Estuaries and coastal marshes are among the most productive, diverse and threatened ecosystems on earth. Archaeologists often assume that the productivity of estuaries, and their attractiveness to humans, increased significantly during the Mid-Holocene as sea-level rise slowed (Day et al. Reference Day, Gunn, Folan, Yáñez-Arancibia and Horton2012: 26), fostering a florescence of coastal settlement and estuarine resource use. In some areas (e.g. San Francisco Bay) this is true, but rapid post-glacial sea-level rise created numerous earlier estuaries by flooding the mouths of coastal drainages (Graham et al. Reference Graham, Dayton and Erlandson2003). For coastlines adjacent to broad continental shelves, such estuaries would have been located far from modern shorelines, and archaeological evidence for their use is probably submerged far offshore. On relatively steep and narrow continental shelves such as those of the Pacific Coast of the Americas, however, early post-glacial estuaries would have been located much closer to the modern coast, and archaeological evidence for their existence is more likely to be discovered.

The Pleistocene–Holocene transition was a time of major ecological change, when global climatic regimes shifted from glacial to interglacial conditions and rapidly rising seas flooded continental shelves, with major ramifications for global geography and biodiversity. Humans first colonised the Americas at this time, probably between 20 000–15 000 years ago. For most of the twentieth century, archaeologists focused on the interior ‘ice-free corridor’ as the entry route for the First Americans, with these Palaeoindians viewed as big-game hunters who preyed primarily on mammoths, mastodons, bison and other large mammals.

For decades, evidence for human occupation of New World coastal zones lagged behind interior regions, with little evidence for human use of coastal resources earlier than 9000–10 000 cal BP. Archaeological and genomic discoveries have closed this gap, shifting the focus to the Pacific Coast as the most probable dispersal route for the First Americans (Braje et al. Reference Braje, Dillehay, Erlandson, Klein and Rick2017). The ‘kelp highway’ hypothesis proposes that the ecological similarity and biodiversity of Pacific Rim kelp forests may have facilitated the dispersal of maritime peoples from North-east Asia to the Americas (Erlandson et al. Reference Erlandson, Graham, Bourque, Corbett, Estes and Steneck2007). Pacific Coast estuaries also contained productive and species-rich habitats, however, including anadromous fish runs that may have led people deep into continental interiors.

As more and earlier coastal sites have been identified in the Americas, interest has grown in how Palaeoindians interacted with and affected coastal ecosystems. On California's Santa Rosa Island, we have identified evidence for human use of estuarine shellfish and coastal marsh resources 11 800–11 100 years ago, extending the use of such ecosystems in Alta California by nearly two millennia.

Santa Rosa Island is one of four northern Channel Islands, formerly united as one large island (Santarosae) before rising seas separated them 11 000–9000 years ago (Figure 1). Separated from the mainland by a 6–8km-wide strait, Santarosae was 125km long, with a land area roughly four times the size of the modern northern Channel Islands. Until 9000 years ago, the 8km-wide Santa Cruz Channel that now separates Santa Rosa and Santa Cruz islands was broad lowland, with a land bridge to the north and a south-facing embayment (Crescent Bay) to the south. At the centre of Crescent Bay was a deep submarine canyon, into which flowed several of Santarosae's largest drainages. Today, there are no estuaries on the northern Channel Islands, but archaeological and palaeoecological data show that an estuary existed on south-eastern Santa Rosa Island between 8500 and 5000 years ago (Rick et al. Reference Rick, Kennett, Erlandson, Garcelon and Schwemm2005). Pollen cores in the area document a transition from estuarine to freshwater marsh habitats over the past 7000–6000 years (Anderson et al. Reference Anderson, Starratt, Brunner Jass and Pinter2009).

Figure 1. The location and palaeogeography of California's northern Channel Islands (palaeoshoreline estimate does not account for post-transgressive sediments deposited offshore).

