This article is based on a doctoral dissertation that focused on the experiences of adult learners who returned to complete the requirements of a high school diploma in an adult high school learning space. Territorialized notions of the bodies that are supposed to be graduated/produced within school makes the decision to leave school nonsensible, and the bodies are marginalized from the norm. However, the invisible can have the potential for virtual creative power (Deleuze, Reference Deleuze1988; Means, Reference Means2011) that can be used to re-imagine things in society and education spaces. The dominant and linear views of less educated adults as lacking and incomplete can be transformed by deterritorializing the adult through the systematic liberation of desire (Deleuze, Lapoujade & Taormina, Reference Deleuze, Lapoujade and Taormina2004). Research around the high school dropout often lacks the complexity of the dropout story. In particular, very little attention has been afforded to the adult learner who returns to school (Berliner & Barrat, Reference Berliner and Barrat2009) because the common perception of the students who drops out of school is that the decision to drop out is permanent (Barrat, Berliner, & Fong, Reference Barrat, Berliner and Fong2012).

The purpose of this study was to (de)(re)territorialize the high school dropout found at the margins of an education system that operates within an assumed discourse of the ideal graduate. Although a review of the literature was derived from research around the dropout phenomenon, the focus for this research was on the affective events intra-related to the re-entry of the becoming adult participants.

As education systems strive to produce the ideal graduate, they also serve to exclude and discriminate against individuals who exits the system as ‘less than ideal’. As one’s legitimacy and visibility become lost in society, in some literature, this person remains stagnant, lacking, and virtually unrecognized (Backman, Reference Backman2017; Bowers & Spott, Reference Bowers and Spott2012; Campbell, Reference Campbell2015). The individual’s existence is insignificant. However, the significance and implications of mapping the assemblages of the participants’ lives may allow for the emergence of new ways to think about the insignificant body that lives on the fringes. Historical evidence found in various research exists to position the uneducated adult as a burden to society, incapable of living an independent and fulfilling life (Campbell, Reference Campbell2015). Yet, the researcher’s own intra-action with adults who return to complete their high school diplomas has served to provide a much different perception of these learners. The intra-relational/connectedness of bodying assemblages formed ‘in between’ events of dropping out and dropping in to high school provide an affective account of these adults’ journeys. The noninterpretive approach to the research allows the telling narrative of the participants to be read in their raw forms. Each reader of the research is affected in different ways each time the document is read. Deleuze’s theory of affect provides an excellent frame to think about these adult learners and education in various and differentiated ways (Means, Reference Means2011).

Wallin (Reference Wallin, Carlin and Wallin2014) suggested that the individual who drops out of school might be considered ‘one of contemporary education’s greatest political problems’ (p. 133) because of the image that is created. This image grates against ‘a well-adapted and homogenous and institutional subject’ (p. 133). The dropping out simply diverges from the image to which the system aspires. In the choice to resist integration, a new line of flight is being plotted that fulminates a (dis)(re)ruption in the system, and the person makes a move elsewhere. The individual (dis)identifies with formal education, and the newness that potentially can be created is found in ‘an open landscape of multiplicity’ (Aoki, Reference Aoki, Pinar and Irwin1993/2004, p. 207) where the nomadic process of becoming continues. Therefore, ‘the dropout is no longer thought of in pejorative terms, but, rather, as a potential expression of para-academic, outlander and nomadic forces through which the molar institution might be confronted with what it is incapable of thinking’ (Wallin, Reference Wallin, Carlin and Wallin2014, p.133). This research was born of the notion that the nomadic forces surrounding the lives of these re-emerging adult learners could enable the researcher to reach new insights into students who drop out of school that extend beyond the empirical data that shape one of the greatest political problems in education. It was an attempt to learn more about the experiences of those who made a conscious decision to go missing from their expected route to traditional high school graduation.

It was not the job of the researcher to interpret the words or bring meaning to the text. Rather, the researcher’s aim was to ‘think more’ than the discourses surrounding adult learners who have not completed high school in a traditional timeframe. The researcher wished to: (1) learn more about the life events and re-entry circumstances of learners who exited from school as teenagers and later return to complete a high school diploma; (2) (re)think the assumptions that exist in the general discourse in society surrounding the adult who lives without a high school education; and (3) explore the social and political implications of the assumptions within the literature by way of possibly thinking something else about education and its contribution to the decisions of learners to drop out of school. What might we learn about educating becoming people in high school, and can we think something new about re-entry programmes for adults?

Deleuzian philosophy and rhizomatic thinking

Bodies affect other bodies. Affects are active forces. The choice of an affective tactic to learn about the uneducated adult as an inclusive body through its lived experiences establishes the potential to launch supplementary knowledge of social and educational perception alongside the existing narratives. Affect implies an augmentation, mutation, or diminution in that body’s capacity to act. In other words, feelings are personal and biographical, emotions are social, and affects are prepersonal (Kingsmith, Reference Kingsmith2018). The affective relational and contextual intensities embodied by these adults that make up their lived experiences can now be expressed. Legitimization and visibility are gained by a group that is traditionally thought of as being socially at risk, and perceptions that typically rest in attitudes of ‘lacking’ may be influenced.

