Introduction

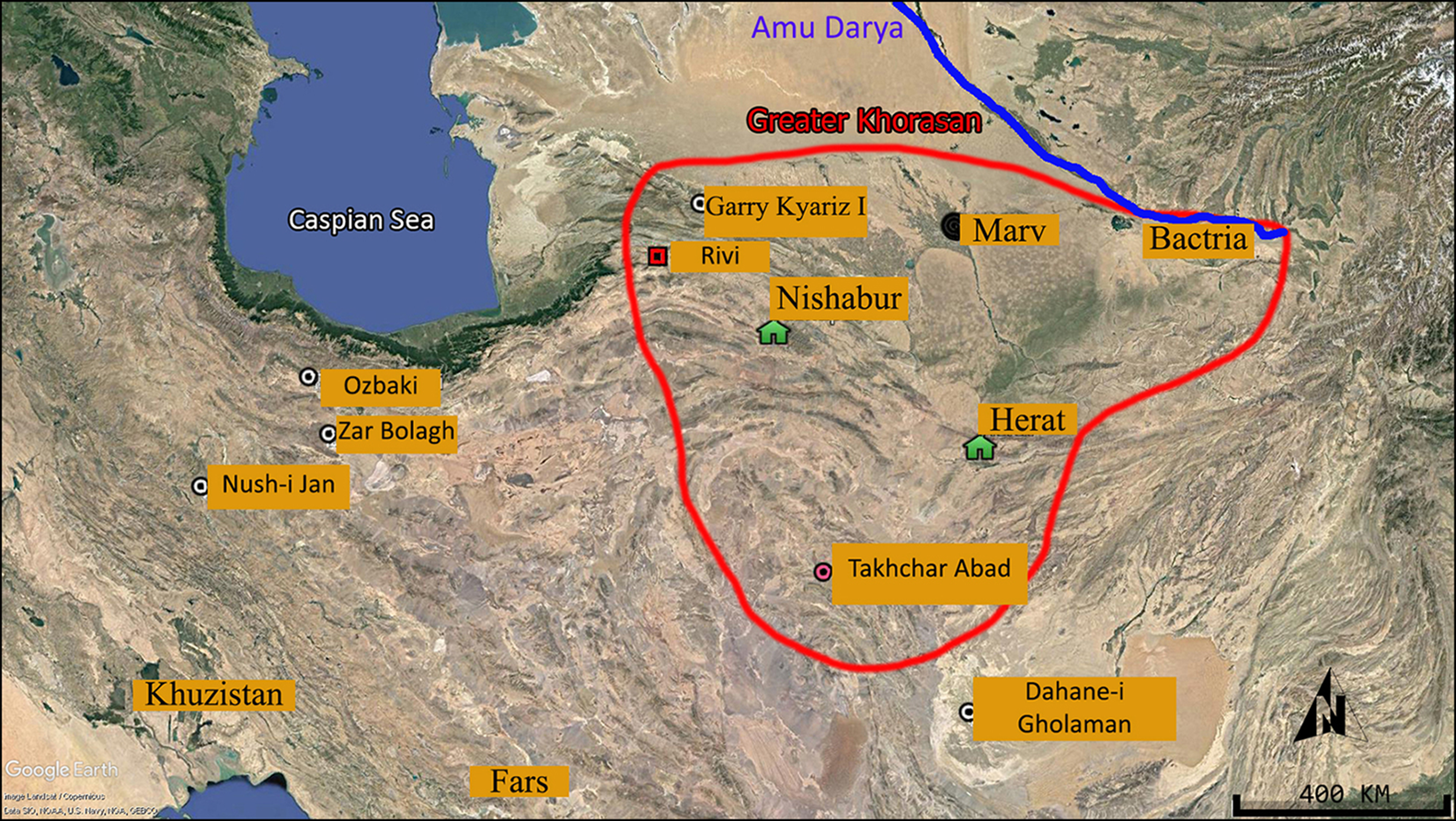

The Achaemenid period lasted about 200 years (550–330 BC). The territory of the Achaemenid Empire was the largest imperial region in the ancient world, encompassing land from the river Syr Darya (in central Asia) to Egypt. In terms of cultural materials, it is difficult to identify Achaemenid sites through surface material such as pottery because the cultural materials of the Achaemenid period are very similar to the period before it (Lecomte Reference Lecomte2005: 465; Lyonnet & Fontugne Reference Lyonnet and Fontugne2021). However, sites located in the Achaemenid Empire's centre, in Fars and Khuzestan (in south-west Iran), are easily recognised (Ataei Reference Ataei2007). In contrast, archaeological excavations have rarely been conducted in Iranian Khorasan (in north-east Iran). This is particularly unfortunate because the north-eastern parts of the Achaemenid Empire, south of the river Amu Darya, later became the historic region Greater Khorasan and played a vital role in the political and social history of western Asia.

