Introduction

When the antiquities trade is discussed in archaeology it is often prefixed with the pejorative adjective ‘illicit’. ‘Archaeology without context’ is a rallying cry for the archaeological profession to mobilise its collective voice in order to petition against the sale of heritage where an object's history is opaque and very probably a result of destructive looting (Chippindale et al. Reference Chippindale, Gill, Slater and Hamilton2001; Brodie Reference Brodie, Kersel, Luke and Tubb2006). The vocal campaign of the last decade to ensure that high-profile sales and museum acquisitions of material without documented collection histories do not encourage or sanction looting (e.g. Renfrew Reference Renfrew2000; Brodie et al. Reference Brodie, Kersel, Luke and Tubb2006) has had some success, although objects without findspots continue to surface on the market (e.g. Gill & Tsirogiannis Reference Gill and Tsirogiannis2011). That campaign, however, may have redistributed the weight of commercial value into another area that is far less clear-cut: the sale of archaeology itself. Documented context, accrued through professional archaeological practices, is now not only certifying specific auction lots, but is also potentially inflating their monetary value, sometimes substantially (Gill Reference Gill and Tsirogiannis2011: 52–53). These are often legal, but ethically problematic, transactions.

This article seeks to bring attention to this issue and to suggest possible responses from the profession in terms of ethics and stewardship. In addressing this problem however, we also have to confront the complex history and legacy of ‘partage’, a system that permitted the export of legally excavated material by foreign nations, but that frequently leaves more questions than answers concerning the ownership and possession of cultural heritage in the present. I would argue, therefore, that stewardship principles need to be established with a view to radical transparency, and with a flexibility that allows archaeologists to engage in critical dialogues on a case-by-case basis.

Archaeology with context

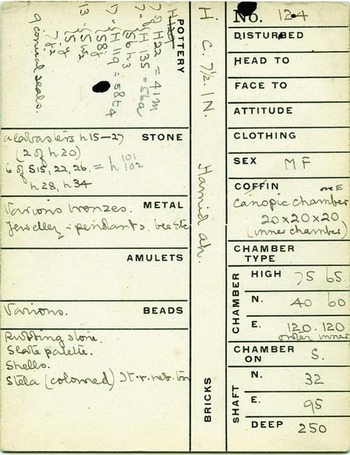

On 2 October 2014, Bonham's auction house, London, offered two lots of Egyptian antiquities for sale on behalf of the Archaeological Institute of America's (AIA) St Louis Chapter. The first (lot 160), billed as ‘the treasure of Harageh’ (Figure 1), comprised a group of travertine vessels and inlaid silver jewellery; the second (lot 162) was a travertine headrest (Bonhams 2014: 144–49, 151). Both derived from second-millennium BC assemblages excavated by teams working for Flinders Petrie'sBritish School of Archaeology in Egypt (BSAE) during 1913–1914. The former was removed from auction following the Metropolitan Museum of Art's intercession and a private sale for an undisclosed sum, while the latter exceeded its estimated price at auction and went into private hands. These objects have precise provenance documented through published accounts (Engelbach & Gunn Reference Engelbach and Gunn1923) and field notes (Figure 2). Such records allowed one academic—who also catalogued the material on behalf of Bonhams (2014: 148)—to build a compelling biography of these objects prior to their appearance on the market (Bianchi Reference Bianchi2013a & b), raising uncomfortable questions concerning the role of scholars in enhancing the commercial value of objects for the antiquities trade, consciously or unconsciously (Brodie Reference Brodie2011).

Figure 1. Inlaid jewellery from Harageh tomb 124 (UCL Petrie Museum of Egyptian Archaeology negative 1055).

Figure 2. Excavation record for Harageh 124 (UCL Petrie Museum of Egyptian Archaeology archives).

The BSAE's finds were originally exported in accordance with Egyptian laws that allowed those with an excavation licence to receive half of the discoveries, or the equivalent value, after the Cairo Museum's first selection (Khater Reference Khater1960). Once in London, the BSAE divided the finds between public institutions, as per their regulations (BSAE 1905: 8–9). The St Louis AIA, as one such sponsor, was allotted a share on the understanding that these were for a public institution. Their sale a century later contravenes that original agreement, albeit an agreement that seems not to have been documented in ways that stand up to legal scrutiny today. It was on ethical grounds, therefore, that a joint statement from UCL's Petrie Museum of Egyptian Archaeology and the Egypt Exploration Society (EES) was issued, condemning the actions of the St Louis AIA (Stevenson & Naunton Reference Stevenson and Naunton2014).

