Introduction

Some decades ago, several authors (Baudrillard Reference Baudrillard1975; Berthoud & Sabelli Reference Berthoud and Sabelli1979; Lemmonier Reference Lemmonier1986; Miller Reference Miller1987; among others) recognised a problematic tendency within academia to define human populations according to their productivity. Scholars argued that the meaning, value and identity of social and material relations are limited to their productive-functional qualities. This resulted in a general universalisation of the production and economic field of societies as the determinant arena of social life. The ‘problem of production’ is also manifest in the study of archaeological materials (Miller Reference Miller1987: 3), more noticeably in frameworks inspired by cultural ecology (Binford Reference Binford1962) or political economy (D'Altroy & Earle Reference D'Altroy and Earle1985; Arnold Reference Arnold1996), which assume that the value of things is defined purely in the moment and context of their birth. This not only minimises the dynamics of subject-object relations, but also relegates social practices that do not quite fit these productive schemes (e.g. death, consumption and destruction) to the periphery. For these reasons, we prefer to centre our analysis within this periphery, focusing specifically on destruction.

Numerous alternative frameworks have confronted production-based essentialism (Appadurai Reference Appadurai and Appadurai1986; Kopytoff Reference Kopytoff and Appadurai1986; Miller Reference Miller1987). Many, inspired by the work of social theorists (Bourdieu Reference Bourdieu1977, Reference Bourdieu1984; Douglas & Isherwood Reference Douglas and Isherwood1979; Giddens Reference Giddens1984; Munn Reference Munn1986), recognise that the meanings ascribed to objects are historically constituted in practice, and that they change throughout the object's history. In a way, the ‘problem of production’ persists, however, as some aspects of the historical relations between subjects and objects remain hidden, especially those that concern the ‘death’ of objects (Colloredo-Mansfeld Reference Colloredo-Mansfeld2003). Consequently, destroyed objects are generally categorised as ‘rubbish’, and the importance of destructive acts has frequently gone unrecognised in the elaboration of semantic fields (as argued by Chapman 2000; Chapman & Gaydarska Reference Chapman and Gaydarska2007).

Several decades ago, Gerald Berthoud and Fabrizio Sabelli (Reference Berthoud and Sabelli1979) proposed the field of destruction as a possible analytical pathway towards the understanding of human societies, a concept also developed in a recent volume (Driessen Reference Driessen2013a). In the archaeology of the Ambato Valley (north-west Argentina) during the Period of Regional Integration (c. AD 600–1200), the particularly destructive abandonment history in this landscape of burning rooftops and collapsed structures seems difficult to understand from a functionalist-economist view. Here we examine some of the practices around the destruction of material culture within one of the most representative sites in this area, La Rinconada or Iglesia de los Indios (Figure 1), during its abandonment c. AD 1200. Our purpose is to identify destructive practices, and observe how broken things and practices of destruction might be charged with value. We hypothesise that the destruction and abandonment of this site, and possibly other sites in the region, unfolded as part of a ‘closing’ practice or ‘site funeral’, where the breakage of pottery played an important role.

Figure 1. Elevation model of the Ambato Valley (as indicated by the white ellipse) and adjacent regions, with the location of La Rinconada site (white point). Inset: political map of the Argentine Republic, with the location of the valley marked in grey within the Catamarca province.

Destruction as an approach

Our approach is informed by the work of Bourdieu (Reference Bourdieu1977), Miller (Reference Miller1987) and Chapman (2000). We consider destruction as a set of practices with their own purpose and signification that are objectified (in a dialectical process) in the historical relations between subjects and objects. This supposes that the meaning of destruction is part of a dynamic process that is constituted in time according to the agents’ dispositions, and integrated within a network along with other practices. Thus, any proposed definition is necessarily an arbitrary delimitation of the dynamic network of social practices. This implies that destruction is not inevitably constituted through a universal opposition with production, but that its relations with other practices will depend on the contexts in which it unfolds.

