According to the results of the 2021 Nationally Consistent Collection of Data on School Students with Disability (NCCD), 21.8% of students enrolled in Australian schools have a disability that influences their access to schooling. Of these students, almost 15% require a level of support beyond quality differentiated teaching practice (Australian Curriculum, Assessment and Reporting Authority [ACARA], 2021). Current legislation and system policy maintain that the majority of these students should be educated in their local schools unless there is a valid reason for an alternative. Yet government figures show special schools now comprise a higher percentage of the schooling sector than they did 10 years ago (from 4.37% in 2010 to 5.21% in 2020; ACARA, 2021), and, unsurprisingly, more students are enrolled in special schools now than were in 2003 (an increase of 1% of the total student population; Australian Institute of Health and Welfare [AIHW], 2020).

The Royal Commission into Violence, Abuse, Neglect and Exploitation of People with Disability (2021; hereafter referred to as the Disability Royal Commission) recently released an unfavourable report reflecting on the state of education (after the conclusion of Public Hearing 7) aptly titled ‘Barriers Experienced by Students With Disability in Accessing and Obtaining a Safe, Quality and Inclusive School Education and Consequent Life Course Impacts’. The report investigated students’ access to inclusive education and consequent life course influences. The Disability Royal Commission found there are still ‘significant barriers experienced by students with disability in accessing safe, quality and inclusive education in mainstream settings’ (p. 33) and highlighted issues such as denial of enrolment, increased rates of bullying, inadequate provision of adjustments, and increased rates of disciplinary absences as some common barriers.

Although several issues were emphasised, it was considered worthwhile to explore the barriers to the implementation of reasonable adjustments, which are described as measures and actions that have been adopted in Australia to assist students with disability to participate in their learning on the same basis as their peers (Australian Government, 2005). For clarity, (reasonable) adjustments are a separate construct to modifications, which change what is learned; and, accordingly, modifications did not form part of this scoping review. We prioritise reasonable adjustments because the authors, as teacher educators, believe that we have both the capacity and an obligation to make an impact on the inclusion space. The present scoping review is designed to explore the potential enablers and barriers to the implementation of reasonable adjustments to define future research directions to inform the use of reasonable adjustments and how we, as teacher educators, can ensure every student is offered the opportunity to learn to their potential. We commence the scoping review by framing the problem of interpretation of inclusive education legislation in Australia and internationally. Next, we address the significance of reasonable adjustments in schools and detail their function and importance. An outline of our method and search strategy for the scoping review is then provided. Results highlight themes about the enablers and barriers identified for teacher practice in Australian classrooms. We offer important considerations for stakeholders and practitioners around the successful implementation of reasonable adjustments in schools for students with disability.

Rationale

The United Nations (2006) Convention on the Rights of Persons With Disabilities considers inclusive education to promote equal access to education in the local community, and this approach has been enacted in Australia (Australian Government, 2005). Inclusion is based on the social interactionist model that considers the person and their environment to influence participation (Dally et al., Reference Dally, Dempsey, Ralston, Foggett, Duncan, Strnadova, Chambers, Paterson and Sharma2019). Inclusive education in Australia and internationally, however, has experienced a long and contentious history where policymakers, advocates and practitioners have struggled with what inclusive education looks like (in policy and definition), sounds like (in the advocacy of placement), and feels like (in classroom practice). To date, there is a lack of a globally accepted definition for inclusive education, and this challenge presents many barriers when applying the concept of inclusive education, assessing its forward movement, or evaluating its success (Anderson & Boyle, Reference Anderson and Boyle2015; Duncan et al., Reference Duncan, Punch, Gauntlett and Talbot-Stokes2020, Reference Duncan, Punch and Croce2021).

In the Australian context, inclusive education means that all students are welcomed by their school in age-appropriate settings and are supported to learn, contribute and participate in all aspects of school (Australian Government, 2005). The intention of this definition is that all students are supported in the same classroom; however, the application of this definition lends itself to the interpretation where parents, on behalf of their children, can elect to enrol their child in a special school or specialist support setting. The Disability Royal Commission (2021) suggested that one answer to the question as to why parents are willing to choose this education option is that they are avoiding the difficulties of mainstream classes to deliver a quality educational experience for their children.

As a result, in Australia, only 71% of children with a disability attend mainstream classes, 18% attend specialised classes in a mainstream school, and 12% attend schools with the specific purpose of educating children with disabilities (AIHW, 2020). One implication of this supposed dual education system is the risk of teachers in mainstream classes, as well as parents, having an alternative option for the placement of students that offers the possibility of a reprieve from the challenges of implementing effective inclusive education strategies when students with disability are no longer their responsibility (Mann et al., Reference Mann, Cuskelly and Moni2018).

