Introduction

In recent decades, archaeological textile research has contributed new and important information to the understanding of European cultural history (Andersson Strand et al. Reference Andersson Strand, Frei, Gleba, Mannering, Nosch and Skals2010; Bender Jørgensen & Grömer Reference Bender Jørgensen and Grömer2013; Nosch Reference Nosch, Ruppenstein and Weilhartner2015). The development of new cross-disciplinary analytical methodologies has made a particularly important contribution. These include: the refinement of wool fibre identifications; different chemical extraction methods for the identification of organic dyestuffs; and new developments in the fields of aDNA and strontium isotope analysis (Benson et al. Reference Benson, Hattori, Taylor, Poulson and Jolie2006; Frei et al. Reference Frei, Frei, Mannering, Gleba, Nosch and Lyngstrøm2009, Reference Frei, Vanden Berghe, Frei, Mannering and Lyngstrøm2010; Vanden Berghe et al. Reference Vanden Berghe, Gleba and Mannering2009; Brandt et al. Reference Brandt, Tranekjer, Mannering, Ringgaard, Frei, Willerslev, Gleba and Gilbert2011; Gleba Reference Gleba2012; Rast-Eicher & Bender Jørgensen Reference Rast-Eicher and Bender Jørgensen2013; Frei Reference Frei2014).

Recent provenance investigations, applying new chemical protocols based on the strontium isotopic tracing system, indicate that skin and textile raw materials were traded during the Nordic Bronze Age (1700–500 BC) (Frei et al. Reference Frei, Mannering, Kristiansen, Allentoft, Wilson, Skals, Tridico, Nosch, Willerslev, Clarke and Frei2015a & Reference Frei, Mannering, Thrane, Suchowska-Ducke and Vandkildeb). The term ‘trade’ instead of ‘exchange’ is used here following terminology recently adopted for provenance analyses of Scandinavian metal artefacts and glass beads from the Nordic Bronze Age (Ling et al. Reference Ling, Stos-Gale, Grandin, Billström, Hjärthner-Holdar and Persson2014; Kristiansen & Suchowska-Ducke Reference Kristiansen and Suchowska-Ducke2015; Varberg et al. Reference Varberg, Gratuze and Kaul2015). The most recent example of wool provenance investigation is the study of the Danish Bronze Age elite female grave from Egtved, which demonstrated that the clothing was made of non-local wool (Frei et al. Reference Frei, Mannering, Kristiansen, Allentoft, Wilson, Skals, Tridico, Nosch, Willerslev, Clarke and Frei2015a). That study could, however, represent a single case of textile movement or trade in wool.

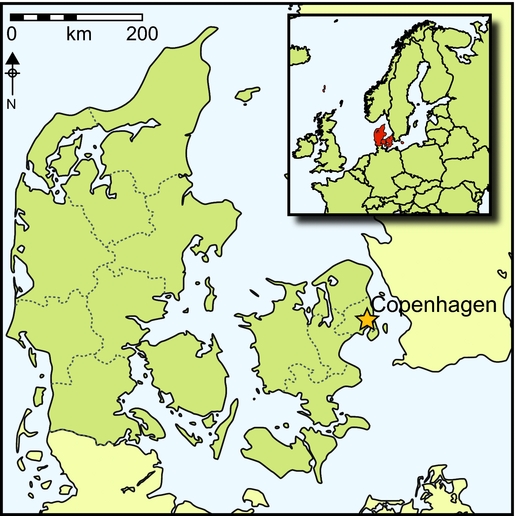

The current study aims to provide further investigations for the wool trade during the Danish Bronze Age by applying the strontium isotope tracing system to a larger number of textiles from similar contexts. The selected material comes from one of the largest collections of Bronze Age textiles in Europe (Figures 1 & 2) (Broholm & Hald Reference Broholm and Hald1940). The wool samples for the current analyses were taken mainly from burial contexts with the exception of a single hoard deposition.

Figure 1. The Early Bronze Age Borum Eshøj female, with her clothing and grave goods placed in the oak coffin (photograph: Roberto Fortuna and Kira Ursem, National Museum of Denmark).

Figure 2. The Early Bronze Age clothing and grave goods belonging to the Trindhøj male placed in the oak coffin (photograph: Roberto Fortuna and Kira Ursem, National Museum of Denmark).

