Introduction

When clients apply for treatment at a mental health care institution, they usually go through an intake assessment first. During the intake assessment, the therapist asks the client to provide detailed information on current and previous problems, and on factors that potentially maintain or contribute to these problems. The intake assessment can also be used to identify the client’s strengths and resources, although the extent to which strengths and resources are addressed varies between therapists and therapy modalities (Kuyken et al., Reference Kuyken, Padesky and Dudley2009; Meyer and Melchert, Reference Meyer and Melchert2011). Solution-focused approaches even question the need for extensive knowledge about problems (de Shazer et al., Reference de Shazer, Dolan, Korman, Trepper, McCollum and Berg2021). Instead, they emphasize the need to get a detailed image of the client’s preferred future, and to identify problem-free areas and strengths that can be used as stepping stones on the path towards that future.

Frequently, the intake assessment provides the therapist with the first impression of a client. Cognitive processes such as the anchoring effect predict that first impressions disproportionately influence decisions over time (Furnham and Boo, Reference Furnham and Boo2011). To illustrate the effects of anchoring, recent research found that first impressions were slow to update and were overly influential in determining managers’ decisions on whom to promote six years later, compared with subsequent indicators of performance (Black and Vance, Reference Black and Vance2021). We could not identify research on the impact of first impressions in clinical practice. Nevertheless, given that first impressions can have such a strong and lasting emotional impact, the intake assessment is likely to influence therapists emotionally, with a potential impact also on their decision-making, therapeutic optimism, and potentially even therapeutic effectiveness.

The Broaden-and-Build theory predicts that positive emotions help individuals to come up with a wider range of ‘thought–action repertoires’ (i.e. a wider array of ideas for potentially helpful approaches, interventions or reactions to treatment obstacles; Fredrickson, Reference Fredrickson2001). Therefore, if therapists are able to take a strengths-based view and cultivate positive emotions during the intake assessment and in the early sessions of treatment, this may help both the client and the therapist to increase their sense of possible actions that can be taken to help the client. Supporting this notion, a naturalistic treatment study found that higher levels of therapist hope positively predicted clients’ treatment outcomes (Coppock et al., Reference Coppock, Owen, Zagarskas and Schmidt2010).

The main aim of the current study is to provide a first step towards examining the impact that information collected during intake assessments may have on therapists’ emotions and on their expectations for successfully working with a client. Trainee therapists were asked to read several vignettes that presented client information in either a problem- or a solution-focused way and to rate their emotions and expectations after each vignette. Compared with problem-focused vignettes, we expected solution-focused vignettes to be associated with (i) higher positive emotions, (ii) lower negative emotions, and (iii) higher positive expectations. Enabling direct replication, the study was executed in two samples of students undergoing therapy training, one in the Netherlands (Sample 1), and one in the United Kingdom (Sample 2).

Method

Study design and statistical analysis

The current study employed a within-subject experimental design with condition (solution-focus vs problem-focus) as independent variable. Outcome variables (positive emotions, negative emotions, and positive expectations related to working with a client) were averaged per participant per condition. Then, the effect of condition was examined through paired t-tests contrasting the effects of solution- versus problem-focused vignettes. Analyses were run separately for each sample. Power analysis indicated a required sample size of 30 participants to identify medium effect sizes with a power of 0.9 and an alpha error probability of 0.05, assuming a moderate correlation in-between measurements.

Procedure

Ethical committees of Maastricht University and University of Exeter both approved the study (reference numbers 177_04_03_2017 and eCLESPsy000217, respectively). The study was preregistered on aspredicted.org (see https://aspredicted.org/zt9yb.pdf ). Participants were psychology or mental health students who had completed at least one clinical skills course (Sample 1, the Netherlands), or fourth-year undergraduates in training to become psychological wellbeing practitioners (all currently enrolled in clinical placements in Improving Access to Psychological Therapy (IAPT) settings; Sample 2, UK).

