Children are situated precariously within the global environmental crisis. Exploitation of the earth’s resources and the resultant devastation of eco-systems has resulted in what has been declared a ‘climate emergency’ (Morton, Reference Morton2018). Across the scientific community, evidence suggests that human activity is largely responsible for climate warming trends and that all species on earth are threatened (Coates, Reference Coates2003; The National Aeronautics and Space Administration, 2018). In the Australian context, the energy sector relies heavily on burning fossil fuels and the government continues to support extractive industries of non-renewable resources. Children are particularly invested in the continued wellbeing of the planet as the impacts of today’s actions will affect the earth for generations.

While debates about climate change have been ongoing for decades, the contemporary uprising of school-aged children demanding action has been largely attributed to the efforts of Swedish teenager, Greta Thunberg. Thunberg was 15 years old in 2018 when she first sat on the steps of the Swedish Parliament in Stockholm instead of attending school. Every day for 3 weeks leading up to the Swedish election she held a sit-in demanding that the government act seriously and urgently on climate change (Fridays for Future, 2019). What began as a one-person protest drew increasing media attention, and by the end of the first week, a group of supporters. After the election Thunberg returned to school except for Fridays, which became a weekly sit-in event. Her actions instigated a global movement that became known as #SchoolStrike4Climate (SS4C) and #FridaysforFuture.

On November 30th, 2018, thousands of Australian school children attended a nation-wide school strike in protest against the Australian government’s inaction on climate change (SS4C, 2019). A second mass school strike was organised for March 15th, 2019 (SS4C, 2019). By this stage the strike had expanded its global reach and was attended by more than 1.5 million strikers in simultaneous strike actions performed in over 2000 locations from more than 100 countries (Glenza, Evans, Ellis-Peterson & Zhou, 2019).

Controversially, Australian Prime Minister Scott Morrison responded to the strike with the following statement:

‘We don’t support the idea of kids not going to school to participate in things that can be dealt with outside of school. We don’t support our schools being turned into parliaments. What we want is more learning in schools and less activism in schools.’ (in Lock, 2018)

His comment was widely reported in the media and attracted significant debate. The Prime Minister was not alone in his sentiments. This statement reflects long-held discourses around children and childhood, in which children are seen as incapable of participating in political discussions and in need of protection from nefarious influences. Such discourses simultaneously trouble and inform the goals of environmental education. Environmental education has long been recognised as a site of political and social knowledge, and the Australian Government’s blueprint for education aspires to educate young Australians who are ‘active and informed citizens’ who ‘work for the common good’, particularly in relation to natural environments (Ministerial Council on Education, Employment, Training and Youth Affairs [MCEETYA], 2008, p. 9). However, schools and their organisational structures often struggle to provide a context that promotes the environmental educational goals of critical inquiry and reflection (Stevenson, Reference Stevenson2007). The SS4C, on the other hand, are a site outside of formal schooling where the goals of both environmental education and the broader education system are realised.

In this paper, we analyse prominent discourses presented via the Australian media surrounding the March 2019 SS4C in Australia. The synchronisation of these mass global rallies by school-aged children was highly publicised and sparked significant political and social debate. The media holds great power to shape narratives by selecting and framing commentary to influence public opinion (Qazi & Shah, Reference Qazi and Shah2018). We argue that the social and political commentary of these strikes demonstrate both anticipatory and protectionist narratives of childhood, and in doing so, contradict the educational goals set by Australian governments for young Australians. These narratives disregard the ways children purposefully engage in prefigurative activism and exercise agency to circumvent their exclusion from formal politics.

Narratives of Childhood

In Western societies, ‘childhood’ is understood most commonly as an age-based category, constructed through shared social understandings of rationality and maturity. Children are humans below the age of 18 years (although this age category changes depending on the country and context). James and Prout (Reference James and Prout2005) state that childhood is a product of the social realities within its time and these can include a multitude of factors such as location, era, and material factors. Government-mandated age barriers that intersect with social attitudes control when young people may legally drink alcohol, obtain their driver’s licence, and consent to sexual activity. Such activities are deemed to be adult in nature and beyond the capacity and responsibility of immature and developing young people. In contrast, responsibility is placed upon young people with regards to committing offences against the law to the extent that Australian children can be criminally detained from the age of ten years (Amnesty International Australia, 2020). The incongruence between the placing of responsibility for criminal matters and the removal or exclusion of responsibility for civic matters demonstrates the power and control inherent in narratives of childhood.

Similar to older adults, young people experience age-based discrimination as a result of ageist narratives (Bergmann & Ossewaarde, Reference Bergmann and Ossewaarde2020) which function to maintain these age categories. Childhood innocence is framed as intending to protect children, but has a dual effect of diminishing their opinions and political actions and of limiting their opportunities so as to protect that ‘innocence’ from climate concerns (Raby & Sheppard, Reference Raby and Sheppard2021). News media shapes ageist narratives by presenting young climate activists with terminology such as ‘pupils’, ‘absentees’, ‘dreamers’ and individually as ‘young heroines’, all of which imply naivety (Bergmann & Ossewaarde, Reference Bergmann and Ossewaarde2020). In doing so, the hegemony of paternalistic governance and climate scepticism is maintained.