Organic dye analyses were also conducted to provide information on the use of plant dyes during the Danish Bronze Age. The results of these analyses had a further purpose, as they controlled the choice of the appropriate technique for pre-treating the wool samples prior to the strontium isotope analyses (as described in Frei Reference Frei2014).

Methods and dataset

During the Nordic Early Bronze Age Periods II–III (1500–1100 BC), elite individuals were buried in oak coffins placed in man-made monumental mounds (Kristiansen & Larsson Reference Kristiansen and Larsson2005: 242, fig. 110; Randsborg & Christensen Reference Randsborg and Christensen2006). It has been estimated that more than 50000 burial mounds were raised in Denmark alone over just a few generations, evidence that supports the interpretation of the rise of a new, powerful social elite during this period (Kristiansen & Larsson Reference Kristiansen and Larsson2005: 186–250; Holst et al. Reference Holst, Rasmussen, Kristiansen and Bech2013). Waterlogging within the core of some of these burial mounds produced anoxic and acidic environments (Breuning-Madsen et al. Reference Breuning-Madsen, Holst, Rasmussen and Elberling2003), thereby, in many cases, preserving textiles and skin/leather materials.

For this wool provenance study, the authors selected some of the best-preserved textiles from the following Early Bronze Age inhumation burials (all located in western Denmark): Borum Eshøj A (dendrochronologically dated to 1351 BC); Borum Eshøj C (typologically dated to Period II); Trindhøj (dendrochronologically dated to 1347 BC); and Nybøl (dendrochronologically dated to 1266 BC) (Randsborg & Christensen Reference Randsborg and Christensen2006). To these were added the stone cist cremation burial from Hvidegaard (Goldhahn Reference Goldhahn, Berge, Jasinsko and Sognnes2012) in eastern Denmark. Typologically dated to Period III (Figure 3), this burial belongs to the group of cremation burials in mounds, a practice that became more common during Period III. The grave goods in the Hvidegaard burial included a wool textile and a small leather bag containing exotic objects, along with other items (Kaul Reference Kaul1998: 16–20).

Figure 3. Map of Europe indicating the locations of the studied textile finds: 1) Vester Doense; 2) Melhøj; 3) Muldbjerg; 4) Borum Eshøj; 5) Egtved; 6) Trindhøj; 7) Nybøl; 8) Lusehøj; 9) Haastrup; 10) Hvidegaard. The gradually shaded areas indicate regions where bioavailable strontium isotope ranges similar to those in Denmark can be expected. Regions outside these areas can be potential places of origin for non-local wool (drawing: Freerk Oldenburger, National Museum of Denmark).

During the Late Bronze Age Periods IV–VI (1100–500 BC), elite burial traditions changed from inhumations to cremations placed either in existing mounds or in smaller, newly built mounds (Thrane Reference Fokkens and Harding2013). In the latter, textiles were primarily used to wrap grave goods, or to wrap the cremated bones placed inside the urns. The items selected for analysis from cremation graves are from Lusehøj (Period V, 950–750 BC) and Haastrup (Period VI, 750–500 BC)—both located on the island of Funen (Thrane Reference Thrane1984, Reference Fokkens and Harding2013)—and from a bronze hoard with female-associated objects from Vester Doense I in western Denmark, dated to Period V (Frost Reference Frost2003).

A total of 80 organic dye analyses were performed on Danish Bronze Age textiles, following standard extraction and identification methods (Wouters Reference Wouters1985; Vanden Berghe et al. Reference Vanden Berghe, Gleba and Mannering2009). Sixty-eight of the samples were from Borum Eshøj A and C (Figure 1), Trindhøj (Figure 2) and Egtved, and from the inhumation stone cist grave from Melhøj. Ten samples came from Hvidegaard, Lusehøj (Figure 4) and Haastrup (Figure 5). Finally, two samples came from the Late Bronze Age bog hoard of Vester Doense. Samples of approximately 0.5mg of wool were taken, and the dyes were separated with a solvent mixture of water, methanol and hydrochloric acid further purified in ethyl acetate. Samples were analysed using reversed phase liquid chromatography with photo diode array detection (RP-HPLC-DAD).

Figure 4. The Late Bronze Age bronze urn from the Lusehøj male burial, which was wrapped in a wool textile. Cremated human remains within were wrapped in a nettle textile (photograph: Karin Margarita Frei, National Museum of Denmark).

Figure 5. The 2/2 twill textile from Haastrup. The black bar measures 100mm (photograph: Ulla Mannering, National Museum of Denmark).