From this perspective, we understand destruction as part of the objectification process (sensu Miller Reference Miller1987; cf. Chapman 2000; Driessen Reference Driessen and Driessen2013b). In this way, we recognise its intentional quality, where ‘giving death’ to things constitutes another way in which a society constructs itself (e.g. Jaulin Reference Jaulin1967), and allows the archaeologist to interpret aspects of material culture that are practically imperceptible from a production-based approach. We do not seek a definition per se of destruction, but rather the exposure of its many dimensions (Driessen Reference Driessen and Driessen2013b: 5–8). In other words, we are attempting to understand the manner in which objects acquire value and how that value is manifested when they are destroyed (e.g. Chapman Reference Chapman, Gustafsson and Karlsson1999; Blanco-González Reference Blanco-González2015). We must contemplate that, in the transformation of objects to broken things, fragments can acquire an inalienable character (Chapman & Gaydarska Reference Chapman and Gaydarska2007: 9).

In this sense, Chapman (2000: 5) considers fragmentation as a social practice, dismissing the idea that fragments can only be conceived as ‘rubbish’, and instead assigning them a role in the construction of social relations and categories. He identifies a process that he entitles ‘enchainment’ within the European Balkan region during the Mesolithic, Neolithic and Chalcolithic periods. In this process, when subjects deliberately fragment an object and share its pieces with others, they generate a link not only between each other, but with the place where it is destroyed (Chapman 2000; Chapman & Gaydarska Reference Chapman and Gaydarska2007). Thus, the destruction of certain objects can be decisive in the social lives of agents.

In light of these considerations, we rethink some of the practices carried out by the inhabitants of the Ambato Valley through the analysis of broken pottery. We hypothesise that here the act of destruction was much more transcendental than merely accidental.

The archaeology of the Ambato Valley

Sites ascribed to the ‘Aguada of Ambato’ groups are distributed throughout the Ambato Valley (Pérez & Heredia Reference Pérez and Heredia1975). The region was inhabited between the seventh and twelfth centuries AD, known as the Middle Period or Period of Regional Integration, the character of which has long been debated. Indeed, while some authors (Pérez Gollán Reference Pérez Gollán1991; González Reference González1998; Laguens Reference Laguens2006) argue that the period aligns well with the emergence of complex societies, i.e. the introduction of hereditary socio-political hierarchies, others state that the archaeological evidence points towards the presence of a more heterogeneous socio-political structure without institutionalised hierarchies (Cruz 2006; Gordillo 2007).

Regardless of this ongoing debate, the archaeology of the Ambato Valley shows a considerable density and variety of settlements. It is not uncommon to encounter simple residential units coexisting with more prominent complex sites, which in turn are linked with farming areas that extend throughout the Los Puestos river basin (see Figueroa Reference Figueroa2013). All these sites present similar techniques and constructive styles (Cruz Reference Cruz2004; Gordillo Reference Gordillo2004), and share a common material culture and refuse (Cruz 2006: 137; Gordillo 2007: 86; Gastaldi Reference Gastaldi2010: 426). Among the objects shared by these populations are the distinctive engraved black ware (Cerámica Negra Grabada)—decorated in the Engraved Black Ambato style, an iconography centred on feline and anthropomorphous motifs—and large vessels with reddish surfaces overlaid by black and/or white painting (Tricoloured Ambato style).

Of particular interest here is the final departure of these populations, who abandoned the Ambato Valley around the start of the second millennium AD (see Gordillo Reference Gordillo and Vindrola-Padrós2013). Sites within the study area show notable similarities in terms of their final occupation contexts: their destruction by fire, and a chronological range that situates these abandonment events c. AD 950–1200. The manner in which this process occurred is still unknown. In the last decade, however, this topic has caught the attention of researchers including Gordillo (Reference Gordillo and Vindrola-Padrós2013), and Marconetto and Laguens (n.d.).

Diverse sets of ecological, economic, religious, political, social and demographic factors, both endogenous and exogenous, could have led the Ambato groups towards a situation of crisis and vulnerability. The catalyst of warfare can, however, be excluded due to the lack of evidence for inter-group conflict (direct or indirect) both in the material evidence and the bioarchaeological record; archaeological ‘warfare signatures’ such as weapons, defensive structures, outposts and towers, and iconographical elements of battle scenes are absent throughout the valley (Gordillo Reference Gordillo and Vindrola-Padrós2013: 376). Human remains, while presenting intentional manipulation and cut marks, do not fit into a warfare scenario, alluding instead to unrelated sacrificial practices (Gordillo & Solari Reference Gordillo and Solari2009).

