Introduction

Despite the Vikings’ reputation for raiding and trading, the Viking Age in Denmark (c. AD 800–1050) was a time of state formation. A key figure in this process was King Harald Bluetooth (died c. 987), son of King Gorm and Queen Thyra. There are few written sources documenting these political and societal events and little is known about Gorm and Thyra. They are, however, named on two runestones at the royal site of Jelling: one, smaller, stone was erected in Thyra's honour by Gorm, the other, larger stone, raised by Harald to commemorate both parents (Table 1).

Table 1. The seven investigated runestones in southern Jutland and their inscriptions. Bold characters represent runes transliterated to Roman letters.

Our knowledge of Gorm's accession in, probably, c. AD 936 and reign is limited. The eleventh-century historian Adam of Bremen states that Gorm came from either Norway or Normandy, which has led to the suggestion of Gorm being a Stranger King who seized power in Denmark (Dobat Reference Dobat2015). The late twelfth-century historians Sven Aggesen and Saxo Grammaticus describe Gorm as a weak and lazy person, whereas the Norwegian sagas emphasise his talents as a warrior (Lund Reference Lund2020: 136). Exactly how Gorm's reign ended is also unclear, though he appears to have been replaced by his son, Harald, during the visit to Denmark in the 960s of the cleric Poppo, who baptised the new king (Lund Reference Lund2020: 131‒7).

Gorm's wife Thyra is one of the very few women mentioned in legend and written sources. Aggesen and Saxo introduce her as the sage and sturdy queen who commissioned the building of the Danevirke, a linear earthwork to defend Denmark against southern intruders. Saxo refers to her as the daughter of the English king, but the sagas place her in Jutland as the daughter of semi-legendary Clac-Harald (Lund Reference Lund2020: 142). The smaller runestone in Jelling refers to Thyra as Danmarkaʀ bót, meaning ‘Denmark's adornment’ (Nielsen Reference Nielsen1943, Reference Nielsen1946) or ‘Denmark's strength/salvation’ (Jacobsen Reference Jacobsen1945; Olsen Reference Olsen2012).

Compared with historical texts, the archaeological sources of Viking-Age Denmark are more plentiful but not necessarily more explicit. The centre of Harald's dynasty was the site of Jelling, a complex of more than 12.5ha, enclosed by a wooden palisade of trapezoidal plan. Inside the enclosure are two extant large mounds, the northernmost of these is encircled by a 360m-long ship-setting; positioned between the mounds, are a church and the two runestones (Holst et al. Reference Holst2013; Dengsø Jessen et al. Reference Dengsø Jessen2014). The larger Jelling stone is believed to stand in its original position, whereas the smaller stone is believed to have been placed as the stern stone of the large ship-setting, encircling the northern mound before being relocated to its present position near the church (Imer Reference Imer2016: 163; Lund Reference Lund2020: 139). By tradition, the northern mound is known as Thyra's mound, and the southern as Gorm's. In 1820–21, excavations of the northern mound revealed the remnants of a grave chamber though with no evidence of a body; wooden artefacts from the chamber were later dated by dendro-chronology to AD 959/60 (Krogh Reference Krogh1993: 217). In 1976–79, excavations beneath the floor of Jelling church revealed a grave containing a male skeleton. Researchers concluded that it was Gorm, who was initially buried in the chamber of the northern mound and later moved to the church by his Christian son (Krogh Reference Krogh1993: 233‒8); this assumption was made despite the fact that the northern mound was traditionally ascribed to the queen and no direct link between the two contexts—the empty grave in the northern mound and the grave in the church—could be established (Lund Reference Lund and Kryger2014: 62‒4, Reference Lund2020: 147).

