Introduction

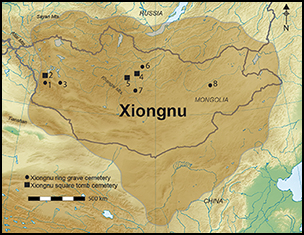

During the first millennium BC, the Inner Asian steppe exhibited increasingly ostentatious mortuary monuments that displayed the power of nomadic elites and facilitated the interregional consolidation of the Xiongnu steppe empire (c. 200 BC–AD 100) (Brosseder & Miller Reference Brosseder and Miller2011; Honeychurch Reference Honeychurch2015; Figure 1). While the construction and use of large mortuary structures undoubtedly shaped local political dynamics, shared practices reflected in burial structures and ritual activities across Inner Asia projected a potent association with the Xiongnu Empire and the overarching authority of its ruling echelon (Miller Reference Miller2011). Repetitive ritual activities served to legitimise and commemorate elite factions within the context of the multi-regional steppe polity, while simultaneously generating a corpus of social memories that linked individuals, both living and dead, with the ancestors of a constructed past and agendas of a political present (Johannesson Reference Johannesson2016). Here, we address peripheral features associated with Xiongnu burials, which, we argue, represent ritual practices that augmented mortuary ceremonies beyond the funerary rites of interment. Competitive commemorations and social reifications within communities of the Xiongnu Empire were thereby enhanced.

Figure 1 Ritual sites of Iron Age Inner Asia (Xiongnu realm shaded): 1) Shombuuzyn-belchir; 2) Takhiltyn-khotgor; 3) Baishin-uzuur; 4) Gol Mod; 5) Gol Mod 2; 6) Bugat; 7) Ar-bulan; 8) Ulaan-khanan (map by B. Miller).