For several decades, sociologists have critiqued the ways in which children and childhood are defined, categorised, constructed and understood. Anticipatory and protectionist perspectives have been identified as dominant ways in which adults in public, private, and academic spheres narrate children’s experiences (Qvortrup, Reference Qvortrup and Doxiadis1989). These two narratives problematically assume a monolithic experience of childhood. The anticipatory narrative of childhood tells a story of children maturing and developing as they look forward to full participation in society upon reaching the threshold age of legal adulthood. Central to this anticipatory maturation process is tuition by means of various forms of socialisation, including schooling. This understanding of childhood is problematic. For example, deeming a person fit for adulthood on the basis of age implies that maturation is a definitive process with a start and finish point. Rather, socialisation continues throughout adulthood (Leonard, Reference Leonard, Qvortrup, Brown Rosier and Kinney2009). Additionally, maturity and competence are not entirely based on age (Thorne, Reference Thorne1987). Children develop maturity along individual trajectories according to their own experiences and characteristics, with many demonstrating responsibility in younger years. Likewise, individual adults vary in abilities and maturity, and these characteristics are not rigid. Arguably, the personalities and behaviours of some adults could see them considered incapable, irresponsible and/or irrational, and even child-like (Thorne, Reference Thorne1987). Despite the marked variation in the maturity and ability of all people, Western societies such as Australia continue to embrace the constructed boundary of adulthood at 18 years of age. Children are perceived to be incomplete beings on the basis of age, rather than the inherent characteristics of individuals (Castaneda, Reference Castaneda2001). This view simplistically renders children as human ‘becomings, rather than beings’ (Qvortrup, Reference Qvortrup2009, p. 643).

This idea persists, with recent narratives of young people continuing to render them in the stage of ‘becoming’. As an age-based hierarchy, the role of childhood is presented as a stage of movement to the future without recognising their concerns and voices as relevant in the present (Brennan, Mayes & Zipin, Reference Brennan, Mayes and Zipin2021; Raby & Sheppard, Reference Raby and Sheppard2021). Through political participation in the school strikes, young people reject current schooling and politics as not addressing their concerns, both present and future (Mayes & Holdsworth, Reference Mayes and Holdsworth2020). The assumption that young people need adults to empower them is directly challenged by their action of walking away from their education to take up space in the public realm and participate in politics (Brennan, Mayes & Zipin, Reference Brennan, Mayes and Zipin2021). As a result, their education progresses outside of the classroom through their engagement as informed and connected citizens.

Alongside anticipatory narratives of childhood, children are often seen as in need of protection (Qvortrup, Reference Qvortrup and Doxiadis1989). In protectionist narratives of childhood, children must be shielded from matters considered to be of adult concern, such as politics and economics. Some aspects of society’s protectionist attitude towards childhood stem from the inherent greater physical capacity of adults and intends to be caring and nurturing (Thorne, Reference Thorne1987). The perceived characteristics of childhood, such as immaturity, incompetence and irrationality, are insufficient cause for such categorisation which sees children excluded from full capacity and participation in society. Research points to the position and function of children within society and demonstrates that understandings towards them produces a language of power which is disempowering and marginalising (Qvortrup, Reference Qvortrup and Doxiadis1989; Thorne, Reference Thorne1987). Children’s relations and interactions within society are embedded with power and authority with children being labelled as ‘dependants’ and adults as their ‘guardians’ (Leonard, Reference Leonard2015; Thorne, Reference Thorne1987). Through dominance and authority, children are recipients of adult culture and resistance to this socialisation is considered deviant.

Both anticipatory and protectionist narratives of childhood fail to take into account the ways in which children do actively determine aspects of their own lives, and contemporary studies increasingly examine how children exercise agency. James and Prout (Reference James and Prout2005) discuss how ‘children are not just the passive subjects of social structures and processes’ (p. 8). In the playground, children already negotiate their position in peer groups and the (in)equality of roles and distribution of resources. Such agentic behaviour in early play lays the foundation for later political intent (Rosen, Reference Rosen2017). Similarly, children agitate for and create change in their own homes in the here and now, for example, reminding family members to turn off lights or adjust water usage (Walker, Reference Walker2017).

