Chaco Canyon and its surrounding region is an iconic North American archaeological area. The canyon’s cluster of monumental architecture—especially Pueblo Bonito (Figure 1)—is a UNESCO World Heritage site and an archaeological crown jewel of the U.S. National Park Service. But what makes Chaco so intriguing to the public and archaeologists alike? Fowles (Reference Fowles2013: 79–81) characterises three main features that distinguish Chaco from other areas of the Southwest: its regionalism, extravagance and differentiation. While there are certainly continuities with antecedent societies of the Basketmaker III Period (c. AD 400–750) and those that followed in the post-Chaco period (c. AD 1120/1130–1300), it is the combination of these three characteristics that makes Chaco of the Bonito Phase (AD 800–1120/1130) of such great interest.

Figure 1 Multi-storey section in the East Wing of Pueblo Bonito (Room 242), Chaco Canyon National Historic Park. This room lies within the last major addition to the 800-room building, a construction episode that dates from AD 1077–1084. Dateable Pinus ponderosa roof beams and lintels in this room were cut between AD 1080 and 1082 and transported to Chaco from surrounding highlands. Two of the building’s seven corner doorways lead diagonally out of the second storey of this room to adjacent rooms, which made it one of the most connected rooms in Pueblo Bonito. The height of the ceiling of the second storey from the floor ledge (above the first-storey roof) is 2.9m (photograph by Barbara J. Mills).

