INTRODUCTION

The transition from the Early Iron Age to the Archaic period in Crete was marked not only by the development of the city-state (polis), but also by profound shifts in the organisation of settlements and in the use of material culture (Gaignerot-Driessen Reference Gaignerot-Driessen2016; Haggis and Fitzsimons Reference Haggis and Fitzsimons2020; Kotsonas Reference Kotsonas, Gleba, Marín-Aguilera and Dimova2021). The concept of a sixth-century Cretan decline from a seventh-century cultural and artistic floruit was first outlined in detail in the 1940s, most evocatively by Levi (Reference Levi1945; see also Demargne Reference Demargne1947), who described the pottery and metalwork of the late seventh century as ‘the last flight of imagination of the old civilization of Crete before it settles into the darkness of its exhausted, lethargic sleep’ (Levi Reference Levi1945, 18). In the 1990s and early 2000s, the sixth century received monikers like ‘the Archaic gap’(Coldstream and Huxley Reference Coldstream and Huxley1999), ‘the period of silence’ (Stampolidis Reference Stampolidis1990, 400; I. Morris Reference Morris, Fisher and van Wees1998), ‘the best candidate for being a Dark Age’ (Coldstream Reference Coldstream, Musti, Sacconi, Rocchetti, Scafa, Sportiello and Gianotta1991, 298; Prent Reference Prent, Maaskant-Kleibrink and Vink1996), a time of ‘laws without cities’ (Whitley Reference Whitley2001, 243), or even the period when ‘Archaic Cretan culture disappear[ed]’ (S.P. Morris Reference Morris1992, 169). Some proposed that these changes were caused by the disruption of Mediterranean trade networks after Babylonia's defeat of Assyria (e.g., S.P. Morris Reference Morris1992, 169–72). Others focused on internal factors: the political weakness of Cretan city states, civil discord, or even a war between ‘Dorian’ and ‘Eteocretan’ ethnic elements in Cretan culture (Levi Reference Levi1945, 18; Demargne Reference Demargne1947, 352–3). Most explanations emphasised isolationism, economic primitivism, and cultural backwardness. Cut off from the wider Mediterranean world, Crete remained stuck in an early stage of evolutionary development, a tribal aristocracy that would never approach the economic and political achievements of Classical Athens (e.g., Willetts Reference Willetts1955, 249–56).

Recent archaeological work on the island has shifted these older narratives. Excavations at Azoria and Itanos in east Crete have yielded Archaic civic and domestic architecture, artefact assemblages, and a funerary building (Haggis et al. Reference Haggis, Mook, Fitzsimons, Scarry and Snyder2007; Reference Haggis, Mook, Fitzsimons, Scarry and Snyder2011a; Reference Haggis, Mook, Fitzsimons, Scarry and Snyder2011b; Tsingarida and Viviers Reference Tsingarida, Viviers, Lemos and Tsingarida2019). Significant progress has been made towards establishing various local Cretan ceramic sequences for black-gloss fineware of the sixth and fifth centuries BCE (Erickson Reference Erickson2010). Ongoing projects that combine archival study, analysis of previously excavated material, and new fieldwork at the important Cretan settlements of Prinias, Phaistos, Gortyn, Lyktos, Aphrati, and Onithe Gouledianon are already contributing more to our archaeological knowledge of the period (Pautasso et al. Reference Pautasso, Rizza, Pappalardo, Hein, Biondi, Gigli Patané, Perna and Guarnera2021; Pautasso and S. Rizza Reference Pautasso and Rizza2023; Bredaki and Longo Reference Bredaki and Longo2018; Allegro and Anzalone Reference Allegro and Anzalone2016; Kotsonas, Sythiakakis and Chaniotis Reference Kotsonas, Sythiakakis and Chaniotis2021; Biondi Reference Biondi, Niemeier, Pilz and Kaiser2013; Psaroudakis Reference Psaroudakis2015).

However, the sixth-century ‘gap’ has been stoutly defended at Knossos, one of the most intensively explored urban centres on the island. Coldstream and Huxley (Reference Coldstream and Huxley1999) proposed a major demographic decline and economic recession beginning with the abandonment of the rich Early Iron Age North and Fortetsa Cemeteries c. 630 BCE. They observed a paucity of sixth-century votives at the Sanctuary of Demeter on Gypsades hill and a lack of preserved architecture and stratified deposits from this period in the settlement. Erickson (Reference Erickson2010, 238; Reference Erickson2014, 80–1), who has restudied many of the Knossian deposits, maintains the existence of a gap in the ceramic record between 590 and 525 BCE. Proposed reasons for Knossos’ decline in the sixth century have include plague, drought, crop failure, stasis, a military conflict with Lyktos or Gortyn, or some combination of these factors (Dunbabin Reference Dunbabin1952, 196–7; Huxley Reference Huxley, Eveley, Hughes-Brock and Momigliano1994, 128–9; Coldstream and Huxley Reference Coldstream and Huxley1999, 303–4; Erickson Reference Erickson2010, 239–43). Though a missing 65 years at a site continuously occupied since 7000 BCE may seem like a small matter, the consequences of the ‘gap’ have been far-reaching. The Knossian sequence remains an important point of comparison for other Cretan assemblages due to the long history of excavations at the site and the volume of published material. A revised understanding of Archaic Knossian material culture therefore not only improves our knowledge of the city's history, but also has implications for the dating of Protoarchaic and Archaic material at other Cretan sites.

In this article, I re-evaluate the historical and archaeological narrative of the sixth-century Knossian gap through analysis of published and unpublished material from four well deposits in the Stratigraphical Museum at Knossos, as well as associated excavation notebooks in the Knossos Archive. These deposits were published highly selectively and were originally dated to either the late seventh or early fifth centuries BCE. I first describe these deposits and contextualize them within the wider Knossian settlement. I then present the results of my study, in which I identify likely traces of mid-sixth-century material. I conclude with a discussion of possible causes for the patterns in material culture we observe in sixth-century Knossos and across Crete in general, arguing for an explanation of low archaeological visibility that emphasises cultural choice and shifting patterns of settlement rather than environmental catastrophe, political strife, or economic decline. While the concept of ‘austerity’ has previously been invoked to describe a purported cultural restraint in Archaic Crete (especially central Crete), I suggest that ‘conservatism’ may be a more accurate term to characterise trends in material culture at Knossos and other Cretan sites. This conservatism may take the form of (1) deliberate retention and curation of artefacts over a significant period of time (perhaps multiple generations) or (2) the continued production of artefacts in older styles, including styles associated with the seventh century or even earlier. By placing the finds from Knossos within their wider Cretan context, I question the epistemological foundations on which the gap has been constructed and propose more nuanced alternative explanations for the difficulty of identifying mid-sixth-century ceramics at the site.

A note on terminology is warranted here. Publications of the material from the Knossos settlement use the term ‘Orientalising’ when referring to ceramics of the seventh century, with ‘Early Orientalising’ extending from c. 700 to 670 BCE and ‘Late Orientalising’ from c. 670 to 630 BCE (Coldstream Reference Coldstream, Coldstream, Eiring and Forster2001, 22). However, ‘Orientalising’ is properly a stylistic rather than a chronological designation (Whitley Reference Whitley, Niemeier, Pilz and Kaiser2013), and it fails to consider the specific contexts in which certain styles were deployed.Footnote 1 Much seventh-century domestic pottery from Knossos is decorated with simple geometric motifs (bands and concentric circles) similar to those from preceding centuries rather than the human–animal hybrids and elaborate decorative elements (guilloche, tree, lotus, rosette, palmette) that are typically associated with ‘Orientalising’ pottery styles and occur in abundance in the Early Iron Age Knossian cemeteries (Coldstream and Macdonald Reference Coldstream and Macdonald1997, 237–8; Coldstream Reference Coldstream, Coldstream, Eiring and Forster2001, 70–2). For ceramics, ‘Orientalising’ styles occur only on painted fineware or relief pithoi, further eroding the utility of the term. I therefore use ‘Protoarchaic’ or simply ‘seventh century’ to designate the seventh century as a chronological period (Brisart Reference Brisart2011, 17–18; Charalambidou and Morgan Reference Charalambidou, Morgan, Charalambidou and Morgan2017, 1).

