Introduction

The Cherokee are one of the storied indigenous Native American peoples of North America. At the time of European contact, the Iroquoian-speaking Cherokee subsisted by farming and hunting a homeland that straddled the Appalachian Mountains, encompassing parts of the modern U.S. states of Georgia, South Carolina, North Carolina and Tennessee. White incursions and subsequent conflict with the intruders during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries initiated what would become a massive displacement of Cherokees to the west: the ‘Trail of Tears’. Before their total removal in the 1830s, Cherokee people interacted socially and economically with their white neighbours, adopting some of the newcomers’ practices. These interactions, however, were nearly always one-sided, preferentially benefiting the immigrants. Regardless, Cherokee culture and intellectual life were vibrant from the time of contact through to, and after, the displacement to the west; they remain so today.

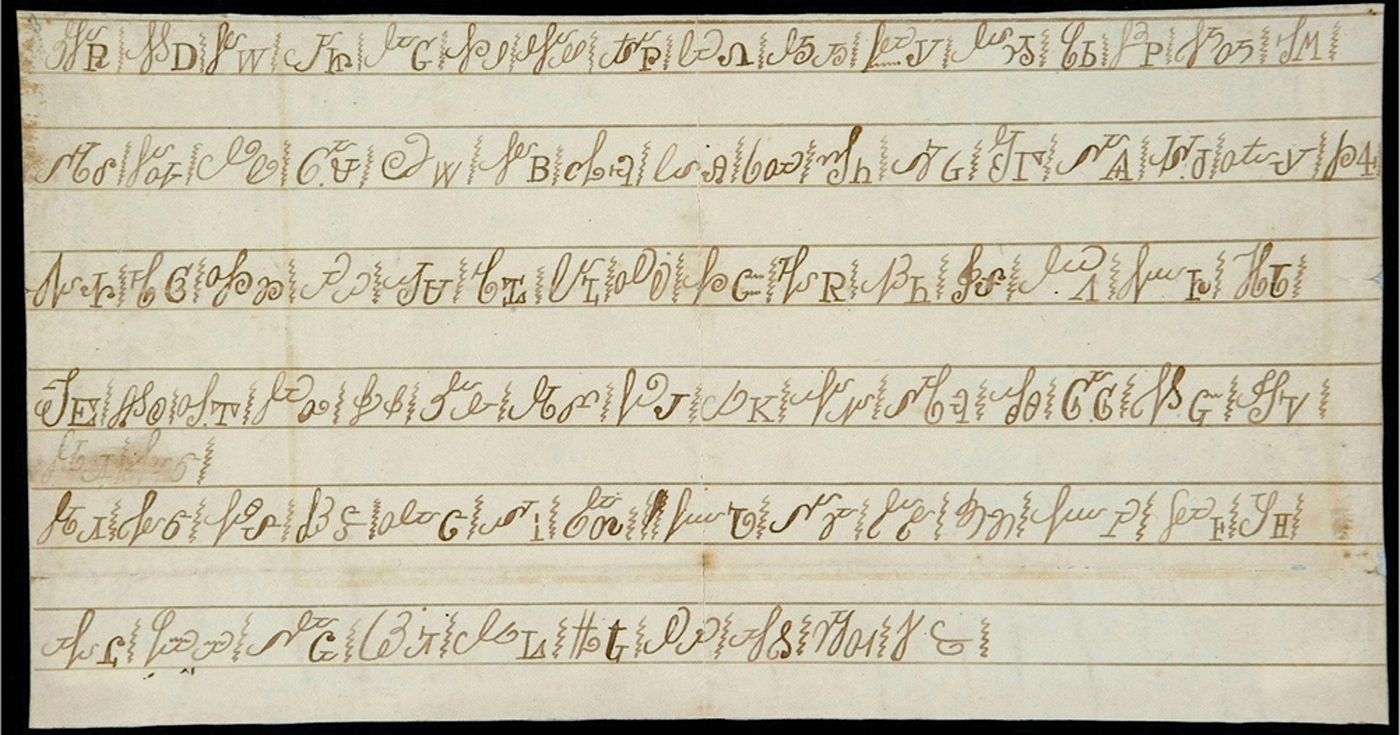

In the early nineteenth century, a great Cherokee scholar named Sequoyah invented a syllabary system that allowed his people to communicate in their own language through writing. Although little is known about how the syllabary originated, it was adopted formally as the official Cherokee writing system in 1825. This remarkable invention occurred in and around a Cherokee community called Willstown—modern Fort Payne, Alabama—where Sequoyah resided from sometime around the turn of the nineteenth century until c. 1826 (McKenny & Hall Reference McKenney and Hall1848). The tribe adopted the syllabary after Sequoyah and his daughter demonstrated its efficacy by using it to communicate while out of eyesight and earshot (Payne & Butrick Reference Payne and Butrick2010). Almost immediately, the syllabary went into wide use among the Cherokee people.