An emerging narrative of childhood focuses on children’s exercise of their agency beyond their personal lives which can be intentionally and purposefully political. This experience of childhood should not be essentialised; the ability of children to exercise agency depends on their position within social structures like race, gender, global position, and socio-economic status. In a range of contexts, studies demonstrate how children’s agency reaches into the political sphere, affecting a variety of causes worldwide. Digital technologies have emerged as a vital tool in enabling children’s activism by allowing them to easily exchange information, organise, recruit and take action (Green, Reference Green2020). In doing so, children prefigure this new narrative about themselves as active political agents demanding to be heard, despite their exclusion from formal politics. Far from being passive recipients of adult culture, young people frequently insert themselves into the political agenda. In Hong Kong, for example, young people organised to lobby against the proliferation of commercial brand-scapes. Although their actions were ineffective against corporations and governmental will, they were able to gather local support and establish DIY networks and co-operate to prefiguratively reject consumerism on a smaller scale (Lam-Knott, Reference Lam-Knott2020). Such examples increasingly contribute to alternative narratives of childhood which recognise young people’s active voice reaching into politics. Rather than simply existing outside of formal political realms, the process of excluding children from these realms in turn shapes the nature of political discourse, with children constituting the boundary of what is allowable (Nakata, Reference Nakata2015).

Children and Prefigurative Activism

In democratic political systems, children are seldom given formal opportunities to contribute their opinions, shape policies and elect policy-makers who govern their worlds. Leonard (Reference Leonard, Qvortrup, Brown Rosier and Kinney2009) states that it is an ongoing failure of electoral systems to not include children. Despite this deliberate structural exclusion from politics, children do find ways to participate politically. Their exclusion creates the need for innovation and creativity to locate non-traditional, non-formal, and potentially deviant methods of political expression. Whilst this political expression takes many forms, here we use the term ‘activism’ to frame the various activities and intents with which children participate in politics. Children’s activism activities allow them to be included in political narratives and, in a sense, force their uninvited voices to the political table. As such, childhood political participation, on the very basis of it being conducted by children, is a form of prefigurative activism; ‘a mode of thinking and organising that helps make sense and fill the intermediate vacuum in the space where grand social change is still in the making’ (Szolucha, Reference Szolucha2017, p. 121). This prefiguration has long-term effects by allowing participants to ‘begin to imagine an alternative to systems of power and liberate their thinking from those traditional structures’ (Petray & Gertz, Reference Petray and Gertz2018, n.p.; see also Day, Reference Day2004; Petray & Pendergrast, Reference Petray and Pendergrast2018; Wright, Reference Wright2011).

The anticipatory and protectionist narratives of childhood, discussed above, are a useful tool to understand how children’s activism is perceived. Through activism, children enter into political conversations from which they have traditionally been excluded. Yet children’s political agency is often minimised as adults frame their efforts through protectionist and anticipatory ideas. For example, when examining youth street riots in Belfast, Carter (Reference Carter2003, p. 276) found that media portrayed the activities using terms such as ‘recreational rioting’, ‘local entertainment’ and ‘creating their own fun’. Such narratives result in the belittling of children and youth’s action by refusing to validate their voices. Instead, their actions remain enveloped in the realm of what is perceived as childish play; this is reminiscent of Thorne’s (Reference Thorne1987) work/play binary where children’s actions are devalued as ‘play’, while adults’ activities are afforded the status of ‘work’ to signify importance and value.

In the sections which follow, we examine the responses to Australian children and young people’s involvement in the 2019 School Strike 4 Climate. Our analysis of the commentary demonstrates the anticipatory and protectionist narratives present in the public commentary about children’s engagement in the school strikes, as reported by mainstream media, and shows how children continue to be positioned in Australian society.

The Research Project

This research presents a qualitative case study of public commentary of the 2019 SS4C, as mediated through news articles. News organisations (such as the private and public broadcasters included here) frame how audiences engage with public issues, by ‘selecting events, opinions, facts, images and information’ (Cooper et al., Reference Cooper, Olejniczak, Lenette and Smedley2017, p. 79). Here, we analyse how a range of commentators’ statements construct children and children’s prefigurative activism as an object of discourse (after Foucault, Reference Foucault1972), rather than analysing the subject-positions of the speakers. While media organisations favour particular groups of speakers, it is the narratives which are produced through the media that contribute to ongoing public discourse, and as such, are the object of analysis here. Within these statements, the children attending strikes are often homogenised into one essentialised group of ‘strikers’, ignoring potential differences in children’s motivations and understandings of the SS4C.

The primary data are Australian online news articles dated from 1st–29th of March 2019. This time range was chosen in order to analyse the narratives reported not just on the day of the event (15th March 2019), but also 14 days before and after the strike. Whilst excluding broader commentary and analysis in the months preceding and following, this timeframe captures the most immediate representations from politicians and the general public about childhood and children’s activism. Although we focus here on the March 2019 strike, an earlier strike took place on 30th November 2018. The 2018 strike was frequently referred to and intertwined with narratives surrounding the build-up in the planning stages.

