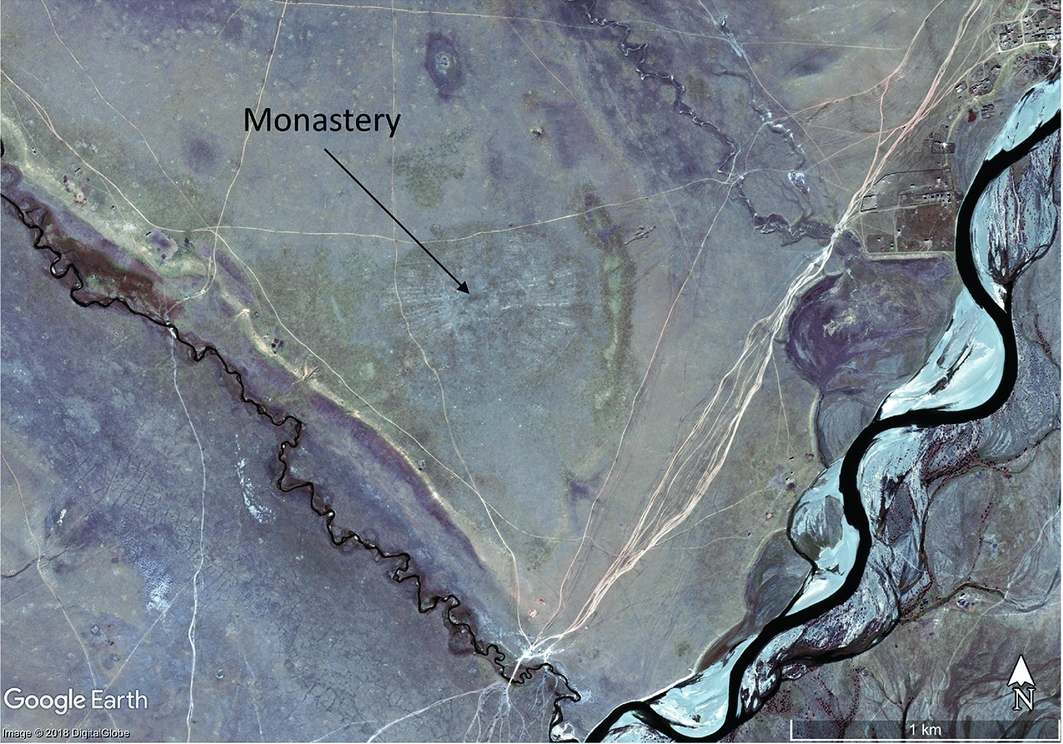

In 2012, satellite images appeared online that revealed the remains of a circular and well-planned archaeological site (Figure 1) on the west bank of the Kherlen River, 25km south of Mongonmorit soum, Mongolia (48 0.806N/108 29.833E). Since 2008, a joint University of Bristol/National University of Mongolia expedition has been studying the archaeology of the Upper Kherlen Valley, and this feature was of immediate interest (Horton et al. Reference Horton, Dashtseveg and Myagmar2012). Radiating buildings from a number of central structures were visible in the light snow cover in this image. Following a GPS and magnetometer survey in 2014 (Horton et al. Reference Horton, Erdene, Pecchia and Parkes2015), we realised that the site was ideal for testing ground-penetrating radar (GPR) in the Mongolian grasslands. In 2016, we used UAV survey to capture a detailed map of the site, and then employed GPR to investigate specific features.

Figure 1. Google Earth/DigitalGlobe image showing the Dzuun Khuree monastery on the west bank of the Kherlen River, taken 10 October 2012.

The site is known locally as Dzuun Khuree, Kherlen golyn zuun khuree, Khoegshin Khuree and Uvgun khuree (Maidar Reference Maidar1972: 100; Rinchen & Maidar Reference Rinchen and Maidar1979: 56). The features captured in the UAV imagery are undoubtedly the remains of a former monastery. This was mapped by Klyagina-Kondratiyeva (Reference Klyagina-Kondratiyeva, Chuluun and Yusupova2013: 182) in 1929, and recently included in the ‘Documentation of Mongolian Monasteries’ project. The monastery belonged to the ‘yellow robe’ (Gelugpa) sect of Buddhism and was located below the sacred Togos Kharkhan mountain. It had around 1200 monks and was one of the largest religious and trade centres in central Mongolia, the monastic city of the second Bodg Jebtsundamba, Luvsandambiydonmi (1724–1757) and renowned as one of the five cherished places of Undur Gegeen Zanabazar (1635–1723) (Tsedendamba Reference Tsedendamba2009). Traditions place its foundation in either 1691 (DOMM Study 2004) or 1701, while Pozdneev (Reference Pozdneev, Krueger, Shaw and Plank1971: 303), citing the Erdeni-yin Erike chronicle, claimed that it was founded in year 50 of Enkh-Amgalan Khan (1711). There are, however, reasons to believe that the monastery may be older than these conflicting records suggest—a view also shared by Pozdneev, who visited the working monastery in 1896. The monastery was suppressed in 1937, the buildings destroyed and the monks dispersed.

