Introduction

Landscapes are widely recognised as precious ecological, environmental and cultural assets, as well as key contributors to individual and social well-being (Council of Europe 2000). Their character is shaped by both natural processes and human activities over thousands of years as a result of the interplay between demographic, technological, socio-economic, cultural and environmental forces (Ellis et al. Reference Ellis, Kaplan, Fuller, Vavrus, Goldewijk and Verburg2013).

Terraces are characteristic elements of landscapes in many regions around the world. They provide versatile units for arable or polycropping (with fruit or olive trees, as well as cereals), and can also be grazed if uncultivated. Agricultural and environmental research has suggested the benefits of terracing for soil management and controlling moisture levels (Grove & Rackham Reference Grove and Rackham2001). Terraces are highly variable, their regional development reflecting a combination of natural factors (e.g. geologies, geomorphologies and hydrological conditions) and landscape histories (e.g. ownership patterns, manuring practices, field management and crop selection) (Varotto et al. Reference Varotto, Bonardi and Tarolli2019). Terraces are also connected to the heritage values of landscape, and their scenic qualities contribute strongly to regional landscape character (Pedroli et al. Reference Pedroli, Tagliasacchi, van der Sluis and Vos2013). Terraced landscapes are part of UNESCO World Heritage Sites in Africa, the Americas, Europe and Asia, and in November 2018, UNESCO added the dry-stone walling associated with terraces in Croatia, Spain and Greece to its list of Intangible Cultural Heritage.

Despite their agricultural, ecological and heritage values, the histories of terraced landscapes remain poorly understood (Bevan & Connolly Reference Bevan and Conolly2011; Nanavati et al. Reference Nanavati, French, Lane, Oros and Beresford-Jones2016) and better knowledge of historic practices is required to underpin future policies for sustainable land-use (Denevan Reference Denevan1995; Krahtopoulou & Frederick Reference Krahtopoulou and Frederick2008). This lack of understanding has hampered broader research on the histories of landscapes, limiting knowledge of how settlements operated within their wider landscapes, and of how terraces reflect the long-term investment choices made by rural communities (Ferro-Vázquez et al. Reference Ferro-Vázquez, Lang, Kaal and Stump2017; and as illustrated by the number of terrace studies in the Mediterranean; Figure 1).

Figure 1. Map of the Mediterranean, with the location of study areas presented in this article: A) Boğsak, Turkey; B) Urla, Turkey; C) Naxos, Greece; D) Catalonia, Spain; E) Galicia, Spain. Previous studies include: 1) southern Greece (Foxhall et al. Reference Foxhall, Jones, Forbes, Alcock and Osborne2007); 2) Kea (Whitelaw Reference Whitelaw, Cherry, Davis and Mantzourani1991); 3) Lesvos (Schaus & Spencer Reference Schaus and Spencer1994; Kizos & Koulouri Reference Kizos and Koulouri2006); 4) Kythera and Antikythera (Krahtopoulou & Frederick Reference Krahtopoulou and Frederick2008; Bevan et al. Reference Bevan, Conolly, Colledge and Stellatou2013); 5) southern France (Harfouche Reference Harfouche2007); 6) Cyprus (Wagstaff Reference Wagstaff, Bell and Boardman1992); 7) Galicia, north-west Spain (Ballesteros-Arias et al. Reference Ballesteros-Arias, Criado-Boado, Bolós and Vicedo2009; Ferro-Vasquez et al. Reference Ferro-Vasquez, Kaal, Arévalo and Boado2019); 8) Israel (Davidovich et al. Reference Davidovich, Porat, Gadot, Avni and Lipschits2012; Porat et al. Reference Porat, Davidovich, Avni, Avni and Gadot2018, Reference Porat, López, Lensky, Elinson, Avni, Elgart-Sharon, Faershtein and Gadot2019); 9) Jordan (Kuijt et al. Reference Kuijt, Finlayson and Mackay2007; Beckers et al. Reference Beckers, Schütt, Tsukamoto and Frechen2013); 10) Crete (Betancourt & Hope Simpson Reference Betancourt and Simpson1992); 11) Murcia, south-east Spain (Puy & Balbo Reference Puy and Balbo2013); 12) Catalonia, north-east Spain (Boixadera et al. Reference Boixadera, Riera, Vila, Esteban, Albert, Llop and Poch2016); 13) Pyrenees, France (Rendu et al. Reference Rendu2015); 14) Ebro Valley, Spain (Quirós-Castillo & Nicosia Reference Quirós-Castillo and Nicosia2019) (figure by T. Kinnaird).

