider as children age. While at age six, girls are more interested in politics than boys are, their interest levels drop as they age. In comparison, the decrease in boys’ interest is substantively smaller and statistically insignificant.

As they internalize gender roles and gendered traits with age, girls are pulled toward “feminine” roles and move away from politics. Gendered political socialization shapes both the perceptions that girls have of the political world and their own preferences. Why might this happen? Consider the political world that children today observe. In the United States women compose, on average, 29% of elected leaders across state and national offices (Center for American Women and Politics 2021), and the highest-profile political figure, the US President, has never been a woman. Additionally, children observe a political landscape that is marked by intense conflict and gridlock (Binder Reference Binder2003), partisan hostility (Miller and Conover Reference Miller and Conover2015), and even dehumanization of opponents (Cassese Reference Cassese2021). This environment is distasteful to Americans of all genders and depresses interest in running for office (Shames Reference Shames2017), but this context may make politics particularly unappealing for women and girls who are socialized to embody traits counter to this context. Thus, despite journalistic discourse that celebrates the collaborative style of women office holders (Lawrence Reference Lawrence2013) and praises their trailblazing paths (Parti Reference Parti2021), the increasingly conflictual and hypermasculine state of American politics may exacerbate the sex differences we demonstrate in this article.

There are, of course, limitations to our study and therefore our ability to draw broad conclusions. Our purposive sample is not representative of the general population of children ages 6–12 in the US. Yet, the diverse and geographically varied sample does offer findings that are strongly suggestive of what may be happening among children these ages. Nonetheless, larger samples of nonwhite children must be conducted to understand how the intersection of race, ethnicity, and sex shape the gendered political socialization of children. We also acknowledge that the perceptions of masculine and feminine traits as more and less compatible with politics, respectively, may vary by racial and ethnic group. Collectivist philosophies that have been (and are) central to the political work of minoritized communities (Dawson Reference Dawson1994; Reference Dawson2003) and the writings of Black feminist scholars (for example, hooks Reference hooks1984) emphasize feminine traits and goals in political work. Thus, we may be overestimating the value of masculine traits and goals in politics, particularly among children of color.Footnote 8 Components of racial differences are evident in our research; for example, children in our southern location (who represent a majority of the Black respondents in our sample) were less likely to draw men in the DAPL task.Footnote 9

Scholars have long debated the importance of childhood political socialization (Greenstein Reference Greenstein1965; Sapiro Reference Sapiro2004). But we join other scholars in advocating for a revival of childhood socialization research (Bigler et al. Reference Bigler, Arthur, Hughes and Patterson2008; Patterson et al. Reference Patterson, Bigler, Pahlke, Brown, Hayes, Ramirez and Nelson2019; van Deth, Abendschön, and Vollmar Reference van Deth, Abendschön and Vollmar2011). These studies are essential for fully understanding the ways in which children learn about the political world. As we learned in this work, studying children is time intensive and there are numerous other barriers such as gaining human-subjects approval and creating partnerships for access with school district and building leaders. However, given dramatic political events in recent years, it is important to empirically test the adage that “our children are watching” and the effects of what they are seeing on their political attitudes and behavior. Investing in systematic studies of US children, we believe, will continue to show that children are interesting political actors in their own right.

Conclusion

As records are broken regarding women’s electoral representation and as women such as Vice President Kamala Harris and Speaker of the House Nancy Pelosi take their places at the highest levels of political power in the United States, it is important to understand that sex-linked inequalities still exist when it comes to interest in politics and political ambition. These differences emerge in childhood and grow more acute at older ages when boys and girls develop more complex and sophisticated understandings of politics. Multiple forces shape how girls envision themselves and their place in the political world. Schools, the media, families, peers, and other socializing agents inadvertently highlight the mismatch between feminine traits and feminine roles and the male-dominated domain of politics. As girls learn more about politics and internalize society’s expectations of them, they are less likely to see traditional politics as a place for them to lead. And while our data only suggest, but do not offer direct evidence of, continuity between attitudes in childhood and attitudes in adulthood, they do indicate that efforts to elevate the political interest and ambition of women must begin early.

What can be done to bolster girls’ political interest and ambition? Certainly, more women in politics could serve to engage girls in politics. Scholars have found that role models can bolster girls’ interest in male-dominated fields (Beaman et al. Reference Beaman, Duflo, Pande and Topalova2012; O’Brien et al. Reference O’Brien, Hitti, Shaffer, Van Camp, Henry and Gilbert2017). The tendency for children to draw male scientists has decreased over time as more women have entered the sciences (Hill, Corbett, and St. Rose Reference Hill, Corbett and Rose2010; National Science Foundation 2017) and as popular media (Rawson and McCool Reference Rawson and McCool2014) and textbooks have reflected that increase (Pienta and Smith Reference Pienta, Smith, Hickman and Porfilio2012). Some evidence within politics also demonstrates role model effects (Campbell and Wolbrecht Reference Campbell and Wolbrecht2006; Stauffer Reference Stauffer2021; Wolbrecht and Campbell Reference Wolbrecht and Campbell2007). With an increase in the number of women who have taken on political leadership roles (elected and nonelected), including highly visible leadership roles, future children may be more likely to associate women with political leadership. Moreover, the visibility of figures like Alexandra Ocasio-Cortez, Stacey Abrams, Elizabeth Warren, and Greta Thunberg may expand children’s notions of the characteristics and professional paths that have long been associated with political leaders.Footnote 10 Yet, merely increasing the number of women in high profile political roles is unlikely to be sufficient. At the time of our data collection, Hillary Clinton was a highly visible national political figure, yet only 15 children depicted her in their drawings. This reflects the documented limitations of the role model effect (Campbell and Wolbrecht Reference Campbell and Wolbrecht2020; Wolbrecht and Campbell Reference Wolbrecht and Campbell2017). And, as we argued, gendered political socialization is complex and its constituent processes are slow to change.