ARCHAIC KNOSSOS: THE SIXTH-CENTURY EVIDENCE

In terms of new excavation data at Knossos itself, little has changed since Coldstream and Huxley first articulated the concept of a Knossian gap nearly 25 years ago. Most late seventh- through early fifth-century pottery from the Knossos settlement is not associated with architecture, but comes instead from well deposits, pit fills, or scrappy use surfaces. In addition to the wells from the Royal Road North and Unexplored Mansion discussed below, two other areas of the settlement deserve mention (Fig. 1). First, excavations at the Southwest Houses south-west of the Minoan palace produced a kiln, fragmentary walls and domestic pottery dating from 700 to 625 BCE; a Late Archaic pit fill; three stratified floors or walking surfaces dating to the Late Archaic to Early Classical periods; and a Classical road (c. 450 BCE) (Coldstream and Macdonald Reference Coldstream and Macdonald1997, 237–42). Second, the so-called ‘Shrine of Glaukos’, which functioned as a cult building in the Classical and Hellenistic periods, was located directly above a seventh-century building with a floor, shallow hearth, and seemingly domestic assemblage of jugs, cooking pots, trays, loomweights and spindle whorls (Callaghan Reference Callaghan1978, 1). During the second phase of the building, new walls and a new floor were constructed above the seventh-century house but below the Classical and Hellenistic shrine. This floor yielded lekanes, pithos sherds and a sherd of a louterion or fenestrated stand, suggesting ritual activity. Though this material remains unpublished, Callaghan (Reference Callaghan1978, 3) suggested on stratigraphic grounds that this phase might belong to the sixth century. It is worth noting that the Azoria excavations also recovered fenestrated stands in rooms A800, A1200 and A1400 of the sixth-century Communal Dining Building, where the excavators hypothesised that they were used to support kraters during ceremonial feasts (Haggis et al. Reference Haggis, Mook, Scarry, Snyder and West2004, 380–2).

Fig. 1. Map of Knossos showing sites discussed in the text. After Hood and Smyth Reference Hood and Smyth1981. Reproduced with the permission of the British School at Athens.

A handful of isolated finds from the Knossos area have been dated stylistically to the sixth century. An elaborate bronze vessel decorated with gorgons, found together with an Attic black-figure hydria and skyphos during excavations to lay a water pipe west of the road to Heraklion in 1936, may have belonged to a late sixth-century burial (Boardman Reference Boardman1962, 28–30; Hood and Smyth Reference Hood and Smyth1981, 35–6). More recently, a small and poorly preserved statue head of poros limestone was recovered from a Roman robbing pit near the Little Palace North (Whitley Reference Whitley2002–3, 81–2, fig. 134). While the excavators dated the sculptures to the mid-sixth century, it has also been dismissed as an Archaising Roman statue or a foreign object brought to Crete after the Archaic period (Erickson Reference Erickson2014, 82–3) – though it is difficult to square the latter suggestion with the excavators’ conviction that the statue's material is local.

Recent re-analysis of previously excavated Knossian deposits has also challenged the assertion that Knossos saw a ‘definite gap in the import record ca. 600–525 BC’ (Erickson Reference Erickson2010, 238). Paizi's (Reference Paizi2023) new study of pottery from pit fills at the Unexplored Mansion, all of which were originally dated to the Late Archaic period (525–475 BCE; Callaghan Reference Callaghan1992, 89–92), has identified multiple imports dating to the mid-sixth century, including an Attic black-figure Little Master cup (550–525 BCE), an Attic black-figure krater (550–525 BCE), a Corinthian kotyle (560–540 BCE), two Corinthian powder pyxides (600–550 BCE) and a Lakonian krater (575–525 BCE). These can now be added to another known import from these years: an Attic black-figure banded cup from upper fill in the Royal Road North excavations (550–525 BCE), which I discuss further below (Coldstream Reference Coldstream1973, 63, no. 17). While the number of sixth-century imports from Knossos relative to the intensity with which the site has been explored may still seem relatively small when compared to some other Cretan sites, such as Eleutherna (Erickson Reference Erickson, Day, Mook and Muhly2004; Reference Erickson2010, 51–77), Itanos (Tsingarida and Viviers Reference Tsingarida, Viviers, Lemos and Tsingarida2019, 219–23), Phalasarna (Gondicas Reference Gondicas1988, 108) or Olous (Apostolakou and Zographiki Reference Apostolakou, Zographiki, Tabakaki, Kaloutsakis, Detorakis and Kalokairinos2006), the most economical explanation for their presence in these fills is that some Knossians acquired sympotic and cosmetic vessels from abroad over the course of the sixth century.

As Paizi's work demonstrates, the absence of substantial deposits clearly associated with residential or civic contexts means that well and pit fills are our primary evidence for the ceramic assemblages of Archaic Knossos. These features also provide some clues to the topography of the Archaic settlement: we can assume that they are located near the habitations or public buildings where the pottery in their fills was once used. Yet analysing well deposits requires that we think closely about the formation processes shaping them. In theory, wells contain a ‘use deposit’ at the bottom marked by a concentration of abandoned water vessels, followed by one or more layers of dumped fill; however, the reality may depart substantially from this ideal (Robinson Reference Robinson1959, 123; Brann Reference Brann1962, 107–8; Sparkes and Talcott Reference Sparkes and Talcott1970, 44–5). Fill may be deposited rapidly when wells fail during a drought (e.g. Brann Reference Brann1962, 108; Camp Reference Camp1979) or during a clean-up event after a major destruction (e.g. Lynch Reference Lynch2011, 22). Alternatively, well fill may represent a gradual, long-term process. Many joins between upper and lower levels suggest a single fill event, while fewer joining sherds between levels imply a more gradual process (though even here we should account for the possibility of small sherds slipping lower into the fill).

A lack of securely dated and thoroughly published sixth-century Cretan contexts presents a further difficulty. While Erickson's (Reference Erickson2010) groundbreaking study of Cretan finewares is to be commended for its detailed analyses of previously overlooked material, his criteria for dating material are largely stylistic rather than stratigraphic. The deposits from the Orthi Petra cemetery at Eleutherna, though stratified above Early Iron Age and Protoarchaic burials, are from heavily disturbed contexts that could represent either the remains of tombs or ritual meals. The sherds from Gortyn are described as ‘residual’ material from the area of the Late Hellenistic Odeion, yet dated very narrowly, mostly within 25-year intervals (Erickson Reference Erickson2010, 178). It is admirable and necessary to make use of these deposits, but the dating may need to be approached with greater humility until well-stratified Archaic Cretan assemblages are more comprehensively published. In particular, defining a gap in occupation at Knossos based on this narrow chronological scheme is unwarranted.

On Crete, the most promising sites for gaining a better understanding of sixth-century material culture across a wide range of functional contexts are Azoria and Prinias. Azoria witnessed a major urban expansion and restructuring at the end of the seventh century BCE, during which Archaic houses and civic buildings were constructed. It was abandoned in the first quarter of the fifth century and suffered relatively little post-depositional disturbance (Haggis et al. Reference Haggis, Mook, Fitzsimons, Scarry and Snyder2011b, 438; Haggis Reference Haggis2014). Detailed preliminary reports provide a glimpse of sixth- and early fifth-century Cretan assemblages at the site. It is clear from these publications that certain ‘Orientalising’ artefacts once strongly associated with the seventh century, such as Daedalic figurines and relief pithoi, continued to be used into the early fifth century at Azoria (Haggis et al. Reference Haggis, Mook, Fitzsimons, Scarry and Snyder2011b, 468–9, fig. 27:1). The retention or continued manufacture of relief pithoi as late as the Hellenistic period has been documented at several other Cretan sites, including Lyktos, Phaistos, Arkalochori, Trypetos, and even Knossos itself, where Archaic relief pithoi and tiles were found at the bottom of a well at the Unexplored Mansion that was otherwise filled with pottery of the late third and early second centuries BCE (Callaghan Reference Callaghan1981, 36; Vogeikoff-Brogan Reference Vogeikoff-Brogan2011, 555; Galanaki, Papadaki, and Christakis Reference Galanaki, Papadaki, Christakis, Haggis and Antonaccio2015; Reference Galanaki, Papadaki and Christakis2019).

The settlement on the Patela at Prinias in central Crete, about 25 kilometres south of Knossos, was abandoned several decades into the first half of the sixth century BCE, a stratigraphic horizon marked across the settlement by a rocky layer of wall collapse (G. Rizza Reference Rizza2008, 299–301; Pautasso and S. Rizza Reference Pautasso and Rizza2023, 21–5). A final occupation date of c. 570 BCE is provided by a Middle Corinthian amphoriskos found in Room C of the Patela settlement (G. Rizza Reference Rizza2008, 150, no. C61, fig. 117). In a new synthesis of the architecture and finds from the architectural complexes on the Patela, Pautasso and S. Rizza (Reference Pautasso and Rizza2023) identify locally produced pottery from the first decades of the sixth century, dated based on comparison to deposits from Azoria and the cemeteries at Tarrha and Aphrati, including cups (nos 22, 23, 629), a lekanis (no. 683), a straight-sided pyxis (no. 19), a coarse ware lekane (no. 554) and cooking pots (nos 41, 396, 407). Two lamps from the final occupation levels of rooms on the Patela can also be dated to the first half of the sixth century. The first, a semi-circular marble lamp (G. Rizza Reference Rizza2008, 125, no. A10, pl. 64) finds a close parallel in a lamp from a grave in Kamiros, found in association with an Attic lekanis of 575 to 525 BCE (Beazley Reference Beazley1940, 36–7, no. 7, figs 6 and 7). The second terracotta lamp with an incurving rim, flattened base, and large fill hole, partly dipped in red paint (G. Rizza Reference Rizza2008, 243, no. AS27, pl. 152), is similar to Type 1 lamps from Corinth dating between 600 and 550 BCE (see especially Broneer Reference Broneer1930, 132, no. 37, fig. 57). The Prinias settlement's final phase thus extends several decades past the beginning of the putative Knossian ‘gap’.Footnote 2

