Introduction

The disparity between health and educational outcomes for AboriginalFootnote 1 and non-Aboriginal Australians remains a current issue. Completion of year 12 has been deemed the ‘holy grail’ of Indigenous education (Smith et al., Reference Smith, Trinidad and Larkin2015) however improvements in these numbers have not translated into further engagement in study, training or employment (Rutherford et al., Reference Rutherford, McCalman and Bainbridge2019). For rural students, the Halsey review (2017) noted a decreasing completion of year 12 and pursuit of further tertiary education with increasing remoteness.

This study aims to investigate aspiration and motivation of Aboriginal students living in a rural township. According to Gale et al. (Reference Gale, Sellar, Parker, Hattam, Comber, Tranter and Bills2010) two key barriers to higher education for all students are low academic achievement and low motivation and aspiration. Much of the available literature on Aboriginal Australian student aspiration and motivation is from research conducted in remote areas. The concept of a ‘narrow aspiration window’ externalises educational disadvantage rather than assuming a ‘lack within’ students (Harwood et al., Reference Harwood, McMahon, O'Shea, Bodkin-Andrews and Priestly2015). This study will examine how rurality influences intrinsic attributes, relationship networks and contextual factors to narrow the aspiration window of Aboriginal students.

An appreciative enquiry approach (Trajkovski et al., Reference Trajkovski, Schmied, Vickers and Jackson2013) is consistent with an Aboriginal ‘strengths-based’ approach to education (Armstrong et al., Reference Armstrong, Buckley, Lonsdale, Milgate, Kneebone, Cook and Skelton2012). The authors acknowledged their ‘colour blindness’, and their tendency to acquire deficit notions regarding marginalised students achieving in a racially and socially stratified society (Lazar and Nicolino, Reference Lazar, Nicolino, Sharma and Lazar2019; Walter and Aitken, Reference Walter, Aitken, McKinley and Smith2019). Interview questions were formulated and reviewed by a local Aboriginal Research Advisory Group made up of Elders and Aboriginal community members with an interest in health and education. Questions focused on post-secondary school plans, aspirations, important relationships, and perceived barriers and enablers to the high school learning experience.

Aspiration and motivation in policy

The 1990 National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Education Policy (NATSIEP) identified five long-term goals addressing higher education aspirations and literature exploring this concept has emerged (e.g. Behrendt et al., Reference Behrendt, Larkin, Griew and Kelly2012; Frawley et al., Reference Frawley, Larkin, Smith, Frawley, Larkin and Smith2017). The Higher Education Participation and Partnerships Program (HEPPP) government initiative provides universities financial incentives to enrol students from low SES backgrounds (Gale and Parker, Reference Gale and Parker2013; Frawley et al., Reference Frawley, Larkin, Smith, Frawley, Larkin and Smith2017). As such, studies have examined the relationship between university-led initiatives and aspiration for tertiary education (e.g. Pechenkina et al., Reference Pechenkina, Kowal and Paradies2011; Whiteford et al., Reference Whiteford, Hunter, Jamie, Pitson, Breckenridge, Elders, Vemulpad, Harrington and Jamie2017).

The Halsey review (2017) highlighted key issues for regional, rural and remote education. Student aspirations are shaped by ‘attitudes and beliefs about the value, attainability and relevance of higher education and further education and training’ (Halsey, Reference Halsey2017). These aspirations are shaped by a range of factors, including family, community environment and socio-economic background as well as interactions between students themselves and their knowledge of the wider world (Halsey, Reference Halsey2017).

Motivation in the literature has traditionally been focused on an epistemological ‘centering of Western frameworks’ (e.g. Magson et al., Reference Magson, Bodkin-Andrews, Craven, Nelson and Yeung2013; Bodkin-Andrews et al., Reference Bodkin-Andrews, Whittaker, Harrison, Craven, Parker, Trudgett and Page2017). Merely identifying and understanding practices that motivate students is not enough—culturally reinforcing paradigms need to be prioritised (Bodkin-Andrews et al., Reference Bodkin-Andrews, Whittaker, Harrison, Craven, Parker, Trudgett and Page2017). This is particularly important for research and teaching initiatives for Indigenous students (Preston and Claypool, Reference Preston and Claypool2013; Bodkin-Andrews and Carlson, Reference Bodkin-Andrews and Carlson2016; Walter et al., Reference Walter, Martin and Bodkin-Andrews2017). Further refinement of research scales is needed to measure student motivation in a culturally safe manner (McInerney, Reference McInerney2012).

The authors have sought to give voice to Aboriginal young people to discuss how motivation and aspiration impacts their secondary school experiences. A review of the literature found that academic self-concept, cultural connectedness, relationship networks, educational culture and teachers, and regionality influence Indigenous student aspiration and motivation.

Factors impacting aspiration and motivation

Self-concept

Positive levels of academic self-concept and school aspirations are related to lower levels of academic disengagement in both Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal students (Bodkin-Andrews et al., Reference Bodkin-Andrews, Dillon and Craven2010). However, Aboriginal students are significantly more likely to report lower academic self-concepts and school aspirations (Craven and Marsh, Reference Craven and Marsh2004; Bodkin-Andrews et al., Reference Bodkin-Andrews, Dillon and Craven2010). Craven and Marsh (Reference Craven and Marsh2004) found more Aboriginal students aspired to leaving school early, attending Technical and Further Education (TAFE) institutions and were less likely to know about what job or further education they could pursue following school. Craven and Marder (Reference Craven and Marder2007) demonstrated that poor academic self-concept can contribute to a self-fulfilling prophecy of failure. Lower career aspirations, poor career advice by close relationships and a lack of government assistance can reduce self-concept (Craven and Marder, Reference Craven and Marder2007). Recently there has been a focus on academic, physical and art self-concepts and the role these play in achievement and aspiration among Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal students (Yeung et al., Reference Yeung, Craven and Ali2013). For rural Indigenous communities, identification as science learners was closely linked to motivation for science learning (Middleton et al., Reference Middleton, Dupuis and Tang2013). Oliver and Exell (Reference Oliver and Exell2019) demonstrated self-identification as an Aboriginal person contributed to successful workplace transitions.