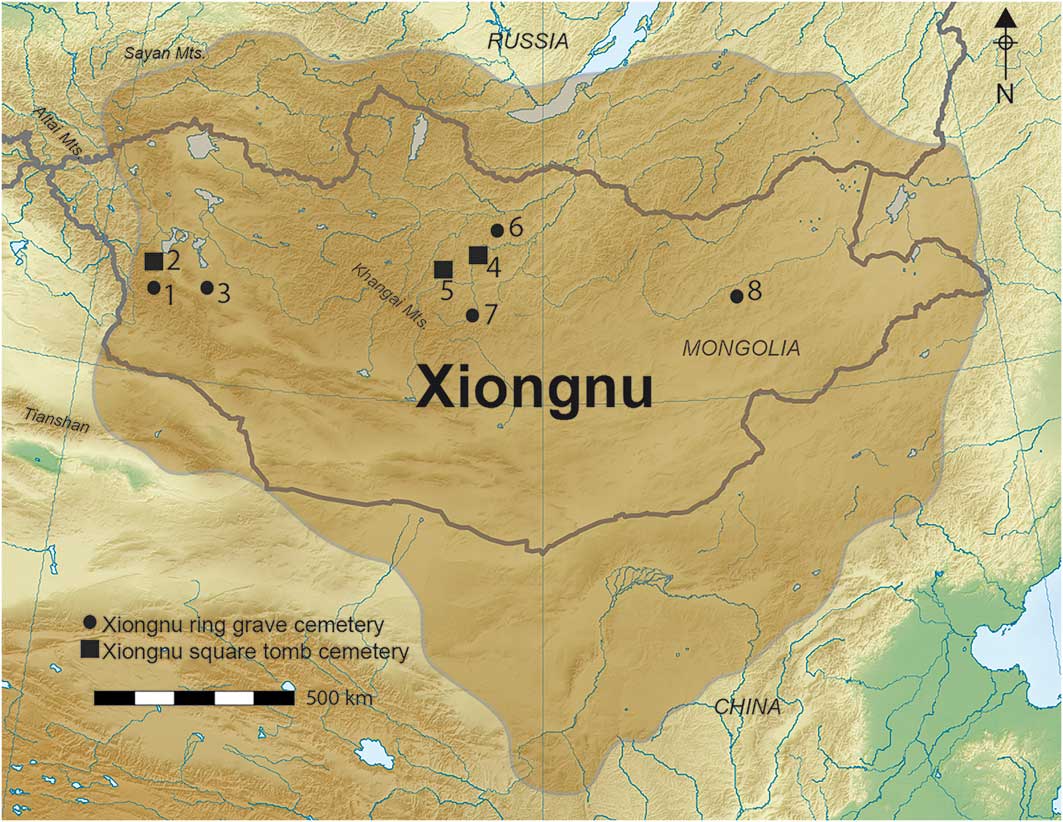

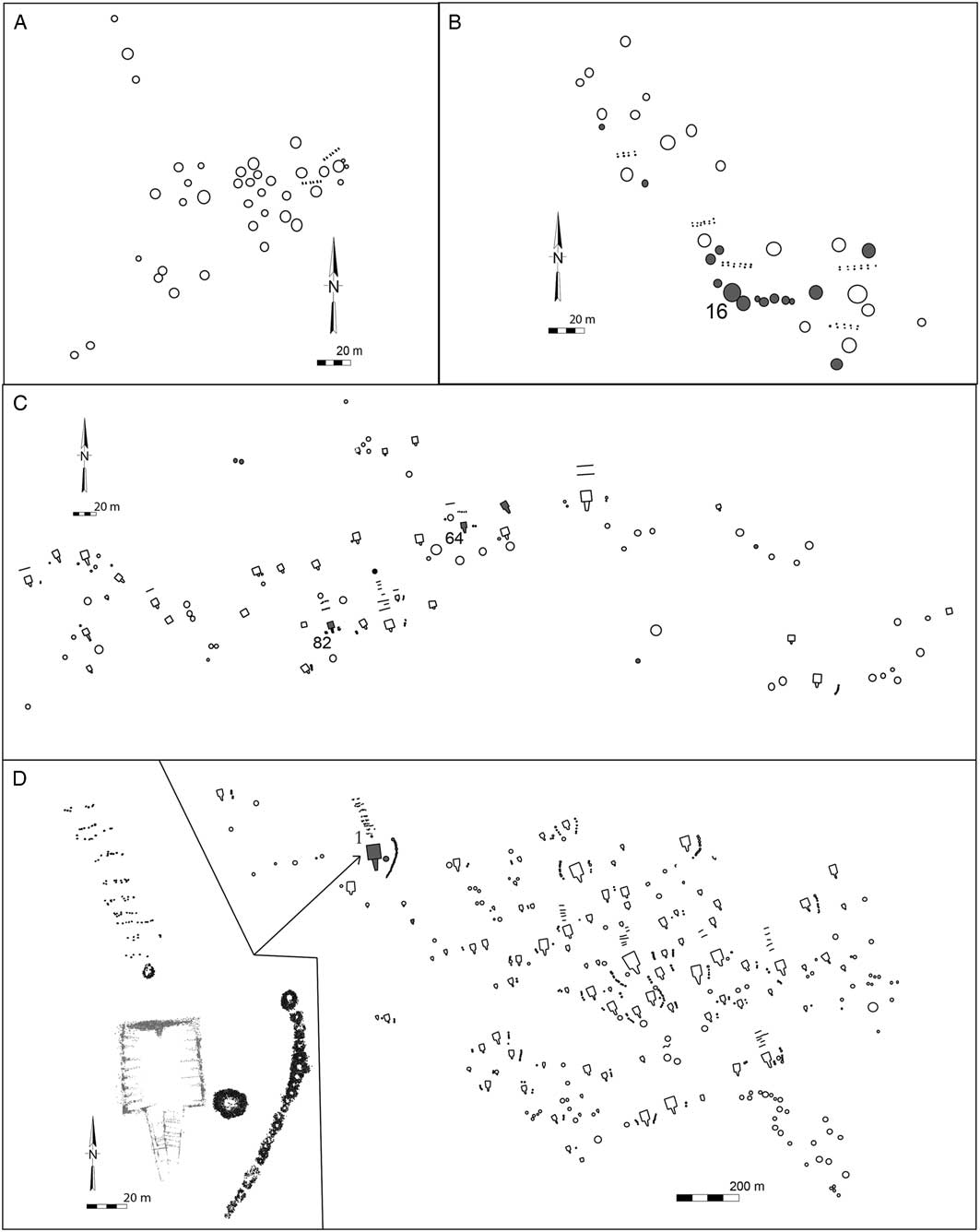

Quantitative and qualitative differences in grave furnishings demonstrate pronounced hierarchies in Xiongnu society. The majority of burials consist of thick stone-ring constructions on the ground surface above a shaft pit (approximately 1–3m deep) containing a rectangular coffin. The burials are often accompanied by skeletal elements from domestic animals. Broad variations in grave size, coffins and burial goods, however, indicate significant social gradations (Törbat Reference Törbat2004; Kradin Reference Kradin2005). In addition, a few Xiongnu cemeteries scattered across the empire feature radically different tombs. These comprise large, stone-lined, square earthen mounds with ramped entrances, and large pits (up to 20m in depth) containing wooden burial chambers with decorated coffins and exotic luxuries (Brosseder Reference Brosseder2009; Figures 2, 3, 8). Remains of livestock in these massive tombs were frequently augmented by large deposits of the heads and hooves of horses along with decorated chariots and horse ornaments of precious metals. Despite the centrality of animal remains in Xiongnu mortuary practices, the spectrum of offerings (numbers, taxa, post-mortem treatment) interred in these complexes constitutes one of the greatest—yet least explored—demonstrations of social politics.

Figure 2 Xiongnu cemeteries with stone lines (shading denotes excavated graves): A) Baishin-uzuur; B) Shombuuzyn-belchir (Bayarsaikhan et al. Reference Bayarsaikhan, Egiimaa, Miller, Konovalov, Johannesson, Machicek, Logan and Neily2011); C) Takhiltyn-khotgor (after Miller et al. Reference Miller, Baiarsaikhan, Egiimaa, Konovalov and Logan2009); D) Gol Mod 2 and GM2-1 tomb (after Allard et al. Reference Allard, Erdenebaatar, Batbold and Miller2002; Erdenebaatar et al. Reference Erdenebaatar, Iderkhangai, Mijiddorj, Orgilbayar, Batbold, Galbadrakh and Maratkhaan2015).

Figure 3 Xiongnu square tomb complexes with satellite graves and stone lines: A) Takhiltyn-khotgor 64; B) Takhiltyn-khotgor 82 (after Miller et al. Reference Miller, Baiarsaikhan, Egiimaa, Konovalov and Logan2009).

The use of livestock to commemorate the dead features prominently in the rituals of pastoral societies throughout the ancient world (Hanks Reference Hanks2002; Makarewicz Reference Makarewicz2010; McCorriston et al. Reference McCorriston, Harrower, Martin and Oches2012; di Lernia et al. Reference di Lernia, Tafuri, Gallinaro, Alhaique, Balasse, Cavorsi, Fullagar, Mercuri, Perego and Zerboni2013). Through their employment in mortuary rituals, livestock may have served as means of costly signalling (cf. Plourde Reference Plourde2009; Wright Reference Wright2017), a way to reify social relations (Hayden Reference Hayden2009; Insoll Reference Insoll2010). In Xiongnu cemeteries, rites of social commemoration operated on both regional (polity) and local (community) scales (Johannesson Reference Johannesson2016). Analysis of multiscalar ritual practices demands attention to patterns of inter- and intra-cemetery rites, as well as variations between practices within individual mortuary monuments. The prevalence of domesticated animal remains adjacent to, or within, Xiongnu graves not only reflects the primarily pastoral orientation of the Xiongnu economy, but also strongly suggests that animal sacrifice constituted a central component of Xiongnu mortuary customs, and intimates a corpus of beliefs centred on livestock (Crubézy et al. Reference Crubézy, Verdier, Maureille, Erdenebaatar, Batsaikhan, Giscard and Martin1996; Makarewicz Reference Makarewicz2011; Martin Reference Martin2011).

Animal remains in Xiongnu graves typically include the skulls, extremities and, occasionally, the ribs and caudal vertebrae of sheep, goat, cattle and horse (Crubézy et al. Reference Crubézy, Verdier, Maureille, Erdenebaatar, Batsaikhan, Giscard and Martin1996). Demonstrable inter- and intra-cemetery variation exists between species, the number of animals, body-part representation and spatial placement within graves (e.g. Törbat Reference Törbat2004: 74–76; Makarewicz Reference Makarewicz2010). Although the vast majority of Xiongnu graves were looted in antiquity, it is mostly the human interments and the contents of coffins that were most heavily disturbed or even completely removed. In contrast, animal remains, placed outside of the coffins, are largely intact, thereby providing faunal samples suitable for investigating the role of animals in funerary practices. Faunal remains found in Xiongnu mortuary arenas represent the remnants of the final stage of the ritual practices of sacrifice and offering conducted at sites. Animals were taken from valued herds and given up for specific ritual purposes; in other words, they were sacrificed. Through sacrificial processes of selection, destruction (killing) and apportion, animals were then offered—or given to—living participants at funerals, or to the deceased occupants of burials. The animals may even have been offered in reference to other entities, including collective ancestors or spirits. Nevertheless, the particular mechanisms and phases of animal sacrifice (cf. Valeri Reference Valeri1994; Insoll Reference Insoll2010) have been seldom investigated at Xiongnu cemeteries. While livestock remains placed alongside primary human interments formed a prominent component of Xiongnu funerary rites, they comprised only one milieu of animal-based ritual practices conducted within Xiongnu mortuary arenas.

