Introduction

Worry is a chain of thoughts and images, negatively affect-laden and relatively uncontrollable. The worry process represents an attempt to engage in mental problem-solving on an issue whose outcome is uncertain but contains the possibility of one or more negative outcomes. Consequently, worry relates closely to fear process. (Borkovec et al., Reference Borkovec, Robinson, Pruzinsky and DePree1983; p. 9)

It is now almost 40 years since Borkovec and colleagues provided this definition in their seminal paper and so launched the modern psychological study of worry, and by extension generalized anxiety disorder (GAD). Their classic definition has inspired and guided the developments of models and treatments since, and within this definition we can find some of the differences in emphasis between the models as well as the ongoing debates. These include the role of thoughts versus images, the function of worry, the role of affect or emotion, the degree to which worry is controllable, the role of uncertainty, and how worry may relate to fear.

Interestingly, this definition appeared in 1983, soon after the arrival of GAD as a diagnostic category in the third edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-III; American Psychiatric Association, 1980), following the decision to split the DSM-II (American Psychiatric Association, 1968) category of anxiety neurosis into GAD and panic disorder (see Crocq, Reference Crocq2022, for a historical overview). However, worry as a defining feature did not arrive until DSM-III-R (American Psychiatric Association, 1987). DSM-IV (American Psychiatric Association, 1994) reduced the list of associated symptoms, and the definition of GAD was relatively unaffected by DSM-5 (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). Therefore, we have had a reasonably stable definition of GAD with worry as a defining feature for almost 30 years, and now the 11th edition of the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems (ICD-11; World Health Organization, 2022) broadly aligns with DSM-5. Despite definitional and diagnostic stability, our understanding of GAD in psychological terms is far from stable.

Publication trends in GAD research

In 2000, Dugas reviewed research into anxiety disorders in two databases (PsycLIT and MEDLINE) from 1980 (the year of DSM-III and GAD’s introduction) until 1997 and noted that among other anxiety disorders [including obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD)] the proportion of research into GAD had increased in the 1980s but remained low and largely stable up to 1998 and noted the ‘paucity of research into process issues’ (Dugas, Reference Dugas2000; p. 31). In 2010, Dugas and colleagues commented that the trend from 1998 to 2008 had continued the increase in numbers of articles but that the percentage remained the same at less than 8% each year (Dugas et al., Reference Dugas, Anderson, Deschenes and Donegan2010). Moreover, for GAD ‘publications focused more often on treatment (44%) than on descriptive issues (26%), process issues (22%), and general reviews (8%)’ (Dugas et al., Reference Dugas, Anderson, Deschenes and Donegan2010; p. 781). Boschen (Reference Boschen2008) independently reached similar conclusions about the growth of GAD research from 1980 to 2005 and predicted the number of articles that would be published in 2015 for each disorder based on linear trends up until 2005; he predicted a meagre 56 for GAD. Asmundson and Amundson (2018) followed up these predictions and found more than double the number predicted for GAD. However, this was also the case for OCD and PTSD. The overall pattern of only a small proportion of GAD studies among anxiety research remained the same. In summary, bibliometric data show that 35 years after its inclusion in the diagnostic system, GAD remains under-researched relative to other anxiety disorders including panic disorder (which also made its entry in 1980), with annual research output at less than a third of that into OCD and social anxiety, and about a tenth of that into PTSD.

According to Ruscio et al.’s (Reference Ruscio, Hallion, Lim, Aguilar-Gaxiola, Al-Hamzawi, Alonso, Andrade, Borges, Bromet, Bunting, Caldas de Almeida, Demyttenaere, Florescu, de Girolamo, Gureje, Haro, He, Hinkov, Hu, de Jonge and Scott2017) meta-analysis of representative population surveys across 26 countries (n=147,261), GAD has a moderately high lifetime prevalence (3.7%, SE=0.1%) especially among high income countries (5.0%, SE=0.1%), very high lifetime co-morbidity (81.9%, SE=0.7%), and severe role impairment across life domains for about half (50.6%, SE=1.2%). The corresponding figures for PTSD across 26 countries (n=123,298) using the same methodology (Koenen et al., Reference Koenen, Ratanatharathorn, Bromet, Karam, Stein, Bromet, Karam, Koenen and Stein2018) are similar, namely, moderately high prevalence (3.9%, SE=0.1%) again especially among high income countries (5.0%, SE=0.1%). Direct comparison of severe impairment rates (Kessler et al., Reference Kessler, Chatterji, He, Levinson, Karam, Alonso, Bromet, Karam, Koenen and Stein2018) show similar figures for GAD vs PTSD for close personal relationship functioning at 27.6% (1.5) vs 30.5% (2.7) and for ability to work 26.8% (1.8) vs 21.2% (2.2). Based on prevalence and impairment figures alone, there is no obvious reason why GAD is less worthy of attention and why research output should be only one-tenth that of PTSD.

In a commentary on the Asmundson and Asmundson (Reference Asmundson and Asmundson2018) findings, Newman and Przeworski (Reference Newman and Przeworski2018) suggested that the relative lack of attention to GAD compared with other anxiety disorders may be in part due to the ongoing debate about the accuracy of the diagnostic criteria for GAD, the transdiagnostic nature of GAD symptoms and worry, as well as the misperception of GAD as a disorder that is less serious than others. However, the criteria have now been essentially stable since 1994 and the data do not support that GAD is less serious, so it is perhaps the transdiagnostic nature of worry and GAD symptoms that contribute.