Description of the site

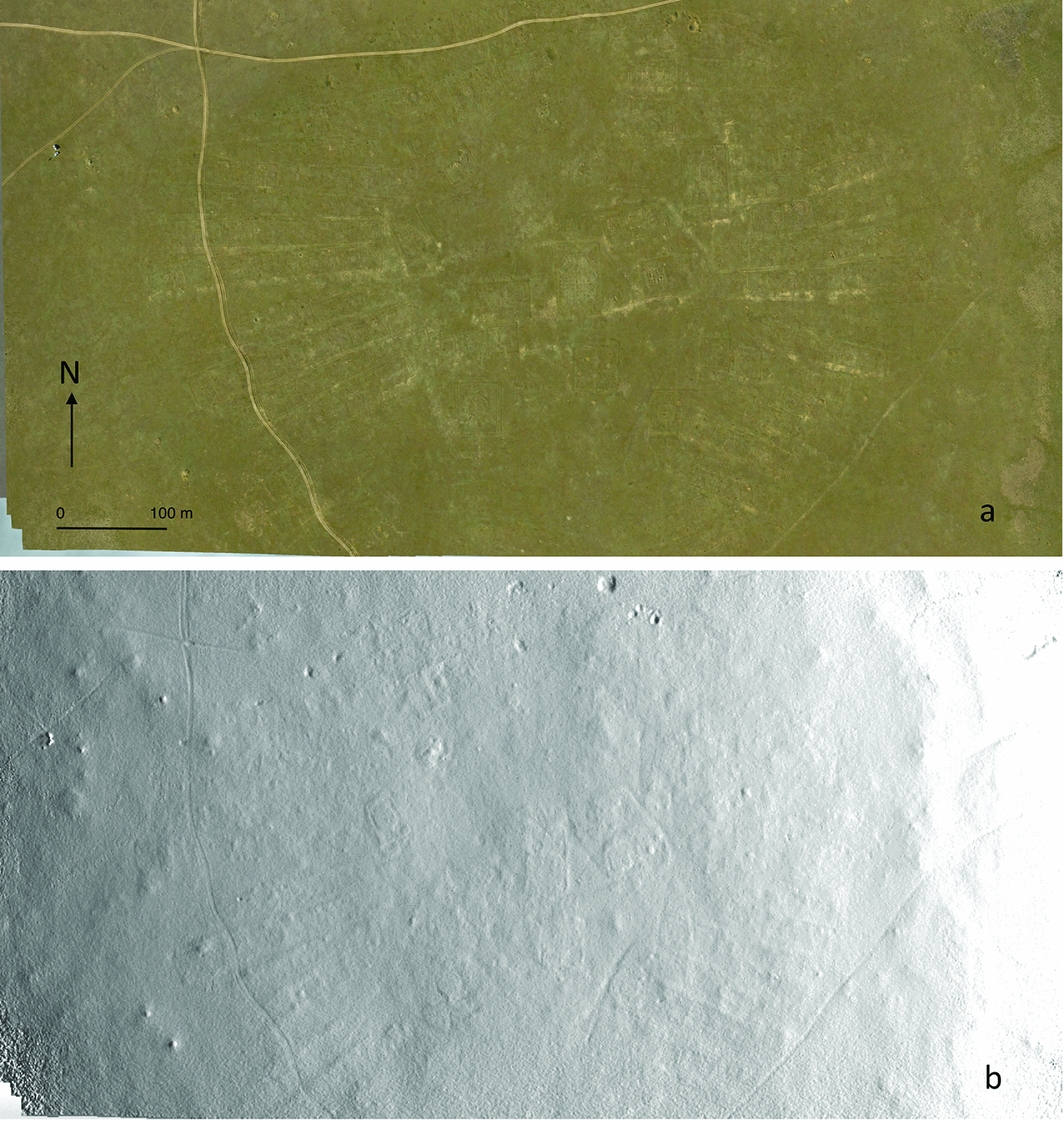

The site is located on a flat alluvial terrace between the Kherlen River and two smaller streams. On the surface there is very little to see, beyond discoloured grass, and low mounds marking the position of 28 stupas surrounding the site. The UAV survey was conducted with a DJI Phantom 3 Professional, and the orthomosaic (Figure 2a) processed using the drone deploy platform (http://dronedeploy.com). Elevation and hillshade imagery from the digital elevation model (Figure 2b) were also generated from high-resolution images (2ins/pixel). From this data and the ground surveys, a detailed and accurate plan was compiled (Figure 3). The monastery covers an oval area of 750 × 600m. In the centre, there are 17 temples or religious colleges, while to the east and west are 24 radiating aimags (monastic dormitories), each sub-divided into individual cells that housed traditional ghers (circular tents).

Figure 2. A) Dzuun Khuree UAV orthomosaic photograph; B) hillshade model of monastic site. Survey performed in 2016 (credit: authors).

Figure 3. Plan of the Dzuun Khuree monastic site, compiled from UAV imagery and on-site survey, 2014–2016 (drawn by Vito Pecchia).

