Introduction

The young animals are born with immature immune and digestive systems, which makes them highly susceptible to oxidative stress (Shah et al. Reference Shah, Cai and Zou2019). The incidence of oxidative stress often leads to decreased growth performance, feed efficiency, and survival rates in livestock (Du et al. Reference Du, Wang and Hu2023a, Reference Du, Wang and Xu2023b). A healthy and balanced microbiome is particularly important for the growth, development, and metabolism of ruminants. Specifically, there has been increasing interest in the early development of the gut or rumen microbiome in farm livestock as a means of maintaining health (Balasubramanian and Liu Reference Balasubramanian and Liu2024; Wang and Guan Reference Wang and Guan2022). However, feeding microorganisms alone presents challenges, such as low colonization rates or weak efficiency (Ban and Guan Reference Ban and Guan2021; Yadav et al. Reference Yadav, Kumar and Parsana2024). Therefore, it is essential to develop feeding additives that can improve the health of young animals, maximizing their overall growth performance.

Marine-derived bioactive compounds and probiotics provide a wide range of health benefits, including antioxidant, immunomodulatory, and anti-inflammatory effects (Babbar et al. Reference Babbar, Kaur and Null2024; Shahidi and Ambigaipalan Reference Shahidi and Ambigaipalan2015; Šimat et al. Reference Šimat, Elabed and Kulawik2020). These compounds have significant potential for applications in health supplements. Bacillus amyloliquefaciens-9 (BA-9), which is isolated from the intestinal tract of the white-spotted bamboo shark (Chiloscyllium plagiosum), can secrete potential antibacterial materials, such as β-1,3-1,4-glucanase and antimicrobial peptides (Zhang et al. Reference Zhang, Wei and Xu2020). Animal feeding experiments have demonstrated that this probiotic reduces the occurrence of diarrhea in goat kids and decreases oxidative stress in the mammary gland by altering the diversity of the intestinal microbial community (Li et al. Reference Li, Jiang and Zhang2021; Zhang et al. Reference Zhang, Xin and Jiang2021). Combining probiotics with Chinese herbal polysaccharides has been found to improve the growth performance of lambs and the diversity of rumen bacteria (Chen et al. Reference Chen, Guo and Yang2021). Recent data combining probiotics with traditional Chinese medicine suggests that this combination has an enhanced effect in inhibiting intestinal inflammatory responses and reducing disease recurrence compared to using probiotics or traditional Chinese medicine alone (Hu et al. Reference Hu, Ye and She2022). Combined with plant-derived bioactive compounds provides an ideal strategy to expand the usage of BA-9 in animal feeding.

Lonicera japonica Thunb (LT) is a widely used traditional Chinese herb with medicinal value attributed to the entire plant. This plant is rich in primary bioactive components including chlorogenic acid and luteolin glucoside. These components have antioxidant and immunomodulatory properties (Guo et al. Reference Guo, Lin and Wang2015; Shang et al. Reference Shang, Pan and Li2011; Zheng et al. Reference Zheng, Liu and Hou2022). Supplementation of LT extract significantly decreases the respiratory rate in heat-stressed dairy cows and promotes their antioxidant and immune functions (Ma et al. Reference Ma, Shan and Jin2020). However, the use of LT extract is challenged by the high costs of extraction, which can increase production expenses in large-scale applications (Cannavacciuolo et al. Reference Cannavacciuolo, Pagliari and Celano2024). Studies suggest that the vine of Lonicera japonica Thunb (VLT) also exhibits biological activity and can serve as a cost-effective alternative (Cai et al. Reference Cai, Wang and Zou2019).

BA-9 and LT have demonstrated significant antioxidant and health-promoting effects when used individually (Liu et al. Reference Liu, Bai and Wang2023, Reference Liu, Li and Xu2022; Xiong et al. Reference Xiong, Guo and Wang2021). However, the mechanisms underlying their combined effects remain unclear. BA-9, as a probiotic, may synergize with the bioactive compounds in VLT, such as flavonoids and phenolic acids, to enhance antioxidant capacity, modulate gut microbiota, and reduce oxidative stress more effectively than when used alone (Liu et al. Reference Liu, Bai and Wang2023, Reference Liu, Li and Xu2022; Xiong et al. Reference Xiong, Guo and Wang2021).

This study aims to investigate the dietary addition of VLT and the BA-9 and their interaction on the growth performance and health status of young ruminants using the Nanjiang Yellow Goats as a model.