Models of GAD

While the number and proportion of research articles may still lag behind other disorders with a relative paucity of studies of process, there has been a proliferation of models of GAD. Behar et al. (Reference Behar, DiMarco, Hekler, Mohlman and Staples2009) published a much-cited review describing five different models, the main components of the models, the treatments based on them, as well as summaries of the supporting evidence for the model and what treatment evidence existed at that point. These were named the Avoidance Model of Worry and Anxiety (AMW), the Intolerance of Uncertainty Model (IUM), the Metacognitive Model (MCM), the Emotion Dysregulation Model (EDM), and the Acceptance Based Model (ABM). The key references for each of these models can be seen in Table 1. More recent articulations of the models are also included where relevant. Continuing forward from Behar, searches were conducted on 16 May and again on 22 August 2022 in Scopus using the search terms: ((TITLE (model OR theory OR approach OR account)) AND (TITLE (‘gad’ OR worry OR worrying OR ‘generalized anxiety disorder’ OR ‘generalised anxiety disorder’))). The search generated 242 hits. The strategy was first checked to ensure all the models/main sources included in Behar et al. (Reference Behar, DiMarco, Hekler, Mohlman and Staples2009) had been identified. Based on a title-abstract screening, 63 sources making explicit reference to a model or theory were exported as a .CSV file. These were then coded in reference to a specific model (if known) or further investigated (reference list and citation searches) to see whether the source identified was linked to both a formal exposition of the model and a treatment evaluation. Thirty-four sources explicitly referred to one or more of the five models reviewed by Behar, 10 referred to a different model that also had one or more initial treatment evaluations (and have been included in this review), four referred to a model which has not yet been evaluated as a treatment (Berenbaum, Reference Berenbaum2010; Davey, Reference Davey, Davey and Wells2006; Gústavsson et al., Reference Gústavsson, Salkovskis and Sigurðsson2021; Vasey et al., Reference Vasey, Chriki and Toh2017), one proposed and tested a treatment but there was no formal exposition of a model (Kopelman-Ruben et al., Reference Kopelman-Rubin, Omer and Dar2017), one was an integration of two different models, the IUM and the EDM and so would be largely redundant in this review (Ouellet et al., Reference Ouellet, Langlois, Provencher and Gosselin2019), nine were reviews of models or approaches, and four were empirical investigations of various models that were not at the stage of proposing treatment (see Data availability section for details).

Table 1. Models of generalized anxiety disorder and key sources

* Citation count from Google Scholar, 27 May 2022.

The four models that have emerged (see Table 1) have been named in line with Behar’s nomenclature: the Contrast Avoidance Model (CAM; Newman and Llera, Reference Newman and Llera2011), the Emotion Focused Model (EFM; Murphy et al., Reference Murphy, Rowell, McQuaid, Timulak, O'Flynn and McElvaney2017), the Cognitive Model of Worry (CMW; Hirsch and Mathews, Reference Hirsch and Mathews2012), and the Three Phase Model (TPM; Chigwedere and Moran, Reference Chigwedere and Moran2022). Note, the focus of this review is not the relative merits of any specific model, but how the models may collectively inform us about the nature and status of model-driven GAD research. The number of citations of the most cited of the early sources about the model is used as a proxy indicator of both longevity and relative influence to date. The mean citations per year standardizes them to a degree, but citations tend to build in an upward curvilinear manner, so recent publications are still relatively penalized in this metric compared with those published a decade or more before.

The inclusion of the later models is based on (i) at least one articulation of the model, and (ii) at least one evaluation of the treatment leading from it. Other models were considered, but do not yet have treatments based upon them. An interesting exclusion is Woody and Rachman’s (Reference Woody and Rachman1994) analysis of worry as an unsuccessful search for safety. This early account does not seem to have led directly to specific models or treatments, although alongside astute observations of the presentation of GAD the article mentions over-estimation of threat, absence or loss of safety (including early loss or uncertainty about caregivers), responsibility, interpersonal safety, etc. Furthermore, they commented on the lack of specific procedures for treating GAD at that time and proposed that building safety may be the way forward, while acknowledging that there was no guaranteed or standardized way to do that given the idiosyncratic nature of both threats and the loss of safety. Other exclusions are the Mood-as-Input Model (Davey, Reference Davey, Davey and Wells2006), the Initiation-Termination Model of Worry (Berenbaum, Reference Berenbaum2010), a combination of narrative therapy and acceptance and commitment therapy addressing positive beliefs about worry (Kopelman-Ruben et al., Reference Kopelman-Rubin, Omer and Dar2017), a model based on cognitive control capacity (Vasey et al., Reference Vasey, Chriki and Toh2017), and the recent responsibility and safety-seeking account by Gústavsson et al. (Reference Gústavsson, Salkovskis and Sigurðsson2021).

Components of models

Inspired by Behar et al. (Reference Behar, DiMarco, Hekler, Mohlman and Staples2009), the key elements of each model, as described by the authors, including the original sources for each and later updates, were extracted as short phrases of approximately three to six words (n=92). The lists were iteratively coded into categories and the categories then grouped under topic headings resulting in 42 elements in 14 categories. The topic headings were ordered for presentation purposes. The summary of this coding can be seen in Table 2 below; see Data availability section. As can be seen in Table 2, the number of components varied from seven to 14. The three-emotion based models had the fewest components (EDM, ABM, EFM), the more recent cognitive and avoidance models had the most (CAM, CMW, TPM), and the initial avoidance and cognitive models lay in between (AMW, IUM, MCM). The extraction and coding is somewhat arbitrary although based on careful reading of the original sources and recent articulations. Consequently, the coding may not reflect the original authors’ ideas as to what is central to the model, or secondary. However, even given some differences in coding, it is the overall patterns across the models that is important to the argument in the initial part of this article, not any specific feature. The specific features become more important in the latter part of this article.

Table 2. Features of each model according to category

AMW, Avoidance Model of Worry; IUM, Intolerance of Uncertainty Model; MCM, Metacognitive Model; EDM, Emotion Dysregulation Model; ABM, Acceptance-Based Model; CAM, Contrast Avoidance Model; EFM, Emotion Focused Model; CMW, Cognitive Model of Worry; TPM, Three Phase Model. Unique features are in bold type.

Similarity between models

Based on the coding in Table 2, it is possible to construct a similarity matrix between the models (see Table 3). As can be seen in Table 3, the MCM and the CAM show no similarity, nor do the CAW and the CMW. All other pairs have some degree of similarity, with the highest similarity between the MCM and the CMW, although each have features unique or almost unique to the model (see Table 2). Some similarities (e.g. the inclusion of a trigger) are probably less consequential than others (e.g. positive beliefs about worry).

Table 3. Similarity matrix for models of GAD showing number of overlapping features

AMW, Avoidance Model of Worry; IUM, Intolerance of Uncertainty Model; MCM, Metacognitive Model; EDM, Emotion Dysregulation Model; ABM, Acceptance-Based Model; CAM, Contrast Avoidance Model; EFM, Emotion Focused Model; CMW, Cognitive Model of Worry; TPM, Three Phase Model. Green represents low relative overlap (0–2), amber moderate (3–4), and red high (5–6).