Rhizomatic (non)methodology informs rhizo intra-relational (non)method referred to as intra-view (Masny, Reference Masny2016; St. Pierre, Reference St. Pierre2019) and facilitates the unfolding of the discussions that occur among participants and researcher. Rhizoanalysis raises questions, not conclusions (Honan & Bright, Reference Honan and Bright2016; Masny, Reference Masny2016; Reinertsen, Reference Reinertsen2017; St. Pierre, Reference St. Pierre2019; Waterhouse & Arnott, Reference Waterhouse and Arnott2016), about high school re-entry programmes. The cartographies (dis)(re)tract the researcher to think about the striated constitutions of re-entry programmes that seem to ignore the life experiences of re-entry adult learners and fail to consider other curricula that may be more reflective of adult learner interests and needs. Deleuzian philosophy problematizes and reconceptualizes institutional influences often grounded in curriculum, educational policies, and assessment in order to undo normativity (Masny, Reference Masny2019). Problems that are posed allow for the possibility of a future yet to come (Colebrook, Reference Colebrook2002) and enable new possibilities in the area of re-entry adult learning.

This rhizome (de)(re)territorializes the re-entry processes of the adult re-entry learners in the study. The analytic orientation that is reflected in rhizoanalysis permeates the discussion. A brief overview of common thinking surrounding the dropout learner is included. Deleuze’s concept of rhizome and relationality of affect of the bodies (human and nonhuman) intra-acting in the research assemblage are also discussed. This discussion pre-empts the section on rhizoanalysis. The research assemblage converges on the research project with re-entry adult learners to an adult high school learning space. Focusing on sense and palpation of data, this section problematizes conventional representative and interpretive data to draw connections between questions and problems and to think intensively around the researcher’s topic.

Thinking with affect

Massumi (Reference Massumi, Deleuze and Guattari1987) described affect as power, or puissance (‘to affect and be affected’, p. xvi), because it is the driving force in the process of becoming. It is the thing that, for Deleuze, reveals that which is the body is capable. Massumi (Reference Massumi2015) explained that humans affect and are affected through encounters or events. Affect begins in relation and is all about ‘intensities of feelings’ (p. x) that produce an openness and active response to the world. Affects are not thought of as subjective feelings. They are ‘becomings that spill over beyond whoever lives through them (thereby becoming someone else)’ (Deleuze, Reference Deleuze1995, p. 127). The subject becomes other.

Human and nonhuman bodies change in capacities as they are in relation with one another (Deleuze & Guattari, Reference Deleuze and Guattari1987, Deleuze et al., Reference Deleuze, Guattarri, Tomlinson and Burchell1994). Affect (affectus) occurs within the relation, and it is different than emotion. All the things that make up the human body (bodily tissue, organs, muscle, etc.) exist in relation to one another and communicate with one another. In this relating, they ‘form an assemblage, mixture or body’ (p. 81). The people in this study and myself, the memories that we share, the recollections of some of the participants who were previous students of mine, the journals, the assignments, the spaces in which we hold discussions, the moment after the recorder is turned off and the conversation continues all make up the assemblage in this study.

When this assemblage moves beyond the body in other relations, the body becomes ‘a changeable assemblage this is highly responsive to context’ (p. 81). Deleuze & Guattari (Reference Deleuze and Guattari1987) viewed every human mind within the body as different comparing it to ‘the individuality of a day, a season, a year, a life (regardless of its duration) — a climate, a wind, a fog, a swarm, a pack’ (p. 262). Affect is really about the changing and re-making of the body in relation to the context in which it lives. The force that is produced by affect can be retained by a person, and the person may be transformed (Deleuze, Reference Deleuze1994). Sensation occurs ‘when it acquires a body through the organism, [and] is immediately conveyed in the flesh through the nervous wave or vital emotion’ (Deleuze, Reference Deleuze2002, p. 40). In addition to the idea of affect not being confused as an emotion, Colman (Reference Colman and Parr2005) referred to the concept as a prepersonal intensity corresponding to the passage from one experiential state of the body to another. The intensities produced in the research work to affect researcher becoming, participant becoming, and possibly, reader becoming.

Participants

I requested the participation of adults over the age of 25 to ensure that they had several years of living in the world without a high school diploma to possibly speak about a wide range of experiences over several years. Eight people responded to the invitation, but three had to withdraw after their personal circumstances changed, and they could no longer commit to meeting with me. Three of the five participants were former students of mine from the adult re-entry programme. Although, the other two were not in my class, we were familiar with one another as we had seen each other in the school. Pseudonyms were used to protect the idea of each participant:

Intra-views and focus group

Barad (Reference Barad2007) spoke of the authenticity of the intra-view that allows for an authentic experience found in a relational (non)method conversational approach in an authentic exchange of words. The participants consented to have our conversations recorded, so they would not be lost in my imperfect memory. Knowing that I would be able to revisit the unpredicted conversational unfolding allowed me to be at ease and give full attention to the conversations with my participants and to intra-act within the unfolding spaces of conversation.

