Introduction

The application of behavioral science to public policy challenges in the form of Behavioral Public Policy (BPP) has been increasingly integrated into governmental functions as ‘nudge units’ and regularly deployed to encourage the public's adherence to desirable civic behaviors (Hallsworth et al., Reference Hallsworth, List, Metcalfe and Vlaev2017; Fishbane et al., Reference Fishbane, Ouss and Shah2020; Holz et al., Reference Holz, List, Zentner, Cardoza and Zentner2020) and address widespread societal challenges (Almeida et al., Reference Almeida, Lourenço, Dessart and Ciriolo2016; Chapman et al., Reference Chapman, Li, Leventhal and Leventhal2016; OECD, 2017; Garnelo et al., Reference Garnelo, Bustin, Duryea and Morrison2019). Solutions often take the form of improved ‘choice architecture,’ created by identifying key moments of decision-making or behavior and altering the environment in which options are presented with the intent of encouraging more desirable choices when people's preferences are known but their follow-through is lagging.

While this approach has garnered considerable success (OECD, 2017), scaling individual solutions remains a challenge in part because the heterogeneous nature of interventions and the tendency to optimize for individual contexts can make solutions difficult to transplant elsewhere (Bates & Glennerster, Reference Bates and Glennerster2017; Kuehnhanss, Reference Kuehnhanss2019; Bryan et al., Reference Bryan, Tipton and Yeager2021). In addition, although there are examples of applying behavioral science more expansively to organizational units (Camerer & Malmendier, Reference Camerer, Malmendier, Diamond and Vartiainen2007; Hauser et al., Reference Hauser, Linos and Rogers2017) or communities (Feng et al., Reference Feng, Oyunsuren, Tymko, Kim and Soman2018b), and in codified approaches such as Darton and Horne's (Reference Darton and Horne2013) ISM Tool that recognize the influence of infrastructural factors on behavior, BPP's dominant problem-solving frame typically remains narrowly focused on immediate choice environments. As a result, the field's appetite and ability to grapple with externalities or systems-level inequities and imbalances remain limited.

Promisingly, several recent perspectives to address these gaps and tendencies have begun to emerge, among them ‘advanced’ BPP that contributes a more holistic, bottom-up lens to behavioral policy development practices (Ewert, Reference Ewert2019; Ewert & Loer, Reference Ewert and Loer2021), the increasing recognition of cultural, structural, and identity-driven aspects of decision-making (MacKay & Quigley, Reference MacKay and Quigley2018; van Bavel & Dessart, Reference van Bavel and Dessart2018), and the integration of behavioral science with complex, adaptive systems thinking (Lambe et al., Reference Lambe, Ran, Jürisoo, Holmlid, Muhoza, Johnson and Osborne2020; Schmidt & Stenger, Reference Schmidt and Stenger2021b; Bickley & Torgler, Reference Bickley and Torgler2021). These positions have been bolstered by public health perspectives that recognize solutions within complex systems must look beyond tweaks to immediate choice architecture environments, and instead address the ways in which broader system conditions contribute to individuals’ abilities to choose and maintain preferred behaviors (Rutter et al., Reference Rutter, Savona, Glonti, Bibby, Cummins and Finegood2017; Bradley et al., Reference Bradley, Mansouri, Kee and Garcia2020; Greenhalgh, Reference Greenhalgh2020). Achieving a greater scale of impact may therefore require expanding BPP's unit of analysis from discrete interventions for individual behavioral change to system conditions, and from choice architecture's focus on immediate decision environments to turning a behavioral science lens on the underlying processes and structures – the ‘choice infrastructure’ – that support choice architecture solutions and ensure they function effectively.

This article will first describe how developing choice infrastructure can augment the familiar notion of choice architecture in BPP, supporting the effective design of choice-making environments by expanding its remit to improve the ‘plumbing’ within institutional systems (Duflo, Reference Duflo2017). Next, it will describe how greater attention to choice infrastructure can improve current BPP practices by considering how conditions affect the behaviors of multiple system stakeholders, rather than just individual end-users, and how using behaviorally informed principles to shape these conditions can help inform specific interventions and contribute to maintaining system integrity. It then proposes using a ‘SPACE’ model to help practitioners systematically analyze current systems and develop new choice infrastructure using the case example of Chicago food licensure, and concludes with implications and considerations related to embracing this new set of practices.

From choice architecture to choice infrastructure

There are increasing indications that a broader systems perspective may prove beneficial to BPP when navigating complex challenges. Evaluations of standalone interventions to address behavioral challenges currently prioritize short-term behavior change indicators over longer-term outcomes (Sanders et al., Reference Sanders, Snijders and Hallsworth2018; Ewert, Reference Ewert2019), which can lead to brittle results or limited impact in public policy settings due to emergent conditions or adaptation (Schmidt & Stenger, Reference Schmidt and Stenger2021a) or in the face of more ambiguous ‘wicked’ challenges characteristic of complex system environments (Rittel & Webber, Reference Rittel and Webber1973; Buchanan, Reference Buchanan2020). In addition, even successfully solving last-mile challenges can contribute to downstream challenges if the adoption of desirable behaviors contributes to system imbalances or issues of capacity (Andersson et al., Reference Andersson, Campos-Mercade, Meier and Wengstrom2020).

Traditional emphases on specific end-user behavioral change can also confer a degree of selection bias to intervention engagement, focusing on methods that target participant involvement or adoption while neglecting how adjacent issues of access deter individuals from participating at all, or how institutional norms, structures, and processes compose environmental conditions that impact how interventions are interpreted and acted upon. For example, early approaches to boost COVID-19 vaccine uptake that focused on message framing to overcome vaccine hesitancy overlooked the fact that concerns about taking time off to receive the vaccine and manage potential side effects were greater deterrents for certain populations (Artiga & Hamel, Reference Artiga and Hamel2021). In such cases, even well-designed nudges may struggle to overcome infrastructural challenges that limit access, either real or perceived.

Furthermore, BPP's focus on correcting for human cognitive heuristics and biases implicitly suggests that inadequate judgment and decision-making are most efficiently addressed by addressing people's individual deficits through improved choice architecture, while potentially ignoring the importance of deficiencies in the micro-systems in which people function. While to some degree this hesitation to tackle broader choice environments reflects BPP's intentional choice to prioritize low-cost and low resource-intensive interventions (Sanders et al., Reference Sanders, Snijders and Hallsworth2018), it also elides a more thorough exploration of alternate reasons for ‘irrational’ decision-making, such as how the limitations of underlying structures and supports might make certain options infeasible or even incomprehensible to targeted populations.