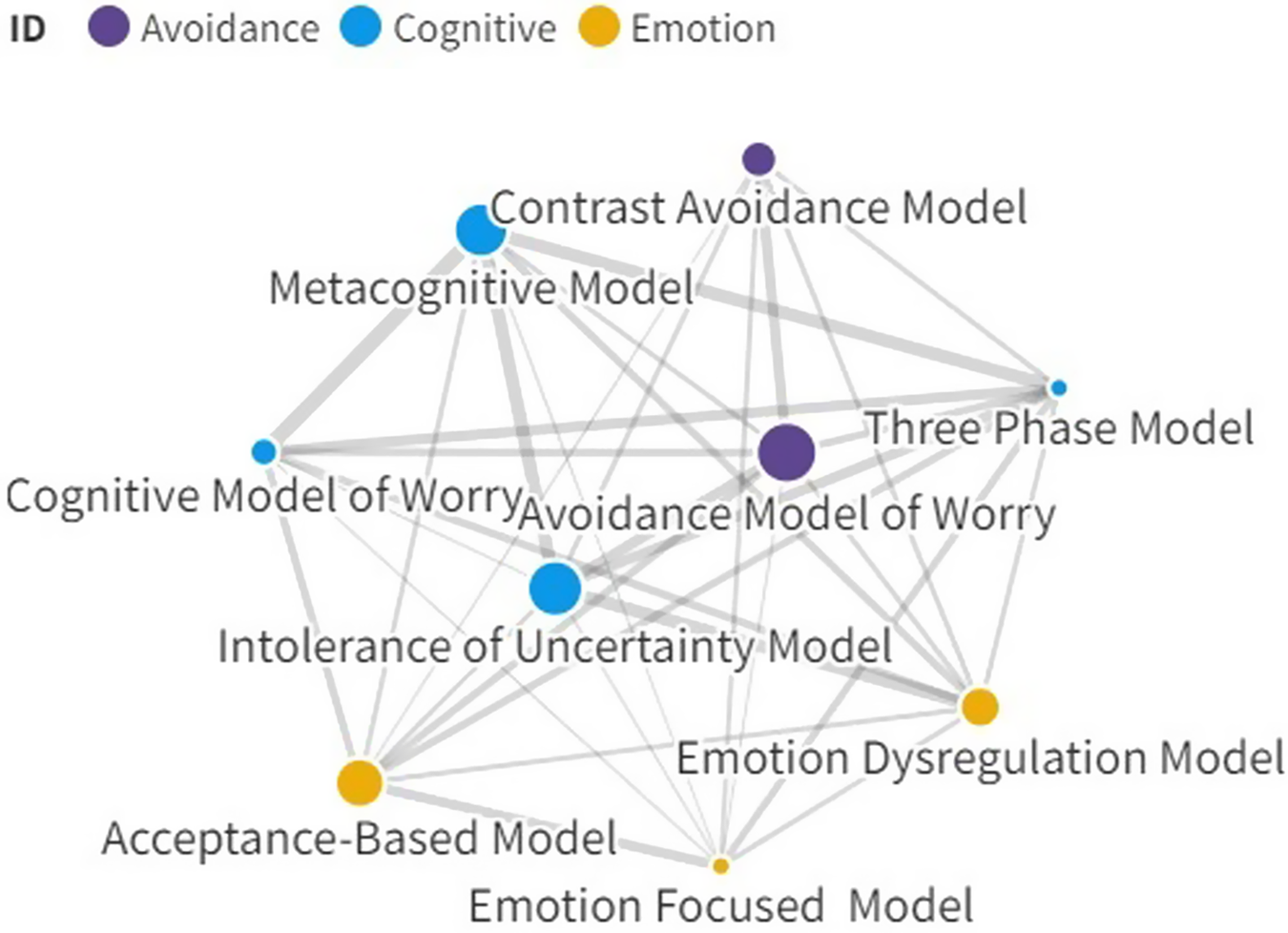

The same data can be used to establish a network between models based on similarity features as can be seen in Fig. 1. The thickness of the edges (joining lines) indicates the degree of similarity between models. The size of the nodes (models) is based on the number of citations of the most cited key source for each model scaled proportional to number of citations, apart from the fact that a minimum size has been set for the least cited models for visual clarity.

Figure 1. Network between models based on similarity features.

Interestingly the original AMW holds a central position, although some of the models are not strongly linked to it. The more recent TPM which has the most features, also shows some degree of similarity with all other models. The overall network suggests that despite unique features in some models (see Table 2) they are all sharing a number of features. Perhaps this is unsurprising given the relative paucity of GAD research over a 35-year period, and especially research on processes, although many of the authors responsible for the models have made major contributions to process research, especially for features central to their models.

In conclusion, the nine models identified overlap to a significant degree. They often cite overlapping literature in empirical support of the models, and they all have treatments that address some or all of the features identified in their models. Later models tend to incorporate features of earlier models, even those that have not developed specifically for GAD, but have been adapted to GAD from more generic models. The models are important because to a large extent, they determine the differing psychological treatments that have been developed for GAD.

Why so many models?

The more distinct features for each model, I would suggest are as follows: Worry as avoidance from the AMW (although incorporated into several others), IU from the IUM, type 2 worry and negative beliefs about worry from the MCM, poor understanding of emotions from the EDM, problematic relationship with internal experience for the ABM, fear/avoidance of emotional contrast from the CAM, core pain (painful feelings) from the EFM, interpretation bias and competing representations from the CMW, and fear/fright from TPM. Thus, although there is a high degree of overlap for other elements, each model has one or more distinct elements that would suggest that different processes could be at play. For example, some of these such as poor understanding of emotions, a problematic relationship with internal experience, fear/avoidance of emotional contrast and even negative beliefs about worry may largely be addressing the same or similar phenomena, albeit from different perspectives and using a different language. Some studies have examined competing constructs simultaneously. For example, among 557 students in Iran, measures of metacognitions, IU, emotional schema, and acceptance collectively accounted for 74% in worry scores; the zero-order correlations between the predictors varied from .21 to .64 (Akbari and Khanipour, Reference Akbari and Khanipour2018). This type of study could be helpful in resolving the question of distinctness empirically, but such a high proportion of variance may indicate criterion confounding and high correlations between predictors suggests that overlap between measures, whether conceptual or semantic, may be an issue (see discussion of measurement issues below).