As defined by the AIHW, just over half (59%) of students with profound and multiple disabilities reportedly attend classes in a mainstream school (AIHW, 2020). One reason for the motivation to enrol students in mainstream settings is in regard to the more positive or perceived wellbeing and learning benefits in a specialist setting; however, as students age, the appropriateness of regular settings becomes less fitting (Byrne, Reference Byrne2013; Mann et al., Reference Mann, Cuskelly and Moni2018). Many, however, choose to shift their child to a special school setting based on potential negative influences on learning and wellbeing, which increases as the student increases in age (Byrne, Reference Byrne2013; Mann et al., Reference Mann, Cuskelly and Moni2018). The association between negative classroom experiences for students with disability and the lack of preparedness mainstream teachers feel to teach a range of learning needs has been noted (Dally et al., Reference Dally, Dempsey, Ralston, Foggett, Duncan, Strnadova, Chambers, Paterson and Sharma2019; Duncan & Punch, Reference Duncan and Punch2021; Duncan et al., Reference Duncan, Punch and Croce2021; Forlin et al., Reference Forlin, Sin and Maclean2013), leading to reports by teachers of low confidence and low satisfaction when teaching students with disability (Vermeulen et al., Reference Vermeulen, Denessen and Knoors2012).

Conversely, teacher training and targeted professional development have been identified as key components of high-quality inclusive education and teaching practices (Forlin et al., Reference Forlin, Sin and Maclean2013). One strategy that is not only mandated but also regarded as essential within teacher training and professional development for successful inclusive practice is to make adjustments in the school setting to support learning for all students.

The Australian Disability Standards for Education 2005 (DSE; Australian Government, 2005) was developed to guide non-discrimination in education. The DSE is the application to education of the Disability Discrimination Act 1992 (Australian Government, 1992). Under this legislation, the DSE states that schools are responsible for making reasonable adjustments to provide children with disabilities with education on the same basis as their peers (Australian Government, 1992). The NCCD indicates that data taken in 2021 revealed that over 50% of students requiring a level of adjustment had a cognitive disability, 31% had social–emotional disorders, 11% physical disability, and 3% were reported to have a sensory disability (ACARA, 2021). Most of these students were provided with supplementary adjustments (42.5%), followed by differentiated teaching practice (32.6%), and substantial (16.8%) and extensive (8.1%) adjustments (ACARA, 2021).

Adjustments are deemed ‘reasonable’ when they are the ‘product of consultation and [seek] to balance the interest of all parties’ (NCCD, 2021, para. 2). In deciding whether the adjustment is reasonable, the following considerations are applicable:

the influence of the disability on the student’s learning, participation, and independence;

views of the student with disability, or their associate, about their preferred adjustment;

influence of the adjustment on relevant parties, such as other students, staff members, the student’s family, and the education provider;

costs and benefits of making the adjustment; and

the need to maintain the essential requirements of the course or program (NCCD, 2021, para. 12).

In practice, some examples of reasonable adjustments in schools include providing access to classroom materials through the availability of assistive technology devices such as screen readers; installing modifications for students with mobility challenges; modifying assessments to allow students to answer verbally when writing is a difficulty; or, outside of the classroom, planning excursions that are accessible for all students (e.g., accessible toilets and ramps; Department of Education, 2022).

The application of reasonable adjustments appears, on the surface, to be a common-sense approach for students with disability, where their disability or an aspect of their disability prevents equitable access to their participation in education. For example, to provide a ramp to access the classroom for students with mobility issues and clear corridors within the classroom to move around in a wheelchair is prudent based on the simple perceptions of the situation.

Unfortunately, the implementation of reasonable adjustments in Australia has been shrouded in controversy. Researchers such as Foreman and Arthur-Kelly (Reference Foreman and Arthur-Kelly2008), Forlin et al. (Reference Forlin, Sin and Maclean2013), and Punch (Reference Punch2015) have reported that, despite the realisation that educational inclusion requires the implementation of reasonable adjustments, teachers are failing to apply reasonable adjustments in classrooms. Further, reasonable adjustments that were implemented were actioned by support staff rather than trained teachers (Punch, Reference Punch2015). Additionally, the lack of guidelines to assist schools in determining a reasonable adjustment has been highlighted (Duncan et al., Reference Duncan, Punch, Gauntlett and Talbot-Stokes2020; Poed, Reference Poed2015). Significantly, the most controversial aspect of applying reasonable adjustments is interpreting what is deemed ‘reasonable’. Schools are not required to implement an adjustment if it is seen as unreasonable or if compliance would impose unjustifiable hardship on the school (e.g., if the required reasonable adjustments would incur high costs).