There was, nonetheless, a general academic and professional acquiescence surrounding the sale. Several commentators in social media noted that the auction was not illegal and, as Pitts (Reference Pitts2014) pointed out, that the St Louis lots were in fact one of the few that day that did not technically contravene UNESCO's 1970 international ‘Convention on the Means of Prohibiting and Preventing the Illicit Import, Export and Transfer of Ownership of Cultural Property’ treaty: more than 150 other lots did. For other observers, the sale was not even unethical, given that the AIA's code of ethics at that time (AIA 1997) only denounced “trade in undocumented antiquities” and “activities that enhance the commercial value of suchobjects”. There was no provision for a scenario in which well-documented archaeological material was marketed.

A month later, on 12 November, two Mesoamerican artefacts, again in the care of the St Louis AIA from documented excavations, were placed on Bonhams's New York auction block: a Zapotec seated urn from Monte Albán (lot 149) and a Maya Ek Chuah effigy vase (lot 156), excavated by Sylvanus Morley's teams, working under the aegis of the School of American Archaeology, at Quiriguá during 1910–1911 (Morley Reference Morley1935; Ashmore Reference Ashmore2007). The Maya vessel sold for almost three times its estimated value, despite the threat of legal action from the Mexican Government.

It is not the first time that the sale of archaeologically documented material has sparked controversy. In 2002, Charterhouse School in England sold its collection via Sotheby's (2002), including pre-Columbian South American pottery and Egyptian antiquities. Many had documented excavation histories, such as antiquities procured via the Egypt Exploration Fund. Protest was voiced in various media outlets (Kennedy Reference Kennedy2002), yet it was not debated in academia. Pressure from local archaeologists led to the removal of British prehistoric material, but the other items disappeared from the sales room into private ownership. Similarly, six years earlier, Christie's sold an Assyrian relief removed by A.H. Layard (Russell Reference Russell1997) on behalf of Canford School, Bournemouth. The Iraqi government protested, but their legal bid was thwarted as the monument was seemingly removed legally, as evidenced by an 1846 permit issued through the then Ottoman-Turkish government. The auction price reached at that time was the highest ever paid for an antiquity. Canford used the proceeds to expand its sports facilities.

The auction house problem

These sales raise acute problems on several fronts. For the archaeological objects themselves, being put on the auction block puts them at risk of disappearing into the private domain. Although it has been claimed that many collectors save and make material accessible in various ways, this is simply not a guaranteed outcome of commercial sale. Moreover, the integrity of the objects is no longer assured as there is currently no international legal protection, no ‘obligations of ownership’, for cultural property in private hands.

More broadly, the legal status of such archaeological sales confers an air of legitimacy to the antiquities trade, giving the impression that it is completely licit (Dietzler Reference Dietzler2013). This is amplified when museums purchase through sales, laudably rescuing artefacts from disappearing into unregulated private ownership on the one hand, but simultaneously leading auction houses to trumpet their status as legitimate, high-end brokers between clients and esteemed museums on the other. Yet however one looks at it, this is a ‘grey trade’, and the reality remains that illicit antiquities, lacking detailed ownership histories, are just as likely to be offered at the same sales (Watson Reference Watson1997; Bowman Reference Bowman2008; Brodie Reference Brodie2011: 409).

The steep premiums that these auctions achieve continue to be attractive sources of revenue. In recessions and times of austerity, this market appeal potentially destabilises the certitude that museums are long-term repositories, and fundamentally threatens public trust in them (Steel Reference Steel2015). For example, while none of the sellers cited above are accountable in the way that museums or similar institutions are supposed to be, the widely condemned sale in July 2014 of an ancient Egyptian statue by Northampton City Council at Christie's (sale 1541, The exceptional sale) shows that even things held in public trust are not necessarily safe from disposal via commercial auction (Heal Reference Heal2014). The statue was sold to an overseas private buyer for the exorbitant sum of £15 762 500, and the museum lost its accreditation from Arts Council England. Whereas academic pressure on curators was previously intended to ensure that museums did not acquire archaeology without context (Renfrew Reference Renfrew, Brodie, Kersel, Luke and Tubb2006), could museums be now increasingly looking to dispose of archaeology with context?