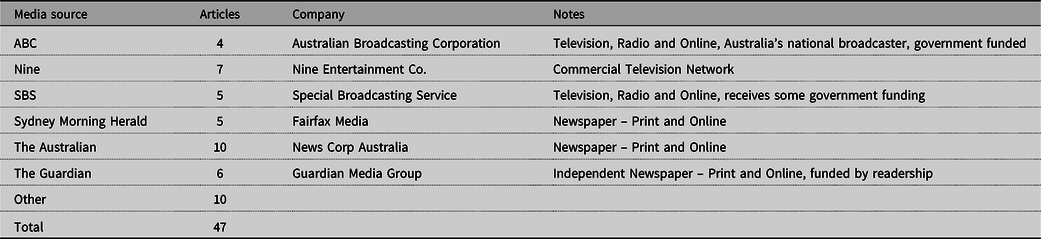

We used the search engine Google to manually search for text-based media (some of which contained embedded multimedia, including images and video), using relevant search terms including ‘school strike for climate’, ‘climate strikes’ and ‘Australian school children news’. All duplicates reported across multiple platforms were removed from the Google search results and a total of 64 articles were included in the final data set. These ranged across six main media sources and several less prominent sources (Table 1). Rather than analysing the sentiment of the articles written by journalists, the news articles were a source for direct quotes from adults commenting on the SS4C. A total of 297 such direct quotes were extracted from the articles for analysis. The commentators whose responses were presented in the media were mostly politicians or well-known social commentators. These included present and former Members of Parliament and government ministers, as well as local council representatives, and celebrities. Some commentators were reporters, hosts and opinion writers. Expert voices such as climate scientists, education, and other non-governmental organisation representatives were also included. Other commentators were members of the public, such as parents, teachers or supporters. News articles favour particular commentators, with a tendency towards recognisable public figures and polarising commentary. This commentary is then mediated by journalists and editors. While we cannot know whether quotes were taken out of context or misrepresented in articles, several commentators appeared more than once in the dataset.

Table 1. Media source summary for case study data collection

Coding of these commentaries was undertaken by the first author and cross-checked by the second author. An initial review of the data suggested that anticipatory and protectionist themes were common in the ways that adult commentators framed childhood and the activism of children, along with some commentary that discussed children’s agency. As such, the decision was made to undertake a deductive analysis. Coding for commentary that reflected anticipatory, protectionist, and/or agentic narratives was developed by identifying key terms/phrases directly from the data. Key terms in commentary that follows anticipatory themes were phrases implying deviance and included words such as ‘rules’, ‘punishment’ and ‘obligation’. Protectionist key terms included any phrases suggesting concern for the children’s welfare, such as ‘brainwashed’, ‘pawns’, ‘manipulation’ and ‘confused’. A limited amount of commentary around young people’s agency was also noted by their expression of support or focus on climate solutions. In coding, it became evident that much of the agentic commentary could be understood as anticipatory and/or protectionist, and as such, was incorporated into these two meta-narratives. Following this, we thematically analysed the quotes within each meta-narrative in order to document the shape of these narratives in Australian media. These quotes are presented here, and where possible are attributed to their authors.

Anticipatory Narratives

Anticipatory narratives regarding childhood speak to the exclusion of children from full participation in society as they await the passing of years to reach adulthood (Qvortrup, Reference Qvortrup2004). During those years, children are expected to engage in appropriate socialisation as provided by the social structures in their specific context (Leonard, Reference Leonard2015; Thorne, Reference Thorne1987). In our analysis of adult responses to the SS4C that were captured by mainstream media, we saw anticipatory narratives indicated by reference to rules, calls for strikers to be punished, and attempts to discredit child activists. Anticipatory narratives were the more prominent theme, and the comments demonstrating these narratives were almost exclusively made by politicians, with fewer contributions from commentators, community members, and experts. Each of these three themes relegate children to an inferior category as per anticipatory narratives of childhood. In this way, children are deemed not yet fit for involvement in matters of adult concern and, instead, are expected to model obedience and conformity.

Children’s (and adults’) lives are guided by social structures and norms. Within the structures, standard codes of behaviour are expected to be learned and adhered to – these are the ‘rules’ that many adult responses to the SS4C considered strikers to have broken. In the SS4C, the rules referred to most relate to the formal education system which requires compulsory attendance for all school-aged children at the school where they are enrolled. Children are expected to use their time at school to learn from their educators in preparation for full participation in society upon reaching adulthood. Absorbing adult culture occurs through socialisation and this is not expected to be a reciprocal process of shared influencing but rather a passive acceptance by children.

Many adult responses focused on these rules, sometimes invoking legal expectations:

‘The law is clear and always has been, kids are required to be at school on school days. Around 1/5 of the year there is no school so there are plenty of occasions for kids that are passionate about a whole range of issues to engage in extracurricular activities.’ Rob Stokes (NSW Education Minister)

Others echoed the importance of following the rules of the education system but were supportive of the children, expressing sentiments which viewed the school strikes as a unique learning experience to complement their classroom education, and a meaningful opportunity to demonstrate their learning in practical action. While recognising agency, some of these comments still reflect the anticipatory narrative that childhood is a time for socialisation to proper adulthood.