Cultural connectedness

Lowe et al. (Reference Lowe, Harrison, Tennent, Guenther, Vass and Moodie2019b) discussed the levels of social, cultural and epistemic conflict that have historically existed between the school system and Aboriginal students, families and local communities. Faircloth (Reference Faircloth2009) highlighted how education can serve as a tool to dissociate students physically and culturally from the places from which they come, particularly if they are from a rural area. This creates an ambivalence towards education that can be exacerbated if the purpose of schooling is in conflict with the values and beliefs of rural communities (Faircloth, Reference Faircloth2009). The Halsey review (2017) noted considerable evidence of educational success in remote Aboriginal communities when the curriculum is aligned with the contexts and traditions of the community. The question remains if this is true of rural communities as well (Halsey, Reference Halsey2017).

Motivation and cultural identity is associated with stronger educational and life aspirations (Bodkin-Andrews et al., Reference Bodkin-Andrews, Whittaker, Harrison, Craven, Parker, Trudgett and Page2017). Examining students from other stigmatised ethnic groups illuminates the positive effect of culturally belonging in school and its impact on student academic aspiration, motivation and performance (Murphy and Zirkel, Reference Murphy and Zirkel2015). These groups are vulnerable to negative stereotyping and threatened social and academic identity while they seek to belong at school (Murphy and Zirkel, Reference Murphy and Zirkel2015).

Relationships networks

Over 90% of Aboriginal secondary school children identify support from family, friends and the school as integral to assisting them with completion of year 12 (Smith et al., Reference Smith, Bullot, Kerr, Yibarbuk, Olcay and Shalley2018). The influence of strong relationships and role modelling on academic aspiration in Aboriginal Australians is complex and multifactorial (e.g. Luzeckyj et al., Reference Luzeckyj, McCann, Graham, King and McCann2017; Patfield et al., Reference Patfield, Gore, Fray and Gruppetta2019). Smith et al. (Reference Smith, Bullot, Kerr, Yibarbuk, Olcay and Shalley2018) highlight the importance of connection to family, culture and community in remote Australia and the positive impact this has on future pathways into higher education.

Walker (Reference Walker2019) interviewed Aboriginal youth not currently engaged in education and found that family and community life could also be a barrier to future aspirations. Many remote families are additionally disadvantaged by poor literacy and this results in the continuing alienation of Aboriginal communities from educational decision making (Lowe et al., Reference Lowe, Bub-Connor and Ball2019a, Reference Lowe, Harrison, Tennent, Guenther, Vass and Moodieb; Ratcliffe and Boughton, Reference Ratcliffe and Boughton2019).

Many Aboriginal Australians are first in their family to complete secondary school and pursue higher education (Luzeckyj et al., Reference Luzeckyj, McCann, Graham, King and McCann2017). Rural Aboriginal students must additionally navigate an educational experience with limited career role modelling opportunities. Larkins et al. (Reference Larkins, Page, Panaretto, Scott, Mitchell, Alberts, Veitich and McGinty2009) explored the higher educational aspirations of young Aboriginal women and found a lack of role modelling and clear pathways for achievement made their goals seem unattainable. Aschenbrener and Johnson (Reference Aschenbrener and Johnson2017) found educational mentors helped at-risk Native American youth feel motivated to pursue their educational futures. Aboriginal Australians often lack mentors or role models that have navigated the post-secondary school transition and support may come from stakeholders outside the community (Irwin et al., Reference Irwin, Callahan and Duroux2015).

Educational culture and teachers

Halsey (Reference Halsey2017) found that bringing curriculum ‘to life’ while still maintaining valid and reliable educational assessment can be a challenge in the rural context. This is due to a critical question about educational purpose with many students asking ‘am I learning so I can leave my community, am I learning so I can stay locally, or am I learning so I have a real choice about what I do?’ (Halsey, Reference Halsey2017). Irvin et al. (Reference Irvin, Meece, Byun, Farmer and Hutchins2011) found that a sense of school valuing and belonging was predictive of educational achievement and aspiration for Indigenous youth in rural communities. The importance of classroom instruction practice, interpersonal relationships and the motivational school climate more broadly were found to impact the motivation of Native American students in rural schools (Hardre, Reference Hardre2012).

The role of teachers and school support staff in facilitating success for Aboriginal students in high school is well recognised (Whiteford et al., Reference Whiteford, Hunter, Jamie, Pitson, Breckenridge, Elders, Vemulpad, Harrington and Jamie2017; Osborne et al., Reference Osborne, Paige, Hattam, Rigney and Morrison2019). Aboriginal students rely on the ‘energy, interest and goodwill of teachers’ in establishing supportive programmes (Whiteford et al., Reference Whiteford, Hunter, Jamie, Pitson, Breckenridge, Elders, Vemulpad, Harrington and Jamie2017).

In the Aboriginal Australian context, classrooms can be a primary site of conflict where the power held by the school is enacted on the students by teachers (Lowe et al., Reference Lowe, Bub-Connor and Ball2019a). There is a need for teachers to engage students ‘on their terms—on their Country, in their cultural space, and with their accompanying identities’ (Lowe et al., Reference Lowe, Bub-Connor and Ball2019a). This may help to balance this power dynamic and engage students and families with school (Ratcliffe and Boughton, Reference Ratcliffe and Boughton2019).

The persistent challenge of attracting and retaining the best teachers for rural schools continues to impact educational opportunities (Halsey, Reference Halsey2017). The persistent belief that the country as a good place to ‘start’ but not ‘devote’ a career in teaching contributes to a high turnover of staff that impacts negatively on developing long-term relationships with students and families (Halsey, Reference Halsey2017). The impact of negative perceptions of teachers about their children and their failure to engage students in learning is intimately linked to the perceived commitment of the school and its relationship with the wider community (Lowe, Reference Lowe2017).

Regionality

Geography remains a critical factor in shaping student aspirations, attainment and choice (Parker et al., Reference Parker, Jerrim, Anders and Astell-Burt2016). The Bradley Review of Australian Higher Education demonstrated students of Aboriginal ethnicity, low socio-economic status and rural areas are the most disadvantaged groups in higher education (Bradley et al., Reference Bradley, Noonan, Nugent and Scales2008). Two-thirds of Aboriginal Australians live in inner regional to very remote areas (ABS, 2018a) and there remains great socioeconomic disadvantage experienced by Aboriginal Australians (AIHW, 2019). It is unsurprising that the Behrendt review (Behrendt et al., Reference Behrendt, Larkin, Griew and Kelly2012) also found poorer higher education participation and completion rates for Aboriginal Australian students.

