Published online by Cambridge University Press: 27 September 2013

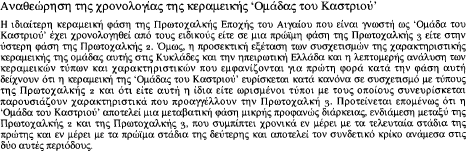

The single ceramic phase of the Aegean Early Bronze Age known as the ‘Kastri group’ has been dated by scholars either to an early phase of EB 3 or to the late phase of EB 2. However, careful examination of the contextual associations of the characteristic pottery of this group in the Cycladic islands and the mainland, and detailed analysis of the ceramic forms and features first appearing in this phase, show the ‘Kastri group’ pottery to occur, as a rule, with forms of EB 2. It is also shown that either this pottery itself, or certain forms with which it occurs, present features heralding EB 3. It is thus proposed that the ‘Kastri group’ constitutes a transitional phase of apparently short duration, intermediate between EB 2 and 3, overlapping in date with both the last stages of the former and the early stages of the latter and ‘bridging’ these two periods.

I would like to thank Professor C. Doumas and lecturer Dr E. Mantzourani for reading my manuscript and making encouraging comments on it. I would also like to thank the UK Editor, Dr D. G. J. Shipley, for his kind invitation to publish this article in the Annual, and both him and the anonymous reader for useful suggestions with regard to its presentation. Special abbreviations:

EB Early Bronze

EBA Early Bronze Age

MBA Middle Bronze Age

EC Early Cycladic

EH Early Helladic

MC Middle Cycladic

NM National Museum (Athens)

Art and Culture = J. Thimme and P. Getz-Preziosi (eds), Art and Culture of the Cyclades (Karlsruhe, 1977)

Barber, Cyclades = R. L. N. Barber, The Cyclades in the Bronze Age (London, 1987)

Doumas, Burial Habits = C. Doumas, Early Bronze Age Burial Habits in the Cyclades (SIMA 48; 1977)

Doumas, Christiana = C. Doumas, ‘Πρωτοκνκλαδικὴ κεραμεικὴ ὰπὸ τὰ Χριστιανὰ Θήρας’, Arch. Eph. 1976, 1–11

‘EC Period’ = R. L. N. Barber and J. A. MacGillivray, ‘The Early Cycladic period: matters of definition and terminology’, AJA 84 (1980), 141–57

Emergence = C. Renfrew, The Emergence of Civilisation: The Cyclades and the Aegean in the Third Millennium BC (London, 1972)

Keos ii = J. L. Caskey, ‘Investigations in Keos, part II: a conspectus of the pottery’, Hesp. 41 (1972), 357–401

MacGillivray, Kynthos = J. A. MacGillivray, ‘Mount Kynthos in Delos: the Early Cycladic settlement’, BCH 104 (1980), 3–45

PC = J. A. MacGillivray and R. L. N. Barber (eds), The Prehistoric Cyclades: Contributions to a Workshop on Cycladic Chronology (Edinburgh, 1984)

Phylakopi = T. D. Atkinson et al., Excavations at Phylakopi in Melos (JHS suppl. paper 4; 1904)

Problems = E. B. French and K. A. Wardle (eds), Problems in Greek Prehistory: Papers Presented at the Centenary Conference of the British School of Archaeology at Athens (Manchester, Apr. 1986) (Bristol, 1988)

Rutter, Change = J. B. Rutter, Ceramic Change in the Aegean Early Bronze Age: The Kastri Group, Lefkandi I and Lerna IV: A Theory concerning the Origin of Early Helladic III Ceramics (University of California Institute of Archaeology, Occasional Paper 5; Los Angeles, 1979)

2 Emergence, 533–4.

3 For the pottery forms considered to be characteristic of the ‘Kastri group’, see Emergence, 533–4, fig. 11. 2, pl. 9. 1–4; Doumas, Christiana, 8 n. 2; id., Burial Habits, 22–3, fig. 11; id., Cycladic Art: Ancient Sculpture and Pottery from the N. P. Goulandris Collection (London, 1983), 44; id., Problems, 23; Rutter, , Change, 6, 20 n. 5, 21 n. 11, figs. 1–2Google Scholar; ‘EC Period’, 151, ill. 2. 18–22; Barber, Cyclades, 93–4, fig. 58. 18–22.