Subsequent strontium isotope analyses were performed on a total of 32 samples of the same wool textiles as those listed above (except for Melhøj). The authors also collected five samples from the oak coffin grave at Nybøl, giving a total of 27 wool thread samples from inhumation graves from four different oak coffins, four samples from three cremation graves and one sample from a hoard. Where possible, threads from both thread directions (warp and weft) were sampled, with samples generally weighing between 10–40mg.

Following the results of dye identification analyses (HPLC), the textile samples were subjected to pre-cleaning processes, prior to dissolution. This ensured the removal of exogenous strontium (as described by Frei Reference Frei2014; Frei et al. Reference Frei, Mannering, Kristiansen, Allentoft, Wilson, Skals, Tridico, Nosch, Willerslev, Clarke and Frei2015a). The authors have successfully applied their pre-cleaning protocols to wool textiles in a large number of previous studies (described in Frei et al. Reference Frei, Frei, Mannering, Gleba, Nosch and Lyngstrøm2009), and are therefore confident in applying this methodology. This contrasts with von Holstein et al. (Reference Von Holstein, Font, Peacock, Collins and Davies2015), who were unable to recover biogenic ratios in wool samples. Finally, the pre-cleaned wool samples were subjected to strontium isotope fraction extraction following the analytical method described by Frei (Reference Frei2014) and Frei et al. (Reference Frei, Mannering, Kristiansen, Allentoft, Wilson, Skals, Tridico, Nosch, Willerslev, Clarke and Frei2015a).

Results

Results from the organic dye and the strontium isotope analyses of the Bronze Age textile samples are presented in Table 1 (below) and Table S1 (in online supplementary material). Ellagic acid was detected in 44 of the 80 samples analysed (Table S1). This molecule, which suggests the presence of tannin-rich substances in the textiles, was only found in the samples from the oak coffin graves. Considering the burial context, the presence of tannin is most probably the result of chemical migration from the oak coffins to the textiles, rather than indicating the use of a dyestuff. Indeed, no constituents were found that can be related to any dye source. Analysis of this large sample set leads us to conclude that there is no evidence for the use of organic dyes in Danish Bronze Age textiles. These results support earlier studies that have also indicated that Scandinavian Early Bronze Age textiles were not dyed (Stærmose Nielsen Reference Stærmose Nielsen1989).

Table 1. Strontium isotope results of Bronze Age wool textiles from Denmark (non-local values are indicated in bold).