The main reason for this lack of knowledge is that terraces have proven exceptionally difficult to date using archaeological and scientific methods (Acabado Reference Acabado2009). Although datable artefacts are sometimes recovered during excavation (Koborov & Borisov Reference Koborov and Borisov2013), disturbance and bioturbation frequently complicate their interpretation; more often, such artefacts are altogether absent. Retrogressive analysis as part of GIS-based landscape studies can reveal the sequential relationships between landscape features, suggesting the order in which earthworks developed. Such methods, however, only allow construction of relative chronologies, as opposed to providing absolute dates (Crow et al. Reference Crow, Turner and Vionis2011). Radiocarbon methods can be applied to buried soils, and Bayesian modelling has been used to refine the interpretation of radiocarbon results for terraces (Acabado Reference Acabado2009). But buried soil horizons are often missing, bulk samples tend to yield overestimates of ages due to the presence of older carbon fractions in the environment, and interpretation can also be complicated by problems of ‘old wood’ (Puy et al. Reference Puy, Balbo and Bebenzer2016; Ferro-Vasquez et al. Reference Ferro-Vasquez, Kaal, Arévalo and Boado2019). Luminescence dating, which can be used to determine when certain minerals were last exposed to light or were heated, has also been used to date terrace soils and constructional fills (Davidovich et al. Reference Davidovich, Porat, Gadot, Avni and Lipschits2012; Porat et al. Reference Porat, Davidovich, Avni, Avni and Gadot2018). Nevertheless, luminescence and radiocarbon dating both have an inherent limitation: the dates relate only to the specific position sampled in the soil profile. A recently developed, innovative approach for dating earthwork features and agricultural terraces represents a major advance in dealing with this problem (see Kinnaird et al. Reference Kinnaird, Bolòs, Turner and Turner2017a; Turner et al. Reference Turner, Bolòs and Kinnaird2018).

Five study areas in three countries (Spain, Greece and Turkey) (Figure 1A–E) were selected in order to test the applicability of the new methods to different climatic, topographical and geological zones. This geographical distribution represents a range of soils and sediments, from dystric cambisols in Naxos, calcaric cambisols and leptosols in Catalonia, to mollic cambisols in Galicia (Panagos et al. Reference Panagos, van Liedekerke, Jones and Montanarella2012; European Soil Data Centre 2020). This geographic distribution also affords the possibility of identifying regional chronologies or variations in terrace construction and use. Terraces in all five study areas were sampled as part of collaborative, international fieldwork projects focused on understanding long-term landscape history.

Methodology

Within each region, the team identified terrace systems with a range of different morphological characteristics, using GIS-based historic landscape characterisations (HLCs; Turner Reference Turner, Fairclough, Sarlov-Herlin and Swanwick2018; stage one in Figure 2). Six basic types of Mediterranean terraces—braided, step and pocket terraces, check-dams, terraced fields and false (bulldozed) terraces—have previously been identified by historical ecologists (Grove & Rackham Reference Grove and Rackham2001), although their form varies between and within regions. In Catalonia, for example, historic terraces in some areas lack walls entirely, whereas rubble or rough ashlar walls are normal in other places. In the Aegean, zig-zag braided terraces are most common, but terraced fields and step terraces (either straight or curving round the hillside) are also common. The terrace character types used for our HLC analyses were based on these six basic types. In each region, our work focused on the most characteristic type(s) of terrace in that area.

