Inclusive education is widely considered as the most preferred form of education for students with special educational needs (SEN) around the world. One of the arguments for implementing inclusive educational policies concerns the social benefits that students with SEN gain through their interaction with their peers. However, such benefits might not always be achieved since students with SEN are often found to face significant difficulties in their interactions with peers (Bossaert et al., Reference Bossaert, Colpin, Pijl and Petry2013).

In their attempt to synthesise the research studies on the social outcomes of inclusion in primary settings, Koster et al. (Reference Koster, Nakken, Pijl and van Houten2009) concluded that the term ‘social participation’ is the most suitable one to capture the fullness of the social aspects of inclusion. According to these authors, this multidimensional construct consists of four key themes: (a) the presence of social contacts/interactions, (b) acceptance by others, (c) social relationships, and (d) self-perception of acceptance by classmates. In a more recent review of similar research conducted in secondary settings, Bossaert et al. (Reference Bossaert, Colpin, Pijl and Petry2013) developed this framework further by revising the fourth dimension to reflect the students’ self-perceptions of social interaction. Considering the outcomes of these reviews, one could argue that the social participation of students with SEN in regular education settings is far from a straightforward process. Indeed, several recent studies in the field have found students with SEN experiencing a greater risk of being socially marginalised within their class than their classmates (Bossaert, de Boer, et al., Reference Bossaert, de Boer, Frostad, Pijl and Petry2015; Koster et al., Reference Koster, Pijl, Nakken and Van Houten2010; Schwab, Reference Schwab2015). On the other hand, despite their well-documented poor social participation, students with SEN often do manage to form some relationships and become members of peer groups (Frostad & Pijl, Reference Frostad and Pijl2007). Consequently, there is a need to shift the research focus from the sole measurement of social participation to the examination of the quality of the students’ best friendship. ‘Friendship quality’ represents a complex concept consisting of multiple dimensions. Despite differences between theoretical models in the psychological literature, there seems to be ample consensus about the importance of the dimensions of support, intimacy, and conflict. High-quality friendships are therefore based on mutual support, trust and the swift resolution of any conflict that might arise (Bukowski et al., Reference Bukowski, Hoza and Boivin1994).

The Social Participation of Students With SEN

Regarding the key theme of social interactions, students with SEN are more often recorded to be alone in the playground and have fewer interactions during break time with their peers than their classmates without SEN (Koster et al., Reference Koster, Pijl, Nakken and Van Houten2010; Schwab, Reference Schwab2015). Alarmingly, the literature clearly shows that this lack of interaction between students with SEN and their peers is due to significantly fewer attempts not only from the students with SEN but also from their peers (Avramidis et al., Reference Avramidis, Avgeri and Strogilos2018).

Regarding social acceptance by classmates, the literature shows that students with SEN are less accepted and more rejected than their typically developing (TD) peers (Bossaert, de Boer, et al., Reference Bossaert, de Boer, Frostad, Pijl and Petry2015; Pijl & Frostad, Reference Pijl and Frostad2010; Schwab, Reference Schwab2015). Moreover, the few longitudinal studies in the field suggest that the poor social acceptance students with SEN experience within their class network deteriorates over the course of a school year. For example, in Kuhne and Wiener’s (Reference Kuhne and Wiener2000) study of 9- to 12-year-old students, those children with learning difficulties who were found to possess ‘average’ social status at the beginning of the school year were more likely than their TD peers to change their status to ‘neglected’ or ‘rejected’ at the end of the year. Similarly, Frederickson and Furnham (Reference Frederickson and Furnham2001) investigated the longitudinal stability of sociometric classification in students with moderate learning difficulties (MLD) aged 8 to 10 years in an English county over a 2-year period. They found that students with MLD on both occasions were less likely to be classified as ‘popular’ and more likely to be classified as ‘rejected’. More importantly, their sociometric status remained fairly stable over the 2-year period.

Regarding friendships, the literature shows that students with SEN have fewer friends in their class than their classmates without SEN (Frostad & Pijl, Reference Frostad and Pijl2007; Koster et al., Reference Koster, Pijl, Nakken and Van Houten2010; Schwab, Reference Schwab2015). Moreover, even when students with SEN manage to establish some friendships, these seem to be of low quality (Wiener & Schneider, Reference Wiener and Schneider2002) and, more worryingly, they tend to be less stable (Frostad et al., Reference Frostad, Mjaavatn and Pijl2011; Schwab, Reference Schwab2019).

Regarding the students’ social self-concept, the evidence from previous studies is inconsistent. Considering early studies in the field that had included a measure of social self-concept, Pijl and Frostad (Reference Pijl and Frostad2010) concluded that students with learning disabilities held lower perceptions than their TD peers. Other more recent studies, however, failed to detect such a difference (Avramidis et al., Reference Avramidis, Avgeri and Strogilos2018; Koster et al., Reference Koster, Pijl, Nakken and Van Houten2010).