Regionalism

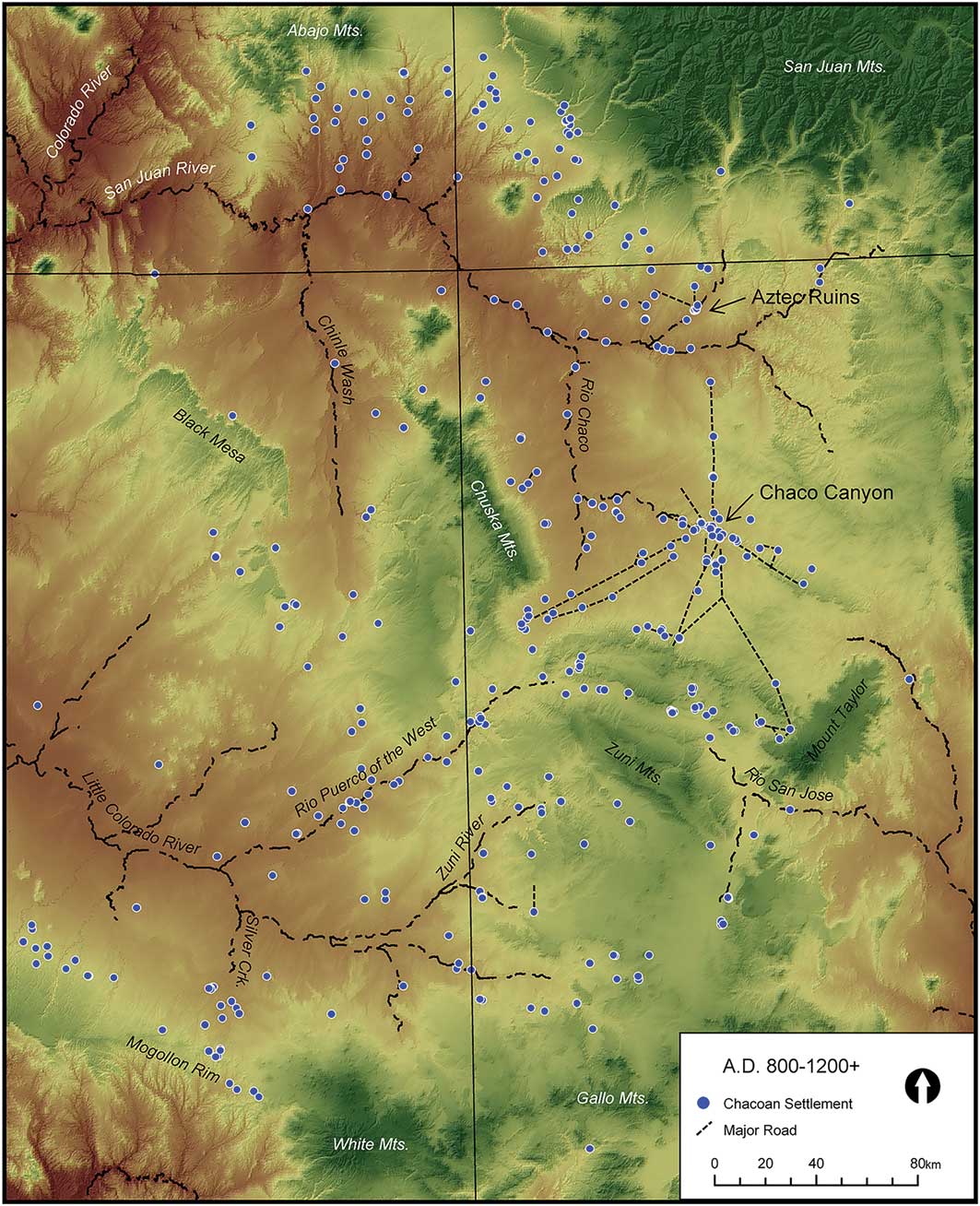

Chaco’s distinctive regionalism is defined by the evidence for extensive ties to the dense cluster of great and small houses within Chaco Canyon. This includes great houses dispersed over an area of more than 100 000km2 (Figure 2). Most of these are surrounded by smaller settlements, and may be associated with large-scale community architecture called great kivas and an array of other features (Gilpin Reference Gilpin2003; Lekson Reference Lekson2006; Van Dyke Reference Van Dyke2008). Road segments, causeways and staircases are found throughout the area, but are not continuous, raising questions about their purpose. Interpretations range from the transport of goods and people (including pilgrimage) to symbolic connectivity (e.g. Kantner & Vaughn Reference Kantner and Vaughn2012; Lekson Reference Lekson2015; Friedman et al. Reference Friedman, Sofaer and Weiner2017; Till Reference Till2017). Shared decorative designs on pottery, wood, stone and textiles were reproduced over this broad area, especially all-over hachure (known as Dogoszhi style), which Plog (Reference Plog2003) interprets as a metaphor for the colour turquoise.

Figure 2 Spatial extent of the Chaco World showing the distribution of great houses and great kivas (figure by Matthew A. Peeples).

Many of the items found within the canyon were imported, revealing Chaco’s connectivity with surrounding areas at different intensities and scales: pottery, flaked stone and trees from other parts of the San Juan Basin (e.g. Toll Reference Toll2006; Duff et al. Reference Duff, Moss, Windes and Kantner2012; Guiterman et al. Reference Guiterman, Swetnam and Dean2015; Crown Reference Crown2016a); turquoise and shell from more distant Southwestern locations (e.g. Mills & Ferguson Reference Mills and Ferguson2008; Thibodeau et al. Reference Thibodeau, Chesley, Ruiz, Killick and Vokes2012); and parrots, cacao and copper bells from Mesoamerica (Crown & Hurst Reference Crown and Hurst2009; Crown et al. Reference Crown, Gu, Hurst, Ward, Bravenec, Ali, Kebert, Berch, Redman, Lyons, Merewether, Phillips, Reed and Woodson2015; Watson et al. Reference Watson, Plog, Culleton, Gilman, LeBlanc, Whiteley, Claramunt and Kennett2015; Crown Reference Crown2016b; Nelson et al. Reference Nelson, Fish and Fish2017). The latter are interpreted as important for the symbolic legitimisation of Chaco’s leaders or aspirational leaders, who probably made the journey themselves to procure the goods (Nelson et al. Reference Nelson, Fish and Fish2017).

The extensive nature of Chaco’s reach has led to the usage of the term ‘Chaco World’ (Kantner Reference Kantner2003a; Kantner & Kintigh Reference Kantner and Kintigh2006). Starting with Kantner’s original compilation of great houses—now a part of the Chaco Research Archive (http://www.chacoarchive.org/cra/)—archaeologists working in the region have continued to collaborate on regional-scale databases of great houses and great kivas. Van Dyke et al. (Reference Van Dyke, Bocinsky, Windes and Robinson2016), for example, have deployed regional data in a GIS-platform to suggest that the intervisibility of landscape features, such as shrines, promoted regional connections, especially with Chaco Canyon. Bernardini and Peeples (Reference Bernardini and Peeples2015) show how ‘sight communities’ formed through shared views of distant topographic features (Figure 3). In this special section, Dungan et al. (Reference Dungan, White, Déderix, Mills and Safi2018) combine data on great houses and great kiva locations with total viewshed analyses to evaluate whether these structures were situated to promote more local, intracommunity visibility. They find that visibility was an important variable in great house placement, especially during the expansive AD 1000s. Their findings compare well with Kantner and Hobgood’s (Reference Kantner and Hobgood2016) viewshed analysis of tower kivas, which concluded that towers were built to be seen within, but not between, great house communities. Also in this section, Mills et al. (Reference Mills, Peeples, Aragon, Bellorado, Clark, Giomi and Windes2018) add material culture to a regional database to assess the changing structure of Chaco’s social networks.