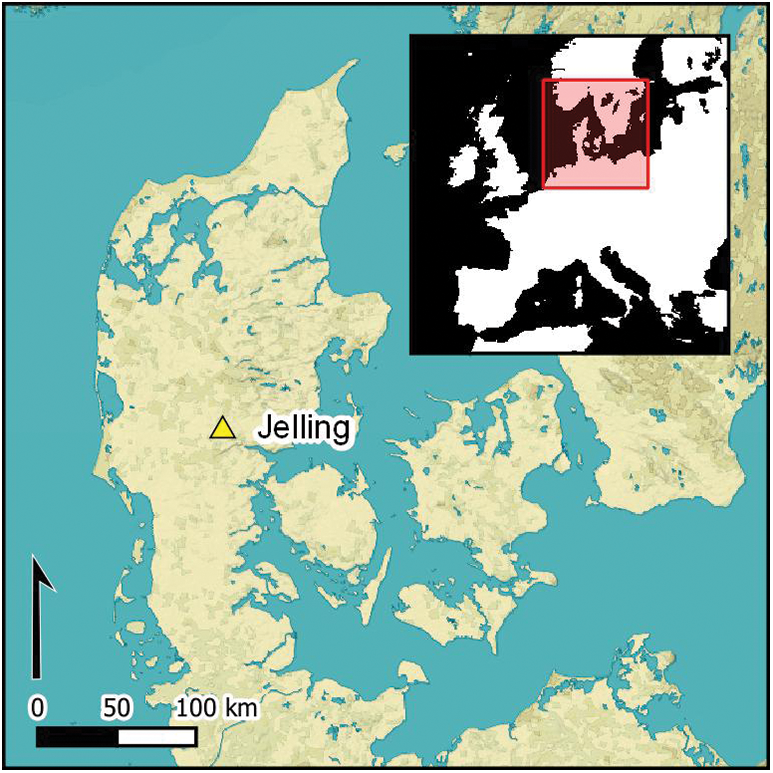

Turning to Thyra, although she is recorded as a queen, details of where and how she reigned are unclear. These questions have been discussed on the basis of seven runestones from southern and western Denmark that are dated to the mid-tenth century AD (e.g. Stoklund Reference Stoklund and Iversen1991: 297; Imer Reference Imer2015: 5–7). Two of these are in Jelling, erected by Gorm and Harald in her honour. Four are connected to an individual who identifies themself as Ravnunge-Tue—Bække 1 and 2 (Jacobsen & Moltke Reference Jacobsen and Moltke1942: DR 29 & 30), Læborg (DR 26) and Horne (DR 34). They are collectively known as the Bække-Læborg group (Figure 1). A fifth is the Randbøl stone (DR 40; Table 1). The Randbøl stone mentions Tue Steward, who may or may not be the same individual as Ravnunge-Tue (Lerche Nielsen Reference Lerche Nielsen2005: 20). The stones Læborg and Bække 1 that are connected to Ravnunge-Tue also refer to a certain “Thyra” or even “Queen Thyra”. Previous discussions of these stones have alternatively suggested a link between Jelling and the Bække-Læborg group or rejected such a connection, primarily based on whether or not the Thyra named on the stones is assumed to be the same individual (e.g. Magnusen Reference Magnusen1827: 119‒23; Kristensen Reference Kristensen1931: 635‒36; Jacobsen & Moltke Reference Jacobsen and Moltke1942: 52; Nielsen Reference Nielsen1954; Sawyer Reference Sawyer2000: 158‒66; Lerche Nielsen Reference Lerche Nielsen2005: 18‒19; Imer Reference Imer2016: 158‒72).

Figure 1. The Læborg stone. The stone is 236cm tall (photograph by Roberto Fortuna, National Museum of Denmark).

In this article, we investigate how historical, runological and linguistic sources in combination with analyses of carving techniques can bring us closer to the agents of the Jelling dynasty and the role of the queen. If a link between the stones of the Bække-Læborg group and Jelling can be established, for example, that some of the stones were carved by the same hand, it would be highly likely that the Thyra who is mentioned on all four stones is indeed the same individual. If so, the royal power of Jelling is extended to include other areas of Jutland, and more persons are added to the Jelling dynasty. The key to resolving this question is the Læborg stone, where the text explicitly names Ravnunge-Tue as the rune-carver with the phrase ‘cut these runes’. It also designates Thyra as Ravnunge-Tue's ‘queen’ (dróttning), which means that Thyra was an authority in relation to Ravnunge-Tue; the term dróttning encompassed women of royal descent as the female equivalent to dróttin ‘lord’ (Jacobsen & Moltke Reference Jacobsen and Moltke1942: 642).