In light of these recent developments in our understanding of Archaic Cretan material culture, a reassessment of the Knossian ‘gap’ is necessary. In what follows, I focus on four Knossian wells from two different areas north-west of the Minoan palace (Fig. 1). The first two were exposed during excavations north of the Royal Road in 1960: Well LA (Deposit J) and Well H (Deposit L) (Coldstream Reference Coldstream1973, 42–3, 48–60). The second two come from the Unexplored Mansion excavations of 1973: Well 8a (Deposit GG) (Coldstream Reference Coldstream1992, 75, 85–6) and Well 12 (published separately from the rest of the Unexplored Mansion in Coldstream and Sackett Reference Coldstream and Sackett1978, 49–60) (Table 1). The Stratigraphical Museum at Knossos houses material from these wells, including many unpublished finds (some of which are presented here). Ceramics from all wells except UM Well 12 were highly selected for feature sherds, decorated wares, and imports, with no indication of stratigraphic level or depth within the well – a fact that unfortunately disallows much quantitative analysis. However, placing these deposits back in their local and regional contexts enhances our understanding of the archaeological assemblages and cultural history of Knossos in the sixth century. If concentrated deposits of mid-sixth-century imports and unimpeachably clear evidence of local mid-sixth-century pottery production are demanded to close the 590 to 525 BCE gap at Knossos, then this is indeed difficult to achieve given the current state of the evidence – and it would be challenging to definitively produce this type of evidence at many other Cretan sites as well.Footnote 3 In what follows, I approach the problem by comparing published and unpublished material from these Knossian wells to other assemblages of sixth-century Cretan pottery (from Azoria, Prinias, Tocra, Tarrha, Eleutherna, Praisos and other sites). In so doing, I suggest a plausible new interpretation of the material culture patterning visible at Archaic Knossos.

Table 1. Summary of four well deposits at Knossos.

WELLS LA AND H FROM THE ROYAL ROAD NORTH EXCAVATIONS

Wells LA and H are located north of the Minoan Royal Road and directly west of the Palace Armoury or Arsenal (Fig. 1). This area was investigated by Sinclair Hood between 1957 and 1961 with the goal of clarifying Arthur Evans’ Minoan chronology, but the excavations have not yet been fully published. Preliminary reports describe a house with Hellenistic and Roman phases located above substantial earlier material: Early Minoan levels, the remains of a Late Minoan IB ivory workshop, a Geometric terrace wall, and multiple post-Minoan wells and pits, including Wells LA and H (Hood Reference Hood1957, 21; Reference Hood1958, 20; Reference Hood1959, 24; Reference Hood1960, 26–7; Hood and Smyth Reference Hood and Smyth1981, 51; Hood et al. Reference Hood, Cadogan, Evely, Isaakidou, Renfrew, Veropoulidou and Warren2011, 75–80). Well LA was located roughly eight metres due east of Well H, against the eastern baulk of the excavations (Fig. 2). These well deposits were later selectively published by Coldstream (Reference Coldstream1973) as part of a larger synthesis of Orientalising and Archaic pottery from the Knossos settlement, and Erickson (Reference Erickson2010, 122–67) restudied some of the finds from Well H.

Fig. 2. Drawing of the Royal Road north excavations, showing locations of Well LA (against east baulk) and Well H (located at the centre of the excavations). British School at Athens Archives, Sinclair Hood Papers (uncatalogued), drawing, Armoury Royal Road, Folder ‘RR:N/POTY 2 SFs ETC/DE 2 SH’, inventory number S3gA.02. Reproduced with the permission of the British School at Athens.

Preliminary reports and unpublished excavation notebooks refer to sixth-century material at Royal Road North. Reporting on the 1958 excavations, Hood (Reference Hood1958, 20) described ‘pits filled with stones dating from the 6th or 5th centuries BC’, which he interpreted as the remains of agricultural field clearance. These pit fills must have contained ceramics for Hood to posit a date, though this material does not appear to have been retained in the Stratigraphical Museum. In a pottery notebook from the 1960 excavations, a note in Coldstream's handwriting records the discovery of the mid-sixth-century Attic black-figure banded cup discussed above in upper fill in Trenches H and LA (where wells H and LA are located) (British School at Athens Archives, Sinclair Hood Papers [uncatalogued], inventory number S3gB.22, 2; Coldstream Reference Coldstream1973, 63, no. 17). Though clearly out of context, this is a rare example of an Attic import of 550 to 525 BCE at Knossos. Sixth-century pottery is also documented in three other mixed deposits from Trenches H and JKE (Sinclair Hood Papers, inventory number S3gB.27.G, 9, 27).

Hood (Reference Hood1958, 22) observed that, in the Archaic and Classical periods, ‘the whole of this area on both sides of the Royal Road appears to have been open ground with fields or gardens outside the city limits’. Neither well was associated with contemporary floors, use surfaces, or buildings. There is thus no indication that Wells LA and H were located in the courtyards of houses that no longer survive, as was once argued for the Early Iron Age and Archaic wells in the Athenian Agora (Brann Reference Brann1962, 108; Camp Reference Camp1986, 33; cf. Papadopoulos Reference Papadopoulos2003, 273–5). While our evidence for Cretan house plans in the sixth and fifth centuries is slim, no Cretan houses from the more thoroughly documented seventh century possess interior wells, apart from a possible example in the courtyard of Building III on the Profitis Ilias hill at Gortyn (abandoned in the late seventh or early sixth century BCE; Allegro Reference Allegro, Andriankais and Tzachili2010, 328–9). We therefore should not assume that the fills of Well LA and Well H represent the discard of individual households. However, these wells were probably not located ‘outside the city limits’, as Hood (Reference Hood1958, 22) argued. The recent work of the Knossos Urban Landscape Project (KULP), an intensive pedestrian survey of 11 square kilometres around the urban centre, has demonstrated that Knossos likely extended over a large area of 50 to 60 hectares in the Early Iron Age, Archaic, and early Classical periods (Kotsonas Reference Kotsonas2019; Trainor Reference Trainor2019). The seventh- to fifth-century settlement certainly encompassed the area north-west of the palace where the Royal Road and Unexplored Mansion wells were located. These wells were thus in the midst of the settlement and were likely used for domestic refuse disposal by one or more households, in addition to receiving debris from other structures (as will be discussed in relation to Well H). I now turn to consider the contents of each of these two wells.

Well LA

Well LA (RR/LA/60) was excavated in 1960 to a depth of 8.2 metres. The bottom of the deposit was not reached. The fill was dated to between 650 and 620 BCE based on two Corinthian imports – an aryballos with an incised scale pattern and a late seventh-century kotyle – and two local imitations of Corinthian black figure, all very fragmentary (Coldstream Reference Coldstream1973, 34–5, 43). This dating leaves the sixth-century Knossian gap intact. However, setting the date for the entire fill of Well LA using only these objects is problematic. Small and elaborate personal items, like the aryballos, may have been retained for some time before being discarded. Given that Corinthian imports were not terribly frequent in this assemblage during the seventh century (two recognisable examples from a deposit over eight metres in depth), the absence of sixth-century Corinthian imports in the fill is unlikely to be very meaningful. No joins between sherds in the upper and lower parts of the deposit are mentioned, and it is possible that the well was filled over a period lasting longer than just a few decades in the late seventh century.