The impact of differing extents of rurality on educational aspirations of Aboriginal students remains to be determined. Parks et al. (Reference Parks, McRae-Williams and Tedmanson2015) explored the dreams and aspirations of Aboriginal youth transitioning between urban, regional and remote communities. They deemed ambiguity about future plans did not indicate a lack of aspiration but rather a problem of disadvantage and disengagement (Parks et al., Reference Parks, McRae-Williams and Tedmanson2015).

Several studies have evaluated the link between urban Aboriginal Australians and educational success with mixed findings. Studies in these populations have debated the relationship between retention to year 12 and school attendance (Briggs, Reference Briggs2017; Baxter and Meyers, Reference Baxter and Meyers2019), but little is known regarding how aspirations may differ with geography. Briggs (Reference Briggs2017) demonstrated a need to provide alternative pathways such as TAFE to disengaged students. Currently, non-metropolitan vocational education and training participation rates are comparable with urban rates and Certificate 3 completion rates exceed urban completion rates (Halsey, Reference Halsey2017). Aboriginal young people can favour the TAFE pathway for its perceived work opportunities and its practical training pathway (Gore et al., Reference Gore, Patfield, Fray, Holmes, Gruppetta, Lloyd, Smith and Heath2017a).

Nelson and Hay (Reference Nelson and Hay2010) explored the transition from primary to secondary school in an urban Aboriginal population and found ‘complex and multifarious lived experiences’ of the students. They challenged traditional educational pathways and trajectories in order to celebrate the cultural wealth of young people and support transition across varied vocational pathways (Nelson and Hay, Reference Nelson and Hay2010).

Most research regarding the educational experience of Aboriginal students is within the remote Australian context. This may be because remote Aboriginal Australians are likely to be disadvantaged by all three factors outlined in the Bradley Review, namely Aboriginality, low socio-economic status and rural and remote residence (Bradley et al., Reference Bradley, Noonan, Nugent and Scales2008).

The need to reconsider what constitutes ‘educational success’ in remote communities is well documented (e.g. Osborne and Guenther, Reference Osborne and Guenther2013; Guenther et al., Reference Guenther, Disbray, Benveniste and Osborne2017). Remote communities discussed the need for education in language and culture to build strong identities for their students (Guenther et al., Reference Guenther, Disbray, Benveniste and Osborne2017). School and system responses need to resonate with remote community expectations and collective community aspirations for their own young people (Hewitson, Reference Hewitson2007; Guenther et al., Reference Guenther, Disbray and Osborne2015, Reference Guenther, Disbray, Benveniste and Osborne2017). Smith et al. (Reference Smith, Bullot, Kerr, Yibarbuk, Olcay and Shalley2018) provided community perspectives to highlight the importance of connection to family, culture and community in remote Australia and the direct impact this has on future pathways into higher education. While these findings may relate to the unique remote community context, it remains to be determined the impact of cultural community expectations and relationships on the educational system in a rural context.

Two quantitative analyses evaluated a Northern Territory study that compared the aspirations and motivations of students in remote and non-remote areas (McInerney, Reference McInerney2012; Herbert et al., Reference Herbert, McInerney, Fasoli, Stephenson and Ford2014). They found that geographical location was not likely to influence outcomes. A recent review presents correlations between remoteness and educational outcome were most likely a result of cultural distance rather than geographical isolation (Guenther et al., Reference Guenther, Lowe, Burgess, Vass and Moodie2019). These authors expose the myth that remoteness alone is a problem to overcome (Guenther et al., Reference Guenther, Lowe, Burgess, Vass and Moodie2019). This article gives voice to the educational lived experience of regional Aboriginal Australians and demonstrates the complex role of rurality in shaping aspirations.

Methodology

This qualitative study used an appreciative enquiry approach with the aim to build a shared understanding of the lived experiences of Aboriginal high school students. The authors chose this approach to challenge the current perception of the Aboriginal student who is disadvantaged as a ‘problem’, and who needs to conform to the Eurocentric educational context to succeed (Guenther et al., Reference Guenther, Disbray, Benveniste and Osborne2017). Instead, recognising their own colour blindness, the authors composed this study looking through the lens of ‘positive presumption’ to recognise the infinite constructive capacity of the individuals within the system (Cooperrider and Whitney, Reference Cooperrider and Whitney2001).

This Inner Regional (ABS, 2018b) South Australian township is situated 450 km from the nearest capital city. There was a two-part ‘discovery’ phase where Aboriginal community Elders, families and the school faculties were encouraged to give feedback regarding this regional township's educational issues in a colloquial manner. These conversations were presented to the Aboriginal Research Advisory Group to determine questions that would best suit the educational context of the students. The second part of the discovery phase involved listening to the student narrative. Here, as part of the ‘dream’ and ‘design’ phases, students were given the opportunity to envision the best schooling environment and the ‘provocative propositions’ (Cooperrider and Whitney, Reference Cooperrider and Whitney2001) that could achieve this. The deliver/destiny phase involved engaging the complex network of key educational stakeholders. Dialogue between students, their families, current school leadership, the community-controlled Aboriginal health service, Elders, university research academics and local community members was essential. The stories of our students became the focus of the wider community through feedback sessions, social events, presentations and recommendations for local schools.

Recruitment for Aboriginal high school students involved liaising with the local Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Service, two rural high schools and convenience sampling by researchers during a local Close the Gap day event. Regular feedback was sought from the local Aboriginal Research Advisory Group throughout the project. Aboriginal high school students were invited to participate in an initial semi-structured interview to explore their aspirations. Written informed consent was obtained for all participating students and their carers. Semi-structured interviews were between 30 and 60 min in length and conducted on school grounds during normal school hours. A second follow-up interview was offered 4–6 months after the initial interview to all participants, with a view to gain a broader understanding of their school experience over time.

The authors conducted the majority of participant interviews. The interviews were digitally audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim. Transcripts were de-identified and assigned pseudonyms to ensure anonymity. The authors viewed transcripts as a shared creation of understanding between individual school students and the interviewer.