A wide range of interventions, like those in STEM fields, are needed in social science education. One cause of gender inequality in STEM fields is the perceived incongruence between the communal goals valued by women and girls and the agentic goal fulfillment associated with STEM professions (Diekman, Weisgram, and Belanger Reference Diekman, Weisgram and Belanger2015). Given this, to increase girls’ interest in STEM, interventions must convey communal goals can be achieved within the field of interest (Diekman, Weisgram, and Belanger Reference Diekman, Weisgram and Belanger2015; see also Chun and Harris Reference Chun and Harris2011). We argue that the same must be done within social science education and political discussions. Framing political leadership and politics as spaces that value communal goals could bolster girls’ interest in politics and political careers, as has been found in adult samples (Schneider et al. Reference Schneider, Holman, Diekman and McAndrew2016). Environments characterized by consensus, as opposed to conflict, are more likely to promote political knowledge among girls than among boys (Lay Reference Lay2017; Wolak and McDevitt Reference Wolak and McDevitt2011). Relatedly, school curricula can incorporate more examples of women leaders in politics who exhibit an array of gendered traits and move away from textbooks and classroom materials that present political leaders as predominantly male and masculine (Cassese, Bos, and Schneider Reference Cassese, Bos and Schneider2014; Lay et al. Reference Lay, Holman, Bos, Greenlee, Oxley and Buffett2021). Classroom exercises can also encourage students to reflect on their own potential as political leaders (Greenlee, Holman, and VanSickle-Ward Reference Greenlee, Holman and VanSickle-Ward2014), helping students recognize that communal traits and goals are compatible with leadership roles. Along with these interventions, as children have more examples of women leaders—some of whom may make pathways to politics that embody feminine traits or goals more salient—their associations between masculinity and politics may loosen.

We acknowledge that in addition to interventions, broader trends connected to gender equality may slowly shift the context in which children learn about gender. The foundation of social role theory is that children mimic the gendered division of labor that they observe in the home and that this behavior reinforces (and perpetuates) gender roles, traits, and motivations. As the close adherence to gender roles is shaken up due to factors such as men’s greater participation in domestic work (Altintas and Sullivan Reference Altintas and Sullivan2016) and women’s greater participation in the paid workforce (Catalyst 2020; US Department of Labor 2020), we may see slow-moving changes in children’s gender socialization.Footnote 11 Thus, changes in the social and political world will have important implications for the development of young minds, and together, they will alter the process of gendered political socialization.

Supplementary Materials

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit http://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055421001027.

Data Availability Statement

Research documentation and data that support the findings of this study are available at the Amercian Political Science Review Dataverse: https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/YABNFF.

Acknowledgments

This research was previously presented at the 2019 Southern Political Science Association meeting, the 2019 International Society for Political Psychology meeting, and the 2019 European Conference on Politics & Gender. For research assistance, we thank Dzifa Adjei, Gianluca Avanzato, Kennedey Bell, Olivia Britton, Allison Buffett, Marcy Campbell, Larissa Cargal, Joanne Carminucci, Rachel Clarey, Alyssa Clune, Chloe Cook, Barb Friedhoff, Jordan Griffith, Phyllis Hinerman, Desi LaPoole, Joseph Maher, Daniella Michanie, Jason Nelson, Taina Orellana, Matthew Schattner, Fiona Schieve, Julianna Scionti, Emily Stoehr, Connie Storck, Alysa Tarrant, Linda Wang, and Julie Zalar. Dale Miller provided valuable assistance preparing the data files. We are especially grateful for all the students who answered our surveys and the principals, teachers, and parents who allowed us to work with the children.

Funding Statement

Funding for this research was provided by the Union College Faculty Research Fund, the Newcomb Institute at Tulane University, the Greenberg Fund and the Norman Fund at Brandeis University, and the College of Wooster’s Henry Luce III Fund for Distinguished Scholarship.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no ethical issues or conflicts of interest in this research.

Ethical Standards

The authors affirm that this article adheres to the APSA’s Principles and Guidance on Human Subject Research. The study received human-subjects Approval from the Institutional Review Boards at the authors’ institutions. Please see Appendix E for details on the ethics of the data gathering process.

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.