Introduction

In cities throughout the ancient Roman world, the tavern, known in Latin by various terms such as tabernae, cauponae and popinae, was a vital social institution, functioning at once as an important source of meals, as well as a public space for social interaction (Kleberg Reference Kleberg1957; Monteix Reference Monteix2010). In particular, the importance of taverns seems to have often been linked to the presence of artisans, labourers and other workers within urban society who did not always produce their own food, but instead also relied on taverns and markets for procuring daily sustenance. Despite the social importance of these ancient institutions, defining what exactly constitutes a tavern, and then in turn identifying archaeologically the physical characteristics shared by all taverns, can hardly be said to be straightforward. This is especially the case given the plethora of ancient terms that are known; there was clearly no universal meaning for ‘tavern’ across the Empire. For the purposes of this article, a ‘tavern’ is defined as an institution providing food and drink to clients through monetary exchange. The existence of a tavern thus implies the presence of an economy based upon specialised artisan production, rather than simply subsistence production at the domestic level, as well as the commodification of food resources and, by extension, the commodification of labour.

To date, very few taverns have been identified archaeologically in places such as Roman Gaul, perhaps in part due to the difficulty of distinguishing between taverns and other social institutions based upon their material remains (see Badan et al. Reference Badan, Brun, Congès and Baudat1997; Poux & Pranyies Reference Poux and Pranyies2009 for structures interpreted as taverns in Gaul; and Barberan et al. Reference Barberan, Bardot-Cambot, Gafa, Lemaire, Malignas, Raux, Renaud and Silvéréano2012 for evidence of a market). In a recent review of the archaeological evidence for taverns from the Roman provinces of Belgian Gaul and Upper and Lower Germania, Demarolle and Petit (Reference Demarolle, Petit and Bedon2011: 306–13) have outlined a series of criteria for identifying these structures in the archaeological record, including: the concentration of a large number of ovens (rather than a single oven per domestic unit); the storage of food and other goods well beyond the needs of a single family; the concentration of millstones for grinding grain into flour; an over-representation in the ceramic assemblages of drinking vessels; and the presence of cuts of meat for large numbers of people.

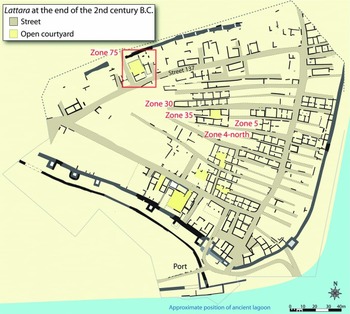

In this light, the recent discovery at the excavations of the Celtic settlement of Lattara (modern Lattes), in Mediterranean France, of a large communal structure corresponding to these characteristics, represents an unusual find. In zone 75 of the excavations (Figure 1), the authors uncovered the remains of a large structure, dating to 125–75 BC, that probably functioned as a kind of public space for feeding large numbers of people, and which has been interpreted as some form of early tavern. The appearance of this ‘tavern’ at Lattara probably corresponded with significant socio-economic changes occurring in the local society after the Roman conquest of the region during 125–121 BC. These changes included a shift from a subsistence economy to one with greater artisan production (above that of a domestic level) and an increase in the monetisation of economic exchange.

Figure 1. Map of the site of Lattara (modern Lattes) (drawn by Lattes excavations, modified by Benjamin Luley).

Context

During the Iron Age (750–125 BC), large parts of Mediterranean France were inhabited by peoples speaking a Celtic language. These Celtic peoples, grouped together into densely settled, fortified sites from the sixth century BC onwards, engaged in important commercial trading relations with Etruscan, Massaliote Greek and Italic merchants. The region was conquered by the Roman Republic in a series of campaigns between 125–121 BC, and incorporated into the province of Gallia Transalpina, later renamed Gallia Narbonensis under Caesar Augustus. The site of ancient Lattara, which was an important centre of trade during the Iron Age and early Roman period, is today located just to the south of the modern town of Lattes in the French département of Hérault in the region of Languedoc-Roussillon. The settlement was located at a strategic point where, in ancient times, the Lez River flowed into a shallow lagoon bordering the Mediterranean. From around 500 BC to the gradual abandonment of the site in the second century AD, Lattara was a thriving port of trade and densely occupied settlement (Figure 1) (Py Reference Py2009). The settlement itself consisted of long rows of stone-and-mud-brick rooms separated by narrow streets and enclosed by ramparts reinforced with towers. By the second century BC, Lattara had expanded well beyond the 3.5ha enclosed by the ramparts to cover an area of approximately 11–12ha; relatively little is known about the settlement located beyond these ramparts (Py Reference Py2009: 100). Although the architecture and urban layout remained largely unchanged immediately following the Roman conquest, the walls of the town and the traditional blocks of small houses were demolished after around 50 BC, and the population began to spread out beyond the traditional limits of the settlement in larger, courtyard-style houses.