Runestones in Denmark

Some 260 runestones are known from medieval Denmark including Scania and Schleswig, dating from the eighth century until c. 1100. More than half of these monuments were erected over two generations (about 50 years) following the conversion of Denmark to Christianity from c. 965 (Imer Reference Imer2015). Thus, the small number of runestones erected during the preceding decades of the tenth century were restricted to certain social circles, making it likely that the sponsors and carvers of the geographically neighbouring runestones of mid-west Jutland knew each other (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Locations of Danish runestones c. 900‒970. The analysed stones are marked with place-names (map by Rasmus Kruse Andreasen and Lisbeth M. Imer).

Runestones were carved granite manifestations of lineage and power erected at central places in the landscape: grave fields or grave mounds, ship-settings and crossroads. They were painted in bright colours and placed where leading families owned land and had certain administrative rights. The most common texts carved on these stones commemorate men and were expressed using a stable formulation: ‘X placed/erected this stone after (in commemoration of) Y, his father/brother/son’. Usually, only a single runestone was erected in memory of an individual but in some instances the sponsors of these runestones erected two monuments in different places. In the Danish tradition, it was more usual for women to erect runestones in commemoration of men, than vice versa. Fewer than 10 runestones known from pre-conversion Denmark were erected in commemoration of women, including the four stones that mention Thyra (Imer Reference Imer2016: 113, 169).

3D-scanning and groove analysis

To establish potential links between the four runestones that mention Thyra, we use 3D-scanning to assess whether we can identify the same runecarver's hand at work on all the stones. The carved surfaces of the five runestones that figure in the discussion of the Ravnunge-Tue group, as well as small sections of the Jelling stones, were 3D-scanned in September 2021 by Henrik Zedig. In addition, we also make use of the scans of the Jelling stones made in 2007 (Trudsø Reference Trudsø2010). To characterise the cutting of the runes, and identify whether they were carved by one or multiple hands, we use the method for groove analysis of runestones developed at the Archaeological Research Laboratory at Stockholm University (Freij Reference Freij1990; Kitzler Åhfeldt Reference Kitzler Åhfeldt2002), and which has been further developed and applied to various research questions about rune-carvers’ work organisation, mobility and related issues (e.g. Kitzler Åhfeldt Reference Kitzler Åhfeldt2016, Reference Kitzler Åhfeldt2019; Kitzler Åhfeldt & Imer Reference Kitzler Åhfeldt and Imer2019). The method consists of two parts: the first concerns the technical procedures used to record the variables; the second focuses on interpretation guided by experimental studies. The method is based on the premise that carvers practising their craft, like any craftworkers, develop their own individual motor performance (Kitzler Åhfeldt Reference Kitzler Åhfeldt2002: 8). This means that, with time and experience, they develop their own distinctive ways of working, which in turn creates a personal signature in the rune grooves. Below, we provide an outline of the analysis; more technical details are provided in the online supplementary materials (OSM).

Sampling strategy

The sampling strategy focused on identifying grooves that are well preserved (e.g. unweathered) and representative of each carved runestone as a whole (Figure 3). The carved surfaces were examined in the field and then scanned to produce digital 3D-models (see OSM for details). The number of individual runes recorded varied according to the size and condition of the stones and priority was given to grooves that are not intersected by other grooves (Figure 4). We documented between 8 and 38 individual runes for each stone, for a total of 129 runes from the seven runestones (Table S2; Figure 5).

Figure 3. 3D-model of a section of Læborg-stone: þurui : trutnik : sina ‘Thyra, his queen’ (3D-scanning by Henrik Zedig).

Figure 4. The function Groove Measure applied to a t-rune on the 3D-model of Læborg. The white label shown is 30mm long. We avoid the part where the groove flattens towards the end and joins the branches. We also avoid the lower part of the stave that is disturbed by a crack in the stone (image by Laila Kitzler Åhfeldt).

Figure 5. Jelling 2 with runes chosen for analysis. (3D-scanning by Zebicon, drawing by Laila Kitzler Åhfeldt).

