Despite archaeological interest in the study of the origins of public architecture in the Andes, there remain a number of gaps in our knowledge, especially in the area between the Chancay and Lurin Valleys on the central coast of Peru. This situation may, in part, result from how we have approached the study of the Formative period. In particular, the lack of intensive studies in several types of sites and valleys means that we have incomplete knowledge of wider settlement systems. As a result, we know very little about the existence of smaller settlements, only the great public centres. Nor do we understand how the unique occupational histories of each site and valley developed. This is despite the fact that investigations of the period began with middens and sites with modest architecture such as Bellavista or Ancón (Uhle Reference Uhle1906; Rosas Reference Rosas2007). Yet this shortcoming has not been an obstacle to formulating explanatory models, which have focused on the origin of early public architecture. The current dominant explanatory model for the emergence of architectural monumentality focuses on the concept of the concentration of power (e.g. Haas Reference Haas1982; Trigger Reference Trigger1990). Our project at El Pacífico takes a different perspective, seeing these mounds as a palimpsest of social experiences and socially constructed places to preserve community memory and traditional patterns of life (Dillehay Reference Dillehay1990; Tilley Reference Tilley1994; Rosenswig & Burger Reference Rosenswig and Burger2012; Flores Reference Flores2014).

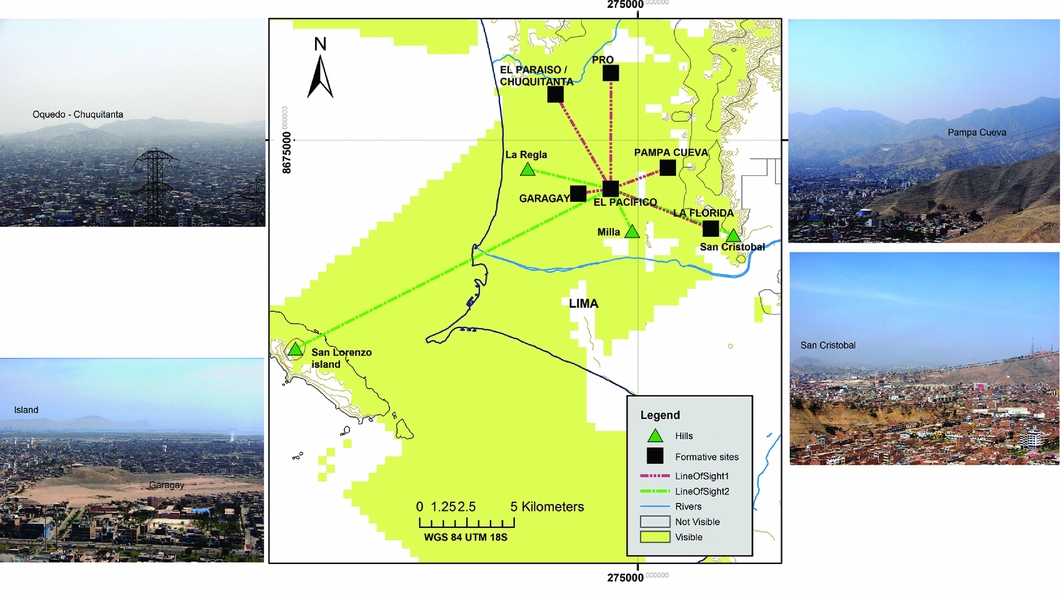

El Pacífico is located between the basins of the Rivers Chillón, to the north, and Rímac, to the south, on the central coast of the Central Andes (Figure 1). It consists of two small mounds with a complex stratigraphy of several overlapping occupations, demonstrating a longer history of activity than originally proposed by the discoverers of the site (Traslaviña et al. Reference Traslaviña, Haro and Bautista2007). El Pacífico was first occupied during the final phase of the Late Archaic or Initial Formative period (2200–1800 BC), which is contemporaneous with settlements such as Caral or El Paraíso (pristine complex social developments). Occupation continued until the Early Formative period (1800–1000 BC), prior to the expansion of the Chavín culture's influence into the north-central coast of Peru (Quilter Reference Quilter1985; Shady & Leyva Reference Shady and Leyva2003; Rick et al. Reference Rick, Mesia, Contreras, Kembel, Rick, Sayre and Wolf2009). The Pacífico settlement is atypical in that it lacks the scale and macro-spatial order (e.g. pyramidal buildings arranged in a U-shaped pattern) of the great power centres of the Formative period of the central coast of the Andes (e.g. the nearby site of Garagay), and also because it is located on a hill. The initiation of research on this settlement in 2016 is therefore important to Andean archaeology as it promises new insights into how Andean societies produced monumental places and generated communal ties.

Figure 1. General map of part of the central coast of Peru and the location of the site of El Pacífico (map by Luis A. Flores).