Although burials have been the focus of much archaeological research on the Xiongnu, recent fieldwork at the Mongolian Altai sites of Takhiltyn-khotgor (THL) and Shombuuzyn-belchir (SBR) has unearthed small features external to, but in direct association with, Xiongnu graves, that are indicative of ritual elaboration beyond the primary interment event (Bayarsaikhan & Miller Reference Bayarsaikhan and Miller2008). Ash, charcoal and burnt animal bone fragments set between paired stones have been recovered from lines of such stones associated with square tombs and standard ring burials. Along with the presence of small circular graves flanking some of the square tombs, stone lines laid out beyond the central burial pits expand the mortuary spaces, and strongly suggest an array of spatially—and perhaps temporally—distinct ritual activities (Miller et al. Reference Miller, Baiarsaikhan, Egiimaa, Konovalov and Logan2009).

Stone-line structures

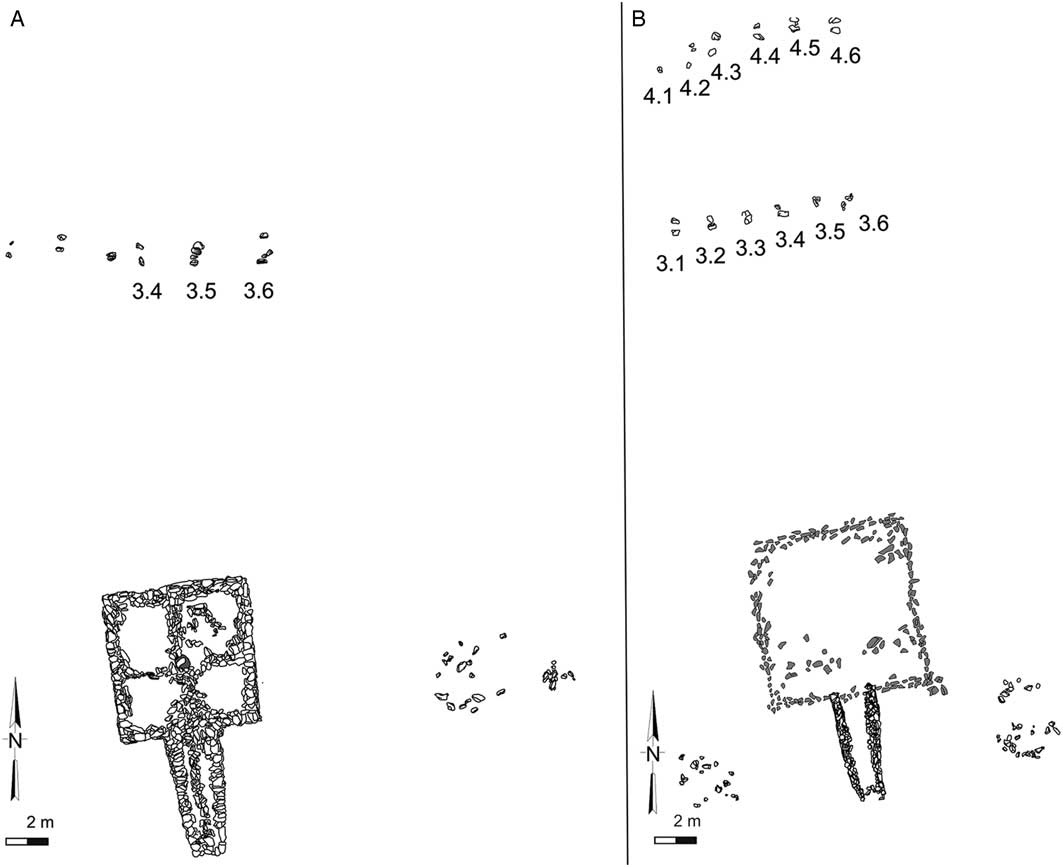

Mortuary arenas and their associated interments have long served as the primary point of entry for the study of Xiongnu society, and much of this research has focused on grave pits and their contents (Brosseder & Miller Reference Brosseder and Miller2011; Honeychurch Reference Honeychurch2015). Several decades ago, however, archaeologists in Transbaikal pushed investigations beyond the central burials to include areas in the immediate vicinity, discovering patterns of smaller satellite graves that served as accompanying burials (Konovalov Reference Konovalov1976). This approach has since been implemented by projects at similar cemeteries (Minyaev & Sakharovskaya Reference Minyaev and Sakharovskaya2002; Miller et al. Reference Miller, Baiarsaikhan, Egiimaa, Konovalov and Logan2009). More recent systematic studies have expanded this method to survey entire Xiongnu cemeteries, and have drawn attention to relatively small east–west lines of paired stones located to the north of some of the larger burials—at both ring-grave and square-tomb cemeteries (Allard et al. Reference Allard, Erdenebaatar, Batbold and Miller2002; Miller et al. Reference Miller, Baiarsaikhan, Egiimaa, Konovalov and Logan2009; Bayarsaikhan et al. Reference Bayarsaikhan, Egiimaa, Miller, Konovalov, Johannesson, Machicek, Logan and Neily2011; Yerööl-Erdene Reference Yerööl-Erdene2014; Yerööl-Erdene et al. Reference Yerööl-Erdene, Gantulga, Bemmann, Brosseder, McGlynn and Reichert2015; Eregzen et al. Reference Eregzen, Erdenesuvd, Batdalai, Mandakh and Enkhbold2017; Figure 1). These lines of stone pairs are set relatively close to, and are more or less centred on, the surface structures of the graves that they accompany. In the case of square tombs, stone lines lie parallel to the northern walls of the mounds and echo schemes of additional lines that cross-cut the tombs (Figure 3A). They also appear to complement the ramped entrances added to the southern walls of the tomb mounds and the small graves flanking the east or west sides of the tombs (Figures 2–3; see also Miller et al. Reference Miller, Allard, Erdenebaatar and Lee2006).

Dated bone samples from several stone pairs at THL indicate a relative contemporaneity of stone lines with Xiongnu burials. Samples from stone line THL-82 (Figure 4), for example, span between 1885 and 1925±30 cal BP (Table 1). This corresponds to the 2013–1946 cal BP date for tomb THL-64 (Brosseder et al. Reference Brosseder, Bayarsaikhan, Miller and Odbaatar2011), and the relatively narrow timeframe for Xiongnu square tombs (radiocarbon dated to the late first BC to first century AD) (Brosseder Reference Brosseder2009). Radiocarbon dating of faunal samples from SBR-16 (2051–1982 cal BP) exhibit an equivalent time span consistent with the late Xiongnu-era date for this cemetery (Brosseder et al. Reference Brosseder, Bayarsaikhan, Miller and Odbaatar2011). Radiocarbon dating of faunal remains from a stone line and its corresponding ring-grave burial pit at Ar-Bulan cemetery in central Mongolia (Figure 1. 7) further suggest that stone lines are contemporaneous with adjacent Xiongnu burials, rather than being later, post-Xiongnu additions. Bone samples from both contexts yielded roughly equivalent late first-century BC to first-century AD dates (Yerööl-Erdene et al. Reference Yerööl-Erdene, Gantulga, Bemmann, Brosseder, McGlynn and Reichert2015).