4 Emergence, 103, 533.

5 Rutter, Change, 20–1 n. 5.

6 Art and Culture, 112–13, 535–6, pls. 417–18.

7 Bossert, E.-M., ‘Kastri auf Syros’, A. Delt. 22 (1967), Mel. 70–3Google Scholar; Popham, M. R. and Sackett, L. H., Excavations at Lefkandi, Euboea, 1964–66 (1968), 8 Google Scholar; Caskey, J. L., ‘The Early Bronze Age at Ayia Irini in Keos’, Archaeology, 23 (1970), 342 Google Scholar; id., ‘Notes on Keos and Tzia’, Hesp. 50 (1981), 322; Emergence, 533–4; Doumas, Burial Habits, 22; Rutter, Change, 6–8; id., ‘Fine gray-burnished pottery of the Early Helladic III period: the ancestry of Gray Minyan’, Hesp. 52 (1983), 344–5, 347. ‘EC Period’, 155; MacGillivray, Kynthos, 25; id., PC 70; Barber, ibid. 88; id., Cyclades, 29, 94, 138; Gale and Stos-Gale, PC 268; Sampson, A., Μάνικα· μια πρωτοελλαδική πόλη στη Χαλκίδα , i (Etaireia Euboikon Spoudon, Tmima Chalkidas, 1985), 255, 258Google Scholar; Mellink, M., ‘The Early Bronze Age in West Anatolia’, in Cadogan, G. (ed.), The End of the Early Bronze Age in the Aegean (Cincinnati Classical Studies, n.s. 6; Leiden, 1986), 148–51.Google Scholar

8 Doumas, Problems, 23.

9 Bossert (n. 7), 72, n. 58; Rutter, , Change, 4, 8, 12, 21 n. 6Google Scholar; MacGillivray, Kynthos, 25; ‘EC Period’, 151; Barber, Cyclades, 94.

10 Doumas, Problems, 23.

11 Rutter, J. B., ‘An exercise in form vs. function: the significance of the duck vase’, Temple University Aegean Symposium, 10 (1985), 18.Google Scholar

12 Rubensohn, O., ‘Die prähistorischen und frühgeschichtlichen Funde auf dem Buärghügel von Paros’, AM 42 (1917), 44, Abb. 45Google Scholar; Barber, R. L. N., ‘The Cyclades in the Middle Bronze Age’, in Doumas, C. (ed.), Thera and the Aegean World: Papers Presented at the Second International Scientific Congress, Santorini, Greece (Aug. 1978), i (London, 1978), 368 Google Scholar; ‘EC Period’, 150 n. 69.

13 Evans and Renfrew, PC 67.

14 Sotirakopoulou, P., ‘Οι πρωιμότατες φάσεις του Ακρωτηρίου· νεολιθική καὶ πρωιμη εποχή του χαλκου’, Ακρωτήρι Θήρας· είκοσι χρόνια έρευνας (1967–1987). Ημερίδα (Αθήναι, 19 Δεκ. 1987) (Athens, 1992), 191 Google Scholar; ead., ‘The earliest history of Akrotiri: the late neolithic and early bronze age phases’, in Hardy, D. A. and Renfrew, A. C. (eds), Thera and the Aegean World III: Proceedings of the Third International Congress, Santorini, Greece (3– 9 Sept. 1989), iii (London, 1990), 43 Google Scholar; ead., Ακρωτήρι Θήρας· η νεολιθική και η πρώιμη εποχή του χαλκού επί πη βάσει πης κεραμεικής(unpublished doctoral thesis, University of Athens, 1991).

15 See Emergence, 453, fig. 20. 5, and Renfrew, C., Problems in European Prehistory (Edinburgh, 1979), 128, pl. 12Google Scholar, for the distribution of two of the type shapes of the ‘Kastri group’, namely the one-handled tankard and the depas.

16 Emergence, 172, 533–4, fig. 11. 2; Doumas, , Burial Habits, 15, 25.Google Scholar

17 Keos ii. 370.

18 Caskey, Hesp. 50 (n. 7), 321–2.

19 Mellink (n. 7), 149, pl. 16 at p. 144.

20 Barber (n. 12), 368.

21 ‘EC Period’, 150, 151, table 1.

22 PC, chronological chart at p. 301. MacGillivray, , Kynthos, 25, 45 Google Scholar; id., PC 70, 75; Barber, R. L. N., ‘The definition of the Middle Cycladic period’, AJA 87 (1983), 80, 81CrossRefGoogle Scholar; id., PC 88; id., Cyclades, 28, 93–4, 141, 249 n. 12, figs. 22–23.