Environmental conditions are argued to have played a central role in the process leading to abandonment. Increasing aridity in the region could have destabilised an already precarious agro-pastoral productive system (Dantas et al. Reference Dantas, Figueroa and Laguens2014: 161; Marconetto et al. Reference Marconetto, Gastaldi, Lindskoug and Laguens2014: 203–204; cf. Cruz 2006: 144). Yet if we consider, as suggested by Marconetto, an unfavourable environmental situation as the cause, we must also

analyse its role either as a potential trigger towards a situation of stress and social vulnerability, or as a catalyst for conflict [. . .] within the populations that inhabited the region. It is highlighted that the environmental causes do not exclude social dimensions, because groups respond to these situations in different ways, depending on cultural variables (Marconetto Reference Marconetto2009: 256, our translation).

In summary, this abandonment scenario may have been due to the unfavourable environmental conditions creating a situation of internal tension within the Ambato communities, rather than being related to conflict or warfare with external groups.

There are different interpretations relating to the manner in which the region was abandoned. Palaeoecological studies show that the carbonised remains found in most of these sites are the result of natural fires (Marconetto et al Reference Marconetto, Gastaldi, Lindskoug and Laguens2014: 204). Within the abandonment contexts described, however, the types of finds, their state and distribution are suggestive of the intentional destruction of objects and structures (Cruz 2006: 133; Gordillo Reference Gordillo and Vindrola-Padrós2013: 371, 380).

The site

La Rinconada is a ceremonial site located on the plains of the Ambato Valley floor; it was a densely occupied area during AD 600–1200. The site comprises a series of structures, built with two parallel filled walls made of rock and/or adobe, creating an orthogonal grid of adjoining units (Gordillo Reference Gordillo2004). This is arranged in a large U-shaped pattern with the open portion facing the west, enclosing an area of approximately 130 (north–south) × 120m (east–west) (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Plan of La Rinconada.

The layout of the various architectural units differentiates public and residential areas (Gordillo Reference Gordillo2004): the plaza or square, and its buildings including, to the south, a prominent, solid platform constructed with stone walls and filled with ‘rubbish’ and soil (E1 in Figure 2), and a series of dwellings located in the northern and eastern sectors of the site. These were composed of conjoining rooms with wooden, gabled roofs and lateral galleries set around large patios (courtyards). The patios constituted semi-public spaces for gatherings and interactions between private and public spheres. Within the rooms and patios, various domestic activities associated with the elaboration, consumption and storage of food and goods were carried out (Gordillo 2007), similar to those evident at other sites from the valley (Gastaldi Reference Gastaldi2010).

One of the most notable aspects of La Rinconada is the remnants of the fire(s) that are arguably associated with the last moment of occupation. In many sectors of the residential spaces, the burnt and collapsed roofs often lie over the occupation floors, thus sealing any materials that were in use at the time of abandonment and creating a direct stratigraphic relationship between the materials—including destroyed artefacts—and the carbonised roof remains (Gordillo Reference Gordillo2004). The low levels of weathering of faunal remains from the occupation floor, the presence of articulated llama bones and of bones with low density (e.g. hyoids), normally prone to rapid deterioration if not buried quickly, point to the same conclusions (Eguia Reference Eguia2012: 63–64).

The material culture appears, in different forms and measures, to have been affected by the collapse of the burnt roofs. Parts of the carbonised roof components (logs, branches and straw), as well as some weighted elements that supported the roof from above (torteros), appear over and among the materials. A significant density and variety of remains in the rooms and patios have been thermally altered.

If the final phase of the biographical cycle of this site included the general burning and collapse of the roofs over a large amount of material that was in use at the time, a strong link between the events of destruction and abandonment can then be established. La Rinconada provides a context of destruction that can be linked to the ultimate depopulation of the area, without any traces of Prehispanic reoccupation or reclamation (Gordillo Reference Gordillo and Vindrola-Padrós2013). As discussed in a previous paper (Gordillo Reference Gordillo and Vindrola-Padrós2013), we do not, however, subscribe to the view that the site corresponds to a “Pompeii-like context” (Blanco-González Reference Blanco-González2015: 353), but rather one that reflects an event with a high level of residuality and irreversibility (Lucas Reference Lucas2008: 62–63) due to the strong material imprint left in the landscape.