Figure 2. Stages one to five of the methodology: stage one) initial HLC and site selection; stage two) OSL field profiles used to create hypotheses about earthwork development and target soil/sediment samples for subsequent laboratory analysis; stage three) OSL laboratory screening and sample selection for dating (for details, see Figure 3); stage four) quartz SAR-OSL dating of selected samples (for details, see Figure 4); stage five) interpretation and use of results to refine HLC and landscape modelling (figure by T. Kinnaird).

In this research, portable optically stimulated luminescence (OSL) equipment (Sanderson & Murphy Reference Sanderson and Murphy2010), coupled with in situ gamma spectrometry, was used to contextualise soil-sediment ‘luminescence stratigraphies’ on-site and in real-time, directly relating the sediment sequences with the archaeological contexts (Kinnaird et al. Reference Kinnaird, Bolòs, Turner and Turner2017a & Reference Kinnaird, Dawson, Sanderson, Hamilton, Cresswell and Rennellb; Porat et al. Reference Porat, López, Lensky, Elinson, Avni, Elgart-Sharon, Faershtein and Gadot2019). This approach has two key advantages. First, constraining and characterising the chronological sequences of the soil profiles enables better informed and more effective sampling strategies. OSL profiling generates relative sediment ‘chronologies’, which allows for direct correlations between sediment units, and the means to relate discrete features across the sites. These proxy luminescence data form the basis for generating hypotheses concerning the construction and later modification of the earthworks and terraces. The luminescence profiles are used in the field to identify specific sedimentary horizons with probable archaeological significance (in particular, construction events, evidence of repair or modification), which can then be targeted for OSL dating or other geoarchaeological analyses.

Second, by combining this approach with subsequent laboratory analysis, it is possible to assess the ‘chronology’ of the whole sediment profile in a terrace, rather than having to rely on a small number of quantitative dates from arbitrarily selected points in the profile. This means that discrete soil/sediment units can sometimes be identified and related to the construction or modification of the earthwork or terrace. Our methodology for dating the construction sequences of agricultural features is summarised in Figure 2, and is described in further detail in the online supplementary material (OSM).

Figures 3–4 illustrate the progression from field profiling and hypothesis development (stage two in Figure 2) to OSL characterisation and screening in the laboratory (stage three), then quartz single-aliquot regenerative (SAR) OSL dating (stage four). Figure 3 illustrates examples of the hypotheses raised during fieldwork, based on observations of the sedimentology, archaeology and trends in proxy luminescence data. A gradual increase in OSL and infrared stimulated luminescence (IRSL) signal intensity with depth might suggest that the sediments in the profile built up steadily over time, whereas an ‘inverted’ progression—where sediment with higher intensities overlies sediment with lower intensities—might indicate material that had previously been buried elsewhere, then subsequently re-deposited by natural or human processes. The range of intensities across these progressions may indicate the relative rates of sedimentation; sudden breaks in signal intensity may correspond to discontinuities or hiatuses in deposition. Trends in IRSL and OSL depletion indices down the profile may indicate the extent to which the luminescence signal mixes an ‘inherited’ dose built up in a previous location, while the IRSL:OSL ratios may reflect changes in mineralogy.

Figure 3. Hypothesis testing: progression from preliminary OSL screening in the field (stage two) to calibrated OSL characterisation in the laboratory (stage three).

Figure 4. Progression from laboratory OSL screening and characterisation (stage three) to quantitative quartz SAR OSL dating (stage four) (figure by T. Kinnaird).