Inflated auction prices additionally garner considerable media attention and headlines, reducing archaeological finds to an economic value and undermining archaeologists’ attempts to promote more meaningful engagements with the past. Most seriously of all, these high prices and their media profile fuel powerful market forces that ultimately drive the pillaging of archaeological sites across the world (Gill Reference Gill2010: 6, Reference Gill2014; Hanna Reference Hanna2013). It is a lucrative trade for status- and profit-driven individuals, but it is not lucrative for source communities (Brodie Reference Brodie1998; Bowman Reference Bowman2008: 232). It is these groups who live in proximity to archaeological sites that stand to lose the most—not just in the short-term, but also in the long-term touristic potential of sites—especially in countries where there is political and economic instability such as Egypt, Syria, Libya and Iraq.

Complex histories

There are clear reasons then for critiquing the antiquities market, but countering instances where the products of legal archaeological work become financial assets is not always straightforward. This lack of clarity is largely due to the multiple routes by which objects have circulated from the field to the auction house, networks of exchange that are often poorly understood. If we are to have a dialogue and dissuade those that wish to sell archaeological heritage on the open market, it is necessary for archaeologists to be transparent about the history of their discipline and the legacy of collections procured during the nascent development of the subject.

In the UK, the absence of government-backed exploration meant that British fieldwork abroad was dependent upon both private patronage and public funding. This financial imperative placed an onus upon excavators to recover finds worthy of sponsorship, and archaeologists were under pressure to gain both scientific and popular assent, resulting in a wide diaspora of objects from field sites through partage agreements (Robson et al. Reference Robson, Horry, Taylor, Tinney and Zamazalová2014; Stevenson Reference Stevenson2014). Commercial considerations have long underpinned archaeological exploration (Sparks Reference Sparks2013).

Nevertheless, the regulations of organisations that administered these operations emphasised that excavated material was for public benefit, not private profit (BSAE 1905). No contracts were signed however, and documentation of any conditions of transfer has survived piecemeal, making it difficult to challenge many sales legally today. Although the original intentions of those who administered partage were that the material discovered should benefit the public, the sentiment was not absolute or equally applied. For instance, ‘duplicate’ objects were considered feasible tokens for private gifts or as incentives to garner further financial support (Stevenson Reference Stevenson2014). Even objects that remained in Cairo following partage were not always retained, and the Cairo Museum's Salle de Vente used to sell excavated objects until the mid-1970s (Piacentini Reference Piacentini and Piacentini2011: 26–28). The result is that archaeological finds have always been in private hands as well as public institutions, and these too have circulated through the antiquities market. Should we distinguish those archaeological artefacts from public collections to the sale room, from those disposed into private hands decades ago? The legacy of partage is far more problematic than is sometimes assumed (e.g. Cuno Reference Cuno2008).

Given this background, basing a challenge to sales such as that offered by the St Louis AIA upon a century-old agreement might seem anachronistic. I would argue, however, that this does not detract from our current ability to resist the transference of archaeological artefacts into commercial territory and then to private ownership wherever possible. We can adopt a position of “radical transparency”—a “mode of communication that admits accountability” (Marstine Reference Marstine and Marstine2011: 14)—in which we acknowledge both past failings and previous laissez-faire attitudes to the circulation of heritage; there are new opportunities to reinvigorate ethical debate to discourage the involvement of auction houses in the public sale of legally acquired archaeological finds. Such a position requires the archaeological profession to construct flexible frameworks for ethical debate that permit us to tackle sales on a case-by-case basis.