I attempted to free up discussions in an authentic capacity by allowing the participants to speak openly and candidly of their experiences. Because ALL bodies matter through the world’s intra-activity (Barad, Reference Barad2007), I began the discussions by telling them about my work and my curiosity of their experiences, and I attempted to create a space where they might feel safe to take a lead in the discussions. I was not striated by a scripted set of questions to drive robotic responses. I invited the participants to choose the location of our discussions and engaged in responsive listening (Kuntz & Presnall, Reference Kuntz and Presnall2012) with them:

Through [intra-views] we are fully engaged and we transform perception and perspective. As thinking engages the unthought, we may speak with a resonance that expresses the limitations and potential violence of negation, … through our attempts to listen. (p. 740)

The intra-view, hopefully, allowed unsuspected ‘truths’ or (dis)(re)tractions to become affective through conversations with my participants. The poet does not use the word ‘revealed’ in her iteration of truths. She says that they can be ‘felt’ — a much more appropriate description of the revelations of the bodies in this research dissertation where spoken experiences are becoming affectus (Deleuze, Reference Deleuze1988), producing in unimagined assemblages through intra-actions of bodies coming together in space and time to talk about life experiences.

In consideration of the posthuman intra-view, participants constitute part of the elements that interact in a relational assemblage; the conventional researcher-participant relationship no longer exists (Masny, Reference Masny2016). All the elements, including researcher, become part of a transforming assemblage through relational affect. The data that is producing during rhizoanalysis are not directly experienced (May, Reference May2005). Rhizoanalysis moves away from humanist research tendencies of representation, interpretation, and categorization. Masny (Reference Masny2016) explained, ‘palpation enables sense to emerge’ (p. 672). Traditional analysis of interview data attempt to interpret meaning in the data. Data are reduced to construct findings, but posthuman researchers reject the notion of findings, arguing that the risk of misportraying what has happened is too high. Masny (Reference Masny2016) suggested that ‘palpation invites uncertainty and the untimely in an assemblage’ (p. 672). She referred to palpation as the ‘antidote to interpetosis [because] representation and interpretation de-territorialize and re-territorialize as sense-event and palpation’ (p. 672). Both Masny (Reference Masny2016) and May (Reference May2005) viewed the removal of interpretation as the removal of judgement. Instead of arriving at answers and sensible conclusions, more questions arise in face of the problems posed, and resistance to fix the problem emerges. The idea of knowing something for sure is becoming impossible. The (non) methodological aspect of rhizoanalysis is a different way of doing research. It is a different way of thinking … nomadically taking the researcher to new thinking, new questioning, new innovating.

The concept of intra-view guided the discussions with participants in my dissertation. The intra-views served as the largest contribution to learning about the experienced assemblages of the people in my study. Although I had prepared some questions ahead of time, the conversations became open-ended. The intra-views varied in length, and a couple of them extended beyond the recording. Conversations continued in the leaving of the spaces on walks to our vehicles, in a stairwell, on a bench on the sidewalk. The intra-views provided a venue for the participants to speak about their experiences around their childhood, their schooling, and their life events leading them back to complete their high school diploma. I was free to engage in the unfolding of the conversation, not as an outside observer, but as an active participant. As researcher, I did not control the conversation. I simply got them started, and they unfolded in their own ways.

Honan (Reference Honan2014) posed that posthuman research (non)methods should provide an opening for researchers to experiment, to play, and disrupt what is taken for granted in qualitative research methods. St. Pierre (Reference St. Pierre2013) said that postqualitative ontologies ‘do not assume there is a given, a real world (data) that can be gathered together (collected) and described (analysed and unknown)’ (p. 225). The de-centering and de-privileging of the interview does not equate to eliminating the intra-view. Thinking with Deleuze and Guattari meant that I could experiment with ways to ‘allow the collision of forces to join other enactments and assemblages’ (p. 738). The assemblages eventually became known, but they intra-cluded previous readings, schools, family relations, memories, journals, interviews and dreams. Even the settings of the intra-views and the timing of the intra-views came into play as participants shared their experiences.

The entanglements of bodies (Nordstrom, Reference Nordstrom2013), which I prefer to think of as intra-tanglements, came together to affect an intra-realational becoming assemblage. The intra-view is not traditional qualitative research. It is a place for becoming relational connections between participant and researcher, a place for genuine, undirected conversations to emerge between participants and researchers through open and authentic dialogue. I was extremely privileged to hear the personal experiences of these amazing people. I think…

They taught me. They opened to me. They trusted and they shared. I listen, I try to hear, I try to … just listen … what is becoming? (Author’s Research Journal, May 2019)

At the end of the individual meetings, each participant was invited to be part of a group meeting to discuss their experiences. Focus groups have been useful in ‘reinforce[ing] the data-gathering process’ (Xerri, Reference Xerri2018, p. 143). Like the intra-views, I did not want to treat the group discussion as an event controlled by myself. I hoped the participants would speak freely in the discussions, and a natural unfolding of the discussion would occur as it had in the former meetings. Three participants had originally expressed a willingness to attend the focus group discussion. Only two of my participants ended up joining the group discussion (Cam and Jimmy) due to a last-minute change in the schedule, but it was extremely interesting to engage with Cam and Jimmy in the discussion that ensued. I was particularly struck how they wanted to hear about my life experiences as well. At one point in the conversation, as they spoke about their own relationships and how relationships can have impact on our decisions in life, they drew me into their reflections:

Jimmy: Every year we go; once a year we join up with these random group of guys and go on a canoe trip together. Again, it’s just an acquaintance that is carried on. There is just a difference in your relationships later in life. When you’re in school you are there every day and you meet them every day. Once you get a job wherever you do your job. Friendships end up being kind of that group that you connect with unless you do something outside of that.