The Friendship Quality of Students With SEN

The findings on the quality of the friendships students with SEN develop are rather mixed. Specifically, the friendships of students with learning difficulties tend to be characterised by less frequent contact, less intimacy, less validation, and more conflicts than the ones reported by their TD peers (Wiener & Schneider, Reference Wiener and Schneider2002). Additionally, Lee et al. (Reference Lee, Yoo and Bak2003) concluded that students with mild learning disabilities tend to establish less equal friendships with their TD peers, and the latter usually act as leaders by adopting a caring and protective role. By contrast, moderately positive results are reported in more recent studies. Webster and Carter (Reference Webster and Carter2013), for example, found no differences between the perceptions of friendship quality held by students with developmental (mainly intellectual) disabilities and the perceptions held by their classmates without SEN in inclusive educational settings. In this study, the target students engaged in common activities and experienced reciprocal liking and enjoyment with their TD friends. Further, their closest relationships demonstrated most of the dimensions of a high-quality friendship, such as companionship, validation, care, help, and conflict resolution. Nevertheless, evidence of more intimate relationships was limited as the friendship dyads examined in this study reported infrequent engagement in behaviours, such as sharing of intimate information and going to each other’s houses. Similar results were reported in another study by Bossaert, Colpin, et al. (Reference Bossaert, Colpin, Pijl and Petry2015), which examined the dimensions of companionship, intimacy and support of reciprocated friendships of students with autism, students with motor and/or sensory disabilities, and students without SEN at the start of mainstream secondary school. Specifically, they found no differences between ‘companionship’ and ‘support’ in the reciprocated friendships of the three groups. In line with the Webster and Carter (Reference Webster and Carter2013) study, students with autism reported significantly less intimacy in their friendships than did TD students.

Finally, the literature includes two studies that reported positive results with regard to the friendship quality of students with learning difficulties (Avramidis et al., Reference Avramidis, Avgeri and Strogilos2018; Hoffmann et al., Reference Hoffmann, Wilbert, Lehofer and Schwab2021). In the first study by Avramidis et al. (Reference Avramidis, Avgeri and Strogilos2018), the students with MLD had fewer friends and fewer social interactions with peers; however, at the same time, these students possessed a positive social self-concept and scored very highly on all assessed dimensions of friendship quality. Likewise, in the second study by Hoffmann et al. (Reference Hoffmann, Wilbert, Lehofer and Schwab2021), the perceptions of students with learning difficulties about the quality of their friendships did not differ from those reported by their classmates.

Linking Social Functioning With Socio-Emotional Skills

The difficulties students with SEN experience in their social interaction with peers and subsequent bonding might reflect their own insufficient sets of age-group-appropriate social skills (Frostad & Pijl, Reference Frostad and Pijl2007). As Garrote (Reference Garrote2017) pointed out, socially competent children can engage in social interactions in order to satisfy their goals and needs while considering the needs and goals of others. Garrote goes on to distinguish between ‘self-oriented’ and ‘other-oriented’ social skills. The first are important for the self since they enable the individual to successfully interact and bond with peers and include skills such as leadership, assertion, and self-control. Other-oriented skills such as helping, caring, cooperating and showing empathy are equally important because they enable the individual to take into consideration interests and benefits of others in social interactions.

Notwithstanding the importance of socio-emotional skills in the students’ social development, the evidence surrounding their impact on the social participation of students with SEN is rather mixed. For example, Frostad and Pijl (Reference Frostad and Pijl2007) found a weak relationship between the perceived social skills of students with learning difficulties (cooperation and empathy) and their social position in regular classes. However, in the same study, a stronger relationship was detected in students with behavioural difficulties. Similarly, Schwab et al. (Reference Schwab, Gebhardt, Krammer and Gasteiger-Klicpera2015) found that the low levels of prosocial behaviour displayed by students with SEN along with indirect forms of aggression were predictors of the social difficulties experienced by these students. By contrast, Garrote (Reference Garrote2017) failed to find a significant relationship between the social skills and social participation of students with intellectual disabilities, despite the latter having significantly lower levels of social skills compared to their peers without SEN.

Objectives of the Study

The current study differs from previous social participation studies in terms of including an additional measurement of best-friendship quality, a variable that has been overlooked in most research efforts to date. Moreover, given that most existing research has described static situations, we considered it necessary to conduct a longitudinal research study to examine the stability of the variables measured. Accordingly, the present study examined the social participation of students with MLD in regular secondary schools and their perceptions of best-friendship quality at Grade 7 (T1) and 2 years later at Grade 9 (T2).

The study pursued the following research aims:

-

To ascertain the social participation students with MLD experienced within their class network (both at T1 and T2)

-

To examine the perceptions of students with MLD about the quality of their best friendship (both at T1 and T2)

-

To investigate the perceptions of students with MLD about their socio-emotional skills and their association with social participation and friendship quality dimensions (T2 only).