Materials and methods

Material preparation

Bacillus amyloliquefaciens-9 (China General Microbiological Culture Collection Center number: 13337, accession number: CP021011) was isolated from the intestinal tract of the white spotted bamboo shark (C. plagiosum) (Wu et al. Reference Wu, Xu and Jin2018). The fermentation of Bacillus-9 was prepared following the reported procedure (Kritas et al. Reference Kritas, Govaris and Christodoulopoulos2006). The Bacillus-9 powder was prepared using a spray dryer (L-217, 1.0 mm nozzle, Lai Heng, Beijing, China). The inlet air temperature, aspirator, liquid flow, and compressed spray airflow were set at 55℃, 2 L/h, and 50 L/h, respectively. Corn starch was used as an adhesion agent at a ratio of 100 g/L. The colony-forming units in the powder were more than 2 × 109 /g. The production of BA-9 is gifted from Professor Zhengbing Lv in Zhejiang Sci-tech University.

The dry VLT (produced in Nanjiang County, Sichuan province, China) is ground using a grinder to obtain fine VLT powder. The powder was then sifted through a mesh sieve to remove larger particles, ensuring uniform and fine consistency. The prepared VLT powder was stored in dry, sealed containers.

Animal management and experimental design

This study was approved by the Experimental Animal Management Committee of Zhejiang University. A total of 32 healthy suckling goat kids (30 ± 3 days old) with similar body weights (8.68 ± 0.69 kg) were selected from the Nanjiang Yellow Goat Breeding Farm in Nanjiang County, Sichuan Province, China. Prior to the experiment, the health status of all goat kids was confirmed by veterinary examination. All goat kids were sourced from the same farm to minimize genetic and environmental variation and were uniformly managed during the preexperimental and experimental periods. Weights were recorded before morning feeding.

During the trial, all goat kids remained in the suckling phase and were not weaned. Natural nursing by their dams was maintained throughout the study, allowing each goat kid to consume milk freely according to its needs without any artificial restrictions. To support growth and gastrointestinal development, a gradually increasing amount of starter feed (pelleted) was introduced. Starter feed was provided twice daily at 8:00 AM and 3:00 PM. The specific feeding regimen was as follows: 100 g/day per kid during weeks 1–3, increased to 300 g/day per kid during weeks 4–5, and further increased to 500 g/day per kid during weeks 6–8. Pellets were evenly distributed at each feeding, and leftover feed was recorded after each meal to monitor feed intake and assess feeding behavior. Efforts were made to ensure adequate feed intake while minimizing wastage.

Using a randomized block design, the goat kids were randomly assigned to one of four groups (n = 8 per group). The groups were as follows: the control group (CON) fed only the basal diet (pellets, provided by Advanced Feed Co., Ltd., Chengdu, China); the BA-9 group, fed the basal diet supplemented with 0.3% BA-9; the VLT group, fed the basal diet supplemented with 2% VLT; and the MIX group, fed the basal diet supplemented with both 0.3% BA-9 and 2% VLT. To ensure consistency in nutrient intake, the feed for each group was thoroughly mixed with the respective supplements and processed into pellets. Water was provided ad libitum, and neck collars were used during feeding to reduce competition for feed.

The nutrient composition of the basal diet is presented in Supplementary Table S1. The experiment consisted of a 1-week adaptation period followed by a 7-week formal feeding period. Initial body weights (IBWs) were recorded at the start of the trial, and subsequent body weight measurements were conducted every 2 weeks in the morning before feeding to ensure accuracy and consistency.

Health monitoring was conducted daily throughout the study. Any signs of illness, such as diarrhea, lethargy, or reduced feed intake, were promptly recorded and treated as necessary. No major health issues were observed during the trial. These management practices ensured consistent experimental conditions and reliable outcomes.

Sample collection and analysis

Blood samples were collected from all kids on the last day. Blood was collected from the posterior jugular vein of each kid from 9:00 AM to 10:00 PM. The plasma was separated by centrifugation. The plasma levels of malondialdehyde (MDA), Glutathione peroxidase (GSH-Px), total antioxidant capacity (T-AOC), immunoglobulin A (IgA), immunoglobulin G (IgG), immunoglobulin M (IgM), interleukin-2 (IL-2), interleukin-4 (IL-4), and interleukin-6 (IL-6) were measured using specific commercial kits (Nanjing Jiancheng Biotech, Nanjing, Jiangsu, China) (Kritas et al. Reference Kritas, Govaris and Christodoulopoulos2006). Fecal samples were collected at last 2 days at the end of the experiment. The homogenized samples were snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80℃ for subsequent DNA analysis.