Figure 3 Katherine Dungan recording a small house in the Kin Bineola community with Hosta Butte in background left (photograph by Barbara J. Mills).

Extravagance

Chaco’s extravagance is expressed through the consumption of larger quantities of materials than found in other Southwestern regions, and in the overbuilt character of its architecture (Figure 4). They are ‘overbuilt’ in the sense that great houses have core-veneer walls, carefully fitted masonry elements and multiple storeys. Our understanding of artefact density is based on materials from the two largest sites in the Chaco World—Pueblo Bonito in Chaco Canyon, and Aztec Ruins on the Animas River, 75km to the north. Pueblo Bonito’s Room 33 alone contained as much worked and unworked turquoise as recovered from any other site in the Southwest (Neitzel Reference Neitzel2003), and nearby Room 28 held more whole pottery vessels than any other single Southwestern context (Crown Reference Crown2018). More shell trumpets and macaws were recovered at Pueblo Bonito than at any contemporaneous Puebloan or non-Puebloan sites (Mills & Ferguson Reference Mills and Ferguson2008; Watson et al. Reference Watson, Plog, Culleton, Gilman, LeBlanc, Whiteley, Claramunt and Kennett2015; Crown Reference Crown2016b; Nelson et al. Reference Nelson, Fish and Fish2017). Even corn pollen was present in higher quantities within Chaco Canyon’s great and small sites than at other contemporaneous sites within the region (Geib & Heitman Reference Geib and Heitman2015).

Figure 4 Kin Bineola, a great house west of Chaco Canyon (photograph by Barbara J. Mills).

The labour used in architectural construction was also at a scale unprecedented in the Ancestral Pueblo area. Many of the construction episodes for great houses within and outside of Chaco Canyon were planned in advance, with timbers procured over long distances and stockpiled before construction, and buildings were multi-storeyed (Lekson Reference Lekson2007). As Crown and Wills (Reference Crown and Wills2018) discuss in this special section, Pueblo Bonito was being remodelled almost constantly. Such extravagance can be interpreted as building to impress both community members and visitors (Van Dyke Reference Van Dyke2008). Architectural extravagance included the construction of great kivas (10m or more in diameter) (Figure 5), which required large labour pools to procure the massive roof beams used in each structure. Dungan and Peeples (Reference Dungan and Peeples2018) show how a 17m-diameter great kiva in the southern Chaco area could have held as many as 189 people, approximately the number of people living in the dispersed communities surrounding the structure. Many of the unroofed Chaco kivas were even larger, holding 400–500 people (Dungan & Peeples Reference Dungan and Peeples2018). Coffey and Ryan (Reference Coffey and Ryan2017) interpret Chaco great kivas as the physical instantiation of Ancestral Pueblo communities.

Figure 5 Great kiva (Kiva Q) at Pueblo Bonito (photograph by Barbara J. Mills).

But what we now view as ‘extravagant’ may not have been viewed as such for those living at Chaco. The procurement of items from distant sources, their incorporation into buildings through dedication and termination, and the ceremonial closure of what appear to be storerooms of items used in religious ritual were all practices consistent with a society deeply connected to place (Mills Reference Mills2008; Plog & Heitman Reference Plog and Heitman2010). They are consistent with depositional practices that honoured ancestors and created a variety of regional social ties at varying distances and intensities. They must also be viewed in the context of significant social differentiation within the Chaco World, a process starting in the AD 800s and continuing for 300 years.