Research on the unbanked, for example, indicates several ways in which individuals’ resistance to engaging in ostensibly rational banking behaviors may be less due to failures of persuasion than because seemingly secondary conditions encountered by potential customers – lengthy and obtuse forms threatening penalties for incorrect information, or navigating unfamiliar social norms within financial institutions – are seen as impediments (Bertrand et al., Reference Bertrand, Mullainathan and Shafir2006). Barriers to access can also occur within larger underlying system operations and functions themselves, as when financial constructs that have become normalized as foundational (such as direct deposit or credit scores) are inaccessible to populations paid by check or cash. In these cases, lack of access to processes and structures deemed essential for financial engagement may dissuade ‘have-nots’ from even attempting to participate in these services, suggesting that seemingly irrational non-participation or reactant behavior should sometimes be seen as indicative of infrastructural failures, rather than personal ones.

Finally, neglecting to sufficiently examine how underlying infrastructures create system conditions that impact behavior risks overlooking the fact that systems into which solutions are placed may be inherently inequitable, and that system stability does not necessarily equate to system health (Schmidt & Stenger, Reference Schmidt and Stenger2021b). It can also inadvertently presume the presence of universal values, access, and opportunity where they do not exist, and result in solutions that benefit certain communities, solutions, and outcomes over others even while ostensibly promising free choice to all (Winner, Reference Winner1980; Anderson, Reference Anderson1993). For example, despite the imperative to provide no-cost COVID vaccinations to all – including those without insurance – US pharmacies’ request for insurance information in an effort to recoup their own administrative costs prior to administering the shot remains a genuine deterrent (Chen & Jameel, Reference Chen and Jameel2021). For all these reasons, while improving choice architecture to address individual behavioral change can and should remain core to BPP's toolkit, improving underlying choice infrastructure to increase system equity and effectiveness is surely worthy of BPP's heightened attention.

Defining ‘choice infrastructure’ in BPP

Traditional forms of infrastructure – operational platforms, services, and processes such as internet connectivity, or telecommunications and financial networks – already provide support for a wide range of behavioral interventions to help them function predictably and at scale in solutions that employ text messaging prompts (Castleman & Page, Reference Castleman and Page2015; Dai et al., Reference Dai, Saccardo and Han2021), auto-deduction and auto-escalation features (Chapman et al., Reference Chapman, Li, Leventhal and Leventhal2016), or the ability to capture personal data to maintain desired behaviors (Mitchell et al., Reference Mitchell, White, Lau, Leahey, Adams and Faulkner2018). However, broader conceptions of infrastructure also increasingly include a range of underlying socio-material structures and activities, such as social media and open-source platforms, which are generative and relational rather than purely functional or technical in nature (Star & Bowker, Reference Star, Bowker, Lievrouw and Livingstone2002; Ehn, Reference Ehn2008). The dawning realization that infrastructure is not merely a passive or agnostic underlying set of functions but is itself imbued with values and biases – as exemplified by solutions for the unbanked described above or the limited efficacy of implicit bias training in the face of embedded system bias (Onyeador et al., Reference Onyeador, Hudson and Lewis2021) – only increases the necessity and urgency of treating it as a distinct subject of inquiry (Star & Bowker, Reference Star, Bowker, Lievrouw and Livingstone2002).

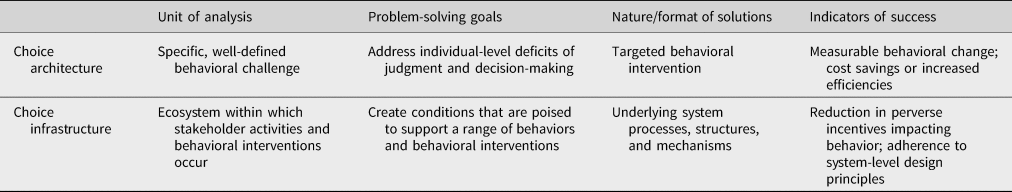

Despite this, promoting infrastructure itself as a primary candidate for reconfiguration to support desired behaviors, rather than as one relegated to promulgating behavioral interventions, is currently underexplored and underemployed in BPP (Senge, Reference Senge1990; Spotswood & Marsh, Reference Spotswood, Marsh and Spotswood2016). As a result, practitioners currently have few tools for applying systems thinking to behavioral interventions, or for systematically diagnosing when insufficient infrastructure might be keeping individuals from adopting behaviors in their best interests. This suggests that introducing a mindset and methodology oriented toward developing effective choice infrastructure in BPP to augment the use of choice architecture may be a useful complement (Table 1).