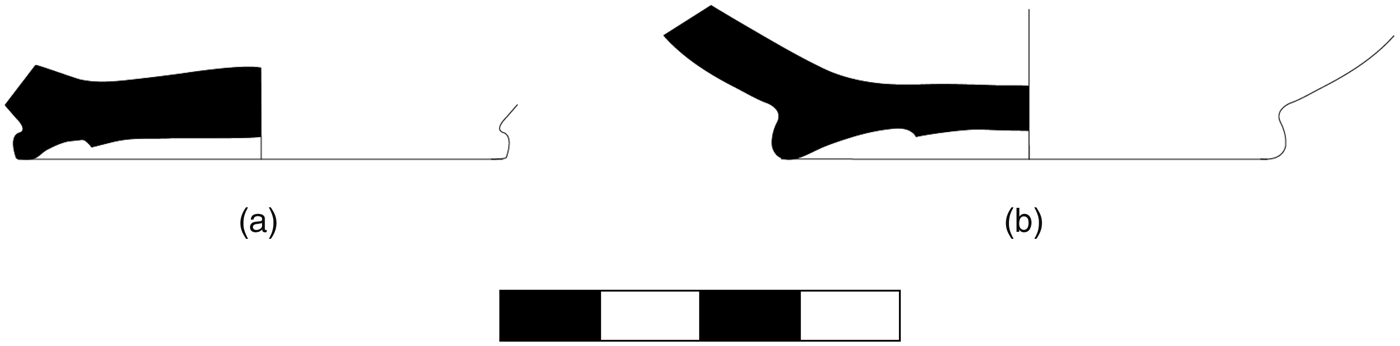

Several other observations throw the dating of Well LA into question. One published cup from the deposit has a distinctive base with a splayed foot and an applied disc on the underfoot (Coldstream Reference Coldstream1973, 43, no. J33, fig. 3). Coldstream reported seven other similar unpublished cup bases in the deposit; I observed two that fit this description (Figs 3 and 4). The presence of multiple examples of this cup type in Well LA is notable because Erickson (Reference Erickson2010, 128–9) treats this shape (‘an articulated disk foot with a stepped profile underneath’) as a type fossil for the last quarter of the sixth century BCE on Crete. After first identifying the shape at Knossos, Erickson dates all cups of this type across the island to the years between 525 and 500 BCE, including examples from residual deposits at Gortyn (Erickson Reference Erickson2010, 179, nos 408–13, fig. 6:1), a Gortynian import at Eleutherna (Erickson Reference Erickson2010, 84, no. 114, fig. 3:19–20), and a large concentration from Praisos Survey site 14 (Erickson Reference Erickson2010, 213–14, nos 510–24, fig. 8:10). The use of applied discs on the underfoot of cups finds a precedent in mid-sixth-century Cretan cups, such as an example from Level 7 at Tocra in Libya, dated from 565 to 520 or 510 BCE.Footnote 4 This example has a simple hollow base rather than a splayed foot, however, and thus does not fall properly into Erickson's late sixth-century category.

Fig. 3. Profile drawings of cup bases (a) and (b) with stepped profile underfoot from Royal Road North, Well LA.

Fig. 4. Photographs of the interior and exterior of cup bases (a) and (b) with stepped profile underfoot from Royal Road North, Well LA.

Cups with a splayed foot and an applied disc underfoot can be found in earlier Cretan contexts, however. Two such bases have been published from Archaic Building Q at Kommos, where this cup shape was one of the two most common in the deposit.Footnote 5 The abandonment of Building Q was dated to around 600 BCE based on a scarcity of sixth-century imports (Johnston Reference Johnston1993, 374–5). Yet activity at the wider sanctuary continued into the sixth century, with a new altar (Altar H) constructed around 550 BCE (Callaghan and Johnston Reference Callaghan, Johnston, Shaw and Shaw2000, 253). Cups found in mixed contexts across the site with low splayed feet, several with an applied disc underneath, were interpreted as likely sixth-century products, with one example from Altar H (no. 419) argued to predate late sixth-century cups at Knossos (Callaghan and Johnston Reference Callaghan, Johnston, Shaw and Shaw2000, 251–3, nos 397, 413, 415, 416, and 419, pl. 4:19,20). At Kommos, then, there appears to be strong continuity in this cup type across the sixth century, at least with respect to the morphology of the cup base: it is hard to detect a pronounced difference between the late seventh-century cups of Building Q and the sixth-century cups from Altar H and other areas of the site.

To return to Well LA at Knossos, it would be possible to dismiss all cup bases of this type in the well as post-525 BCE intrusions, thereby defending both the late seventh-century date for the well deposit as a whole and the sixth-century gap of 590 to 525 BCE. However, the presence of multiple examples of these bases among the retained pottery makes this interpretation less likely: instead, a date for these cups in the early or mid-sixth century seems most probable. Furthermore, some of the Well LA cups unite seventh-century decoration with sixth-century shapes. One example (Figs 3b and 4b) combines a splayed foot and stepped-profile underfoot with a dark ground and painted white bands on the interior and exterior. Light-on-dark concentric circles, lines, and bands are a typical decorative scheme for seventh-century pottery from the Knossos settlement (Coldstream and Macdonald Reference Coldstream and Macdonald1997, 237–9). This may suggest that some of the decorative styles associated with the seventh century at Knossos persisted into the sixth century.

Chronologies for utilitarian and storage wares are less well-developed than those for drinking and serving vessels, and their forms tend to persist over longer periods of time. Nevertheless, several larger shapes in Well LA could also belong to the sixth century, including a lekane manufactured in the local pink fineware fabric with smoothed surface (Fig. 5). The vertical folded rim with mouldings and flattened lip recalls the rim of several open vessels from Prinias, including one stratigraphically associated with the mid-sixth-century marble lamp discussed above (G. Rizza Reference Rizza2008, 125, no. A1, pl. 64; Pautasso and S. Rizza Reference Pautasso and Rizza2023, 121, no. 554, pl. 30), as well as a basin rim from the kitchen of the Service Building for the Monumental Civic Building at Azoria (Haggis et al. Reference Haggis, Mook, Fitzsimons, Scarry and Snyder2007, 282, fig. 29:4).

Fig. 5. Folded lekane rim from Royal Road North, Well LA.

Decorated pithos fragments (including many unpublished examples) were also retained from Well LA in two main fabrics: a light red fabric with much vegetal temper, often with a creamy light pink slip applied to the surface, and a darker red fabric with inclusions of schist and silver mica. The micaceous pithos fabric likely comes from the Pediada region, south-east of Knossos (Kotsonas Reference Kotsonas2019, 2–3). Decorative motifs on these pithoi included stamped plain circles, stamped concentric circles, raised bands (plain and slashed), finger-traced spirals, wheels, and stamped framed rosettes. Many of these same motifs are also attested on pithoi at Azoria (Donald Haggis, pers. comm.) and at the kiln site of Mandra di Gipari at Prinias, which was in operation as a production centre from the late seventh until the early decades of the sixth century BCE (Rizza, Palermo, and Tomasello Reference Rizza, Palermo and Tomasello1992, 107, pls 10–16). Though these pithoi often employ ‘Orientalising’ decoration, the use lives of these objects frequently extend into the sixth and fifth centuries BCE or even later, as discussed above – implying either the curation of Protoarchaic and Archaic pithoi as ‘heirlooms’ (Whitley Reference Whitley, Nevett and Whitley2018, 62) or, potentially, continued traditions of manufacture beyond the seventh century. Unfortunately, few Cretan relief pithoi are complete and have a secure archaeological provenience, and refining our understanding of their chronology and production histories remains a desideratum that is beyond the scope of this paper. Here, I note that their appearance in the well is compatible with a post-seventh-century date and that very similar vessels also appear on the other side of the purported ‘gap’ (see below).

Well H

Unlike Well LA, Well H was excavated to its full depth of 12 metres. The large quantity and variety of Attic black-figure and black-gloss imports in this well is unusual for Knossos and for other Archaic Cretan contexts: 33 out of 116 of the published pots from this deposit were Attic, and I observed another kilogram of Attic material among unpublished finds. Most of this Attic material was found near the bottom of the well, in the lowest three metres, but many joins in locally produced ceramics were found between layers (Coldstream Reference Coldstream1973, 46). For this reason, the entire fill was dated to the Late Archaic period, c. 500–480 BCE, based on the Attic pottery. While this narrow dating is plausible for many of the Attic imports, some would comfortably accomodate a slightly earlier date. An Attic column krater with a scene of Herakles framed by ivy, for instance, finds its closest parallels with Attic pottery of the late sixth century BCE rather than the early fifth (Coldstream Reference Coldstream1973, 57–8, no. 76, pls 22–3; see Moore, Philippides and van Bothmer Reference Moore, Philippides and Bothmer1986, 160–1, nos 471, 474, 476, pls 44–5). The Attic imports alone, however, do not appear to extend earlier into the sixth century than 525 BCE.

The retained assemblage from Royal Road Well H shows marked changes from the Well LA assemblage. High-necked cups with black or red gloss, absent in Well LA, are now a prevalent shape, and the cup type with splayed foot and stepped profile underfoot is absent. Other locally produced ceramics, however, may date to earlier in the sixth century. Five published lamps (Coldstream Reference Coldstream1973, 55–7, nos 71–5, fig. 10) and at least five other unpublished ones have large fill holes, baggy sides, and projecting rims that often slant inward (Figs 6 and 7). All are made in local Knossian fabric. While Erickson (Reference Erickson2010, 167, nos 375–7, fig. 5:1) reaffirmed a date of 500 to 480 BCE for the lamps from Well H, the closest parallels are Type II lamps from Corinth (sixth century BCE) and Type 12A lamps from the Athenian Agora dated between 575 and 525 BCE (Broneer Reference Broneer1930, 32, no. 11; Howland Reference Howland1958, 25–6, nos 71–2; Bookidis and Pemberton Reference Bookidis and Pemberton2015, 52, no. L57).

Fig. 6. Lamps L71–L75 from Royal Road North, Well H. Published in Coldstream Reference Coldstream1973, 55–7, fig. 10. (a) L71; (b) L75; (c) L73; (d) L72; (e) L74.

Fig. 7. Unpublished lamps from Royal Road North, Well H.