Based on former studies (e.g., Bossaert, de Boer, et al., Reference Bossaert, de Boer, Frostad, Pijl and Petry2015; Koster et al., Reference Koster, Pijl, Nakken and Van Houten2010; Schwab, Reference Schwab2015), we expected to find at both assessment points that students with MLD experience lower social participation than their TD classmates. Moreover, in the light of the inconsistent picture emerging from the literature review (e.g., Avramidis et al., Reference Avramidis, Avgeri and Strogilos2018; Bossaert, Colpin, et al., Reference Bossaert, Colpin, Pijl and Petry2015; Hoffmann et al., Reference Hoffmann, Wilbert, Lehofer and Schwab2021), we expected that the students with MLD’s perceptions of friendship quality would not be significantly different from those held by their classmates. Further, on the basis of previous research (e.g., Frostad & Pijl, Reference Frostad and Pijl2007; Schwab et al., Reference Schwab, Gebhardt, Krammer and Gasteiger-Klicpera2015), we anticipated that the students with MLD’s perceptions of their socio-emotional skills would be poorer compared to those held by their peers. Lastly, we anticipated detecting associations between socio-emotional skills and the social participation and friendship quality dimensions measured.

Methodology

The study represents a longitudinal research design. At both assessment points, the peer nomination sociometric technique was combined with systematic observations and self-report psychometric instruments.

Participants

Participants were drawn from five general secondary schools in a central region of Greece. All students registered at 15 Grade 7 classes were invited to participate in the study at T1 and 2 years later at Grade 9 (T2). Only students who completed the questionnaires at both assessment points and who provided their written consent to participate in addition to their parents’ consent were included in the analyses presented in this paper. Of the 330 students who were invited to participate in T1, seven students were either absent (e.g., because of illness) or declined to participate for other reasons (e.g., parental consent was not granted). In addition, 10 further students did not participate in T2 because they moved to a different school. The final sample consisted of 313 students with a mean age of 12.8 years at T1 and 14.8 years at T2. Approximately 15% (N = 46) of these students (36 boys and 10 girls) experienced MLD, whereas the remaining 267 students (135 boys and 132 girls) did not experience learning difficulties or any other type of disability.

It is worth noting that the term MLD is used in this study as a synonym for the term ‘learning disabilities’, a concept that is not clearly understood in its definition and in its general use. As Grünke and Cavendish (Reference Grünke and Cavendish2016) point out,

understanding of the term [learning disabilities] ranges from viewing it as a disorder that is characterized by at least average intelligence with isolated developmental delays in very specific areas (like reading, spelling, or arithmetic) to a condition that is basically identical with what is commonly known as mild mental retardation. (p. 2)

With regard to identification, in some countries including Greece, children are identified as experiencing MLD on the basis of their poor school attainment; in others (e.g., the United States [US]), their identification is based on their intellectual functioning as measured by cognitive ability (i.e., IQ) tests (Norwich et al., Reference Norwich, Ylonen and Gwernan-Jones2014). Consequently, in Greece, students labelled as having MLD typically experience difficulties in their academic performance despite the availability of learning support either in class or outside the class in resource rooms. Moreover, in the Greek context, these difficulties are in most cases accompanied by various types of behavioural difficulties such as disruptive overt behaviour and/or internalised emotional difficulties. All students with MLD participating in the present study had also been diagnosed by educational psychologists in public diagnostic centres as experiencing MLD and received additional within-class support by special education teachers.

Methods

Assessment of peer acceptance and friendships

Peer acceptance was assessed through the peer nomination technique, which required students to name up to five classmates they regarded as friends. Peer acceptance was defined as the number of nominations each student had received from their classmates, and friendship was defined as a reciprocated nomination between two students.

Assessment of contacts/interactions

The number of successful interactions students initiate or receive in the playground was recorded through an observation scheme consisting of five discrete categories: (a) target student initiating interaction with peer, (b) target student receiving interaction with peer, (c) target student initiating interaction with teacher, (d) target student receiving interaction with teacher, and (e) target student being alone. Students were observed for 15 minutes in total, representing three different 5-minute periods. Every period was divided into 30 intervals of 10 seconds, resulting in observation scores ranging from 0 to 90.

Assessment of social self-perception

The social self-concept subscale of the Self-Description Questionnaire I developed by Marsh (Reference Marsh1990) was used to elicit the participating students’ perceptions. This is a Likert scale consisting of eight items such as ‘I have many friends’, ‘Most kids like me’, etc. Students had to respond by choosing one of the following options: false (1), mostly false (2), sometimes false/sometimes true (3), mostly true (4), or true (5). In the current study, this scale showed good reliability on both administrations, as evaluated by the Cronbach’s alpha coefficient (a = .83 and a = .86, respectively).

Assessment of friendship quality

Students were asked to name only one peer as their best friend and mention whether that child was a classmate or not. The quality of the nominated best friendship was subsequently rated through the completion of the Friendship Qualities Scale, a self-report instrument developed by Bukowski et al. (Reference Bukowski, Hoza and Boivin1994). This instrument contains 23 items that represent the following five dimensions of friendship quality: companionship (four items; e.g., ‘My friend and I often do fun things together’), conflict (four items; e.g., ‘My friend and I disagree about many things’), help (five items; e.g., ‘My friend helps me when I have trouble with something’), security (five items; e.g., ‘If there is something bothering me, I can tell my friend about it’) and closeness (five items; e.g., ‘I feel happy when I am with my friend’). These items could be answered on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (5). In the present study, the internal consistency of the five friendship dimensions was satisfactory on both administrations, with Cronbach alphas ranging from .74 to .80 at T1 and from .80 to .86 at T2.