Table 1. Key attributes of choice architecture and choice infrastructure

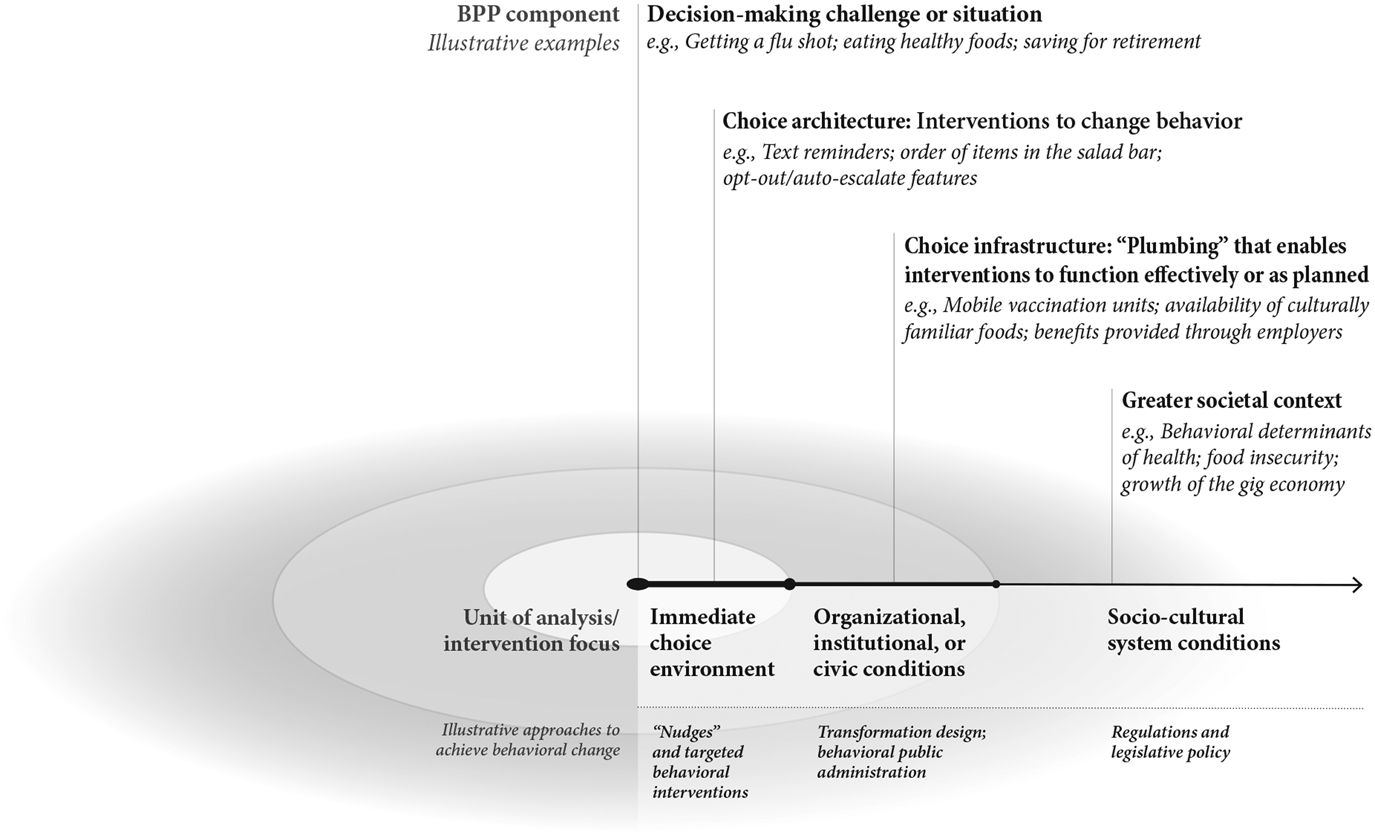

If extending behavioral attention beyond choice architecture provides a starting point for choice infrastructure, defining its outer boundary is equally essential. While increased attention to choice infrastructure intentionally broadens the territory of behavioral insight to include second-order system conditions into which first-order interventions are placed (Watzlawick et al., Reference Watzlawick, Weakland and Fisch1974; Levy, Reference Levy1986; Sangiorgi, Reference Sangiorgi2011), it should not be confused with attempting to solve the full and complex set of socio-political conditions such as food deserts or cultural challenges such as behavioral determinants of health. Rather, choice infrastructure efforts may be best aimed at addressing conditions that more directly limit the feasibility, accessibility, or perceived relevance of solutions without resorting to regulatory might. As such, designing choice infrastructure should be regarded neither as simply another form of targeted intervention or mega-nudge, nor as a solve-all for massive societal challenges, but instead as an activity that is concerned with reshaping the institutional conditions and mechanics of systems – the structures, processes, and capabilities – that directly underlay and support behavioral interventions to help choice architecture solutions work effectively and as planned (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Distinguishing Between Choice Architecture, Choice Infrastructure, and Societal Forces Through Comparative Illustrative Examples and Units of Analysis.

Applying a behavioral perspective to organization, publics, and civil servants has increasingly been reflected in the field of behavioral public administration (Grimmelikhuijsen et al., Reference Grimmelikhuijsen, Jilke, Olsen and Tummers2017) and in perspectives that position public management as a design activity (Barzelay, Reference Barzelay2019). However, further developing methodological approaches to choice infrastructure that complement current strengths of BPP may benefit from three shifts: expanding the unit of analysis from individual interventions to ‘second-order’ conditions of systems (Watzlawick et al., Reference Watzlawick, Weakland and Fisch1974; Levy, Reference Levy1986; Sangiorgi, Reference Sangiorgi2011); targeting multi-stakeholder behavioral dynamics (Meroni, Reference Meroni2008); and considering how systems-level behavioral principles can guide the design of improved infrastructural conditions.

System conditions

Just as humans do not always act in their own best interests, systems do not always support the behaviors they purport to value: health care systems deprioritize preventive activities that forestall downstream health issues (Benjamin, Reference Benjamin2011), companies striving to be innovative often reward risk aversion instead (Kahneman & Lovallo, Reference Kahneman and Lovallo1993), and academic institutions that value increased diversity pursue rankings that reward the status quo (Hatch & Curry, Reference Hatch and Curry2020). Given that individuals’ behaviors and sense of options are often shaped and reinforced by the systems in which they function, designing for behavior within complex systems is therefore likely to benefit from a closer examination of underlying systemic structures and leverage points (Meadows, Reference Meadows1999; Lang & Rayner, Reference Lang and Rayner2012; Rutter et al., Reference Rutter, Savona, Glonti, Bibby, Cummins and Finegood2017).

Efforts to reshape interactions through the deliberate design of internal structures and capabilities in public services already exist in the discipline of transformative service design, or ‘transformation design’ (Burns et al., Reference Burns, Cottam, Vanstone and Winhall2006; Parker & Parker, Reference Parker and Parker2007; Bijl-Brouwer, Reference Bijl-Brouwer2017). This set of practices intentionally shifts traditional emphases on service design – that is, services as primary outputs – to ‘design for services,’ which prioritizes the development of foundational, system-level functions and environments that allow those services to be effectively and efficiently delivered (Kimbell, Reference Kimbell, Gulier and Moor2009; Sangiorgi, Reference Sangiorgi2011). BPP may similarly benefit from this mindset shift, moving from an emphasis on discrete behavioral interventions to ‘design for behavioral public policy,’ which strives to cultivate fertile ground for interventions through increased attention on the design of institutional conditions that allow solutions to flourish.

This may be particularly important in complex environments, in which interventions both impact and are acted upon by other system components and forces (Dorst, Reference Dorst2019; Schmidt & Stenger, Reference Schmidt and Stenger2021a). For example, a texting intervention to encourage parents to adopt new child development activities in small Nicaraguan communities failed to get traction when community dynamics, such as informal conversations between study participants or resentment from local leaders who felt the distribution of cell phones did not sufficiently recognize their rank, interfered with intended behavioral change (Barrera et al., Reference Barrera, Macours, Premand and Vakis2020). Similarly, the use of digital websites for COVID-19 vaccination appointment signup that assumed internet access and the bandwidth to refresh signup sites as appointments became available disregarded that these conditions were not reliable or universal for all.

Where improving choice architecture tends to emphasize individual instances of behavioral change, focusing on institutional-level infrastructural conditions also allows practitioners to better design for constellations of interconnected activities (Trenchard-Mabere, Reference Trenchard-Mabere and Spotswood2016). For example, traditional behavioral approaches to hiring often employ tactics such as ‘blinding’ applications, which remove telltale racial, age, and gender-identifying prompts to attract historically marginalized or excluded peoples (Gaucher et al., Reference Gaucher, Friesen and Key2011; Åslund & Skans, Reference Åslund and Skans2012 ; Bohnet, Reference Bohnet2016). Even when these individual interventions are successful, however, inequities perpetuated by broader institutional conditions – lack of mentorship once individuals are hired, or imbalances in service loads, exposure to professional opportunities, and funding—may prevent organizations from achieving their intended goals (Onyeador et al., Reference Onyeador, Hudson and Lewis2021). More deliberate attention to system conditions can help policymakers address these non-linear or emergent aspects of behavioral challenges more proactively, and in keeping with institutional values (Rickles et al., Reference Rickles, Hawe and Shiell2007).