16S rRNA gene sequencing

Total genomic DNA was extracted from the fecal samples using a commercial kit (Tiangen Biotech, Beijing, China). The V3–V4 regions of the bacterial 16S rRNA genes were amplified and then paired-end sequenced (2 × 300 bp) on the Illumina MiSeq platform following standard protocols (Novogene Technology Co., Ltd., Tianjin, China).

Sequencing data analysis

Raw reads from different samples were demultiplexed and quality-filtered according to established methods (Zhong et al. Reference Zhong, Xue and Sun2020). Bioinformatics analysis was performed using QIIME 2. Shannon and Chao1 indices were calculated to estimate bacterial richness and community diversity (Bolyen et al. Reference Bolyen, Rideout and Dillon2019). Principal coordinate analysis (PCoA) and linear discriminant analysis effect size (LEfSe) were conducted using the Novomagic platform (https://magic.novogene.com). Correlation heatmaps were generated using the pheatmap package in R studio. Weighted gene co-expression network analysis (WGCNA) was performed using the WGCNA package in R studio, and the resulting network was visualized using Cytoscape (Version 3.8.0).

Statistical analysis

The data of growth performance was analyzed using a one-way ANOVA (Analysis of Variance) with the SPSS (Statistical Product and Service Solutions) software (SPSS v.19, SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). The statistical analyses of various factors in plasma and microbial diversity were performed by a one-way ANOVA. Data are presented as means plus SEM (Standard Error of the Mean). P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Correlation networks were generated using Spearman’s rank correlation coefficients and visualized using the Cytoscape. The significant correlation between bacterial genus and the immune globulins and cytokines was considered when |R| > 0.2 and P < 0.05).

Result

Supplementation of VLT and BA-9 significantly promotes the daily weight gain of goat kids

To investigate the effects of VLT and BA-9 on the growth performance of kids, we first assessed their impact on weight gain. As shown in Table 1, the IBW of the kids did not differ significantly among the four groups, but there was a trend toward differences in final body weight (FBW) (P = 0.094). Compared with the CON group, feeding goat kids with VLT alone significantly increased their ADG (P < 0.001) and TWG (P < 0.001). No significant changes were observed in the BA-9 group. Interestingly, the combined VLT powder and BA-9 (MIX group) outperformed the individual additions (P < 0.001). Compared to the CON group, feeding BA-9 alone did not significantly increase TWG or ADG. However, goat kids in the VLT group showed a significant increase in ADG (P = 0.007), which was further enhanced in the MIX group. Additionally, goat kids in the MIX group had higher average daily weight gain compared to both the CON group (P < 0.001) and BA-9 group (P = 0.014). Furthermore, there was an increasing trend in ADG compared to the VLT group (P = 0.081).

Table 1. Effects of BA-9 and VLT on the growth performance of Nanjiang Yellow Goat kids

Notes: All data are expressed as mean #x00A0;± SEM, (n = 8 per group).

1 IBW, initial body weight (weight of a 7-day-old lamb); FBW, final body weight (weight of a 50-day-old lamb); TWG, total weight gain (the difference between FBW and IBW); ADG, average daily gain.

2 CON, control group; BA-9, BA-9 probiotic supplementation group; VLT, VLT powder supplementation group; MIX, combined supplementation group of both VLT powder and BA-9 probiotic.

a,b,c Means without a common superscript differ significantly between the two groups at the same time point (P < 0.05).

VLT and BA-9 alter biomarkers in oxidative status and nutrition metabolism

To further investigate the physiological and metabolic mechanisms responsible for the increased daily weight gain in goat kids with the supplementation of VLT, BA-9, or their combination, we examined biomarkers associated with oxidative status and nutrition metabolism. As shown in Table 2, MDA (P = 0.504) and GSH-Px (P = 0.353) activities did not differ significantly among the different treatment groups. However, the combined supplementation significantly increased the T-AOC of the kids (P = 0.039). The single supplementation of VLT (P = 0.083) or BA-9 (P = 0.084) had minor effects on T-AOC. The MIX group exhibited a significantly higher T-AOC to the CON group (P = 0.021), the BA-9 group (P = 0.022), and the VLT group (P = 0.012). There were no significant changes in triglyceride (P = 0.387) and glucose (P = 0.661) among the different treatment groups.