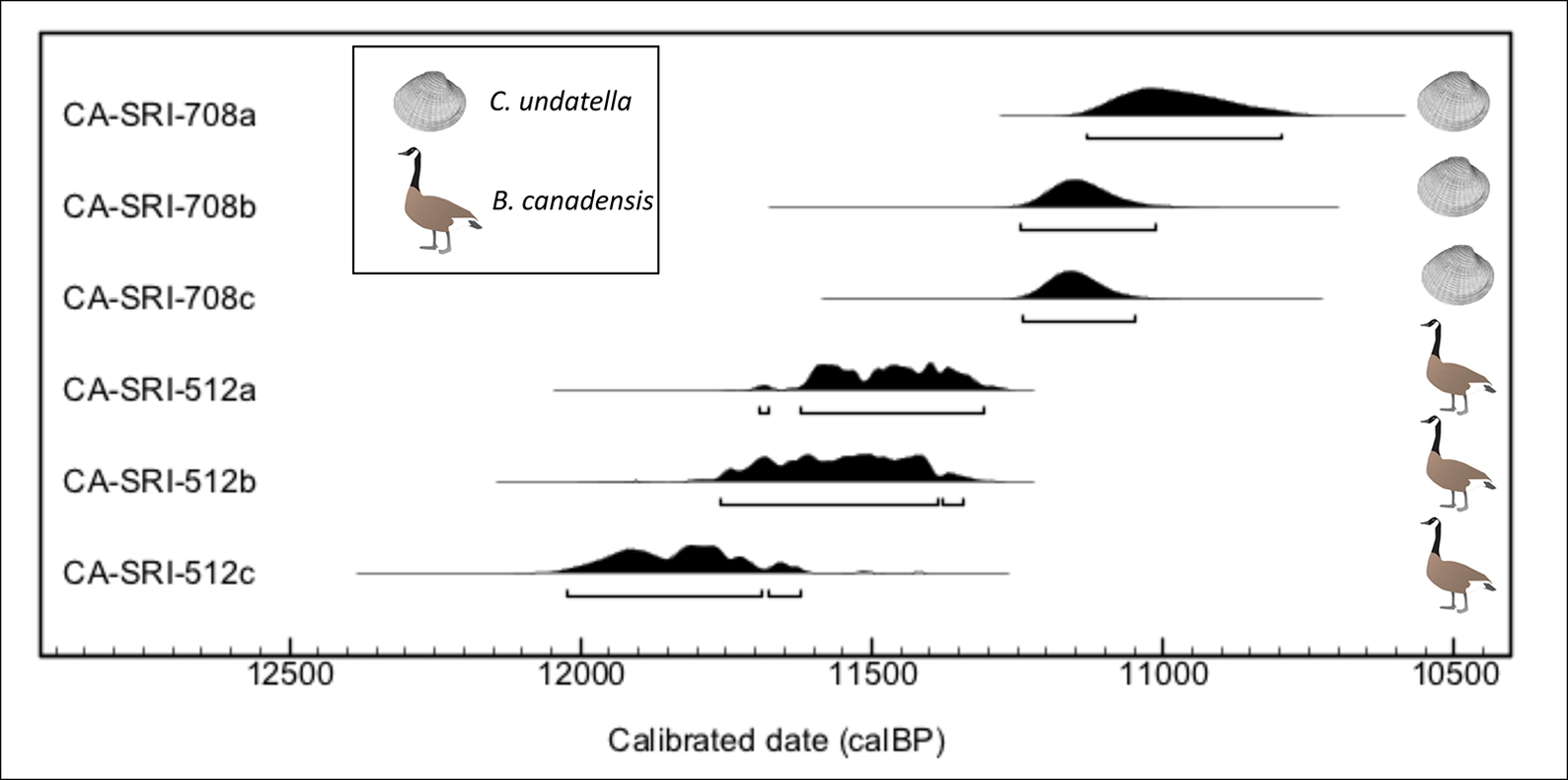

In 2011, we recorded a shell midden (CA-SRI-708) on eastern Santa Rosa Island that contains Palaeocoastal components dated between 11 300 and 9000 years ago. Excavation of Palaeocoastal midden deposits produced large quantities of rocky intertidal California mussels (Mytilus californianus), smaller amounts of estuarine shellfish and more than 600 bird-bone fragments from waterfowl (geese/ducks). From this Palaeocoastal component, three shells of the estuarine Venus clam (Chione undatella) produced AMS radiocarbon dates of 10 255±40 BP, 10 400±45 BP and 10 410±35 BP, harvested between 11 300–10 850 cal BP (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Calibrated radiocarbon age ranges for estuarine and coastal marsh resources from Santarosae archaeological sites (calibrated using OxCal 4.3 and the Marine13 curve for shell samples (ΔR 261±21) and the IntCal13 curve for bird bones, Bronk Ramsey (Reference Bronk Ramsey2009); Reimer et al. (Reference Reimer2013)).

Associated with these faunal remains were Channel Island Barbed points consistent with this period and chipped-stone crescents used as transverse projectile points for hunting birds. CA-SRI-512, a midden on Santa Rosa Island's north coast, produced similar Palaeocoastal artefacts, hundreds of waterfowl bones and six AMS radiocarbon dates (three on goose bones, three on charcoal) ranging from 12 000–11 350 cal BP (Erlandson et al. Reference Erlandson2011).

For Santa Rosa, archaeological data now indicate a sustained human harvest of kelp forest, rocky shore, and estuarine and marsh resources between at least 12 000 and 10 850 years ago, including intensive shellfishing, marine fishing and the hunting of migratory waterfowl and marine mammals. These aquatic resources complemented a wealth of carbohydrate-rich terrestrial plant foods on the island, especially edible geophytes (Gill Reference Gill2016).

On Baja California's Cedros Island, Des Lauriers (Reference Des Lauriers2010) also documented a maritime culture dating back nearly 12 000 years, including faunal assemblages with small amounts of estuarine clams (Chione spp.). People harvested fish and other resources from estuarine habitats at Huaca Prieta in Peru as early as 15 000 years ago (Dillehay et al. Reference Dillehay2017), and estuarine and marine seaweeds at Monte Verde II in Chile 14 000 years ago (Dillehay et al. Reference Dillehay, Ramírez, Pino, Collins, Rossen and & Pino-Navarro2008). McLaren et al. (Reference McLaren, Fedje, Dyck, Mackie, Gauvreau and Cohen2018) also documented 13 000-year-old human footprints in estuarine muds on a British Columbia beach.

Collectively, Pacific Coast archaeological data demonstrate that productive estuaries and marshes played a significant role in the peopling of the Americas. Tracking the evolution of these landscapes can help identify early coastal archaeological sites and evaluate the viability and timing of migrations into the New World. As research continues above and below the sea, further evidence for early estuarine resource use will probably emerge, especially in areas where narrow continental shelves are most likely to preserve evidence for early coastal foraging.

Acknowledgements

Our research was supported by the National Science Foundation (#BCS 0917677), Edna English Trust for Archaeological Research, UO Museum of Natural & Cultural History's Paleoindian Endowment and our home institutions. We thank Chumash consultants Mark Garcia, Paula Pugh and Alan Salazar for field support, and Ann Huston and Laura Kirn for logistical support.