Finally, where choice architecture focuses primarily on course-correcting wayward human cognition and behavior, making conditions the subject of inquiry recognizes that human decision-making is frequently shaped by systems that may be optimized for operational efficiency, system beneficiaries, and legacy functions rather than for end-user participants (Lang & Rayner, Reference Lang and Rayner2012). For example, while women-led mentoring programs can help fellow women move up within organizations, they often do so by promoting tips about how to ‘play the game’ or navigate system conditions that have historically rewarded men (Behie & Dennis, Reference Behie and Dennis2021). As a result, even success stories perpetuate processes, structures, and policies that continue to reward the usual suspects, norms, and paths to achievement (Heilman, Reference Heilman2001; Murrell & Blake-Beard, Reference Murrell and Blake-Beard2017). Renewed attention to underlying conditions within organizations and institutions instead can help practitioners better identify how investment, processes, and structures may need to extend beyond individuals by illuminating how systems themselves are constructed to reward some populations or values over others (Trenchard-Mabere, Reference Trenchard-Mabere and Spotswood2016).

Multistakeholder environments and ‘choice posture’

Taking an ecological view also requires accommodating a multiplicity of system stakeholders (Meroni, Reference Meroni2008), designing for interactions as well as individual behaviors, and recognizing where unintended consequences may occur when different actor-agents’ incentives for action are misaligned or in conflict. In the context of civic services, for example, choice infrastructure ‘plumbing’ shapes both end-user environments and those of front-line agents responsible for delivering those services, in the form of performance metrics, incentives, and norms (Duflo, Reference Duflo2017; Moseley & Thomann, Reference Moseley and Thomann2021). As a result, interventions intended to improve patient or citizen experiences within healthcare or civic systems, for example, may cause unexpected tensions and reduced system function if the new behaviors asked of healthcare providers and civil servants – taking time to establish personal rapport or follow-up to resolve issues – are not aligned with personal goals or incentives, such as compensation based on calls per hour or fee-for-service structures (Doran et al., Reference Doran, Maurer and Ryan2017).

In addition, although BPP interventions increasingly recognize the importance and value of cultural differences when designing and implementing interventions (Henrich et al., Reference Henrich, Heine and Norenzayan2010; Banerjee et al., Reference Banerjee, Promothesh, Mishra and Mishra2019), the presumption of generalized or average attributes across intervention audiences may still fail to address the diversity of individual goals, incoming expectations and mental models, and choice contexts of assorted actor-agents in system contexts (Gomes & Gubareva, Reference Gomes and Gubareva2021). These various choice ‘postures’ or stances are frequently highly intertwined with other actors (Trenchard-Mabere, Reference Trenchard-Mabere and Spotswood2016) informed by personal lived experience (Spotswood & Marsh, Reference Spotswood, Marsh and Spotswood2016; Ewert & Loer, Reference Ewert and Loer2021), and continually evolving and adapting over time (Bickley & Torgler, Reference Bickley and Torgler2021). This suggests that methods to help practitioners recognize diverse choice postures, in addition to diverse contexts and populations, can illuminate embedded assumptions about how situations, interventions, or options may be interpreted, as well as how seemingly ‘irrational’ choices may be influenced by a broader set of experiences and environmental conditions (Bertrand et al., Reference Bertrand, Mullainathan and Shafir2006; Baumard & Sperber, Reference Baumard and Sperber2010; Ceci et al., Reference Ceci, Kahan and Braman2010).

Principles-driven design

The same application of experimental findings to real-world contexts that works well for targeted interventions may be less effective when applied to system challenges, which require solutions to flex according to variable contexts or as new conditions emerge (Howlett, Reference Howlett2020; IJzerman et al., Reference IJzerman, Lewis, Przybylski, Weinstein, DeBruine, Ritchie, Vazire, Forscher, Morey, Ivory and Anvari2020; Schmidt & Stenger, Reference Schmidt and Stenger2021b). In the same way that traditional infrastructure must accommodate different services and usage variability, choice infrastructure must similarly be up to the task of stewarding a wide range of discrete solutions without prescribing the specifics of any individual one (Hallsworth, Reference Hallsworth2011). This suggests that where choice architecture solutions benefit from precision, infrastructural approaches that focus on correcting underlying system inefficiencies and conditions may benefit from establishing design principles that encourage solution flexibility while maintaining system consistency and integrity (Meadows, Reference Meadows1999).

As such, a successful principles-driven approach to choice infrastructure should be equipped to delineate guidelines for desirable conditions that support specific on-the-ground interventions without explicitly dictating solutions. By providing standards that can be used generatively to shape the characteristics of individual interventions, well-defined principles or ‘decision rules’ can therefore flexibly inform a wide range of solutions that still adhere to larger system goals (Hauser et al., Reference Hauser, Gino and Norton2018; Schmidt, Reference Schmidt, Boess, Cheung and Cain2020). A public policy example of this sensibility already exists in suggestions that policy might be best conceived of as a set of concrete but high-level attributes and intents, which directionally guide – but do not prescribe – specific instantiations that can be customized to suit the particulars of various contexts (Hallsworth, Reference Hallsworth2011). Similarly, behaviorally informed, bottom-up, self-organization has been positioned as a way to address complexity in the face of a plurality of perspectives (Colander & Kupers, Reference Colander and Kupers2014; Ewert & Loer, Reference Ewert and Loer2021), reinforcing the notion that BPP in a system context might be usefully conceived as a set of principles rather than strictly or universally applied edicts.

Finally, design principles can contribute an additional boost to behavioral problem-solving when embedded within system infrastructures by providing mechanisms to reinforce community or organizational cultural values. Two well-known examples in the commercial space – ALCOA, where Paul O'Neil's mantra of workplace safety permeated processes and shaped behaviors across the company (Schwartz, Reference Schwartz2004) and Toyota's ‘stop the line’ ethos that democratized accountability for quality (Sugimori et al., Reference Sugimori, Kusunoki, Cho and Uchikawa1977) – serve as useful exemplars of employing company-wide design principles to inform conditions that subsequently drove more widespread organizational behaviors.