Calculation of variables

To measure the grooves, we have applied a software tool created for this specific purpose: Groove Measure (see details in OSM). A number of variables are used to describe the shape of the incised grooves (Figure 6). Some refer to the cross-section, while others help to characterise the cutting rhythm by recording variation in the base of the groove along the cutting direction. The latter describes the sequence of pits created as the carver strikes on the chisel. Studies have shown that regular spacing of these pits indicates the hand of an experienced carver, while irregularity suggests the work of a novice (Kitzler Åhfeldt Reference Kitzler Åhfeldt2002: 92).

Figure 6. Graphs showing variables that describe variations in groove depth, groove angle and in the direction of cutting (illustration by Laila Kitzler Åhfeldt).

The groove angle (v), the ideal depth (D), an index for the cutting rhythm (k) and the mean distance between pits in the groove base (w = wavelength) are the most important variables for characterising each groove and how it was carved (Figure 6; see OSM for an explanation of D).

Experience from earlier studies

Experimental carving studies have been an integral part of the development of the method, including the investigation of runes carved by modern stoneworkers striving to achieve authenticity of practice and product in the context of historical re-enactment. These modern runestones allow us to assess the variation created by different individual carvers using various tool sets, sometimes sharing the same tools, and who have a range of skills from novice to experienced carvers. In addition, we can follow the development in skill over time of some individuals.

In addition, for comparative purposes, we also make use of some eleventh-century carvings from Sweden, as this material is more abundant and better understood; for example, the master carver Asmund Karason mentions several apprentices who assisted with the carving of runestones (Källström Reference Källström2007: 279‒89; Kitzler Åhfeldt Reference Kitzler Åhfeldt2016), which provide evidence for the variability of individual hands of different expertise.

Analysis

The Ravnunge-Tue group

The groove data extracted from the 3D models were analysed using statistical methods (for general statistical applications in archaeology, see Baxter Reference Baxter2003). Our first impression is that the variation within the Ravnunge-Tue group is large, the groove angle (v) covers the range 101‒144° and the ideal depth (D) of the grooves varies between 1.8mm and 4.9mm (OSM Table S2). Figure 7 shows that the stones plot with one central group and two separate outliers. Bække 1, Horne and Randbøl are the most similar stones, clustering as a group, with the considerably deeper grooves of the Læborg runes plotting to the lower left and the shallower runes of Bække 2, at the top right.

Figure 7. Groove angle diagram. Each dot in the diagram represents the runes on one runestone. The x-axis shows the variation in the groove angle, the y-axis shows the variation in depth (graph by Laila Kitzler Åhfeldt).

Comparison with stones by known carvers

To discuss the Ravnunge-Tue stones further, we need to place them in context. Here, we compare them with work by four carvers, two historical and two contemporary, each represented by two stones. These comparative examples comprise recently cut runestones by the Danish rune-carver Erik Sandquist (stones E1 and E2) and by the Swedish carver Kalle Dahlberg (K1 and K2), both rune-carvers of considerable experience (Kitzler Åhfeldt Reference Kitzler Åhfeldt2002: 35‒6). The historical examples comprise two eleventh-century runestones by Asmund Karason, signed by him alone (Jansson Reference Jansson1981: Gs 11 and Wessén & Jansson Reference Wessén and Jansson1940–1958: U 356), and two stones also from the eleventh century signed by Fastulv (U 170) and Faste (U 171), but probably referring to the same carver (Källström Reference Källström2013). By plotting the groove angles of the runestones cut by each carver, we can see the relatively distinct working style of each individual (Figure 8).

Figure 8. The stones in the Ravnunge-Tue group compared with runestones by other known carvers, showing the range and the median value for the groove angle for each runestone (graph by Laila Kitzler Åhfeldt).