Figure 4 Ash and calcined bone deposits between stones of THL-82-3.1 (Khovd Archaeology Project).

Table 1 Radiocarbon dates for stone-line bone samples of THL-82. Dates calibrated using OxCal v4.2.3 (Bronk Ramsey Reference Bronk Ramsey2009) and IntCal13 atmospheric curve (Reimer et al. Reference Reimer, Bard, Bayliss, Beck, Blackwell, Bronk Ramsey, Grootes, Guilderson, Haflidason, Hajdas, Hatt, Heaton, Hoffmann, Hogg, Hughen, Kaiser, Kromer, Manning, Niu, Reimer, Richards, Scott, Southon, Staff, Turney and van der Plicht2013).

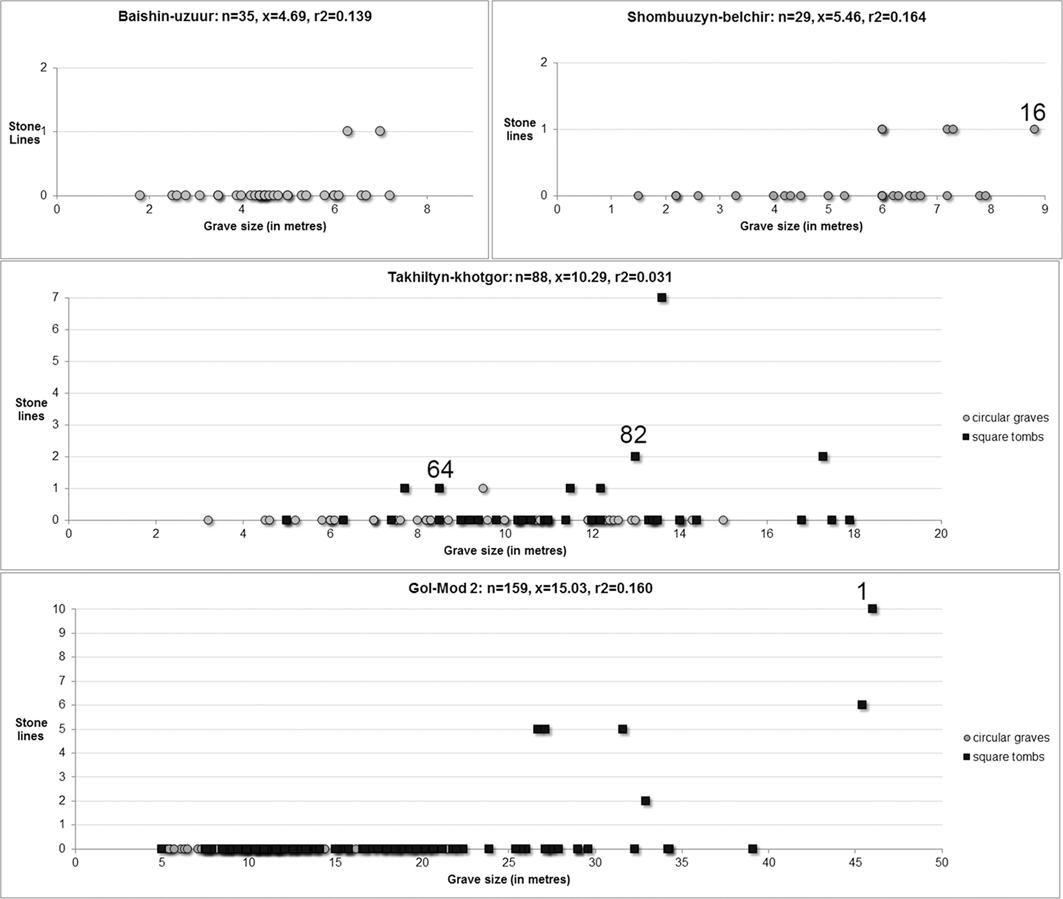

The few Xiongnu cemeteries surveyed where attention was paid to smaller features display a general pattern, in which stone lines (as well as satellite graves) tend to accompany the larger-sized grave structures of each burial ground (Figure 5). Only a small proportion of graves at each cemetery, however, are associated with stone lines, and not all of the largest graves have them. At Gol Mod 2—the largest-known Xiongnu cemetery—stone lines were definitively identified in association with only six of the 98 square tombs, and only for those graves well above the mean size distribution (i.e. >25m wide). Despite an ostensible trend for larger graves to have associated stone lines, there is no categorical correspondence between the size of grave stone structures and the number, or even presence, of stone lines. This patterning suggests the use of stone lines not merely for the largest tombs and cemeteries of the Xiongnu realms, but rather for the burials of prominent individuals (i.e. those with larger grave structures and more abundant grave furnishings) within numerous cemeteries of varying scales. Stone lines and their associated ceremonies may have represented practices that were drawn upon to venerate further, or enhance the eminence of, a deceased individual within a certain community.

Figure 5 Size of Xiongnu grave markers (metres) vs number of stone lines per grave. The numbers of specific graves are given (graph by B. Miller).

Stone-line deposits

Archaeological investigations of stone lines located north of two fully excavated square tomb complexes (THL-64 and THL-82) have revealed heavily calcined and fragmented (<10mm in size) faunal remains. These were mixed within an ashy matrix containing charcoal fragments that were collectively deposited between the stones of many individual stone pairs (Figures 3–4; Bayarsaikhan & Miller Reference Bayarsaikhan and Miller2008). That no other cultural deposits were identified between the pairs of stones or around the stone lines strongly suggests that the deposits of burnt material were reserved for the spaces between sets of paired stones. Subsequent excavations of stone lines at other Xiongnu cemeteries in central Mongolia have revealed similar patterns of deposition. The 10 stone lines north of the largest square tomb at Gol Mod 2 (Figure 2D), for example, yielded burnt bone and ash deposits between many of the stone pairs (Erdenebaatar et al. Reference Erdenebaatar, Iderkhangai, Mijiddorj, Orgilbayar, Batbold, Galbadrakh and Maratkhaan2015: 211). Ash and burnt bone fragments were also recovered from between stone pairs in a line located north of the ring grave at Ar-Bulan (Yerööl-Erdene et al. Reference Yerööl-Erdene, Gantulga, Bemmann, Brosseder, McGlynn and Reichert2015). The bone fragments recovered from the deposits at Gol Mod 2 and Ar-Bulan, however, have yet to be analysed.

The majority of bone specimens recovered from THL and SBR were identified as belonging to either medium- (e.g. sheep, goat or small deer) or large- (e.g. cattle, yak, horse or large deer) sized mammals, with the former group most frequently represented at both SBR and THL. Bone fragments belonging to Ovis/Capra sp. and Bos sp. were consistently found at both sites, although the relative abundance of bone specimens attributed to medium- and large-sized mammals varies between deposits. Only one stone pair (4.6 of THL-82), for example, yielded bone fragments primarily belonging to large mammals (Figures 5–7).