While incorporating a more principles-based approach into the evidence-based culture of BPP may feel at odds with current norms, there is increasing recognition that complex system conditions in areas such as public health can benefit from mixed-method and iterative modes of evaluating and refining interventions, rather than relying solely on linear models and demonstrations of causality (Rutter et al., Reference Rutter, Savona, Glonti, Bibby, Cummins and Finegood2017; Bradley et al., Reference Bradley, Mansouri, Kee and Garcia2020; Greenhalgh, Reference Greenhalgh2020). This more pragmatic approach has additional precedent in the recent recognition that public policy benefits from a strategic system design mindset (van Buuren et al., Reference van Buuren, Lewis, Guy Peters and Voorberg2020; Schmidt & Stenger, Reference Schmidt and Stenger2021b) and that systems design can contribute a distinct but valuable set of insights to complement more traditional evidence-based approaches, rather than assuming that it must be reduced to ‘design science’ to be of use (Van Aken & Romme, Reference Van Aken, Romme and Rousseau2012; Barzelay, Reference Barzelay2019; Romme & Meijer, Reference Romme and Meijer2020).

Making SPACE for choice infrastructure

While there is no shortage of tactical guidance to help BPP practitioners develop individual behavioral interventions and measure their success (OECD, 2019; Australia et al., Reference Australia, Jungbluth, Zhao, Wright, Plant and Goodwin2021), there are fewer supports to systematically assess, implement, and support the development of improved infrastructural conditions within complex contexts (Alageel et al., Reference Alageel, Gulliford, McDermott and Wright2018). This already difficult challenge is made more so by the significant institutional investment in buy-in, resources, and funding typically required for widespread organizational or system change. As much a complex human systems task as a technical or structural one, implementing choice infrastructure solutions is more akin to change management processes that also tend to demand new behaviors of both system agents and service recipients (Lorenzi & Riley, Reference Lorenzi and Riley2000; Sartori et al., Reference Sartori, Costantini, Ceschi and Tommasi2018).

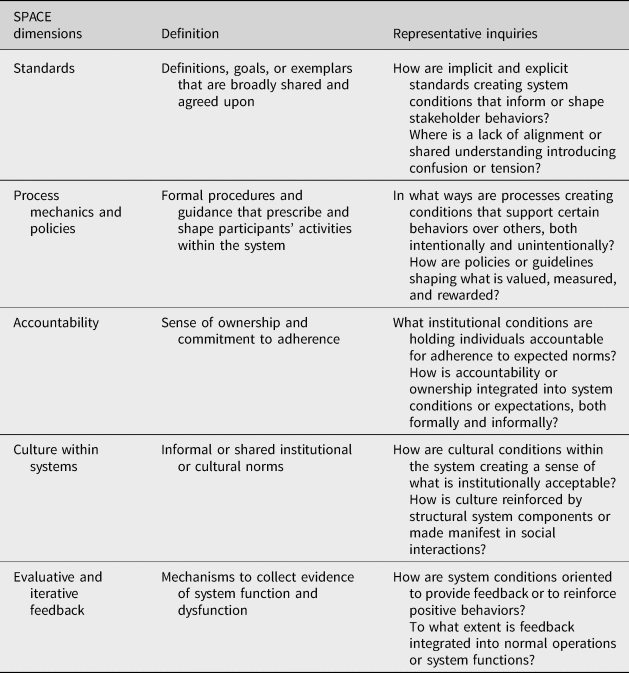

Plentiful change management models already exist (Stouten et al., Reference Stouten, Rousseau and De Cremer2018), yet for the most part, these frameworks tend to focus on abstract change processes (Lewin, Reference Lewin1951; Beckhard, Reference Beckhard1969), directives for leaders (Kotter, Reference Kotter1996), or stakeholder effect (Kubler-Ross, Reference Kubler-Ross1969). Even those identifying organizational targets for change (Peters & Waterman, Reference Peters and Waterman1982) often provide generalized institutional attributes rather than setting new conditions for behavior. The SPACE model (Schmidt et al., Reference Schmidt, Hatch and Curry2021c) can supplement these efforts by helping practitioners analyze how system conditions support behaviors at an institutional scale, rather than solely as individual interventions. Originally created to assess institutional capabilities in the context of scholarship assessment reform, the framework can be employed more broadly in a choice infrastructure context to examine five characteristics – alignment on Standards, Processes and policies, individual Accountability, system Culture, and Evaluative feedback loops – to help policymakers surface gaps in institutional capabilities and identify where infrastructural reform may be necessary to build or improve organizational capacity (Table 2).

Table 2. Dimensions, definitions, and representative inquiries of the SPACE model

The following section articulates how an infrastructural approach using this model might be applied to the policy challenge of encouraging food vendor licensure in the City of Chicago.

A choice infrastructure approach to food vendor licensure in Chicago

Chicago's ethnically diverse and entrepreneurial food culture boasts not only a rich dining heritage but a thriving industry of independent owner-operator street cart food vendors. While in many ways less formal than bricks and mortar establishments, local and state policy regulations still require these vendors to apply for and maintain several licenses related to food preparation and distribution practices as proof of compliance with health and safety requirements (Chicago Small Business Center, 2015, 2017). However, the complicated, expensive, and often onerous procedures of applying for and attaining licenses feed vendor temptations to forego the formal process; as a result, the City forfeits fees that would otherwise contribute to municipal income while some vendors fly under the radar of official oversight, as well as missing opportunities to take advantage of programs designed to support the cultivation of entrepreneurial businesses in Chicago.

Where traditional BPP approaches might direct interventions at vendor behavioral change, deploying framing or compliance nudges to increase appointment attendance and paperwork completion rates, interviews with system stakeholders identified in collaboration with the Chicago Food Policy Action Council (CFPAC) revealed a system characterized by brittle infrastructure and misaligned incentives for behavior (Feng et al., Reference Feng, Impola, Iyengar, Kim, Lee, Mantrala, Pollack, Tan, Tarriba and Ichikawa2018a). These 13 semi-structured qualitative research interviews consisted of 2-h, open-ended generative conversations with 8 vendor owner-operators [V01–V08] and 5 civic consultants specializing in licensure who provided services to applicants [C01–C05], with the intent of eliciting initial insights into challenges faced by Chicago food vendors seeking licensure. The conversations were then transcribed and analyzed using qualitative data theme identification techniques (Ryan & Bernard, Reference Ryan and Bernard2003) to identify directions for further research and subsequently to inform communication and infrastructural design recommendations.

The licensing process touches multiple stakeholders beyond vendors and city clerks – city administrators, Department of Public Health (DPH) employees, and consultants whose job is to shepherd vendors through the licensing process – each of whom has differing priorities and limited insight into areas outside their domain. In addition, food licensing policies change frequently and sometimes unpredictably (‘Every time we went there, they would bring in new requirements. And new requirements, and new requirements’ [V01]), resulting in a complex and shifting set of rules that feed inconsistent interpretations, contradictory guidance (‘It's just a lottery of whoever answers the phone’ [V05]), and difficulties gauging how individual circumstances may deviate from the norm. These inconsistencies are amplified by bureaucrats’ individual decision-making tendencies or administrative styles that render policies different from person to person, resulting in variances in policy as practiced compared to its articulation on paper (Gofen, Reference Gofen2014; Moseley & Thomann, Reference Moseley and Thomann2021).