Of note, although the DSE mandates reasonable adjustments, ‘inclusive education’ as a construct or legitimate term is not mandated (Duncan et al., Reference Duncan, Punch and Croce2021). The inherent message is diminishing the importance of any scrutiny to ‘systems through the lens of what constitutes a “good education” for all students’ (Boyle & Anderson, Reference Boyle, Anderson, Sharma and Salend2020, p. 16). By positioning reasonable adjustments in this manner, there is a risk that reasonable adjustments become merely a compliance issue for schools rather than a meaningful mechanism to enable equal educational access. It remains the responsibility of each school to implement reasonable adjustments and determine what, where and how they look (Cumming et al., Reference Cumming, Dickson and Webster2013). Often schools implement reasonable adjustments inconsistently, and the adjustments that are made occur as a reactive rather than as a pre-emptive measure (Mavropoulou et al., Reference Mavropoulou, Mann and Carrington2021).

Perhaps because of vague guidance and the subsequent inconsistent application of reasonable adjustments across schools, there is minimal evidence-based research in Australia to support the appropriateness or application of making adjustments for students with disability. Evidence-based outcomes in this field are also problematic, as reasonable adjustments are measured as discrete adjustments. One example of a reasonable adjustment that provides empirical evidence is to differentiate teaching practice (Du Plessis & Ewing, Reference Du Plessis and Ewing2017). Other examples of a direct application of reasonable adjustments include assessment adjustments, such as extra time, and physical adjustments, such as the addition of ramps. The efficacy of reasonable adjustments as a systematic framework is yet to be realised, which offers the possibility for future research in this area.

Objectives

The purpose of this scoping review was to investigate and then map and explore literature in a field of research that originates in a wide range of sources (Cooper et al., Reference Cooper, Cant, Kelly, Levett-Jones, McKenna, Seaton and Bogossian2021). It was framed within an a priori protocol and involved a replicable systematic search of the literature (Tricco et al., Reference Tricco, Lillie, Zarin, O’Brien, Colquhoun, Levac, Moher, Peters, Horsely, Weeks, Hempel, Aki, Chang, McGowan, Stewart, Hartling, Aldcroft, Wilson, Garritty and Straus2018). In this scoping review, we investigated and compared the literature to provide direction for educators on the implementation of reasonable adjustments in schools. The review aimed to address the issues relevant for students with disability concerning their access to learning on the same basis as their peers. The research question was as follows: What are the enablers and barriers for teacher practice in making reasonable adjustments in mainstream primary and secondary school classrooms in Australia?

Methods

For this scoping review, we employed an approach to identify key concepts relating to the research questions. This is consistent with the framework articulated by Peters et al. (Reference Peters, Godfrey, Khalil, McInerney, Parker and Soares2015) and Tricco et al. (Reference Tricco, Lillie, Zarin, O’Brien, Colquhoun, Levac, Moher, Peters, Horsely, Weeks, Hempel, Aki, Chang, McGowan, Stewart, Hartling, Aldcroft, Wilson, Garritty and Straus2018), where clarification over definitions and understandings of the conceptual boundaries reading the research question is established. The first step in this process was identifying the objectives and research question. Second, key search items were then developed through a preliminary search. Finally, a review protocol was developed where data were extracted from included studies. Data were then taken from those studies to answer the research question.

Eligibility Criteria

To be included in the present review, studies had to meet the following four criteria: (a) investigated reasonable adjustments in Australian primary and secondary mainstream classrooms; (b) were research-based, literature reviews, case studies, or scoping reviews; (c) were published from 2005 to 2021 to capture the relevant literature published after the introduction of the DSE; and (d) were published in peer-reviewed journals.

Conversely, the criteria for exclusion were publications that (a) investigated reasonable adjustments in countries other than Australia; (b) investigated reasonable adjustments in early childhood settings, post-secondary settings, schools for specific purposes, or health settings; (c) were grey literature; and (d) were not peer reviewed.

The authors were cognisant of the potential limitation of excluding research from countries other than Australia, but felt it essential to capture the domestic zeitgeist as an initial scan. We applaud universal design, accessibility and reasonable accommodation (adjustments) as a core tenet of the United Nations Disability Inclusion Strategy (United Nations, 2019) and look forward to enabling a global lens in future publications.

Search Strategy

A three-stage systematic search strategy was employed using five databases: EBSCO, ProQuest, Social Work Abstracts, Informit, and Scopus. In Stage 1, eight search terms were used to identify implementation of the DSE: reasonable adjustments, modifications, accommodations, adjustments, provisions, differentiation, changes, and adaptations. Five search terms were used to identify the school setting (i.e., school, education, inclusive education, special needs, special needs education). Truncations of ‘disability’ and ‘impairment’ identified students with disability, and the search targeted articles from Australia.

In Stage 2, the following search strategy was used to identify articles relevant to the enablers and barriers to reasonable adjustments in primary and secondary mainstream classrooms: [reasonable adjustments OR modifications OR accommodations OR adjustments OR provisions OR differentiation OR changes OR adaptations] in All Text AND [disab* OR impair*] in Subject AND [school OR education OR inclusive education OR special needs OR special needs education OR primary education OR secondary education] in Subject AND [Australia*] in Abstract.