Within this framework, and in relation to the general interpretations regarding the firing and abandonment of La Rinconada, the present article focuses on determining the intentional destruction of objects that, in hypothetical terms, would have preceded this event as part of a closing practice, i.e. a ‘site funeral’. Our analysis centres on the ceramic sample recovered from the residential area of the north-east portion of the site, particularly the E5 patio (Figure 2).

Methodology

It was important to distinguish ceramics that were destroyed before the fire from those that suffered the impact of the burnt and collapsed roofs. To achieve this, the different factors that provoked the alteration of the materials found over the ancient occupation surfaces had to be discerned. Analysis involved the study of ceramic vessels from the E5 patio according to three variables: thermal alteration; fragmentation and dispersion; and the examination of contextual elements that might shed light on the manner in which they were destroyed.

Only sherds that did not exhibit any trace of fresh fractures were analysed, i.e. 1292 of the 1665 fragments recovered. Further, only vessels with a macroscopically established completeness above 30% were sampled. This allowed discrimination of vessels that were in use during the final moments of the site from older potsherds (Gordillo Reference Gordillo2004, Reference Gordillo, Nielsen, Rivolta, Seldes, Vázquez and Mercolli2007; Calomino Reference Calomino2012). The analytical unit employed was the de facto ceramic vessel (n = 42 for structure 5), but in relation to each vessel, we considered the fragment as the minimal unit (n = 1665 for structure 5) (see Table S1 in online supplementary material). Here, ‘de facto’ is used as an analytical category only to address those pots or parts of pots that, as indicated by their high level of completeness, are more likely to have been in use before the destructive events. In this sense, it slightly deviates from Schiffer's original definition (Reference Schiffer1972: 160).

We considered the following variables, where the refitting of the vessels was essential:

-

1) Thermal alteration: this analysis permitted the identification of signs of vessel fragmentation before the collapse of the roofs by the macroscopic analysis of soot formed on a potsherd, which contrasted highly with its contiguous refitted fragment. Part of this analysis centred on the differentiation of the thermal patterns created by the site's firing from those of previous activities, with reference to production- or use-related soot patterns (Hally Reference Hally1983; Skibo Reference Skibo1992).

-

2) Fragmentation: the objective here was to determine whether the assemblage was formed in one major episode (the collapse of the roofs) or several smaller events. For this analysis, the Fragmentation Index (FI; Schiffer 1983: 686) of all of the sampled vessels was calculated. The FI allowed the determination and comparison of the degree of fragmentation of each vessel through the quantification of their pieces. This index takes into account that fragmentation constitutes an exponential phenomenon (Byrd & Owens Reference Byrd and Owens1997: 316), which is why it is valuable in determining whether several episodes of breakage have produced an assemblage. We also monitored vessel attributes that might influence the FI values, such as the size of the vessels and the type of fabric.

-

3) Dispersion: this was analysed using the results from the refitting of the vessels, where the maximum distance of dispersion of the potsherds from a hypothetical centre was established—the centre of the square in which the majority of the vessels’ fragments were found, although in some cases, the presence of the base of the vessels was considered more indicative of their original position. The values obtained were approximate because the location for each sherd refers to a 1 × 1m square excavation unit. This analysis revealed patterns that might be associated with the transportation of fragments prior to the roofs’ collapse.

The contextual analysis sought features that might reflect the causes of breakage of the vessels, such as evidence for architectural collapse or signs of direct blows. Other aspects considered included the intentional deposition of artefacts, e.g. the presence of objects in non-habitual arrangements, the accumulation of items (including fragments as well as complete artefacts) in ‘odd deposits’, i.e. those generated with “accentuated ceremony” (Garrow Reference Garrow2012: 136), and the deposition of vessels in relation to circulation areas and access to other structures.

Results and discussion

The majority of the vessels were found to be at least 50% complete, and some more than 90%. Through the calculation of the volume of the vessels, three size categories were generated, reflecting their transportability (Menacho Reference Menacho2007: 155): small (highly transportable)—below 15L; medium (rarely transported)—above 15 but not more than 50L; and large (non-transportable)—more than 50L.

