Introduction

Recent archaeological studies conducted in Carangas (Figure 1), a region of the central-southern Andean Altiplano characterised by its extremely arid and cold climate, have revealed many pre-Hispanic religious sites and structures that form a dense ritual landscape. In particular, we identified a noteworthy set of 135 sites located on hilltops, most of which are directly associated with ancient agricultural production areas (Cruz & Joffre Reference Cruz and Joffre2020). These can be identified on the ground and in satellite images by their variable number of concentric walls (between two and nine per site), each of which occupies a different level of terrace around the hilltop (Figure 2).

Figure 1. Map showing the location of the Carangas region in Bolivia (credits: P. Cruz; map from Global Multi-Resolution Topography).

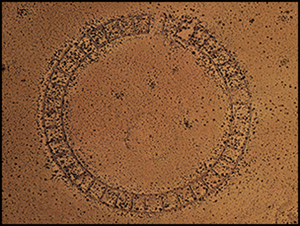

Figure 2. Photographs of the walled concentric sites in the Rio Lauca area of Carangas (credits: P. Cruz; from GoogleEarth images).

Abundant quantities of pre-Hispanic ceramic fragments are found at all sites. These are mostly of local styles typical of the Late Intermediate and Late Periods (AD 1250–1600) (Villanueva Criales Reference Villanueva Criales2015), along with some regional styles linked to the southern expansion of the Incas. Most of the ceramic fragments correspond to bowls, plates and small jars, indicating their use in commensal and ritual practices (Bray Reference Bray2003). Although these religious sites possess some of the same defensive characteristics as the pre-Hispanic occupation sites known as pukaras, we found no significant evidence that these were residential. These ceremonial spaces emerged during the Late Intermediate Period, like the pukaras, and were later appropriated and resignified by the Incas. The characteristics of these ceremonial spaces correspond with the information provided about wak'as and their shrines (Mannheim & Salas Carreño Reference Mannheim, Carreño and Bray2015) by Spanish clerics and chroniclers of the Colonial Period (AD 1535–1800), such as the famous Guaman Poma de Ayala (Reference Guaman Poma de Ayala1980 [1615]). The concentration of religious spaces in this region of the Altiplano may be explained by the belief that the tutelary divinities could regulate the already extreme climatic conditions, since a small variation in temperature or rainfall could cause the loss of all crops or the death of livestock.

In addition to these concentric-walled sites, we identified a completely different site, Waskiri, near the Lauca River and the Bolivian-Chilean border. It is an impressive circular construction, located on a small hill, which surprises both in its large dimensions (140m in diameter) and its design and regularity (Figure 3). The site has a perimeter ring comprising 39 adjoining enclosures, each with a surface area between 106 and 144m2. These enclose a plaza of approximately 1ha, which is scattered with abundant ceramic fragments ascribed to the Late Intermediate and Late Periods—similar to those observed in the hilltop concentric-circle sites. We found no structures or material remains that could be ascribed to either earlier or more recent periods. Two other circular constructions, 24m and 23m in diameter, are located respectively 40m and 255m outside the main site.

Figure 3. Photograph and site plan of Waskiri (credit: P. Cruz).

A ceremonial centre with unknown characteristics in the Andes

The pre-Hispanic ceremonial centre of Waskiri is not only a surprising discovery in this sparsely populated desert region of the Andes, but also exhibits characteristics that are unprecedented in the pre-Hispanic Andes. It is likely, however, that the first reference to the site is found in the chronicle of the evangelising priest Bartolomé Álvarez (Reference Álvarez1998 [1588]: 111), who travelled through the Carangas region during the 1580s. Álvarez received information about the existence of a ‘large circular building’, in which the main Indigenous authorities of the region, curacas and caciques, met to perform ceremonies for the Sun during the month of June—the Inti Raymi, one of the most important annual Incan ceremonies also described by Guaman Poma (Reference Guaman Poma de Ayala1980 [1615]: 175)—as well as for other religious celebrations, including animal sacrifices. The religious and political importance of these celebrations and sites was highlighted in the words of Álvarez (Reference Álvarez1998 [1588]: 111) when he described the attendees as entering a kind of “solemn drunkenness” in these highly particular buildings that he considered to be the “house and business of hell”.

Various aspects of the site are particularly relevant in relation to Alvarez's information. First, the design of the site, housing 39 perimeter enclosures distributed around a large central plaza, is consistent with the congregation of authorities and their retinues from different localities. Also, the location of Waskiri in a desert area, separate from any pre-Hispanic settlement or agricultural sector, may have factored into its use as a regional ceremonial centre, located in a neutral or common space. Regardless, Waskiri is centrally located within the religious cartography of the region, connected visually and spatially with the principal sacred mountains, numerous walled concentric sites, funerary towers ornamented with designs that replicate Inca textiles (Gisbert Reference Gisbert1994), and other geo-symbolic markers (Figures 4 & 5). In this sense, the radial design of the site and its linkage with the main religious landmarks of the region—all considered to be wak'as—mirrors the Incan ceque system, the paths that ordered the sacred geography in Cuzco, the capital of their empire (Zuidema Reference Zuidema1964). In fact, the radial walls that delimit the 39 enclosures around the perimeter of Waskiri reflect a structure that is very much akin to that of the Incan ceque of Cuzco. By arranging these according to the cardinal axes, four quadrants composed respectively by 9-9-9-8 walls or lines are observable, which is similar to the quadrants of the Cuzco system that is integrated by 9-9-9-14 ritual paths (Bauer Reference Bauer1992) (Figure 6). The intentionality of this arrangement is clearly expressed in wall 3 that delimits enclosures c and d of the south-west quadrant of Waskiri, which, unlike the other 34 walls, does not have a corresponding wall on the opposite side of the site. If the divisor walls of Waskiri did indeed represent a ceque system, this would be more explicit evidence that the Incas replicated the symbolic structure of Cuzco in the regions they colonised.

Figure 4. Top) view from Waskiri, showing the silhouettes of the main sacred mountains of the region; bottom) distribution of sacred sites around Waskiri (credits: P. Cruz).

Figure 5. Funerary towers of the Rio Lauca (credit: P. Cruz).

Figure 6. Comparison between the Waskiri site structure and the Cuzco ceque system (based on Bauer Reference Bauer1992; credit: Pablo Cruz).

Conclusion

This ceremonial centre and the ritual landscape in which Waskiri is situated provides rich material for further study of the pre-Hispanic history of this part of the Andes—an area that has been generally understudied. Further research will allow investigators to test these initial hypotheses and interpretations.

Acknowledgements

We thank the Institute of Anthropology and Archaeology of the UMSA (La Paz, Bolivia) and the Redes Andinas project for their support and collaboration.

Funding statement

We thank the French National Research Institute for Sustainable Development (IRD) for logistical support and funding.