While we might expect some time lag between the Corinthian or Attic lamp production sequence and the adoption of a similar shape in Cretan sequences, it is notable that Eleuthernian lamps extremely similar to the Knossian Well H examples have been dated broadly to the sixth century rather than to a narrow band in the early fifth (e.g. Erickson Reference Erickson2010, 169–70, nos 386–90, fig. 5:2). A similar lamp with a wide fill hole and flattened rim bevelled to the interior was found in the porch of the Communal Dining Building at Azoria, part of a deposit consisting of residual debris discarded from adjacent dining rooms spanning the sixth and early fifth centuries (Haggis et al. Reference Haggis, Mook, Fitzsimons, Scarry and Snyder2007, 257–8, fig. 11:1). Other lamps of the same shape, possibly of East Greek manufacture, were found at Tocra and dated to the mid-sixth century based on both stratigraphic associations and abundant parallels.Footnote 6 Previous studies of the Knossian lamps from Well H have preferred to characterise them as ‘old-fashioned’ (Coldstream Reference Coldstream1973, 48) or emblematic of ‘Cretan conservativism in the field of lamp production’ (Erickson Reference Erickson2010, 167) rather than sixth-century in date, but in any other Aegean context, lamps of the type found in Knossos Well H would be assigned to the middle of the sixth century. It is not unreasonable to suggest that such a lamp type at Knossos should be broadly dated to the sixth century, rather than within a narrow band of 20 years in the early fifth.

Several other vessels represent probable evidence of mid-sixth-century ceramic production. A fully coated Lakonian-style stirrup krater in Knossian fabric with 80 per cent of the rim preserved (Coldstream Reference Coldstream1973, no. L23; Fig. 8) likely dates to the mid-sixth century, between 575 and 525 BCE.Footnote 7 Although Lakonian stirrup kraters are difficult to date with precision, the Well H imitation has a folded rim with a flattened upper lip and slightly concave exterior surface, as well as a short neck that tilts outward very slightly and a handle that joins the rim at a horizontal angle, without slanting downward.Footnote 8 These features make it more typical of Lakonian kraters of the second and third quarters of the sixth century BCE than of kraters of 525–475 BCE, which tend to have taller necks and handles that slant slightly downward from the rim (Stibbe Reference Stibbe1989, 38–41). This locally produced vessel implies the presence of sixth-century Lakonian imports at Knossos, a finding confirmed by both Erickson (Reference Erickson2010, 122–3, no. 329) and more recently Paizi (Reference Paizi2023, 280, no. 22), which would have been used as models. It also provides likely evidence of ceramic production at the site in the sixth century – a labour-intensive industry that is hard to reconcile with destruction and decline.

Fig. 8. Lakonian stirrup krater from Royal Road North, Well H (Coldstream Reference Coldstream1973, 51, no. L23).

Two pyxides with short vertical collared necks (Coldstream Reference Coldstream1973, 51, nos L21–2) resemble a Cretan pyxis from Deposit II at Tocra, dating between 590 and 565 BCE: L21 shares similar banded decoration, with an alternation of thick and thin bands of gloss and a thick stripe of gloss on the top of the handle, while L22 has a carinated shoulder like the Tocra example (Boardman and Hayes Reference Boardman and Hayes1966, 80, no. 926, pl. 56). Pyxides with carinated shoulders, both banded and plain, have also been found in Archaic pithos burials at Tarrha in south-west Crete, where they have been dated to the first half of the sixth century BCE (Tzanakaki Reference Tzanakaki, Niemeier, Pilz and Kaiser2013, 214–15, nos Π2426, Π2429, Π2465, figs 15, 18, 21, 28β, 29γ, 31β); a dipped early sixth-century example from Prinias has the same shape (Pautasso and S. Rizza Reference Pautasso and Rizza2023, 56–7, no. 19, pl. 5).

Finally, many stylistic elements on Well H pottery are familiar from the Well LA assemblages. This is especially true for large coarse vessels, several of which bear ‘Orientalising’ motifs like stamped spirals, rosettes, and even a ‘tree of life’ pattern. Though Coldstream (Reference Coldstream1973, 60, no. L112) presents this latter sherd as a seventh-century intrusion, a similar volute tree motif has been documented on a pithos found in the ‘East Corridor House’ at Azoria (a complex associated with the Communal Dining Building), illustrating the persistence of this design (or the continued use of objects employing this design) in later contexts (Haggis et al. Reference Haggis, Mook, Scarry, Snyder and West2004, 355–6). Concentric painted circles (both light-on-dark and dark-on-light), a common motif on settlement pottery from Knossos through the seventh century, appear on multiple open fineware vessels (Fig. 9). The floral motif combined with concentric circles on the base of one tray or plate is reminiscent of a Cretan plate from Deposit III at Tocra, dated c. 565–510 BCE (Boardman and Hayes Reference Boardman and Hayes1973, 38, no. 2108, pl. 16). A bowl or small lekane (Fig. 10) employs white bars on a red painted rim, a motif found as early as the Geometric period in the Knossian cemeteries (Coldstream Reference Coldstream, Coldstream, Eiring and Forster2001, 59–60).

Fig. 9. Painted decoration on the interior and exterior bases of open vessels from Royal Road North, Well H.

Fig. 10. Bowl or small lekane from Royal Road North, Well H.

Another notable find from Well H is two different palmette antefixes of similar styles (Coldstream Reference Coldstream1973, nos L117 and L118), along with a small fragment of an antefix with a bead-and-reel design, all in the same fabric (Fig. 11). Pieces of Corinthian tile were also observed in the eighth metre of the deposit. Winter (Reference Winter1993, 266) accepts the Late Archaic date for the piece, but also notes similar palmette and double volute combinations in the last quarter of the sixth century. The two pieces are made in a distinctive fabric: coarse with large dark brown inclusions (possibly mudstone) and abundant vegetal temper, covered with a thick cream-coloured slip. This differs from the usual Archaic pithos fabrics at Knossos, suggesting that the pieces may be imported. Indeed, it would be surprising if a Knossian workshop produced elaborate terracottas like this, given Crete's low level of investment in monumental tile-roofed architecture compared to many other regions of the Archaic Greek world.

Fig. 11. (a) L117 (Coldstream Reference Coldstream1973, 60); (b) L118 (Coldstream Reference Coldstream1973, 60); (c) antefix fragment with bead and reel. Antefixes from Royal Road North, Well H.

These objects attest to an architecturally elaborate structure in the late sixth or early fifth century located near the Royal Road North area. Given that no other decorative terracottas were recovered from the fill, and that the large palmette does not seem to have been attached to a cover tile (Winter Reference Winter1993, 266), a temple seems unlikely. The antefixes might have been used instead as anthemia on a grave monument or small funerary building; their closest stylistic parallels are Late Archaic funerary anthemia from Paros and Thera (Buschor Reference Buschor1933, 44, pl. 16:1,2). This structure appears to have been dismantled shortly after its construction and its remains discarded in Well H. If these elements originally belonged to a funerary structure, but were deposited together with abundant domestic pottery, this has interesting implications for the urban topography of Knossos in the Archaic and Early Classical periods. Perhaps the settlement pattern at this time was dispersed, with clusters of habitation separated by small distances, each associated with its own burial ground. I discuss this possibility further below.

The evidence presented here should cause us to re-evaluate the Well H deposit. In the face of such a large quantity of Attic imports, 500 to 480 BCE is a reasonable date for the well's closure. However, that does not mean that every sherd in the well's fill dates to the early fifth century. I see two main possibilities, which are not mutually exclusive. First, it is possible that, although the well was filled in the Late Archaic period, the operation included residual debris from the vicinity that dates to the middle of the sixth century, such as the lamps, the imitation Lakonian krater, and the banded pyxides. Second, it is possible that the material in the deposit mostly dates to between 525 and 480 BCE, but that some trends in material culture remained remarkably conservative, such that Knossian lamps of the Late Archaic period retained shapes reminiscent of Athenian and Corinthian lamps of 75 to 25 years before, and Knossians continued to copy Lakonian kraters of a style most popular in a bygone century. In this case, much locally produced pottery would remain old-fashioned in its appearance, while imported items, such as the Attic ceramics and the palmette antefixes, would follow more up-to-date stylistic trends in the Late Archaic Aegean. Yet even this scenario requires some knowledge of and continuity with previous ceramic styles, further eroding the tenability of a radical break at Knossos in the sixth century. The lack of Attic imports clearly dating to earlier than 525 BCE in this well does not, in my opinion, require a special historical explanation, since Attic imports of the mid-sixth century are rare across Knossos in general.Footnote 9 While the rich late sixth- to early fifth-century Attic sympotic assemblage in Well H is certainly striking, it is a unique assemblage at the site and need not represent the practices of more than one, perhaps an unusual, Knossian household.Footnote 10

WELLS FROM THE UNEXPLORED MANSION EXCAVATIONS

The Unexplored Mansion excavations, located several hundred metres north-west of the Royal Road excavations, were carried out in the vicinity of a large Minoan building first exposed by Arthur Evans. Work at the Unexplored Mansion in the 1960s and 1970s also yielded substantial post-Minoan deposits (primarily Hellenistic and Roman), creating an extremely complex stratigraphy. Few architectural features or occupation surfaces could be dated to the seventh through fifth centuries BCE besides a scrap of clay floor, part of a built hearth, and a few fragmentary terrace or building walls; Protoarchaic through Early Classical material comes almost exclusively from pit and well fills (Sackett and Jones Reference Sackett and Jones1992, 5–8). The 1973 season was spent excavating post-Minoan wells, including the two discussed below – Well 12 and Well 8a – both of which have a conventional dating that comes close to the boundaries of the Knossian gap. The two wells were located roughly 13 metres apart: Well 8a had been dug along the west edge of the Minoan building, clipping its outer wall, while Well 12 was located to its south-east, sealed below a Hellenistic cistern sunk through the Minoan building's floor (Fig. 12).