Table 2. Effects of BA-9 and VLT on indicators of oxidative status and biochemical indices in Nanjiang Yellow Goat kids

Notes: All data are expressed as mean ± SEM, (n = 8 per group).

1 GSH-Px, glutathione peroxidase; MDA, malondialdehyde; T-AOC, total antioxidant capacity.

2TG, triglyceride; GLU, glucose; TP, totol protein.

3 CON, control group; BA-9, BA-9 probiotic supplementation group; VLT, VLT powder supplementation group; MIX, combined supplementation group of both VLT powder and BA-9 probiotic.

a,b Means without a common superscript differ significantly between the two groups at the same time point (P < 0.05).

Table 3. Effects of BA-9 and VLT on immune indices of Nanjiang Yellow Goat kids

Notes: All data are expressed as mean ± SEM, (n = 8 per group).

1 ALB, Albumin; IgA, immunoglobulin A; IgG, immunoglobulin G; IgM, immunoglobulin M

2 CON, control group; BA-9, BA-9 probiotic supplementation group; VLT, VLT powder supplementation group; MIX, combined supplementation group of both VLT powder and BA-9 probiotic.

a,b,c Means without a common superscript differ significantly between the two groups at the same time point (P < 0.05).

VLT and BA-9 alter biomarkers in immune response

Compared with the CON group, BA-9 (P = 0.004) and VLT (P = 0.035) significantly increased the plasma ALB level (Table 3). There was an observed increasing trend in the MIX group compared with the CON group (P = 0.081). There were no significant changes in IgA (P = 0.115), IgG (P = 0.387), IgM (P = 0.257), IL-2 (P = 0.950), IL-4 (P = 0.446), and IL-6 (P = 0.880).

Supplementation of VLT and BA-9 decreases the diversity indices of fecal microbiota

To investigate the combined effects of VLT powder and BA-9 in goat kids, the fecal microbiota was assessed using 16S rRNA sequencing. The amplicon sequencing data were assessed using rarefaction curves. These curves reached a plateau as the sample size increased, indicating that the species distribution within the samples was even and that we had sufficient sequencing depth to cover the major species (Figure S1). This outcome provides a reliable basis for our data and ensures the accuracy of subsequent analyses. We classified all fecal microbiota into 6214 ASVs (Amplicon Sequence Variant)s through amplicon sequencing of the 16S rRNA gene. The Venn diagram illustrates that there were 552 unique ASVs in the CON group, 384 in the BA-9 group, 1072 in the VLT group, and 1071 in the MIX group, with 1173 ASVs shared among all four groups (Fig. 1A). We used the Chao1, Simpson, and Shannon indices to examine the α-diversity of the fecal microbiota (Fig. 1B–D). Compared with the CON group, the MIX group showed significantly decreased Chao1 (P < 0.001), Simpson (P < 0.001), and Shannon (P < 0.001) indices, indicating a lower diversity of microbial species (Fig. 1B–D). We also found significant differences in α-diversity indices between the MIX group and the BA-9 and VLT groups for these indices (P < 0.001). There were no significant differences in Chao1, Simpson, and Shannon indices when the diet was supplemented with BA-9 or VLT alone compared to the CON group. PCoA based on unweighted UniFrac distances showed distinct clustering of samples based on the different treatments (PCoA1 = 28.92%, PCoA2 = 9.93%) (Fig. 1E).

Figure 1. Diversity analysis of fecal microbiota in Nanjiang Yellow Goat kids. (A) Venn diagram of OTUs. (B) Chao 1 index comparing α-diversity among CON, BA-9, VLT and MIX treatment groups. (C-D) Simpson index and Shannon index further confirm significant differences in α-diversity among the groups. (E) PCoA analysis demonstrating intergroup differences in β-diversity. * P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01, *** P < 0.001, **** P < 0.0001.