In addition, equipment and preparation standards that must be approved as part of the licensing process tend to be rigid (Chicago Small Business Center, 2017); while potentially comforting from a public health perspective, this also limits the potential for making judgment calls despite varied preparation, storage, and cultural requirements for different foodstuffs. Finally, the system is characterized by a general lack of feedback and transparency (‘You go in, you fill out the paper, you'd give him a check and that was the last you've heard’ [V05]), which contributes to vendor disorientation and anxiety that is amplified by presumed familiarity with bureaucratic policy language and legalese, disseminated primarily in English despite a target population of largely non-native English speakers (‘… when [applicants] want to be proactive, to find a solution, it stops them. Because everything's in English’ [C03]). In short, this is as much an infrastructural challenge as a behavioral one, in which even the best interventions to address vendor cognitive and behavioral shortcomings would likely result in limited success.

Employing the SPACE model

While differing in terminology, most behavioral design methods and processes to create improved choice architecture follow a similar path of defining problem-solving boundaries, assessing the current state of the challenge, analyzing findings to develop hypotheses, and then constructing and testing solutions on the basis of evidence (Datta & Mullainathan, Reference Datta and Mullainathan2014; OECD, 2019). Although the issues addressed in choice infrastructure problem-solving are performed at the unit level of system conditions rather than behaviors, the process used to uncover challenges in Chicago food vendor licensure was functionally parallel.

Determining the boundaries of the challenge

Framing behavioral challenges typically center on identifying the specific subject and behavior to be addressed, providing both a clear target for intervention development and a concrete, measurable outcome around which to craft evaluation activities (OECD, 2019). By contrast, adopting an infrastructural frame that considers how system interactions, structures, and conditions favor certain behaviors over others might expand beyond optimizing vendor behaviors that increase licensure to also consider how infrastructural conditions impact the behaviors of city clerks and consultants. In addition, attention may be paid to the ways in which infrastructural conditions contribute to a wider set of outcomes, such as how inter-personal and -departmental interactions impact overall system goals for public health, civic equity, and Chicago's reputation as an enviable culinary destination.

While a choice infrastructural frame is intended to consider how revised system conditions and infrastructures can contribute to improved system functionality more broadly, however, it must also remain clear-eyed about limitations of feasibility and authority. In this case, for example, defining an infrastructural unit of analysis would need to resist the urge to include grand plans for redesigning public health oversight or zoning designations that sit outside the reasonable bounds of BPP problem-solving.

Understanding system components and dynamics

Once framing is determined, practitioners can begin to critically assess existing infrastructure and system conditions. This begins by identifying relevant system components and the dynamics between them, giving BPP practitioners insight into where, why, and how individually sensible behaviors may be in conflict (Meadows, Reference Meadows1999; Nold, Reference Nold2021): What actor-agents are present and how do they interact with each other and within the system? Are desired activities and functions well-supported or hampered by current conditions?

In the case of Chicago food licensure, for example, understanding the system would need to consider how stakeholders function or participate in key scenarios across the arc of the licensure process – gathering requirements, completing and processing paperwork, and evaluating physical materials such as food carts – to determine the relevant set of activities, assets, and actors, and how current infrastructures support the dynamics between them. In addition to the use of secondary sources to identify publicly available information, the use of qualitative research such as ethnographic interviews and observations can supply insight into participants’ choice postures and motivations for behavior (Kimbell, Reference Kimbell, Gulier and Moor2009) to enrich an emergent BPP perspective on how infrastructural barriers, both real and construed, may be keeping them from participating effectively.

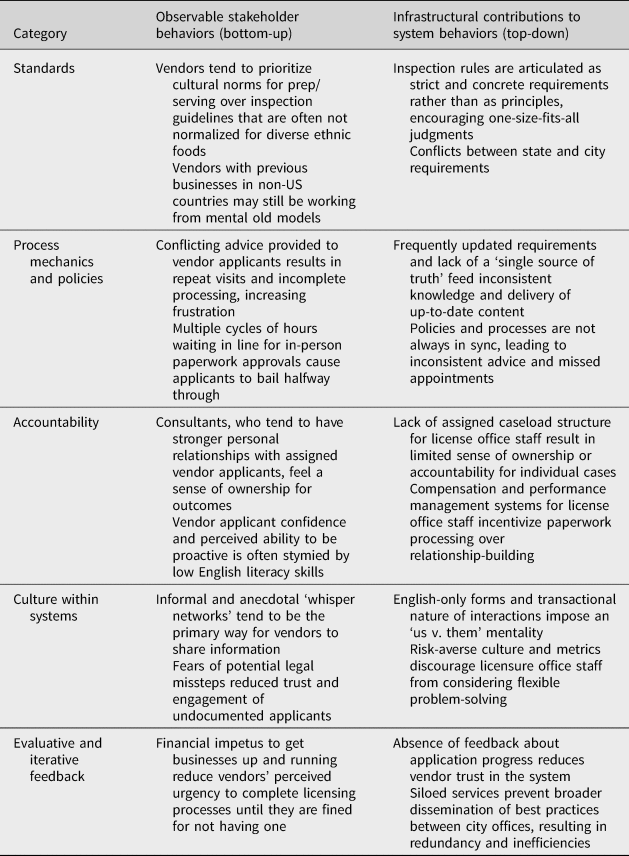

After gathering insight into the ecosystem and its components, applying the SPACE rubric can provide a systematic approach to capturing bottom-up implications of system conditions by assessing how they impact stakeholder behaviors and perspectives, and top-down implications by considering how these conditions may be predisposed to support certain system functions over others. In combination, these observations and insights can prompt practitioners to identify which aspects of existing system infrastructure will need to be maintained, expanded, modified, or rethought altogether (Table 3).

Table 3. Illustrative application of the SPACE model to categorize and capture bottom-up and top-down aspects of the current food licensure system, sourced from stakeholder interviews.

While the SPACE framework encourages structured information-gathering, however, the reality of systems is not nearly so tidy. This suggests that practitioners can benefit from seeing connections and patterns between data points and insights rather than relying on efforts to solve them individually. For example, research indicated that the lack of a single source of truth for current requirements (‘… she said, “No, you can't keep this at home.” I said, “What?” so then she spoke to her supervisor, and the supervisor arrived and said, “Yes, she can store the cart at home.”’ [V07]) contributed to several infrastructural challenges, reinforcing a system that is at once highly stringent and inflexible (Standards, Process mechanics and policies) but also mercurial and unreliable due to the distributed ownership of individual cases and tendency for city staff to prioritize paperwork over people (Accountability, Culture within systems).