The archaeological features of El Pacífico are grouped into two sectors located at two different altitudes (Figure 2):

-

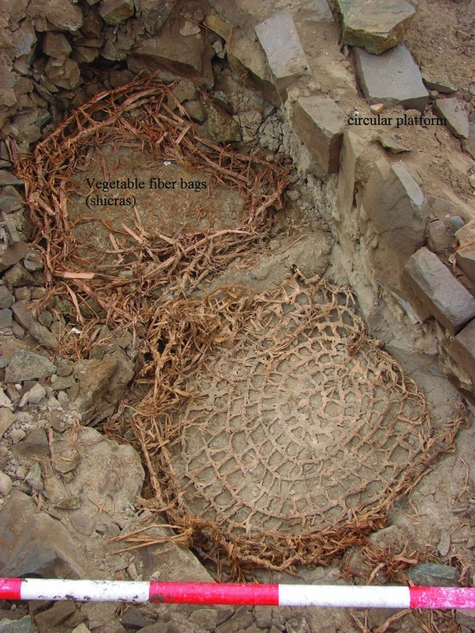

• Sector A, the lower mound (at 100m asl), is located in the south-eastern part of the site and shows a stratigraphic profile, approximately 60m long, exposed due to the destruction of part of the mound (Figure 3). This reveals a succession of overlapping platform walls, a classic example of the burial of earlier structures (Bonnier Reference Bonnier1997). A 2 × 2m pit at the top of the structure revealed a 2m overlap of construction fill, consisting of a stratum of vegetable-fibre bags (shicras) covering structures of angular stones. Among these layers were a few fragments of Early Formative ceramics. Underneath the fill it was possible to identify a pre-ceramic level of at least 4m in thickness.

-

• • Sector B is a mound on the highest part of a rocky hill, at 150m asl (Figure 4). It is a quadrangular mound 40 × 40m, and 10m in height. The hill was covered with terraces of stone, giving a stepped appearance. At the top of this mound, we excavated seven units (an area of 29m2), revealing up to three overlapping periods of construction. From top to bottom, these consist of a large building, facing north-west, featuring at least two large quadrangular enclosures with multi clay floors. Beneath this was a layer of stones bagged in fibres (shicras) that covered a low circular platform (Figure 5). Under this occupation, in another unit, we discovered a pre-ceramic layer, containing cotton and guava seeds, itself covering a straight stone wall.

Figure 2. Orthophotograph of El Pacífico hill where two archaeological sectors have been recognised (photograph produced by Arquesystems).

Figure 3. Aerial photograph of sector A showing the excavated unit (photograph by Remote Sensing-Comtec).

Figure 4. Oblique aerial photograph of sector B showing the excavated units (figure by Luis A. Flores, based on a photograph by Remote Sensing-Comtec).

Figure 5. Photograph of the deposit of fibre bags covering the circular platform (sector B) (photograph by Luis A. Flores).

In addition to excavations at the site, we are also researching its location within the wider region. Viewshed analysis demonstrates that El Pacífico has almost complete visibility over the inter-basin area and, at the same time, was itself visible from other contemporaneous settlements and various natural points. The settlement was a landmark in a larger visual field that formed a powerful social landscape (Figure 6).

Figure 6. Map and photographs of the viewshed from El Pacífico to other contemporaneous sites and natural places in the landscape (map and photographs by Luis A. Flores).

At the macro-spatial level, the geographic location of the site in a central position between two valleys, from where it was highly visible, induces us to think that the construction of the site may have represented the first attempt to organise the ancient landscape of pre-Hispanic Lima, where El Pacífico represented a central node in a larger system of settlements. At the micro-spatial level, it has been possible to determine that the site's builders made modifications to the hill itself, cutting into the natural rock, encasing it with stone-walled platforms and depositing clean construction fills as part of a structure burial process, widely documented in the Andes (Bonnier Reference Bonnier1997); over time, this generated the two mounds at El Pacífico. The evidence suggests a communal use of space that perhaps served as a major source of social cohesion among multiple-households. Clearly, the social group based in the area appropriated this natural location, making it an anthropologically meaningful place. Even after its abandonment, the site continued to have meaning for subsequent societies, as evidenced by an intrusive burial of two sacrificed llamas (Lama glama) dated to at least 2000 years ago.

Acknowledgements

This project was made possible by a network of colleagues and other professionals. Special thanks to N. Gamarra, L. Cayo, K. Herrera, K. Flores, L. Loza, A. Infantes, A. Altamirano, C. Alarcón, R. Paucar, E. Chavez, L. Miranda, H. Walde, J. Pérez, G. Tuesta, L. Zelada, N. Roa, J. Chacón, D. Maravi, P. Salvador, C. Moreno, R. Huamán and M. Castillo, among others. Similar thanks go to the students of the Universities San Marcos and Federico Villarreal in Peru, who helped during the investigation. Acknowledgement is also due to the Municipality of Los Olivos (especially to S. Tácunan), the Ministry of Culture of Peru for giving us permission (R.D. N° 214) and to Arqueosystems SAC and Remote Sensing-Comtec for aerial photography. Finally, thanks to E. Arkush and R. Haas for reviewing the text.