Differentiation

Chaco’s differentiation is both internal and external. Internally, it deviates from the organisation found in other contemporaneous Ancestral Pueblo regions, with evidence for early and sustained social inequality. Hierarchy is interpreted from the burial treatment of individuals within Pueblo Bonito compared with contemporaneous sites (Plog & Heitman Reference Plog and Heitman2010). Room 33’s collective interments—one of the few examples of collective burials in the Southwest—comprised 14 individuals interred with the copious funerary objects noted above. Two individuals were placed beneath a wooden plank floor, and above the floor was an array of co-mingled and disarticulated human remains. One of these individuals was polydactyl, as were two other individuals from Pueblo Bonito. Crown et al. (Reference Crown, Marden and Mattson2016) suggest that this was regarded as a sign of status. They document several cases of polydactylism among individuals in the Chaco World, depicted in rock art, painted on pottery and shaped into stone and ceramic objects. A set of six-toed footprints was embedded in the plastered walls of Room 28 (one of two rooms that accessed Room 33), where a unique assemblage of cylinder jars was found, and which were used for ceremonial drinking before the room was ceremonially burned (Sturm & Crown Reference Sturm and Crown2015; Crown Reference Crown2018).

There is increasing evidence that social inequality at Chaco began earlier than widely believed starting in the AD 800s for Room 33’s burials (Coltrain et al. Reference Coltrain, Janetski and Carlyle2007; Plog & Heitman Reference Plog and Heitman2010; Watson et al. Reference Watson, Plog, Culleton, Gilman, LeBlanc, Whiteley, Claramunt and Kennett2015; Kennett et al. Reference Kennett, Plog, George, Culleton, Watson, Skoglund, Rohland, Mallick, Stewardson, Kistler, LeBlanc, Whiteley, Reich and Perry2017). Marden (Reference Marden2015) suggests that the co-mingling of remains resulted from repeated access to the room for burial and possibly for the subfloor burials; offerings were deposited in the space above the plank floor for another two centuries. Recent aDNA analyses have revealed that individuals throughout the room were related through a single matriline that gained prominence in the AD 800s, continuing into the late AD 1000s, and perhaps the early AD 1100s (Kennett et al. Reference Kennett, Plog, George, Culleton, Watson, Skoglund, Rohland, Mallick, Stewardson, Kistler, LeBlanc, Whiteley, Reich and Perry2017). A second burial cluster in the western part of Pueblo Bonito may also have begun in the AD 800s (Plog Reference Plog2018). This cluster, too, had substantial burial accompaniments, suggesting the presence of a dual hierarchical organisation (Ware Reference Ware2014; Whiteley Reference Whiteley2015). Adjacent storage rooms containing items that were used in religious rituals clearly demonstrate that some of the authority of these elites came through their role as religious specialists (Mills Reference Mills2004, Reference Mills2008; Ainsworth et al. Reference Ainsworth, Crown, Jones and Franklin2018).

One aspect of Chaco’s heterogeneity that most archaeologists agree on is that people with different origins and backgrounds participated in the Chaco World. Migration and population replacement have been proposed for the central canyon (Wills Reference Wills2009). Archaeologists have long analysed variation among the outlying great houses in size, construction, layout and clustering, and emphasise that Chaco was not a single system, but multiple systems formed by the historical trajectories of individual communities (Kantner & Mahoney Reference Kantner and Mahoney2000; Kantner Reference Kantner2003b; Cameron & Duff Reference Cameron and Duff2008; Reed Reference Reed2008; Safi & Duff Reference Safi and Duff2016; Van Dyke et al. Reference Van Dyke, Bocinsky, Windes and Robinson2016).

It is increasingly apparent that ‘Chaco’ does not refer to a single ethnic or political group (Cameron Reference Cameron2005). The Chaco World included people with different backgrounds, agricultural technologies, leadership strategies, religious practices and, probably, languages. The use of the term ‘Chaco’ is usually in reference to the shared use of monumental architecture (great houses and great kivas), the presence of social inequality and some overarching religious and technological practices. These attributes were not evenly distributed and changed over the 300-year occupation. Understanding how migrants from different areas came together in Chaco communities is the subject of extensive research focused on technological and religious practices and their relationship to identities at various scales (Mills Reference Mills2008, Reference Mills2015; Wills Reference Wills2009; Duff & Nauman Reference Duff and Nauman2010; Clark & Reed Reference Clark and Reed2011; Reed Reference Reed2011a & Reference Reedb; Webster Reference Webster2011; Windes Reference Windes2014; Brown & Paddock Reference Brown and Paddock2015; Jolie & Webster Reference Jolie and Webster2015; Mattson Reference Mattson2016).