Intra-viewer: That’s interesting.

Cam: Relationships of convenience I’d say.

Jimmy: Yup.

Intra-viewer: Your conversation reminds me of my own children. My daughter who is in her early 30’s lives out in [city eliminated]. You talk about high school drama, Cam…There was a lot of drama surrounding her friends in high school and so on. Always a lot of tears amongst the girls. I would always say to her, ‘You realize these are your high school friends. In ten years time you are never going to…But interestingly ten years later those girls are like thick as thieves, and they don’t live in the same place. One lives in [city eliminated]. One lives in [city eliminated., two live here in their hometown and they’re like a sisterhood.’ They consistently make connections and have regular visits. Relationships play big roles in our lives, don’t they?

The intra-view is merely one connection in the hub of connections that is produced in the research machine. Discussions may migrate in directions not imagined by the researcher, but these unsuspected lines of flight are part of the nomadic process during rhizoanalysis. Intra-views have the potential to ‘lead to responses that are far more personalized’ (Xerri, Reference Xerri2018, p. 140). The intra-views in this research included many personal contributions:

Ella: I have many health problems; you’d think I was an 80-year-old or something (laughing). I recently got diagnosed with dysplasia where my oesophagus muscles don’t work right. So, they are trying to figure out the cause, but I have to take these pills to help me swallow and I keep choking and it’s sickening. So, it’s weird.

Jimmy: It doesn’t matter what you have. You can be a kid, or you can be an adult, but there is certain stuff that you are going to have; be it your bed, be it a couch, be it a chair, be it a pillow, be it a box of history. Anything, you are going to take that stuff with you and already there is a whole bunch of that history that we have just thrown in the garbage because really when you look at it, it’s not going to mean anything 20 years down the road anyways. No one is going to look at it, so we get rid of it. Stuff in my life has really been nothing more than just clutter. It stresses me out, it stresses my relationships, and it just causes worry about finding money to pay for all the stuff. I don’t want financial stress to destroy my relationships. When I figured that out, it was easy for me to get rid of stuff.

‘Jimmy has no need for material things in his life. His whole philosophy of ‘less is better’ has freed him from the ‘rat race’ of life. I wonder if his experiences associated with not having a high school education has contributed to his ability to find the sense of "peace" that he exudes. He completed high school much later, but not for material gains. Perhaps another disruption of common sense?? He is much more focused on relationships’. (Researcher’s Interview Journal, June 4, 2018)

Other sources of (non)data

Outside of the individual and group discussions, some of the participants offered to share some of their completed assignments that they kept after graduating from the adult programme. Most of the assignments involved writing pieces or selections that posed various challenges. Each piece was a part of the individual becoming and became part of this rhizome research. Jimmy wrote in one of his in-class reading journals:

I have completed the reading of this book. It is probably the first book I’ve completed since I quit school. It is the first time I read and watched a movie about a book. This book, and your whole class so far, has opened my heart and my mind to go places. I have put up walls or have forgotten and felt alone for a long time. Some of those situations have been very painful in my life and I really did not want to deal with them. (Jimmy’s journal, Nov. 24, 2017)

One week later in the journal he wrote:

I picked a quote from the book on p. 151. It said, ‘I think,’ he says, smiling, ‘God overdid it.’ Yup. God overdoes it!!! Call it writers block, call it laziness, call it my mind getting in the way…Call it whatever you want. Permission to speak frankly? I had a chance 27 years ago to sit in a classroom and complete Romeo and Juliet and get my grade 12 diploma. For whatever reasons I am now in your class today. I am very thankful for who you are and the lessons you are teaching me in this class. Thanks for opening my mind and my heart in all of the lessons you have put in front of us to do. You may think ‘oh it is just part of my lesson plan!’ but I do believe it is more than that. I have completed the reading of this book. It is probably only the fourth book I have completed since I quit school. It is the first time I read and watched a movie about a book. This book, and your whole class so far, has opened my mind and my heart to go places. I have put up walls or have forgotten and left alone for a long time. Some of those situations have been very painful in my life and I really did not want to deal with them. Back to God overdoing it…yes he was. We serve a great God who knows what he is doing and that is why we are where we are today. Just wanted to say I am having a real hard time completing this assignment and that I really have no excuses. I just have to let go and write. So as I let go and continue I just wanted to say ‘THANK YOU’.

Mapping of (Non) data and rhizoanalysis… de-re-territorializing moments of affect

Gerrard, Rudolph, and Sriprakash (Reference Gerrard, Rudolph and Sriprakash2017) described postqualitative inquiry, such as rhizoanalysis, as throwing open the basis of research practices found in methods, methodology, and the claim to know. Masny (Reference Masny2013) spoke of postqualitative approach as nomadic, but claimed, ‘it is important to qualitative research because it is a game-changer: transforming life’ (p. 345). She further purported, ‘Rhizoanalysis focuses on what it produces and how it functions as a way to conceptualize research-as-event’ (p. 345). It creates the potential to think beyond what is already known because the research is thought of as Deleuzian experimentation where the researcher has no idea what the results will be. Deleuzian researchers do not focus on emerging patterns or meaningful structures, but they look for that which may have otherwise remained invisible in typical analysis. No attempt is made to discover likeness, sameness, or patterns in the data. Data is deconstructed to map the intensities that emerge during intra-views.