During the Iron Age, it appears that food production at Lattara was largely conducted at a domestic level, based upon the even distribution of single bread ovens and grinding mills throughout the settlement (Py Reference Py and Py1992a, Reference Py and Py1992b). Although some craft specialisation was present at Lattara during the Iron Age, there is little evidence to suggest that this was anything more than the work of part-time specialists, with most families probably spending a great deal of time growing crops and herding animals in the fields beyond the walls of the settlement (Py Reference Py2009: 280–81). At the same time, there is little evidence for a monetised or market-based economy before the first century BC (Py Reference Py2006; Luley Reference Luley2008).

By contrast, with the imposition of Roman rule in the province at the end of the second century BC, there was a significant increase in trade and a centralisation of the production of various local commodities for export, meaning that more and more people were probably engaged primarily in activities other than the growing of their own food. Additionally, small-and medium-sized bronze coins issued from the Greek colony of Massalia became increasingly common at Lattara between 125 and 75 BC, and there is good evidence for at least partial monetisation of the economy by the end of the first century BC (Py Reference Py2006). For example, a bakery, replete with a large bread oven and a grinding mill, probably existed in zone 5 at Lattara for the period 50–25 BC (Py Reference Py and Py1992a: 228–29; Py Reference Py and Py1992b: 277–78; Sternberg Reference Sternberg and Garcia1994: 85–89). Within the floor layers of this bakery, 19 small coins were uncovered, seemingly suggesting that by this date at the latest, food resources had become at least partially commoditised (Luley Reference Luley2008: 184–88). Furthermore, starting in the first century BC, increasingly more of the agricultural land around settlements such as Lattara was being exploited by large villas for growing grapes to supply large-scale wine production (Buffat & Pellecuer Reference Buffat and Pellecuer2001). Lastly, throughout this period, the Roman Republic rewarded Roman veterans and colonists with land in a series of centuriations (see Mauné Reference Mauné2000), probably alienating some, if not many, native Celts from their traditional agricultural lands, and perhaps forcing them to sell their labour force. Thus, by the first century BC, the economic conditions at Lattara would have probably encouraged the development of institutions for feeding artisans and labourers specialising in the production of commodities that were not directly related to subsistence.

The archaeological evidence

The possible ‘tavern’ was discovered during excavation of occupation levels dating to the second and first centuries BC in zone 75 (Figure 2). The structure was strategically located at the intersection of two important streets of the settlement, as well as at one of the entrances to the town in the northern ramparts. For the period c. 125–75 BC (phase 75C2), a relatively large complex of rooms occupied zone 75, oriented around a central courtyard. This structure continued to be occupied between 75 and 50 BC (phase C1), although it no longer appears to have been specifically used as a tavern. After 50 BC, the entire courtyard structure was torn down and a number of public buildings were erected in its place.

Figure 2. Map of the excavations of zone 75 at Lattara for the end of the Iron Age and beginning of the Roman period.

