The volcanic landscape of southern Etruria (northern Lazio, Italy), once the heartland of the Etruscan city-states, has existed in the shadows of Rome since the Roman conquest of the region in the fourth century BC. The archaeology of this often neglected region offers insights into globally relevant questions about the interrelationships between settlement patterns and political centralisation. Over 50 years ago, Ward-Perkins (Reference Ward-Perkins1962) identified a cyclical settlement pattern in the region. Based on his South Etruria Survey, Ward-Perkins suggested that alternating periods of political fragmentation and centralisation resulted in two basic settlement patterns: one prioritising defence, and a second privileging economic integration with a wider polity.

The Etruscans of this region lived primarily in competing city-states, building fortified settlements atop defensible plateaus. After the Roman conquest, settlements moved down to the lowlands, where extensive villa agriculture was practised near Roman roads. The pattern was reversed sometime between AD 700 and 1100, with habitation shifting back to plateau tops, where small castles paired with villages often reoccupied the edges of former Etruscan cities. This nearly ubiquitous medieval transition to fortified villages, known as incastellamento, extends across the North-western Mediterranean and has been the subject of much debate. Historians date the transformation in Italy to the tenth to eleventh centuries (Toubert Reference Toubert1973), while archaeologists posit a gradual transition beginning in the eighth century (Francovich & Hodges Reference Francovich and Hodges2003). Only with the emergence of the modern Italian state did settlements once again move down from Lazio's fortified plateaus (Ward-Perkins Reference Ward-Perkins1962). We initiated the San Giuliano Archaeological Research Project (SGARP) to provide new archaeological information about these important settlement shifts. We have completed two field seasons (2016 and 2017) at San Giuliano, a site known for its many rock-cut Etruscan tombs (Figure 1). Despite its repute, the location of the Etruscan urban settlement is currently unknown, and the Roman and medieval periods have not been the subject of systematic investigation.

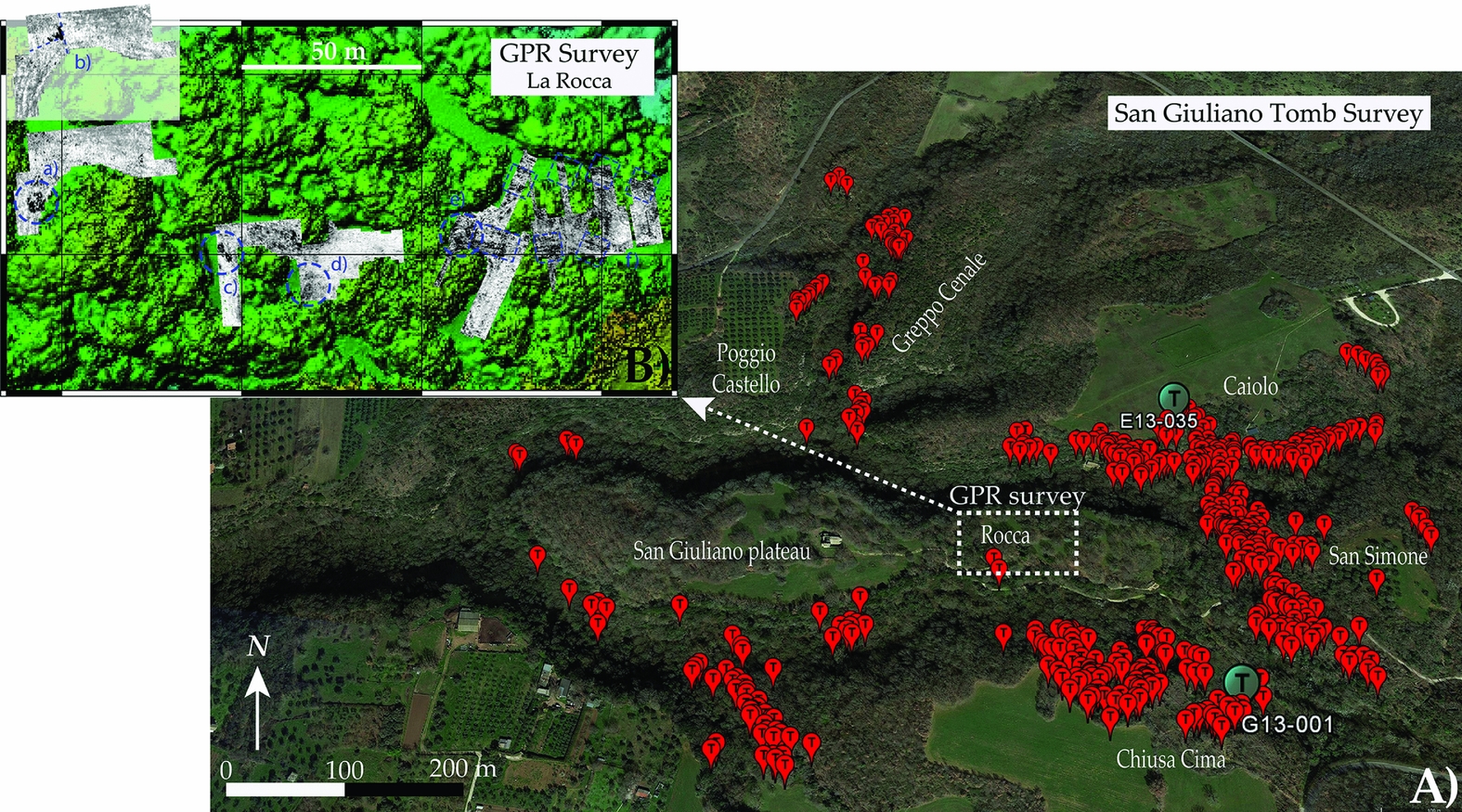

Figure 1. Northern Lazio (© SGARP, San Giuliano Archaeological Research Project).