In the first scenario shown in Figure 3 (left), the terrace has been constructed by cutting directly into the bedrock slope, with a stone wall built to retain the upper slope. Potential targets for dating may include any materials exposed to light (and therefore ‘bleached’ and ‘reset’) at the time of construction that are now beneath the wall, or any materials that subsequently filtered down the void between the wall and the bedrock cut slope. Such materials may correspond to minima in signal intensities at depth. This hypothesis is tested in stage three: if the basal sediments are marked by minima in apparent dose values, samples should be progressed to dating at stage four (Figure 3: example one). If not, then the sediment was probably not sufficiently disturbed at the time of construction to reset the luminescence dating signals, and the dating samples should be retained (Figure 3: example two).

Alternatively, a terrace may be constructed by cutting into the bedrock slope, raising a stone or earth retainer, and then filling the void behind the retainer with sediment. This space might be infilled at construction (scenario two; Figure 3: middle), or by gradual accumulation (scenario three). Additional dating priorities would be located at the base of the anthropogenic fill (scenario two), or throughout the sediment accumulation (scenario three; Figure 3: right). The field profiles are likely to provide some insights into the construction sequence. If the sediment beneath the retainer is marked by minima in signal intensities, this sediment may have been disturbed at construction. If signal intensities are inverted, or if there is no signal-depth progression, then the fill may have been deposited rapidly. If there is a signal-depth progression, then this can elucidate whether sedimentation was uniform or episodic, gradual or rapid. These hypotheses can be tested and refined in stage three. Inverted or similar apparent doses with depth through the fill might imply that the sediment was deliberately re-deposited or packed (Figure 3: example three). The magnitude and range in apparent doses through the fill(s) provide a first approximation for depositional age(s): if dose rates were uniform, and sedimentological and mineralogical characteristics are relatively homogeneous, then the ratio between top and bottom provides some indication of chronology. Steps or substantial shifts in apparent doses with depth probably indicate where there have been hiatuses in deposition, or where erosion has occurred. The reproducibility between aliquots can provide an indication of how well bleached the sediment was at deposition: good reproducibility suggests it was well bleached, poor reproducibility that it was poorly bleached (Figure 3: example five). Heterogeneous distributions of sensitivity and apparent dose through the sediment stratigraphies imply complex depositional histories, and samples should be progressed to dating with caution (Figure 3: examples four & six). An applied example of this methodology is illustrated below.

Case study: Geçirim-Kuzkuyusu, Mersin, Turkey

To illustrate the field and laboratory methods that have been applied in all five study areas, we present a case study based on one example of a terrace system in southern Turkey (Figure 1A). The fieldwork was undertaken within the framework of the Boğsak Archaeological Survey project, a multi-disciplinary and diachronic archaeological research programme that includes the documentation, study and analysis of terrestrial and submerged material remains, as well as aspects of intangible heritage (Varinlioğlu Reference Varinlioğlu and Rizos2017). The project comprises several sub-fields, including landscape, maritime, and architectural survey, archaeometric and geoarchaeological analysis, and ethnographic and anthropological research. To date, detailed survey and recording has focused on Roman and late antique remains on the islands of Boğsak (ancient Asteria) and Dana (and the adjacent shores), which lie in the Taşucu Gulf to the west of Silifke, on Turkey's southern Mediterranean coast (Varinlioğlu Reference Varinlioğlu and Rizos2017; Varinlioğlu et al. Reference Varinlioğlu, Kaye, Jones, Ingram and Rauh2017). While the coastal area has seen increasing industrialisation and urbanisation in recent decades, the mountainous hinterland of Boğsak has witnessed a growing level of abandonment, as farmers and transhumant pastoralists have increasingly moved to towns and cities. Extensive field survey in this area has identified the remains of settlements, as well as agricultural and industrial facilities, dating from the Chalcolithic onwards (Mac Sweeney & Şerifoğlu Reference Mac Sweeney, Şerifoğlu, Heffron, Stone and Worthington2017).

HLC analysis of Boğsak's hinterland, carried out between 2015 and 2018, has highlighted the range of landscape character types found in the region. As none of the agricultural terraces in the area had been dated archaeologically, fieldwork was undertaken at five sites to ground-truth the HLC analysis, and to date the creation and development of key terrace examples using OSL profiling and dating (OSL-PD). Fieldwork at one of these sites, located between Geçirim and Kuzkuyusu near the centre of the Boğsak study area, is presented here.