For the period c. 125–75 BC, the structure occupying zone 75 consisted of at least two wings arranged to the east and south of a large central courtyard paved with river pebbles, which was separated from the street to the west by a stone-and-mud-brick wall (Figure 3). A relatively large gateway in this wall allowed access from the street into the courtyard. The southern wing of this complex consisted of a single room: sector 6. The eastern wing consisted of two rooms: sector 3, as well as traces of a room just to the north. Unfortunately, the remains of the northern half of the courtyard, as well as most of the room to the north of sector 3, have been lost due to ploughing in the twentieth century. Archaeologists have, however, uncovered a trench that almost certainly traces the outlines of stone walls delimiting the northern half of the courtyard. The stones from these walls were later taken away for reuse in later structures. Doorways in both the northern wall of sector 6 and the western wall of sector 3 allowed circulation between the courtyard and these two rooms, suggesting that the entire complex functioned together during this period. As was typical for Lattara (de Chazelles Reference de Chazelles and Py1996), and more generally for Mediterranean France in the Iron Age, the architecture of the different rooms consisted of dry limestone foundations, which provided a base for packed earthen walls. All of the rooms in zone 75 also had simple, packed earthen floors. The orientation of sectors 3 and 6 around a central courtyard is not entirely unusual for the Iron Age occupation at Lattara; several structures consisting of rooms oriented around a central courtyard, referred to as ‘courtyard houses’ (maisons à cours), have been found at the site for the period between the third and late second centuries BC (Dietler et al. Reference Dietler, Kohn, Moya, Garra and Rivalan2008). The specialised functions of sectors 3 and 6 do suggest, however, that zone 75 may have been more than simply a domestic space during this period.

Figure 3. Aerial view of the excavations of the ‘tavern’ from zone 75 (photograph by Séverine Sanz).

Sector 6

In sector 6, for the period 125–75 BC, excavations revealed three large, bell-shaped ovens in a row along the presumed eastern wall of the room, as well as a row of three stone bases along the western wall of the room, which were probably used for grinding flour(Figure 4).

Figure 4. View from the east of sector 6 (photograph by Benjamin Luley).

The three ovens were round and consisted of an inner wall of reddish, fired clay, surrounded on the outside by a thick layer of ochre-coloured clay (Figure 5). Although only the lower portions were preserved, and based on ethnographic comparisons, the ovens were probably dome-shaped, with a large opening in the top. Bell-shaped ovens such as those found in sector 6 were common at Lattara in earlier centuries, as well as for Iron Age Mediterranean France more generally (Py Reference Py1990: 434–37, 688–89; Reference Py and Py1992b). In ancient times, these ovens were referred to as a clibanus among the Romans, and as a kribanos by the ancient Greeks. This type of oven is still common in parts of North Africa and the Middle East today, and is often referred to as a tabouna, tannur or tandir (Dupaigne Reference Dupaigne1999; Luley Reference Luley2014: 45). Such an oven is used for baking unleavened flatbread, either by sticking the dough on the inside of the oven, or, in some cases, by baking the bread in a flat dish placed over the mouth of the oven.

Figure 5. View from the south-west of the oven FR75146, showing the fill of ash and collapsed walls from the oven; inset showing modern tabouna from Souidat, Tunisia (photograph by Benjamin Luley).

The stone bases, which stood 16–24cm above the floor, were built of unmortared limestone blocks, arranged in a circular form (Figure 6). Based upon other examples from Lattara and elsewhere in the region, they most probably functioned as a support for a millstone used for grinding flour (Py Reference Py and Py1992a: 223–27).

Figure 6. View from the east of the three stone bases for grinding flour; the dimensions from left to right are: 80 × 62 × 16cm; 72 × 74 × 20cm; 82 × 80 × 12 (minimum)/24cm (maximum); for the base on the right, the diameter of the inner circle, where the millstone was probably placed, is 42cm (photograph by Benjamin Luley).

Although two other examples exist of ovens being associated with bases for millstones (Py Reference Py and Py1992a: 224; Reference Py and Py1992b: 261, 264–65, 273–74), sector 6 of zone 75 is unique with regard to the scale of flour grinding and flatbread baking. Before the first century BC at Lattara, almost all of these bread ovens were found in domestic contexts, with one oven per domestic space, rather than several grouped together in a specialised workshop (Py Reference Py and Py1992b). Other than zone 75, the only other case where ovens were grouped together was from block 4-south, for the period 300–250 BC. Here, three ovens were built into an earthen bench along a wall, and with a stone base nearby, which was probably used for a millstone, suggesting perhaps a partial specialisation in bread baking (Py Reference Py and Py1992b: 273; Lebeaupin Reference Lebeaupin and Garcia1994: 65–66). In this case, however, all three ovens were small, with each measuring approximately 50cm in diameter. By contrast, the ovens from zone 75 are quite large, measuring 121, 123 and 83cm in diameter. Based upon both the size and number of mills and bread ovens, sector 6 was clearly used for producing flatbread well beyond the needs of a single nuclear family.