In Willstown, there were a number of caves, including one known today as ‘Manitou Cave’. We do not know what the Cherokees of Willstown called this cave, but ‘Manitou’ is not a Cherokee term; this name was probably assigned in the late nineteenth century by whites, in an attempt to enhance its interest to tourists. Manitou Cave has long been renowned by Euro-American tourists for its beautiful speleothems, the sizes of its passages and its impressive underground stream. But long before whites came to Willstown, Cherokees and earlier Native Americans used the cave. Until now, these indigenous uses have remained unrecorded, as subsequent Historic-period alterations in the cave removed most typical archaeological evidence, such as artefacts and stratified cultural deposits. Still, the Cherokee and their antecedents considered caves to be powerful places: places where water emerged from the lower world, where the spiritual and visible worlds were close, and where the living could seek spiritual strength in seclusion (e.g. Mooney Reference Mooney1900). These ancient indigenous perspectives—typically inferred through archaeological evidence—are instead materialised in Manitou Cave by Cherokee syllabary inscriptions on the walls. These writings record first-person accounts of how nineteenth-century Cherokees used and viewed the cave context. This article presents these new discoveries for the first time. We also present an indigenous archaeology of the cave, representing a collaborative research effort between Cherokee and Euro-American scholars. While our results confirm some of the general interpretations previously proposed for ancient Native American cave use in the American Southeast, they also develop a richer and more textured understanding of Manitou Cave. This has been possible only through engagement by Cherokee scholars who can read and give meaning to the inscriptions and their context.

The Cave and its history

Manitou Cave comprises a cavern, running north-west to south-east, formed in Mississippian-age Bangor Limestone. First mapped in 2009, the cave is 1.67km long, with a total vertical extent of 17m. Approximately 1.5km from the cave's mouth, a subterranean stream emerges into the main passage and flows outward, meandering along the passageway. The passage itself is wide and easily navigated, although the stream must be crossed in several places. By 1888, Manitou was opened to tourism, and in the early twentieth century, the cave entrance and interior were partially excavated to facilitate visitor access; passages were levelled and widened, and bridges were built over the stream. These alterations facilitated a convenient public tour, which provided views of the cavern's many water features and flowstone formations. Unfortunately, these modifications also obliterated evidence of earlier cave use. Only the walls remain unmodified, except for signatures, drawings and graffiti made by tourists and other visitors.

Both Manitou Cave and the surrounding community have long histories. In the 1780s, after siding with the British during the American War of Independence, some Cherokee people moved west from their ancestral homeland in the Appalachian Mountains and took refuge in modern-day Alabama to avoid reprisals from the new U.S. government (Hoig Reference Hoig1995: 20–30; McLoughlin Reference McLoughlin1995; Perdue & Green Reference Perdue and Green2007). The resulting Cherokee refugee settlements were called ‘Chickamauga Towns’ or ‘Lower Towns.’ One such community, Willstown, developed around Manitou Cave. At its origin, Willstown was at war with the United States. By 1801, however, after Chickamauga military resistance ended, U.S. Indian Agent Return J. Meigs reported to the Secretary of War that the community had become “the most important town in the Cherokee Nation” (McLoughlin Reference McLoughlin1995: 60).

The population of Willstown grew as treaty land cessions displaced more Cherokee people from their homelands to the east. Not all refugees had the same view of Cherokee-U.S. relations, however. Heated debates arose between those who wanted to avoid political and social interaction with whites, and those who believed that appeasement and assimilation were the only ways to survive (Mooney Reference Mooney1900; Perdue & Green Reference Perdue and Green2007: 91–115). The issue of Cherokee land rights culminated in 1830 when U.S. President Andrew Jackson signed the Indian Removal Act, which mandated ethnic cleansing of Native People from east of the Mississippi River. The U.S. Army established the Fort Payne garrison at Willstown to concentrate local Cherokees forcibly, before moving them west towards their newly designated ‘homes’ in modern-day Oklahoma. Cherokee removals on the ‘Trail of Tears’ were mostly complete by 1839 (Perdue & Green Reference Perdue and Green2007: 116–40).

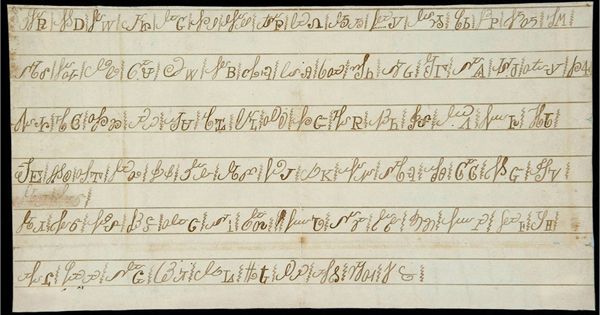

One of the most eminent residents of Willstown during the early nineteenth century was Sequoyah (Figure 1). Formally adopted by the tribe in 1825, his written syllabary system was used, among many purposes, to publish a widely read newspaper, The Cherokee Phoenix (Perdue Reference Perdue and Kwachka1994; Hoig Reference Hoig1995). Born in what is today Tennessee prior to the American War of Independence, Sequoyah moved with his mother to Willstown at the turn of the nineteenth century (McKenny & Hall Reference McKenney and Hall1848). In 1813, he joined Andrew Jackson's U.S. Army at the Chickamauga settlement of Turkeytown and fought rebelling Creek Indians at Horseshoe Bend (Mooney Reference Mooney1900). In an 1828 treaty between the U.S. and Cherokee Old Settlers from Arkansas, Sequoyah is named as George Guess. Many Cherokees had English as well as Cherokee names, and this surname was passed on to some of his children (Mooney Reference Mooney1900; Hoig Reference Hoig1995). Thus, Sequoyah lived in and around Willstown for the entire duration of the syllabary's development.