State-funded schooling is provided to all Australian children and it is both a right and a requirement to attend. For some groups of Australian children, such as Indigenous students, school absences are heavily monitored and pre-occupy politicians, policy-makers and media (Waller, McCallum & Gorringe, Reference Waller, McCallum and Gorringe2018). However, exceptions are often made and it is not uncommon for children to miss school due to extended holidays, family reasons, and on cultural events such as Melbourne Cup Day (even in states where it is not a public holiday). Despite these excused absences, attending protests about climate change inaction is positioned in the data as lacking judgment and maturity:

‘There are parents, teachers and politicians who encourage school children to absent themselves from school to protest on climate change. They may think the issue justifies their stance. They’d be wrong; it’s a misguided and irresponsible attitude and should be stopped. Attendance at school is considered vital for children and society.’ Community member

In the two examples cited here, children’s considered decisions to participate in formal prefigurative activism are seen as trivial in comparison to the formal education that they would otherwise receive that day at school. Compulsory attendance in formal education is perceived as vital to assisting these ‘human becomings’ (as per Qvortrup, Reference Qvortrup2009) to reach their full status in society; any absence from this education is cause for admonishment rather than responding to the arguments put forward by the children. Furthermore, in the case of the community member quoted above, children are not even perceived as capable of having reached this position by themselves. Instead, it is ‘parents, teachers and politicians’ (that is, adults) who encourage children to forgo a day of school (discussed further in ‘protectionist narratives’, below).

To manage the perceived deviance of these child activists / ‘rule-breakers’, some adult responses sought punishment in the form of either a tangible consequence, such as physical or other disciplinary action, or general disapproval and non-acceptance. Jarrod Bleijie, then Queensland Shadow Minister for Education, said:

‘This is nothing more than wagging school and any student who participates in the strike during school hours should be punished accordingly.’

Media reports indicate that in some instances, students missing school for the climate strike were threatened with fail marks or truancy notices. Schools and individual teachers, as well as parents, who encouraged and/or supported the climate strike were similarly threatened by government authorities. As Leonard (Reference Leonard2015) states, children who resist socialisation are viewed as faulty or deviant, and punishment is the response to quash or repair such deviance when it is detected (Durkheim, Reference Durkheim and Lukes1982). A community member reflected this mentality by commenting:

‘Why wouldn’t every truancy officer in the state be down at that protest checking these kids out?’

This statement reflects the community member’s view of not only expected obedience of society’s rules, but also a firm understanding of the mechanisms in place to enforce or punish. The representation here is that it is appropriate to use punitive measures to refuse children their chosen means of political expression. This desire for punishment demonstrates the ongoing influence of anticipatory narratives where children are expected to be obediently waiting, following the rules, and not yet competent enough to participate in political discussions. However, some were more concerned with the urgency of the climate crisis, arguing that children do not have the time to wait because by the time they reach voting age, it will be too late. A few demonstrated the agentic narrative, celebrating the children’s desire to re-write the possibilities of a future for the planet and this points towards the prefigurative aspect of the children’s activism whereby they are attempting to create change in a space beyond their permitted reach.

Children who participated in the SS4C, especially those more prominent in organising events, were often discussed in ways that attempted to discredit them. In many of these cases, adult responses focused on issues that were irrelevant to the cause or to the activism. The aim of raising these irrelevant issues is seemingly to remove credibility from the children and the debate. School strikers were dismissed as opportunistic truants, or ‘waggers’. Many adults claimed that if the protest action was planned on the weekend or anytime outside of school hours, then children would not bother with the cause, even though the nature of a strike requires it to be held during normal ‘work’ hours:

‘Children should protest on weekends or after school rather than participating in tomorrow’s walkout over climate change.’

Bill Shorten (then Leader of the Opposition, the Australian Labor Party)

Others questioned the young people’s ability to comprehend the issues they were protesting, as per the anticipatory beliefs that children do not have the appropriate political nous until they reach the age of 18:

‘A so-called strike by high school students is as facile as one by the self-styled unemployed workers’ union—of no relevance, futile, likely only to harm oneself and inclined to make one look foolish. Failure to grasp this basic logic suggests these wannabe activist warriors could benefit from as much classroom time as they can get. When they grow up, they will realise that wisdom comes through maturity and life experience, not social media or peer pressure.’

Community member

Other adult responses expected children to give up on modern living before they could speak out about climate change caused by fossil fuels and industry. A community member stated:

‘What are we teaching kids today? To be a bunch of virtue signallers? They go home in Mum’s SUV after their strike to a heated house planning their next overseas trip while millions of Indians burn twigs and cow dung to cook dinner. What hypocrisy.’

Such opinions highlight anticipatory perspectives by attempting to discredit the children’s actions. This example suggests that children are not capable of understanding the complexities of how changes to dependence on the fossil fuel industry may impact on the personal comforts they afford within the home. The term ‘hypocrisy’ works to render the children’s actions as unworthy of consideration on a political level.