Sector 3

Compared with other rooms at Lattara for the same period, sector 3 is noteworthy for the presence of earthen benches running along most of the walls of the room. Although little remained of these benches, their location can be reconstructed through a border of river pebbles in a mixture of orange sandy material running along almost all the walls of the room (Figure 7). The sole exception to this, in both cases, was along the northern part of the western wall and most of the northern wall, precisely at the placement of doorways. This border of river pebbles and orange sand probably provided a level base for the packed earth benches in accordance with other examples from Lattara (de Chazelles Reference de Chazelles and Py1996: 310–12; Py Reference Py2009: 202–203). A large rectangular hearth of fired clay was present in the middle of the northern half of the room. Mud-brick benches built along parts of interior walls are certainly not uncommon at Lattara, and would have served many functions. The presence of benches along all sides of the room in a U-shape is, however, much rarer. Only three other examples of this kind of room are known from Lattara, all dating to the third century BC (de Chazelles Reference de Chazelles and Py1996: 310). In all of these cases, archaeologists have identified these rooms as dining halls. More specifically, the presence of three benches, one along each wall so as to form a U-shape, bears a striking similarity with the Roman triclinium. In the Roman world, a triclinium was a dining hall, with couches or benches situated along three sides of the room, allowing diners (ideally three per bench) to recline while dining (Dunabin Reference Dunabin and Slater1991). The fact that the floor in this room was relatively clean of debris, such as ash, charcoal, animal bones and had only a low number of very small ceramic fragments found lying flat on the surface of the floor, reinforces the idea that sector 3 was indeed a dining hall. Interestingly, no other examples of this kind of room have been found at Lattara from the second and first centuries BC.

Figure 7. View from the south of sector 3 (photograph by Benjamin Luley).

Interpretation

In summary then, for the period 125–75 BC, sector 6 of zone 75 appears to have been some kind of a bakery, producing flatbread well beyond the needs of a single nuclear family, while sector 3 appears to have functioned as a dining hall. What is striking about zone 75 for this time period is that each room had a clearly defined function. Even for the second and first halves of the first century BC, the degree of specialisation of the different rooms within any given domestic block at Lattara was limited (Py Reference Py and Py1996; Reference Py2009: 108–111, 135–38). For example, zones 4-north, 5, 30 and 35 (all of which were contemporary with the courtyard structure in zone 75) consisted of long rows of connected single rooms, separated by narrow streets (Py & Lopez Reference Py, Lopez and Py1990; Py Reference Py2004). While the general function of the room can be discerned in some cases, such as cooking and storage vs dining, socialising and sleeping, these rooms often appear to have been multi-functional.

The original hypothesis of the authors was that sector 6 perhaps functioned as a specialised bakery, intended for producing flatbread on a large scale. As mentioned above, one bakery is known from zone 5 at Lattara for the period 50–25BC. While this bakery was seemingly not associated with any other structures, sectors 3 and 6 clearly functioned together within the same building: both rooms opened out onto the central courtyard, and the level of river pebbles in the courtyard was probably contemporary with their floors. One possibility, of course, is that the courtyard (sector 3) and sector 6 were both part of a large house belonging to a wealthy baker, perhaps similar to the owner of the luxurious domus in Pompeii, known as the House of the Chaste Lovers, which had, among other rooms, a large bakery and a triclinium (Urbanus Reference Urbanus2010). This in itself would be quite exceptional, as evidence for a rigid socio-economic hierarchy at Lattara throughout the Iron Age is quite lacking (Py Reference Py2009: 333). No rooms for sleeping have been found at zone 75, although these could admittedly have been either part of an upper storey, leaving little trace in the archaeological record, or to the north of the courtyard, where preservation from this period has been poor. More importantly, however, there is nothing ostentatious about the architecture of zone 75; no decorative elements have been found to suggest an elite residence, as, for example, with the Hellenistic courtyard houses from the site of Glanum in Western Provence, which also date to the second and first centuries BC.