The FI values were generally below 0.5 (i.e. 80.95%), with the mode of the sample being 0.39, illustrating a moderately to highly fragmented ceramic assemblage (Figure 3). This is remarkable considering that the completeness of these vessels is generally above 50%. The value obtained for the correlation between the size of the inclusions in the ceramic fabrics (very coarse to very fine) and the number of fragments showed practically no incidence of the former in the fragmented state of the sampled vessels. Nevertheless, the size of the vessels does seem to be related to the number of sherds registered for each vessel and thus the FI values, i.e. the larger the vessel, the higher the number and size of fragments. Furthermore, through this analysis, some large and medium vessels were notable due to the small size of their composite sherds, e.g. vessels 114, 117, 119, 136, 137 and 138. The high level of completeness and high to moderate fragmentation support our hypothesis that the assemblage is the result of more than one event of destruction.

Figure 3. Fragmentation Index (top), and fragmented vessels in the central sector of the E5 patio (bottom).

The results of the dispersion analysis show low levels of movement for the fragments composing the ceramic vessels, yet the analysis highlighted at least three vessels (3, 4 and 138) that were a significant distance from the rest of the assemblage (Figure 4). Vessels 3 and 138 had maximum dispersion values of 6 and 4m respectively. Of note is vessel 4 (a complete vessel), a portion (40%) of which was found in the westernmost sector of the excavated area (squares 12f and 13f) and which was refitted with its missing portion (60%) located in another structure (E7; Figure 4). Hence, the vessel was divided into two portions that were separated by at least 10m with a wall between them. This implies the deliberate transportation of fragments of vessel 4, and perhaps also vessels 3 and 138.

Figure 4. Graph showing the dispersion of fragments per vessel.

From the 42 sampled vessels, the thermal-alteration analysis identified ceramic vessels with contrasting or discontinuous patterns for adjacent refitted sherds (Figure 5). A total of 16 vessels of different sizes and shapes were found to have different thermal alteration across conjoining fragments. Of these, four vessels had only one contrasting potsherd, or less than 10% of the vessel was represented by contrasting fragments. These were not included in the analysis (Figure 5).

Figure 5. Graph of thermal-alteration (top) and a detail of the contrast between fragments in vessel three (bottom).

Combining all three variables highlighted four of the vessels: 3, 4, 114 and 138 (see Table S1). It can be stated with a relative degree of certainty that these vessels were broken before the roofs’ collapse, with some of the fragments being transported to other areas of the site. It is, however, only by considering the context of the vessels that an argument for the existence of destruction practices can be articulated.

Contextual analysis

Several ceramic vessels (7, 115, 120, 121, 132 and 183; Figure 6) were found in association with the carbonised remains of the roofs and showed traces of impact; others (122, 177 and 178) were found associated with lithic objects that seem to have been used to destroy them—a situation also recorded in other structures of the site—supporting our hypothesis of intentional destruction (Figure 7). Vessel 122 was found close to the complete eastern wall of the patio, covered with rocks of different sizes. Sherds from vessels 177 and 178 were found beneath a large rock, while others from the same vessels were found nearby within vessel 180, a large container.

Figure 6. Burnt remains of the roof that collapsed over the vessels (E5).

Figure 7. Stones on a broken vessel (E5, north-west sector).

Two vessels, 126 and 127, show definite traces of being arranged in a deliberate manner. These were found in an inverse position (i.e. rim resting on the ground) and, within vessel 127, an entire child's skull was found just beneath a fragmented portion of the vessel (Figure 8; Gordillo & Solari Reference Gordillo and Solari2009).

Figure 8. Burnt logs and fragmented vessels. Number 126 lies inverted with an infant's skull inside.