However, assuming they are distinct, one obvious question is why so many potential processes? At one level the answer probably lies in the name, generalized anxiety disorder. Worry in GAD is not monothematic as is more typically the case in illness anxiety disorder, body dysmorphic disorder, panic disorder, social anxiety disorder and others, although each of these may have different subthemes. OCD often presents in different areas of a person’s life, and ‘hijacks’ areas that are important to them, but it is rarely generalized. But is GAD truly generalized? While worry in GAD is not monothematic, neither is it truly generalized. People with and without GAD do not worry about everything; they worry about things that are important to them. In a series of elegant studies across samples and outwith the clinical domain, Boehnke et al. (Reference Boehnke, Schwartz, Stromberg and Sagiv1998) and Schwartz et al. (Reference Schwartz, Sagiv and Boehnke2000) have linked peoples’ worries to their values. Interestingly, across several cultural groups they have linked worry domains (e.g. health, safety, environment, economics, etc.) to areas of high personal value. Even more interesting is that whether values are expressed at an individual/personal level vs a wider society/world/universal level is associated with micro (personal) vs macro (wider) worries. Most people have more than one thing that is important to them, although what is currently salient may change in response to situations that could be potential threats, whether this happens in the very short term (i.e. hourly) or medium term (i.e. weeks to months), but overall themes may be quite stable over longer periods of time (e.g. Constans et al., Reference Constans, Barbee, Townsend and Leffler2002). The notion that people with GAD worry about minor matters may be understood by studies that show surface topics may connect to concerns in core areas (e.g. Hazlett-Stephens and Craske, Reference Hazlett-Stevens and Craske2003; Provencher et al., Reference Provencher, Freeston, Dugas and Ladouceur2000). The name of the disorder may overstate the case for generalized in the sense of everything, but it is partially accurate in that there is no specific content that defines worry. If we track back 30 years or more, I would suggest that the impact of Beck’s (Reference Beck1976) original cognitive specificity hypothesis was guiding clinical researchers to seek the specific content of different disorders, including GAD (see Breitholtz et al., Reference Breitholtz, Johansson and Öst1999). This paid off extremely well, for example in panic disorder with catastrophic misinterpretations of what was happening in one’s body (e.g. Clark, Reference Clark1986).

This shifting nature of the problem was probably recognized at the origin of GAD as a diagnostic entity, named as ‘free-floating anxiety’. As a much younger researcher in the early 1990s, I was aware that we were trying to establish cognitive specificity for GAD. But the cognitive ‘content’ we found was in fact what I would now consider a process, namely, intolerance of uncertainty, although we framed it cognitively at the time (Freeston et al., Reference Freeston, Rhéaume, Letarte, Dugas and Ladouceur1994). Indeed, at least among people with GAD, cognitive approaches testing beliefs about uncertainty can be very effective in addressing IU and so worry and GAD (e.g. Hebert and Dugas, Reference Hebert and Dugas2019; Dugas et al., Reference Dugas, Sexton, Hebert, Bouchard, Gouin and Shafran2022). Likewise, other clinical researchers at the time, some like us also looking at the content of worry (e.g. Roemer et al., Reference Roemer, Molina and Borkovec1997), probably could not pin down the specific content of worry as it was constantly shifting, and so also focused on processes that could apply to any content. So perhaps it is the absence of specific content that has led to the emergence of multiple processes.

Interestingly, the question of where the content of worry comes from has never gone away, and with varying degrees of explicitness is attributed variously to the proximal and external (e.g. life events in the IUM) and as far as the distal and internal (e.g. the fear phase in the TPM when past events contribute to the fright/fear phase). However, Beck (e.g. Beck et al., Reference Beck, Emery and Greenberg1985) first proposed that anxiety arose as a function of core beliefs about themselves and the world. In a slightly later iteration, D.M. Clark (Reference Clark, Hawton, Salkovskis, Kirk and Clark1989) proposed that ‘The beliefs, or dysfunctional assumptions, which are involved in generalized anxiety are highly varied. However, most revolve around issues of acceptance, competence, responsibility, control, and the symptoms of anxiety themselves’ (p. 56). As has often been the case, Rachman (e.g. Rachman, Reference Rachman1984; Woody and Rachman, Reference Woody and Rachman1994) turned the problem on its head and proposed, from the safety perspective, that the content of worry may not come from the presence of threat, but from the loss of safety, and there are multiple ways to lose safety. In this account, the imbalance of safety and threat may lead everyday personally salient situations to be perceived as potential threats. The recent proposal by Gústavsson et al. (Reference Gústavsson, Salkovskis and Sigurðsson2021) can be seen as drawing on both of these traditions while further emphasizing the distinction between worry as adaptive problem solving directed at realistically solvable problems in contrast to worry as safety seeking behaviour in response to perceived threat (a distinction that is presaged in the IUM in the distinction between reality-based vs hypothetical worry), especially when linked to an inflated sense of responsibility.

Outcome research

Given that disorder-specific CBT models generally lead to treatments, any discussion of models must also be contextualized within the outcome literature. There have been a number of meta-analyses of the treatment of GAD over the last two decades. Meta-analytic studies generally subsume or incorporate the studies included in earlier analyses. Although some more narrowly focused meta-analyses of the treatment of GAD have been published recently, the broadest meta-analysis of GAD dates from 2020, namely, Carl et al. (Reference Carl, Witcraft, Kauffman, Gillespie, Becker, Cuijpers, Van Ameringen, Smits and Powers2020a). This study included 34 trials of broadly CBT treatments for GAD and reported on 40 comparisons versus controls. These were, CBT against pill placebo (k=3, g=1.44, 95% CI: 0.94–1.94, p<0.001), waitlist controls (k=22, g=0.90, 95% CI: 0.73–1.08, p<0.001), psychological placebo (attention control) (k=10, g=0.47, 95% CI: 0.25–0.69, p<0.001), and treatment as usual (TAU, k=5, g=0.38, 95% CI: 0.05–0.71, p<0.05). These effects correspond to a large effect versus pill placebo and waitlist, and small to medium effects versus psychological placebo and treatment as usual. They did not report on active treatment comparisons.