Etruscan necropolis and town

Previous work at San Giuliano has focused on the Etruscan necropolis, particularly tomb typologies (Gargana Reference Gargana1931). Our goal is to examine the interrelationship between the tombs and the habitation zone to illuminate the socio-economic organisation of Etruscan San Giuliano. To achieve this aim, we have focused on documenting the tombs, carrying out salvage excavations of looted tombs and locating the urban centre. We have documented over 500 previously unmapped tombs, which cluster into geographic concentrations that probably reflect kinship groups (Figure 2). The next stage of our work focuses on inter-tomb and tomb-to-settlement landscape analyses, paired with further excavation of selected tombs from each tomb cluster.

Figure 2. A) San Giuliano, surveyed tombs in red, excavated tombs in light blue; B) ground-penetrating radar survey, green lines indicate potential structures, features and a tunnel (upper left) (© SGARP; credit for insert B: Working Group in Applied Geophysics at Kiel University).

Excavations of two looted tombs show significant promise for artefact and human bone recovery (Figures 3 & 4). We collected over 4000 ceramic sherds of bucchero, black-figure and red impasto wares that date the tombs to the sixth century BC. Tomb G13-001 yielded 1535 human bone fragments from at least 12 adults, consistent with long-term use as a collective tomb. Future work will include aDNA and isotope analysis to determine the familial relationships and geographic origins of the interred individuals. Except for circuit walls, a few cuniculi (drainage tunnels) and a cistern, San Giuliano's Etruscan urban centre remains undiscovered. Our ground-penetrating radar surveys, however, revealed subterranean features that may represent Etruscan structures (Figure 2). Future excavation will target these features, near which systematic surface survey has recovered Etruscan pottery.

Figure 3. Tomb E13-035: A) sediment-filled interior before excavation; B) ceramic scatter on floor during excavation; C) external dromos; D) after excavation (© SGARP).

Figure 4. Pithos (storage jar) fragment from tomb G13-001 (© SGARP).