Analyzing the implications of current conditions

Like BPP processes to improve choice architecture that analyzes choice situations to identify which strategies to employ, analysis in a choice infrastructure context examines current underlying system conditions to discern how they may need to be adjusted or reconfigured to support user behaviors and overall system functionality. Where traditional BPP problem-solving methods typically focus on key user drop-off points to inform solutions (OECD, 2019), however, a choice infrastructure perspective might instead examine system affordances to expose linear and non-linear implications of underlying conditions: Where is existing infrastructure sufficiently robust and where is it deficient in supporting desirable behaviors? How are certain behaviors or system functions supported over others at micro and macro scales due to a surfeit or lack of resources and structural support? How is power concentrated and reinforced by structures, policies, and policies?

Analyzing the situation from an infrastructural standpoint helps focus attention on how conditions may support or fail to accommodate intended system beneficiaries, indicating gaps or misalignments that can indicate the potentially inequitable distribution of resources. For example, evidence of infrastructural deficits surfaced in findings that despite consultants’ keen insight and process expertise (‘I think every food entrepreneur needs a Sarah, a consultant that knows what to look for and knows how to set things up’ [V02]), limitations on their availability forced applicants unable to access consultant services to cobble together best practices and paths forward on their own, putting them – and the system goal of achieving broader overall license compliance – at a clear disadvantage. In this case, applying the SPACE model could indicate the need to address Standards (to address the variability of ‘need to know’ information), Process mechanics and policies (to identify patterns in who has access to consultant expertise or provide alternatives), and Accountability (to provide specifics of vendor responsibility in cases when consultants are not available, to even the playing field) to achieve greater parity.

Identifying infrastructural sources of control or power at an early stage of problem-solving can also further illuminate how certain priorities or principles are holding current systems in place. Positioning policy and organizational structures as technical challenges that can be analyzed and scientifically solved ignores that stable systems may persist less due to their inherently rational nature than to power dynamics, and further that stable systems are not necessarily healthy ones (Fabinyi et al., Reference Fabinyi, Evans and Foale2014; Lewis et al., Reference Lewis, McGann and Blomkamp2020). This can provide a perspective on who or what might be resistant to changes in the status quo as well as clues as to perverse or contradictory system tensions, such as where structures and incentives designed to emphasize tactical efficiency (e.g., forms designed for automated data entry rather than applicant comprehension; minimum target thresholds for vendor clients seen per day) that benefit certain system constituencies might come at the expense of user experience or overall system effectiveness (e.g., applicants struggle to fill out forms accurately; appointments are too short to fully understand next steps). Practitioners can capture these dynamics, relationships, and assets in the form of system maps (Nogueira et al., Reference Nogueira, Ashton and Teixeira2019) to surface key points of leverage and underutilized or overextended resources. In parallel, behavioral mapping activities, such as those employed by the Behavioral Insights Team (BIT), the US Office of Evaluation Sciences, and the Center for Advanced Hindsight (Office of Evaluation Standards, 2021; White & Trower, Reference White and Trower2021), can provide an end-to-end view of relevant activities to help policymakers analyze how existing infrastructures might be reused or repurposed to support desired behaviors, and highlight where new capabilities may need to be configured.

Crafting new conditions to support behaviors and interventions

After analysis, work turns to proposing potential new infrastructural conditions that can support desirable system functions and specific behavioral interventions: What infrastructural changes are most critical to addressing identified shortcomings, and which are lower priority? How can unintended consequences or new complexities resulting from revised conditions be minimized or avoided?

Upon identifying critical points of intervention, the SPACE framework or similar tools can be employed to propose concrete solutions for both transforming internal system functions and improving user- or recipient-facing service design (Burns et al., Reference Burns, Cottam, Vanstone and Winhall2006). Unlike choice architecture, which is primarily used to course-correct for previously identified behavioral shortfalls, activating existing but underutilized infrastructure or introducing new infrastructural conditions can also lead to the creation of entirely new forms of public value (Bryson & George, Reference Bryson and George2020). For the Chicago food licensure context, for example, the recognition that a lack of process transparency was a prime reason for vendor drop-out might suggest that the ability to track applications and improve insight into system mechanics (Process mechanics and policies; Evaluative and Iterative feedback) could support vendors’ needs while also enabling city clerks’ ability to distinguish true outlier situations from the norm more readily, contributing to greater system efficiency.

However, paying keen attention to the inadvertent introduction of possible downstream or cross-system effects is perhaps even more essential when adjusting system conditions and choice infrastructure than when introducing new choice architecture, given its potential for widespread system disruption (Emery et al., Reference Emery, de Molière, Lang, Nicolson and Prince2021; Schmidt & Stenger, Reference Schmidt and Stenger2021a). For example, research indicated that inspections were a particularly stressful part of licensing processes for vendors, in large part because of their erratic nature and inconsistent application (‘the individual person you're dealing with may have a different read on some of these rules or catch something that no one else caught’ [C04]) and their potential for derailing progress (‘Because as soon as you pay the license, that triggers [an inspection] and if you fail the inspection then you don't get another chance. You have to go reapply’ [V06]). While infrastructural advances to improve transparency into the range of what is acceptable (Standards) and more guidance to reduce chances of inspection failure (Evaluative and Iterative feedback) would undeniably be of use, effective system solutions would also require identifying and addressing perverse incentives, such as metrics that rewarded inspectors for hitting a quota of penalties that might encourage them to mete out unjustified inspection failures.

This raises the additional need to consider countervailing forces and incentives that reward maintaining current systems, despite their recognizable flaws, over improved ones. Even when barriers and capability gaps are well known and unsurprising in theory, workarounds that have become normalized and institutional and personal tendencies toward status quo bias can render them overly familiar, allowing system flaws to remain ‘hidden in plain sight.’ At the same time, the costs – financial and otherwise – of disrupting even recognizably flawed but functional systems can interfere with efforts to improve them. As a result, correcting infrastructural challenges may require not just identifying flaws, but building the case for prioritizing change, and rousing the resources required to enact those changes.

Measuring and evaluating success

While the evidence of efficacy provided by RCTs or field experiments may be highly persuasive in justifying implementation and further investment in choice infrastructural recommendations, these evaluative mechanisms may also be less equipped to evaluate success in complex conditions with multiple independent variables, longitudinal outcomes, and high levels of future uncertainty (Spotswood & Marsh, Reference Spotswood, Marsh and Spotswood2016). In addition, system goals are by nature diverse. In the case of Chicago food licensure, for example, while increasing the number of licenses acquired is an important measure of success, less tangible outcomes such as city vibrancy and the cultivation of a world-class food scene are equally desirable on a broader system scale. Given that applied behavioral science has predicated itself on a shared belief in scientific instruments and experimentation, infrastructural challenges that require alternative mechanisms to evaluate success may be seen as ill-fitting or unworthy of BPP inquiry (Straßheim, Reference Straßheim2021).