An alternative hypothesis is that zone 75 was not the ‘private’ residence of a specific family, but was perhaps rather a ‘public’ space where relatively large numbers of people could gather and eat together communally. Furthermore, the faunal and ceramic data certainly seem to support this interpretation. It should be pointed out that while flatbread was quite obviously an important food produced in sector 6, it was also, apparently, not the only food cooked in the room. A large number of fish and animal bones were found strewn across the floor, especially around the doorway, as well as in the layers of ash filling the three ovens. These bones correspond with the remains typically associated with preparing and cooking meals. For example, with the fish bones from the floor layers of sector 6, there is an over-representation of bones from the head of the fish, as well as scales, suggesting that the fish were fileted and prepared here. By contrast, the floor level of sector 3 produced mostly fish vertebrae, something associated with consumption rather than preparation, and that again indicates that this room functioned as a dining hall. Despite being normally associated with flatbread, archaeological and ethnographical examples attest to the fact that the three bell-shaped ovens can be used for other purposes as well (Py Reference Py2009: 219).

Even more importantly, a large deposit of animal bones was found in a thin layer of soil covering the river pebbles in the courtyard, probably corresponding with refuse disposal towards the end of the structure's occupation (Figure 8). According to preliminary faunal analysis, these bones represent pieces of dismembered cow and sheep carcasses. Rather than representing the remains of an entire carcass, they are instead from specific cuts of meat, probably associated with food preparation for a relatively large number of people.

Figure 8. View from the north of the cow and sheep bones found in the courtyard of the ‘tavern’ (photograph by Gaël Piquès).

Likewise, the ceramic evidence from zone 75 clearly shows several differences compared to assemblages found in domestic spaces at Lattara for the same period (zones 4-north, 5, 30 and 35), again suggesting that zone 75 was not merely one such space. Here, the ceramic data are exclusively from floor layers of these five different zones, probably representing the accumulated debris of broken ceramic vessels in use during the structure's occupation. Generally speaking, the kinds of vessels present in the domestic spaces from the contemporary residential areas of Lattara were also present in the occupation levels from zone 75: Beige Ware pitchers for pouring liquids; fineware black gloss bowls for drinking imported from Italy (almost all Campanian A); black gloss plates and larger black gloss bowls for eating (also Campanian A); large, locally made, non-wheel-thrown ceramic bowls for eating and serving; large non-wheel-thrown ceramics, called ‘jattes’, for cooking and serving; and non-wheel-thrown cooking pots. Two types of vessel are, however, over-represented in the assemblage: large non-wheel-thrown bowls and jattes, and black gloss drinking bowls.

For the first trend, compared with the domestic contexts for the same period, there are proportionally far fewer cooking pots from zone 75, and far more non-wheel-thrown bowls and jattes (Figure 9). In zones 4-north, 5, 30 and 35, cooking pots made up 60–80% of all non-wheel-thrown vessels, with jattes accounting for less than 13%. By contrast, in zone 75, cooking pots made up only 37% of the assemblage of non-wheel-thrown vessels, and jattes represented 24% of the assemblage. Cooking pots, as the name suggests, were often used for boiling food by being placed over a small hearth, but also for storage and drawing water. They would, therefore, probably have been less useful for cooking at zone 75, where the presence of three large bell-shaped ovens for cooking perhaps explains their under-representation. On the other hand, a larger number of bowls and jattes would have been necessary if crowds of people needed to be served food. Of the fragments of bowls and jattes from zone 75 from the occupation levels dating to 125–75 BC, most were quite large, with all but one measuring between 22 and 38cm in diameter (Figure 10). Conversely, in a domestic context, a significant number of these large bowls and jattes would have been unnecessary for small daily meals.

Figure 9. Percentage of bowls, jattes and cooking pots among all identifiable non-wheel-thrown sherds from the occupation layers of the respective zones.

Figure 10. Ceramics found from zone 75; on the left: non-wheel-thrown bowl (top) and jatte (bottom); on the right: Campanian A black gloss vessels; the bottom two were found as part of the votive deposit DP75162 (drawings by Benjamin Luley and Melissa Savanier).