Assessment of socio-emotional skills

The students’ socio-emotional skills were assessed at T2 through the administration of a reduced version of a Psycho-Social Adaptation Scale developed and standardised in the Greek context by Hatzichristou et al. (Reference Hatzichristou, Polychroni, Bezevegis and Mylonas2011). This version consists of 25 items that represent two social skills (‘Assertion’ and ‘Co-operation’) and two emotional skills (‘Self-control’ and ‘Empathy’). Indicative examples of these skills are ‘Whenever I have a problem, I ask for help’ (assertion), ‘I work with my classmates in group activities’ (cooperation), ‘I can control my anger’ (self-control), and ‘I can tell when one of my friends is sad’ (empathy). To complete this instrument, students had to choose among the following options: false (1), mostly false (2), sometimes false/sometimes true (3), mostly true (4), or true (5). In the current study, the internal consistency of the four socio-emotional skills’ dimensions was satisfactory, with Cronbach’s alphas ranging from .75 to .80.

Procedures

Before data collection, we received ethical approval from the Ministry of Education (Protocol Number: 50176/Δ3), and all the participating students and students’ parents signed consent forms.

Data collection was carried out in March 2016 (T1 – towards the end of Grade 7) and in March 2018 (T2 – towards the end of Grade 9). The instruments were administered during structured lessons and completion typically required 30 minutes. On some occasions, specific adaptations were made, such as reading aloud the items to enable some low-attaining readers to participate. Systematic observations of the interactions of all 46 students with MLD were conducted in the schoolyard during recess by the first and second author. For the purpose of comparison, 46 students without learning difficulties or other disabilities were also observed; these students were of the same gender and had been randomly drawn from the same classes as the students with MLD. Observations on one quarter (n = 23) of all targeted students were conducted by the first two authors. Given that the interrater reliability was 90%, the remaining observations were conducted by the second author only.

Data Analysis

Since there was substantial variability in the size of the participating classrooms, the nominations’ data were transformed using a mathematical formula formerly utilised by Schwab (Reference Schwab2015) that allows relating a student’s peer acceptance to the mean peer acceptance of all students in the class:

The number of reciprocal choices made by students represented their established friendships within their class network. Following the computation of composite scores representing the students’ social self-concept, the five dimensions of friendship quality, and the four dimensions of socio-emotional skills, a series of comparisons were carried out between students with MLD and their peers without MLD. Likewise, a comparison of the frequencies of interactions during the observations between the two groups was conducted. The stability of the above measures over the 2-year period was also statistically examined. Comparisons by gender were also conducted for the MLD group only to detect statistically significant differences at both assessment points. Finally, correlational analyses were performed to detect associations between socio-emotional skills and the students’ perceptions of social self-concept and best-friendship quality.

Results

Social Participation

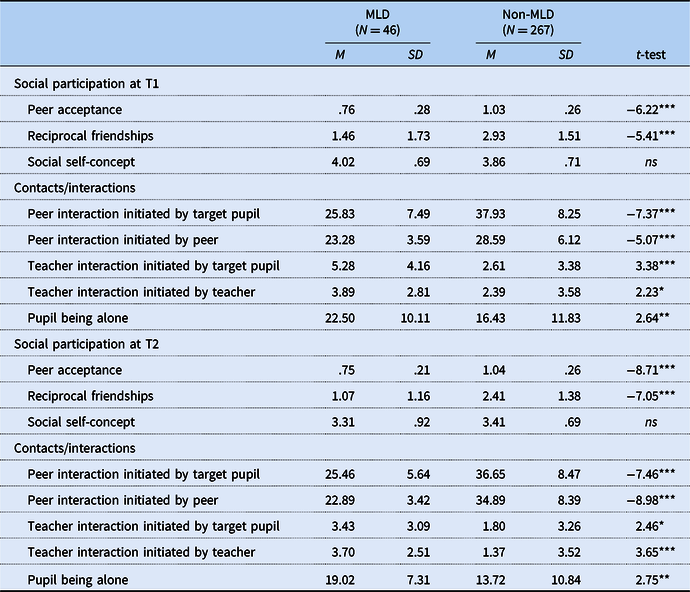

As it can be seen in the top panel of Table 1, the students with MLD experienced lower peer acceptance and had fewer friends than their peers without MLD at T1. On both accounts, the difference was statistically significant (t = −6.22, p < .001 and t = −5.41, p < .001). Interestingly, the two groups did not differ in their perceptions of social self-concept, which were very positive.

Table 1. Social Participation of Students With and Without Moderate Learning Difficulties (MLD) at T1 and T2

*p < .05. **p < .01. ***p < .001.