Comparison of fecal microbial profiling between CON and MIX groups

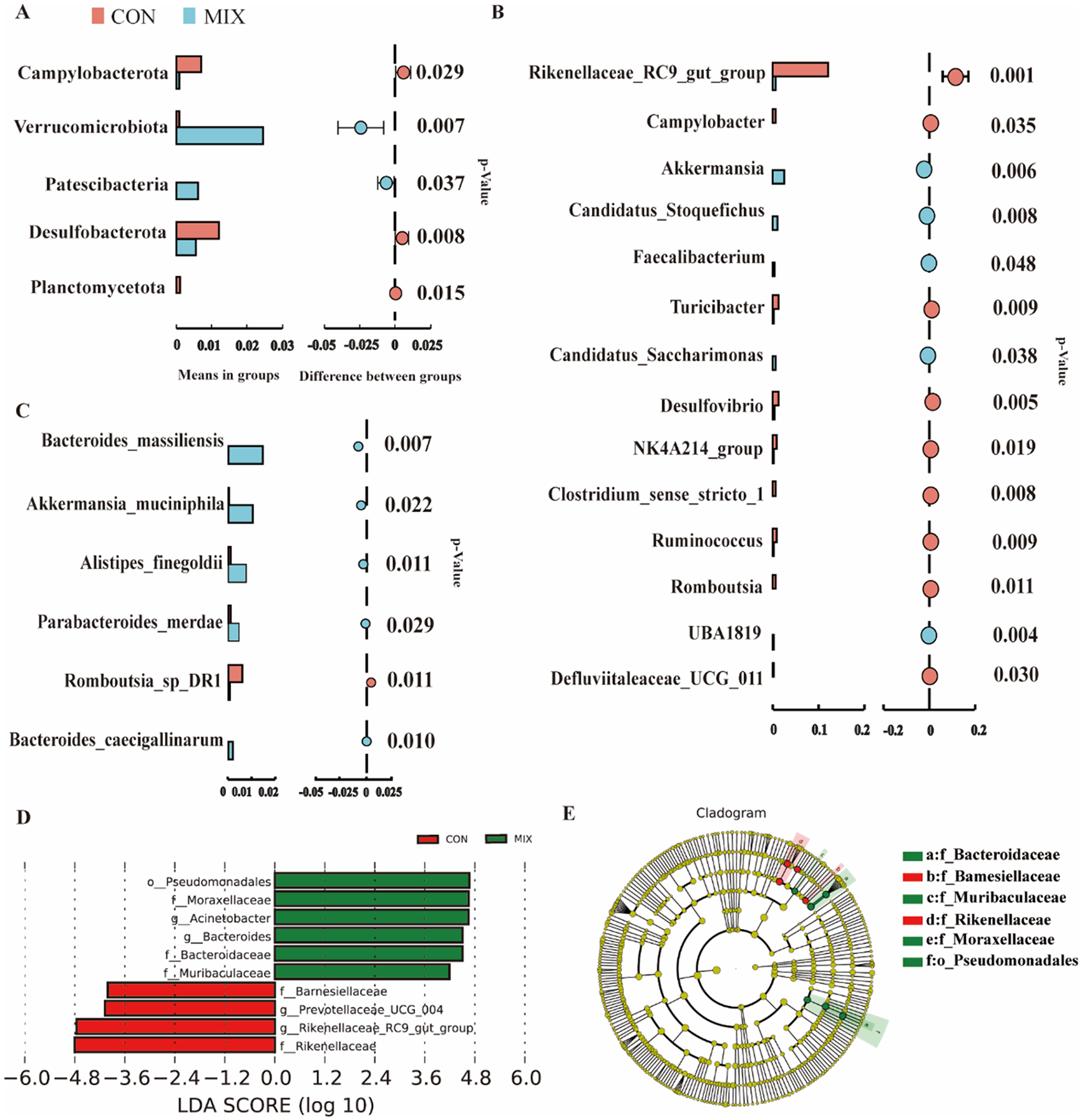

To further explore the combined effects of combination VLT and BA-9 on kids, the microbiota profiling between the MIX and CON groups was compared. At the phylum level, the MIX group showed higher abundances of Verrucomicrobiota (P = 0.007) and Patescibacteria (P = 0.037) compared to the CON group (Fig. 2A). Additionally, the MIX group had lower abundances of Campylobacterota (P = 0.029) and Desulfobacterota compared to the CON group (P = 0.008). At the genus level, the abundances of Akkermansia (P = 0.006), Candidatus_Stoquefichus (P = 0.008), Faecalibacterium (P = 0.048), Candidatus_Saccharimonas (P = 0.038), and UBA1819 (P = 0.004) were significantly increased in the MIX group. Conversely, the abundances of Rikenellaceae_RC9_gut_group (P = 0.001), Campylobacter (P = 0.035), Turicibacter (P = 0.009), Desulfovibrio (P = 0.005), NK4A214 group (P = 0.019), Clostridium_sensu_stricto_1 (P = 0.008), Ruminococcus (P = 0.009), Romboutsia (P = 0.011), and Defluviitaleaceae_UCG_011 (P = 0.030) were significantly decreased in MIX group compared to the CON group (Fig. 2B). At the species level, the MIX group had higher abundances