In Stage 3, an analysis of the title, abstract and index references of relevant papers was completed. Additionally, an ancestral search (to determine whether records were identified from reference lists of relevant articles or literature reviews) was conducted of references of relevant articles. In total, the three-stage search strategy yielded 25 included articles. Article selection adhered to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analysis Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) model (Tricco et al., Reference Tricco, Lillie, Zarin, O’Brien, Colquhoun, Levac, Moher, Peters, Horsely, Weeks, Hempel, Aki, Chang, McGowan, Stewart, Hartling, Aldcroft, Wilson, Garritty and Straus2018).

Before finalising the included article content analysis, a post hoc search of the literature was conducted to ensure recent studies were captured, which resulted in one additional article. Figure 1 illustrates the process of selection of articles for each of the three stages.

Figure 1. Article Selection Process as Recommended by the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analysis Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) Model (Tricco et al., Reference Tricco, Lillie, Zarin, O’Brien, Colquhoun, Levac, Moher, Peters, Horsely, Weeks, Hempel, Aki, Chang, McGowan, Stewart, Hartling, Aldcroft, Wilson, Garritty and Straus2018).

Content Analysis

Thematic analysis was completed using Braun and Clarke’s (Reference Braun and Clarke2006, Reference Braun and Clarke2022) six-stage procedure, which adopts the process of initial coding and interrater reliability checks (Braun et al., Reference Braun, Clarke, Hayfield, Terry and Liamputtong2019). Initially, coding was completed via NVivo 12 software (QSR International, 2020) and manual coding occurred for reliability measures. In all, five main themes and 11 subthemes were identified (see Figure 2).

Figure 2. Themes and Subthemes.

Identification

This scoping review follows the framework detailed by the Joanna Briggs Institute (Peters et al., Reference Peters, Godfrey, McInerney, Munn, Tricco and Khalil2020), which endorses the PRISMA-ScR decision flow chart (Tricco et al., Reference Tricco, Lillie, Zarin, O’Brien, Colquhoun, Levac, Moher, Peters, Horsely, Weeks, Hempel, Aki, Chang, McGowan, Stewart, Hartling, Aldcroft, Wilson, Garritty and Straus2018).