The analysis of the observational data revealed that the students with MLD had fewer interactions with peers in the playground than their counterparts without MLD. This finding was true for both interactions initiated by the students with MLD and for those initiated by their peers. An opposite trend was detected with regard to the student–teacher interactions, since students with MLD were observed to interact more often with their teachers irrespective of who started the interaction. Finally, the students with MLD were more often recorded to be alone than their peers without MLD.

The statistical analyses conducted at T2 produced similar results to T1 with regard to peer acceptance, number of friendships and social self-concept. The bottom panel of Table 1 reveals that the students with MLD at Grade 9 experienced lower peer acceptance and had fewer friendships than their classmates without MLD (t = −8.71, p < .001 and t = −7.05, p < .001, respectively). Again, both groups held positive perceptions of social self-concept. Similar findings to T1 were reached by the statistical analyses concerning the two groups’ interactions with peers and teachers, and the number of instances being alone.

To examine the stability of all social participation dimensions over the 2-year period, we conducted a series of 2 (time) x 2 (MLD/TD) repeated measures ANOVAs. None of the analyses detected a statistically significant difference between the two assessment points, indicating that peer acceptance, reciprocal friendships, perceptions of social self-concept, and levels of interactions remained stable. Nonparametric comparisons (Mann–Whitney tests) between boys and girls with MLD were also conducted to examine differences in all social participation dimensions due to the small numbers involved (36 boys and 10 girls). The analyses failed to detect any statistically significant differences between the two groups at both assessment points.

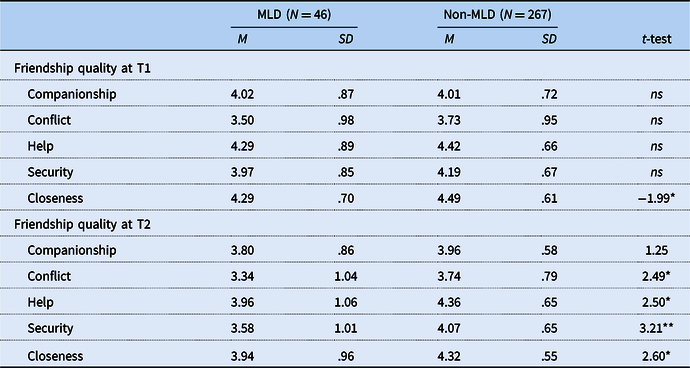

Friendship Quality

Examination of ‘reciprocity’ and shared perceptions of friendship quality was not possible given that the majority of the participating students with MLD indicated as a best friend a peer outside their class (65% of MLD students at T1 and 72% of MLD students at T2, whereas the corresponding figures for TD students were 18% and 44%, respectively). The analyses performed at T1 failed to detect statistically significant differences between the perceptions held by the two groups in relation to the dimensions of ‘companionship’, ‘conflict’, ‘help’, and ‘security’. The only statistically significant difference detected concerned the dimension of ‘closeness’ where students with MLD held lower, but still positive, perceptions than their counterparts without MLD.

The comparisons conducted at T2 revealed statistically significant differences between the two groups on all dimensions of friendship quality except the ‘companionship’ one. On all other accounts, the perceptions held by the students with MLD were lower compared to the corresponding ones of their peers without MLD; nevertheless, they were well above the average and, therefore, could be classified as fairly positive (see bottom panel of Table 2).

Table 2. Friendship Quality of Students With and Without Moderate Learning Difficulties (MLD) at T1 and T2

*p < .05. **p < .01.

To examine the stability of friendship quality dimensions over the 2-year period, we conducted five 2 (time) x 2 (MLD/TD) repeated measures ANOVAs. None of the analyses detected a statistically significant difference between the two assessment points. Again, no statistically significant differences were detected between boys and girls with MLD in all friendship quality dimensions at both assessment points.

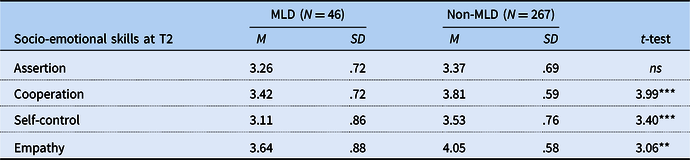

Socio-Emotional Skills and Their Association With Perceptions of Social Self-Concept and Friendship Quality

The analysis of the socio-emotional skills’ data revealed that students with MLD viewed themselves as less cooperative (t = 3.99, p < .001), having lower self-control (t = 3.40, p < .001) and lower empathy towards the others (t = 3.06, p < .01) than their peers without MLD. No difference was found in the two groups’ perceptions of assertive behaviour (see Table 3). Again, the comparisons by gender for the MLD group revealed no differences between the two groups in all four socio-emotional skills.