A question of stewardship

As the national AIA discovered in 2014, despite their condemnation of the decision made by the St Louis chapter of the AIA, the objects in their care were sold. It was only in the aftermath of this event that action to revoke the charter of the St Louis branch was discussed at the national AIA January 2015 annual meeting, but subsequently avoided when the St Louis AIA board resigned (AIA 2015a). The AIA are now addressing their ethical frameworks (AIA 2015b). Likewise, many current ethical guidelines of other professional bodies, museums and university departments, while taking a robust position against the market in undocumented finds, do not currently offer an effective means of addressing these sorts of sales, and may find themselves in a similar position to the AIA. Yet our stewardship responsibilities towards objects whose value was constructed by the discipline itself are surely of equal priority, as they are integral to our professional identity (Wylie Reference Wylie1996). Given the mixed legacy of archaeological finds distributions, it is, however, difficult to articulate proscriptive statements against legal sales of all archaeologically procured items. More recent conceptualisations of archaeological ethics, however, envision them not as stringent guidelines, but as a contingent form of negotiating politics and as a means of formulating an effective dialogue (Meskell & Pels Reference Meskell, Pels, Meskell and Pels2005; Scarre & Scarre Reference Scarre, Scarre, Scarre and Scarre2006: 3; Beaudry Reference Beaudry, Majewski and Gaimster2009), which may allow us to address the sales through radical transparency and open dialogue. When reassessing guidelines, the Society for American Archaeology's third principle is a particularly apropos departure point (Wylie Reference Wylie, Meskell and Pels2005: 54):

Whenever possible they [archaeologists] should discourage, and should themselves avoid, activities that enhance the commercial value of archaeological objects, especially objects that are not curated in public institutions, or readily available for scientific study, public interpretation, and display (SAA 1996).

I would appeal, therefore, to professional and archaeological societies to re-examine and debate their ethical stances with regard to both the sale of archaeological heritage more widely and the nature of the profession's relationships with auction houses. This might not mean denouncing all forms of interaction, given the debateable function of auction houses in facilitating the transfer of heritage from private hands to public museums, but these should be considered more carefully and critically on a case-by-case basis.

A second approach is to account for the whereabouts of the products of past excavations by making transparent the distribution of objects. A current AHRC-funded project, ‘Artefacts of Excavation’, is attempting to do just that for the finds from a century of British fieldwork in Egypt (Stevenson & Libonati Reference Stevenson and Libonati2015). This is not simply an information-gathering exercise. Rather, one of its aims is to give non-specialists enough information to make connections between objects and histories for themselves, thereby reanimating the narrative potential of ‘orphaned’ artefacts. This is important because in both the sales of the St Louis material and the Northampton statue, the fact that material was in storage was considered to be one, albeit short-sighted, justification for its disposal. There is no reason, especially in the digital age, for storage to be misconstrued as synonymous with inaccessibility. As stewards of the past, we do ourselves a disservice if we disregard the material legacies of past excavations and their latent potential for modern academic and public interpretation.

The concern over the legal sale of archaeological heritage might be seen as a histrionic reaction to what is currently a small-scale problem against the burgeoning trade in undocumented antiquities. Yet this is itself a reason to be more vocal in denouncing the few instances in which archaeological heritage is placed on the market: not only have we a strong case to make (e.g. Dillon Reference Dillon2015), we also have a moral obligation. These are objects excavated by colonial nations in foreign countries whose own resources are now frequently over-stretched tackling looting that is itself being undertaken for the first-world market. We should be responsible and accountable on their behalf for material we excavated and exported.

Conclusion

The antiquities market thrives on attaining the highest possible price for objects. It is simply not an appropriate conduit for transferring archaeological heritage, and auction houses should not be the middlemen for the disposal of material that was to remain in public trust. Private, discrete sales between museums or institutions are not being condemned here. Of concern is the public circus of commercialisation that is performed in the auction room, in which legally acquired antiquities are paraded as assets for the elite that can disappear into unregulated private territory. The price is not only high for the public profile of the archaeological profession and the trust held in museums but, more importantly, it is too high for source communities and archaeological sites around the world. Licit and illicit antiquities cannot be decoupled, as the commercial sale of the former still creates demand for the latter (cf. Brodie Reference Brodie2014). For these reasons, museums and archaeological institutions must take a stand.

Acknowledgements

I am grateful to Carla Antonaccio, William Carruthers, Thomas Morton, Simon Griffith, Emma Libonati, Christopher Naunton, Stephen Quirke and Alice Williams for helpful discussions on these issues, and to the two reviewers for their insights and suggestions.