Medieval castle and fortified village

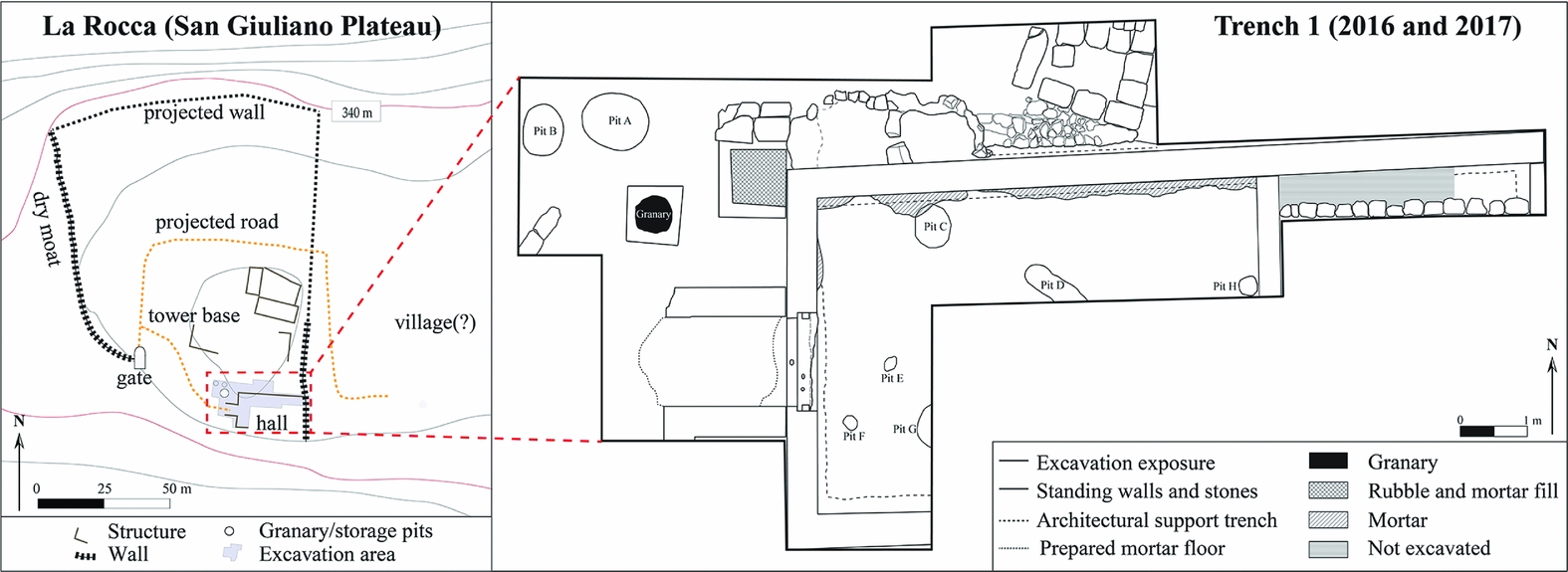

SGARP's strategic excavations of medieval ruins atop the San Giuliano plateau are illuminating the medieval reoccupation of Etruscan defensive sites. Focusing on the plateau's eastern end—known as La Rocca—our surveys and mapping revealed a fortified zone of substantial organisational complexity. The small castle complex includes a tower, dry moat, circuit walls and a road with at least two gates leading to the village (Figure 5).

Figure 5. La Rocca (© SGARP).

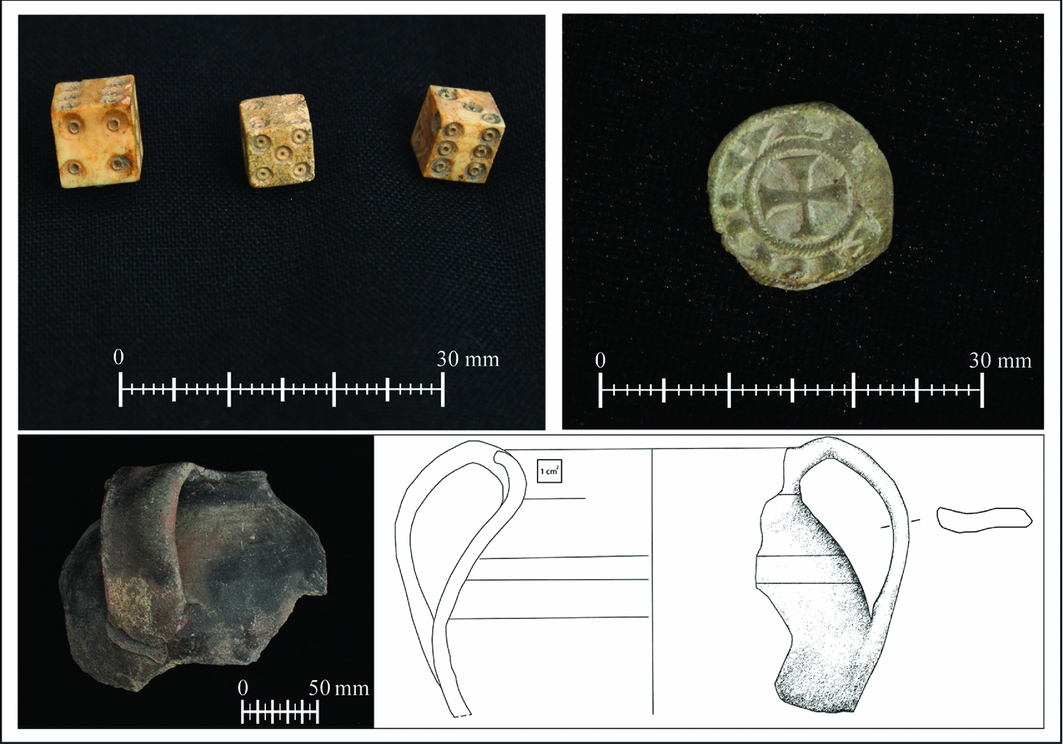

Our excavations have so far revealed a courtyard with a granary and two storage pits, all reused for refuse disposal. A roofed passageway controlled access from the courtyard into a large rectangular room that we interpret as a communal hall. Artefacts therein, including fine glassware and ceramic servingware, alongside archaeozoological analysis of refuse deposited in the granary, suggest that people dined here. Sheep and goat were the most prevalent food animals, although the faunal bones (N = 4003) also include feast animals, such as pig. Stylistic analyses of ceramics, glassware and coins indicate that the hall was used in the eleventh to twelfth centuries (Figure 6).

Figure 6. Finds from La Rocca (© SGARP).

Continued excavations of the castle and village zone will yield data to test three explanatory models for the incastellamento process: 1) manifestation of state power; 2) privatised feudal enterprise; and 3) communal village-based initiative. Particularly important are the timing and character of the medieval reoccupation. This region lay on the Byzantine-Lombard border in the eighth to ninth centuries, and earlier community excavations identified graves tentatively dated to this period (Guerrini Reference Guerrini and De Minicis2003). A Byzantine or Lombard stronghold would coincide with our first model: a defensive complex built by a state-level polity. In contrast, the dates from the hall coincide with the feudal period and favour the privatised enterprise model. Further excavations are necessary to determine whether the castle was an elite residence or a communally organised fortification. Considering the scarcity of written seventh- to eleventh-century sources from northern Lazio, archaeology affords the only viable means to investigate these models.

Acknowledgements

We thank our partners of the Virgil Academy (Rome), at Parco Marturanum, at the Italian Soprintendenza and in the town of Barbarano Romano.