HLC analysis of the landscape surrounding a deserted settlement of unknown date identified five different types of field systems: strip fields, rectilinear fields, maquis fields, braided terraces and check dams (Figure 5). This classification was checked and verified during fieldwork in November 2016. The deserted settlement has a commanding view of the surrounding agricultural lands. To the east lie several valleys running down from a north–south ridge to the more open arable land below. The enclosed slopes are concave—steeper towards the ridge and gentler towards the valley bottom. These enclosed areas are extensively terraced, with individual ‘fields’ separated by stone walls every 10–20m downslope. The walls, whose age was unknown, stand 0.50–0.80m tall. The sediment sequences associated with three check dams in two adjacent valleys were examined, and samples collected for OSL-PD, each with the aim of defining sediment chronologies and modelling the construction sequences. Figure 5 shows the distribution of the terrace walls investigated, together with the luminescence stratigraphies generated for the associated sedimentary sequences.

Figure 5. Case study: ancient site between Geçirim and Kuzkuyusu, with fields, check dams and terraces on slopes: a) historic landscape characterisation (HLC); b) luminescence stratigraphies (figure by T. Kinnaird).

Terraces one and two were located in the southerly valley (Figure 5). Terrace one was located low down in the valley, close to the topographic break between the steep slope and flat low-lying land. This was a check-dam, faced with a drystone wall standing 0.50m tall. The sediment profile (P10) comprised approximately 0.35m of brown agricultural soil, then a 50mm-thick C horizon, before bedrock was encountered at a depth of 0.40m. Five bulk sediment samples were taken at approximately 50mm intervals down profile for OSL profiling. This series shows that the luminescence-depth profile is inverted from the surface to approximately 0.35m deep, with maximum intensities at 0.18m; the lowest sample is characterised by low signal intensities. This was interpreted in the field as reflecting deposition from hillwash/downslope movement of soils, with the spike in intensities at 0.18m potentially reflecting a failure of soil management upslope.

Check dam two was located high in the same valley, close to the ridge above. The facing wall (0.80m tall) protected a sediment profile (P11), which comprised alternating horizons of brown silt loam and more calcitic silt loams, with the latter more rubbly in nature. These rubbly horizons were attributed in the field to the construction of the terrace. Eight bulk sediment samples were collected through this profile. Signal intensities are inverted from the surface to approximately 0.41m deep, then increase with depth through the interval 0.41–0.58m, before dropping off from 0.58m. This was interpreted in the field as reflecting deposition from hillwash, ‘packing’ during construction with mixed age materials, and disturbance or bleaching of the substrate at deposition.

The final check dam sampled, terrace three, was located towards the top of the slope, in the adjacent coombe to the north (Figure 5). Its facing wall stood 0.80m tall, and was found to be the best constructed of the three structures investigated. The sediment profile (P12) consists of approximately 0.35m of brown, agricultural soils, overlying a 0.20m cobble horizon, which, in turn, overlay a buried, brown, compact soil. Eight bulk sediment samples were collected through this profile, which extended to bedrock at a depth of 0.87m. Initial impressions were that the agricultural soil had accumulated slowly over time, that there was a short chronology to the cobble horizon and that the buried soil represented a longer and more stable accumulation.

In summary, all the profiles exhibited aggradation over time, with stratigraphic breaks indicative of changes in erosional and depositional processes. In the case of those profiles containing a buried soil, the signal intensities at the base of the sediment stratigraphies were consistent with these units having been bleached at deposition. This probably resulted from disturbance of the buried soil during construction of the terrace wall. Accordingly, samples for OSL dating were positioned at the base of the sediment stratigraphies, above the R horizon (or bedrock). It was noted during fieldwork that the magnitude and range in signal intensities recorded in these sediments implied that there was some chronology to the sequence of construction: terrace three in the northerly valley was considered likely to be the oldest and terrace one the youngest; terrace two may have been constructed sometime between the other two.