Transcripts were imported to NVivo for coding and analysis. Transcripts were read twice before open coding of relevant content followed by selective coding. These codes were then cross-checked, and initial themes developed before they were reviewed and collated by all authors to reach a consensus. This project attained ethics approvals from the Aboriginal Health Research Ethics Committee (Project number 04-17-745) and the Flinders University Social and Behavioural Research Ethics Committee (Project number OH-00172). Additionally, independent research governance approval was received from the South Australian Department of Education and Childhood Development.

Limitations

This study acknowledges several limitations. Students were recruited by teachers at two local high schools and then self-selected for participation in the study. Self-selected students may not be an accurate representation of students experiencing difficulties at school. This study does not consider the voices of students already disengaged with education and who no longer attend school. Additionally, these interviews occurred during class time and this may have limited students who felt they could not miss class in order to participate. This study was designed to include a follow-up interview for all students to gain a longitudinal view of their schooling experience but there were difficulties scheduling these interviews. This potentially may have impacted on rapport between participants and interviewers as well as the richness of data. Finally, the colour-blindness of researchers who performed and analysed the interviews means that the richness of the diverse contexts of Aboriginal students may not have been adequately explored. The following insights contribute to a growing body of literature however perspectives from other regional Aboriginal communities would be beneficial.

Findings

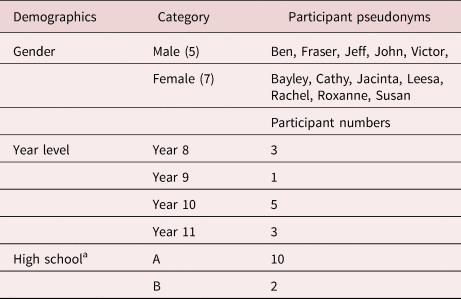

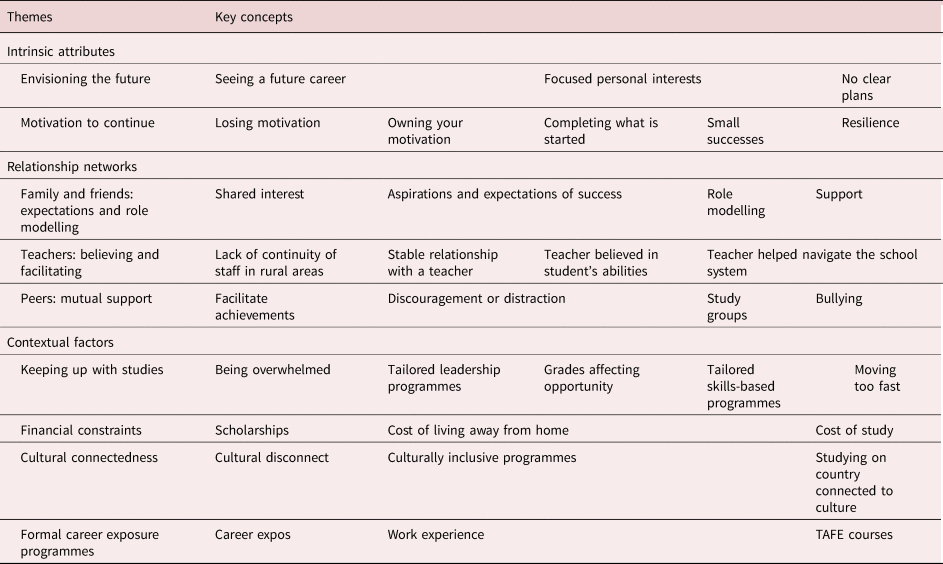

Twelve students who identified as Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander in years 8–11 were recruited into this study. All students were interviewed in 2018, with 12 initial interviews and four follow-up interviews being conducted. Table 1 demonstrates the demographics of the students within the study. Three groups of themes emerged from the interviews: intrinsic attributes, relationship networks and contextual factors. These are outlined in Table 2.

Table 1. Demographics of 12 participating students categorised by gender, year level and school enrolment

a ‘A’ and ‘B’ denote two separate public secondary schools in which participants were enrolled.

Table 2. Research themes and key concepts found in discourses with students

Intrinsic factors: envisioning the future

Student participants described their thoughts of high school and post-secondary school aspirations, with major themes and concepts outlined in Table 2. Within the data, there was a broad range of envisioning experiences: including students who could imagine their future selves in explicit detail and those who had not ever visualised their post-secondary school experience (Table 2). When struggling with a lack of motivation to work on assignments, Jacinta remembered her future career goals to ‘get in the drive again’. She imagined herself ‘working in a classroom, hands on, teaching kids instruments’. Bayley imagined herself being more independent and studying in Adelaide.

Personal interest was the most common reason students had for pursuing a particular pathway after school. Participants who gave a career objective or several potential career aspirations did so on the basis of interest in a given field. Most students had exposure to some activity that cultivated further interest and became an avenue that they could see themselves pursuing in the future. Jeff commented that exposure to the programme Google Sketch Up in primary school helped him to find out he enjoyed creating things. This experience in design influenced his intention to pursue architecture as a career.

Not all high school participants described envisioning their future. Ben said he ‘never thought’ about his plans after high school, despite attending two career expos during his secondary studies. Although his future plans remained unclear, Ben described being determined to complete secondary school.

Intrinsic attributes: motivation to continue

Student participants inferred that strong motivation was needed to achieve success in high school. They commented on losing motivation in relation to academic work. Study participants demonstrated their resilience through articulating a variety of strategies to manage their motivation. For Cathy, confidence gained through small successes played an important role in motivation, ‘grade wise and attendance wise, good year, improved heaps’. Rachel drew on her own personality attributes as a finisher-completer: ‘well it's not exactly what motivates me, it's just that once I start something, I need to complete it…It's just something I've gone by since I started school…The only one who can actually motivate you is yourself’. Ben referred to a self-derived motivation to continue studying and complete year 12 ‘Yeah, I thought [about not finishing], but I do want to finish school…I want to finish school because I just want to’.

Relationship networks: family and friends expectations and role modelling

Most student participants described family members and friends who were already in the career fields they desired. Ben had no other family members who went to university and his elder sister did not finish high school. He referred to an intrinsic motivation to continue studying and complete year 12, however he had not developed clear plans for his future after Year 12. Jeff described an example of shared interest influencing him, ‘My dad used to do a trade for an electrician…Dad used to always kind of teach me stuff…I don't know heaps and I don't know that much at all, but I like to do what he does’.