Potential participants were invited to take part in this online study through email. In order to avoid response-bias, a cover story informed participants that the goal of the study was to assess trait mindfulness and its impact on participants’ ratings of client vignettes. Trait mindfulness was chosen because it provided a rationale for the study without inducing scrutiny towards the systematic differences in case descriptions, as for example cover stories on critical thinking styles or cognitive biases may have done. Participants were not informed that there were two types of vignettes (i.e. solution- vs problem-focused).

After providing informed consent in Qualtrics, participants completed demographic questions and a mindfulness questionnaire (to keep up the cover story). Then, four vignettes were presented one by one. Participants were asked to read each vignette attentively. After each vignette, participants rated their current affective state and their expectations for working with that client; see ‘Measures’ section below. To prevent order effects, we ensured that the order of the four vignettes was fully counterbalanced. After completing the study, participants received a debriefing form and received a gift voucher worth 5EUR or 5GBP, depending on their location (the Netherlands or UK).

Case descriptions

A series of short vignettes (range 519 to 660 words) described four imaginary clients with mood disorders (two men, two women). A solution-focused and a problem-focused version were created for each client, resulting in eight vignettes. Participants each rated four vignettes, one for each client; two of the four vignettes had a solution-focus, the other two vignettes had a problem-focus.

The solution-focused vignettes provided short background information on the problem and then proceeded to describe (i) how clients envisaged their lives after successful therapy, (ii) what current exceptions to problems were (i.e. things that were still going relatively well and moments when clients’ mood was just a little bit better), and (iii) first signs of improvement (i.e. how clients would recognize that they were starting to feel better).

The problem-focused vignettes provided an overview of current complaints and their development (including potential triggers and recent life events, maintaining factors and clients’ reason for seeking help), described family of origin and formative experiences, and mentioned relevant medical history and earlier mental health diagnoses, if any. For examples of problem- and solution-focused vignettes, see the extended report (available online in Supplementary material).

Measures

After each vignette, participants rated their current affective state and their expectations for working with the client on several 0–100 mm visual analogue scales with anchors 0 (not at all) to 100 (very much). Positive affect was calculated as the average of the variables cheerful, content, hopeful and enthusiastic (Cronbach’s alpha .880). Negative affect was calculated as the average of the variables anxious, frustrated and sad (Cronbach’s alpha .667). Positive expectations for working with a client were calculated as the average of four variables such as ‘How confident are you that you can help this client get his/her life back on track?’ (Cronbach’s alpha .912).

Results

Thirty-three participants in Sample 1 and 29 participants in Sample 2 completed the study. In Sample 1, 33.3% had some form of experience working with clients with mental health problems in practice (through internships, voluntary work, or paid work). In Sample 2, all participants had some experience working with clients. Participants in both samples reported finding the case descriptions highly believable (82.58 and 82.75 out of 100, respectively). Participants rated their ability to imagine themselves as the clients’ therapists as moderate to high (64 out of 100; Sample 1), or high (80 out of 100; Sample 2), in line with participants in Sample 2 being more experienced in working with clients, compared with participants in Sample 1.