Table 3. Socio-Emotional Skills of Students With and Without Moderate Learning Difficulties (MLD) at T2

**p < .01. ***p < .001.

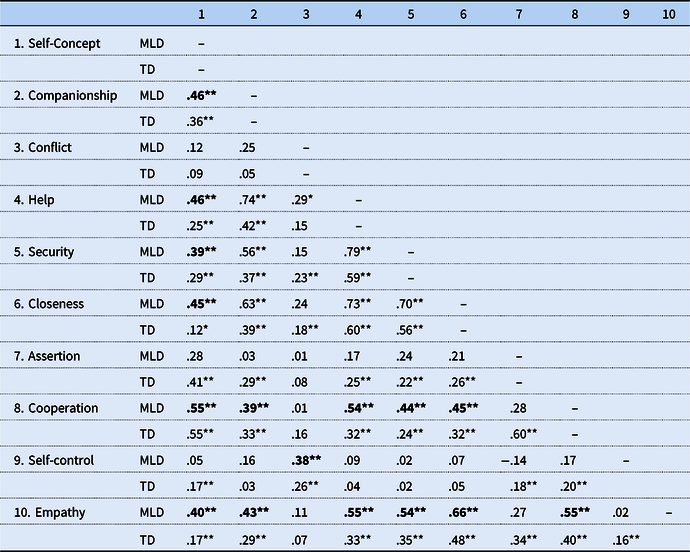

Next, the analysis examined possible associations between the students’ perceptions of socio-emotional skills and all dimensions of social participation and friendship quality measured. Socio-emotional skills were not related to peer acceptance, number of friendships, and frequency of social interactions. By contrast, socio-emotional skills were related to the students’ social self-concept and dimensions of friendship quality.

First, for the MLD group, positive correlations were found between the socio-emotional skills of ‘cooperation’ and ‘empathy’ and the social self-concept. Interestingly, the socio-emotional skills of ‘assertion’ and ‘self-control’ were not associated with the self-concept of the MLD group. By contrast, when examining the same correlations for the group without MLD, all socio-emotional skills were found to be correlated with self-concept, with ‘cooperation’ being the most strongly associated one.

Further examination revealed some interesting associations between the students’ socio-emotional skills and friendship quality (see Table 4). Specifically, for the MLD group, the social skill of ‘assertion’ did not correlate with any dimension of friendship quality. By contrast, for the group without MLD, ‘assertion’ was weakly correlated with the dimensions of ‘companionship’, ‘help’, ‘security’, and ‘closeness’. Moreover, for the MLD group, the social skill of ‘cooperation’ was moderately correlated with all positive dimensions of friendship quality (correlation coefficients ranged from .39 to .54). The same was true, albeit to a lesser extent, for the group without MLD (with correlations ranging from .24 to .33). A similar pattern emerged regarding the correlation between the emotional skill of ‘empathy’ and all the positive dimensions of friendship quality; for the MLD group, moderate to strong positive correlations (ranging from .43 to .66) were detected, whereas for the group without MLD these correlations were weaker (ranging from .29 to .48). Lastly, for the MLD group, the emotional skill of ‘self-control’ was moderately correlated (r = .38) with the negative dimension of ‘conflict’. Given that the items of this friendship dimension had been recoded, this positive correlation suggests that the students with MLD who held high perceptions of self-control also reported fewer conflicts with their best friend. The same was true, but to a smaller extent, for the group without MLD (r = .26).

Table 4. Correlations Between Social Self-Concept, Dimensions of Friendship Quality and Socio-Emotional Skills for Students With and Without Moderate Learning Difficulties (MLD) at T2

Note. All correlations are nonparametric Spearman correlations. Correlations of interest that are discussed in the article are shown in bold. TD = typically developing.

*p < .05. **p < .01.

Finally, as it can be seen in the first column of Table 4, the social self-concept of the students with MLD is positively associated with the dimensions of ‘companionship’ (r = .46), ‘help’ (r = .46), ‘security’ (r = .39), and ‘closeness’ (r = .45). These moderate correlations indicate that the presence of a high-quality friendship is associated with a positive perception of social self-concept. Similar positive correlations, albeit much lower, were detected for the students without MLD (ranging from .12 to .36).

Discussion

In the present study, the students with MLD held reduced peer acceptance, had fewer friendships, and engaged less often in social interaction with peers than their TD classmates on both administrations. These findings are in line with several recent studies in the field that found students with MLD having lower social participation in regular settings than their TD classmates (Bossaert, de Boer, et al., Reference Bossaert, de Boer, Frostad, Pijl and Petry2015; Koster et al., Reference Koster, Pijl, Nakken and Van Houten2010; Schwab, Reference Schwab2015). Moreover, the degree of peer acceptance experienced and the number of reciprocal friendships established by students with MLD were remarkably similar at the two assessment points. This finding is in agreement with the few available longitudinal studies reporting the stability of sociometric assessments in students with MLD (Frederickson & Furnham, Reference Frederickson and Furnham2001; Frostad et al., Reference Frostad, Mjaavatn and Pijl2011; Kuhne & Wiener, Reference Kuhne and Wiener2000; Schwab, Reference Schwab2019). In this respect, our study lends support to the claim that the social relations of students with MLD in regular schools remain fairly stable throughout their school careers.