Figure 1. Cherokee syllabary, handwritten version in Sequoyah's own hand (Sequoyah's hand syllabary, ink on paper, GM 4926.488, Glicrease Museum, Tulsa, Oklahoma; reproduced with permission).

In its final form, Sequoyah's writing system comprised 85 syllables, expressing all the sounds needed to reproduce the spoken language. The syllabary was precise, accurate, elegant and, perhaps most importantly, easy to learn. Within a few months of its public introduction, the system had spread across the tribe and, by the time removal was complete, most Cherokee people were literate (Perdue Reference Perdue and Kwachka1994). As it turns out, Cherokees in Willstown wrote in syllabary on the walls of Manitou Cave.

The Cherokee inscriptions

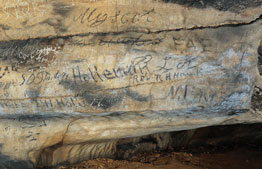

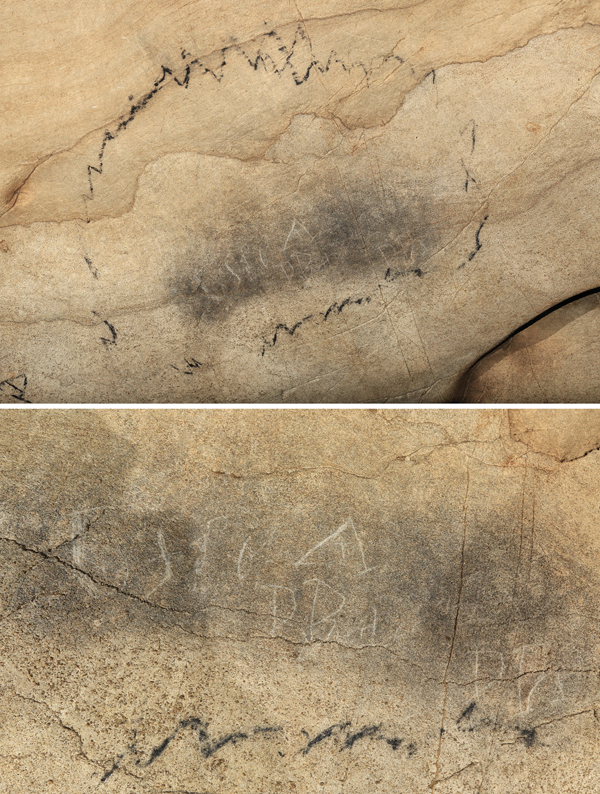

Cherokee syllabary writing on the walls of Manitou Cave was first recognised by historian Marion O. Smith and cave photographer Alan Cressler in 2006 during an examination of historical signatures on the walls. We have since identified Cherokee syllabary inscriptions in various places within the cave, although there are three main spatial groups. One group comprises individual or a few syllables written along the main passage. These isolated elements do not appear to form phrases, even when they are found in small clusters on the wall (Figure 2). The area where these individual elements occur begins approximately 120m from the cave entrance, well within the dark zone, and continues to just before the stream confluence with the main passage, 1.5km from the entrance. In the nineteeth century, river cane (Arundinaria gigantea) torches were used to light the passages, as evidenced by scrape or stoke marks on the cave walls. Single or a few syllables are difficult for even native Cherokee speakers/readers to translate and understand. This is because they may represent sounds, rather than words or phrases—elements of songs, for example, that only take their meaning from the context in which they were used. As the Cherokee syllabary encompassed regional and individualised variation related to local language dialects (Bender Reference Bender2002: 57), individual syllables can be difficult to interpret. Isolated syllabary elements are the subject of continued study, as new ones are still being discovered with ongoing examination of the cave walls. For these reasons, translation or interpretation will not be attempted here.

Figure 2. Pair of isolated Cherokee syllabary elements (average syllabary element height approximately 100mm) (photograph by A. Cressler).

Instead, we focus on two areas within the cave where Cherokee inscriptions are extensive and where their meanings can be translated. The first area is more than 1.5km into the cave's main passage, the second approximately 300m from the cave entrance. Each area contains multiple inscriptions, and one inscription in the deeper area includes a written date. Associated with these insciptions are signatures, one of which is a name that appears twice in the cave and which significantly enhances the historic importance of the site. All of the inscriptions in the two areas concern ceremonial and/or spiritual matters; they were probably made in the seclusion of the cave and were not intended for general audiences. With this in mind, we provide only limited translation of inscriptions that contain culturally sensitive material.