Some scholars (e.g. Vogelsang Reference Vogelsang1992) have argued in favour of the coherence of archaeological evidence found in Greater Khorasan. In the east of Iran, only two archaeological sites had previously been excavated: Dahane-i Gholaman (Scerrato Reference Scerrato1996) in Sistan to the south of Khorasan and Tappe Rivi (Jafari et al. Reference Jafari and Thomalsky2016) in the north of Khorasan (Figure 1). In 2009, an almost circular adobe building with six towers was discovered and excavated in south Khorasan at Tappe Takhchar-Abad. It is located near Birjand and on the edge of a barren plain; no contemporaneous and related sites have been identified. Since then, there have been four excavation seasons. The distinctive plan of this building arguably belongs to the architectural tradition recognised more frequently on the eastern borders of Greater Khorasan.

Figure 1. Map of sites mentioned in this article (figure by authors).

Takhchar Abad building

Tappe Takhchar-Abad (Figure 2A) is near Takhchar Abad village (Figure 2B: 1) and 18km north-east of Birjand. This hill is semi-conical with a base diameter of 42m and height of 4m. Surrounding the hill is a ditch about 11m wide; its water was supplied by a waterway north-east of the ditch (Figures 2 & 3).

Figure 2. A) aerial view of location of Tappe Takhchar-Abad near Birjand. B) close-up of Tappe Takhchar-Abad: 1) the village; 2) the Tappe and ditch around it; 3) diversion dam (map from Google Earth; figure by authors).

Figure 3. Aerial photograph of the end of the fourth season's excavations at Tappe Takhchar-Abad, Towers 1–6 (figure by authors).

By the end of the four seasons of excavations, the remains of an almost circular adobe and pisé (Chineh/pakhsa) building with a diameter of 18m and six solid towers and a maximum of 3m-high walls were revealed. This building had been entirely covered with sand. Furthermore, two soundings indicated that this building was filled in two phases (Figure 3).

The first sounding revealed a 1m-thick peat layer deposited on the building's floor; the subsequent layer had been deliberately filled to a height of nearly 2m with alternating layers of broken or intact brick, sand and stones. The evidence suggests that after the building was filled, some structures were built on top during the Parthian period. The second sounding on the north side, external to the building, revealed a small, rectangular adobe structure at the foot of the external wall of the building, measuring 2m × 0.5m × 0.2m. There are also cracks at the top of the external wall that are similar in form to an arrow slit; however, because of the building's height, it is unlikely the building ever had a military use so they were probably not arrow slits but might have functioned as ventilation holes (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Top) small, rectangular adobe structure; below) building with slits (figure by authors).

Cultural materials and dating

The pottery discovered at Takhchar Abad can be divided into two separate phases: the late Iron Age/Achaemenid period (seventh–sixth centuries BC) and the Parthian period (third–fourth centuries AD). The pottery from the first phase is of the same type as seen in most regions of the Achaemenid Empire. This observation leads the authors to believe that the pottery represents an uninterrupted sequence from the late Iron Age to the Achaemenid period.

Before Takhchar Abad was established, some architectural constructions were deliberately filled in the west of Iran—for example, Nush-i Jan (Stronach & Roaf Reference Stronach and Roaf2007: 217), Ozbaki (Madjidzadeh Reference Madjidzadeh2010) and Zar Bolagh, which are generally dated to the Medes and Early Achaemenid periods (Malekzadeh et al. Reference Malekzadeh, Saeedyan and Naseri2014) (seventh–sixth centuries BC).

Traditionally, circular sites are attributed to the Parthian period (Ghirshman Reference Ghirshman1962: 34). Recent evidence suggests, however, that construction of these buildings began in Greater Khorasan during the Achaemenid period, initially in Bactria in the east of Greater Khorasan where about 10 such sites have been identified and excavated. Takhchar Abad is similar to Garry Kyariz I, located 67km north-west of Ashgabat in Turkmenistan. This building is circular with eight semi-oval towers (Figure 5), providing an occupation sequence from the Iron Age to the Achaemenid period (Pilipko Reference Pilipko1984).

Figure 5. Sketch plan of Garry Kyariz I (figure by Pilipko Reference Pilipko1984, fig. 1).

For the Takhchar Abad site, two types of absolute dating have been conducted. Some pottery samples from outside the building and under the rectangular adobe structure were subjected to thermoluminescence dating in the Research Institute of Cultural Heritage and Tourism in Tehran (Table 1). The results demonstrate that the building was constructed in the sixth century BC.

Table 1. Thermoluminescence dates on ceramic samples from Tappe Takhchar-Abad.

One bone sample from the floor of the building was also subjected to AMS radiocarbon dating at the Poznan laboratory (Table 2). The result indicates that the floor dates to the Seleucid period and that the abandonment of the main building of Takhchar-Abad took place in the third or second centuries BC.

Table 2. Radiocarbon date for Tappe Takhchar-Abad.

Conclusion

The evidence of pottery, building plan and absolute dating indicate that the Takhchar Abad building was constructed in the late Iron Age/Achaemenid period. This building was abandoned c. 500–400 BC, until the Parthian period (second and third centuries AD) when it was reoccupied; finally, it was filled and covered during the third–fourth centuries AD.

The construction of circular buildings and sites is an architectural tradition of the late Iron Age/Achaemenid period in Greater Khorasan, apparently originating from Bactria where the majority of such sites are found. Takhchar Abad in Greater Khorasan (east of Iran) and Garry Kyariz I in the north-west of Greater Khorasan (south of Turkmenistan) are the westernmost examples of this architectural tradition.