Introduction

In the south-central Andes, links between hunter-gatherers, bofedales and salt flats date back to the late Pleistocene and persist during the Holocene (12.7–3.7 ka) (e.g. Santoro & Núñez Reference Santoro and Núñez1987; Capriles et al. Reference Capriles2018; Rademaker & Moore Reference Rademaker, Moore and Lemke2019). Bofedales are peat-forming wetlands restricted to elevations above 3800m above sea level (Squeo et al. Reference Squeo, Warner, Aravena and Espinoza2006) that support a diverse range of biota. These Andean wetlands were vital sources of food and raw materials for both hunter-gatherers and pastoralists, and various archaeological models identify them as axes of high-altitude mobility (e.g. Santoro & Núñez Reference Santoro and Núñez1987; Capriles & Tripcevich Reference Capriles and Tripcevich2016). Yet, further research is needed to understand the role of bofedales for hunter-gatherer groups; investigations have largely focused on scattered sites on a broad geographic scale—mainly attending to caves or rock shelters—and few landscape-scale surveys around bofedales have been developed. Archaeological sites have also typically been defined with little consideration of geomorphological place formation, leading to a static view of the archaeological record, which is understood on an ethnographic scale (like a dichotomy of residential versus logistical camps) and not as a more complex, emergent phenomenon (Holdaway & Davies Reference Holdaway and Davies2020). Therefore, our project aims to evaluate the economic, social and cultural interactions between hunter-gatherer groups, bofedales and salt flats by studying four areas around the Surire Salt Flat basin (S18°50′20″; W69°02′49″) (Figure 1). To move away from a one-dimensional characterisation of environment and material culture, we adopt a geoarchaeological approach considering the interaction of multiple natural and cultural processes operating at different temporal and spatial scales (Holdaway & Davies Reference Holdaway and Davies2020).

Figure 1. Study area: 1) main peaks of the Surire basin; 2) contour lines; 3) Altiplano basin; 5) Surire basin; 6) survey areas (C: Caracota, P: Parcohaylla, PS: Pampa Surire, BS: Bofedal de Surire); 7) national borders—represented here because current political borders had consequences for the distribution of pastoral archaeological sites in the twentieth century; 8) Chilean contemporary wetlands (figure by authors).

Methodology

The multiscalar geoarchaeological framework of the project is synthesised in Figure 2. To guarantee inclusion of a diversity of wetland areas, while taking field accessibility into account, we opted to investigate two bofedales (Parcohaylla and Bofedal de Surire), a seasonal lake (Caracota) and a portion of the southern border of the Salar de Surire Salt Flat basin. Two areas—Caracota and Bofedal de Surire—were geomorphologically mapped at a medium scale, and a chronostratigraphic study of the main landforms was carried out. To characterise surface archaeology and its spatial distribution, we used parallel transects spaced every 50m as survey units, and our focus was lithic artefacts. Technological characterisation focused on classification of lithic categories: cores, retouched artefacts (considering morpho-functional assumptions), projectile points, preforms and debitage products (flakes, blades, debris). After reviewing field recording forms and photos, we clarified technological categories and relative chronologies according to regional projectile point typologies (Santoro & Nuñez Reference Santoro and Núñez1987; Lefebvre Reference Lefebvre2004; Osorio et al. Reference Osorio2017). We also collected several surface lithic scatters in the two mapped areas to understand their behavioural dimensions, and dug test pits to expose the stratigraphy to understand place formation processes.

Figure 2. Geoarchaeological project framework (figure by authors).

Preliminary results

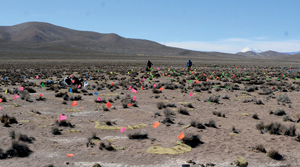

Hunter-gatherer occupations close to and within bofedales and palaeobofedales are attested in all the studied areas, especially in Bofedal de Surire and Caracota. Complex geomorphological histories affect the archaeological record; trajectories dominated by accumulation and/or erosion can co-exist in the same areas. In Caracota, we observe a seasonally dry lake with a relatively low sedimentary accumulation rate and palaeobofedales surfaces characterised by the active dynamics of erosion and deposition (Figure 3a). In Bofedal de Surire, lithic surface palimpsests are found above palaeobofedales surfaces, alongside old Pleistocene surfaces showing long-term accumulation of artefacts (Figure 3b).

Figure 3. A) Pleistocene aeolian deposits in Caracota with flags indicating lithic material; B) extended palaeobofedal in Bofedal de Surire with palimpsests of lithic materials (C) (figure by authors).

Lithic material density varies between 292 and 596/km2 for the two bofedales and Caracota lake, while it is 10/km2 along the southern border of the Surire Salt Flat. These variations could relate to cultural (e.g. recurrent occupation) and/or geomorphological factors. Lithic scatters showing different patterns in terms of density, raw materials, technology, projectile point typologies and local geomorphological histories were also identified. The formation and significance of these spatial patterns must be resolved by further field and laboratory analysis.

Projectile point typologies offer an initial chronological frame for human occupation in each area. Bofedal de Surire shows occupation by hunter-gatherer groups from the Late Pleistocene/Early Archaic until the Late Holocene (12.7ka–1 cal ka (i.e. at least the Tiwanaku period) (Figure 4). In the Caracota area, we recognised Late Pleistocene/Early Archaic, Middle Archaic and Late Archaic occupations. In Pampa Surire, we recorded Late Pleistocene/Early Archaic typologies (Figure 5), and types present in the complete chronological sequence. Overall, the materials recognised in these three areas suggest repeated occupation of places during the Holocene. Artefacts in Parcohaylla are more suggestive of occupation by agro-pastoralist communities.

Figure 4. Projectile points found during the study: A–F) Bofedal de Surire; G & H) Pampa Surire. A) Early Archaic; B) Late Archaic; C) Late Archaic-Formative; D) Late Pleistocene/Early Holocene; E) Late Archaic; F) Tiwanaku; G) Early Archaic/Middle Archaic; H) presence in whole sequence (figure by authors).

Figure 5. Projectile points from Caracota. A) Late Pleistocene/Early Archaic; B, C & E) Early Archaic; D) Middle Archaic; F) Middle Archaic; G & H) Late Archaic (figure by authors).

Perspectives

At the regional scale, bofedales formation seems to have occurred gradually throughout the Holocene (Gallardo et al. Reference Gallardo, Otto, Gayo and Sitzia2024; Otto et al. Reference Otto, Gallardo, Sitzia, Osorio and Gayo2024). Human occupation of bofedales is, therefore, also expected to differ according to local historical trajectories of landscapes. Based on preliminary field surveys, we further observe that larger bofedales were occupied by hunter-gatherers and agro-pastoralist societies, while smaller bofedales were used mainly by hunter-gatherer groups. As a preliminary hypothesis (requiring formal testing), we propose that bofedales size was a selection criterion for their use in managing animals in pastoralist groups.

The study of landscape formation from a geoarchaeological perspective is a fundamental step toward understanding the social dynamics different hunter-gatherer groups developed in the Andes. Topics such as land use, mobility and settlement systems, among others, cannot be addressed without understanding the geomorphological and geological history of the Dry Puna. The systematic perspective we propose should frame the archaeological record at appropriate temporal scales and allow us to build robust hypotheses and inferences about the medium to long dwell time of bofedales landscapes.

Funding statement

The project is founded by ANID – Chile projects Fondecyt Iniciación 11200212 and Fondecyt Postdoctorado 3210151.