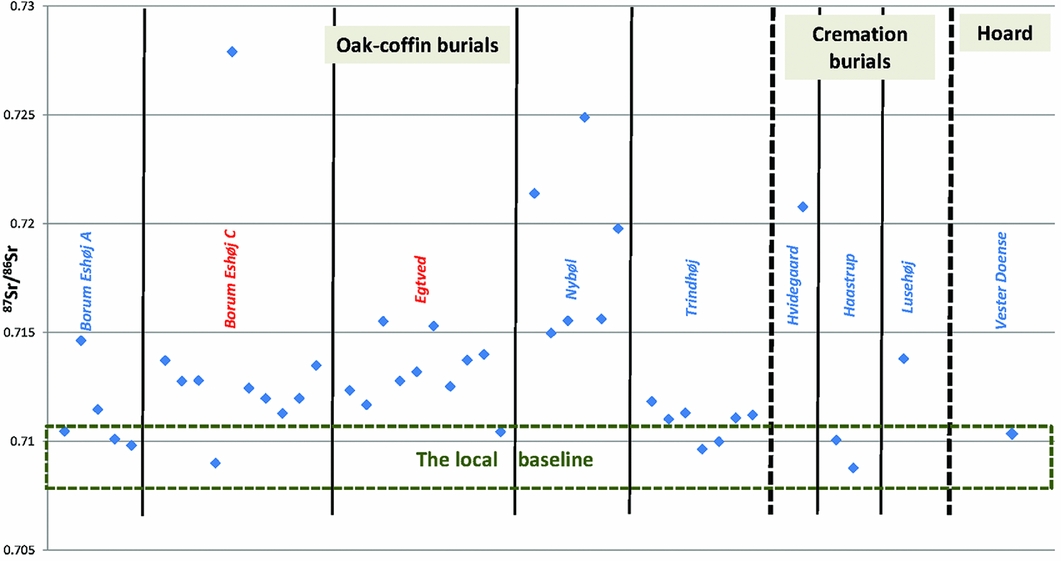

The strontium isotope results (Table 1) show a large overall variation of values, ranging from relatively low strontium isotope ratios of 87Sr/86Sr = 0.70867 (±0.00004) to high strontium isotope ratios of 87Sr/86Sr = 0.7279 (±0.00001) (Figure 6). Previous studies delineating the range of bioavailable strontium isotope compositions characteristic for Denmark (excluding the island of Bornholm in the Baltic Sea, and hereafter referred to as Denmark), have resulted in a baseline range defined by 87Sr/86Sr values of 0.708–0.711 (Frei & Frei Reference Frei and Frei2011, Reference Frei and Frei2013; Frei & Price Reference Frei and Price2012). Consequently, the results of this study suggest that 70 per cent of the wool fibres analysed came from sheep that grazed outside the geographic limits of present-day Denmark. Even though most of the wool is of non-local provenance, the distribution of local vs non-local ratios in this dataset varies from grave to grave. The textile samples from Nybøl, Hvidegaard and Lusehøj, for example, all yield evidence that they were made from non-local wool (Table 1; Figure 6), while most of the samples from Trindhøj yield a non-local provenance with the exception of wool from the cap and the belt. In contrast, most of the textiles from the Borum Eshøj A male grave seem to have been made from local wool (Table 1; Figure 6), while textiles from the Borum Eshøj C female grave consisted mostly of non-local wool—only the wool sample from the large tubular textile (a wrap-around dress) had a strontium isotopic value that falls within the local range for Denmark. Finally, wool from the Haastrup and Vester Doense textiles yielded a strontium isotopic signature falling within the local range for Denmark.

Figure 6. The strontium isotope results from the selected Bronze Age wool samples. The green rectangle shows the strontium isotopic range characteristic for Denmark (the island of Bornholm excluded). Results from female burials are marked in red, and male burials in blue.

Discussion

Textile production involves a long series of time-consuming processes, starting with the procurement and preparation of the raw materials, followed by spinning and weaving. Textiles, therefore, represent a complex châine opératoire, including different steps that might vary depending on the final product (Andersson Strand Reference Andersson Strand2012; Sofaer et al. Reference Sofaer, Bender Jørgensen, Choyke, Harding and Fokkens2013).

Wool production in Central Europe probably started with the rise of Bronze Age political economies; for example, at Szazhalombatta in Hungary, where large quantities of textile tools and sheep bones have been recovered from Bronze Age layers (Vretemark Reference Vretemark, Earle and Kristiansen2010: figs 6.4 & 6.5). Randsborg (Reference Randsborg2011) argues that, in Scandinavia, textiles were major trade items during the Nordic Bronze Age, and proposes that wool formed part of long-distance exchange networks from southern Scandinavia to the south of Europe (Randsborg Reference Randsborg2011: 92–110).

The recent study of a 16–18-year-old woman from Egtved in Jutland (whose oak coffin was dendrochronologically dated to 1370 BC) yielded complex evidence for the potential trade in wool, or wool textiles, and long-distance travels (Frei et al. Reference Frei, Mannering, Kristiansen, Allentoft, Wilson, Skals, Tridico, Nosch, Willerslev, Clarke and Frei2015a). In this case, the wool samples from the Egtved woman's entire outfit and blanket all yielded strontium isotope values indicating non-local provenance (Table 1). Only wool from a cord, probably a kind of amulet, was made of wool that might have been of local provenance (Frei et al. Reference Frei, Mannering, Kristiansen, Allentoft, Wilson, Skals, Tridico, Nosch, Willerslev, Clarke and Frei2015a). As noted above, however, Egtved's case study might represent an isolated instance of trade in wool. The present larger study sets it in context and provides a more general overview of wool provenance during the Bronze Age in Denmark. Provenance analyses of a total of 32 new wool samples from seven Danish Bronze Age graves and one hoard clearly show a high proportion of non-local wool among the textiles (Figure 6). When the ten strontium isotope textile analyses from Egtved are included (Frei et al. Reference Frei, Mannering, Kristiansen, Allentoft, Wilson, Skals, Tridico, Nosch, Willerslev, Clarke and Frei2015a), it becomes evident that more than 75 per cent of the tested wool samples are of non-local origin. Furthermore, the non-local wool samples reveal a wide range of strontium isotopic values. This indicates that the wool originated from geologically varied areas. There are potentially many areas of origin for these non-local wool samples. It is not possible at this stage, however, to determine exact areas of origin for the wool, although regions of likely origin are suggested in Figure 3 (beyond the gradually shaded areas).