Strikingly, the negative social standing of the students with MLD in this study did not translate into negative perceptions of social self-concept. Some authors (Koster et al., Reference Koster, Pijl, Nakken and Van Houten2010; Pijl & Frostad, Reference Pijl and Frostad2010) have argued that students with MLD often do not possess an accurate perception of their social situation, which might explain the discrepancy between the perceptions of social self-concept and actual peer acceptance recorded in this study. Another plausible explanation might be that the participating students with MLD had developed the ability to focus on the positive aspects of their peer relationships and not the negative ones (Avramidis et al., Reference Avramidis, Avgeri and Strogilos2018). A further explanation could be that secondary-aged students in Greece tend to engage in many out-of-school activities that offer them opportunities for social interaction and friendship development (e.g., almost all adolescents in Greece attend private foreign language classes in the afternoon and/or engage in artistic/sport activities). Indeed, in the present study, the majority of the participating students with MLD indicated as a best friend a peer from out-of-school contexts (e.g., neighbourhood, sports team, scout group). Conversely, the percentage of TD students naming a best friend from outside the school was much lower at both assessment points. Consequently, the positive perceptions of social self-concept reported by students with MLD suggest that having a close friend outside the school might be enough to counterbalance these students’ poor peer acceptance within their class network. This last explanation is further strengthened by the friendship quality analyses performed at both assessment points in which students with MLD held positive perceptions on all dimensions of friendship quality (Avramidis et al., Reference Avramidis, Avgeri and Strogilos2018; Bossaert, Colpin, et al., Reference Bossaert, Colpin, Pijl and Petry2015; Hoffmann et al., Reference Hoffmann, Wilbert, Lehofer and Schwab2021).

It is worth mentioning that the findings are context specific and reflect the sociocultural circumstances in which Greek adolescents find themselves. Given that friendship formation and the nature of established friendships are distinctly different across cultures, the findings reported here might not be replicated in other cultural contexts. For example, in their exploration of friendship formation in Indonesia and the US, French, Pidada, and Victor (Reference French, Pidada and Victor2005) demonstrated how cultural differences had affected the formation and the quality of the friendships established by adolescents in these two countries. The authors attributed the differences in friendship patterns detected to the ‘collectivist’ and ‘individualist’ cultures of Indonesia and the US, respectively. Although conducting such an analysis is beyond the scope of this paper, readers should be aware that Greece is a developed Western country representing a predominantly ‘individualist’ culture in which adolescents are afforded many opportunities for socialising with peers in out-of-school activities, including scouting, sports clubs, and music instruction. It is with this cultural context in mind that the findings reported here should be interpreted.

Another interesting finding of the present study concerns the perceptions that students with MLD held about their socio-emotional skills. Students with MLD viewed themselves as less cooperative, less capable of controlling themselves and of showing empathy towards the others than their TD peers. This result is in agreement with the meta-analysis of 152 studies conducted by Kavale and Forness (Reference Kavale and Forness1996), which concluded that 75% of the students with learning disabilities manifested social skill deficits that distinguished them from their TD counterparts. More recent studies have also found students with learning disabilities reporting lower levels of social skills (Frostad & Pijl, Reference Frostad and Pijl2007) and lower levels of prosocial behaviour (Schwab et al., Reference Schwab, Gebhardt, Krammer and Gasteiger-Klicpera2015) compared to their TD peers.

Strikingly, the socio-emotional skills assessed were not associated with the social standing of the students with MLD in their class network, as measured by their peer acceptance score. This finding is in line with Garrote’s (Reference Garrote2017) study, which failed to detect a significant correlation between peer acceptance and social skills. Specifically, Garrote found that pupils with intellectual disabilities were not less accepted if they had lower levels of teacher-rated social skills. Interestingly, in the present study the socio-emotional skills of ‘cooperation’ and ‘empathy’ were moderately associated with the students with MLD’s perceptions of social self-concept, indicating the link between these skills and these students’ views about their social standing.

Furthermore, in our study, the students’ perceptions of their socio-emotional skills were correlated with the five dimensions of friendship quality. Specifically, the skills of ‘cooperation’ and ‘empathy’ were associated with the positive dimensions of friendship quality, while ‘self-control’ was associated with the negative dimension of ‘conflict’. This finding reaffirms the contribution of these socio-emotional skills to becoming socially competent and, by extension, establishing high-quality friendships (Matson, Reference Matson2009).

Finally, an unexpected finding of this investigation concerns the identified moderate correlations between social self-concept and all positive dimensions of friendship quality. Although correlational analyses should always be treated with caution, we contend that this finding provides a plausible explanation for the often-reported paradox of students with MLD experiencing low peer acceptance and, at the same time, reporting positive perceptions of social self-concept. Put simply, having one high-quality friendship might be more important for developing a positive social self-concept than experiencing high peer acceptance by classmates. However, in the absence of any relevant studies in the field, more research is needed to strengthen this assumption.