23 Doumas, Problems, 28.

24 Sotirakopoulou, P., ‘Early Cycladic pottery from Akrotiri on Thera and its chronological implications’, BSA 81 (1986), 309–10Google Scholar; ead.,Ημερίδα (n. 14), 191; ead., Thera and the Aegean World III (n. 14), 43.

25 Rutter, Change, 6.

27 Sampson (n. 7), 149.

28 ‘EC Period’, 155; Barber, , AJA 87 (n. 22), 79–81, addendumGoogle Scholar; id., PC 88–94; id., Cyclades, 139; MacGillivray, J. A., ‘On the relative chronologies of Early Cycladic III A and Early Helladic III’, AJA 87 (1983), 81–3CrossRefGoogle Scholar; id., PC 70–7; Sotirakopoulou, , BSA 81 (n. 24), 309 Google Scholar; Doumas, Problems, 21–9.

29 See n. 16.

30 Caskey, J. L., ‘Investigations in Keos, part I: excavations and explorations, 1966–70’, Hesp. 40 (1971), 371–2, 384.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

31 Keos ii. 362.

32 Ibid. 370.

33 Sotirakopoulou, doctoral thesis (n. 14).

34 Information kindly given to me by Dr David Wilson in personal communication in 1985. For the bell-shaped cups and the plates or shallow bowls see also Wilson and Eliot, PC 83, fig. 4: ‘The end of the first phase [period II] of House E is marked by a hard, red debris layer over the upper clay floor of Rooms 1 and 2 [of period II]. Found in this debris level were a range of wares not dissimilar from the Period II floor deposits below; however, for the first time, fragments of red and black burnished ware including bell–shaped cups and red/brown burnished shallow bowls [i.e. Keos ii, fig. 6. c 35; pl. 81, c 33] are found. This debris level marks a time of reorganisation in the area during the building of Rooms 3 to 7 [of period III] … In effect, what we have is the construction of a new building using the same alignment as the first phase of House E, the same construction techniques and style of masonry, and reusing several walls at the same time as Period III ceramic features were first appearing’. For the initial appearance at Ayia Irini of the ‘Kastri group’ pottery together with EC II forms see also Barber, Cyclades, 138.

35 MacGillivray, PC 75; Mellink (n. 7), 147,148.

36 MacGillivray, PC 74.

37 Wilson, and Eliot, , PC 85, 87 n. 6, fig. 4Google Scholar: ‘(period III) Rooms 4, 5 and 6 were filled with red debris and stone, perhaps to be equated with the disintegration of mudbrick walls and a general collapse of the upper storey. A similar debris level stretched over the possible yard level above the earlier Room 2 to the west. From the fill of these rooms came tankards; depa (i.e. Keos ii. c 47–8, fig. 7, pl. 80); burnished shallow bowls …’

38 Keos ii. 366, B 41; 372, c 14–16; figs. 3, B 41; 7, c 14–16.

39 Ibid. 366. B 41; 372, c 14–17; figs. 3, B 41; 7, c 14–17; pl. 78, B 41; Rutter, , Change, 4, 20 n. 4Google Scholar; ‘EC Period’, 151; Wilson, and Eliot, , PC 81, 87 n. 2.Google Scholar

40 Personal communication with Dr D. Wilson.

41 e.g. Art and Culture, 535, no. 416; 586–8; fig. 196, pl. 416.

42 Tsountas, C., ‘Κυκλαδικά ΙΙ’, Arch. Eph. 1899, 75, pl. 9. 11.Google Scholar

43 Ibid. pl. 8. 3; Emergence, 531, 533.

44 NM 4950, of the type Tsountas (n. 42), 99, fig. 26. See also Emergence, 531.

45 e.g. tombs 345, 355, 359, 408: see Tsountas (n. 42), 112–14. For tomb 355 see also Bossert, E.-M., ‘Ein Beitrag zu den frühkykladischen Fundgruppen’, Anadolu arastirmalari (1965), ii, pt. 1–2. 93, 95, 96, Abb. 3.Google Scholar

46 Caskey, J. L., ‘Ἀνασκαφαὶ ἐν Κέα̨,, 1969–70’, Ἐπετηρὶς τῆς Ἑταιρείας Κυκλαδικῶν Μελετῶν, 8 (1969–1970), 617, 618Google Scholar; Keos ii. 372 fig. 7. c 27, pl. 80. c 27; Wilson, and Eliot, , PC 78, 81, 83, fig. 2 d Google Scholar; Wilson, D. E., ‘Kea and East Attike in Early Bronze II: beyond pottery typology’, in Fossey, J. M. (ed.), McGill University Monographs in Classical Archaeology and History (Συνεισφορά McGill), 1 (1989), 42.Google Scholar

47 Phylakopi, 86, pl. 10. 6; Emergence, 529–31; Renfrew (n. 18), 23 n. 15.

48 Phylakopi 244, 248; Barber, R. L. N., ‘Phylakopi 1911 and the history of the Later Cycladic Bronze Age’, BSA 69 (1974), 4 Google Scholar; id., PC 89.