Difference is found in the effect of the constant interaction between virtual and actual. Masny (Reference Masny2016) explained, ‘the virtual becomes actualized only to become virtual again. It is the forces of difference that allows for creation and invention to happen continuously’ (p. 667). Rhizoanalysis works within ‘transcendental empiricism in which sense expresses not what a text means or is, but rather its virtual potential to become’ (Masny, Reference Masny2013, p. 341). The (non)data are not viewed as evidence of truth to what ‘something’ might mean. The (non)data produce connections as the researcher intensely studies the sources to map the assemblages that enable the researcher (and readers of the research) to make sense of the research event. The researcher exposes the experiences through rhizomatic mapping whereby ‘sense emerges through the power of affect’ (p. 342). In other words, the ‘report findings’ are no longer taken up as a representation, but as cartography known as map making (Waterhouse, Reference Waterhouse2011). Deleuze (1990/Reference Deleuze1995) said, “Never ‘interpret’ experience, experiment” (p. 87). The researcher studies her assemblage and experiments with the relational flows and connections that occur among all the elements; she maps the first reactions to data as moments that are ‘interesting, remarkable, or important’ (Deleuze et al., Reference Deleuze, Guattarri, Tomlinson and Burchell1994, p. 82).

An affective response to (non)data is often felt before it is thought. This visceral responses in this project often happened before the transcriptions were completed. They happened at moments in my discussions with my participants, and I made note of them in my journal immediately following our meetings. They were important in the cartography of mapping the assemblages. Semetsky (Reference Semetsky2006) described these moments as the ‘firstness of intuition’ (p. 433), always preceding cognition. It is a way of knowing before we ever fully think something. It happens in the ‘immediacy of experience’ (p. 434), (dis)(re)tracting us to think more about connections and analysis. It is a vital part of the process.

Scenes of visceral moments

The time was set. The location was agreed upon. A meeting was arranged. The room was small. The people in the room sat around the table partaking of some refreshments, and conversation ensued…

Researcher: Tell me about your life journey so far. Tell me about the things that stand out vividly in life that you have encountered so far … the things that are important, the people that are important in your life, events that sit in your memory bank. Maybe you would like to start with some memories of your original high school days. You decide.

Randy: I have my mom and two sisters. But for a while now, the military has been family. I excelled when I was in elementary school but after my father passed away it’s like my home dynamic changed quite a bit. So, it became very difficult to focus on school and it was about that time that I got into high school that it started to kind of like; I started my gradual descent into dropping out of school. (Intra-view, May 10, 2018)

[Insert]: An event in Chernobyl, many years before Randy was even brought to Canada by his family, served as a moment of affect in his own becoming. The deterritorializing moment in Randy’s father to leave a home country, in time, became part of the story in Randy’s deterritorializing moment to leave school and join the military. This is an example of the connection of assemblages in rhizomatic production.

Lara: When I think of high school … I was falling behind. I wasn’t attending and just wasn’t there. School wasn’t there for me. There was no interest in it at all and yeah at 17; I think it was 17 when I stopped because I got pregnant. Then I miscarried and all hell broke loose and school was over (laughing). Then my mom passed away when I was 18. (Intra-view, May 3, 2018)

Jimmy: Who is Jimmy? Jimmy is a married guy with 3 kids. At 17 I had cash in my pocket. I was working a job. I don’t really need school, right? It was just the mentality of ‘what’s this going to do for me?’ and personally I had no future, I had no plans. I never had a lot of conversation about my future with my parents. I had failed other grades and even in those other grades they came and talked to me but never punished me or said, ‘Hey you did bad.’ And to this day it still astounds me that my parents never talked to me, never asked me, never said nothing. (Intra-view, May 5, 2018)

Ella: I was hoping that I would get an idea of what I wanted to do while I was in school. But I’ve tried nursing before. I went as an adult student, a mature student so I didn’t need my grade 12. But my husband wanted me to do that. I didn’t want to do it. So, I plugged through it for a while and then I just didn’t like it. It was too much responsibility for me. I don’t want nobody’s life in my hands and the nurse was always talking about medication or how people die. I didn’t like it, I didn’t want to do that. (Intra-view, May 18, 2018)

Cam: I made friends with the ‘drama’ people in a school where I transferred, my new high school. There was a girl I really liked who strung me along for the most part. So, that was a big consumption of my attention and the drama that came between her and the other guy that she was with, you know. It was a triangle almost. It was her, then me and another guy. And it just made my life really stressful and frustrating, and I just stopped going to school. It was easier to skip than to deal with the awkward situation of being around these people that were making my life uncomfortable and difficult. (Intra-view, May 10, 2018)

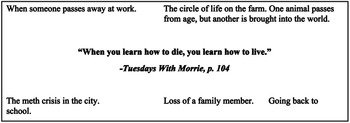

[Insert]: Life experiences can disrupt the way people think about things or the way they may believe the direction their lives are taking. Each of the participants speak about something that deterritorialized their early education experiences. Various events/people contribute to the assemblages that are created, deterritorialized and reterritorialized. Each of the participants spoke about family members or significant relationships. Figures 1 and 2 depict a sample of classroom activities completed by 2 of the participants while reflecting on their own life journeys.