Belittling terminology is used as a tactic to infantilise the protesters and demonstrate they are far from competent social beings:

‘… you’ve got seven or eight-year-old kids barely out of nappies being involved in a strike. A lot of these students are barely literate or numerate. I think it’s absurd.’

Kevin Donnelly (Australian Catholic University, social commentator)

In all these examples, commentary does not engage with the issue of climate change. Distracting factors are raised, such as the strikes being an opportunity to miss school, the hypocrisy of modern living and children’s capacity to understand the issue. In anticipatory fashion, these point to the expectation that children must wait until adulthood before their opinions will be counted and their voices validated.

Debate concerning children’s activism crosses many sectors in society in varying prominence and intensity. Children are excluded from democratic electoral systems and activism is perceived as deviance from the rules of society. As per Leonard (Reference Leonard2015) and Thorne (Reference Thorne1987), understandings of childhood are embedded with a language of power, and this is evident in the analysis we present here. Narratives surrounding child activism first attempt to reiterate the rules which children must obey. When children continue to protest despite the rules, then threats of punishment occur, as per Durkheim’s (Reference Durkheim and Lukes1982) suggestion that society’s structures have measures in place to repair or quash perceived deviant behaviours. Further, children’s anticipatory status is reinforced by the language of power embedded in the political and social narratives surrounding child activism. Language enables the debate to relegate children’s actions to the realm of childish behaviour instead of granting validity of political expression. A tone of harshness and, on some occasions, nastiness appears where children’s political actions contradict the long-held understandings of childhood itself and the issues to which the children are protesting.

Protectionist Narratives

The protectionist narratives regarding children describe how children are to be ‘preserved, developed and protected’ (Qvortrup, Reference Qvortrup and Doxiadis1989, p. 86). Thorne (Reference Thorne1987) acknowledges the greater capacity that adults possess and how that translates into a protective stance over children. Most adults have greater physical strength and access to resources than most children do, and adults are expected to share the benefits of this greater capacity with the children in their lives (Thorne, Reference Thorne1987). Terminology like ‘dependants’ and ‘guardians’ is evidence of the power differential between adults and children. Protectionism is, in part, caring and nurturing and may stem from honourable motives, but the power imbalance can also have an undermining effect. This dimension is, at its worst, exploitative and abusive and, in terms of political participation as in this discussion, is one of disempowerment. In the commentary surrounding the SS4C, protectionist narratives expand on anticipatory themes in order to present an explanation as to why children are participating politically when it is believed that they do not have the capacity to understand complex adult issues. Welfare concerns are raised, and adults who encourage and support child activists are accused of brainwashing or using the children as pawns. The commentary also incorporates a sense of obligation for loyalties that might be expected considering the nurturing and care children receive. Protectionist narratives were primarily evoked by community members, followed by politicians and, to a lesser extent, commentators.

In the adult commentaries analysed here, there was a sense that children were being ‘brainwashed’ by adults around them. The term ‘brainwashing’ is used here in reference to how children are represented as incapable of their own free-thought and decision-making, and instead their opinions must originate from their parents or teachers. One community member stated, for example:

‘A lot of those kids are too young to understand what it’s all about anyway, it would be something that’s forced on them by their parents.’

By using the words ‘forced on them’ the speaker silences the children’s own understanding and their desire to act of their own knowledge. Likewise, the following quote speaks of declining education standards in order to bring notions of ignorance and naivety:

‘It seems certain that Australian educational standards are in decline, in no small part related to poor teaching standards and to a curriculum loaded with social activism. That teacher-initiated student strikes should take place comes as no surprise, even if it has resulted in a day without much-needed education.’

Community member

This statement immediately disempowers the protesters’ claims that the rallies are student-led by deliberately naming them as ‘teacher-initiated’. Many of the brainwashing narratives incorporate terms such as ‘gullible’, ‘ignorance’, ‘idealistic’ and ‘manipulated’, all of which remove credibility from the children and claim that political opinion and action can only stem from the adults around them. Several supporters defended the children’s knowledge and ability by pointing out how the critical thinking learned in the classroom had led to action through collaboration and creativity – demonstrating, again, the emerging narrative of children as active political agents. However, we saw many more examples in which the accusations of brainwashing were targeted at adult environmental activists with claims that children are being used as political pawns for causes or financial gain.

‘Parents have a right to know who is influencing their kids, what are their real motives and who is paying for it. … The Australian public will be cynical about a so-called student-led strike that is actually organised and orchestrated by professional activists. … It is appalling political manipulation.’

Dan Tehan (Education minister)

The words used in many quotes were noteworthy, many implying brainwashing to the point of being abusive, such as, ‘tax-payer funded eco-warriors’ who are using kids as ‘political pawns in a game’ or as part of a ‘cynical political strategy’. These clearly describe a sentiment that adult activists are brainwashing children to further their own political cause. Following these claims, the protectionist narratives begin to imply themes of harm. For example, former Australian Prime Minister and (then) Liberal party politician, Tony Abbott says:

‘I think that school teachers that encourage activism in their kids, certainly activism in school hours, are actually doing their kids damage.’