Some students expressed that having a supportive family member was enough to help them realise their goals to attend university. Leesa was influenced by a grandmother's personal attributes rather than her career—‘I think, with caring—how she works to care for herself and us and I just want to work as hard as her, I guess’. She described talking to family and friends was helpful because ‘you can get like, their perspectives on what you want to do’. Some students were motivated to study to make a positive contribution to their family circumstances. Leesa wanted to study more ‘so, then I can help her [nan] when I'm older and like, help other family members like my mum or my sisters or my brother’. She saw herself as a critical member of the family unit for their future development.

Family and friends acted as role models, which provided participants with access to career insights and pathways. Fraser commented on the support from his brother, currently working in the Western Australian mines, as giving him direction after completing school. Although mining was not his final career objective, he reported this opportunity broadened his post school plans. Rachel drew on a wide variety of social influences to inform her decision to pursue teaching. Her father did not finish school and wanted better for her. He helped to motivate her by reminding her to continue studying so she can fulfil her dreams. Additionally, she helped her younger brother with his own learning difficulties, and this formed her personal drive to help others achieve. Rachel also reported that she felt comfortable to seek support from a grandfather who went to university and her boyfriend's mother who pursued further education after high school. She also had the opportunity to volunteer at a younger sibling's primary school. These relationship networks provided both skills and confidence in pursuing her dream career.

Relationship networks: teachers believing and facilitating

Every student reflected on relationships with teachers being integral to their secondary school experience. Students reported drawing on relationships for extra motivation, feedback on career aspirations and academic support. Leesa described the frequent redistribution of teachers in her rural school as a barrier for her high school performance in subjects, ‘Each teacher is different and it's kind of weird when you have one teacher…and then you go to the same class, but there's a different teacher…you have to adapt to that’. She realised the difficulty of changing teachers meant she had to adapt her current learning strategies, ‘so I guess that's another thing, to ask your teacher for as much help as you can, while they're there. And not put it off’.

Stable relationships with teachers enabled time to develop trust and gain support for current schooling and future aspirations. Jacinta described how a supportive teacher was influential in her transition into high school, ‘she [the teacher] was trying to get us to standard and believed in us’. Students discussed teachers that were flexible and understood the academic burdens of school were important in influencing their experience in school. Jacinta valued the teacher's ability to tailor programmes to support students to effectively manage their volume of work. Jeff mentioned the role teachers played in helping him remain focused, ‘without them…I'd just be mucking around a lot’. Another student noted how the collaborative approach of teachers and the school administration played a crucial role in her academic experience. The staff were essential in helping her obtain a scholarship for tutoring support provided by a city-based university. The school informed her about tuition support opportunities, helped her put together an application and provided a referee. Students also described experiencing pressure from teachers. Rachel and Fraser described occasions where the high volume of work with minimal support from teachers was detrimental to their ability to keep up with their work.

Relationship networks: peer mutual support

All students mentioned relationships with other students influencing their current academic experience. Victor, who openly did not like school, explained that besides his peers ‘there's nothing that I could think of that would get me to school’. His friends were especially influential as he discussed the difficulties he had in motivating himself to attend school. Other students found their peers to be essential to their academic success. A few students attended homework clubs with their friends or formed their own study groups. Leesa described the advantage of having an encouraging group of friends that supported each other with assignment deadlines, ‘If they know they've got to do something, they will tell me. So I guess it kind of gives me a leg up’. Jacinta mentioned the support of her peers in her efforts to excel in school, ‘We all work together to try and get the good grades to get into the better classes later on’.

Several students also reported that relationships at school can be more difficult to navigate. Rachel had a strong desire to pursue teaching but described that her friends were disinterested in learning and thought her career choice would not be interesting. She described the negative impact that managing relationship conflict can have on studies at school. She and Roxanne both mentioned taking problems back into the classroom and commented on how this affected their concentration. However, Rachel demonstrated her resilience to this relationship conflict, ‘Girls can be bitchy but I'm used to that… I am quite assertive with my communication and will tell someone if I don't think something is right’. Two students reported bullying as a major challenge at school. One participant noted that bullying limited their access to services, ‘There is a lot of people here that offered [extra help], but I just feel embarrassed to get some help, because I get bullied’.

Every student commented on the important network of relationships that are constantly influencing their success at school. Family, peers, teachers and other academic staff were critical in the lives of these students.

Contextual factors: keeping up with studies

Curriculum workload was a focus for most interviewed students. Poor grades were recognised as a key barrier to fulfilling career aspirations. Jacinta, in year 8, discussed worrying about current grades, as she perceived her grades in early high school that affected her ability to get into better classes in subsequent years. Several students commented on the large volume of work as a stressor during their studies. Fraser stated the curriculum was

‘just moving way too fast, because they were just throwing things at us…they'll give you a task, next minute you're halfway through it and they're giving you another task on top of that, so you've got to finish that before’.

Leesa described being overwhelmed, ‘Eventually you just stop, kind of like on the goals, and just focus on your schoolwork, because it's too much’.

Participants generally described extracurricular programmes were of great benefit to their confidence, communication skills and academic success. Several participants mentioned the Youth Opportunities Programme, a 10-week skills-based programme for all high school students which centred on themes such as goal setting and leadership. Some students mentioned the activities in this programme were important in helping them succeed in school. Rachel described that the programme changed her worldview, teaching her the importance of staying focused on long-term goals. She described the group sessions, coupled with one-on-one interviews, enabled tailoring of the content, ‘I guess everyone went in there for different reasons, but we all learnt the same things…They give you more information on that skill to the one person that needs it’. Both Fraser and Rachel mentioned fearing the initial burden of missing extra classes while attending the Youth Opportunities programme. However, after the workshop, both students felt adequately supported by teachers to keep up. This reinforces the importance of supportive teachers working in collaboration with a student's expanding skill set. Rachel commented, ‘they taught you the skills to be able to communicate with your teachers effectively’.

Contextual factors: financial constraints

Several students specifically mentioned the role rurality played in their career aspirations. Reduced access to work experience, further education or extracurricular activities was discussed. One student mentioned that there were not enough placements for preferred work experience in nursing due to insufficient resources at the town's only regional hospital.