in Bacteroides_massiliensis (P = 0.007), Akkermansia_muciniphila (P = 0.022), Alistipes_finegoldii (P = 0.011), Parabacteroides_merdae (P = 0.029), and Bacteroides_caecigallinarum (P = 0.010) but a lower level of Romboutsia_sp_DR1 (P = 0.011) compared to the CON group (Fig. 2C). Furthermore, the LEfSe further identified differential abundances in bacterial taxa between the MIX and CON groups. The MIX group was enriched with o_Pseudomonadales, f_Moraxellaceae, g_Acinetobacter, g_Bacteroides, f_Bacteroidaceae, and f_Muribaculaceae, while the CON group was enriched with f_Barnesiellaceae, g_Prevotellaceae_UCG_004, g_Rikenellaceae_RC9_gut_group, and f_Rikenellaceae in when LDA was greater than 4. (Fig. 2D–E).

Figure 2. Analysis of the microbial community structure in the CON and MIX groups. (A) Displays the differential bacteria at the phylum level. (B) Displays the differential bacteria at the genus level. (C) Displays the differential bacteria at the species level. (D) Shows the key differential bacteria through Linear Discriminant Analysis (LDA) score plot. (E) The partial phylogenetic tree (Cladogram) reveals the phylogenetic relationships of various microbial categories and their changes in different treatment groups.