Such representations imply the need for protection from the adults responsible for the brainwashing or for encouraging activism. Welfare concerns range in intensity from practical matters of road safety and children’s supervision when out in public, to statements of intentional harm and disadvantage. Some supporters of the children argued the contrary, stating that the precarious future of the planet (not children’s concern for this future) was the cause of harm towards children, and that adults were failing to protect them from the dangers of climate change. This is still a protectionist narrative, but it recognises children as exercising agency in response to legitimate concerns. Such data were limited. More protectionist concerns were for the psychological and emotional welfare of the children. In this quote, environmental activism is likened to a cult and/or child abuse:

‘The climate-change-for-kids thing is child abuse, pure and simple. … It’s tragic. You see the results where the kids are demotivated, disinterested in their school work, disinterested in their futures because they believe … that 12 years from now it’s all over. … I bandied around the word climate change cult last week. Have the discussion, but this cult-like behaviour where you get the kids to believe passionately that the world is coming to an end, it’s all over, they’ve got no future. I think its sick. I think its child abuse.’

Rowan Dean (Commentator, Sky News)

Similar messages describe climate activism as the result of a ‘pessimistic attitude’ about the future. This is in line with the dominant protectionist perspective on childhood that children should be shielded from matters of adult concern (Campiglio, Reference Campiglio, Qvortrup, Brown Rosier and Kinney2009).

Alternative commentary in this theme extends protectionism into obligation; that is, obligation of gratitude that should be demonstrated by children in return for their protection and provision. An element of guilt or lack of gratitude is implied upon children who protest. It refers to the perceived values and goodness that many Australians are fortunate to enjoy and implies that obedience is an obligation as a result of that good fortune. As Hood-Williams (Reference Hood-Williams, Chisholm, Buchner, Kruger and Brown2005) discusses, obedience and conformity are expected as a result of the nurturing and maintenance that adults impart to children. SS4C commentary specifically referred to economic wealth and innovation of which the Australian industrial sector is currently a large portion. Debates argued that children should not complain but be positive and grateful for the circumstances they experience in the present, while disregarding that those same circumstances are responsible for the threat to their long-term future.

A community member commented:

‘I hope the striking schoolchildren are also taught that without coal exports and coal-fired power stations, Australia will become an economic basket case. Neither these children nor most of their parents have any idea what an economic recession is like. But I doubt this will be mentioned at their climate change protests.’

In those words, the community member is implying that no complaints should be made against fossil fuels for economic reasons. Today’s children have not experienced the numerous historical recessions that Australia has suffered and this community member is of the opinion that without the mining industry another recession would be imminent. This viewpoint incorporates an attitude that children should feel a sense of gratitude and are obligated to refrain from criticising an industry which allows them the comforts they enjoy.

Discussion and Conclusions

In our analysis of the reporting about the SS4C, it is evident that children were largely not seen as capable citizens. They were predominantly constructed as deviant rule-breakers who would benefit more from formal education than activism. Their actions and understanding were framed as the result of adult coercion and brainwashing. In line with the protectionist nature of childhood, children’s activism was not perceived as the result of independent thought. The narrative framed the protest in terms of welfare concerns, where the psychological and emotional wellbeing of children was brought into question. Together, these narratives construct childhood as a life stage where children should wait patiently, undergoing formal instruction so that they too can one day contribute to society. Venturing outside of this construction of childhood is deemed cause for children to be punished, and concerns to be raised regarding their welfare. The data we analysed also tend to treat ‘children’ as a single homogenous category with no discussion of intersecting disadvantage, and the narratives we found in our analysis treat childhood as the primary factor affecting political participation.

But such representations of childhood ignore the rich and clear scientific evidence about climate change which suggests that there is no time left to wait. This is also reflective of a widespread narrative of climate denial from Australia’s political leadership and key mainstream media. Thus, the coverage of the SS4C reflects this tension in Australia between those who believe the climate is changing, and those who do not, or who argue that the change is unrelated to human activity. Supporters of the children’s protest defended their strike actions and acknowledged that children will be most affected by the decisions they are formally excluded from. The Australian Curriculum’s Cross-Curriculum Priority of Sustainability provides school students with contexts to understand the chemical, biological, and physical systems and how they change in response to human activity; as well as ask questions and think critically in response to environmental and human changes (Australian Curriculum, Assessment and Reporting Authority, 2015b). By taking this learning from the classroom to the real-world scenario of climate change activism, they have acted prefiguratively by reaching into the adult realm of politics and attempting to re-write the future of the planet.