Several archaeologists suggest that Chaco’s early great houses resulted from the migration of Northern San Juan residents (Wilshusen & Van Dyke Reference Wilshusen and Van Dyke2006; Windes & Van Dyke Reference Windes and Van Dyke2012; Wilshusen Reference Wilshusen2015; Windes Reference Windes2015). Human isotopic variation, however, suggests that Chaco Canyon’s populations came from multiple areas, but probably not from the Northern San Juan (Price et al. Reference Price, Plog, LeBlanc and Krigbaum2017). Others point out that the earlier Basketmaker III (c. AD 500–750) occupation of Chaco Canyon has been underestimated (Wills et al. Reference Wills, Worman, Dorshow and Richards-Rissetto2012), and that there are similarities in the forms and technological styles of Basketmaker III ritual objects from Pueblo Bonito and contemporaneous sites to the west and south-west (Webster et al. Reference Webster, Cordell, Hays-Gilpin and Jolie2014). Even Chaco communities outside of the canyon are considered multi-ethnic (Murrell & Unruh Reference Murrell and Unruh2016).

Two papers in this special section directly address Chaco’s origins and diversity. Crown and Wills’s (Reference Crown and Wills2018) excavations at Pueblo Bonito, combined with their careful perusal of prior excavation records, point to an earlier Basketmaker III occupation underneath the building, suggesting local continuity. Mills et al. (Reference Mills, Peeples, Aragon, Bellorado, Clark, Giomi and Windes2018) also examine Chaco origins, through ceramic networks, concluding that there is little evidence for northern founders. Instead, they suggest areas south and west, as have researchers working on the provenance of timbers (Guiterman et al. Reference Guiterman, Swetnam and Dean2015). While people from the Northern San Juan may not have founded Chaco, evidence supports their incorporation into the Chaco World by the AD 1000s, and later migration into the central canyon (Wills Reference Wills2009; Mills et al. Reference Mills, Peeples, Aragon, Bellorado, Clark, Giomi and Windes2018).

Feeding Chaco

While Chaco’s extravagance has fostered archaeological interpretations of religious ritual, it is clear that religion, politics and economics should be integrated in a holistic approach. How Chaco families in the canyon and in the surrounding areas provisioned themselves is an important topic. Fundamentally, Chacoans were farmers who needed to understand climate, water flow, the interaction of storage and periodicity of drought, and when to move or stay in place (Cordell et al. Reference Cordell, Van West, Dean and Muenchrath2007). The programmes of great house additions and new outlier constructions, especially prominent in the AD 1000s, would have required large labour pools. Population estimates, however, are widely divergent (Minnis Reference Minnis2015; Plog Reference Plog2018); the degree of local contribution to labour is therefore unknown. It is also uncertain whether Chaco Canyon was a destination for pilgrims (Toll Reference Toll2001; Van Dyke Reference Van Dyke2008; Kantner & Vaughn Reference Kantner and Vaughn2012) or not (Plog & Watson Reference Plog and Watson2012). Regardless, hospitality during ceremonial events would have been an important part of life in the canyon, given the density of evidence for hierarchy and religious ritual. Chaco Canyon gatherings may have included ritualised gaming practices, such as gambling (Weiner Reference Weiner2018).

It has long been assumed that the highlands defining the San Juan Basin offered greater potential to support crops and animals than Chaco Canyon. Along with the importation of timber and pottery (Toll Reference Toll2006; Guiterman et al. Reference Guiterman, Swetnam and Dean2015), it is suggested that corn and game animals were also transported to the canyon (e.g. Benson Reference Benson2012; Grimstead et al. Reference Grimstead, Quade and Stiner2016). Re-analyses of the isotope data have challenged the transport of corn and small mammals, however, because of the presence of significant geological, hydrological and elevational variation within the canyon and its surroundings (Hamilton et al. Reference Hamilton, Drake, Wills, Jones, Conrad and Crown2017; Price et al. Reference Price, Plog, LeBlanc and Krigbaum2017). Furthermore, it does not appear that salinity would have been a problem for Chaco farmers (Tankersley et al. Reference Tankersley, Dunning, Thress, Owen, Huff, Fladd, Bishop, Plog, Watson, Carr and Scarborough2016; but see Benson 2017). Nonetheless, the procurement of large animals from upland areas is indicated by rainfall and isotopic variation (Grimstead et al. Reference Grimstead, Quade and Stiner2016, Reference Grimstead, Pailes and Kyle Bocinsky2017). New research modelling the maize niche from a large-scale dendroclimatological database (Bocinsky et al. Reference Bocinsky, Rush, Kintigh and Kohler2016) offers potential for future studies of human-environment interaction.