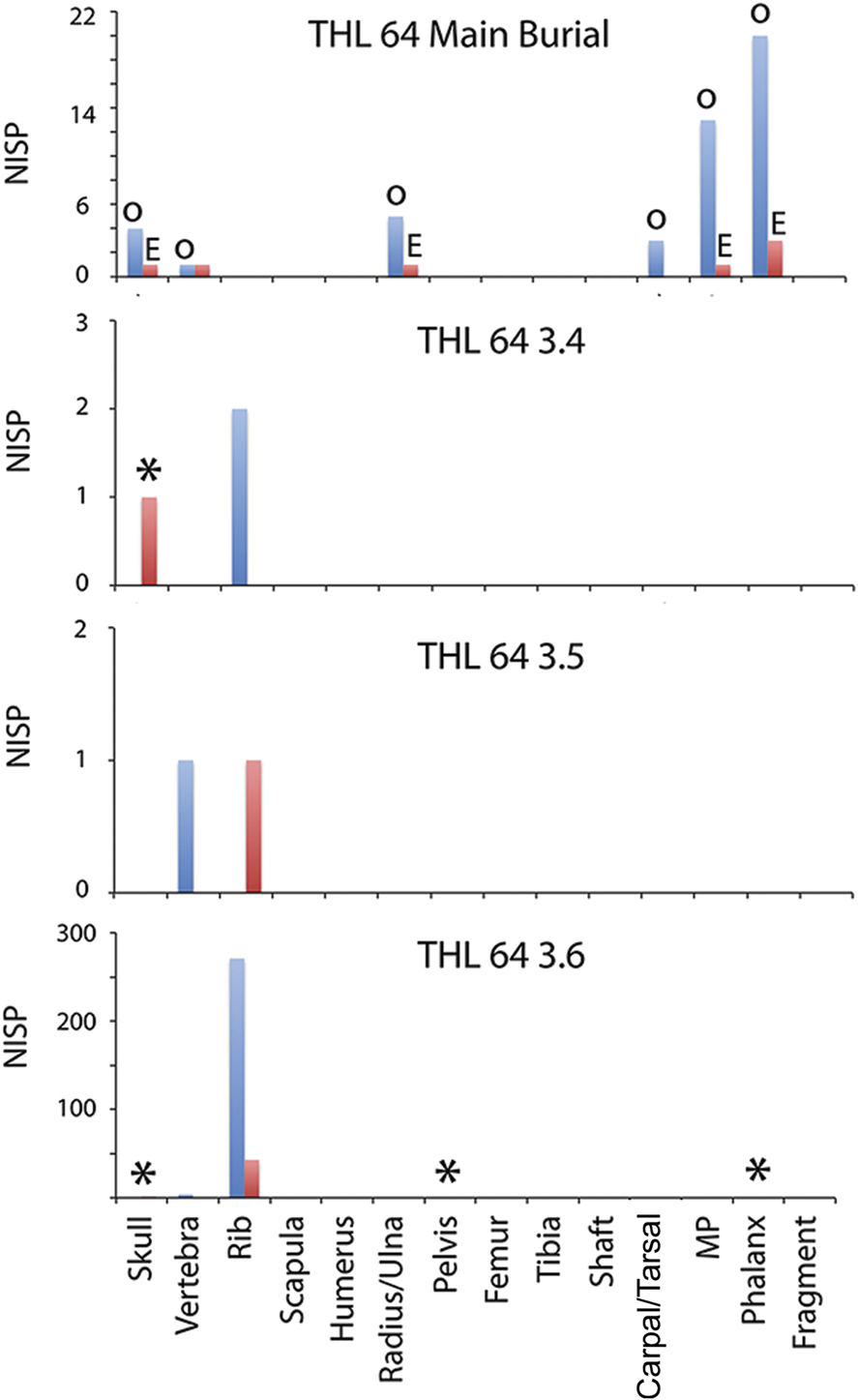

Figure 6 THL-64 distribution of skeletal elements identified as belonging to medium mammals (red bars) and large mammals (blue bars);‘main burial’ includes skeletal elements in THL-64 burial pit, o=Ovis sp.; E=Equus sp.; THL-64-3.4 asterisk indicates Bos sp.; THL-64-3.6 asterisks indicate Ovis/Capra fragments (skull n=1; pelvis n=1; Ph1 n=1) (figure by C. Makarewicz and B. Miller).

Figure 7 THL-82 distribution of skeletal elements identified as belonging to medium mammals (red bars) and large mammals (blue bars); all asterisks indicate Ovis/Capra fragments: A) THL-82-3.3 skull fragments (n=13); THL-82-3.5 skull fragments (n=4); B) THL-82-4.6 skull fragment (n=1) (figure by C. Makarewicz and B. Miller).

Despite high fragmentation, many bone specimens recovered from stone-line deposits were attributable to specific skeletal elements. Rib fragments are the most abundant skeletal part represented at THL, while long bone shafts were most frequent at SBR; cranial fragments and the most distal extremities (e.g. phalanges) were relatively rare at both sites. There are also differences in the total number of identified specimens recovered from each stone pair deposit. While approximately 200–300 bone fragments were found between each pair in the SBR-16 line, deposits from stone pairs in lines north of the THL-64 and THL-82 square tombs yielded a broader range between one and approximately 750 fragments. All bone fragments were burned, with approximately 30 per cent of fragments being fully calcined. This indicates prolonged exposure to fire.

Of the three stone pairs north of THL-64 that contained deposits, the taxonomic and skeletal element composition—as well as the quantity of faunal remains—varied somewhat (Figure 6). The duration of burning is influenced by the amount of bone placed in the fire (Costa Reference Costa2015); the stone-line deposits containing few bone fragments may have fuelled shorter-lived fires. At THL-64, stone pair 3.4 yielded remains comprising a few medium mammal rib fragments and a cattle tooth fragment, while pair 3.5 yielded a small quantity of medium and large mammal rib and vertebral bone fragments. In contrast, pair 3.6 yielded a considerable quantity of medium and large mammal rib fragments, as well as some sheep/goat cranial, pelvic and metapodial fragments. Pair 3.4 yielded few bone fragments in a thin ash deposit, whereas the few fragments from pair 3.5 were in a dense (50mm thick) and broad (1.1m wide) ash deposit. Pair 3.6, however, contained over 300 bone fragments within a 0.95m-wide by 30mm-thick ash deposit.

The faunal remains deposited between the two lines north of THL-82 were also highly fragmented, calcined and variable in composition (Figure 7). All stone pairs of the first line (3.1–3.6) yielded ashy deposits containing faunal remains, although the pairs appear to alternate between dense ash deposits containing several hundred bone fragments and sparse ash deposits containing fewer than 100 bone fragments. Most stone pairs of the second line (4.1–4.6), however, contained only sparse ash deposits containing fewer than a hundred bone fragments. Pair 4.6 yielded more than 100 bone fragments, over half of which belonged to a large mammal, while 4.4 contained no bones.