To further contextualize the previous meta-analysis, Chen et al. (Reference Chen, Huang, Hsu, Ouyang and Lin2019) conducted a network meta-analysis on studies between 1981 and 2017 and included 57 pharmacotherapy only studies, 26 psychotherapy only, six self-help only, and two mixed. They concluded that most psychological and self-help interventions showed greater effects than waitlist control, but none had greater effects compared with psychological placebo. Gersh et al. (Reference Gersh, Hallford, Rice, Kazantzis, Gersh, Gersh and McCarty2017) reported specifically on drop-out from individual psychotherapy for GAD; based on 45 studies (N=2224) including some from 2016. They reported a drop-out rate of 16.99% (95% CI: 14.42–19.91%). Cuijpers et al. (Reference Cuijpers, Gentili, Banos, Garcia-Campayo, Botella and Cristea2016) compared outcome for GAD to panic disorder and social anxiety disorder (SAD). Due to the requirement for one or more common/generic outcome measures, the number of studies included for GAD varied from 5 to 22 according to the analysis; the authors reported that outcomes for GAD and SAD were significantly poorer than that for panic. Van Dis et al. (Reference Van Dis, Van Veen, Hagenaars, Batelaan, Bockting, Van Den Heuvel, Cuijpers and Engelhard2020) conducted a meta-analysis of longer-term outcomes of anxiety disorders up until January 2019. For GAD, the effects for 6–12 month follow-up were small-medium (k=11, g=0.40, 95% CI: 0.13–0.67) and small at follow-up of 12 months or more (k=10, g=0.22, 95% CI: 0.02–0.42); notably all prediction intervals included zero. Finally, Springer et al. (Reference Springer, Levy and Tolin2018) included studies up until February 2018 and reported remission for intent-to-treat analyses of 51.4% (95% CI: 35.5–66.9%, k=3) at post-treatment and 65.0% (95% CI: 43.6–81.7%, k=2) at follow-up. For completer analyses, more studies were available and results were similar, namely, 56.3% (95% CI: 50.2–62.2%, k=11) at post-treatment and 65.2% (95% CI: 53.1–75.6%, k=8) at follow-up.

These meta-analyses considered together present a modest picture of treatment outcome for psychological therapies based on a rather small number of studies. Given the relative lack of published research in GAD and despite the previously noted relative preponderance of treatment research in GAD, the evidence base as reported above is small compared with other disorders. However, the Carl et al. (Reference Carl, Witcraft, Kauffman, Gillespie, Becker, Cuijpers, Van Ameringen, Smits and Powers2020a) review was submitted in 2018 and close inspection shows that some studies from 2016 and 2017 had not been included. Using the same search terms as they did (expanded to include British spellings of generalis/zed and also include mindfulness), I conducted a search (13 May 2022) in a single database (Scopus). This rapid scoping review for the current article (single filtering, single rater extraction and single coding) with publication from 2016 to 2022 retrieved 28 non-redundant RCTs (n=3031) that may be eligible according to the Carl et al. (Reference Carl, Witcraft, Kauffman, Gillespie, Becker, Cuijpers, Van Ameringen, Smits and Powers2020a) inclusion criteria (see Data availability section).

What, if any, conclusions can be drawn? First, the overall evidence base for CBT, variants and related therapies potentially available for review will probably include at least the 34 randomized trials included in the Carl et al. (Reference Carl, Witcraft, Kauffman, Gillespie, Becker, Cuijpers, Van Ameringen, Smits and Powers2020a) review and the 28 non-redundant trials identified above, as well as those not retrieved/excluded by them. Second, in the absence of (more) recent meta-analyses that have been willing to look at different versions of CBT and related therapies, we simply do not know how well CBT in general, any of the specific GAD-specific variants, or some of the third wave treatments may be performing for GAD, whether against control conditions (of various types), or against each other; even then many comparisons will be under-powered. Third, many of these studies will be relatively small, especially for comparisons of active treatments. Fourth, if studies are similar to those in the Carl et al. (Reference Carl, Witcraft, Kauffman, Gillespie, Becker, Cuijpers, Van Ameringen, Smits and Powers2020a) meta-analysis, they will be at variable risk of bias, and potentially subject to allegiance effects. Fifth, despite the label on any given treatment protocol, these model-driven treatments for GAD are derived from overlapping models and the content will probably also overlap to a significant degree, including with some of the modular, transdiagnostic or third-wave therapies. Sixth, assuming that such a meta-analysis is conducted by researchers willing to rigorously engage with the intricacies of different variants and consider moderators such as treatment dose (or gradient; see Kazdin, Reference Kazdin2007) and delivery format, it is still unlikely that treatment of GAD, on average, will prove to be as effective as we, the treatment developers and triallists, would like it to be. Further, given that even the most frequently studied protocols still have relatively small numbers of trials and fewer comparisons to attention control or head-to-head comparisons, it is unlikely that any would emerge as a clear winner. Consequently, I would predict that the unsurprising and likely conclusion of such an eventual meta-analysis, despite the concerted efforts over 25 years or more by the developers and triallists, would be a variant of the Dodo bird verdict: Everyone has endeavoured, all have done ‘OK-ish’, and all must have prizes. But all must try harder… and perhaps, I would humbly suggest, try something simpler.

Potential ways forward

Despite the apparent negativity of the previous statement, I remain optimistic; GAD as a clinical problem has engaged and mobilized a number of different creative and dedicated research teams pursuing different constructs often over a considerable period of time. Many who were active in the 1990s are still pursuing treatment gains today. However, these long-established teams, teams developed from them, as well as the relative newcomers have integrated previous or concurrent points of view. While building on what has gone before is a reasonable position, especially given the relatively small volume of process research in GAD, it is perhaps to the detriment of parsimony and specificity in models and treatments.

As a minimum, if we believe we have hit the ceiling of treatment efficacy then there is still the option of getting more out of existing treatments. This is the strategy adopted, for example, by Flückiger et al. (Reference Flückiger, Vîslă, Wolfer, Hilpert, Zinbarg, Lutz, Holtforth and Allemand2021) who varied the focus of treatment and found the emphasizing people’s strengths and abilities (vs more individualizing or their problems) led to better outcome. Likewise Westra et al. (Reference Westra, Constantino and Antony2016) found the addition of motivational interviewing improved some outcomes. It is also important to consider delivery formats to address important issues such as availability, accessibility and cost-effectiveness. For example, a recent study by Carl et al. (Reference Carl, Miller, Henry, Davis, Stott, Smits, Emsley, Gu, Shin, Otto, Craske, Saunders, Goodwin and Espie2020b) tested a fully automated (i.e. ‘gameified’) smartphone CBT intervention. However, if we keep on doing what we are doing with multi-component models, multi-strand treatments, and potentially adding more things in, we will probably get essentially the same outcomes. Outcomes may perhaps increase slowly over time, but what is needed is a step change. So how do we break the pattern?