Comparison with the Asmund group

In the box plot (Figure 8) on the right, there are five stones carved by Asmund and his assistants. Two of these carvings have been signed by Asmund alone (Gs 11 and U 356), one presumably by young Asmund and his own master Sven (Gs 13) and the remaining two stones by Asmund and an apprentice (U 1142 with Vigmar and U 1144 with Herjar). This is an example of a group of stones carved in the same Viking workshop, including a master and several apprentices. The Ravnunge-Tue group is similar to the Asmund group because the variation in the groove angle is of the same magnitude or even greater (Figure 8, left). The two stones signed by Asmund alone (Gs 11 and U 356) are similar to each other, while the three stones that are signed by two carvers (Gs 13, U 1142, U 1144) all have a shallower groove angle. The latter indicates that a less experienced hand has participated in the carving; because the novice typically has a less effective technique, less stone material is removed and the grooves are shallower. (Kitzler Åhfeldt Reference Kitzler Åhfeldt2002: 32). When comparing the variation within the Ravnunge-Tue group with that of the Asmund group (OSM: Table S3), we therefore argue that it indicates that the Ravnunge-Tue group also includes more than one carver.

Ravnunge-Tue and the Jelling stones

Next, we examine how the runestones at Jelling relate to the stones in the Ravnunge-Tue group. The runes on the Læborg stone are deep and narrow, and are matched by those on the larger Jelling stone (Jelling 2; OSM Table S2). Our experimental studies, however, show that to distinguish between individual carvers, it is essential to consider both the cross-section and the variation in the groove base along the cutting direction (Kitzler Åhfeldt Reference Kitzler Åhfeldt2002: Paper V). The clearest results are achieved when both aspects can be weighed together within multivariate analyses (e.g. Baxter Reference Baxter2003). Here, we use principal components analysis (PCA).

Principal components analysis (PCA)

The PCA considers the impact of the variables v (groove angle), D (ideal depth), k (rhythm index) and w (distance between pits) and reduces them to two dimensions; Factor 1 refers to the shape of the cross-section and Factor 2 refers to the cutting rhythm. In Figure 9, each dot represents a single rune. Again, we find Bække 1, Horne and Randbøl plotting together in the middle, while Bække 2 deviates from the others. Notably, the runes from Jelling 2 overlap with those from Læborg, with the exception of some outliers that we have retained as potentially representing poorly sampled subgroups (Kitzler Åhfeldt Reference Kitzler Åhfeldt2002: Paper IV: 141). The PCA plot indicates that the grooves of Læborg and Jelling 2 are similar to each other not only in the cross-section but also in terms of the cutting direction, which has proven essential in the identification of individual carvers. Jelling 1 is more similar to Bække 2, though the carved surface of Jelling 1 is less well preserved due to weathering.

Figure 9. Principal components analysis: Factor 1 refers to the shape of the cross-section; Factor 2 reflects cutting rhythm (graph by Laila Kitzler Åhfeldt).

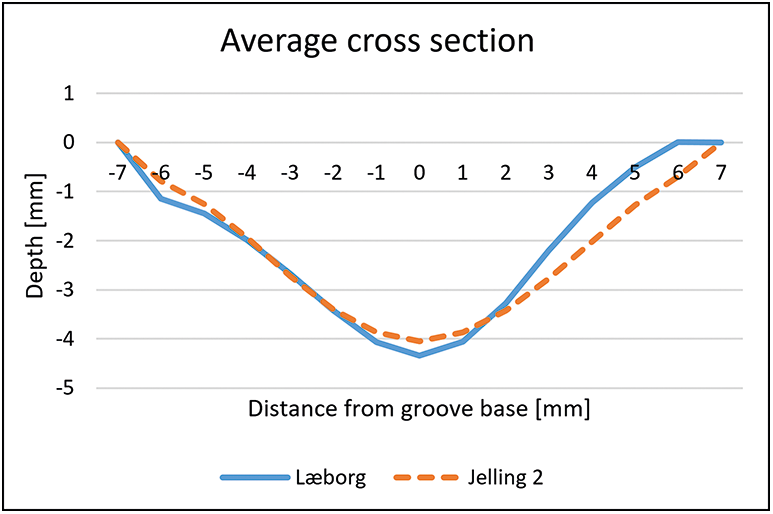

In addition, we have examined similarity between the stones using the multivariate methods of discriminant analysis and hierarchical cluster analysis, both of which seem to confirm the results of the PCA (see OSM). Strictly speaking, we examine the relative distances between the examined stones. Finally, to compare the actual appearance of the grooves, we examined ‘average cross-sections’ of the runes on Læborg and Jelling 2 (Figure 10). These averages are calculated using all the sampled runes on each respective stone (Læborg: 17 runes, Jelling 2: 38 runes). This shows that the average depths of the runes are similar, though the average width of the Læborg runes is approximately 1mm narrower. We deem these runes to be unexpectedly similar. Our initial assessment of the ornament cutting on the Læborg and Jelling 2 stones also points to strong similarities, though here we have chosen to concentrate specifically on the runes.