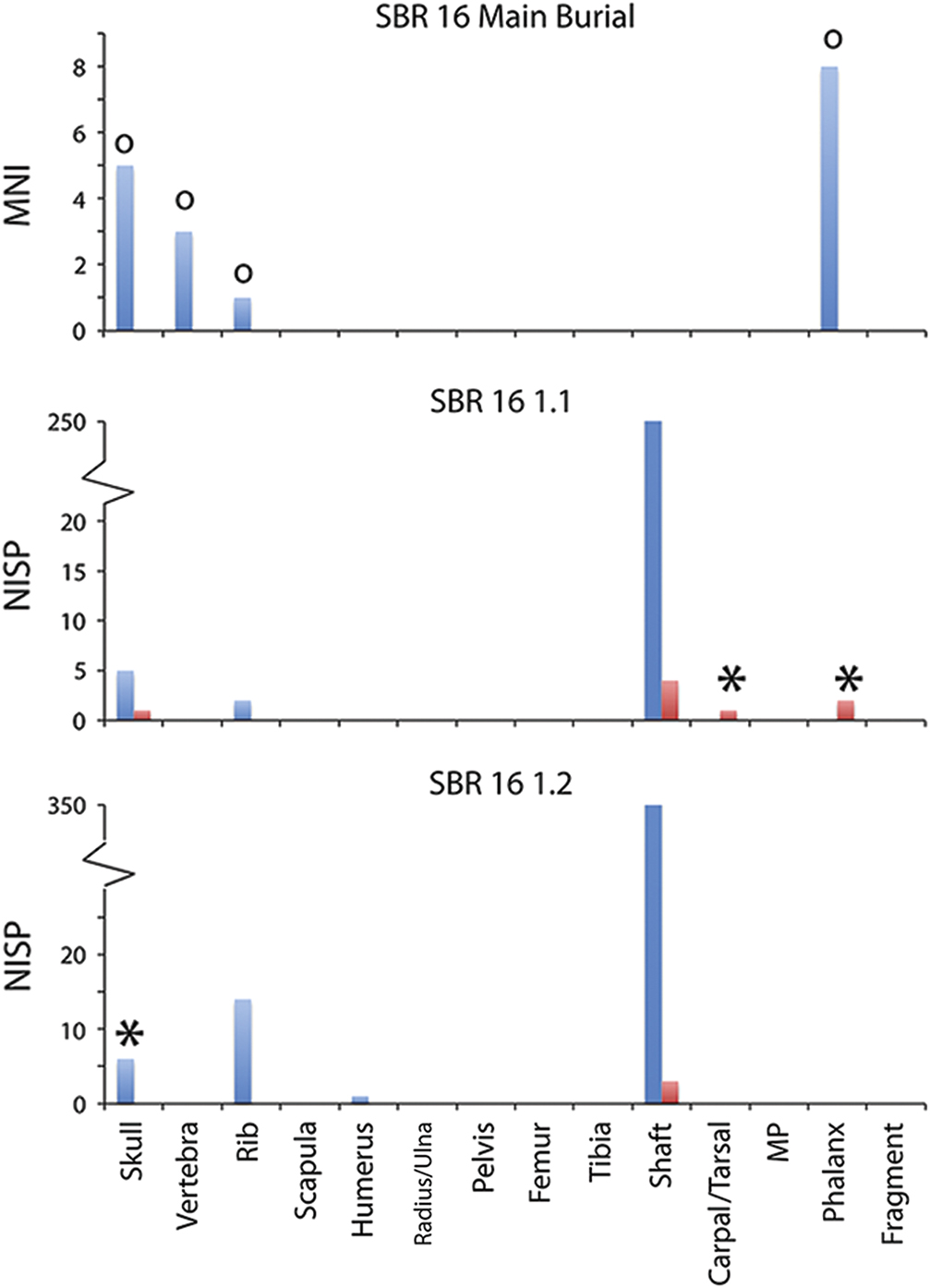

At SBR, sparse ash deposits containing around 20 bone fragments were also identified in the stone line located north of one of the largest ring graves at SBR, number 16 (Figure 8). As with the THL-64 stone line, ash deposits were evident between only some of the stone pairs (1.1–1.2), with four of the six pairs devoid of such deposits. The majority of calcined bone fragments recovered from stone pairs 1.1 and 1.2 are from medium mammal long bone shaft fragments, with some cranial and rib fragments also present.

Figure 8 SBR-16 distribution of skeletal elements identified as belonging to medium mammals (red bars) and large mammals (blue bars). ‘Main burial’ includes skeletal elements in SBR-16 burial pit, o=Ovis sp.; SBR-16-1.1 asterisk indicates Bos sp. (Talus n=1; Ph2 n=2); SBR-16-1.2 asterisk indicates Ovis/Capra molar fragments (n=4) (figure by C. Makarewicz and B. Miller).

Fat within bones is a good fuel source and provides energy for extended combustion times. The high frequency of calcined bones (around 30 per cent), high fragmentation rates (around 85 per cent of bone fragments smaller than 10mm in size for most deposits), and prevalence of shaft/rib fragments (approximately 95 per cent) exhibiting transverse and right-angle fracture patterns, are all consistent with fragmentation caused by thermal alteration (Théry-Perisot et al. Reference Théry-Parisot, Costamagno, Brugal, Fosse and Guilbert2005; Costa Reference Costa2015). Along with a high abundance of spongy bone (e.g. the centrum of the vertebra) observed in some deposits (e.g. n=51 for THL-82-3.5; Figure 7), the collective characteristics of bone fragments in stone-line deposits at SBR and THL are strongly consistent with the use of animal bone as fuel (Mentzer Reference Mentzer2009). Wood is required to start bone fires (Costamagno et al. Reference Costamagno, Théry-Parisot, Brugal and Guibert2005; Théry-Perisot et al. Reference Théry-Parisot, Costamagno, Brugal, Fosse and Guilbert2005; Yravedra & Uzquiano Reference Yravedra and Uzquiano2013); fires fuelled by a combination of both bone and wood burn significantly longer and require less re-fuelling than wood-only fires (Théry-Perisot Reference Théry-Parisot2002). The presence of both charcoal and bone fragments in the stone-line ash deposits may indicate that small wood fires were placed between stone lines, ignited and bones were then added to the fire, although there is no evidence of scorching or heat change on the stones. Spongy proximal epiphyses and axial skeletal parts contain high amounts of fat, and thus provide a long, slow burn while shaft portions burn faster due to their lower fat content (Théry-Perisot et al. Reference Théry-Parisot, Costamagno, Brugal, Fosse and Guilbert2005). Consequently, the addition of spongy elements extends flame duration better than other skeletal parts (Yravedra et al. Reference Yravedra, Baena, Arrizabalaga and Iriarte2005; Yravedra & Uzquiano Reference Yravedra and Uzquiano2013). The under-representation of spongy bone relative to dense cortical bone in stone-line ash deposits probably reflects its vulnerability to post-depositional taphonomic processes. These select against less dense trabecular bone (e.g. Lyman Reference Lyman1994), which is probably further susceptible to loss from the archaeological record following calcination.