50 Emergence, 172, 529–31, 533; Art and Culture, 114.

51 Rutter, , Change, 6, 20 n. 5, 21 n. 11Google Scholar; ‘EC Period’, 151, ill. 3. 20; Barber, Cyclades, 94, fig. 59. 20.

52 Tsountas (n. 42), 85, pl. 9. 12. According to the NM catalogues grave 372 at Chalandriani contained the following offerings: (a) the above-mentioned clay bowl (NM 5143), (b) the silver pin NM 5144 (ibid. 101, pl. 10. 11), (c) the bronze pin NM 5145 (ibid. 101, pl. 10. 21, and not pl. 10. 19 as written here), (d) the spouted pyxis NM 5146 ( Åberg, N., Bronzezeitliche und früheisenzeitliche Chronologie, iv: Griechenland (Stockholm, 1933), 87, Abb. 167)Google Scholar and (e) the one-handled tankard NM 5306 (ibid. 89, Abb. 172).

53 NM 5187. Information taken from the NM catalogues.

54 Krassades, T 118: Tsountas, C., ‘Κυκλαδικά Ι’, Arch. Eph. 1898, 162, pl. 9. 40. Pelos Google Scholar: Edgar, C. C., ‘Pre-historic tombs at Pelos’, BSA 3 (1896–1897), 48, fig. 17.Google Scholar Christiana: Doumas, , Christiana, 5, pl. 3 δ, left.Google Scholar

55 Papathanasopoulos, G. A., ‘Κυκλαδικά Νάξου’, A. Delt. 17. 1 (1961–1962), Mel. 127–8, pl. 58 γ.Google Scholar

56 Ibid. pl. 58 α–β.

57 Ibid. 126, pl. 56 β: of the wide-necked variety. Compare with the similar jugs from Askitario ( Theocharis, D. R., Ἀσκηταριό· πρωτοελλαδική ἀκρόπολις παρὰ τήν ‘Ραφήναν᾿, Arch. Eph. 1953–1954, III 70. fig. 17)Google Scholar and Skyros ( Parlama, L., Η Σκύρος στην εποχή του χαλκού (Athens, 1984), 98. nos. 1–2; 99Google Scholar; fig. 17; pls 42–3).

58 For EC II vases bearing painted decoration of crosshatched triangles see: Zervos, C., L'Art des Cyclades du début à la fin de l'âge du bronze: 2500–1100 avant notre ère (Paris, 1957), fig. 233Google Scholar; Papathanasopoulos (n. 55), 116–18, pl. 49 β–δ, inserted plates Β–Γ; id.,Νεολιθικά–Κυκλαδικά· Εθνικό Αρχαιολογικό Μουσείο(Athens, 1981), pls. 80, 82–3; Zapheiropoulou, Ph., ‘Ὄστρακα ἐκ Κέρου’, AAA 8 (1975). 80, 82, figs. 3 α, γ, ε, ηGoogle Scholar; 5 α. See also a jug from Askitario: Theocharis (n. 57), 67, fig. 6. For other EC II vases with painted decoration of cross-hatching see: Zervos (see above), figs. 117, 122, 152, 154, 238; Papathanasopoulos (n. 55), 116, 139, pl. 49 α, 72 β, supplementary plate A; id.,Νεολιθικά –Κυκλαδικά (see above), pl. 81; Zapheiropoulou, AAA 8 (see above), figs. 3 β, 5 β; Art and Culture, 114, 528, pl. 385; ‘EC Period’, 149, ill. 3. 11; Marangou, L., ‘Evidence for the Early Cycladic Period on Amorgos’, in Fitton, J. L. (ed.), Cycladica: Studies in Memory of N. P. Goulandris (London, 1984), 101, no. 7, fig. 18.Google Scholar

59 Papathanasopoulos (n. 55), 126, pl. 56 α compare with Doumas, Burial Habits, 20, fig. 9 d (Syros group).

60 See also Rutter, Change, 15; Barber, , Cyclades, 28, 138, 249 n. 12Google Scholar; id., BSA 69 (n. 48), 48, for the possibility of a partial contemporaneity of the ‘Lefkandi I’ phase with Phylakopi I-i ( = EC II).