Results

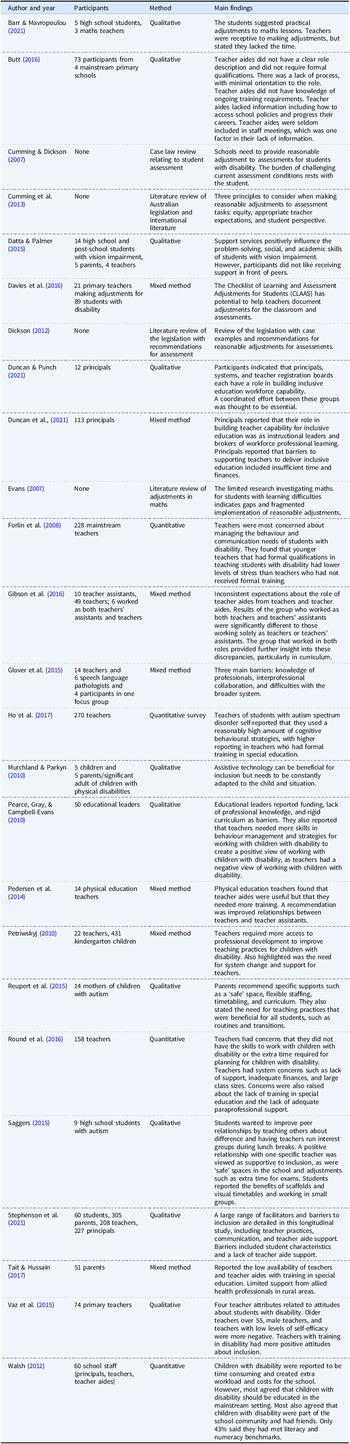

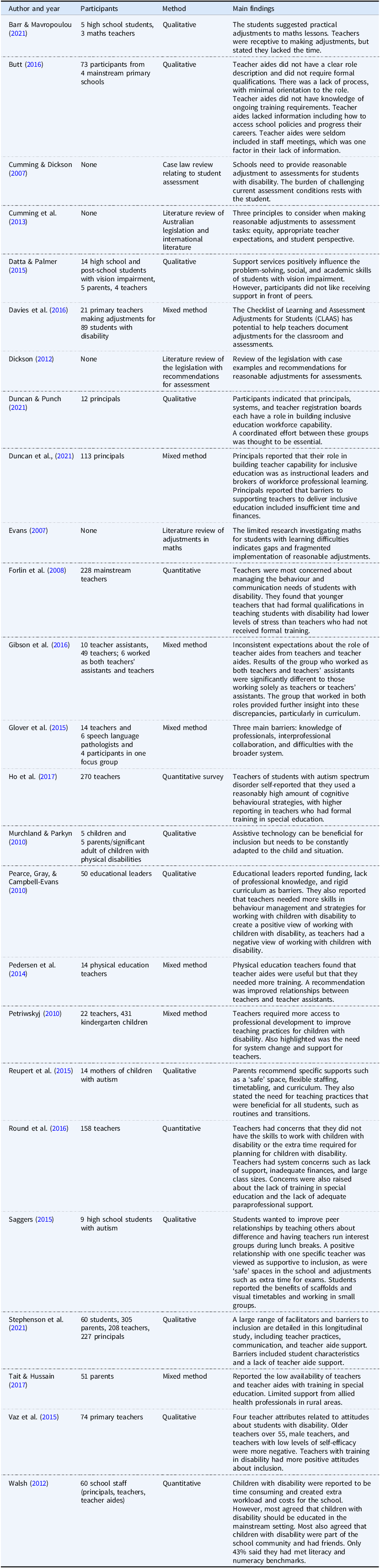

The summary in Table 1 outlines the overview of the peer-reviewed studies included in the scoping review. The 25 included articles provided in Table 2 show the results for authors, year, participants, and main findings. Of note, four were literature reviews, three related to a review of legislation, and one reviewed mathematics assessment.

Table 1. Terms Used to Identify Articles for Boolean Search Strategy

Table 2. Included Articles

The resultant themes that responded to the research question — What are the enablers and barriers for teacher practice in making reasonable adjustments in mainstream primary and secondary school classrooms in Australia? — are explained in detail as follows. We have summarised these themes under their relevant subthemes to best present the complex factors within the findings.

Legislative System

Legislative systems refer to national and local policy and acts governing the legal obligations that need to be met. Two areas were identified relating to legislation and policy in the reviewed articles. One theme was linked with the relationship between policy and its impact in schools, and the other theme pertained to issues of national funding and in what ways schools subsequently received funding to implement reasonable adjustments within the school environment.

Policy and school governance

Guidance from national policy filtering down to school governance was regarded as paramount in steering the implementation of reasonable adjustments (Duncan & Punch, Reference Duncan and Punch2021; Duncan et al., Reference Duncan, Punch, Gauntlett and Talbot-Stokes2020). Although school staff sought clarification of the rules and regulations to assist with the implementation of reasonable adjustments, as Dickson (Reference Dickson2012) pointed out, schools cannot wait for a complaint of discrimination to be made before remedying practices and policies that affect the educational opportunities of students with disability. Thus, a dilemma is created between policy and application of policy because of vague national guidelines.

Funding

Pearce, Gray, and Campbell-Evans’s (Reference Pearce, Gray and Campbell-Evans2010) findings summarise that access to learning was reported to be affected by funding, where insufficient funds and reductions in funding led to the decreased capacity to effectively resource reasonable adjustments. The impact of increasing numbers of students identified to require reasonable adjustments is not being matched by the availability of, for example, wages to employ additional support staff (Pearce, Gray, & Campbell-Evans, Reference Pearce, Gray and Campbell-Evans2010). There were several instances that were cited where parents augmented the cost of supporting their children (Dickson, Reference Dickson2012). Funding was particularly problematic in secondary schools, where it was noted that funding diminished as students moved from primary to secondary school, in the misguided belief that as students grew older, less support would be needed (Pearce, Gray, & Campbell-Evans, Reference Pearce, Gray and Campbell-Evans2010).

School Environment

The second theme identified spoke to issues of the classroom and aspects of the school environment and structure. The first of these was the class size.

Class context

Several articles reported the effect of class size on ease of implementing reasonable adjustments. Small class sizes facilitated application of reasonable adjustments compared to larger class sizes (Vaz et al., Reference Vaz, Wilson, Falkmer, Sim, Scott, Cordier and Falkmer2015). Teachers expressed concerns about accommodating the needs of students with disability in a regular class size, as this placed an extra burden on their capacity to effectively meet all learning needs (Barr & Mavropoulou, Reference Barr and Mavropoulou2021; Forlin et al., Reference Forlin, Keen and Barrett2008). The implementation of reasonable adjustments at a secondary school level was problematic not only because of reduced funding but also because the practicality of applying reasonable adjustments in the secondary school was questioned by school leaders (Pearce, Gray, & Campbell-Evans, Reference Pearce, Gray and Campbell-Evans2010). One author reported on the challenges of implementing reasonable adjustments as students became older, and this was also the case in primary school, where it was considered easier for teachers to implement reasonable adjustments at kindergarten level rather than at the upper levels of primary school (Petriwskyj, Reference Petriwskyj2010). One reason cited by Pearce, Campbell-Evans, and Gray (Reference Pearce, Campbell-Evans and Gray2010) was that secondary teachers required professional development in pedagogical skills and knowledge to be able to make the necessary reasonable adjustments within their teaching and learning.