These results challenge previous assumptions that Scandinavian Bronze Age textiles were, given their sometimes coarse appearance, exclusively local products, and demonstrate a hitherto unforeseen and complex trade network of raw materials that involved potentially large and geographically distant areas. This poses an important but challenging question: how was the non-local wool brought to Denmark? We propose three possible scenarios to address this: 1) raw wool or yarn was traded, but weaving took place locally (i.e. in Denmark); 2) pieces of woven textiles were traded, but were locally finished into garments; 3) garments made of non-local wool were brought by the travellers wearing them. It is important to emphasise here that one scenario does not preclude the others; the wool could have been imported through a combination of these scenarios.

The two male oak coffin burials from Trindhøj and Borum Eshøj A share several interesting features. The strontium isotope analyses of the textile samples (comprising both local and non-local wool) from these two burials yield similar datasets, with ratios representing a relatively narrow range of values (87Sr/86Sr~0.710–0.712). The only exception is the weft from the Borum Eshøj A wrap-around garment, which has a higher strontium isotope value of 87Sr/86Sr~0.715. This narrow and relatively low range of strontium isotopic values contrast with the much broader range yielded by the Nybøl samples (87Sr/86Sr~0.715–0.725), and demonstrates that these textiles were made entirely of non-local wool. Hence, the wool origin for the Nybøl textile collection seems to differ from that of the Trindhøj and Borum Eshøj A textiles, which is in agreement with previous studies (Bergerbrant et al. Reference Bergerbrant, Bender Jørgensen and Fossøy2013). It should also be mentioned that the Trindhøj and the Borum Eshøj A males were buried with distinctive piled caps, which have been suggested to indicate Bronze Age individuals of elite status (Figure 7) (Broholm & Hald Reference Broholm and Hald1940; Kristiansen & Larsson Reference Kristiansen and Larsson2005: figs 118–20). That no such cap was associated with the Nybøl male further highlights the important differences between these burials (Bergerbrant et al. Reference Bergerbrant, Bender Jørgensen and Fossøy2013). The wool from the Hvidegaard burial and sample ‘Q’ from Nybøl (Figure 8) both yielded strontium isotope signatures of >0.720, suggesting an origin in Precambrian geological terrains, such as in Sweden, Norway, Scotland, the Massif Central in France, the Bohemian Massif in Central Europe and the island of Bornholm in the Baltic Sea.

Figure 7. The Early Bronze Age Borum Eshøj A male skull and piled cap. These very special piled caps have been interpreted as a sign of the absolute Bronze Age male elite (photograph: Karin Margarita Frei, National Museum of Denmark).

Figure 8. Textile (Q type C) from the Early Bronze Age Nybøl male burial. The black bar measures 100mm (photograph: Roberto Fortuna, National Museum of Denmark).

Results demonstrate that the textiles from the two female oak coffin burials at Egtved and Borum Eshøj C consisted of textiles of which 90 per cent were made of non-local wool. Recent provenance investigations of the Egtved woman (Frei et al. Reference Frei, Mannering, Kristiansen, Allentoft, Wilson, Skals, Tridico, Nosch, Willerslev, Clarke and Frei2015a) have demonstrated that she did not originate from Denmark (the island of Bornholm excluded), and it is tempting to suggest that the Borum Eshøj C female could also be of non-local origin. Subject to future confirmation through isotopic analysis, this could indicate that exogamy was more widespread than previously assumed. Our investigation of the textiles associated with this grave reveals the broadest set of strontium isotopic signatures within this study, ranging from 87Sr/86Sr~0.709–0.728, and the highest strontium isotopic value within the entire dataset. This clearly shows that the wool used in the production of the garments was collected from diverse, potentially very distant, geographic areas. Borum Eshøj C wool samples with the highest isotopic values probably originated from similar geological areas as the textiles associated with the Hvidegaard and Nybøl graves. Samples with lower isotopic values may have originated from a variety of other areas.