Fig. 12. Location of Wells 12 and 8a within the Unexplored Mansion excavations. After Sackett Reference Sackett1992, pl. 5. Reproduced with the permission of the British School at Athens.

Well 12

Well 12 was initially dated to the very end of the seventh century based on one imported Corinthian oinochoe from the upper fill (of which only the base was preserved), as well as ‘Corinthianising’ oinochoes, including one with incised shoulder petals and painted rays, in the primary deposit (Coldstream and Sackett Reference Coldstream and Sackett1978, 56–60, nos 7 and 52, figs 6 and 10). The surface associated with the well was not preserved, as the upper part had been truncated by a Hellenistic cistern filled with Hadrianic pottery. The fill was excavated to its bottom at 14.4 metres, but the excavators estimated the original depth at 23.7 metres (accounting for the cistern and Minoan debris above). This is exceptionally deep, both compared to other wells at Knossos and to contemporary examples from Athens: 72 Protoattic and Archaic wells from the Athenian Agora have an average depth of 8.3 metres, and none exceed 17 metres (Camp Reference Camp1977, 195–207). Footholds had been carved into the well's side to facilitate access. No water was encountered at the well's bottom, suggesting that the water table had moved since antiquity (British School at Athens Archives, Knossos Excavation Records, KNO1006, 111). The well's upper fill (levels 68–82) was largely homogeneous and contained rubble mixed with clayey soil, bone, and varying amounts of ceramics, including many sherds of large coarse storage vessels; several worked stones and a millstone fragment were recovered from levels 76 through 79 (KNO1006, 105; Coldstream and Sackett Reference Coldstream and Sackett1978, 58). The primary well deposit (level 83) consisted of 13 intact or nearly intact vessels, 15 vessels that could be partially restored, and several concentrations of pithos fragments, including some with impressed spirals (KNO1006, 109; KNO1025, 39–40).

The same caveats discussed above with respect to the Royal Road wells apply here too: a single Corinthian sherd, especially a relatively undiagnostic oinochoe base,Footnote 11 is not a strong foundation upon which to date the entire deposit. Even if the vessel could be dated with certainty to the late seventh century, we could not rule out the possibility that it was retained into the sixth century. A slowdown in Corinthian imports at 600 BCE would not necessarily indicate a cessation of all activity in this area or across Knossos in general. Other pottery from Well 12 suggests that some material dates to later than 600 BCE. The upper fill yielded sevenFootnote 12 cup bases with the stepped profile underfoot and splayed foot characteristic of the sixth century and found also in Royal Road Well LA (Figs 13 and 14). Two other closed vessels of different sizes, possibly a small jug and a hydria, have a similar foot and are likely contemporary with these cups (Fig. 15); they find good parallels among hydrias and jugs from Kommos (Johnston Reference Johnston1993, 345–7, nos 19 and 29, fig. 3F,G; Callaghan and Johnston Reference Callaghan, Johnston, Shaw and Shaw2000, 247, no. 371, pl. 4:17) and, as discussed in more detail above, could date to the mid-sixth century BCE.

Fig. 13. Cups and small jug with stepped profile underfoot from upper fill of Unexplored Mansion Well 12.

Fig. 14. Cups with stepped profile underfoot from upper fill of Unexplored Mansion Well 12.

Fig. 15. Closed vessels with stepped profile underfoot from upper fill of Unexplored Mansion Well 12.

Several small shapes from the upper fill are noteworthy for their decoration. The first type, preserved in several examples, is a kotyle or cup with fine line banding on the exterior of the base (Fig. 16). While the decorative banding would not be out of place in the late seventh century, the cup's combination of a low, fairly vertical ring foot with a thick floor looks later. Similar cups found at Praisos have been dated to between 575 and 525 BCE (Erickson Reference Erickson2010, 208–10, nos 482–3 and 485, fig. 8:7), though most of these examples are fully coated on the exterior. The second, a small domed lid, perhaps to a pyxis (Fig. 17), combines fine line banding with a dot pattern similar to the stylised ivy of sixth-century Attic black figure.Footnote 13

Fig. 16. Kotyle or cup from upper fill of Unexplored Mansion Well 12.

Fig. 17. Small lid from upper fill of Unexplored Mansion Well 12.

Among larger vessels from the upper fill, two large lekanes with wide projecting rims, bands of red or brown paint, and a slight carination below the rim (Fig. 18) combine characteristics of both seventh-century and early fifth-century Knossian lekanes – the ridge on the shoulder is similar to Orientalising lekanes from the Southwest Houses (Coldstream and Macdonald Reference Coldstream and Macdonald1997, 217–20, nos G40, G42, H18, H19), while the slightly overhanging rim with paint appears on a lekane from a Late Archaic pit fill, Deposit K, in the same area (Coldstream and Macdonald Reference Coldstream and Macdonald1997, 224, no. K34). A Well 12 pyxis with a squared rim and a red band extending to inside the rim (Fig. 19) also recalls examples from Deposit K (Coldstream and MacDonald Reference Coldstream and Macdonald1997, no. K22). It is worth noting that Deposit K was dated to the Late Archaic period based on comparison with Well H, but like Well H includes many shapes consistent with a sixth-century date, including cups with stepped profile underfoot and a local imitation of a black coated stirrup krater (Coldstream and Macdonald Reference Coldstream and Macdonald1997, 224, 242).

Fig. 18. Lekanes from upper fill of Unexplored Mansion Well 12.

Fig. 19. Pyxis from upper fill of Unexplored Mansion Well 12.

In Well 12, as in Wells LA and H from the Royal Road, the use of light-on-dark and dark-on-light banding is popular and appears on a variety of open and closed vessels in both fine and medium coarse fabrics. Pithoi from Well 12 employ the same two fabrics as those recovered from the two Royal Road Wells. The decorative motifs on the pithoi are also similar and include examples with stamped circles, stamped concentric circles, incised herringbone, running spirals traced with a finger or other object, and slashed raised bands (Fig. 20). If the conventional dates for these three deposits are correct, it suggests strong continuity of tradition in shapes, decoration, and fabrics from the late seventh century (Well LA, Well 12) to the early fifth century (Well H), across the span of the purported gap, which even in its shortest proposed iteration would have spanned multiple generations. While the sampling methods used during the Knossos excavations are not conducive to rigorous quantitative analysis, the substantial amount of these pithoi present in Well H makes it difficult to explain them away as a smattering of seventh-century material caught up in the fill. Rather, it seems more likely either that production of pithoi at Knossos continued through the sixth century or that these objects are late seventh-century products that were curated across the sixth century; either scenario implies some continuity of occupation at the site.

Fig. 20. Decorated pithos sherds from upper fill of Unexplored Mansion Well 12.

My discussion so far has focused mostly on finewares, partly due to the higher diagnosticity of many fineware shapes and partly from necessity, as coarsewares tended to be discarded by mid-twentieth-century excavators at Knossos. In a happy departure from this trend, the entirety of the primary deposit of Well 12 (level 83) appears to have been kept, including coarseware and undecorated body sherds. Two major fabrics are represented in the primary deposit: a coarse, reddish-brown fabric with white, grey, and silver mica inclusions (519 sherds, 9.80 kg), and the typical local pink fineware with rare white or grey inclusions (225 sherds, 3.75 kg). The coarseware appears to have been used as a cooking fabric – a cooking jug with grooves on the neck, partially burned, survives almost in its entirety. Hydriai and trefoil oinochoai are made in both fabrics. These domestic vessels do not change much between deposits dated to the late seventh and to the early fifth centuries at Knossos, and some of them could date to the sixth century; in fact, one fineware hydria from the primary deposit has the stepped profile underfoot found on sixth-century cups and closed vessels from the upper fill (Fig. 21). The large number and variety of vessels in the well's primary deposit may indicate that Well 12 was used by a larger group of people than a single family, an interpretation that accords well with the substantial amount of labour that would have been required to construct this remarkably deep well.

Fig. 21. Hydria from primary deposit of Well 12.