Randy: The military has had a big impact on me. I am trying very hard to be more open and I think I made great strides in that … to being more open to other people’s opinions and being less like; just less rigid about things. Understanding that there is a grey area sometimes to things. In the military everyone has a very similar viewpoint and even if they don’t, if they are below me in some way I make them believe my viewpoint. Because, the military is not a democracy, right?? (Intra-view, May 10, 2018)

Lara: One thing that stands out for me is my graduation. I am a better me being educated, knowing more. It was a big step in my life. I think I was trapped in my own self worthlessness. (She pauses for several seconds to think, and I see a tear in her eyes.) … But then she smiles … And I actually got my niece to come back and she did it. She came to my graduation and when she saw me graduate, she said, ‘I’m going back to school!’ because she was a drop out too. I was proud of that moment. I felt like maybe I was an example to help her make a good choice. (Intra-view, May 3, 2018)

Jimmy: I believe nothing happens by accident. (Jimmy pauses, he looks down and I notice he is crying. I am quiet. I give him time. After a few seconds, he looks up and he smiles. He continues …) There is a purpose behind every part of life. I am so thankful for everything in my life, even the things that others might see as difficulty. For example, there is no way I would have finished my grade 12 this late in life if I hadn’t lost my business, moved here and had the availability now to just cycle from work to downtown to my classes and do a course twice a week. Then pass the courses and get my grade 12. There would have been no way. We never know what can happen, even when people might think the world is falling apart around them. But, I am faithful too, and I believe in God. He sustains me. He has given me so much in the people that I love and who love me … what else is there? ‘Things’ do not matter. Actually, the less we have, the less we have to worry about. There is freedom in having less ’stuff’. It is too bad more people couldn’t see that. People might actually live a whole lot happier. (He still speaks with tears in his eyes; yet, he is smiling.) (Intra-view, May 5, 2018)

Cam: Recognizing a lot of my flaws and not necessarily accepting them but accepting that I need to work on them. So, the lack of emotion that I show people. The connections that I feel I don’t make. I’ve noticed that I’m very distant with the people that are close in my life and that is a very shady thing to do because they are great people. They are there to support me when I need them and I’m not giving them that back in return. I’m realizing that I may not want to spend time with people. I may just want to sit there on my own and do my own thing but as much as your life is your own, your life is not your own. But, maybe I am just different that way, you know? Doesn’t everybody want to be with somebody? I don’t always think that way. I guess, your life is the effort that you put into the relationships around you as well. (Intra-view, May 10, 2018)

Figure 1. Word splash depicting significant life events of participant.

Figure 2. Power point slide depicting life connection to personal reading selection.

After we had concluded the taping of our conversation, Cam explained:

Cam: I have not put in much effort with my relationships really. But, for a long time I have felt very used by people. It has only been in the last few years that I have come to see another side of people. It is too bad because I may have lost some very good people by the time it took me this long. But, coming back to school, for example … you know … maybe because people are older and have more experience, but they seem more real to me now, more like they really are interested in my journey too and not just their own. Their support is real. I should not just push everyone away. I have to battle through this wall of doom that I probably have created.

[Insert]: What is the wall of doom that he speaks about? Does that battle (war machine, Deleuze & Guattari, 1980/Reference Deleuze and Guattari1987) disrupt ‘something’ that leads to peace? He reminisces in his thinking. He says he has not put much effort into his relationships, but something is also being produced when he says that people seem more real to him now. In the research process, they are mapped; they are relational.

[Exit]

Discussion

The participants in this study decided to leave their high school life to move away from the ground of reasonable experience and action, from top-down learning. They reterritorialized to the unknown, away from an ordered and hierarchical structured system of education (Bassul & Kayumova, Reference Bassul and Kayumova2016). However, they returned to the system. They challenged educators to think about institutions that are highly structured and to consider the possibilities that could exist by deterritorializing the system to ‘enable discontinuity and ruptures’ (p. 291). In listening to the participants in my study, I was struck by their own descriptions of controlled and mitigated actions that existed within their own education experiences.

Randy: Basically, I dropped out of school because I had to start working. Remember I told you that when I got to grade 11, I started to show some violent tendencies and the government got involved with our family. They called it protective custody. They split me and my sister up. They put me with a very abusive family I was just a very young little innocent Ukrainian boy. … The damage had been done. I got more aggressive at school and the policy was zero tolerance for any aggression, so the police got called every time. It seemed like the principal didn’t really care about me. He just had a policy book that he followed all the rules by. If I showed any aggression, the response by the school was to call the police. It is hard to focus on education when you’re more concerned about surviving and finding food and shelter. I could not go to school and work at the same time. My school timetable had no flexibility for me to accommodate any kind of job. I tried to get classes later in the day, but I could never get enough credits. What would you do? I don’t know of any teachers who teach night school at high school, do you? (Intra-view, May 10, 2018)