Wool from the Late Bronze Age cremation burials at Lusehøj and Haastrup have different strontium isotopic values, despite the fact that they were associated with high-status males buried in the same area. The Lusehøj wool sample has a non-local value, as did the previously analysed nettle textile belonging to the same grave (Bergfjord et al. Reference Bergfjord, Mannering, Frei, Gleba, Scharff, Skals, Heinemeier, Nosch and Holst2012), whereas the Haastrup textile has strontium isotopic values falling within the Danish strontium isotopic bioavailable range. The Haastrup textile represents the first twill textile from a Danish prehistoric context, and is unique in its thread count, which is much higher than seen in Bronze Age tabby textiles (Bender Jørgensen Reference Bender Jørgensen1986). Interpretation of a non-local origin for this textile would be understandable, given the current knowledge of contemporaneous textile-manufacturing technology. This isotopic research, however, suggests that the textile represents a forerunner to an emerging Scandinavian Early Iron Age textile technology, which was based on the introduction of the twill weave (Figure 5).

New evidence presented by our strontium isotope research demonstrates that large quantities of non-local wool were used by Danish society during the Nordic Bronze Age. This challenges previous interpretations of wool-textile production as a strictly local, home-based craft.

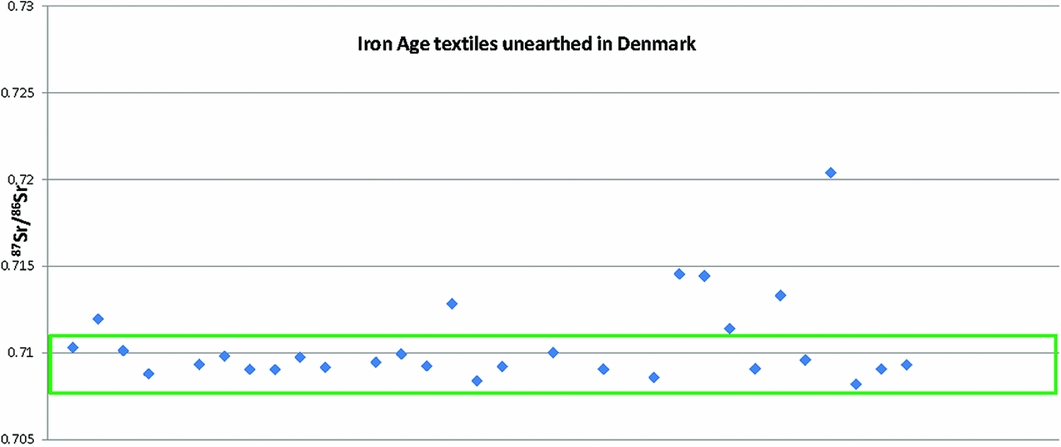

This new interpretation is further supported by the small quantity of sheep bones recovered from Early Bronze Age settlements. Sheep bones become more common towards the end of the Bronze Age, suggesting the development of a strong local wool economy (Hedeager & Kristiansen Reference Hedeager, Kristiansen and Bjørn1988: 86). If all available data from the authors’ previous research on Early Iron Age Danish textiles are compiled (Figure 9; Table S2 in online supplementary material), there emerges a clear contrast in the proportion of non-local and local wools compared to the Bronze Age: at least 75 per cent of Danish Bronze Age wool textiles were of non-local origin, compared to 25 per cent in the Early Iron Age.

Figure 9. The strontium isotope results from wool samples from Early Iron Age bog textiles from Denmark corresponding to Table S2. The green rectangle shows the strontium isotopic range characteristic for Denmark (the island of Bornholm excluded).

A similar pattern can be observed in the use of organic dyes. While Vanden Berghe et al. (Reference Vanden Berghe, Gleba and Mannering2009) concluded that the majority of all Danish Pre-Roman Iron Age (500–1 BC) bog textiles contained traces of plant dyes, our dyestuff analysis revealed no evidence for the use of dyes in the Nordic Bronze Age. The lack of trace evidence of organic dye use may have been influenced by sample age and varied taphonomic conditions. The lack of dyestuff traces in the Late Bronze Age hoard from Vester Doense I (Table S1), which was preserved in a similar bog environment as the Pre-Roman Iron Age textiles, nevertheless supports the hypothesis that no dyestuffs were used in Nordic Bronze Age textile production.

The new results provided by the wool provenance investigations suggest that some of the wool garments were brought to Denmark as finished outfits, such as in the case of the Egtved woman. Archaeological evidence shows that the Danish Bronze Age society was connected through a web of political alliances that ensured safe travel and used trade caravans as is shown, for example, by the distribution of octagonally hilted swords in relation to local groups (Kristiansen & Larsson Reference Kristiansen and Larsson2005: fig. 107). We hypothesise that wool was also traded as part of these connections.