Process research testing competing processes

Fundamental process research could attempt to simplify models by testing contrasting predictions from two or more of the existing models although these predictions may vary in explicitness. One example would be that threat representations are central to worry and GAD vs intolerance of uncertainty is central to worry and GAD. There have been several attempts to resolve this in different ways (e.g. Anderson et al., Reference Anderson, Dugas, Koerner, Radomsky, Savard and Turcotte2012, Bartoszek et al., Reference Bartoszek, Ranney, Curanovic, Costello and Behar2022; Bredemeier and Berenbaum, Reference Bredemeier and Berenbaum2008; Chen et al., Reference Chen, Yao and Qian2018; Pepperdine et al., Reference Pepperdine, Lomax and Freeston2018), but these have generally been based on the idea that these processes are complementary or interactive rather than the stronger position that these may be competing alternatives.

Single strand treatments

Single strand interventions could be developed, perhaps from existing models, that focus parsimoniously on specific processes, with narrow focus, high dose, and a small number of narrow targeted treatment strategies. As noted previously, most models have one or perhaps two components that are both central to a given model and not shared to a large extent with others, so these may be the target candidates. While this strategy will not establish that the process targeted is causal in the disorder, the right design can establish that targeting a specific process is a mechanism in its amelioration/mitigation (see Kazdin, Reference Kazdin2007). While multiple time points are required in such designs to establish temporal precedence, the key is to establish specificity of change using markers of both the targeted and competing or alternative processes. For example, if it is thought that the core problem of worry is that memories/images of past events intrude into the present and result in worry, then a narrow treatment addressing these memories could be tested, while also measuring competing processes, for example intolerance of uncertainty or meta-worry. Furthermore, Kazdin (Reference Kazdin2007) reminds us that gradient or dose effects are important in identifying mediators, and gradient may be better demonstrated with narrow treatments.

Interestingly, IUM treatments are narrowing although moving in different directions in research groups led by members of the original Laval team. On the one hand, Dugas and colleagues are developing narrower IU treatments for GAD, based on a cognitive/behavioural experiment approach (e.g. Hebert and Dugas, Reference Hebert and Dugas2019; Dugas et al., Reference Dugas, Sexton, Hebert, Bouchard, Gouin and Shafran2022). On the other hand, Freeston and colleagues are developing narrower transdiagnostic treatments for IU (including people with GAD), based on a more experiential/interoceptive approach to the experience of uncertainty (e.g. Mofrad et al., Reference Mofrad, Tiplady, Payne and Freeston2020; Mofrad et al., Reference Mofrad, Payne and Freeston2021). Furthermore, internet-based training approaches are in the translational pipeline that may be good candidates as single-strand interventions, namely negative interpretation bias training (Hirsch et al., Reference Hirsch, Krahé, Whyte, Krzyzanowski, Meeten, Norton and Mathews2021) and meta-cognitive reappraisal training (Ikani et al., Reference Ikani, Radix, Rinck and Becker2022) which by the nature of the tasks maintain narrow focus.

Focus on the individual

Rather than examining GAD from a nomothetic standpoint with what is essentially a latent variable approach, an ideographic approach using time series and network analysis could simultaneously investigate markers for two or more of the competing models along with symptoms of GAD. This could be conducted both observationally before treatment as well as experimentally during treatment. While cross-sectional nomothetic network models have been considered for GAD (e.g. Ren et al., Reference Ren, Yang, Wang, Cui, Jin, Ma, Zhang, Wu, Wang and Yang2020), there are some interesting ideographic examples for other mental health problems (e.g. Hoffart and Johnson, Reference Hoffart and Johnson2020; Piccirillo and Rodebaugh, Reference Piccirillo and Rodebaugh2022). Such an approach may also help challenge or address assumptions of uniformity of processes and the relationships between them across different groups within a society, as well as across different societies and cultures. Intriguingly, this approach could potentially reveal that two or more models and derived treatments ‘have both won, and both deserve prizes’, but not necessarily for the same people, or at the same time.

New processes, or re-focus on already recognized features

Fourth, there is always room for new processes or reconsideration of processes that have not been as central in the models. For example, the role of behaviour in GAD has been considered numerous times over the last 30 years, both specific examples that have been incorporated into models (e.g. problem solving, cognitive avoidance, etc.), and as a more general consideration as the function of worry. Indeed, specific behaviours (avoidance, preparation, procrastination and reassurance seeking) had also been considered as a potential diagnostic feature for DSM-5, but were not implemented (Andrews et al., Reference Andrews, Hobbs, Borkovec, Beesdo, Craske, Heimberg, Rapee, Ruscio and Stanley2010; Brown and Tung, Reference Brown and Tung2018). There have been various studies on different behaviours in GAD over the years (e.g. Beesdo-Baum et al., Reference Beesdo-Baum, Jenjahn, Höfler, Lueken, Becker and Hoyer2012; Clark et al., Reference Clark, Rock, Clark and Murray-Lyon2020; Mahoney et al., Reference Mahoney, Hobbs, Williams, Andrews and Newby2018; Tallis and de Silva, Reference Tallis and de Silva1992) but, perhaps due to the dominating presence of worry, the data do not seem to have led as yet to specific models or interventions with a concerted focus on overt behaviours.

New or refined models

Despite the dozen or so processes already identified in existing models, new or refined models will continue to emerge. For example, Gústavsson et al. (Reference Gústavsson, Salkovskis and Sigurðsson2021) have recently offered a re-analysis of the function of worry. Their re-analysis also re-situates GAD in the familiar framework of over-estimation of threat and the under-estimation of coping as well as worry as a potential safety-seeking behaviour. They also consider the potential role of inflated responsibility and revisit the idea of mood as input as possible contributing factors. Importantly they lay out a plan for empirical investigation of some differential predictions. Whether this re-analysis leads to a new direction in model development and a re-focus or slimming down of treatment (versus adding more in) remains to be seen.