These assumptions were tested in the subsequent programme of analytical work. The magnitude and range in apparent dose estimates across the investigated sediment stratigraphies supported the chronological framework suggested above for construction (Figure 5). The trends and maxima in apparent dose estimates supported the suggestion that the lower units in each of the sediment stratigraphies were disturbed and bleached during construction. In situ gamma dose-rate measurements implied no dosimetric gradients or discontinuities. This justified the positioning of the dating samples at the base of the sediment stratigraphies.

The construction of the terraces in the southern valley is dated to AD 1340±50 (terrace two) and AD 1850±20 (terrace one), upslope and downslope, respectively (see the OSM). The terrace wall in the northern valley was constructed sometime after AD 430±100. Apparent ages were retrospectively determined for each profiling sample (see the OSM). Our sediment chronologies imply that deposition of the agricultural soils from 0m to a depth of approximately 0.35m (0.38m in P10, 0.32m in P11, 0.36m in P12) was synchronous across the study region (after the early nineteenth century AD), and further corroborate the construction sequence for walls one to three. The evidence for this is:

1) The agricultural soils in P10, P11 and P12 have similar compositions.

2) Sub-samples at a depth of approximately 0.35m in each profile return apparent dose estimates in the range of around 0.4–0.5 Gy.

3) In situ gamma spectrometry implies no local variations in environmental dose rate. The sediment chronologies indicate that the greatest time-depth in P11 and P12 was from 0.40m to bedrock, potentially spanning 400 and 800 years, respectively.

This case study illustrates the methods used in each of the five study regions to identify suitable sites for sampling, and subsequently to profile and analyse them in the field and the laboratory. It demonstrates that OSL profiling at the time of archaeological survey is an extremely powerful tool for the interpretation of the sedimentary stratigraphies associated with terraces and other earthwork boundaries.

Results and discussion

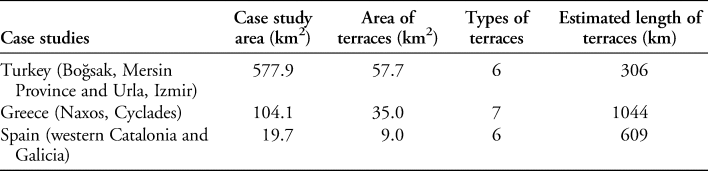

Table 1 summarises the spatial coverage of each of the HLCs (between approximately 20 and 600km2), the estimated total length of the terraces in each of the five study areas (>300km), and the number of terrace types identified in each area based on their morphologies.

Table 1. Historic landscape character types with agricultural terraces in three Mediterranean countries