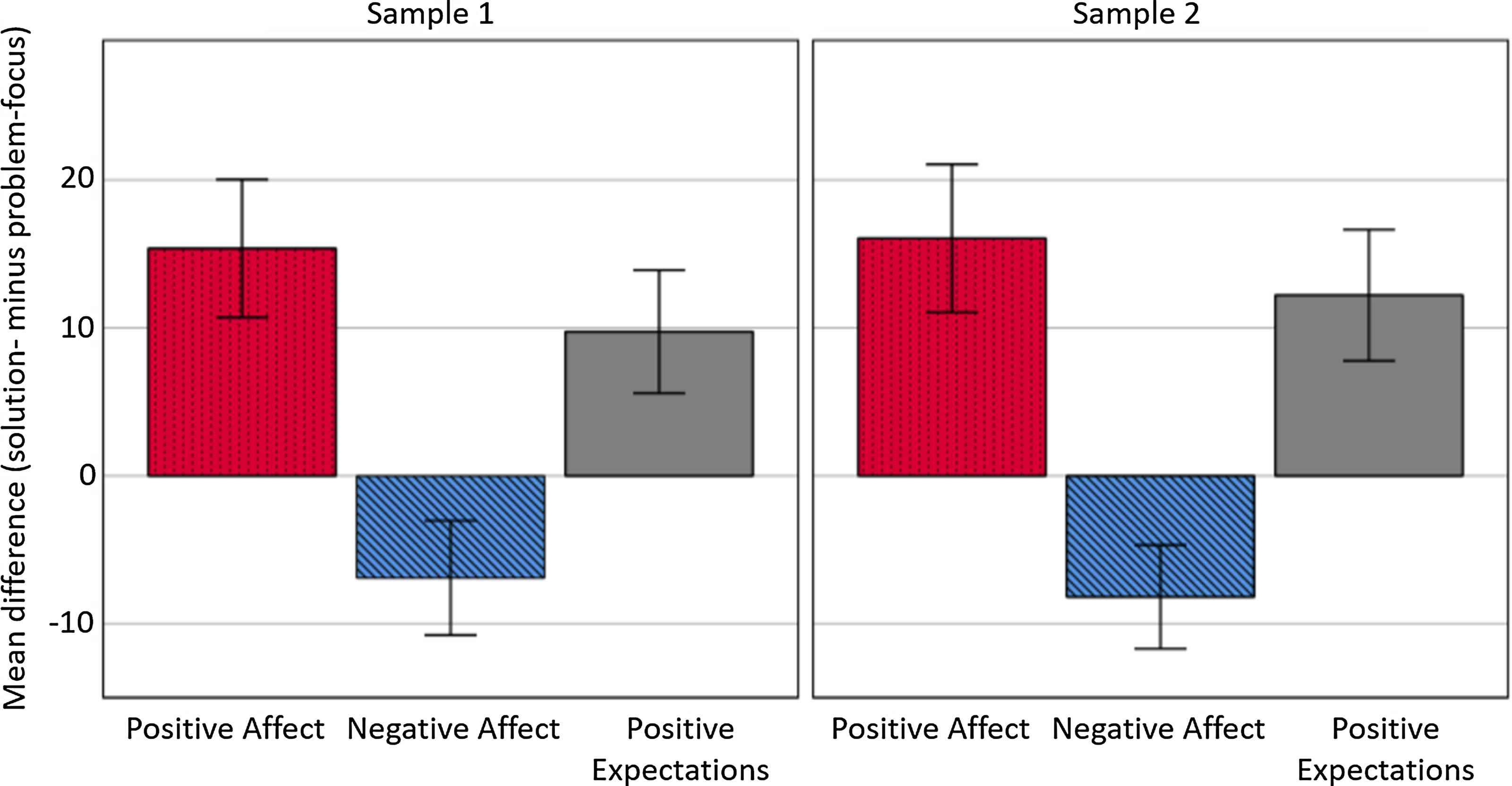

In both samples, participants experienced significantly more positive affect (Sample 1: t = 6.71; Sample 2: t = 6.58; both p < .001) and significantly less negative affect (Sample 1: t = –3.03; Sample 2: t = –4.78; both p < .001), after solution-focused compared with problem-focused vignettes. In addition, expectations for successful treatment were significantly more positive (Sample 1: t = 4.77; Sample 2: t = 6.64; both p < .001). Effect sizes were large (Cohen’s d > .8) for all outcomes except for negative affect in Sample 1 (d = .6; medium). Figure 1 illustrates the differences between conditions.

Figure 1. Mean differences between solution-focused and problem-focused vignettes. Outcome variables were measured on a scale of 0 to 100. Error bars represent 95% confidence intervals. Positive values reflect higher ratings for solution- relative to problem-focused vignettes; negative values denote reflect lower ratings for solution- relative to problem-focused vignettes.

Discussion

The aim of the current vignette study was to compare the effects of solution-focused and problem-focused case descriptions on therapists’ emotions and therapeutic optimism in a within-subject comparison. Outcome variables were positive affect, negative affect, and therapists’ expectations for successful treatment.