Other research on Chaco technology and productivity focuses on the agricultural potential of the central canyon and surrounding areas. It is argued that sufficient food production was achieved by employing technologies, such as water-diversion features, canals, sand dune farming, ak chin fields and gridded gardens (Worman & Mattson Reference Worman and Mattson2010; Dorshow Reference Dorshow2012; Wills & Dorshow Reference Wills and Dorshow2012; Wills et al. Reference Wills, Drake and Dorshow2014, Reference Wills, Love, Smith, Adams, Palacios-Fest, Dorshow, Murphy, Mattson and Crown2016; Vivian & Watson Reference Vivian and Watson2015; Sturm Reference Sturm2016; Wills Reference Wills2017). Wills (Reference Wills2017) suggests that the evidence for agricultural features combined with dispersed fields surrounding the canyon would have been sufficient to support the labour required for great house construction, without needing to generate large surpluses. It was in the granting of permission to farm that the relations of production were built, rather than in extracting surplus. While Wills’s interpretation balances what seems to be limited evidence for large-scale agricultural features with the canyon’s architectural density, Scarborough et al. (Reference Scarborough, Fladd, Dunning, Plog, Owen, Carr, Tankersley, McCool, Watson, Haussner, Crowley, Bishop, Lentz and Gwinn2018) provide documentation of a previously unrecognised larger canal system. They conclude that this irrigation system would have required coordination and, importantly, it represented a strategy for increasing resilience in an unpredictable climate.

Chaco in comparative perspective

Lekson (Reference Lekson2009) and Drennan et al. (Reference Drennan, Peterson and Fox2010) have chastised Southwest archaeologists for claims of exceptionalism and called for more comparative studies (Schachner Reference Schachner2015: 57–59). Schachner (Reference Schachner2015: 57) points out that Drennan et al .’s (2010) study compares Chaco to Early Olmec, Moundville and Formative Oaxaca, among other New World societies. Lekson (Reference Lekson2009, Reference Lekson2017) is the most vociferous in his support for differences between Chaco and descendant Pueblo societies, rejecting the use of ethnographic analogy as a comparative tool. By contrast, Ware (Reference Ware2014) argues that we will never comprehend Chaco until archaeologists better understand contemporaneous Pueblo social organisation—especially kinship (see also Hays-Gilpin & Ware Reference Hays-Gilpin and Ware2015; Whiteley Reference Whiteley2015). Many of these reconstructions are dependent on population size, which remains difficult to evaluate (Plog Reference Plog2018); current estimates range from 10 000–200 000 (with most between 20 000–50 000) persons in the entire Chaco World at its peak in the tenth and eleventh centuries AD (Minnis Reference Minnis2015).

In its degree of hierarchy, social organisation during the Chaco period was different from later Pueblos, and from Chaco’s contemporaries in other areas of the Southwest. This is one of the most important changes in Chaco scholarship of recent years (including my own). Models that take this into account include small-scale states occupied by kings and queens, chiefdoms and Lévi-Straussean house societies (Heitman & Plog Reference Heitman and Plog2005; Heitman Reference Heitman2007, Reference Heitman2015; Mills Reference Mills2008, Reference Mills2015; Lekson Reference Lekson2009; Plog & Heitman Reference Plog and Heitman2010; Plog et al. Reference Plog, Heitman and Watson2017). As a key global case study in the emergence of inequality, Chaco has much to contribute to comparative studies. What are needed, however, are data on many of the variables that go into analysing such comparisons. The papers in this special section help move Chaco archaeology towards that goal.

Acknowledgements

Thanks go to the editors of Antiquity for facilitating this special section, and to the authors for their contributions. My understanding of Chaco was initiated by fieldwork under the direction of the late Robert P. Powers. It has continued through interaction with many individuals too numerous to name, but most recently by members of the Chaco Social Networks Project group (NSF grant #1355374). I am grateful for the comments of Jeffery Clark, Patricia Crown, Katherine Dungan, Evan Giomi and T.J. Ferguson on this manuscript.