61 Popham and Sackett (n. 7), 8; Rutter, , Change, 6, 15, 22 n. 14, table 3Google Scholar; id., AJA 87 (n. 26), 69–70 n. 7, 72 n. 20; Sampson (n. 7), 149–51; Mellink (n. 7), 146, 149, 150, pl. 16 at p. 144; Doumas, Problems, 26–7. Disputing Rutter's view that the ‘Kastri group’ should be placed to the late part of the duration of EC II/EH II ( Rutter, , AJA 87 (n. 26), 71, 74Google Scholar; id., PC 95), Barber and MacGillivray maintained at first that ‘EC III A’ is contemporary with EH III ( Barber, , AJA 87 (n. 22), 81 Google Scholar; MacGillivray, , AJA 87 (n. 28), 81–3).CrossRefGoogle Scholar Later, however, they accepted its contemporaneity with late EH II and EH III on the Greek mainland (MacGillivray, PC 73; Barber, Cyclades, 29).

62 Wilson (n. 46), 35–49.

63 Ayia Irini III: Barber (n. 12), 368; id., Cyclades, 28, figs. 22–3; MacGillivray, Kynthos, 25; ‘EC Period’, 150; PC, chronological chart at p. 301; Caskey, , Hesp. 50 (n. 7), 321–2Google Scholar; Mellink (n. 7), 149, pl. 16 at p. 144. Kastri (Syros): MacGillivray, Kynthos, 7; ‘EC Period’, 150, 155, table 2; PC, chronological chart at p. 301; Mellink (n. 7), 149, pl. 16 at p. 144; Barber, , Cyclades, 28, 54, 70, 138, fig. 22Google Scholar; Doumas, , Problems, 23–4, 25.Google Scholar Panormos (Naxos): MacGillivray, Kynthos, 7; ‘EC Period’, 150, 155; Doumas, , Problems, 23–4, 25.Google Scholar Kynthos (Delos): ibid.

64 Emergence, 178; MacGillivray, , Kynthos, 8, 45 Google Scholar; ‘EC Period’, 149 n. 48, 150, 155, table 2; Barber, , Cyclades, 28, 56, 70, 138.Google Scholar

65 Doumas, C., ‘Notes on Early Cycladic architecture’, AA 87 (1972), 156, fig. 8Google Scholar; ‘EC Period’, 145. Note the divergence of views with regard to the dating of the ‘Kampos group’. Some consider it as the final stage of EC I: Bossert (n. 7), 75 n. 67; Jacobsen, T. W., ‘A group of Early Cycladic vases in the Benaki Museum in Athens’, AA 84 (1969), 236 n. 9Google Scholar; Emergence, 528; Coleman, J. E., ‘The chronology and interconnections of the Cycladic islands in the Neolithic period and the Early Bronze Age’, AJA 78 (1974), 341, 342CrossRefGoogle Scholar; Art and Culture, 64, 110; ‘EC Period’, 144, 145, ill. 2. 5; Papathanasopoulos,Νεολιθικά–Κυκλαδικά (n. 58), 145; others as a transitional stage between EC I and EC II: Doumas, Burial Habits, 24–5, fig. 7 a; id., Cycladic Art (n. 3), 12, 39, table 1; Renfrew, PC 51; Art and Culture, 22, 135, chronological table at p. 593; Coleman, J. E., ‘Chronological and cultural divisions of the Early Cycladic period: a critical approach’, in Davis, J. L. and Cherry, J. F. (eds), Papers in Cycladic Prehistory (University of California, Los Angeles, 1979), 50 Google Scholar; ‘EC Period’, 144, 148, ill. 2. 5; PC 296–7; Warren, ibid. 60; Zapheiropoulou, ibid. 38, 40; Barber, , Cyclades, 27, 89, fig. 22Google Scholar; and others as the earliest phase of EC II: Doumas, C., ‘Προϊστορικοὶ Κυκλαδιτ̃ες στὴν Κρήτη’, AAA 9 (1976), 70, 75Google Scholar; id. Art and Culture, 31; id., Cycladic Art (n. 3), 29; id., Problems, 22; Zaphiropoulou, Ph., ‘Un cimetière du Cycladique Ancien à Epano Kouphonissi’, in Rougemont, G. (ed.), Les Cyclades: matériaux pour une étude de géographie historique (table ronde réunie à l'Université de Dijon les 11, 12 et 13 mars 1982) (CNRS, Paris, 1983), 83 Google Scholar; Coleman, J. E., ‘“Frying pans” of the early bronze age Aegean’, AJA 89 (1985), 197, 201CrossRefGoogle Scholar; Sakellarakis, E., ‘New evidence from the early bronze age cemetery at Manika, Chalkis’, BSA 82 (1987), 253, 255.Google Scholar