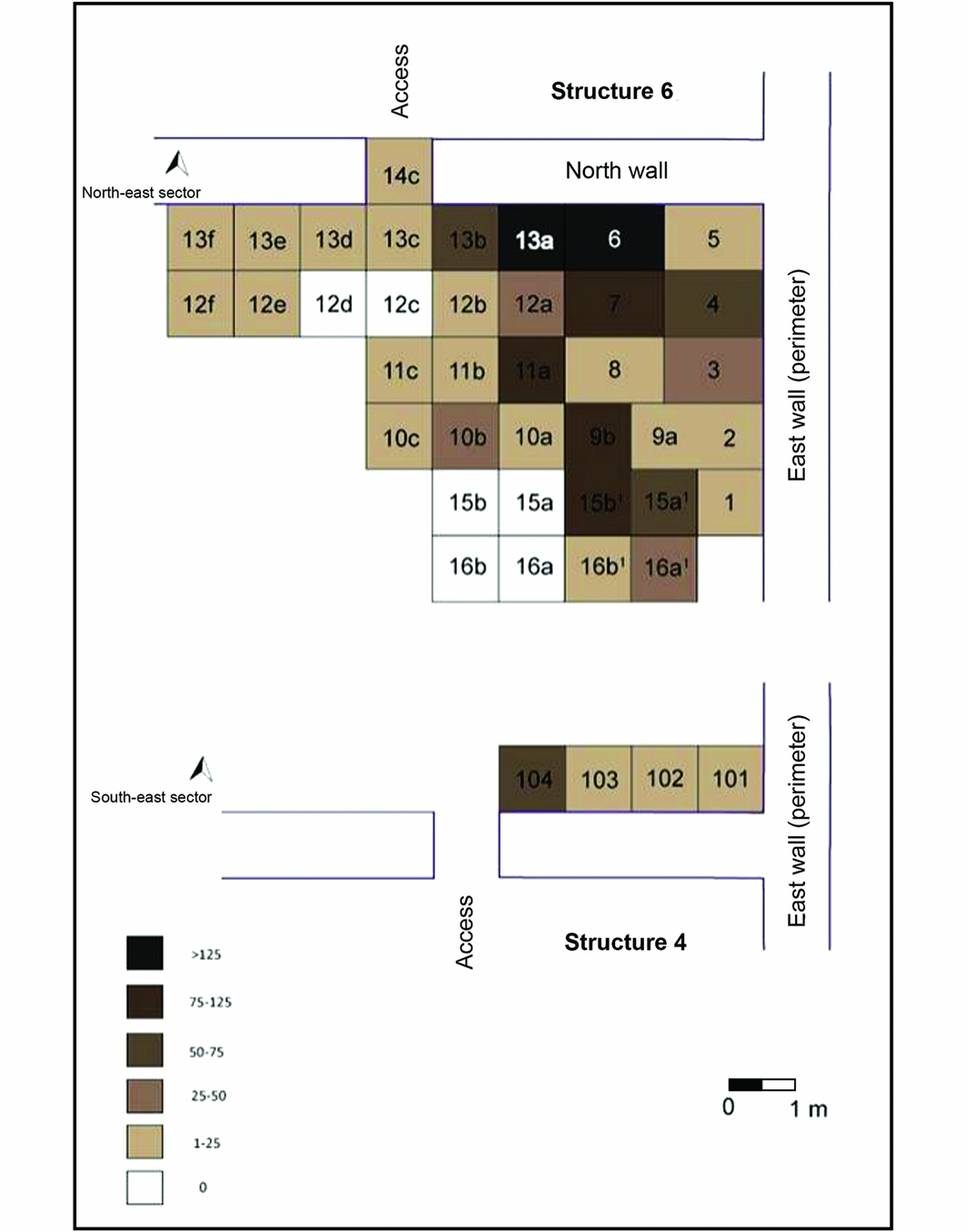

An area of concentrated fragments of material culture was highlighted by density and diversity maps (the latter as defined by Kintigh Reference Kintigh1984; Figure 9), as well as through the digitalisation and integration of the site's plans. During the excavation of the E5 patio, this concentrated area—confined approximately to squares 13a, 13b, 12a and 12b—was found to comprise a set of layers (1–4), all above the occupation surface: layer 1—the remains of the burnt roofs; layer 2—chañar seeds; layer 3—a layer of ceramic sherds at least 100mm thick; and layer 4—articulated Camelidae bones. It is possible that these strata were formed sequentially. Moreover, the general assemblage of this area is incredibly diverse, with items including human skull fragments, red pigment, carbonised corncobs, a cylindrical engraved lithic object, ceramic figurines and seven fragmented vessels. In sum, the high level of diversity and the high concentration of considerably complete yet extremely broken vessels (i.e. vessels 3, 13, 119, 138) lead us to designate this assemblage as an intended ceremonial deposition (Figure 10).

Figure 9. Density map of pottery fragments from vessels (E5).

Figure 10. Area with a concentration of fragmented materials (squares 13a, 13b, 12a, 12b).