While most shaft fragments recovered from all deposits at SBR and THL exhibit fragmentation caused by thermal alteration, there is a consistent presence of fragments, from both medium and large mammals, that exhibit an acute/obtuse fracture angle, a helical fracture outline and a smooth fracture surface consistent with the breakage of fresh bone (Outram Reference Outram2001). Although intensive processing of carcasses for marrow extraction may have occurred as part of Xiongnu food-focused ceremonies, the presence of fresh breakage fractures could also reflect the intentional dismantling of bones to increase the energy availability provided by fat. Although this processing would decrease fire duration somewhat, it would effectively increase fire intensity (Costa Reference Costa2015). Notably, bone-fuelled fires, while providing long-lasting flames, are generally low energy and not suitable for cooking (Théry-Perisot et al. Reference Théry-Parisot, Costamagno, Brugal, Fosse and Guilbert2005); this strongly suggests that fires lit in between stone lines served other—perhaps sacred or ceremonial—purposes.

The species of livestock and their skeletal parts placed in stone-line deposits appear to diverge from those placed within the graves of the deceased at THL and SBR. Sheep/goats are present in both grave pits and stone lines; horses are restricted to grave deposits, and cattle appear only in the stone lines. Graves contain mostly skulls and extremities, whereas stone-line deposits more frequently yielded rib and shaft fragments. The skulls and extremities placed within the grave pits represent body portions of lower food value, and it may be that other elements bearing higher meat and fat yields were consumed by funerary participants. Thus, heads and other low-utility portions could have served as visible, quantifiable reminders of the livestock wealth sacrificed during the funerary ceremonies (Makarewicz Reference Makarewicz2010).

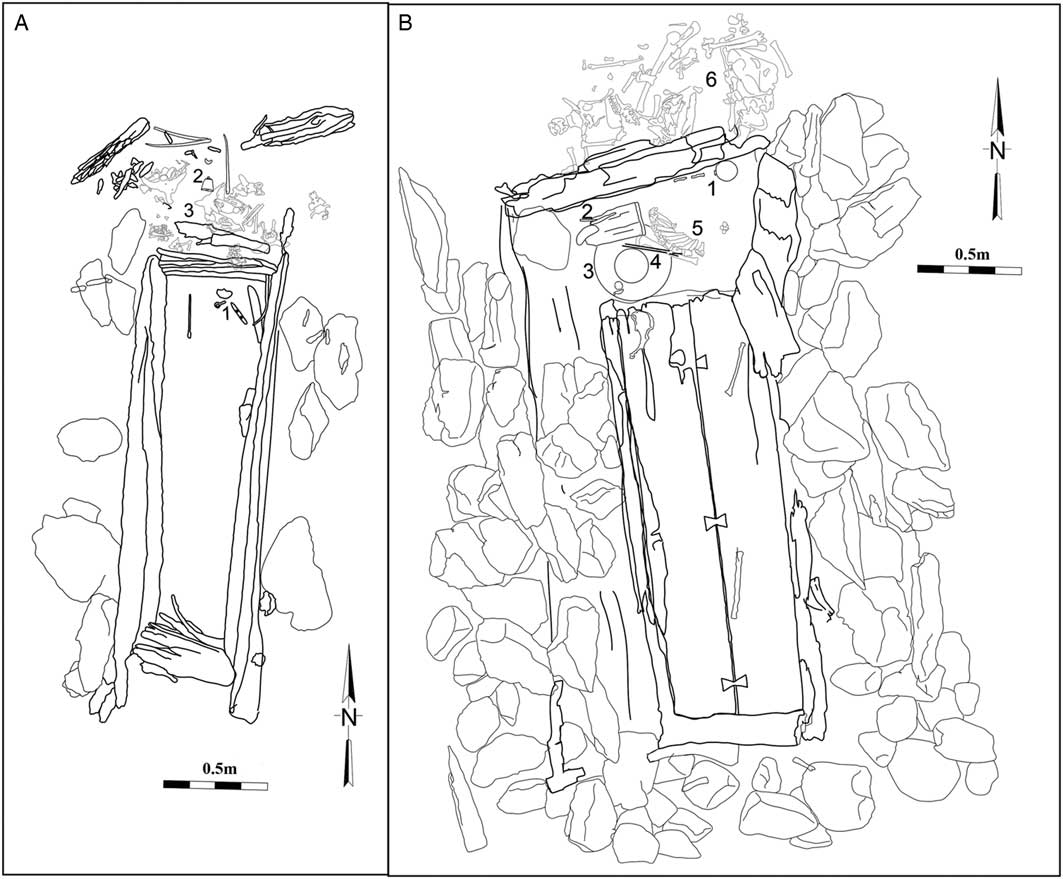

For SBR-16, the prevalence in the stone line of shaft fragments, and only some cranial and rib pieces representing mostly sheep/goat (Figure 8), contrasts with the skulls, phalanges and caudal vertebrae of four sheep placed just north of the coffin (Bayarsaikhan et al. Reference Bayarsaikhan, Egiimaa, Miller, Konovalov, Johannesson, Machicek, Logan and Neily2011; Figure 9A.3). THL-82 shows a similar pattern, with the skulls, metapodials and phalanges of five horses placed just north of the tomb chamber (Navaan Reference Navaan1999). The stone lines, however, contained primarily medium mammal rib fragments plus a few large mammal fragments (Figure 7). Rib and some vertebral fragments dominate the faunal assemblage in the THL-64 stone line, but shaft fragments are poorly represented (Figure 6). The faunal remains placed just outside the tomb chamber, however, contain the complete skulls of three sheep, articulated with axis and atlas vertebrae, as well as the lower forelimbs (radius, metacarpal, phalanges), hind limbs (metatarsals, phalanges) and caudal vertebrae (Miller et al. Reference Miller, Baiarsaikhan, Egiimaa, Konovalov and Logan2009; Figure 9B.3). A complete horse skull and radius, with the articulated first, second and third phalanges, were also placed with the sheep remains.

Figure 9 A) Shombuuzyn-belchir 16: 1) bone horse-bridle cheek-piece; 2) bronze horse-bell; 3) sheep/goat skulls, sacrae and phalanges (after Bayarsaikhan et al. Reference Bayarsaikhan, Egiimaa, Miller, Konovalov, Johannesson, Machicek, Logan and Neily2011); B) Takhiltyn-khotgor 64: 1) iron ladle; 2) painted wooden tray; 3) storage jar; 4) bone chopsticks; 5) sheep/goat shank and vertebrae; 6) horse and sheep/goat skulls, cervical vertebrae, sacrae and phalanges (after Miller et al. Reference Miller, Baiarsaikhan, Egiimaa, Konovalov and Logan2009).