Consider abandoning diagnostic categories like GAD in favour of dimensions

Perhaps the problem is not GAD as a specific category, but current diagnostic systems. Some people have argued that construing mental health in a categorical way in general is getting in the way of progress (see Conway et al., Reference Conway and Krueger2021). The National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) developed the Research Domain Criteria (RDoC; see Cuthbert and Insel, Reference Cuthbert and Insel2013) as an alternative to the diagnostic approach to clinical research and psychopathology by proposing dimensional constructs. More recently, a consortium of researchers developed the Hierarchical Taxonomy of Psychopathology (HiTOP; Kotov et al., Reference Kotov, Krueger, Watson, Achenbach, Althoff, Bagby, Brown, Carpenter, Caspi, Clark, Eaton, Forbes, Forbush, Goldberg, Hasin, Hyman, Ivanova, Lynam, Markon and Zimmerman2017) which also espouses a dimensional approach. Both move away from a purely categorical system of psychiatric nosology, and a degree of correspondence can be established between the two systems (see Michelini et al., Reference Michelini, Palumbo, DeYoung, Latzman and Kotov2021). Early psychometric work on the negative valence systems within the RDoC framework has identified a factor called potential threat (Hasratian et al., Reference Hasratian, Meuret, Chmielewski and Ritz2022). This factor has elements of worry and behavioural inhibition and is distinct to factors of acute threat, sustained threat, loss, reactive aggression, and positive valence. Similar work is underway within the HiTOP framework, but currently appears to be at the level of broad internalizing or distress (Watson et al., Reference Watson, Forbes, Levin-Aspenson, Ruggero, Kotelnikova, Khoo and Kotov2022). It remains to be seen whether treatments targeting dimensions rather than nosological categories will have the same issues as many of those targeting categories, namely, multiple treatment packages with multiple interventions, with differing emphasis. Simply defining something as dimensional rather than categorical does not automatically address problems of specificity and parsimony, especially if people believe that there is more than one specific factor underlying a given dimension.

Measurement is key

The different approaches to seeking better models and so treatments for worry and GAD (in current nosologies) are in many cases complementary, but all of them will require markers of key processes. These markers need to be easy to use, brief, narrow in definition, avoid semantic overlap with each other, and avoid confounding with distress and worry. Some processes may have markers that are easier to establish, for example by short versions of existing questionnaires, but others may require behavioural or physiological markers, or at least proxies of them. Interestingly, Perrin and colleagues have used a battery of shortened five-item scales to operationalize the components of the IUM model for a series of studies among children and adolescents, including a pilot RCT (Perrin et al., Reference Perrin, Bevan, Payne and Bolton2019), but this has not been common practice for studies of adults. An example of a brief process measure in the anxiety disorders is the Short Scale Anxiety Sensitivity Index (SSASI; Zvolensky et al., Reference Zvolensky, Garey, Fergus, Gallagher, Viana, Shepherd, Mayorga, Kelley, Griggs and Schmidt2018) with five items instead of the original 18. For worry and GAD, there is already an established three-item version of worry (Kertz et al., Reference Kertz, Lee and Björgvinsson2014) as well as a recently proposed five-item version of the Intolerance of Uncertainty Scale (Bottesi et al., Reference Bottesi, Mawn, Nogueira-Arjona, Romero Sanchiz, Simou, Simos, Tiplady and Freeston2020). Crouch et al. (Reference Crouch, Lewis, Erickson and Newman2017) have reported on a four-item situational negative contrast measure, a reduced version of the Contrast-Avoidance Questionnaire (Llera and Newman, Reference Llera and Newman2017). Developing such markers represents a methodological/psychometric challenge, but it also represents a conceptual challenge to theoreticians and proponents of models to narrowly define key processes and make narrow claims for the specific or even unique features of their models. For example, the seven-item Acceptance and Action Questionnaire-II (Bond et al., Reference Bond, Hayes, Baer, Carpenter, Guenole, Orcutt, Waltz and Zettle2011) has been proposed as a marker of experiential avoidance, but some have questioned its discriminant validity (e.g. Tyndall et al., Reference Tyndall, Waldeck, Pancani, Whelan, Roche and Dawson2019). Furthermore, multi-dimensional measures such as the Meta-Cognitive Questionnaire-30 (MCQ-30; Wells and Cartwright-Hatton, Reference Wells and Cartwright-Hatton2004) and the Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale (Gratz and Roemer, Reference Gratz and Roemer2004) may require identifying the beliefs or process believed to be most central to each model as well as shortening of subscales, and in some cases, reducing confounding. Using network analysis on the MCQ-30, Nordahl et al. (Reference Nordahl, Anyan, Hjemdal and Wells2022) found that beliefs about the need for control are central to the network. Consequently, a short unconfounded subscale based on these beliefs about control could be a potential candidate for a short, focused measure representing a key feature of the MCM. Development of a battery of such measures would not only facilitate research as Perrin et al. (Reference Perrin, Bevan, Payne and Bolton2019) have done for the IUM, but would also help clinicians in routine assess, formulate, and then track change not only on symptoms, but also on processes that may mediate symptomatic change.

‘One size fits all’ versus ‘One size fits me’

If one or more of these strategies is successful, then perhaps we will not have more ‘one size fits all treatments’ for GAD, but a few narrow modules and so ‘my size fits me’, treatments (see Schaeuffele et al., Reference Schaeuffele, Schulz, Knaevelsrud, Renneberg and Boettcher2021). The idea of modular treatment for anxiety disorders is not new, nor is the idea of transdiagnostic treatment, and these may overlap in some cases (e.g. Schaeuffele et al., Reference Schaeuffele, Schulz, Knaevelsrud, Renneberg and Boettcher2021). However, the current modular treatments (e.g. The Unified Protocol; see Carlucci et al., Reference Carlucci, Saggino and Balsamo2021; Reinholt et al., Reference Reinholt, Hvenegaard, Christensen, Eskildsen, Hjorthøj, Poulsen, Arendt, Rosenberg, Gryesten, Aharoni, Alrø, Christensen and Arnfred2022), transdiagnostic treatments (e.g. Gonzalez-Robles et al., Reference Gonzalez-Robles, Diaz-Garcia, Miguel, Garcia-Palacios and Botella2018), and third wave treatments (e.g. Dahlin et al., Reference Dahlin, Andersson, Magnusson, Johansson, Sjögren, Håkansson, Pettersson, Kadowaki, Cuijpers and Carlbring2016; Wong et al., Reference Wong, Yip, Mak, Mercer, Cheung, Ling and Ma2016) are probably achieving no better outcomes than the treatments based on the GAD-specific models discussed in this paper, although some may have possible advantages in terms of dissemination and treatment delivery. Essentially, these treatments often share some of the same issues as the disorder-specific treatments, notably multiple targets, multiple semi-matched interventions, and so a lack of specificity, and so potentially a lower dose of the ‘active ingredient’. However, if we knew what the active ingredients were and could deliver them narrowly, then the interesting question as to whether there is synergy or interaction between interventions could be examined, perhaps through single-case approaches where there is a tradition of dismantling designs and manipulation of the order of distinct interventions.