Figure 10. Average cross-sections of Læborg and Jelling 2 (graph by Laila Kitzler Åhfeldt).

Sources of error

One potential source of error in the application of the above method is the differential weathering of the stones’ surfaces, which may affect the depth and shape of the grooves. This problem has been acknowledged since the original development of the method (Kitzler Åhfeldt Reference Kitzler Åhfeldt2002: 36, Paper V) and has been tackled by focusing sampling on the best preserved and most intact grooves. Some variables are less vulnerable to weathering than others, and have been chosen accordingly. Another potential source of error relates to differences in the form of grooves carved into different types of stone of variable hardness and surface texture. It is to our advantage that all stones in the study are made of crystalline rock. The work of each individual carver may also vary due, for example, to growing skill, temporary fatigue or changing tools, all of which have been investigated in earlier studies (Kitzler Åhfeldt Reference Kitzler Åhfeldt2002). The rune grooves carved by experienced craftspeople are more consistent than those made by novices. The latter are therefore more difficult to characterise as individual carvers (Kitzler Åhfeldt Reference Kitzler Åhfeldt2002: 33, Paper V).

Our interpretation of individual hands builds on comparisons both with recently cut runestones and with authentic Viking-Age runestones (those of Asmund Karason). Nevertheless, instead of individual carvers, it might be wise to discuss the identification of analytical groups. The grooves of the Læborg and Jelling 2 runes are similar to one another, but on the basis of the 3D-scans we cannot prove that they were carved by the same hand. In our opinion, comparisons of groove shape with our reference data and with previous studies support our interpretation of individual carvers, but these conclusions also rest on typological analyses of the runes and their orthography, which we discuss in the following section.

Typology of runes, language and orthography

The distribution of the stones shown on Figure 7, with a central group and two outliers, is based on carving technique; the same grouping is supported by similarities in the typology of the runes and orthography/language. Most runestones in tenth-century Denmark were written with the 16-character, long-branch younger futhark, a stable runic alphabet with little variation or possibility of variation. A trained rune-carver, however, may have had their own style or ductus (i.e. direction, sequence outline with which the runes were carved (Imer Reference Imer2016: 58)), which means that variation occurs in the design or outline of each runic character. For example, a b-rune may have small or large pockets and their position on the main stave may vary. In the same way, branches may be short or long, they may be straight or curved, and their position on the main stave may vary.

Some of the characters in the 16-character futhark were used to express similar sounds (e.g. Imer Reference Imer2016: 34), which means that little linguistic variation is visible in the texts. Some variation occurs, however, in a few runestone texts that demonstrate a difference in language or orthography. Some of these variations are chronological. For instance, a diphthong in a word (þausi instead of þusi) is an older linguistic trait or an expression of a more conservative orthography; the same applies to the retention of /h/ before /l/, /n/ and /r/, which means that the spelling hrafn is older, or more conservative, than rafn. Other orthographic variations are not chronological, but rather seem to be expressions of personal taste or ability; for example, the omission of runes in individual words.