This is why we argue that children’s agency is prefigurative – children are attempting to create the change here and now while waiting for formal structures to catch up (Szolucha, Reference Szolucha2017). While adults debate whether children should be permitted to participate in political action, children have found the collective power to ignore the structural expectations while publicly expressing their political voice: “students have literally walked out of a form of schooling (and politics)” (Mayes & Holdsworth, Reference Mayes and Holdsworth2020, p. 100). This challenges the protectionist narrative which argues that children should attend school to learn and be socialised for adulthood, and positions the SS4C as an important location for experiential learning about both climate change and politics. Adult narratives also questioned their rational understanding, belittled their actions, and claimed the children were used and brainwashed for political gain. The strikes suggest that children perform prefigurative activism, and this alternative reading of the SS4C problematises the common narratives of childhood articulated by so many adult commentators in our research. Prefigurative activism, by definition, refers to activism which reflects the vision of society that is aspired towards (Flesher Fominaya, Reference Flesher Fominaya2014). Prefiguration can also take on a more symbolic meaning by referring to the ideology of activists who display what Graeber (Reference Graeber2014) has described as a ‘defiant insistence on acting as if one is already free’ (p. 85). In this sense, prefiguration incorporates a refusal to operate by the traditional, formal and institutional structures that are in place in society (Graeber, Reference Graeber2014). The activism presented here is indeed prefigurative, and as such, works against protectionist and anticipatory narratives which suggest that childhood is not the place for engaging in political conversation. Children are working for environmental and social justice despite being excluded from any input in such issues. They are defiantly refusing to be bound by the traditional institutions (Graeber, Reference Graeber2014).

Children are themselves at the forefront of crafting this new narrative that recognises their own political agency through taking action despite no formal recognition of their political voice. By acting prefiguratively, they are producing a new narrative which shifts anticipatory discourse from their age and development, to the need for societal systems and processes to incorporate their capacity and voice as valid political action. They are contributing to knowledge production and creating a prefigurative space, even if short-lived, in which they have a valid opinion on political issues (Cox & Flesher Fominaya, Reference Cox and Flesher Fominaya2009; Flesher Fominaya, Reference Flesher Fominaya2014; Szolucha, Reference Szolucha2017). In so doing, they also implicitly challenge the narratives that suggest they should be excluded and/or shielded from formal politics, or climate change. This prefigurative activism aligns with the stated goals of the education system – that of educating ‘active and informed citizens’ who ‘work for the common good’ (MCEETYA, 2008, p. 9). Political activism is not just an example of experiential learning. Instead, educators must consider how young people are already engaged with the learning outcomes of the Australian Curriculum: Civics and Citizenship, such as understanding how resilient democracies are sustained (Australian Curriculum, Assessment and Reporting Authority, 2015a). Climate activism suggests students have already engaged with the goals of the Australian Curriculum. As such, educators can draw on students’ activism to develop learning opportunities, promoting an even deeper understanding of Australian civic society and democratic participation. These educational implications of the SS4C sit in contrast to the anticipatory and protectionist narratives presented here.

This paper discusses children as a category constructed by media sources, and the adults quoted within them. These are powerful influences of public opinion, and these narratives are important to understand even though they do not represent the experience of children themselves. A child’s parent, teacher, or any adult who consumes such narratives uncritically may influence how that young person feels about their ability to participate in the SS4C, and how they might be politically engaged in general. These mainstream media narratives might also influence how school decision-makers treat absences by those in attendance at the SS4C, or more broadly how they de/prioritise environmental education within their school. Understanding these narratives as narratives is useful to help young people critically interpret the way they are represented in the media; and to navigate their conversations with adults. Further research may look at how the voices and experiences of diverse children are represented within the media. Children’s political agency in the context of climate strikes should also be explored further, including examining ways that they understand and navigate how they are constructed within societal discourse. Relegating all children to a disempowered, apolitical position fails to capture the unique expression of their political contributions, ignores the increasing support for their inclusion in adult dialogues, and masks the intersections and nuances of their vested but precarious outlook for the future.

Acknowledgements

The data and some of the analysis presented in this article contributed to Nita Alexander’s BA Honours thesis. We appreciate the constructive feedback on that work throughout Nita’s Honours study, especially Dr Nick Osbaldiston.

Financial Support

At the time of collecting the data for this article, Nita Alexander was a recipient of the JCU Douglas Fry Bursary. At the time of writing the article, Nita Alexander receives an RTP scholarship in support of her PhD project about children’s activism.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to report at the time of publication.

Nita Alexander is a PhD candidate in Sociology at James Cook University. As an activist and researcher, their project explores young people’s experiences of activism and children’s political participation.

Theresa Petray is an Associate Professor in Sociology at James Cook University. She researches in the area of Aboriginal activism, self-determination, and nation-building, and is particularly interested in the ways in which seemingly marginalised people exercise agency.

Ailie McDowall lectures in Indigenous Studies at the Indigenous Education and Research Centre, James Cook University. Dr McDowall’s current research is in research education, focusing on the preparation of scholars to work across Indigenous and non-Indigenous knowledge standpoints.