An additional deposit was placed within the wooden chamber of THL-64, comprising one unfused tibia and 10 articulated thoracic vertebrae of a caprine. This contrasts with the taxa represented in both the stone-line and burial-pit deposits, as well as the treatment of bone remains, and may indicate that these skeletal parts were intended for consumption. They were set in the northern chamber section with a painted wooden tray, an iron ladle and a large food storage jar, and a pair of bone chopsticks were lain beside the articulated portions (Miller et al. Reference Miller, Baiarsaikhan, Egiimaa, Konovalov and Logan2009: 306). Similarly, seven sheep/goat thoracic vertebrae were placed in a bronze cauldron beside the coffin of SBR-7, alongside a wooden ladle (Bayarsaikhan et al. Reference Bayarsaikhan, Egiimaa, Miller, Konovalov, Johannesson, Machicek, Logan and Neily2011: 143–44). Vertebrae, ribs and limb bones were placed in ceramic cooking pots and metal cauldrons within Xiongnu graves across Inner Asia (e.g. Sh.U.A. et al. 2011; Ligneraux Reference Ligneraux2015). These remains strongly suggest the use of such animal parts for consumption—by spirits, ancestors or the dead in the afterlife—and may aid in explaining the presence of fragments of many of these same elements in stone-line ash deposits, echoing the consumption of analogous portions by ritual participants.

Animal sacrifices and the politics of rituals

The discrete placement, and distinct contents, of stone-line deposits demonstrate a greater complexity in the array of Xiongnu mortuary practices than previously thought. Careful consideration of the full spectrum of faunal remains present at these cemeteries reveals evidence for multiple ritual activities—and perhaps distinct ceremonial events—carried out in association with Xiongnu burials. A wide array of rituals conducted with offerings to ancestors, spirits and the heavens are intimated in records about the Xiongnu (Sima Qian Reference Sima1959: 2892); and sheep and cattle are specifically mentioned as animals sacrificed by ritual practitioners for inflicting curses (Ban Gu 1962: 3913). Regardless, however, of specific religious beliefs or connotations of the rituals through which faunal remains in mortuary arenas were processed, it is the mechanics and the social motivations for these sacrifices and offerings of livestock that pertain most to the political dynamics at play in these mortuary arenas.

Animal remains placed in Xiongnu grave pits probably embodied offerings presented to, or on behalf of, the deceased. These included fleshy portions placed with(in) feasting accoutrements and destined for consumption (possibly by the dead themselves), but most often comprised extremities representative of whole, sacrificed livestock. Funerary rites would have included competitive demonstrations of material and social capital via animals sacrificed from the herds of the deceased or of those participating in the funerary ceremonies (Miller Reference Miller2009: 358; Makarewicz Reference Makarewicz2017: 415). Animal remains in the stone lines may have provided fuel for ritual fires, been immolated as ritual offerings or were the result of a combination of such activities. The abundance of shaft and rib fragments representing parts with high food values (portions not present among the animal extremities deposits within graves) suggests that stone-line deposits may also be the remains of feasting—even if the low volume of ash and quantities of bone fragments in stone-line deposits do not reflect the entire discard of feasting events. The taxonomic discord at THL and SBR between species placed in grave pits (sheep, goats and horses) and those in stone lines (mostly sheep/goat and some cattle) also suggests that separate animal assemblages were accessed for the ritual practices associated with the burnt stone-line deposits. Although the complete process of stone-line rituals is difficult to determine, the mechanics evident in taxa, portions, treatments and placements of animal remains diverge considerably from those in grave pits. The corresponding differences in selection, apportion and consumption of sacrificed animals demonstrate qualitatively different rituals for venerating the deceased that were distinct from funerary interment rites.

The spatial separation of stone lines from grave pits further differentiates the rituals that produced the heavily burnt and fragmented bones from the funerary practices that deposited selected animal portions. Features external to the grave pit and its surface structure, such as the stone lines, would have enabled post-interment ritual activities—whether moments or years after the closing of the grave. This intimates the extended use of cemeteries, not only through the addition of interments to collective burial sites, but also through the addition of commemorative rituals for individual burials. Just as spatial divergence in offering depositions within graves may reflect the different functions of their associated rites (Flad Reference Flad2002), additional divisions via features outside of the grave pit may extend the temporality of mortuary practices and individual graves. Such reinforcement of the memory, and its social currency, of a particular person would certainly have played a significant role in power dynamics among Xiongnu elites—even by altering the memory and status of a deceased person. A grave with minimal funerary offerings could subsequently be augmented by animal offerings, the remains of which were placed in the stone lines flanking the grave. Conversely, an individual with ample funerary offerings may not have been followed by later animal sacrifices on their behalf. The differences between graves SBR-16 (9m surface ring, 4 caprine skulls in pit, 1 stone line) and SBR-8 (7.5m surface ring, 15 caprine skulls in pit, no stone line) exemplify the wide variance between investments in funerary rites and in subsequent offerings. As those who had already been buried and commemorated were further venerated, so would supplementary rituals bolster the prominence of those persons closely associated with the deceased.

Only a few Xiongnu cemetery surveys have so far focused on documenting less visible features, such as stone lines, and analyses of the faunal remains deposited in Xiongnu stone lines are unique to the current study. Nevertheless, the stone lines and their associated deposits provide valuable evidence for distinct ritual activities that were conducted either contemporaneously with, or, quite possibly, subsequent to funerary interment rites. They prompt us to consider a suite of ceremonial elaborations at Xiongnu graves before, during and after the action of burying the dead that served to reify crucial social connections and bolster competitive claims among steppe pastoral elites. Power was demonstrated through the expenditure of labour, in the construction of burial markers and chambers, and in the expenditure of valuable livestock, the primary livelihood of pastoral societies. These ritualised animal offerings expand our discussions of mortuary arenas beyond examinations of conspicuous constructions (e.g. Conolly Reference Conolly2017), and into the full spectrum of conspicuous actions. These include significant ‘costly’ sacrifices from herds of households represented in the archaeological record by the skulls and extremities placed within the Xiongnu graves; only through more intensive studies of the minute calcined bone fragments set between accompanying stone pairs in Xiongnu cemeteries can we address the exact nature and degree of ‘cost’ related to these animal offerings. Burial structures and spaces in Xiongnu mortuary arenas held the potential to be transformed through the addition of visible features and subsequent rituals of repeated deference. Single-event burials became recurring monuments, and burial grounds became more complex arenas and foci of social politics.

Acknowledgements

The American Center for Mongolian Studies funded the initial Khovd surveys. Excavations were funded by the Silk Road Foundation and a dissertation grant from the American Council of Learned Societies & Henry Luce Foundation. THL bone samples were dated at Poznań Radiocarbon Laboratory through the ERC Consolidator Grant ‘Nomadic Empires’ (615040). The authors are grateful to the 2007 and 2008 Khovd Project field crews for their diligent excavation of the stone lines, and to Julia Clark, James Williams and Joshua Wright for help in analysing the bones.