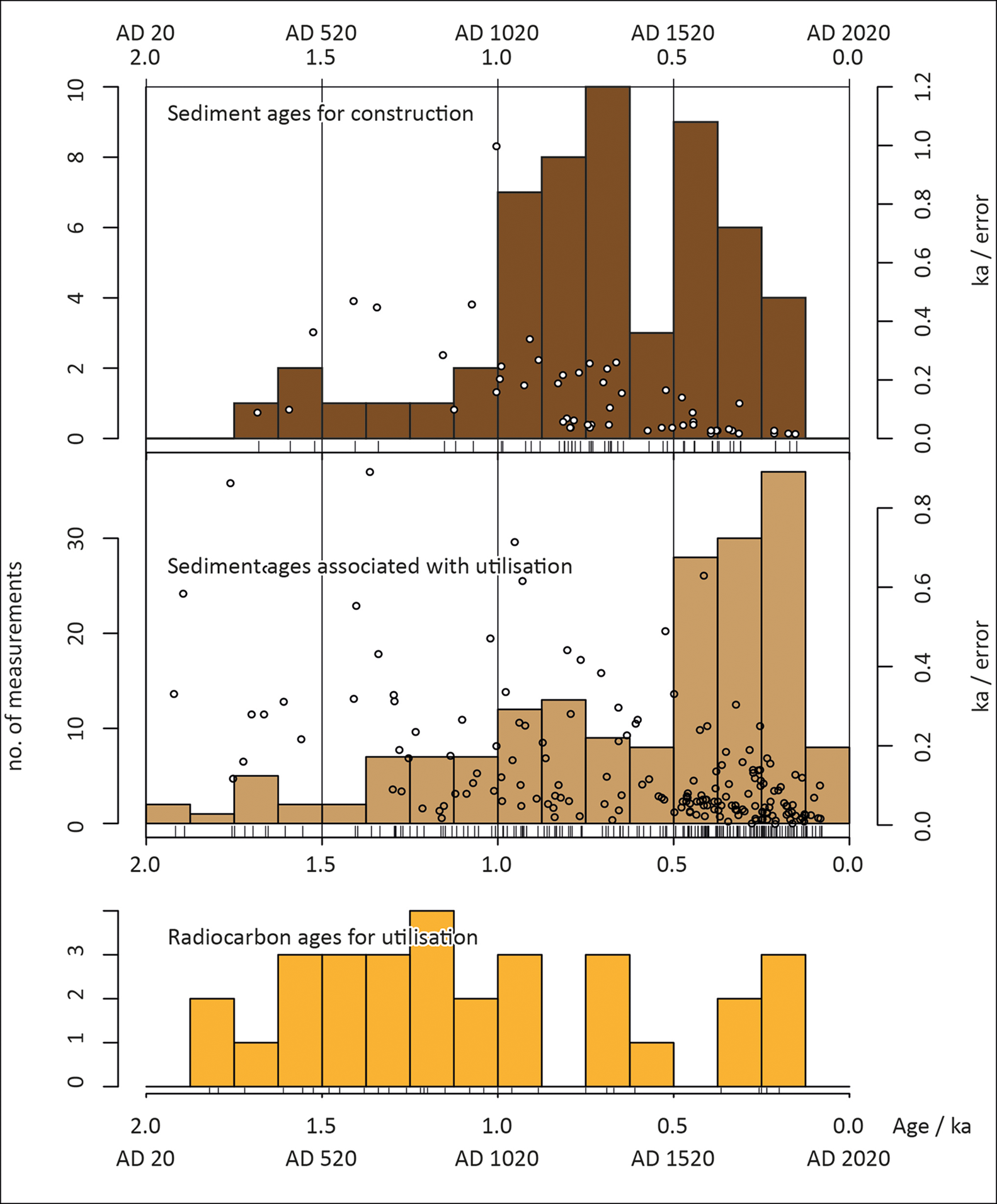

Figures 6–7 summarise our age constraints for terrace construction and utilisation across the Mediterranean region (also tabulated in the OSM). The data are drawn from the agricultural terraces and earthworks surveyed in the five case studies, sub-divided into 16 sub-regions, examined through 52 profiles comprising approximately 528 field and 357 laboratory samples and 65 dating samples (see Table S1 in the OSM). The total dataset comprises 283 temporal constraints in the 0–2 ka range on terrace construction and utilisation: 55 sediment ages relating to terrace construction or substantial modification and 228 apparent ages calculated from the calibrated dataset (for terrace utilisation). In addition, we compiled 42 previously published radiocarbon ages. The results are presented as follows: first, sediment ages linked to terrace construction; second, sediment ages linked to utilisation and modification of terraces; and third, radiocarbon ages interpreted here as also representing utilisation. OSL and radiocarbon dates are binned in 125 year intervals. The horizontal axis is limited to the last 2000 years, as the majority of the OSL and radiocarbon data date construction and utilisation to this period.

Figure 6. Individual quartz SAR-OSL depositional ages obtained for sediments associated with terrace construction in each case study (figure by T. Kinnaird).