The groove analysis presented above demonstrates that Bække 2 is different from all the other stones. The same result is reached in terms of rune forms, orthography and linguistic traits. The runes on Bække 2 are rather small (100‒105mm in height; see OSM Figure S20) and irregular, and there seems to be no fixed pattern for the outline of each individual rune (see OSM Table S4). For instance, the pockets of the b-runes are sometimes placed on the middle of the main stave, and sometimes the lower pocket is placed at the lower end of the stave. Generally, there is a gap between the two pockets. The r-runes and u-runes also demonstrate irregularities. Compared with other stones, the branches of the Bække 2 runes are rather short, especially the f-rune. Some runes are placed closer together than others, which suggests that the inscription was poorly planned. Most words are carved in an abbreviated form, which also distinguishes the inscription from the other stones. These abbreviations hamper a comparison of linguistic traits, although the form of hribną:tubi Hrafnunga-Tófi seems to demonstrate a conservative spelling, and perhaps older linguistic traits, in the retention of the initial /hr-/ in hribną Hrafnunga- and the use of the b-rune instead of an f-rune in the name Tófi. The carving technique, specifically the groove angle, does suggest similarity between Bække 2 and Jelling 1, but as Jelling 1 is badly weathered this is uncertain; moreover, nor are there shared stylistic traits in the runes and orthography. In contrast, the spacing of the inscription on Jelling 1 is well planned, there are no abbreviations, the variation of rune forms is minor, the runes are much taller (160–290mm in height) and the language shows no older traits.

Bække 1, Horne and Randbøl form a group. The height of the runes in this group falls within the same range and there is little variation in their shape. The Horne runes are somewhat irregular in form, possibly due to the limited available space, and the carving of the Randbøl runes may have been affected by the rough surface of the stone. The b-runes on Bække 1 and Randbøl are similar (Horne has no b-rune), in that the pockets are placed towards the middle of the stave. The þ-runes on Horne and Bække 1 are rather large compared with other stones. The f-runes on all three stones are similar, in that the branches are not parallel. On all three stones, the branches on the u-rune may start from the top or a little below the top. Where comparable runes are present (e.g. the s-rune and m-rune are only present on the Randbøl), all the other rune forms are similar on the three stones.

Bække 1 and Horne both mention the raising or making of mounds. The spellings of the word ‘made’ (kaþi and kaþu instead of karþi and karþu, i.e. with the omission of the r-rune) are similar, leading scholars to suggest that the same individual could have carved both stones (Wimmer Reference Wimmer1899‒1901: 50, 57; Jacobsen & Moltke Reference Jacobsen and Moltke1942: 931). Indeed, these are the only two stones from Viking-Age Denmark with that particular spelling. The text on Randbøl is different from the other two and it shows no comparable linguistic traits.

On Bække 1, the name Ravnunge-Tue is spelled rafnuka:tufi, but on the fragmentary Horne stone, the first part of the inscription is missing …fnukatufi. The Bække 1 spelling is different from the Læborg stone: rhafnukatufi. These variations, paired with differences in the carving techniques, make it unlikely that Bække 1 and Horne were carved by the same individual as Læborg. Thus, they are presumably not the earlier works of Ravnunge-Tue and should probably be viewed instead as the works of an apprentice or colleague.

Læborg and Jelling 2 share similar traits that differentiate them from the other stones. The runes on these two stones are tall (Læborg 195–220mm, Jelling 2 145–250mm) and the main staves are notably straight. Generally, the branches of the runes are of the same length and are placed at the same height. For instance, the pockets of the þ- and b-runes are of equal size and position. The branches of the f-runes run parallel and there are two variants of r-runes; they may be wide or more narrow. The branches on the narrow r-runes tend to bend in towards the main stave on both stones. The shape of the u-runes on Læborg vary more than on Jelling 2, especially on side A, where the surface of the stone is more uneven.

The language used on Læborg and Jelling 2 is conservative (e.g. Moltke Reference Moltke1985: 201; Jesch Reference Jesch and Gammeltoft2013: 8‒9) and Læborg may even demonstrate Jutlandic traits: the verb haggva has the past tense form hjó (instead of hiogg), which is also found on other runestones and in medieval texts from Jutland (Brøndum-Nielsen Reference Brøndum-Nielsen1971: 226‒7; Lerche Nielsen Reference Lerche Nielsen2001: 240). The verb hjó is spelled hiau, probably a linguistically old trait with a diphthong, although it could also be viewed as a digraphic spelling of the value /o/ (Brøndum-Nielsen Reference Brøndum-Nielsen1971: 226‒7). Digraphic spelling, usually viewed as a conservative practice, also appears on Jelling 2 in the words kaurua ‘make’, þausi ‘these’, þąurui ‘Thyra’, and tanmaurk ‘Denmark’. In the Læborg text, the name Ravnunge-Tue is spelled rhafnukatufi Hrafnunga-Tófi, that is, with the retention of /hr-/ in the compound Hrafn-. This is also viewed as an archaic or conservative trait (Jacobsen & Moltke Reference Jacobsen and Moltke1942: 787; Lerche Nielsen Reference Lerche Nielsen2001: 240, Reference Lerche Nielsen2005: 14). It seems odd, however, that the spelling of Thyra's name differs between Læborg and Jelling 2. The Læborg inscription is þurui, Jelling 2 is þąurui. This may relate to the fact that the Jelling text is demonstrably archaic regarding the language, possibly ordered by the king to increase the prestige and authority of this official message (cf. Jesch Reference Jesch and Gammeltoft2013: 9).