Roxanne and Jacinta explicitly identified cost as a major barrier to pursuing further study. Jacinta was forward planning. She described saving money for university to address the financial barrier, despite only being in year 8 at the time, ‘It's really expensive and there's no guarantee that you can get scholarships…so I thought if I start now, it [saving] would make it easier for the long run’. When prompted about her biggest challenges in attending university, Rachel responded ‘money for university and how I would get there’.

Contextual factors: cultural connectedness

Cultural connectedness was important for participants when considering their plans after school. Fraser mentioned kinship connections to a mining location that helped him feel like he could work easily after finishing school, ‘since I'm Aboriginal—because our mob pretty much owns the land there, so we're pretty much working [there]’. Other students acknowledged that travelling away to go to university were significant factors in determining their future direction. These students referenced extended distance to family as a key source of anticipated stress, although they were hopeful in their capacity to manage that. Bayley said, ‘I reckon it would be hard [to move away from my family] but I could always come down and see them’.

Some participants reported that cultural connectedness was enhanced through school programmes. Several students described the South Australian Aboriginal Sports Training Academy (SAASTA) programme. SAASTA provides mentorship and key teaching on South Australian Certificate of Education (SACE) accredited subjects. This originally urban initiative was recently introduced to these regional high schools. This cultural programme reportedly improved participants' grades, gave them support, encouraged help-seeking behaviours and strengthened relationships with others and culture. For example, Cathy attributed much of her academic success this year to the programme.

‘Well I never used to get all my work done and stuff, so failing a lot of stuff. And when I got into that, it just got me into the work, got me switched on to what I wanted to do.’

Bayley noted ‘I've learnt new things, especially about my culture…so I like that a lot’.

Contextual factors: formal career exposure activities

Many students attended career expos in the regional area to learn about future tertiary options. For students who already had potential plans, career expos which showcased job opportunities and training pathways were particularly useful. However, for students who were unsure about future pathways, the expos were not described as being useful in clarifying what they wanted to do.

Work experience did not feature strongly in student interviews, although Ben stated, ‘It did help, if I wanted a job like that’. Several of the students in the later years of secondary school described a positive experience with TAFE programmes and associated work experience. Some students reported their TAFE course and work experience programmes were practical and ‘helpful’ in motivating them to pursue further studies in the field. Roxanne stated, ‘I'm doing aged care at the moment so that's another step forward to me becoming a nurse’. Regarding his motivation to do nursing once finishing school, Fraser noted that ‘I had a little sample [of nursing], I did some courses at TAFE’. Some participants were interested in pursuing both TAFE and university education in the future.

Discussion

The student responses provide insight into how intrinsic attributes, relationship networks and contextual factors can widen or narrow a student's ‘aspiration window’. Additionally, their responses lead to a discussion on how rurality influences these contributing factors.

Intrinsic attributes

When students were able to identify with their future academic goals, they reported increased motivation and grades at school. They told stories of envisioning themselves in a career or studying at a university to help them when school became difficult. It is known that positive levels of academic self-concept and school aspiration are correlated with lower levels of academic disengagement (Bodkin-Andrews et al., Reference Bodkin-Andrews, Dillon and Craven2010). Additionally, all students who discussed future aspirations had some level of exposure to this career. Many students discussed exposure through workshops or family members made it easier to identify with that career. Exposure to career options may work synergistically with academic self-concept, whereby identifying with a career may improve academic motivation and this consequently allows students to realise their future goals. This may be particularly difficult to achieve in a rural context as many contextual factors limit exposure to career opportunities.

Oliver and Exell (Reference Oliver and Exell2019) demonstrated self-identification as an Aboriginal person supported the development of a positive self-identity and contributed to the successful transition of students into the workplace. Students demonstrated that experiences of cultural connectedness, through experiences such as SAASTA, improved their grades and their motivation. All students, despite varying abilities to identify with a future profession, demonstrated a degree of self-awareness and reported what they knew of ‘success’ at school. They spoke about the importance of motivation, attendance, focus, self-awareness, resilience and seeking supportive relationships to succeed during and after school.

Further research is needed to understand how rurality impacts an Aboriginal student's ability to imagine themselves in their future careers.

Relationship networks

Teachers

Every student reflected on relationships with teachers as being integral to their secondary school experience. Culturally inclusive teachers are able to establish a deeper contextual understanding about students and their aspirations (Lowe et al., Reference Lowe, Bub-Connor and Ball2019a). This relationship is complex and essential in the context of the rural educator workforce. Rural schools are harder to staff, have higher staff turnover rates and increasingly transient teachers (Halsey, Reference Halsey2017; Downes and Roberts, Reference Downes and Roberts2018). Educational resilience in the classroom is supported by culturally inclusive teachers (Lowe et al., Reference Lowe, Bub-Connor and Ball2019a). Our students reported the lack of continuity in their educators impacted on their studies. They reported belief in student abilities and flexibility was essential in helping them deal with the transient workforce issues. Students ‘pick up’ direct and indirect messages about their worth and their ability to learn and be successful (Halsey, Reference Halsey2017). They look to teachers who do and say things to create a sense of hopefulness and hopefulness ‘is at the heart of building and nurturing students' aspirations and expectations’ (Halsey, Reference Halsey2017). Contextual and culturally responsive teachers engaging in self-reflexivity develop the flexibility that students in our study desired (Halsey, Reference Halsey2017).

Students also reflected on the influence teachers had on their negative schooling experiences. Students underestimated by their teachers are more likely to experience test anxiety, have a lower academic self-concept and have a lower expectancy for success (Urhahne et al., Reference Urhahne, Chao, Florineth, Luttenberger and Paechter2011). Students reported that pressure from teachers made them feel less likely to achieve and repeatedly discussed the difficulties in keeping up with their workload. Rural schools themselves have felt pressure to keep up with the content of the National Curriculum (Halsey, Reference Halsey2017). Especially in remote communities with multi-year classes, presenting the high volume of content was ‘complex and often unmanageable’ (Halsey, Reference Halsey2017). Previous changes to the curriculum have been made in response to schools advocating the increasingly important need for flexibility in jurisdictions with large Aboriginal populations in regional and remote locations (Halsey, Reference Halsey2017). Teachers are essential both face-to-face in the classroom and also in the broader development of the contextually relevant educational reform.