With regard to the Campanian black gloss drinking bowls, there is a much greater proportion of this type of vessel present at zone 75 than for the contemporary zones 4-north, 5, 30 and 35 (Figure 11). Specifically, whereas in these other zones there is a relatively even proportion of Campanian drinking bowls, plates and eating bowls, in zone 75 there is a ratio of two drinking bowls for every plate and bowl. The implication of this over-representation is that drinking was a much more important activity in zone 75, something that certainly fits nicely with the presumed function of sector 3 as a dining hall, perhaps in the style of a Roman triclinium. Furthermore, black gloss plates and bowls may have been less important if food was served in larger, non-wheel-thrown jattes and bowls. One can easily imagine a scenario in which multiple diners ate from a large communal, non-wheel-thrown bowl, perhaps using the flatbread as individual plates, in a similar way to dining customs among many traditional societies today.

Figure 11. The percentage of pitchers, drinking bowls, plates and eating bowls (the last three categories are all in Campanian A) among all the identifiable sherds associated with dining and serving from the occupation layers of the respective zones.

Finally, a votive deposit (DP75162) found in the courtyard of zone 75 gives further insight into its possible function (Figure 12). Votive deposits, usually found buried in the floors of houses in non-wheel-thrown cooking pots, were common throughout Iron Age Mediterranean France, and often consisted of an offering of a cut of meat (generally pork or beef) or of some other animal (such as part or all of a bird or a snake) (Fabre Reference Fabre and Py1990). This deposit, however, was more unusual, consisting of a shallow, circular pit dug into the courtyard near the door to sector 3, within which was deposited a stone millstone base (meta), along with a Campanian drinking bowl (type CAMP-A 27c) and a Campanian plate (type CAMP-A 36), both turned upside down (Figure 10). A number of cuts of meat were placed under the millstone. The combination of a stone millstone, a bowl for drinking and a plate with cuts of meat could be interpreted as representing the principal activities associated with zone 75: grinding flour, producing large amounts of flatbread, consuming food (particularly meat) and drinking.

Figure 12. Votive deposit found in the courtyard of zone 75 (photograph by Gaël Piquès).

Conclusion

Based upon the evidence presented here, it appears that the courtyard complex of zone 75 functioned as a space for feeding large numbers of people, well beyond the needs of a single domestic unit or nuclear family. This is unusual, as large, ‘public’ communal spaces for preparing large amounts of food and eating together are essentially non-existent in Iron Age Mediterranean France. The presence of a number of large ovens and bases for grinding mills, the over-representation in the ceramic assemblages of drinking vessels and the presence of cuts of meat for large numbers of people, all match with the list of archaeological indicators of taverns given by Demarolle and Petit (Reference Demarolle, Petit and Bedon2011: 306–13). Furthermore, the appearance of this structure seems to correspond to a period in which there was a shift from a domestic-based subsistence economy to one increasingly based upon specialised artisan production. Although no coins were found within zone 75, the overall evidence from coins at the site certainly suggests the possibility that the food and drink distributed within the structure may have been exchanged through currency. In the context of a growing market-based economy, it is certainly possible that by the beginning of the first century BC there would have been an increasing demand among labourers and artisans for a place akin to a tavern to eat meals and socialise. The structure from zone 75 could have fulfilled this new need, and was ideally located at one of the town's entrances, with a large gateway of its own for allowing clients to access the courtyard from the street.

In this light, zone 75 arguably illustrates the relationship between taverns and a specific mode of production: in this case, one in which a relatively significant proportion of the population was no longer simply engaged in subsistence agriculture, but in artisanal production, and therefore increasingly reliant on alternative sources for daily meals. Due to the clearly precocious nature of the communal structure from zone 75, which dates to a period when these socio-economic changes were starting to occur, it is difficult to distinguish fully between a tavern and a site for communal eating. Certainly, the larger archaeological context of Lattara after the Roman conquest suggests that the economy was in the process of intensifying to the extent that labourers and artisans may have needed a new place for obtaining food, which they themselves were no longer always producing on a daily basis. At the same time, however, it is not impossible that food and drink may have also, under certain circumstances, been distributed along more traditional forms of economic exchange, such as commensality and gift giving, alongside more impersonal monetary exchange. Finally, although the communal structure at Lattara represents one of the few possible taverns for Roman Mediterranean France, and certainly the earliest, it is quite possible that its singularity is because few other sites have been as extensively excavated for so long. It is thus certainly possible that other indigenous sites may have also developed similar structures to the one at zone 75 in response to a changing and intensifying economy following the Roman conquest, a possibility that underscores an important avenue of research opening on the economy of the Roman world.