66 ‘EC Period’, 147, table 2; Barber, , Cyclades, 56, 138.Google Scholar

67 Keos ii. 370; Caskey, , Hesp. 50 (n. 7), 322 Google Scholar; Rutter, Change, 4; ‘EC Period’, 150, 151; MacGillivray, PC 70; Wilson and Eliot, ibid. 81–3.

68 Wilson and Eliot, PC 83; Wilson (n. 46), 36.

70 Ibid. 69, 72, Abb. 3. 1.

71 Tsountas (n. 42), 122.

72 Ibid.

73 Ibid.; Bossert (n. 7), 70, 73, Abb. 5. 3–4; Emergence, 533.

74 e.g. Tsountas (n. 54), 154, pl. 9. 26; id. (n. 42), 98, 114, pl. 8. 10; Åberg (n. 52), 85, Abb. 160; Theocharis (n. 57), 67–8, fig. 6; Zervos (n. 58), figs. 231–2; Papathanasopoulos (n. 55), 126, pl. 56 α; Emergence, pl. 7. 3; Doumas, Burial Habits, 20–1, fig. 9 d; id., Cycladic Art (n. 3), 148, no. 181; Art and Culture, 112–13, 535, 586–8, pl. 416; ‘EC Period’, 149–50, ill. 2. 14; Marangou (n. 58), 101, inv. no. 47, fig. 13; Barber, Cyclades, 92, fig. 58. 14.

75 Tsountas (n. 42), 85, pl. 9. 17.

76 Zervos (n. 58), figs. 89–91.

77 Tsountas (n. 54), 174, 182, like pl. 9. 39.

78 Ibid. 154.

79 Ibid. 167, 182–3.

80 Personal communication with Dr D. Wilson.

81 Doumas, Christiana, 7; id., ‘The Minoan thalassocracy and the Cyclades’, AA 97 (1982), 8; id., Thera: Pompeii of the Ancient Aegean(London, 1983), 27; Wilson, D. E., ‘Pottery and architecture of the EM II A West Court House’, BSA 80 (1985), 358, 359.Google Scholar

82 Keos ii. 358, P 17; pl. 76, P 17.

83 Ibid. 366, B 44; pl. 79, B 44; Wilson and Eliot, PC 83; Wilson (n. 46), 40, no. 1.

84 Plassart, A., Les Sanctuaires et les cultes du Mont Cynthe (Exploration archéologique de Délos, xi; 1928), 35, 40, figs. 34, 38Google Scholar; MacGillivray, Kynthos, 41, nos. 392, 408–10; figs. 15. 392; 20. 408–10.

85 Tsountas (n. 54), 174, pl. 9. 37.

86 Doumas, , Burial Habits, 102, ii–c; 118, no. 35, pl. 44 e.Google Scholar

87 Id.,‘Κορφὴ τ’ Ἀρωνιοῦ · μικρὰ ἀνασκαφικὴ ἔρευνα ἐν Νάξω̨’,A. Delt. 20. 1 (1965). Mel. 46, pl. 33 β.

88 MacGillivray, Kynthos, 44, n. 133; Doumas, AA 97 (n. 81), 8.

89 Phylakopi, 86; Doumas, , AA 97 (n. 81), 8.Google Scholar

90 Tsountas (n. 54), 153.

91 Marangou (n. 58), 100, figs. 2–4, 7–9.

92 Doumas, , AA 97 (n. 81), 8 Google Scholar; id., Thera (n. 81), 27.

93 Id., Christiana, 7.

94 MacGillivray, PC 75.

93 Ibid.

96 See n. 69.

97 See n. 94.

98 See n. 35.

99 Mellink (n. 7), 148–9.

100 See n. 34.

101 Keos ii. 373–5, fig. 7, pl. 80.

102 See n. 37.

103 Doumas, C., ‘Κυκλάδες· κέρος, Νάξος’, A. Delt. 19 (1964), Chr. B3, 411–12Google Scholar; id., AA 87 (n. 65), 156, 165–6; Emergence, 177–8.