The carved surface of the Jelling 1 stone is very worn, making the groove analysis difficult. The runes are particularly tall (up to 290mm) and the main staves are notably straight. In general, the shapes of the runes resemble those of Jelling 2 and Læborg. There are two r-runes, narrow and wide, and the lower branch of the narrow r-rune tends to curve in towards the main stave as on Jelling 2 and Læborg. The pockets of the m-rune are rounded and of equal size. Although Jelling 1 was probably erected a few years before Jelling 2, it does not show the same conservative orthography. Jelling 1 has the monophthongised þurui and þusi (accusative neuter plural) as on Læborg (þasi, accusative feminine plural) and tanmarkaʀ (genitive) as opposed to Jelling 2 tanmaurk (accusative). From a typological perspective, Jelling 1 resembles Læborg and Jelling 2 more than any of the other stones. This typological similarity, however, is not supported by the groove analysis.

Conclusion

The combined results of three independent methods suggest that a series of runestones from Viking-Age Denmark represent different rune-carvers working in the area around Jelling. All of the analyses point in the same direction, suggesting that Ravnunge-Tue carved the Læborg and Jelling 2 stones, whereas the Horne, Bække 1 and possibly Randbøl stones were carved by another hand. Bække 2 is an outlier and the analyses indicate that it was carved by an inexperienced craftsperson; the surface of Jelling 1 is too damaged for our groove analyses to draw any firm conclusions. Thus, by linking the Læborg stone to the Jelling complex, our investigation suggests that Thyra, mentioned on Bække 1 and commemorated on the Læborg stone and both Jelling stones, is the same person. The mentioning of Thyra on no fewer than four runestones is unparalleled in Viking-Age Denmark. In comparison, it is remarkable that Gorm is named on only a single stone (Jelling 2) —and there accompanied by Thyra. Not even her famous son, Harald Bluetooth, is mentioned on that many stones.

If we accept that runestones were granite manifestations of status, lineage and power, we may suggest that Thyra was indeed of royal, Jutlandic descent. Both Gorm and Harald refer to her in the runestone texts and Ravnunge-Tue describes her as his dróttning, that is, ‘lady’ or ‘queen’. Combined with the designation of Thyra as Danmarkaʀ bót, ‘Denmark's strength/salvation’ (Olsen Reference Olsen2012), these honours point towards a powerful woman who held status, land and authority in her own right. The combination of the present analyses and the geographical distribution of the runestones indicates that Thyra was one of the key figures—or even the key figure—for the assembling of the Danish realm, in which she herself may have played an active part. The analyses also reopen the question of who was buried in the (larger and more central) north mound at Jelling. The evidence presented here tends to support the traditional association with Thyra rather than the more recent assumption of Gorm; the latter's role, based on the runestone evidence, seems to have been of lesser importance. The foundation for these conclusions is the 3D-scanning of the runestones, combined with analyses of carving technique and the forms of runes and language used. The method shows a new and fruitful archaeological approach for the analysis of power and patronage in past societies, even when written sources are few or lacking.

Acknowledgements

By courtesy of Klaus Støttrup Jensen at National Museum of Denmark, the 3D-scans of the Jelling stones from 2007 were used in the analysis. This study was made feasible by KrogagerFonden, National Museum of Denmark and Swedish National Heritage Board.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.15184/aqy.2023.108.