System flexibility

Flexibility of systemic approaches was reported as beneficial and enabled by support by leadership and ancillary support staff (Petriwskyj, Reference Petriwskyj2010). Contrarily, when systems were rigid, teachers found difficulties in meeting system requirements such as processes of data collection and paperwork that were sometimes incongruous with meeting the needs of students (Duncan et al., Reference Duncan, Punch and Croce2021).

School leadership

There was a relationship between governance of policy and an inclusive culture when principals had a clear direction of what and how to implement reasonable adjustments (Duncan & Punch, Reference Duncan and Punch2021; Duncan et al., Reference Duncan, Punch and Croce2021). Principals were also responsible for promoting a positive inclusive culture that influenced the perception around, and the delivery of, reasonable adjustments. The role of principals was also to support teachers and monitor their capabilities so that students could be fully accommodated in mainstream classrooms (Duncan & Punch, Reference Duncan and Punch2021; Duncan et al., Reference Duncan, Punch and Croce2021). Duncan and Punch (Reference Duncan and Punch2021) and Duncan et al. (Reference Duncan, Punch and Croce2021) reported that principals described their role as curators of professional learning so that the workforce understood how to meet individual student need, how to differentiate teaching and learning, and how to accommodate all students’ learning goals. The role of the principal as a facilitator of reasonable adjustment practice was also reported by Pearce, Gray, and Campbell-Evans (Reference Pearce, Gray and Campbell-Evans2010).

Classroom Environment

The significance of the classroom environment was relevant to the discussion about reasonable adjustments in that the literature spoke of the nuances between the various roles that the staff played in relationship with their skills and experiences. In turn, the effectiveness of reasonable adjustment practice was influenced by the availability and/or access to resources within this environment.

Teacher role and responsibility

Although Walsh (Reference Walsh2012) and Round et al. (Reference Round, Subban and Sharma2016) reported that most teachers agree with the intention of inclusion, several authors identified in the scoping review reported on negative teacher attitudes that influenced the implementation of reasonable adjustments. Barr and Mavropoulou (Reference Barr and Mavropoulou2021) state that lack of time was reported in every teacher interview conducted. Issues of workload were also raised by Forlin et al. (Reference Forlin, Keen and Barrett2008), where teachers stated that there was insufficient non-contact time to develop materials and engage with support staff to enact reasonable adjustments. Attitudes towards perceived equity and fairness were also raised, where Walsh (Reference Walsh2012), for example, stated that teachers were reluctant to put extra effort into the needs of one child over the class. Pearce, Campbell-Evans, and Gray (Reference Pearce, Campbell-Evans and Gray2010) and Pedersen et al. (Reference Pedersen, Cooley and Rottier2014) also reported teacher ambivalence toward adjustments in that if teachers did not believe that a student should have reasonable adjustments to facilitate their inclusion, it was not going to happen. Petriwskyj (Reference Petriwskyj2010) describes how one teacher stated that they were not trained in special education and so students with disability were not their responsibility. Conversely, supportive teachers were found to be paramount to the successful implementation of reasonable adjustments. Generally, positive attitudes have been found in younger female teaching staff compared with teachers who are older and male. Further, student teachers have the most positive attitudes toward implementing inclusive practices (Vaz et al., Reference Vaz, Wilson, Falkmer, Sim, Scott, Cordier and Falkmer2015).

Flexibility of reasonable adjustment approaches required

How and when teachers used resources needed to consider the classroom environment where one reasonable adjustments approach that meets one student’s needs may not meet another. As an example, some students do not like being perceived as different and are reluctant to use accommodations such as laptops, a reasonable adjustment a teacher may have had success with previously, but it is now not appropriate in terms of another student’s social needs and identity considerations (Murchland & Parkyn, Reference Murchland and Parkyn2010). Several authors echo this finding, stating that no two students are alike, and flexibility in practice is crucial (Datta & Palmer, Reference Datta and Palmer2015; Saggers, Reference Saggers2015).