Wool fibre investigations of textiles from sites in Italy and Austria (dating from the Middle Bronze Age to the Roman period) have revealed an important change in textile production, from the use of primitive to more uniform sheep fleeces with no kemps (Gleba Reference Gleba2012). Furthermore, in the southern European Iron Age, different sheep breeds seemed to have coexisted (Gleba Reference Gleba2012). A wool fibre study of Bronze Age textiles and fleeces from Austria (Hallstatt), Bosnia-Hercegovina, Norway and Sweden also suggests that different sheep breeds existed in Europe at this time (Rast-Eicher & Bender Jørgensen Reference Rast-Eicher and Bender Jørgensen2013); and an ongoing study of Danish Bronze Age textiles supports this assumption (Skals & Mannering Reference Skals and Mannering2014).

When comparison is made between the provenance of the Danish Bronze Age wool and that of other materials, a common pattern suggestive of long-distance contacts emerges. For example, recent elemental and lead isotope analyses of over 70 metal artefacts found in Sweden dating to the Nordic Bronze Age (Ling et al. Reference Ling, Stos-Gale, Grandin, Billström, Hjärthner-Holdar and Persson2014) revealed that the copper within these artefacts seems to have originated non-locally. Ling et al. (Reference Ling, Stos-Gale, Grandin, Billström, Hjärthner-Holdar and Persson2014) suggest several potential sources for the copper ore, including North Tyrol, the Iberian Peninsula and Sardinia. Similarly, recent chemical analyses of 23 Nordic Bronze Age glass beads discovered in Denmark revealed long-distance trade with Mesopotamia and Egypt (Varberg et al. Reference Varberg, Gratuze and Kaul2015). This supports the hypothesis that wool may also have been a commodity that formed part of complex and extended trade networks. Further research is, however, required to evaluate and explain the Nordic Bronze Age wool trade in more detail.

Conclusion

The results of the strontium isotope analyses presented here suggest that production of wool for the Nordic Bronze Age elite took place primarily outside the geographic limits of present-day Denmark (with the exception of the island of Bornholm). Furthermore, there seem to have been several production areas, geographically distant from each other—potentially several hundreds of kilometres apart. This is reflected by the wide range of strontium isotopic values encountered, which indicate sheep-grazing on geologically different areas. In the Nordic Bronze Age at least 75 per cent of the tested textiles were made of non-local wool, whereas this figure falls to 25 per cent in the Early Iron Age.

No evidence has so far been found for the use of organic dyestuffs during the Bronze Age in Denmark. The tannin detected in four oak coffin burials most probably results from the migration of tannin from the wooden coffins to the textiles, rather than being related to any dyeing process. It seems probable that organic dyes were introduced simultaneously with a reduction in the intensity of the wool trade, and in combination with the emerging Early Iron Age technology and fashion.

Other studies of European wool have shown complexity in wool production and trade, but it remains difficult to determine how this trade took place (i.e. as whole textiles or as raw materials only). Trade routes are also difficult to define, although future wool fibre and sheep bone analyses (e.g. strontium isotope and aDNA) may further our current understanding.

In conclusion, this study shows that during the Nordic Bronze Age, long-distance trade of wool and/or wool textiles was complex, widespread and significant, and potentially as important as the trade of metals. Complex results are rarely supported by simple explanations; these new data provide an additional layer of complexity to our current understanding of Nordic Bronze Age society.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Robert Frei for providing access and assistance at the isotope laboratory facilities at the Danish Center for Isotope Geology, University of Copenhagen, as well as to Cristina Jensen, Toby Leeper and Toni Larsen for help in the laboratory. We also wish to thank Irene Skals for her help in sampling the textiles, and Marie-Christine Maquoi from the textile laboratory at KIK-IRPA in Brussels, for her assistance in the laboratory. Furthermore, we wish to express our appreciation to Per Kristian Madsen, Marie- Louise Nosch, Poul Otto Nielsen, Peter Rasmussen and Flemming Kaul for comments and for providing access to the archaeological material. Finally, we wish to thank the three reviewers for their important constructive comments, which helped to improve the manuscript. This research has been possible through the support of The Danish National Research Foundation (DNRF 64), The ERC Advanced Grant agreement 269442 (The Rise) and the Carlsberg Foundation Grant CF-15 0878 (Tales of Bronze Age Women) to author KMF.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.15184/aqy.2017.64