Lara: I don’t think the school really knew what to do with me. I had a pretty rough teenage life, drinking lots and then I got pregnant. I didn’t really apply myself, but nobody really cared. One counsellor just told me straight up one day, ‘Just wait until you come of age and just drop out. You don’t really fit school anyways. Maybe you will find something better’. I don’t think anybody really tried to keep me there. (Intra-view, May 3, 2018)

Jimmy: When I was in younger grades, I repeated a couple grades. School wasn’t the easiest thing for me. So when I got older I got a job and just started making money. That is really why I left. Nobody questioned me. Today I might be called A.D.D. or something would have been slapped on me or some initials, some label they would have thrown on me. When school was hard, I didn’t want to do anything. I don’t know why schools don’t do more for kids who don’t do so well with book learning. I could do lots with my hands you know, like carpentry and mechanics. Everything in life … there is a bombardment of education, you always have to learn new systems. I think the school system needs to look and say, ‘Okay what are kids actually; what’s their future? What are they going into’? And keep current or flexible to where they are at. That would be a big factor in keeping kids in school. … They should see you are not an idiot because you dropped out of school, because they could see where I got from life to this day.

Cam: I had no motivation when I was in high school. Any class I passed it was like 50% only. I failed Grade 12 English. I actually found school easy. … I was not a robot in high school and I’m still not a robot. I’ve also spent a lot of time thinking about how hard I am on myself and I am not easy on myself and it really puts me into a rut when I get thinking about that… I cripple myself and it spirals and I need to do better. I can do better too. I can let things go, but when I see myself as worthless … and lots of my teachers told me I was worthless in their own ways. You can tell when they think that way about you just by the way they interact with other students who are easier to teach and tell them everything they want to hear. They just make their jobs easier. I had one teacher who told me straight up that I would never amount to anything.

Each of the participants had different experiences. I listened to their departure from a molarized system into unknown territory. I learned more about the becoming, once-unschooled, adults before me. In the relational doing of research, I was part of the assemblage.

Jimmy: I am not sure how to explain what it was like for me to come back to the adult collegiate, but I know that it seemed like the courses were easier. They made more sense to me. Math, especially, seemed to make more sense. I always had trouble with math when I was younger. … I don’t know, um maybe it’s just after doing mechanic work and stuff that numbers make more sense to me. And, like I said before …. It was the first time I ever read a whole book front to back when I came back to school. I never thought I would do that. And, you know, I actually do read more now than I ever did before. I find enjoyment in it actually. I never ‘got’ that before.

Ella: The biggest surprise for me coming back to school was actually passing physics. I even got a good mark. I never would have done that back then. I could barely do multiplication when I was 16. Now, I passed my Grade 12 math and physics (She laughs). That just seems crazy to me. I don’t really know what I will do with physics, but it sits on my transcript.

Randy: You know it was never that I really found school hard. I just never made it a priority. I guess I never put much value in it. But, I guess as an adult I could make more connections to what was being taught when I came back to school. The stuff we read in the English class was what surprised me the most I think. It’s funny how the things in a book can make you think about your own life. It’s like a part of your soul gets woken up that you didn’t even know was sleeping.

Some of the rhetoric of the discourses around schooled/educated bodies surface in the discussions with the participants. They speak about the pressures placed on them by others to finish high school, the need they place on themselves to make something more of their lives, the goal to make more money, the ‘common sense’ ideals that occupy most people’s minds. Yet, they also speak of the desire to help others, be examples to others, live with ‘less’ to be free of the economic demands and time constraining pressures of ‘keeping up with the Joneses’ (Jimmy Intra-view, May, 2018). While I do not believe that education is not important for society’s continued becoming, perhaps a shift in thinking might emerge about how the education of people can occur. More importantly, people should not have to feel any less proud of their own becoming if their lines of flight take them to unusual places of production. People’s lives are complex. Is it possible that current discourses that position the educated body in places of privilege might also serve to marginalize other bodies whose lines of flight take them in different directions. Surely, the path to socioeconomic sustenance can be experienced differently, more complexly. It should not have to reflect a stratified binary state of being educated/schooled or not being educated/schooled. Human becoming embodies much more value than is simply determined by its level or amount of schooling. Is it possible to rethink what life-long learning might look like outside the perspective of stratified education systems?

Wallin (Reference Wallin, Carlin and Wallin2014) explained the goals of a system to ‘produce’ the ideal graduating student. The quest to graduate this product begins from the early years when the child first enters the doors of a school. The ideal child becomes shaped into the ideal graduate, designed to become the ideal adult. Predetermined rules govern children’s behaviour. Curriculum is regulated and neatly packaged for teachers to deliver to students. Best practices, based in evidence-based approaches for optimal learning are adopted for praxis. Provincial exams and regular assessments occur to measure students’ development and skill levels. Interventions occur as achievement results deem necessary. The system is destined and designed to produce a carefully crafted product, one that embodies the ideal graduate.