Well 8a

As for Unexplored Mansion Well 8a, Coldstream himself nominated Deposit GG in the upper fill as the most likely candidate to fill his sixth-century gap, though he believed the bulk of the deposit to be late seventh century in date (Coldstream Reference Coldstream1992, 85–6). Erickson dates two cup bases with flaring pedestal feet from the deposit to 590 BCE and calls the deposit the ‘only unambiguous trace of domestic activity’ from sixth-century Knossos (Erickson Reference Erickson2010, 124, 236, nos 245–6). I was unable to access any unpublished material from this deposit but can provide a few brief notes. Pithoi in Well 8a are made from the same pinkish fabric with vegetal temper observed in the Royal Road North Wells and in Well 12 and often bear similar stamped decoration, further highlighting the ubiquity of these vessels across the settlement and the possible continuity of craft production traditions between the Protoarchaic and Late Archaic periods at Knossos. The deposit contained no recognisable imports, but it did include a local imitation of a fully coated Lakonian stirrup krater (Coldstream Reference Coldstream1992, 75, no. GG7, pl. 57). While this krater is more fragmentary than the example from Well H and therefore more difficult to date, the rim shape, which is concave on the outside and slightly overhanging, resembles Lakonian examples that date between 575 and 550 BCE (Stibbe Reference Stibbe1989, nos F24 and F31, figs 57 and 64). Coldstream (Reference Coldstream1992, 85) also notes lekanes with folded rims that depart from the seventh-century norm at Knossos, as well as a lamp that could also be from the sixth century (Coldstream Reference Coldstream1992, 75, no. GG17, pl. 57). Though not the same form as the lamps in Royal Road Well H, it is closest to Agora Type 5, dated between the second and the fourth quarters of the sixth century BCE (Howland Reference Howland1958, 14–15, nos 30 and 32, pl. 2), or Corinth Type 1, dating to the first half of the sixth century (Broneer Reference Broneer1930, 31–3, no. 10, fig. 14). The presence in the Well 8a fill of fineware with painted concentric circles again emphasises the continuity of these decorative motifs into the sixth century at Knossos.

CONCLUSIONS

Several factors have contributed to the perception of a sixth-century gap in occupation at Knossos. The first of these is a relatively low number of sixth-century imports. Corinthian, Attic, and to a lesser extent Lakonian imports and imitations provide critical chronological anchors for regional pottery sequences. The sixth century marks an important transition for this method of relative dating, as Corinthian exports waned across much of the Greek world, starting in the second quarter of the sixth century, including at Eleutherna, where Lakonian and later Attic imports dominate after 575 BCE (Salmon Reference Salmon1984, 109–11; Erickson Reference Erickson2010, 51–6, 273–4). If the population at Knossos was relatively quick to abandon Corinthian imports, ceasing in the late seventh century, and relatively slow to adopt Attic ones, beginning in earnest in the Late Archaic (as represented by the rich assemblage of Attic imports in Well H), it would lead to a pattern like what has been observed in these wells.

A paucity of sixth-century imports at Knossos does not necessarily imply military catastrophe or dramatic depopulation. As discussed above, imports continued to reach Knossos in a slow trickle across the sixth century (Paizi Reference Paizi2023). The presence of local pottery inspired by foreign shapes provides further indirect evidence for imports at this time. This includes three imitations of mid-sixth-century Lakonian stirrup kraters, like those found in Royal Road Well H, Unexplored Mansion Well 8a, and Southwest Houses Deposit K, and a lid resembling sixth-century Attic black figure from Well 12. Imports are not wholly absent at Knossos, but their relative scarcity makes it difficult to use them consistently as a dating method.

Related to this issue is a lack of abundant comparanda for sixth-century ceramics, not only in Crete, but across the Greek world in general. Neither Azoria nor Prinias, our two most important known sites with stratified Cretan contexts dating to the sixth century, have yet been fully published, making sixth-century Cretan pottery difficult to recognise. There are few well-published sixth-century domestic assemblages outside of Crete either, and the coarseware and cooking vessels that likely composed a large proportion of many household assemblages are especially poorly represented. Even in the Athenian Agora, evidence for black-gloss and plain wares is relatively sparse until the end of the sixth century, with very little published from before 550 BCE and much material concentrated in the Late Archaic period, around the time of the Persian destruction (Sparkes and Talcott Reference Sparkes and Talcott1970, 12–13). Given this state of affairs, the shunting of so much Knossian material into the period between 500 and 480 BCE should perhaps give us pause, especially for regions like Crete which are largely peripheral to the mainstream (i.e. Athenocentric) narrative of Greek history. Archaeologists flock to chronological fixed points as moths around a candle, and understandably so – we need these points of light to organise the masses of material culture that confront us. But it remains vitally important for us not to confuse these bright spots in our historical chronologies with actual clusters in our data, especially when drawing links between disparate parts of the Greek world.

Another factor contributing to the apparent Knossian gap is the strong likelihood, based on my observations of these deposits and information from other excavated Cretan sites such as Azoria, that styles habitually assigned to the seventh century on Crete often persisted into the sixth century or even the early fifth century. In these Knossian well deposits, such conservative styles include fineware with concentric circle designs in light-on-dark and dark-on-light patterns, as well as pithoi with a large variety of stamped decoration. We see these traditions continue between deposits assigned to the late seventh century (Well LA, Well 12) and the early fifth century (Well H). This conservatism is visible at other sites in Crete, and particularly at Azoria, where Daedalic figurines and relief pithoi with ‘Orientalising’ decoration have been found in multiple sixth- and early fifth-century use-contexts (Haggis et al. Reference Haggis, Mook, Scarry, Snyder and West2004, 355; Reference Haggis, Mook, Fitzsimons, Scarry and Snyder2011a, 34–7; Reference Haggis, Mook, Fitzsimons, Scarry and Snyder2011b, 468–9). There are two possible ways to interpret this phenomenon: either these objects were originally manufactured in the seventh century and were subsequently used for multiple generations, or they were manufactured continually in the same or very similar styles from the seventh century into the sixth and beyond. Both figurines and relief pithoi have distinctive manufacturing processes, often requiring moulds or stamps which can be used multiple times, and perhaps lend themselves more easily to persistent craft traditions. In any case, the evidence is clear enough to demonstrate that we cannot use these objects as unambiguous type fossils for the seventh century.

This should also cause us to reconsider the dating of the figurines from the Sanctuary of Demeter at Knossos. Here, Daedalic plaques and protomes were dated to the seventh or the early sixth century on stylistic grounds, while the sixth century was characterised as figurine-poor (Higgins Reference Higgins and Coldstream1973, 58, nos 6–10, pl. 33, 182). Given the Azoria evidence, we should entertain the possibility that some of these Daedalic figurines either remained in use from the seventh century into the sixth or continued to be produced in the sixth century; the stylistic dating cannot be relied upon to confirm a seventh-century date. Only one published terracotta at the Demeter Sanctuary was attributed definitively to the mid-sixth century: a moldmade figurine of a standing woman with arms at her sides (Higgins Reference Higgins and Coldstream1973, 59, no. 11, pl. 33). Though it has been suggested that this figurine was produced after 525 BCE from a mold based off a Sicilian import (Erickson Reference Erickson2014, 81–2), we in fact need not look so far afield for a workable parallel. Female figurines in this pose have been recovered from the sanctuary at Gerakaro at ancient Oaxos, where they are referred to as ‘Type A’ figurines and dated across the span of the sixth century (Tegou Reference Tegou, Gavrilaki and Tzifopoulos2006, 278–9, figs 4–5; Reference Tegou2014, 58, fig. 10).

Such ‘conservatism’ is a different phenomenon from the ‘austerity’ often invoked to describe Cretan material culture of the sixth century. The term ‘austerity’ invites comparisons to literary depictions of Archaic and Classical Sparta, where material displays of wealth were allegedly aggressively eschewed (though perhaps more in theory than in practice; see Hodkinson Reference Hodkinson2000 and van Wees Reference Wees and Powell2018). In the context of Archaic Cretan archaeology, ‘austerity’ has been used to describe the lack of easily archaeologically visible sixth-century burials, changing cult practices at some urban and suburban sanctuaries emphasising the dedication of modest terracotta votives, and a preference for plain tablewares over elaborate figured wares (Whitley Reference Whitley, Cadogan, Hatzaki and Vasilakis2004, 438–41; Erickson Reference Erickson2010, 309–45; Brisart Reference Brisart2014; Seelentag Reference Seelentag2015, 22; Gagarin and Perlman Reference Gagarin and Perlman2016, 29–36; Erickson Reference Erickson2023, 498–503). It has been argued, most forcefully by Erickson (Reference Erickson2010; Reference Erickson2023), that an austere ceramic material culture of fully coated high-necked drinking cups of standardised size, deployed in the context of communal dining, helped to create cohesion and suppress competition between citizens of Cretan poleis, overtly reinforcing an ideology of political equality. Cretan austerity is often presented as an exceptional feature of the island, but similar models have been proposed for much of the Archaic Greek world, from I. Morris’ (Reference Morris1992, 145–55) arguments about cycles of display and restraint across the first millennium BCE Aegean to Seelentag's (Reference Seelentag, Meiser and Seelentag2020) more recent concept of ‘cartelisation’, in which Archaic Greek elites forfeited the right to compete with each other in the service of a shared goal, such as defeating external enemies or maintaining control over those of lower social status.