Professional competence

Dickson (Reference Dickson2012) argues that legislation is not the key concern for the successful implementation of reasonable adjustments, but instead, teacher professional competence is. Pearce, Campbell-Evans, and Gray (Reference Pearce, Campbell-Evans and Gray2010) however, regard the lack of professional competence as an excuse used to avoid addressing student individual needs. Petriwskyj (Reference Petriwskyj2010) commented that one teacher noted there was limited access to professional development, and it was only provided when there was a special request made or when a crisis unfolded. The need for professional development, however, was made clear by Glover et al. (Reference Glover, McCormack and Smith-Tamaray2015), who highlighted the concern made by teachers themselves regarding the need for additional professional development. Saggers (Reference Saggers2015), Duncan and Punch (Reference Duncan and Punch2021), and Duncan et al. (Reference Duncan, Punch and Croce2021) also commented on the critical need to upskill teachers in this area. Ho et al. (Reference Ho, Stephenson and Carter2017) reported on the relationship between formal training and increased use of reasonable adjustments in mainstream classrooms. Additionally, tools to assist in the identification of reasonable adjustments have been identified as a valuable addition to professional development for teachers that assists in avoiding gaps and fragmentation when applying reasonable adjustments (Davies et al., Reference Davies, Elliott and Cumming2016; Evans, Reference Evans2007).

The lack of competency among teachers was associated with a lack of confidence in applying reasonable adjustments (Pedersen et al., Reference Pedersen, Cooley and Rottier2014; Petriwskyj, Reference Petriwskyj2010) and a perceived inability to meet the needs of a child with disability in mainstream classes (Davies et al., Reference Davies, Elliott and Cumming2016).

Access to resources

There were consistent reports critical of the level of resource provision to support effective implementation of reasonable adjustments (Duncan & Punch, Reference Duncan and Punch2021; Duncan et al., Reference Duncan, Punch and Croce2021; Petriwskyj, Reference Petriwskyj2010; Walsh, Reference Walsh2012). Of note, Stephenson et al. (Reference Stephenson, Browne, Carter, Clark, Costley, Martin, Williams, Bruck, Davies and Sweller2021) found that parents were more likely than teachers to be concerned with a lack of funding and resources.

Influence of Support Staff

Role of teacher aides

Teachers, in general, were shown to rely on teacher aide support to implement any reasonable adjustment. Butt (Reference Butt2016) stated, however, that teacher aides do not have clear role descriptions and so are unsure about what they are required to do. Gibson et al. (Reference Gibson, Paatsch and Toe2016) also found that there are inconsistent expectations at the intersection of teacher and teacher aide roles in mainstream classrooms. Pedersen et al. (Reference Pedersen, Cooley and Rottier2014) also noted that if teacher aides were not present in class, teachers tended to exclude students with disability from the group. Conversely, the presence of teacher aides facilitated learning for the student with disability (Barr & Mavropoulou, Reference Barr and Mavropoulou2021).

Professional competence of teacher aides

Given the importance of the role that teacher aides play to support learning in mainstream classrooms, it is unsurprising that teachers reported the need for professional development of teacher aide staff (Pearce, Campbell-Evans, & Gray, Reference Pearce, Campbell-Evans and Gray2010; Tait & Hussain, Reference Tait and Hussain2017). Butt (Reference Butt2016) reported that teacher aides did not possess suitable qualifications to be able to effectively perform their tasks, which in turn will be problematic for the implementation of administering reasonable adjustments.

Communication Between School, Parents, and Student

Collaborative practices were regarded as playing a very important role in successful reasonable adjustment implementation. Collaboration and communication, if absent, created frustration with issues of funding, personnel, and resources (Glover et al., Reference Glover, McCormack and Smith-Tamaray2015). Moreover, when effective communication was present, it occurred regularly and involved all stakeholders. Consultation with the whole school and community was regarded as essential for teachers to overcome feelings of isolation and increase the likelihood of successful implementation of reasonable adjustments. Effective communication between home and school also facilitated positive student learning outcomes (Reupert et al., Reference Reupert, Deppeler and Sharma2015; Round et al., Reference Round, Subban and Sharma2016; Stephenson et al., Reference Stephenson, Browne, Carter, Clark, Costley, Martin, Williams, Bruck, Davies and Sweller2021). Cumming et al. (Reference Cumming, Dickson and Webster2013) also highlighted the importance of consultation with students, particularly at the secondary school level, especially when high-stakes academic assessment is relevant (Cumming & Dickson, Reference Cumming and Dickson2007).

Discussion

The scoping review presented in this article sought to respond to the following question: What are the enablers and barriers for teacher practice in making reasonable adjustments in mainstream primary and secondary school classrooms in Australia? Results from the 25 included studies identified five main themes to be considered in the successful provision of reasonable adjustments within Australian mainstream schools. These include

issues relating to legislative systems,

considerations regarding the school environment,

factors relating to the classroom environment,

understanding the importance of support staff, and

recognising the significance of effective communication between all stakeholders including the crucial role support staff play.

The results outlined in the previous section concentrate on the key elements requiring consideration for successful reasonable adjustments to be implemented. The application of reasonable adjustments need not be served as a legislative obligation, however, but as a common-sense modification that enables students to more effectively access their education. Therefore, we provide a model of best practice for educators that might be followed (Figure 3) that speaks to the relationships between the findings and suggests a direction for further investigation. It is intended that this model can also be harnessed in the context of teacher education to inform future practice in a more evidence-informed manner.