Inscriptions 1.5km from the cave entrance

We begin with the first set of Manitou Cave inscriptions identified in 2006 as syllabary. These are located deep in the cave—well beyond the tourist trail system—in a room 30m long by 15m wide, precisely where the underground stream emerges into the main cave passage and then flows towards the entrance. This part of the cave is remote, wet, quiet and more secluded than areas accessible from the modern walking passages. Stylistically, the inscription (Figure 3) represents an Overhill Cherokee language dialect originally spoken on the north-western side of the Appalachian Mountains, in eastern Tennessee. This was the area in which Sequoyah was born and from where he emigrated to Willstown. The inscription records an important ritual event that took place in 1828.

Figure 3. Cherokee syllabary inscription from 1.5km into Manitou Cave (average element vertical height approximately 80mm) (photograph by A. Cressler).

The first line, ![]() , reads Aniyvli, which means ‘leaders’ or ‘the ones who lead’. The second line is key to understanding this message. Tquaneetso, written as

, reads Aniyvli, which means ‘leaders’ or ‘the ones who lead’. The second line is key to understanding this message. Tquaneetso, written as ![]() , is one of several terms used for the Cherokee stickball game (Fogelson Reference Fogelson1971). The first two lines taken together identify the authors as ‘the leaders of the stickball team’. The third line begins with a date in Arabic numerals (Sequoyah did not propose new numbers for the syllabary), ‘1828’, followed by two thick vertical lines that are separated by approximately 0.3m of unmarked cave wall. The last part of the line has several components. First is

, is one of several terms used for the Cherokee stickball game (Fogelson Reference Fogelson1971). The first two lines taken together identify the authors as ‘the leaders of the stickball team’. The third line begins with a date in Arabic numerals (Sequoyah did not propose new numbers for the syllabary), ‘1828’, followed by two thick vertical lines that are separated by approximately 0.3m of unmarked cave wall. The last part of the line has several components. First is ![]() . In Cherokee, this is Guwinikalv; ‘in their month’. Next is Guwoni, written as

. In Cherokee, this is Guwinikalv; ‘in their month’. Next is Guwoni, written as ![]() , the month of April, and the number 30 with E-ga,

, the month of April, and the number 30 with E-ga, ![]() , ‘day’. Thus, we propose that the complete translation is: ‘leaders of the stickball team on the 30th day in their month April 1828’. Note that the date reference is to ‘their month of April’, referring to Euro-Americans, who use named months. This inscription has previously been partially—and inaccurately—translated (Weeks & Tankersley Reference Weeks and Tankersley2011).

, ‘day’. Thus, we propose that the complete translation is: ‘leaders of the stickball team on the 30th day in their month April 1828’. Note that the date reference is to ‘their month of April’, referring to Euro-Americans, who use named months. This inscription has previously been partially—and inaccurately—translated (Weeks & Tankersley Reference Weeks and Tankersley2011).

We believe that this panel refers to a Cherokee stickball game played on April 30, 1828. Stickball was (and continues to be today) the Cherokee version of lacrosse. Played on a large flat field, two teams use rackets to try to move a ball into a goal protected by the opposing team (Zogry Reference Zogry2010). The game itself is very physical and injuries are common. The inscription implies that the leaders of one team—probably the ceremonial leader(s) who ritually prepare teams to participate in the game (Mooney Reference Mooney1900)—commemorated their pregame activity by writing on the cave wall. Thus, this inscription records a very specific event. It is, however, more than just a memorial of the game, because, to the Cherokee, stickball was and is more than a ‘game’. The Cherokee ball game is a ceremonial event that often continues over several days (Mooney Reference Mooney1900; Zogry Reference Zogry2010). It focuses on competition between two communities or towns who, together, epitomise the spirit and power of the people and their ancestors; the game also represents the materialisation of the danger, drama and glory of war and death (Zogry Reference Zogry2010). Through the game, spiritual renewal can be achieved, both for the players and for their communities. The stickball game itself forms only one part of the ritual, albeit the most public and accessible part for spectators; even non-Indians can observe the ball game in action, both in the past and today.

There are also private aspects to the game that each team undertakes before the contest and that cannot be viewed by non-participants. These include personal preparation, prayer and meditation. Such devotions are necessary because, as with Cherokee warriors preparing for battle, ball players are in a ‘red condition’, vulnerable to bloody injury. These activities are deeply ceremonial. Team members go into seclusion as a group, led by elders who possess specialised ritual understanding. In these private contexts, ballplayers prepare themselves spiritually for the game and the promised collective renewal, cleansing their bodies and minds with water and smoke, dancing, scratching and praying (Mooney Reference Mooney1900). Such preparation is always undertaken in seclusion, in a place where the players can ‘go to water’—that is, access purifying sacred waters, such as in the deep recesses of Manitou Cave where the karst waters emerge from their subterranean courses. Intermissions during the contest allow teams to leave the grounds and go back into seclusion for more preparation. At the end of the contest, both teams—winners and losers—go one final time to water to complete the ceremonial process (Zogry Reference Zogry2010). This is the process commemorated on the wall deep in Manitou Cave.