104 Doumas, , AA 87 (n. 65), 165.Google Scholar

105 Id., Christiana, 8 n. 2; Rutter, Change, 21 n. 13, table 1; ‘EC Period’, 150.

106 MacGillivray, Kynthos, 44 n. 133; Doumas, , AA 97 (n. 81), 8.Google Scholar

107 Emergence, 178.

108 Doumas (n. 103), 412; Emergence, 178.

109 Doumas (n. 103), 412.

110 See discussion of the EC II features from the Kastri fort, and nn. 73, 81 above.

111 MacGillivray, J. A., Early Cycladic Pottery from Mt. Kynthos in Delos (1979)Google Scholar; id., Kynthos, 8–45.

112 Doumas, Burial Habits, 25, 26; id., Problems, 26; ‘EC Period’, 150, 155, table 2; PC, chronological chart at p. 301; Barber, Cyclades, 21, fig. 22.

113 Doumas, Christiana, 8.

114 Tsakos, K., ‘Ἀρχαιότητης καὶ μνημεῖα Σάμου καὶ Κυκλάδων’, A. Delt. 22 (1967), Chr. B2, 464. pl. 341 βGoogle Scholar; Doumas, Christiana, 5, fig. 6, pl. 3 γ.

115 Tsakos (n. 114), pl. 341 α Doumas, , Christiana, 5, fig. 4, pl. 1 Google Scholar β, left.

116 Tsakos (n. 114), pl. 341 γ, Doumas, Christiana, 3–4, figs. 3, 5, 9; pls 2 α, 3 α–β, 5 ε.

117 Ibid. 3–4. figs. 1–2; pl. 1 α–β, right.

118 Ibid. 5, figs. 8, 10; pls. 2 β, 5 ζ.

119 Ibid. 5, pl. 3 δ, left.

120 Ibid. 7.

121 See also Rutter, Change, 20 n. 5: ‘This (Christiana) pottery lacks evidence for any of the type shapes of the “Kastri group”’.

122 Keos ii. 372, fig. 6. c 11, pl. 81, c 12.

123 MacGillivray (n. 111), 14, fig. 11. 91; id., Kynthos, 23, fig. 7. 91.

124 Bosanquet, R. C., ‘Notes from the Cyclades’, BSA 3 (1896–1897), 56–7, no. 4, fig. 4Google Scholar; Barber, , BSA 69 (n. 48), 42, fig. 9 (MM 337)Google Scholar; ‘EC Period’, 153, EC III B, ill. 2. 23.

125 Phylakopi, 143, pl. 33. 1–2; Rubensohn (n. 12), 23, Abb. 15; Forsdyke, E. J., Catalogue of the Greek and Etruscan Vases in the British Museum, i. 1 : Prehistoric Aegean Pottery (London, 1925), 64, A 346–7, pl. 4, A 346Google Scholar; Emergence, 187, fig. 12. 1. 1 (MM A 346); Barber, , BSA 69 (n. 48), 6 Google Scholar, no. 241, 9, nos. 144–6, 147 (MM 96), 42, no. 6 (MM 334), MM 57, MM 333, MM 429, fig. 9. 6 (MM 334), pl. 7 a; Doumas, Burial Habits, 24, fig. 13 g.

126 See discussion, above, of the dating of the forms considered characteristic of the ‘Kastri group’.

127 See discussion about the EC II features from the Kastri fort above.

128 Bossert (n. 7), 70, 73, Abb. 5. 5; Emergence, 173, fig. 11. 2. 2.

129 MacGillivray, Kynthos, 18, fig. 5. 104 (group B).

130 See discussion about the EC II features from the Kastri fort (above).

131 ‘EC Period’, 150.