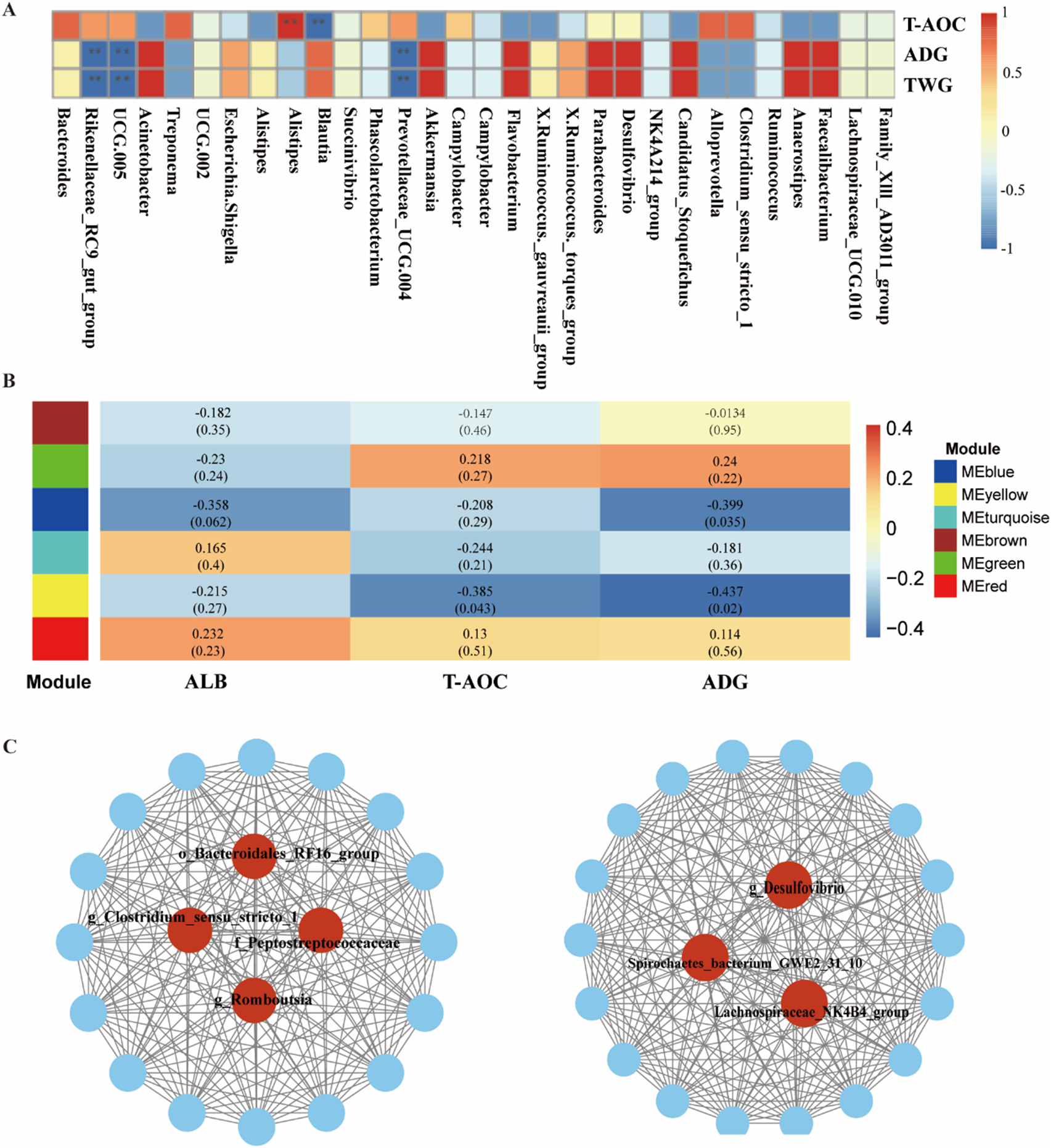

Hub microbiota correlated with growth performance and antioxidant capacity

Spearman’s correlation analysis was conducted to determine the correlation between fecal microbiota and ADG, T-AOC, and ALB at the genus level (Fig. 3A). The results showed that three genera in feces including Prevotellaceae_UCG_004 (P < 0.01, R = −0.77), UCG_005 (P < 0.01, R = −0.53), and Rikenellaceae_RC9_gut_group (P < 0.01, R = −0.58) were negatively correlated with ADG. Alistipes was positively correlated with T-AOC (P < 0.01, R = 0.76), while Blautia was negatively correlated with T-AOC (P = 0.03, R = −0.44).

Figure 3. (A) Correlation between environmental factors and fecal bacteria at the genus level, with * P < 0.05 and ** P < 0.01. Weighted gene co-expression network analysis (WGCNA) was used to analyze the related modules. Correlation networks were generated using Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient. (B) Heatmap of the WGCNA modules. (C) Interaction network and hub microbes in the MEblue and MEyellow modules.

The correlation between ALB, T-AOC, or ADG and the microbial abundance at the genus level was further investigated using WGCNA. A total of six microbiota modules were identified (Fig. 3B). The MEblue was significantly associated with ADG (P = 0.035, R = −0.399), the MEyellow was significantly associated with ADG (P = 0.02, R = −0.437) and MEyellow was significantly associated with T-AOC (P = 0.043, R = −0.385). The network derived from the MEblue module indicated that o_Bacteroidales_RF16_group, g_Clostridium_sensu_stricto_1, f_Peptostreptococcaceae, and g_Romboutsia were the hub microbiota within the MEblue module (Fig. 3C). The network derived from the MEyellow module indicated that g_Desulfovibrio, Spirochaetes_bacterium_GWE2_31_10, and Lachnospiraceae_NK4B4_group were the hub microbiota within the MEyellow module (Fig. 3C).

Discussion

Young livestock are highly susceptible to various diseases because of their immature antioxidant and immune systems, which leads to a low rate of growth performance (Colditz et al. Reference Colditz, Watson and Gray1996; Long et al. Reference Long, Xiao and Zhao2024; Ma et al. Reference Ma, Wang and Wang2021). This study aims to optimize rearing strategies for goat kids by promoting the status of their antioxidant and immune systems through the addition of BA-9 and VLT. Our data found that VLT and BA-9 exhibited significant synergistic effects in promoting the growth performance of goat kids by enhancing the T-AOC. Furthermore, the association analysis demonstrated that combined administration of VLT and BA-9 modulates the fecal microbial community of kids, thereby optimizing their physiological functions and health status.