Figure 3. Model Presenting the Influential Factors for Making Reasonable Adjustments for Students With Disability in Australian Mainstream Classrooms.

Overall, our model depicts the influential factors affecting the implementation of reasonable adjustments in Australian educational contexts. Initially, legislation (including funding and policy) influences the general school environment, determining school funding and shaping governance at this level. The school context, in particular the school leadership, then determines where and how the funding is distributed, which in turn directly influences access to professional learning and the subsequent classroom environment. Elements of the classroom context and resourcing, such as teacher aides and teacher aide competency, teacher attitudes and teaching flexibility, interact to create a classroom environment that directly affects communication between stakeholders, not limited to teachers, parents and caregivers, and students. Thus, when examining the enablers and barriers to reasonable adjustment provision within mainstream school settings in Australia, there are multiple levels and interactions to be considered. It is too basic to simply state ‘Teachers need more time’ or ‘Teachers require more professional learning’ as an effective ‘fix’ for enhancing and increasing the use of reasonable adjustments in classrooms, as this does not consider the complex nature of the legislation, leadership, and school context, all of which play significant roles in constraining or liberating classroom inclusivity.

As seen in our model, legislation and individual school environment variables determine the funding available to support the infrastructure of reasonable adjustments. In this way, schools can determine where and how funds are distributed and utilised within their school. In some circumstances, this could be an opportunity for schools to make decisions based on the specific needs of their students in unique ways. However, our results largely showcase the barriers to implementing reasonable adjustments within the Australian educational context based on these factors. A negative feedback loop can be interpreted from the results whereby teachers report feeling unsupported in implementing reasonable adjustments, which may impact upon the development of negative feelings toward teaching students with disability and designing and implementing reasonable adjustments, which in turn impacts upon parent/caregiver decisions to remove students from mainstream classrooms where they feel their child is being unsupported. This then leads to schools receiving less funding for students with disability, which then feeds back into teachers feeling less supported by their schools in terms of providing for students with disability. The recent rapid growth in the number of support classes in the New South Wales public education jurisdiction would appear a demonstrable, and troubling, outcome of this paradigm. Across the state there are now more than 1,860 support classes, with more planned.

This feedback loop also highlights the association between negative classroom experience for students with disability and the lack of preparedness mainstream teachers feel when required to teach a range of students who present with diverse learning needs (Dally et al., Reference Dally, Dempsey, Ralston, Foggett, Duncan, Strnadova, Chambers, Paterson and Sharma2019; Duncan & Punch, Reference Duncan and Punch2021; Duncan et al., Reference Duncan, Punch and Croce2021; Forlin et al., Reference Forlin, Sin and Maclean2013), whereby teachers report low confidence and low satisfaction when teaching students with disability (Vermeulen et al., Reference Vermeulen, Denessen and Knoors2012). It is not a lack of teacher desire that presents as the issue; rather, it is experience, training, funding, plus, more broadly, truly embedding a culture of inclusivity within the framework of a school’s improvement processes.

As the distribution of funding is determined on an individual basis by schools, it leads to the issue of how schools determine exactly what a reasonable adjustment is (i.e., what is deemed as ‘reasonable’). As noted, schools are not required to implement an adjustment if it is seen as unreasonable or if compliance would impose hardship on the school if, for example, the required reasonable adjustments would incur high costs. Therefore, a major barrier to the implementation of effective reasonable adjustments within schools in Australia is the lack of guidelines to assist schools in determining a reasonable adjustment (Duncan et al., Reference Duncan, Punch, Gauntlett and Talbot-Stokes2020; Poed & Keen, Reference Poed, Keen, Garrick, Poed and Skinner2009).

Limitations and Future Research

This scoping review was limited to peer-reviewed articles investigating reasonable adjustments in Australia. A scoping review that examines similar constructs in other countries may prove informative. Similarly, this scoping review was also limited to peer-reviewed journal articles. Analysis of grey literature may add to the findings.

Conclusion

Inclusive education in the Australian context (in policy and definition, in the advocacy of placement and in classroom practice) is contentious in that there is little consensus in clearly defining policy with subsequent practice. Boyle and Anderson (Reference Boyle, Anderson, Sharma and Salend2020) liken the progress of the inclusive education journey to a bike with no momentum, where eventually the bike will fall over. We propose, therefore, a model of practice that will enable the forward momentum of the practice of reasonable adjustments within mainstream educational settings that will maximise outcomes for all students. All students have the right to an education. To facilitate this right for students with disability, reasonable adjustments are required. However, application of reasonable adjustments can be complex. Researchers and educators are encouraged to collaborate to better understand how to conduct additional research with the goal to better implement educational adjustments for students with disability.