Family

Connection to family remained an important theme in the rural context. Similar to the literature, students often reported the importance of support from family as essential to both forming and supporting educational aspirations. Students are influenced by Aboriginal family members or friends who supported their decision to finish school or had themselves progressed into tertiary education (Gore et al., Reference Gore, Patfield, Fray, Holmes, Gruppetta, Lloyd, Smith and Heath2017a; Smith et al., Reference Smith, Bullot, Kerr, Yibarbuk, Olcay and Shalley2018; Patfield et al., Reference Patfield, Gore, Fray and Gruppetta2019). Similar to the results of Patfield et al. (Reference Patfield, Gore, Fray and Gruppetta2019), some students were able to aspire to act similarly to these close relationship role models. However, none of these students reported an expectation for them to follow a ‘set plan’ into higher education (Patfield et al., Reference Patfield, Gore, Fray and Gruppetta2019). The majority of rural Aboriginal students progressing to tertiary education will likely be the first in their families to pursue higher education and therefore lack a family role model upon which to base their experience (Gore et al., Reference Gore, Patfield, Fray, Holmes, Gruppetta, Lloyd, Smith and Heath2017a). These students are more likely to be in a position of disadvantage with no family members available to discuss university life and aspirations (Luzeckyj et al., Reference Luzeckyj, McCann, Graham, King and McCann2017). Our study demonstrated several students who would be first in family to go to university but drew on peers or older friends for educational support.

Patfield et al. (Reference Patfield, Gore, Fray and Gruppetta2019) found that for many students, completing secondary education was an achievement for them, and one not experienced by many of their family members. Rachel discussed how her father did not finish secondary school and was additionally supportive as he wanted better for her. It is important to note that students from ‘low literacy’ families are often doubly disadvantaged (Ratcliffe and Boughton, Reference Ratcliffe and Boughton2019). First, families are unable to model effective literacy and assist in developing literacy skills, and secondly, they find it harder to develop positive relationships with the school (Ratcliffe and Boughton, Reference Ratcliffe and Boughton2019). However, Sheley (Reference Sheley2011) demonstrated ‘low literacy’ Indigenous parents engaged in their child's learning and with aspirations involving tertiary education for their children. The latter appears to be the case in Rachel's story.

Peers

Students told stories of peers impacting their aspirations in positive and negative ways. There is substantial evidence to support the positive impact of peer groups in education participation and attainment (e.g. Bakadorova and Raufelder, Reference Bakadorova and Raufelder2015; Smith et al., Reference Smith, Bullot, Kerr, Yibarbuk, Olcay and Shalley2018). Students reported the support of friends as necessary to their schooling experience, even if the other friends did not reflect similar aspirations. One student discussed how her friends thought her particular career aspirations were boring, but she still felt supported by them in her studies.

These students told stories of how they were able to manage the negative influence of their peers at school. In the literature, peers have been acknowledged to be detrimental at times, particularly as sources of distraction (Smith et al., Reference Smith, Bullot, Kerr, Yibarbuk, Olcay and Shalley2018). This was confirmed by almost all of the students.

Two students reported how bullying outside the classroom made it difficult to concentrate inside the classroom. While bullying is found to be an inhibitor of learning and an issue for all children, bullying perpetration among Aboriginal youth appears to be different (Coffin, Reference Coffin2010). Walker (Reference Walker2019) demonstrated that while friends made school enjoyable, antagonistic peers who demonstrated teasing, bullying and racism were a reason many left school. Both students drew from strong relationships with friends and teachers to navigate this issue. There is a need for additional research in relation to the impact of bullying in remote and rural Aboriginal educational contexts (Smith et al., Reference Smith, Bullot, Kerr, Yibarbuk, Olcay and Shalley2018).

Contextual factors

Financial constraints

Most young people have to leave their rural community if they wish to pursue further education or gain employment (Halsey, Reference Halsey2017). Two students were currently saving for future relocation costs. None of the students demonstrated an understanding of the additional financial support should they wish to pursue further study elsewhere. Multiple scholarship programmes have been implemented to assist with transfer and accommodation costs associated with university attendance (Rahman, Reference Rahman2010; Osborne et al., Reference Osborne, Paige, Hattam, Rigney and Morrison2019). Rahman (Reference Rahman2010) suggested many university scholarships appear restricted to private school students in urban areas and more opportunities need to be implemented for Aboriginal students in the Australian public education system. Fluctuations in funding due to the cyclical political and industrial fortunes of regional areas impact the long-term stability of local educational access programmes (Osborne et al., Reference Osborne, Paige, Hattam, Rigney and Morrison2019). This means that, for regional communities, funding for future academic education must heavily rely on metropolitan university initiative. Our study demonstrates that rural students are considering the financial costs of university early in their studies, but require assistance navigating financial support outside their community.

Cultural connectedness

Distance from culture having greater impact on aspirations than physical remoteness remained a theme in our study (Guenther et al., Reference Guenther, Lowe, Burgess, Vass and Moodie2019). One student noted that having cousins in the city made it significantly easier to envision herself going away to university. Studies have demonstrated synergy between culture, community outcomes, education participation and academic attainment (Smith et al., Reference Smith, Bullot, Kerr, Yibarbuk, Olcay and Shalley2018; Patfield et al., Reference Patfield, Gore, Fray and Gruppetta2019).

Often, the way forward in culturally inclusive programmes is not clearly defined and requires an individual and community needs assessment (Russell, Reference Russell2006; Shay and Heck, Reference Shay and Heck2015). Students reported the culturally inclusive programme SAASTA significantly improved their confidence and success at school. This was originally an urban-based, mixed academic and sports programme that was recently introduced to this township. Munns et al. (Reference Munns, O'Rourke and Bodkin-Andrews2013) demonstrated eight common themes that were indicators of success for culturally inclusive school programmes. The SAASTA programme encompasses indicators 4, 7 and 8—Aboriginal perspectives and values are embedded in the curriculum, targeted support is provided for Aboriginal students, and relationships between teachers and students demonstrates ‘Aboriginal students as important, responsible and able to achieve’ (Munns et al., Reference Munns, O'Rourke and Bodkin-Andrews2013).