A second inscription (Figure 4) is located a few metres from the first, in the deep area of the cave, and it supports our interpretation of the first inscription. Its production was complex. First, the bare cave wall was blackened using candles or an oil lamp. A common technique in historic times, ‘smoking’ signs onto cave walls involved holding a burning light source very near the rock to generate a soot deposit (e.g. Smith Reference Smith1985). Once the wall was prepared, text was incised into the soot with a sharp tool, thereby exposing the light limestone beneath. The second inscription again includes three lines of text, all of which are enclosed by a scalloped-edged oval also engraved into the sooted surface (Figure 4: top). The syllabary characters used in this inscription are very small, some only slightly larger than a centimetre. Both Cherokee syllabary and English letters are used in this inscription.

Figure 4. Engraved Cherokee syllabary inscription from 1.5km into Manitou Cave in the same area as Figure 3. Top) photograph of the inscription; bottom) drawing of the middle line of syllabary. Syllabary elements vary in vertical height from 10–50mm. Photograph by A. Cressler (drawing by J. Simek).

The text begins on the first line with the English word ‘Mister’ and the letters ‘RG’, which we believe represents the initials of the inscription's author. The centre line is the longest, comprising as many as 26 Cherokee syllabary symbols, and which we have divided into two sentences (Figure 4: bottom). The first part of the inscription, ![]() , we read as Di-ge-ya-ne-s-ga-wo-di-ga-ho-dv-ge-a-ya in Cherokee, which means ‘we who are those that have blood come out of their nose and mouth’. The second part of the line,

, we read as Di-ge-ya-ne-s-ga-wo-di-ga-ho-dv-ge-a-ya in Cherokee, which means ‘we who are those that have blood come out of their nose and mouth’. The second part of the line, ![]() , A-yv-s-ge-yv-gv-s, translates as ‘I am a respectable man of authority’. The last line is a signature, in English, of one ‘Richard Guess’ (Figure 5). This engraved text therefore informs us of two things. First, that the author, Mr RG or Richard Guess, is a leader; and second, the inscription references a group—probably ballplayers—whose members are wounded and bloodied in the face, that is, in a ‘red condition’.

, A-yv-s-ge-yv-gv-s, translates as ‘I am a respectable man of authority’. The last line is a signature, in English, of one ‘Richard Guess’ (Figure 5). This engraved text therefore informs us of two things. First, that the author, Mr RG or Richard Guess, is a leader; and second, the inscription references a group—probably ballplayers—whose members are wounded and bloodied in the face, that is, in a ‘red condition’.

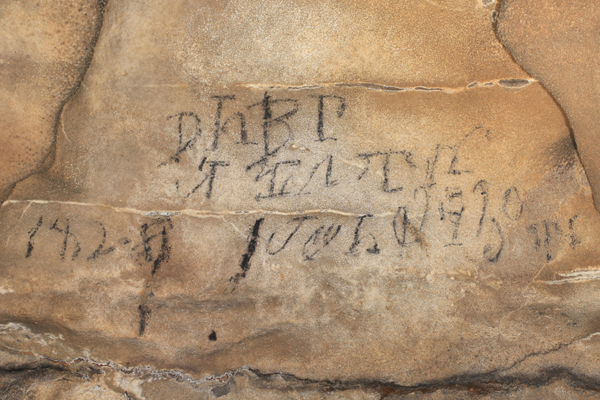

Figure 5. Signatures in English of Richard Guess. Top) engraved at the bottom of the panel shown in Figure 4; bottom) written in charcoal in a niche along the main walking passage of Manitou Cave. Note the similarity in signature hand (photographs by A. Cressler).

We interpret this inscription as referring to a Cherokee stickball game—probably the same event as recorded in the first inscription. In all the ceremonial interludes associated with these games, each team was led by a religious advisor who guided their rituals. We believe that the spiritual leader of this team was Richard Guess. As the game progressed, the condition of the team members reflected their experiences on the field, such as injuries resulting in bleeding from their noses and mouths. The same signature appears in charcoal in the cave's main walking passage, farther towards the entrance (Figure 5). Although there is no syllabary associated with the charcoal autograph, the signatures are very similar.

Who was Richard Guess? We believe that he was one of Sequoyah's sons, born to Sally, his first wife, in East Tennessee before the turn of the nineteenth century (Hoig Reference Hoig1995: 110). When still a child, Richard accompanied his parents and family to Willstown, and he was certainly with his family during the development of the syllabary. Indeed, Sequoyah's children were among the first Cherokees to learn to read and write using his syllabary (Hoig Reference Hoig1995: 40). We know that Richard lived close to Willstown and that he was contracted to help Cherokees move their belongings into concentration camps during the 1838 removal (Figure 6)—an activity that often took him through Willstown. Cherokee leaders frequently undertook this type of work to protect their people from unscrupulous white contractors, who shamelessly victimised Cherokees during the removal process (Perdue & Green Reference Perdue and Green2007). Figure 6 shows the striking similarity between the Manitou Cave signatures and the known signature of Richard Guess at the bottom of a transport voucher.

Figure 6. 11 July, 1838 Voucher for Cartage Services between the U.S. Government and Sequoyah's son Richard Guess. Note Guess's signature at bottom (U.S. National Archives and Records Administration 1838).