Figure 7. Quartz OSL constraints for a) construction (brown) and b) utilisation (tan) (figure by T. Kinnaird).

Our dataset implies that terrace modification and utilisation was continuous throughout the last 2000 years, although patterns of terrace development varied. In some cases, existing systems were gradually subdivided (as in medieval Naxos), whereas in others, large-scale reorganisation took place (e.g. around the monastery at Samos, in Galicia).

Importantly, the OSL-PD sediment chronologies have produced evidence of large-scale land-use in periods for which no other evidence indicative of landscape exploitation survives. This is exemplified by our case studies at Gölcük (Silifke, Turkey) and Kastro Apalirou (Naxos, Greece), where braided terrace systems lie immediately adjacent to the remains of extensive, deserted settlements dated through archaeological survey to the fifth to ninth centuries AD. It was originally assumed that the partly abandoned terraces were likely contemporaneous with the settlements. The luminescence chronologies, however, demonstrate that the main periods of terrace construction and use at both sites were several hundred years later, between the eleventh and fourteenth centuries. This major episode of land use is otherwise entirely unattested: neither area has surviving medieval documentary records, surface finds of later medieval artefacts are relatively scarce and local conditions are not conducive for the preservation of pollen cores.

At certain times, terrace-building appears to have intensified, including during the mid twelfth and early sixteenth centuries AD. These trends are broadly synchronous in the five case-study areas, despite differences in terrace morphology and function. Data from climate proxies suggest that both peaks in terrace-building coincided with relatively cool periods (Xoplaki et al. Reference Xoplaki2018). Nevertheless, the relationships between climate and land use are not straightforward: climate models also suggest rainfall patterns across the region diverged significantly during these periods (Finné et al. Reference Finné, Woodbridge, Labuhn and Roberts2019). Agricultural change could have been stimulated by various other drivers, including political, economic and social factors (Haldon & Rosen Reference Haldon and Rosen2018). Shifting patterns of land tenure and local autonomy, for example, could have been important in all five case-study areas (Barton Reference Barton2010; Vionis Reference Vionis2012: 39–56). Terraces may have provided a flexible resource that enabled farmers to respond in resilient ways to different challenges.

The formation sequences of terraces, along with other archaeological earthworks, such as earth banks (Vervust et al. Reference Vervust, Kinnaird, Herring and Turner2020), can now be reconstructed in detail using OSL-PD. The ability to create fully dated sediment profiles reduces our dependence on patchy documentary and archaeological sources, and helps us to discern and understand key periods of landscape change. It also opens the possibility to link other soil-science approaches, such as sediment micromorphology, microfossil analysis and geochemistry, providing essential, diachronic detail on shifting land-use and soil management. The ability to describe and date accurately how landscapes were exploited at different times in the past means that it will be possible to understand the effects of different practices—which practices, for example, proved sustainable over long periods and which triggered environmental degradation. Such knowledge has the potential to help landscape archaeologists provide valuable scenarios for transdisciplinary debates about future policy in areas from agriculture and water management to energy and climate change.

Acknowledgements

Our thanks to colleagues for their help with fieldwork: Ollie Dempsey, Maria Duggan, Gianluca Foschi, Stelios Lekakis, Joan Lluís, Carlos Otero-Vilariño, Anna Perera, Natalia Salazar, Noemi Silva Sánchez, Marta Sancho, Lisa-Marie Shillito, Grace Turner and Chris Whittaker.

Funding statement

Funding for fieldwork and analysis has been provided by grants from the Newton Fund administered by the British Academy (AF140007 & AF160103), UK Research and Innovation (AH/P005829/1 & AH/P014453/1), the Scientific and Technological Research Council of Turkey (116K829), the European Commission (H2020 657050), Dumbarton Oaks (Washington, D.C.), Seven Pillars of Wisdom Trust (UK), Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness (HAR2012-35022) (Spain), Xunta de Galicia (2016 PG-065) (Spain).

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.15184/aqy.2020.187