132 Rutter, , AJA 87 (n. 26), 69 n. 6, 70 n. 10, 71 n. 17.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

133 Ibid. 71 n. 17.

134 For the possibility of an overlap in date between the ‘Kastri group’/EC III A and Phylakopi I–ii/early EC III B see: Emergence, 535; Barber, , BSA 69 (n. 48), 48, fig. 10Google Scholar; id. (n. 12), 368; id., ‘A tomb at Ayios Loukas, Syros: some thoughts on Early–Middle Cycladic chronology’, Journal of Mediterranean Anthropology and Archaeology, 1. 2 (1981), 177; Art and Culture, chronological table at p. 593; Doumas, Burial Habits, 26; id., Problems, 24, 25, 28; Rutter, Change, 22 n. 15; ‘EC Period’, 151 n. 86; MacGillivray, , PC 73, 75 Google Scholar; Sotirakopoulou, , BSA 81 (n. 24), 309.Google Scholar For the dating of Phylakopi I–ii to the early phase of EC III B see: Barber, , BSA 69 (n. 48), 4 Google Scholar; id., PC 89, 92; id., Cyclades, 29, fig. 22; ‘EC Period’, 151, table 1; PC, chronological chart at p. 301; Doumas, Problems, 28. For the attribution of the ‘Dark-faced pottery’ to Phylakopi I–ii see: Phylakopi, 87, 249; Barber, , BSA 69 (n. 48), 4 Google Scholar; id., ‘A tomb at Ayios Loukas’ (see above), 175; id., PC 89, 92; id., Cyclades, 29, 94–5; ‘EC Period’, 152.

135 Rutter, , Change, 20 n. 5.Google Scholar

136 Emergence, 192, 194; Doumas, , Burial Habits, 23 Google Scholar; Barber, , AJA 87 (n. 22), 80 Google Scholar; id., PC 90–1; id., Cyclades, 94–5; MacGillivray, , AJA 87 (n. 28), 83 Google Scholar; id., PC 75.

137 Barber, , PC 91.Google Scholar

138 Emergence, 194; Doumas, Burial Habits, 24; Barber, , AJA 87 (n. 22), 80 Google Scholar; id., PC 91.

139 See n. 117.

140 Phylakopi, 91, no. 5; Forsdyke (n. 125), 59–60, A 331, fig. 69; pl. 5, A 331; Zervos (n. 58), figs. 130, 132; Art and Culture, 114, 536, pl. 419.

141 For examples from Christiana, Ayia Irini III, and Kynthos group B see nn. 118, 122–3.

142 For examples of these types of bowls see nn. 124–5. For the derivation of the Phylakopi I/‘EC III B’ bowls from the ‘EC III A’ ones see also Barber, , AJA 87 (n. 22), 80.Google Scholar MacGillivray, ibid. (n. 28), 83.

143 Barber, PC 92.

144 Sampson (n. 7), 149, has also placed the ‘Kastri group’ between the EB 2 ‘Keros–Syros’ and the EB 3 ‘Phylakopi I culture’.

145 See n. 61.

146 Rutter, , Change, 17, 22 n. 14Google Scholar; id., AJA 87 (n. 26), 69–70.

147 Sampson (n. 7), 149.

148 One-handled tankards: Konsola, D., Προμυκηναϊκή Θήβα· χωροταξική και οικιστική διάρθρωση (Athens, 1981), 92, 122, fig. 3 δ.Google Scholar

150 Two-handled tankards: ibid. 92, 122, fig. 3 ε, στ.

151 Ibid. 92, 123, 145–6.

152 Ibid. 144. For the contextual associations of the ‘Lefkandi I’ pottery at Thebes and Orchomenos see also Sampson (n. 7), 151.

153 Konsola (n. 148), 146; Demakopoulou, K. and Konsola, D., ‘Λείψανα ΠΕ, ΜΕ καὶ YΕ οἰκισμοῦ στὴ θήβα’, A. Delt. 30. 1 (1975). Mel. 85–6.Google Scholar

154 Emergence, 103.

155 Ibid.

156 See n. 26.

157 Rutter, , AJA 87 (n. 26), 70.Google Scholar

158 MacGillivray, ibid. (n. 28), 81–3 (see also n. 61).

159 Ibid. 82, 83.

160 Sampson (n. 7), 149, 150, too, though placing the ‘Kastri’ phase in the late part of the duration of EC II/EH II, he accepts that it has some correspondence with Troy IV and Lerna IV, stating, however, that this does not mean that ‘Kastri’ belongs to EH III.

161 On the basis of the resemblances he observed between the type shapes of Lerna IV and those of Lefkandi I, Rutter proposed in 1979 the theory that ‘the EH III pottery of Lerna IV and Lefkandi II is the product of a mingling of an intrusive Western Anatolian tradition represented by the ‘Lefkandi l'assemblage and the native mainland Greek tradition of EH II’ (Rutter, Change, 10) and ‘the result of the “bridging” at both sites of the vast differences that existed between the pottery of Lefkandi I and Lerna III’ (ibid. 12).

162 Sampson (n. 7), 149.