In summary, these inscriptions deep inside Manitou Cave reflect the use of this remote passage as a place where a Cherokee ball team went to water before and during a stickball contest in April 1828. As was (and still is) typical, they were led and guided in their preparations by a religious leader, Richard Guess, who left a written record of the event on the cave walls. Several aspects of this record are important. First, the place chosen for the private ceremonies is, in fact, very secluded—more than 1km into the cave's dark zone—far more so than usual for such events (see Zogry Reference Zogry2010). Why might this be? In the late 1820s, tensions were high among different Cherokee factions. Some favoured the accommodation of white culture, while others preferred traditional lifeways. White missionaries within the Cherokee settlements—including Willstown—were opposed to traditional religious activities, such as the stickball game, and they made their views clear in church to tribal members (Zogry Reference Zogry2010: 70). Privacy for such events may, therefore, have been even more important than usual to traditionalist practitioners. Second, the places used for private ceremonies associated with stickball were usually close to the ball playgrounds. Thus, the game itself probably occurred not far from the cave entrance. Finally, the ceremonial and exclusive nature of the activities recorded in these inscriptions suggest that caves were considered as powerful, private locales by the historic Cherokee.

Inscriptions 300m from the cave entrance

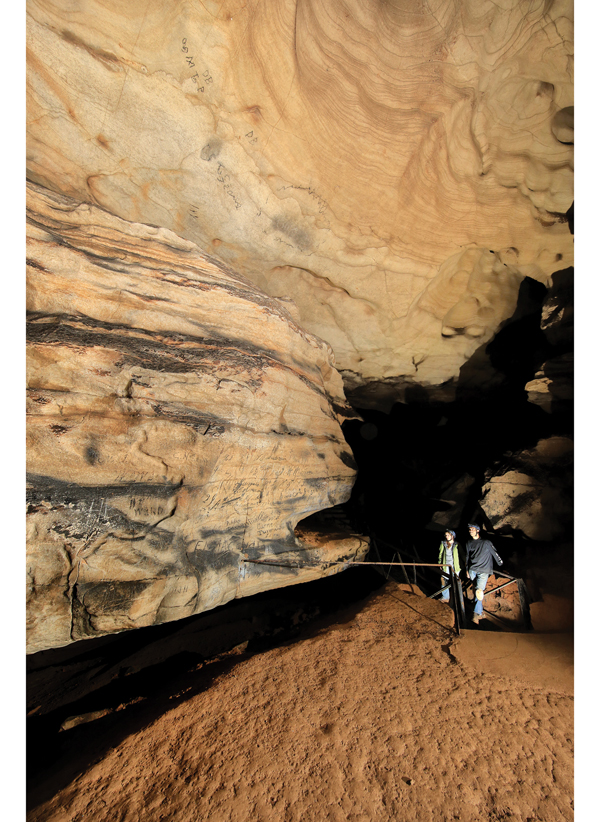

The second set of inscriptions is located 300m from the cave entrance, in an area along the managed footpath, within the historic cave tour zone (Figure 7). These inscriptions are located 10–15m overhead, on the flat ceiling of a wide and high section of the main passage. This area has many examples of historic graffiti on rock surfaces within reach of the tourist paths. Among these graffiti are isolated syllabary elements, which, as previously noted, are difficult to interpret. The more extensive syllabary texts on the ceiling, however, can be read, and they include several different inscription panels, all of which share some important characteristics. There is another, different signature here, this time written in Cherokee syllabary. As all of these ceiling inscriptions relate to sensitive religious subject matters, we will not present their complete translation here; instead, we consider their context as much as their content. We note that the charcoal signature of Richard Guess shown in Figure 5 is found in a low-down position on the cave wall, just across the main passage from these ceiling panels.

Figure 7. Beau Duke Carroll and Julie Reed in Manitou Cave, with Cherokee syllabary visible on the ceiling (photograph by A. Cressler).

One ceiling inscription (Figure 8), ![]() , reads A-yv-si-li-ta-s in Cherokee. In English, part of this statement is ‘I am your grandson’, which is how Cherokees might formally address ‘Old Ones’, or Cherokee ancestors (although this is not a literal translation). As the ‘Old Ones’ would typically be invoked via the sensitive contexts of prayer or medicinal formulae, our translations here will go no further. Next are two ceiling inscriptions with identical content. One is written in black charcoal (Figure 8). The other (Figure 9) was produced in a very similar manner to the engraved inscription discussed earlier: the ceiling was first prepared by sooting the bare limestone. A scalloped charcoal oval was then drawn, enclosing the blackened surface, and the inscription was engraved through the soot and into the limestone below, creating a ‘negative’ impression. While translation of this (and the previous) panel is challenging and ongoing, we think that the inscription reads

, reads A-yv-si-li-ta-s in Cherokee. In English, part of this statement is ‘I am your grandson’, which is how Cherokees might formally address ‘Old Ones’, or Cherokee ancestors (although this is not a literal translation). As the ‘Old Ones’ would typically be invoked via the sensitive contexts of prayer or medicinal formulae, our translations here will go no further. Next are two ceiling inscriptions with identical content. One is written in black charcoal (Figure 8). The other (Figure 9) was produced in a very similar manner to the engraved inscription discussed earlier: the ceiling was first prepared by sooting the bare limestone. A scalloped charcoal oval was then drawn, enclosing the blackened surface, and the inscription was engraved through the soot and into the limestone below, creating a ‘negative’ impression. While translation of this (and the previous) panel is challenging and ongoing, we think that the inscription reads ![]() , Gu-ga-su-s-go in Cherokee, which means, in part, ‘smoker’. This probably represents a person's ceremonial role name—the designated medicinal ‘smudger’ or ‘cleanser’ in a ritual activity.