Some limitations of the current study should be mentioned. First, we focused exclusively on the perceptions held by students without contrasting these with other assessments provided by key informants, such as teachers and parents. Second, the systematic observations conducted resulted in a crude estimate of the frequency of social interactions occurring in the playground. However valuable such a measurement might be, the lack of any data about the nature of the recorded interactions renders our interpretations shaky. Third, the study assessed the quality of the students’ self-rated best friendship with individuals who were not necessarily members of their class. In so doing, examination of ‘reciprocity’ and shared perceptions of friendship was not possible. Fourth, specific self- and other-oriented skills were measured, whereas other studies might have adopted a broader range of social skills. Recognising these limitations, the present study has highlighted some important aspects of the students with MLD’s social functioning in regular schools, thus offering some directions for improving school practices.

Conclusion

The findings reported in this investigation lend support to the consistently made claim that students with MLD in regular classes have lower levels of social participation than their TD peers (Schwab, Reference Schwab2019). However, it is certainly positive that the participating students with MLD had managed to develop one good friendship (mainly outside their class), which they perceived as close and held positive perceptions of social self-concept. This raises the question as to whether having just one high-quality friendship is enough to ensure the student’s emotional wellbeing. Further, the opportunities to participate in social activities outside the school (e.g., sporting teams) provided to students with MLD in the Greek context can be seen as an alternative to their poor acceptance experienced within the class. It would seem plausible then that students with MLD gravitate towards peers with common interests in out-of-school spaces where high-quality friendships are possible, which is not the case in more structured, traditional classrooms.

The poor social participation of pupils with MLD within their classrooms has been attributed to their reduced social skills (Schwab et al., Reference Schwab, Gebhardt, Krammer and Gasteiger-Klicpera2015). However, a caveat needs pointing out here. Although it seems reasonable to assume that having poor social skills prevents students with MLD from interacting and forming relationships with classmates, it is important to note here that it is difficult to separate cause from effect. Having well-developed social skills and engaging in prosocial behaviour can assist students to become members of peer groups within their class and ultimately develop friendships. On the other hand, experiencing low levels of interaction with peers and having a few or no friends at all will result in students having an underdeveloped set of social skills (Frostad & Pijl, Reference Frostad and Pijl2007). Nevertheless, given that social skill deficits have become a defining characteristic of students with learning disabilities, implementing systematic social skill training (SST) programs in schools has been advocated as a necessary measure to assist these students’ social functioning and, ultimately, participation (Garrote, Reference Garrote2017). Unsurprisingly then, to promote more effective social functioning, several structured SST programs have been developed (see Kavale & Mostert, Reference Kavale and Mostert2004, for an appraisal of some widely used programs in the field).

Paradoxically, despite their popularity, SST programs are only minimally effective in teaching social skills to children with learning disabilities. For example, the few available meta-analyses (Beelmann et al., Reference Beelmann, Pfingsten and Lösel1994; Kavale & Mostert, Reference Kavale and Mostert2004) of studies examining the efficacy of SST programs for students with learning disabilities suggest that SST has produced rather weak effects on the social skills of these students and on their social standing in the class. Commenting on the limited empirical support for SST, Gresham et al. (Reference Gresham, Sugai and Horner2001) noted that SST interventions often take place in ‘contrived, restricted, and decontextualized’ (p. 340) settings such as resource rooms or other pull-out settings thus leading to poor maintenance and generalisation effects.

To sum up, although SST programs cannot be dismissed as an important adjunct intervention for specific individuals that stand out as marginalised such as students with MLD, we contend that implementing such programs in schools can be challenging for school personnel who are often presented with limited time, resources, and training. More importantly, there is a danger that traditional SST interventions might lead to some students’ stigmatisation. Instead, we would argue here, following Spence (Reference Spence2003), that SST interventions are most effective when they are implemented at the whole-school level and some key systemic factors, such as the whole-school ethos and staff and peer attitudes, are also altered. Furthermore, there is a need to shift the research focus from those individual students who stand out as marginalised towards implementing more promising interventions that involve all members of the class (see Garrote et al., Reference Garrote, Dessemontet and Opitz2017, for a review of school-based interventions). Such programs include activities aiming to increase understanding and acceptance of diversity, promote group bonding and ultimately create an inclusive community for all students. Additionally, various practices at the school level, such as the introduction of extracurricular activities (i.e., artistic and sports events) in the school curriculum, have great potential in improving peers’ relationships. The students’ socio-emotional development can also be supported indirectly through the implementation of innovative instructional approaches, especially those involving cooperative learning activities (e.g., peer tutoring), which can foster social interaction and the development of friendships (Bowman-Perrott et al., Reference Bowman-Perrott, Burke, Zhang and Zaini2014). Future research efforts could be directed towards evaluating structured programs as well as collaborative teaching arrangements of the types mentioned above.

Funding

This research is co-financed by Greece and the European Union (European Social Fund) through the operational program ‘Human Resources Development, Education and Lifelong Learning’ in the context of the project ‘Strengthening Human Resources Research Potential via Doctorate Research’, implemented by the State Scholarships Foundation (IKY).