In both samples, the results supported our pre-registered hypotheses. After reading solution-focused vignettes, participants reported significantly higher positive affect and significantly lower negative affect, in addition to having significantly higher positive expectations for successful treatment, compared with after reading problem-focused vignettes. Effect sizes were generally large.

To our best knowledge, this study is the first study to experimentally investigate the effect of solution- versus problem-focused case descriptions on therapists’ emotions. Where our study links solution- and strengths-focused case descriptions to higher positive emotions and expectancies for treatment in therapists, previous studies have reported beneficial effects of solution-focused questions on positive emotions in clients.

Results suggest that gathering detailed information about clients’ preferred future, their strengths, and exceptions to problems (moments during which the problem is absent or less pronounced, or moments during which they can cope better) may help therapists to feel more positive about chances of successfully collaborating with clients. Taking a strengths-based view and cultivating positive affect may therefore help to preserve mental well-being and to prevent burn-out in therapists. Given that a previous study found that therapists’ hope for treatment positively predicted treatment outcomes (Coppock et al., Reference Coppock, Owen, Zagarskas and Schmidt2010), clients too may benefit from therapists feeling more positive.

Strengths of the study include the within-subject design and the high degree of control achieved through carefully matching the content of descriptions and counterbalancing the order of vignettes. In addition, we directly replicated the results in two different samples.

Limitations include the following. First, the current study used students with clinical training as participants, instead of fully qualified therapists. Second, no ‘blended’ vignettes were included (i.e. vignettes with an equal balance on problem- and solution-focused information). Third, the results of the current vignette provide only a short-term snapshot of the impact of first impressions on trainee therapists’ emotional experience that cannot be directly linked to long-term mental health outcomes or to treatment success. Nevertheless, even though we could not identify research on the impact of first impressions in clinical practice, research in other fields indicates that first impressions are slow to update and can have a lasting and overly influential impact on later decision-making (Black and Vance, Reference Black and Vance2021). Fourth, we did not explicitly check whether participants saw through the façade and realized the true purpose of the study.

Suggestions for future research include the following. First, findings should be replicated in fully trained therapists. Second, to make inclusion of positive information more relevant to institutions providing problem-focused treatments, studies should compare solution- and problem-focused intake approaches to ‘blended’ intake formats, in which a problem-focus is amplified with information on strengths and better moments. Third, future studies should systematically compare the effects of solution- and problem-focused intake assessments in real-life clinical settings, investigating the effects of these intake assessments on clients’ and therapists’ levels of hope, optimism and well-being, and on long-term clinical outcomes. Fourth, future research could investigate how client characteristics (e.g. ethnicity, socio-economic status, relationship problems, or type of diagnosis) influence therapists’ biases.

In conclusion, the current study suggests that providing information about clients’ strengths and problem-free areas may help to increase therapists’ positive emotions and their expectations for successful treatment. Examples of information that may be useful to include during intake assessments are clients’ strengths, exceptions to problems, and positively formulated goals that provide a detailed image of how clients see their life after successful therapy.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S135246582300022X

Data availability statement

Upon publication, the anonymised dataset will become available for use upon request in Dataverse.

Acknowledgements

With sincere thanks to Katriona Campbell, Lisa Cappelletti, Emily Widnall and Alice Price for their help with study set-up and/or data collection.

Author contribution

Nicole Geschwind: Conceptualization (equal), Data curation (equal), Formal analysis (lead), Investigation (equal), Methodology (equal), Project administration (equal), Writing – original draft (lead), Writing – review & editing (equal); Barnaby Dunn: Conceptualization (equal), Data curation (equal), Investigation (equal), Methodology (equal), Project administration (equal), Writing – original draft (supporting), Writing – review & editing (equal).

Financial support

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests

The authors declare none.

Ethical standard

The authors have abided by the Ethical Principles of Psychologists and Code of Conduct as set out by the BABCP and BPS. Ethical committees of Maastricht University and University of Exeter both approved the study (reference numbers ERCPN_177_04_03_2017 and eCLESPsy000217, respectively). Any necessary informed consent to participate/for the results to be published has been obtained.

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.