, Gu-ga-su-s-go in Cherokee, which means, in part, ‘smoker’. This probably represents a person's ceremonial role name—the designated medicinal ‘smudger’ or ‘cleanser’ in a ritual activity.

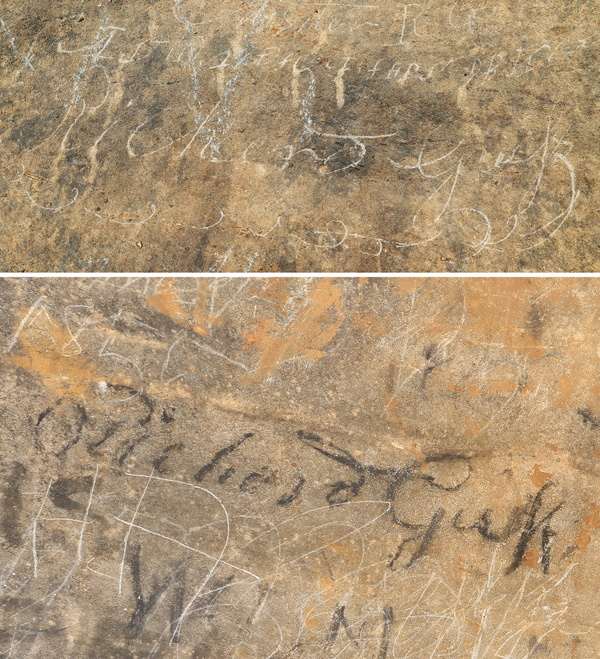

Figure 8. Syllabary ceiling inscriptions. Top) note signature of The Goose; bottom) compare with Figure 9 bottom (average element vertical height approximately 100mm) (photograph by A. Cressler).

Figure 9. Syllabary ceiling inscriptions incised over blackened surface. Top) sooted area within wavy charcoal outline; bottom) close-up of engraving into sooted surface. Compare text to Figure 8 bottom (average element vertical height approximately 100mm) (photograph by A. Cressler).

When comparing photographs of the ceiling writings and our text versions, it is evident that the ceiling inscriptions are written backwards, as if addressing readers inside the rock itself, rather than in the passage below. This contrasts with the writings deeper in the cave, where inscriptions are legible from the passage. We recorded several isolated syllabary elements along the main passage walls closer to the entrance that are also reversed. Why might these texts be oriented in this way? The answer may lie in the target audience for the inscriptions. As previously noted, the ceiling texts mention the ‘Old Ones’, a category of invisible spiritual beings. While Old Ones can include deceased Cherokee ancestors, they can also comprise other supernatural beings who inhabited the world before the Cherokee came into existence. Hence, the inverted writing on the ceiling could be explained if Manitou Cave was viewed as a portal to the spirit world—the words or phrases must be written backwards to be legible to spiritual residents (Mooney Reference Mooney1900). This is in agreement with the Cherokee perception of caves as powerful places.

The messages to the Old Ones are positioned high on the cave roof, above a small ledge that is at least three metres from the writing. It is therefore difficult to understand how they were made; perhaps ladders or scaffolding were used, although no archaeological evidence for this survives. Tom Belt, a member of the United Keetoowah Band of Cherokees and well versed in Cherokee ideology, suggests an explanation from a Cherokee perspective, which makes the notion of the spiritual power associated with the Manitou Cave inscriptions hard to ignore:

a long time ago people could do things that people today cannot. These people would have been extremely powerful and able to perform seemingly impossible feats such as flying. That we can't get up there doesn't mean that they couldn't (Tom Belt pers. comm.).

Finally, another signature appears among the ceiling inscriptions, this time written in syllabary. This signature (Figure 9), signed as ![]() , is the Cherokee proper name Sa-Sa, or ‘The Goose’. A person named The Goose is listed in the 1835 Cherokee Census as living beside the Coosawattee River in Georgia, 100km east of Manitou Cave and Willstown (movement among Cherokee communities over such distances was common in the mid nineteeth century). Little is known about The Goose, except that his name appears in syllabary in another cave to the north of Manitou Cave, where syllabary inscriptions record other secluded ceremonial activities. Like Richard Guess, he may have been a ceremonial leader. Perhaps The Goose could fly.

, is the Cherokee proper name Sa-Sa, or ‘The Goose’. A person named The Goose is listed in the 1835 Cherokee Census as living beside the Coosawattee River in Georgia, 100km east of Manitou Cave and Willstown (movement among Cherokee communities over such distances was common in the mid nineteeth century). Little is known about The Goose, except that his name appears in syllabary in another cave to the north of Manitou Cave, where syllabary inscriptions record other secluded ceremonial activities. Like Richard Guess, he may have been a ceremonial leader. Perhaps The Goose could fly.