Though such models may help to explain some aspects of the Archaic ceramic record, such as the rejection of black-figure vessels, the concept of austerity does not sufficiently address all features of central Cretan material culture in the sixth century. Elaborate relief pithoi, Daedalic figurines, and finewares with painted decoration cannot accurately be described as ‘austere’. Augmenting the concept of ‘austerity’ with that of conservatism, or persistence of select material culture traditions from earlier centuries, allows for new possible interpretations of the Cretan evidence. We might read these two trends in competition, with some potters and painters continuing to pursue select Protoarchaic traditions and others embracing a plain, monochrome ceramic repertoire. Alternatively, austerity and conservatism might both represent responses to the new Cretan civic cultures developing at the juncture of the Protoarchaic and Archaic periods – perhaps conservative styles were appropriate for certain contexts within the new political and social order, but not others. Some types of ceramics can fairly be characterised as both austere and conservative, such as the monochrome coated cups with a single vertical handle produced from the Geometric period through the Classical period at Knossos and many other Cretan sites (Erickson Reference Erickson2023). In all these framings, however, austerity and conservatism are recast as conscious cultural choices rather than as evidence for ignorance of wider Aegean trends, demographic crisis, or economic collapse.

These issues pose substantial questions that will require further work to resolve completely. However, this does not leave us entirely at a loss when it comes to identifying sixth-century ceramics at Knossos. Though refinements of sixth-century Cretan chronologies will require further excavation, this study of legacy material at Knossos points to some features that are potentially diagnostic of the sixth century: a stepped profile underfoot on cups and on some closed pouring vessels like jugs and hydria, lekanes with folded rims, baggy-sided lamps with large fill-holes, local imitations of fully coated Lakonian stirrup kraters, and banding on large fineware vessels like lekanes and pyxides. Vessels with sixth-century shapes but ‘old fashioned’ decoration, such as cups with ring bases or the combination of splayed foot and stepped profile foot that are decorated with light-on-dark paint or banding, may also be indicative of sixth-century production. Erickson (Reference Erickson2010, 25, table 2:1) notes that banded wares are relatively rare in deposits dated to the Late Archaic and Classical periods at Knossos when compared to plain black gloss (at least among retained pottery). In Athens, banding is relatively more prevalent in the sixth century than in the fifth, when fully coated vessels are more popular (Sparkes and Talcott Reference Sparkes and Talcott1970, 18). More relevant are the deposits of central Cretan pottery from Tocra mentioned above, which belong to the middle of the sixth century and employ similar banding on lekanes, hydriai, pyxides and trays.

My reinterpretation of these excavated well deposits aligns well with new findings from the Knossos Urban Landscape Project, or KULP, an intensive diachronic urban survey of Knossos, and from other new studies of excavated material. Preliminary analyses of the surface material collected by KULP have identified sixth-century pottery across the 11 square kilometre survey area, including kraters, lekanes, bowls, and lamps, as well as some Corinthian, Lakonian, and Attic imports (Trainor Reference Trainor2019, 4–5). The distribution of this material suggests that sixth-century Knossos, far from experiencing a sharp contraction towards the end of the seventh century, was about the same size as Early Iron Age and Protoarchaic Knossos, though not as large as the Classical and Hellenistic town. Low-density, dispersed distributions of Archaic survey pottery are characteristic of other Greek regions as well, so this is not just a Knossian or Cretan phenomenon. Archaeologists working in the Eastern Corinthia have argued that low-signature periods like the Archaic are likely to be missed by site-based survey methods, such as those most often used in Crete (Caraher, Nakassis and Pettegrew Reference Caraher, Nakassis and Pettegrew2006, 18–21). It may be that more intensive methods like those used by KULP are needed to observe the subtle hints of sixth-century occupation on Knossos and across Crete in general.

We also may need to adjust how we conceive of the spatial organisation of the Cretan polis at this critical juncture between the seventh and the sixth centuries BCE. Rather than being a densely nucleated centre, it is possible that the Knossian polis was arranged kata komas, with small clusters of settlement separated by tracts of open land. A more dispersed pattern of settlement would fit well with KULP's description of low densities of sixth-century pottery spanning an area similar in size to the Early Iron Age settlement. A similar arrangement has been proposed for Gortyn in the sixth and fifth centuries as one way to explain the low visibility of the Archaic and Classical city there (Anzalone Reference Anzalone2015, 147–8). Gortyn is a productive comparison for Knossos in several ways. Both sites witnessed significant Hellenistic, Roman, and later occupation, often in areas that greatly disturbed Archaic and Classical deposits. Imported pottery of the mid-sixth century is rare at both sites, with the exception of an Attic black-figure dinos and Little Master cup at the Gortynian cult site on Agios Ioannis, dating between 570 and 525 BCE (Johannowsky Reference Johannowsky2002, 107, nos 639–40, pl. 50). The evidence for local pottery production is also thin in the mid-sixth century. Little published material dates to the decades between a late seventh and early sixth-century deposit with much production debris (Santaniello Reference Santaniello2004) and the late sixth-century material from both the Sanctuary of Demeter and Kore (Allegro et al. Reference Allegro, Cosentino, Leggio, Masala, Svanera and di Stefano2008) and the pits in the area of the Odeion.Footnote 14 If Gortyn did not have the abundance of legal inscriptions that it does, archaeologists might mistakenly believe there to be an ‘Archaic gap’ there as well. If Archaic Knossos was similarly dispersed and discontinuous, this may account in part for the difficulty of locating the archaeological remains of the settlement (in addition, of course, to substantial overbuilding in the Hellenistic and Roman periods), and it might also help to explain why the Royal Road wells discussed above appear to be located outside houses, in ‘open country’.

The very existence of substantial wells at Knossos further undermines the idea of a gap. Knossos is the only Cretan site where Protoarchaic and Early Classical wells have been securely documented; the Archaic communities at Azoria and Prinias likely relied on local springs for their water.Footnote 15 The Knossos valley did not lack abundant local springs and spring-fed rivers (Hood and Smyth Reference Hood and Smyth1981, 5), but the number of wells at Knossos, including unusually deep wells like Unexplored Mansion Well 12, suggests that the community was willing to invest considerable energy in securing water and perhaps had substantial needs.

The hypothesis of an abandonment or deep recession at Knossos between 590 and 525 BCE based only on an apparent absence of evidence is not, as I have tried to argue, epistemologically defensible. I suggest instead that the apparent sixth-century ‘gap’ at Knossos most likely results from several different factors that make the sixth century difficult to observe archaeologically. These include: a low number of sixth-century imports, lack of appropriate comparanda from well-stratified and fully published Cretan contexts, a dispersed settlement pattern that has made it difficult to locate sixth-century residences and burials, a stylistic conservatism that saw some seventh-century decorative motifs continue into the sixth century, the retention of artefacts like relief pithoi for long spans of time, and the use of plain and banded pottery rather than the evolution of elaborate and chronologically diagnostic local black-figure traditions like those of Corinth or Athens. Even if we can no longer defend the mid-sixth-century ‘gap’, these developments are culturally significant and deserve study. Questioning the ‘gap’ thus opens up new avenues of research, inviting us to consider the factors that drove the marked changes in settlement organisation, consumption of ceramic imports, and local pottery production at Knossos in the sixth century.

Unfortunately, the narrative of the Knossian gap has rippled outward, affecting our interpretation of many other Cretan contexts, including the dating of artefacts found on surface survey and therefore our impressions of population trends and settlement patterns across the island. Correcting these impressions, as well as answering the question of what sixth-century material culture and assemblages look like at Knossos and on Crete more broadly, will require three things, many of which are already in progress: (1) new excavations of stratified contexts on the island; (2) full publication of previously excavated contexts, including coarse and cooking shape and fabric studies, which will allow for a better understanding of regional ceramic chronologies; and (3) re-evaluation of existing narratives through the study of legacy data, as I have done here. Only by exploring all these avenues can we develop a more detailed and comprehensive understanding of the use of material culture in Archaic Cretan society.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I thank Todd Whitelaw for first proposing this project during the Knossos Pottery Course in 2019. Both Todd and Kostis Christakis provided invaluable help at the Stratigraphical Museum at Knossos. Amalia Kakissis assisted with permits and facilitated my study of the Knossos Excavation Archive. Phil Sapirstein provided helpful comments and bibliographic suggestions on the palmette antefixes from Well H, while Tamara Saggini generously allowed me to consult her unpublished thesis on Archaic and Classical pottery from Eretria. The Stanford School of Humanities and Sciences and the Loeb Classical Library Foundation funded my travel to Knossos to pursue this study. Melanie Godsey, Donald Haggis, Jesse Obert and Nick Romeo read various drafts of this paper and improved it immensely. Valia Tsikritea assisted with the translation of the title and abstract into Greek. Finally, I am grateful to two anonymous reviewers who provided extremely critical but galvanising feedback, as well as to Peter Liddel for his editorial guidance.