The dropout is a disruption to the system and causes a Deleuzian revolutionary war machine (Deleuze & Guattari, Reference Deleuze and Guattari1986) as it resists by deterritorializing the molarizing tendencies of the school system. The system’s product goes ‘missing’. The product is now constructed to be at the fringes of society, invisible now to the system that marches forward in the process for those that remain. The product is resistant to rigid structures that, at one time, were main sources of information and knowledge. Presently, the instant sourcing of knowledge found through the Internet (Ramani, Reference Ramani2015), forces a reconstituting of what schools can provide to learners. Possibilities exist in the (re)thinking around education and schooling. A disruption to the paradigm’s current existence might be beneficial to some students who just do not see themselves as ‘fitting in with school’. Technology provides opportunity to think differently about the purpose of schooling and what ‘school’ can look like. Is it possible to see difference between the purpose of schooling and the purpose of education? Perhaps the current system of education does not have to serve as the basis for the production of the graduated body into the adult world. Or perhaps, the system can provide options, lines of flight, that lead to the becoming educated body. A paradigm shift to disrupt the binaries of the either/or path of educated/noneducated may be useful. What other options exist to navigate one’s becoming in the world. The participants in this study traversed various and complex paths. Eventually, the dominant social norms that ‘legitimize’ an individual through the holding of a high school diploma played a role in the return to school of these participants. Their life experiences that were gained through various occupations and places did not ‘count’ in their educational journey. They had to return to high school. There was no option to navigate future choices without the diploma. Despite their abilities, their experiences, their commitment to personal growth, the molarized system does not allow them to bypass the high school diploma.

After dropping out of the system that was shaping and producing a graduating product, these participants dropped back into the same system. The curriculum was the same. The credits required to graduate were the same. The only thing that has changed was the setting and the age of the people around them. How is it that the becoming experiences of these re-entry adults is not considered in the completion of their ‘right of passage’? The participants in this study each experienced various transforming events in their lives that have contributed to their unique life assemblages. Yet, the system of education continued to demand a stratified completion of certain courses that somehow translated into the completed graduated product, despite the years that have passed between dropping out and dropping in. There was no (dis)(re)traction in the programme of re-entry to think something new… Suddenly the concept of (dis)(re)traction emerges. And suddenly, the problem emerges … at the exit of the rhizome.

St. Pierre (Reference St. Pierre2019) claimed that thought is not recognition and representation but creation. It is involuntary and does not originate with human consciousness. The concepts of Deleuze et al., Reference Deleuze, Guattarri, Tomlinson and Burchell1994 become ‘an act of thought … operating at infinite … speed’ (p. 2) as we address a real problem and reorient our thinking. Some re-entry adults may continue in their education, and the completion of specific course may be prerequisites for admission to future programmes. Some may return to high school simply to complete that which was never finished. Perhaps the choice to return is simply part of their own becoming journey that fulfils a need to inspire someone else or build upon their own self-efficacy. The reasons for return are multiple and complex. The re-entry programme is rigid and fixed. No account is made for life events that are always expanding upon our becoming learning journey. No option to tailor the re-entry process even exists. The curricula is not designed for adult programming; yet, it is the only one available and its completion is mandatory for graduation.

The lines of flight that have been created, and are still to be created, constitute the potential for further research around adults who live with minimal schooling. What is it that brings some adults back to finish high school later in life? Why do some never return? How are some able to find independence and happiness with a minimal education and others endure hardship and rely on outside supports to live day to day (as is expressed in typical literature that discusses the ‘realities’ of high school dropout)? Some of the discourses that exist in the stratifying spaces of schools and society have been identified in this research project. They do not necessarily serve to answer the questions that continue to exist, but they do illuminate some injustices and inequities within school systems and within the values that are held by society. For example, the stratifying processes described by Fong & Faude, Reference Fong and Faude2018) to register children for Kindergarten disadvantage late registrants in the process of school choice:

Despite equal access in theory, bureaucratic structures such as timeline-based lotteries hinder many families, particularly those disadvantaged already, from full participation. Inequality in school choice outcomes and experiences thus results not only from families’ selections, the focus of previous research, but also the misalignment of district bureaucratic processes with family situations. (p. 242)

Stratifying processes do not work for all people, despite their best intentions. The policy of a government or an education system to prepare and educate its product for optimal future life experiences is well intended. It just does not work for everyone. New directions for education research and practice are vital in the midst of the complexity that we find in a changing world. These directions do not have to be prescriptive and should never result in finite possibilities. Semetsky (Reference Semetsky2008) urged scholars in continued experimentation with nomadic education that will enable the constant generation of thinking something else to creatively meet the needs of complex and becoming generations. What will this look like? What kinds of supports will be needed with(in)(out) of schools to reflect the thinking of something else. How might we think something to have all students remain visible and included?

Acknowledgements

None.

Financial Support

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflicts of Interest

None.

Ethical Standards

This research has been approved by University of Regina, Brandon University, and Assiniboine Community College ethics committees.

Shelley Kokorudz is an assistant professor in the Faculty of Education at Brandon University. She is currently conducting research in inclusive Nature-Based Learning Pedagogy in early years education as an alternative schooling option for young children. The focus of the research is to learn more about the intersectionality of instructional practices in natural spaces with Indigenous ways of knowing and to gain a better understanding of how to infuse Indigenous perspective into curriculum. She is an advocate of nature-based learning as a means to (re)connect children to the earth to deepen their knowledge and appreciation for sustainable choices in human care for the planet. Furthermore, nature-based learning provides a viable alternative to schooling known to improve overall mental and physical health of students and to capitalize on their natural instincts for exploration and imagination by increasing their capacity for higher order thinking in natural spaces.