Discussion and conclusions

The Cherokee syllabary inscriptions in Manitou Cave reflect the use of this great cavern as a place for seclusion, reflection and ceremony during perhaps the most stressful time in Cherokee history, when the people were forcibly and finally removed forever from their beloved homelands. Located in one of the principal Cherokee communities, the cave was used multiple times for ceremonial activity. The selection of the more remote areas of the cave may reflect the significance of the religious practices carried out there; it might also reflect the need for greater security and privacy due to communal conflicts between Cherokee traditionalists and more acculturated Cherokees associated with missionaries and other influences from the encroaching white culture. We know, for example, that Christian missionaries considered stickball as a threat to their influence (Zogry Reference Zogry2010: 67–70).

A deep and remote chamber in which the cave's underground stream emerges was used by a stickball team for requisite purification under the spiritual guidance of Sequoyah's son, Richard Guess, who left behind signed memorial inscriptions. Another chamber closer to the cave entrance was used by The Goose, a different spiritual practitioner who communicated there with the Old Ones. These were supernatural spirits, who inhabited the interior of the cave's walls and ceilings and whose location required The Goose to write his messages backwards and to elevate them to the highest areas of the passage roof. In this case, context rather than seclusion may have dictated the positioning of the inscriptions. There were apparent conventions in messaging in both of these cave areas, including surface preparation, a scalloped oval enclosing some messages (the meaning of which we do not understand), and both painted and engraved text. Finally, we have recorded other examples of syllabary—single or a few isolated elements—scattered throughout the passages, some of which are also written backwards. These may represent another type of messaging in the cave. Thus, ceremonial inscriptions in Manitou Cave seem to have entailed conventional practices, even when their message and context were different.

We conclude with two final observations. First, these examples of inscriptions indicate that caves were seen by Cherokees as spiritually potent places, where wall embellishment was appropriate in the context of ceremonial action. This is precisely how older cave drawings in the American Southeast have been viewed, some of which date back thousands of years and comprise representational and abstract motifs, rather than text (Simek et al. Reference Simek, Cressler, Douglas and Moyes2013). Manitou Cave shows continuity in how caves were seen and used by Southeastern Native American peoples into the removal period. This is not to say that Cherokees were the only people to communicate using cave walls. It does, however, confirm that parietal decorations reflected the ceremonial use of caves for active engagement with spiritual matters. These were sacred spaces rather than ‘art galleries’. This may be relevant to cave art around the world.

Our second conclusion is that an accurate and textured understanding of Manitou Cave would not be possible without close collaboration between Euro-American and Cherokee scholars. Euro-American archaeologists found and documented the inscriptions, while Cherokees determined their meaning and historic context in terms of Cherokee memory and experiences. This collaboration, we believe, has resulted in a better understanding of how caves were perceived by those that used them prior to European conquest; how caves related to the cultural and spiritual landscapes of those producing the inscriptions; how Manitou Cave reflected complex contemporaneous social and political changes; and what our findings mean to descendant communities today. Such a nuanced view of the archaeological record in Manitou Cave has required the active participation of indigenous scholars. Such collaboration is extremely productive and greatly enhances our interpretive possibilities.

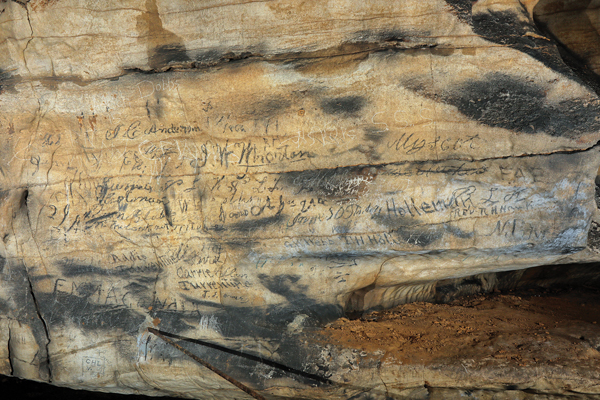

We end with a compelling irony. Figure 10 shows the wall immediately beneath The Goose's messages to the Old Ones. Hundreds of Euro-American signatures and tourist inscriptions cover the wall in this sacred location; these graffiti are also present in other parts of the cave. As for the Cherokees who lived around the cave, used its waters for sacred purposes and communicated with the spirit world inside, the overbearing imprint of the white usurpers has nearly overwhelmed the textual evidence for Cherokee voices. But it did not. The Goose's missives still soar above this modern mess. Richard Guess's signature is still visible across the passage. The Cherokees are still here despite murder and ethnic cleansing. Manitou Cave displays their cultural strength for all to see.

Figure 10. Euro-American graffiti below ceiling syllabary inscriptions (photograph by A. Cressler).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Annette Reynolds, steward of Manitou Cave, whose dedication and commitment to this site are unparalleled. In 2015, the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians (EBCI) contributed a strong steel gate at the cave entrance to protect the historic resources; Russell Townsend, EBCI Tribal Historic Preservation Officer, was instrumental in this process. Marion O. Smith, Kristen Bobo and Joseph Douglas made important contributions to this work. Research funding was provided by the Wenner-Gren Foundation and the Noyes Family Trust. We thank two anonymous reviewers for their helpful suggestions.