Other evidence

It is important to add that the state of the human osteological remains of the E5 patio found on the occupation floor, in restricted areas associated with other de facto materials, and even within a vessel, resemble the ceramic assemblage described above. These human remains are almost exclusively skulls, which exhibit a high degree of fragmentation, varying degrees of thermal alteration (direct exposure to fire, but also boiling), intentional cut marks and signs of breakage with blunt objects (Gordillo & Solari Reference Gordillo and Solari2009; Solari et al. Reference Solari, Olivera, Gordillo, Bosch, Fetter, Lara and Novelo2013).

The E1 platform located in the public sector of the site is also worth mentioning in reference to the social life of fragments. This was the most prominent structure of the site, where ‘refuse’ was clearly delimited and contained by stone walls to create a space for communal ceremonial practices, thus preserving the testimony of previous generations in a confined and hierarchical space (Cruz Reference Cruz2004). This structure illustrates the general disposition of the La Rinconada inhabitants towards fragments and, quite possibly, fragmentation processes. Similar mounds are also observable at nearby sites from the same period, such as Piedras Blancas, and several sites on the eastern slopes of the Ambato Valley (Cruz Reference Cruz2004; Gastaldi Reference Gastaldi2010), where a significant number of potsherd refits suggest relationships between the different strata of the mounds.

Conclusion

In order to comprehend the general firing of La Rinconada fully, it is necessary to take the preceding destruction and deposition practices into account and vice versa, as these two processes are mutually constituted (Chapman Reference Chapman, Gustafsson and Karlsson1999). Our study of the material culture confirms the intentional destruction of the site based on evidence of the fragmentation of ceramics. The context, fragmentation and dispersion, as well as the manner in which the fire acted upon the ceramic material, show that at least 25% of the sampled vessels might have been used for these practices. In addition, the results raise new questions concerning the burning of the roofs, which could have occurred as part of a sequence of symbolic actions that preceded the site's abandonment (Gordillo Reference Gordillo and Vindrola-Padrós2013; Gordillo & Vindrola-Padrós Reference Gordillo and Vindrola-Padrós2013; Vindrola-Padrós Reference Vindrola-Padrós2015). This conflicts with claims that the destruction of sites in the region was generated by accidental or natural fires (Marconetto et al. Reference Marconetto, Gastaldi, Lindskoug and Laguens2014: 204; Marconetto & Laguens n.d.: 10).

The set of practices surrounding the destruction of material culture would have unfolded in a selective manner, privileging only some objects for this purpose, in private and semi-public spaces, before the roofs collapsed. These practices were associated with the site's final abandonment because, in common with other sites around the region, there is no evidence that suggests the recurrence of this destructive event or the reoccupation of the site (Gordillo Reference Gordillo and Vindrola-Padrós2013). In this sense, the deliberate destruction of objects and the burning of the site do not appear to be cyclical (cf. Gordillo & Leiton Reference Gordillo, Leiton, Korstanje, Lazzari, Basile, Bugliani, Lema, Pereyra Domingorena and Quesada2015).

Fragments, often wrongfully labelled as ‘rubbish’, allude to the history of this place. Broken ceramics constitute a physical and symbolic medium of public ritual, as also seen in the evidence obtained from the platform-mound (E1). In this sense, “the domesticated past transcends in the public domain, within which collective memory is constructed—partially materialized in rubbish—through an old material discourse that lays out a new regimen of social and spatial interpretation” (Gordillo 2007: 86).

Broken things can evoke memories and enable projection. They refer to the past by alluding to ancestors, and in relation to the future, they can release the burden of permanence and open new pathways. In this particular abandonment scenario, destruction was probably the action that allowed departure and motivated people to start again in a new location. We believe, as Brück does, that “deliberate breakage was not simply a symbolic act but was thought to facilitate transformation from one state to another” (Brück Reference Brück2006: 297). This is how destruction, understood as objectification, grants us a different perspective on material culture: societies can be understood not only through the manner in which they produce, but also through the ways in which they (creatively) destroy.

Acknowledgements

We thank the members of our research team for their valuable contribution over the years, especially Liliana Milani for assisting with the translation of this article. We would also like to thank the reviewers and editors for their constructive comments. Lastly, we wish to thank Diego Gobbo for providing us with the 3D elevation model of north-west Argentina. The research conducted was supported by the SECyT (UBACYT 20020100100340 y 20020130100108BA).

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit http://doi.org/10.15184/aqy.2016.259