Implications for practice

Of the potential ways forward, many are longer term endeavours, but three are perhaps closer to implementation now or in the near future. First, single strand treatments may be possible. As noted above, there are two narrow variants or single strand treatments for the IUM. Another possible candidate is a 10-day single-strand momentary monitoring intervention where Lafreniere and Newman (Reference LaFreniere and Newman2016) developed a rationale for a specific worry outcome journal that showed significant post-treatment improvement in GAD symptoms versus a thought journal, although higher treatment dose may be required. Second, some brief measures already exist, so some processes from some models may be ready to track with short measures allowing several processes to be tracked simultaneously. Finally, ‘one size fits me’ may be available to a limited degree, for example, in choosing before two IU interventions. For example, if the person presents with a clear cognitive representation of disliking uncertainty, then a behavioural experiment approach may suit to test out specific uncertainty beliefs (Hebert and Dugas, Reference Hebert and Dugas2019; Dugas et al., Reference Dugas, Sexton, Hebert, Bouchard, Gouin and Shafran2022). However, if this is not present and the person’s theory B is simply ‘I wouldn’t like it’, then working on the felt sense of uncertainty may suit better (Mofrad et al., Reference Mofrad, Payne and Freeston2021). If other single strand options emerge, or evidence of differential indications for other approaches is found, then the range and indication of ‘one size fits me’ options should increase.

Limitations

This review has set out to establish trends and patterns in the psychological understanding and treatment of GAD. It has not examined the support for each model, nor the evidence for specific treatments derived from each model. The analysis of the models at the component level has been conducted by a single rater. The components identified may not represent those that the proponents of the models would argue are most central, but they can be found in the description of the models by the original authors. This article proposes that the overlap between the models of GAD and the number of components in the models are factors that may limit progress, but there will be other potentially limiting factors. Some suggestions of how models and their derived treatments could become more narrowly specified have been identified. None of these suggestions is original, but each may have something to offer in the case of GAD; neither is the list exhaustive. Some of the arguments made here may not be specific to GAD, and may also apply to other mental health problems, for example to obsessive-compulsive disorder.

In many ways the situation with CBT models and treatments for GAD is similar to that in depression as described by Dunn et al. (Reference Dunn, O’Mahen, Wright and Brown2019) with multiple treatments, stalled outcomes, and a problem (GAD) that may not be as heterogenous in presentation as depression, but is heterogenous in content. If the situation and issues are similar, so may be some of the remedies. Dunn and colleagues not only remind us about how successful anxiety treatments have been developed (citing Salkovskis, Reference Salkovskis2002, and Clark, Reference Clark2004), but also identify sources of research waste and how to reduce them. For example, there are at least four teams in the UK pursuing different models of GAD, but contingencies favour the separate pursuit of knowledge for each model. Finally, they highlight the role of experts by experience in treatment development and co-design, which in this case includes, but is not limited to, people with GAD, people who have and have not benefited from treatment, as well as clinicians in various setting who deliver (or not) the various treatments that been developed (see also INVOLVE, 2021).

Finally, the models included here have all been developed predominantly by researchers in Canada, the US, the UK and Ireland. To varying degrees, they all appear to share a series of common assumptions about GAD, psychological models, and how we make sense of peoples’ experiences. They over-represent one or very few of many possible ways of understanding worry in particular and distress about possible futures more generally. I have used a very similar lens in this review and so I am ‘marking my own homework’. For example, an even broader version of the work across cultural groups such as that conducted over two decades ago by Boehnke, Schwartz and colleagues linking values to worry could be very helpful. From my standpoint, other voices are needed, should be encouraged, and will be welcomed.

Conclusion

Given the high lifetime co-morbidity of GAD and features of GAD that are broadly shared [e.g. worry (Dugas et al., Reference Dugas, Freeston, Ladouceur, Rhéaume, Provencher and Boisvert1998a), as well as associated features such as sleep, irritability, fatigue, etc.], successful narrow treatments for GAD targeting a specific process, will in all likelihood result in interventions that are transdiagnostic in two ways; first, they target common processes, and second, they should be effective for different disorders. Therefore, dissemination and training for a small number of single strand treatments may not be a significant issue compared with developing more or different multi-strand packages for the same or different problems (McManus et al., Reference McManus, Shafran and Cooper2010). If more effective treatments exist, then the advances we have seen in the technology of dissemination, training, delivery and accessibility can be applied to better ‘active ingredients’. The hope, as always, is that when matched to the right person, ‘my size fits me’ treatments focused on specific targets may achieve better outcomes than the current broader treatments. If so, better outcomes achieved in different ways with different narrow modules at the level of the individual could lead to a step change in outcome at the group level.

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are openly available at: http://doi.org/10.25405/data.ncl.21578751

Acknowledgements

While these views are my own, they have been shaped by many conversations with collaborators, colleagues and students over thirty years. I am very grateful to the commitment of these clinicians, academics and students for their contributions to the studies, the ideas and to their enthusiasm for developing a better understanding and treatment of worry.

Author contributions

Mark Freeston: Conceptualization (lead), Data curation (lead), Formal analysis (lead), Investigation (lead), Methodology (lead), Validation (lead), Visualization (lead), Writing – original draft (lead), Writing – review & editing (lead).

Financial support

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflicts of interest

I receive royalties for books and honoraria for training on generalized anxiety disorder, worry and similar topics.

Ethical standards

The author has followed the Ethical Principles of Psychologists and Code of Conduct as set out by the BABCP and BPS in the writing of this article. No participant data are reported in this article.

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.