It is well documented in remote communities that the school system needs to resonate with remote community expectations and collective community aspirations (Hewitson, Reference Hewitson2007; Guenther et al., Reference Guenther, Disbray and Osborne2015, Reference Guenther, Disbray, Benveniste and Osborne2017). In this rural township where our study took place, most students valued the completion of secondary school and reported similar beliefs within their social groups. It is unlikely that aspirational ambivalence of the students in our study was a result of misalignment of community and cultural values. However, the interactions between school and culture are complex (Lowe et al., Reference Lowe, Harrison, Tennent, Guenther, Vass and Moodie2019b) and more research regarding the educational values of a rural Aboriginal community and how those values affect student aspiration would be beneficial.

Formal career exposure activities

Gore et al. (Reference Gore, Patfield, Fray, Holmes, Gruppetta, Lloyd, Smith and Heath2017a) identified that both a lack of knowledge about career options and a lack of career guidance impeded progression into university for Aboriginal students. It has been demonstrated that having a degree of exposure to and involvement with higher education prior to the completion of secondary school yields a greater connection with higher education (Gore et al., Reference Gore, Patfield, Holmes, Smith, Lloyd, Gruppetta, Weaver and Fray2017b). Two students mentioned the limited resources of their rural community impacting their exposure to a potential career. One student, considering nursing as a career, was unable to secure a work experience position at the local hospital due to limited staffing capabilities. Another student discussed how he undertook work experience at a tyre shop in order to fulfil the requirements of the school programme. He had no intention of pursuing this as a career but there were no other available options for work experience in his chosen interest field.

With the introduction of the HEPPP initiative, many universities have implemented programmes designed to increase the degree of exposure to higher education (e.g. Thomas et al., Reference Thomas, Ellis, Kirkham and Parry2014; Fleming and Grace, Reference Fleming and Grace2015, Reference Fleming and Grace2016; Osborne et al., Reference Osborne, Paige, Hattam, Rigney and Morrison2019). Unfortunately, there is little evidence evaluating the long-term success of these pathways (Guenther et al., Reference Guenther, Lowe, Burgess, Vass and Moodie2019). Traditionally education recruitment has focussed on enrolment numbers as indicators of success (Guenther, Reference Guenther2013) but this gives little insight into the long-term impact of these programmes in cultivating aspiration (Guenther et al., Reference Guenther, Lowe, Burgess, Vass and Moodie2019). Many programmes take the form of metropolitan university visits and career expos to increase university enrolment and attendance (e.g. Gale and Parker, Reference Gale and Parker2013; Irwin et al., Reference Irwin, Callahan and Duroux2015; Fleming and Grace, Reference Fleming and Grace2016). In our study, there were no students who demonstrated knowledge about specific Aboriginal access entry pathways or rural entry pathways, and few had attended career expos. In spite of this, most students had post-secondary school ideas but remained ambivalent regarding their choice. One student reported attending multiple career expos and reflected that they could be a source of stress for students who had ‘no idea’ about their future plans. This poses a question of when, how and why universities should be investing in career expos. Most literature regarding Aboriginal Australians interactions with tertiary education focuses on those already at university (e.g. Parissi et al., Reference Parissi, Hyde and Southwell2016; Trudgett et al., Reference Trudgett, Page and Harrison2016; Taylor et al., Reference Taylor, Lalovic and Thompson2019). Long-term follow-up of secondary students as they progressed to and through university would be beneficial.

Vocational training or TAFE programmes offer additional opportunities beyond high school. The local TAFE offered subject opportunities while students were still in school. Some students found these programmes instrumental in validating their career plans. Prior exposure to a career option in school-based workshops impacted remote student aspirations, even if their conceptions about the actual profession were limited (Senior and Chenhall, Reference Senior and Chenhall2012). Others reported TAFE provided a ‘safety net’ of employable skills while they were still exploring. Similar to Gore et al. (Reference Gore, Patfield, Fray, Holmes, Gruppetta, Lloyd, Smith and Heath2017a) these students reflected favouring the TAFE pathway for its perceived work opportunities and its practical training pathway. Briggs (Reference Briggs2017) found that urban Aboriginal students hold preference for vocational ‘earn as you learn’ training programmes such as TAFE, and this appears to hold true in the rural context. It many rural centres, TAFE education may be more accessible while still in high school and also offers the advantage that students will not need to move to a metropolitan centre to finish their post-secondary school certifications.

Conclusion

This paper is important as it highlights the complex interplay of internal and external factors to the Aboriginal student secondary school completion experience and also demonstrates the changing landscape of Aboriginal students in the literature. This study demonstrates the impact of rurality on the narrow aspiration window that is the reality for some Aboriginal students. The impact of rurality on progression to further educational or vocational career pathways is not defined purely by a geographical or financial burden. Those who have to travel from remote communities to pursue education must also negotiate the challenge of staying connected to their sense of culture, country and family.

This study is important as it has given a voice to students currently within the rural secondary school context and has highlighted a continuum within the Aboriginal academic experience. This study offers a new perspective to discourses surrounding academic disadvantage and highlights the lived experience of students in secondary school. It gives recognition to the academic aspirations of young rural Aboriginal Australians—an area underrepresented in the current literature.

Jessica Howard is a postgraduate medical student at Flinders University in South Australia. Her previous degree was a Bachelor of Clinical Sciences. Her primary research interests include Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health and wellbeing and the preventative medicine landscape.

Jacob Jeffery is a final year postgraduate medical student Flinders University of South Australia with a previous Bachelor of Medical Science. His research interests primarily focus on cultural expression and its intersection with rurality, medicine and community.

Lucie Walters, PhD, is Director of the Adelaide Rural Clinical School at the University of Adelaide. This program provides a full academic year of clinical training to University of Adelaide medical students in their penultimate year. Students are based in small rural communities in the north and west part of rural South Australia where they actively participate in patient care under the supervision of experienced rural doctors in general practice, rural hospitals, community and outpatient settings. Her research interests include work-integrated learning, adult education pedagogies, rural training pathways, and rural generalism in medicine.

Elsa Barton, PhD, is a Research Fellow in the Integrated Mental Health Research Program at the Department of General Practice at the University of Melbourne. Her primary research interest is in health services research and her research seeks to evaluate patient experiences of care. Elsa was previously based in rural South Australia where the focus of her research was on Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health and wellbeing.