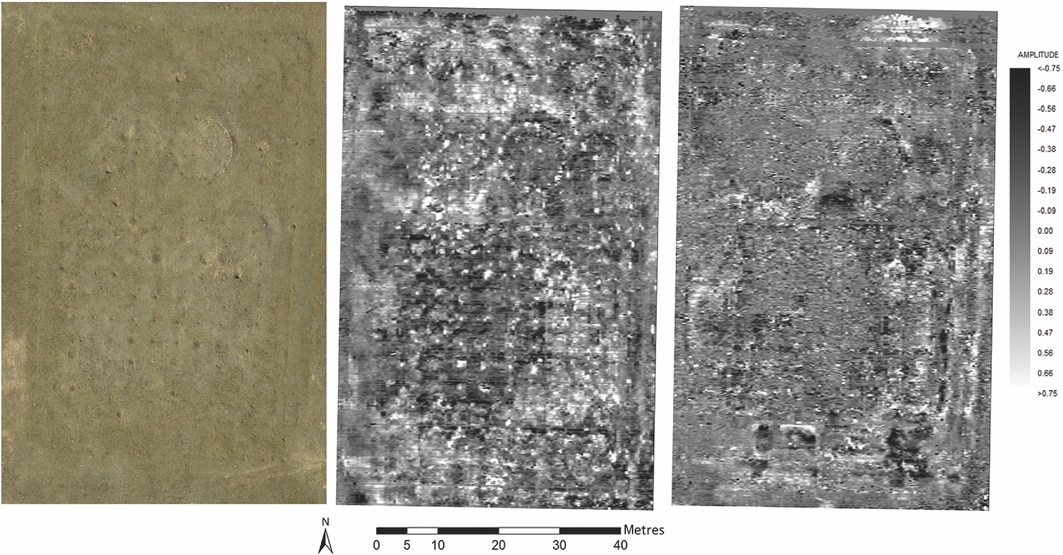

Between the temples and the aimags is a path that may represent a processional route around the central precinct. There is a central axis through the site that runs east to west, along with north and south entrances. The temples have traces of internal structures laid out with small stones, including circles and squares. These could have been to demarcate gher temples. At least three temples also contained a grid of timber posts that supported a floor and a timber superstructure. The most impressive, temple five, has a grid of 9 × 9 posts, with three circles marked out to the north, representing small ghers within the temple enclosure. The walls of each temple were probably of timber construction, built on slightly raised banks that might have formed the base of earlier mud-brick walls. We conducted GPR surveys over several of the temples. Temple five was the most informative (Figure 4), with data enabling an estimate for posthole depth of around 0.8m, the location of additional gher structures and the suggestion of sub-features below two of the gher enclosures. Similar anomalies were also found below other gher temples.

Figure 4. Temple five, UAV image and ground-penetrating radar time-slice image at 1ns and 4ns (approximately 0.2m and 0.8m depth at a velocity of 1.5m/ns) (credit: authors).

A number of gravel mounds surrounded the site—mostly along the north and west sides—measuring approximately 8m in diameter and up to 1.5m high. Some contained both fired red and grey mud-bricks, and stone slabs. Although most were heavily robbed, 28 could be recognised as stupa bases. Several also contained broken terracotta plaques (Figure 5) of a particular quality and form associated with the Zanabazar revival of the seventeenth to nineteenth centuries (Berger & Bartholomew Reference Berger and Bartholomew1995: 304). On the eastern side of the site was a tree shrine (Figure 6) with a ring of stones and a single step. While the veneration of trees is common in Buddhism, it is unusual in the treeless Mongolian landscape.

Figure 5. Terracotta plaques from disturbed context of stupa two, probably seventeenth century (Zanabazar period); Buddha in meditation, in Single Lotus pose (photograph by Mark Horton).

Figure 6. Remains of a tree shrine, with remaining stump and stones used to mark the site, facing north-east (photograph by Mark Horton).

Discussion

The Dzuun Khuree monastery is also unusual in its circular form, with its large number of central temples and radiating aimags, and may reflect the plan of secular camps (or orda). Most Mongolian monasteries have a rectilinear plan, the only other known circular examples being Ikh Khuree and the adjacent—and still surviving—Gandan monastery in Ulaanbaatar. Both are recorded on a 1913–1915 plan, now in the Zanabazar Museum. Ikh Khuree, known then as Urgu, was founded in c. 1639, and moved on multiple occasions before settling at Ulaanbaatar in 1778 (Berger Reference Berger, Berger and Bartholomew1995: 66). Gandan was founded in 1809. Dzuun Khuree may pre-date both these. Another clue that it may be earlier is the grid of posts, found in at least three of the temples that supported the floor and superstructure. This arrangement is recorded, for example, in the thirteenth-century ‘Great Hall’ temple at Karakorum (Franken Reference Franken2015) and in wider Buddhist architecture in Japan and China. The possibility that the monastery might belong to the Mongol period, therefore, should not be wholly discounted.