Young kids, due to their immature digestive and immune systems, are susceptible to environmental changes, often resulting in a low average daily weight gain (Zhang et al. Reference Zhang, Xin and Jiang2021). The increase in average daily weight gain in the VLT group is consistent with previous data in Saanen Kids (Long et al. Reference Long, Xiao and Zhao2024). It is worth noting that when both VLT and BA-9 were added to the kids’ feed, the weight gain effect was superior to that of adding either alone. This indicates a synergistic effect in promoting the growth of kids. One possible reason for this is that chlorogenic acid in LT increases transepithelial electrical resistance and reducing horseradish peroxidase flux, which shows potential in repairing the intestinal barrier and maintaining intestinal health (Wang et al. Reference Wang, Bose and Kim2014). Moreover, BA-9 derived from marine organisms contains various antimicrobial peptides (Li et al. Reference Li, Jiang and Zhang2021). These peptides can enhance the bioavailability of LT by altering the metabolic functions of the gut microbiota or directly improving the overall function of the intestine in young goats. This idea of a synergistic interaction between VLT and BA-9 is further supported by the effects of VLT in promoting the growth of kids. Our data indicate that adding both VLT and BA-9 provides an ideal strategy for promoting the health of young goats.

Our study found that adding VLT and BA-9 to the diet did not impact total protein, triglycerides, or blood glucose levels, indicating that these additives do not influence kids’ nutritional metabolism. However, when VLT and BA-9 were added simultaneously, there was a significant increase in plasma ALB levels in goat kids. This suggests that there is a synergistic effect between these two additives, which may involve complex interactions between intestinal immune regulatory cells and immune signaling molecules. This provides new insights into the regulation of immune function in goat kids (Wang et al. Reference Wang, Bose and Kim2014).

During nutritional metabolism, an amount of reactive oxygen species are produced, which can damage cells and tissues and cause oxidative status (Wang et al. Reference Wang, Liu and Xiao2024). T-AOC and GSH-Px activity are key markers used to assess the antioxidant capacity (Wang et al. Reference Wang, Liu and Xiao2024). The current study showed that adding VLT or BA-9 alone did not affect the antioxidant capacity of goat kids. However, when VLT and BA-9 were fed together, there was a significant increase in T-AOC of kids. This suggests that this combination has an antioxidant activity. VLT and BA-9 may interact to enhance the absorption and utilization of antioxidant components in LT, thereby further enhancing its antioxidant effects.

The observation of a positive correlation between Alistipes and T-AOC agrees with the fact that Alistipes improves gut health and enhances the host’s antioxidant capacity through its metabolic products, such as short-chain fatty acids (Aljumaah et al. Reference Aljumaah, Bhatia and Roach2022). WGCNA revealed microbiome modules significantly associated with ADW and T-AOC, particularly the MEblue and MEyellow modules. The central species within these modules, such as Clostridium_sensu_stricto_1 and Desulfovibrio, may play crucial roles in influencing the growth performance and antioxidant status of kids by modulating the gut microenvironment and affecting host nutrient absorption and energy metabolism. The activity of Desulfovibrio, related to sulfate reduction, impacts the redox state of the gut, thereby influencing the host’s antioxidant capacity (Chen et al. Reference Chen, Lu and Zhu2020). The correlation between the microbiota and antioxidants provides an insight into the interactions between microbiota and growth performance as well as antioxidant status in kids. Future research should further explore the specific mechanisms of action of VLT and BA-9, particularly how they modulate the composition and metabolic activities of the gut microbiota. These data may provide evidence for microbiome-based interventions to optimize livestock growth performance during the early stage of life.

Conclusion

Developing additives that improve the health of young animals can maximize their overall growth performance and productivity throughout their lives. In the current study, our data first underscore the significant improvement in growth performance and antioxidant capacity of goat kids through the combined supplementation of VLT and marine-derived BA-9. This synergistic effect is likely attributed to the modulation of the gut microbiota, as evidenced by significant differences in microbial diversity and the presence of specific bacterial genera that are correlated with growth and antioxidant indices. These findings highlight the potential of using these novel feed additives to enhance the health and productivity of young ruminants, providing a promising strategy for improving livestock rearing practices. Further research should explore the underlying mechanisms of this synergistic interaction to optimize its application in animal husbandry.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/anr.2024.28.

Data availability statement

The datasets presented in this study were deposited in the NCBI Sequence Read Archive (SRA) under the accession PRJNA1143899.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the owners and staff of Nanjiang Yellow Goat Original Breeding Farm (Bazhong, China) for allowing the use of their goats in this experiment and their kind help for the sample collection.

Author contributions

JK: data curation, and writing – original draft. JZ, KL, JW, TL, KZ, and YC: data curation. HS: funding acquisition and supervision, and editing draft. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding statement

This study was jointly supported by Key R&D program of Zhejiang Province (2022C04017 and 2021C02068-6).

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare there are no conflicts of interest.