The effective evaluation of choice infrastructure may therefore need to combine several approaches that combine evidence of measurable success with evidence for potential course-corrections (Lewis et al., Reference Lewis, McGann and Blomkamp2020): for the former, by designating measures for individual improvements that can be captured by more traditional evidence-based mechanisms, and for the latter, through a set of characteristics – both qualitative and quantitative – that capture attributes of desired system outcomes that can indicate relative progress toward longer-term goals (Schmidt & Stenger, Reference Schmidt and Stenger2021b). Measuring and determining the efficacy of new choice infrastructure may, for example, include the use of indirect modes of evaluation in the form of ‘weak signals’ (Ansoff, Reference Ansoff1975), feedback loops, and leading metrics to supplement more traditional lagging ones (Schmidt & Stenger, Reference Schmidt and Stenger2021b) and prototyping solutions on smaller scales, less to formally evaluate them than to identify opportunities for improvement (Waardenburg et al., Reference Waardenburg, Groenleer and De Jong2020).

This approach is bolstered by increasing skepticism that a definitive solution can realistically be achieved in the context of complex adaptive systems, or that achieving closure in these environments is even possible (Rittel & Webber, Reference Rittel and Webber1973; Huppatz, Reference Huppatz2015; Perera, Reference Perera2020). Instead, the high variability of cases and need for flexibility suggests that implementing choice infrastructure may perhaps be better seen as a process of continual refinement – more a process of re-solution than solution – rather than as a singular, one and done implantation of policy.

Potential contexts of application

Many policy interventions and infrastructures, such as public health interventions to encourage flu vaccination or civic engagement such as increasing voter registration, occur in less bounded institutional environments with less direct oversight over infrastructural mechanisms than the scenario of food licensure just described. The question might therefore naturally arise whether choice infrastructural concerns are only relevant to highly prescribed or top-down situations and contexts. However, the recognition that moving beyond interventions to designing conditions is valuable in a variety of other contexts suggests that improving choice infrastructure should not be unduly limited to such circumstances.

For example, recent field experiments proposing a range of nudges to increase uptake of the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) failed to achieve measurable traction, resulting in speculations that greater infrastructural issues related to tax filing in the low-income populations targeted for the program presented barriers too significant to overcome with behavioral interventions alone (Linos et al., Reference Linos, Prohofsky, Ramesh, Rothstein and Unrathforthcoming). Bringing COVID-19 vaccines to individuals with the real or perceived inability to seek out and attend appointments to receive the shots, either at work on at community events (Artiga & Hamel, Reference Artiga and Hamel2021) could also be seen as a choice infrastructural solution to a behavioral challenge given its focus on connecting previously disconnected assets and transferring the onus of behavioral change from individuals to broader system capabilities. And efforts to encourage (or stymie) getting out the vote that relies on the introduction (or removal) of infrastructure in the form of drop-off boxes, support for mail-in ballots, opt-out and ‘motor-voter’ registration, and access to voting during a wide range of hours to accommodate working schedules similarly qualify as infrastructural approaches (Carnegie Corporation of New York, 2019).

This is also not to say that BPP alone should be responsible for the design and maintenance of infrastructural supports for behavior. For example, while solving for the unbanked may benefit from greater attention to perceived infrastructural barriers to entry at an institutional level (Bertrand et al., Reference Bertrand, Mullainathan and Shafir2006), and public policy can address certain forms of regulatory or system access constraints, other non-policy innovations – such as alternative products and services to support unbanked populations – may present new opportunities to better serve these populations (Loufield et al., Reference Loufield, Ferenzy and Johnson2018).

Potential implications of an infrastructural approach

Developing choice infrastructure solutions to augment choice architecture interventions will likely require interrogating several BPP conventions, including perceptions of policy as an impartial mechanism for change and norms of who contributes to crafting policy. This is of particular importance given that policymakers and bureaucrats are typically not recipients of the policies they create or carry out, nor are they always aware of their recipients’ personal contexts. Methodologies that address infrastructural issues must also combat the well-established perception of nudging – and BPP more broadly – as a relatively low-cost solution that does not require disrupting or uprooting more deeply embedded systems and functions.

BPP is never inherently neutral; for all its emphasis on addressing bounded rationality, public policy itself is limited by bounded conceptions of assumed norms and default values, what constitutes ‘preferred’ behaviors, and what is deemed worthy of correction to begin with (Schön & Rein, Reference Schön and Rein1994). It is already widely recognized that policymakers’ biases, personal preferences, and distance from the policies for which they are responsible can impact the perceived relevance or equity of choice architecture (Lang & Rayner, Reference Lang and Rayner2012; Moseley & Thomann, Reference Moseley and Thomann2021).

Designing choice infrastructure faces the same quandary, on the one hand asserting which functions, audiences, and activities should be supported over others (Star & Ruhleder, Reference Star and Ruhleder1997), while also navigating the fact that biases embedded within systems tend to perpetuate the norms and values of those who created them (Winner, Reference Winner1980; Feitsma & Whitehead, Reference Feitsma and Whitehead2019). Proposals that encourage good health through prompts to visit gyms and health clubs, for example, may fail to question infrastructural inequities such as the lack of easy access to these facilities or the prohibitive costs of gym membership that can exclude certain communities or populations (Forberger et al., Reference Forberger, Reisch, Kampfmann and Zeeb2019). Clearly, then, any entreaty to design new infrastructural conditions thus demands paying as much attention to policy nudgers as to ‘nudgees’ (Trenchard-Mabere, Reference Trenchard-Mabere and Spotswood2016), and designing solutions that support front-line service providers whose behaviors are also shaped by the underlying institutional conditions in which they work (Moseley & Thomann, Reference Moseley and Thomann2021).

Recent work in participatory or co-design practices has attempted to address these kinds of embedded top-down biases by expanding notions of who should contribute to the design of public policy (Jones, Reference Jones, Jones and Kijima2018; John, Reference John, Peters and Zittoun2016). While some have posited that behavioral methodology and co-design are essentially contradictory, and thus may result in cognitive dissonance on the part of policymakers and reduced trust in interventions on the part of recipients (Einfeld & Blomkamp, Reference Einfeld and Blomkamp2021), this position perhaps hews too narrowly to equating BPP with nudging and choice architectural norms. Employing participatory design strategies in a choice infrastructural context can insert invaluable first-hand knowledge of system functions and personal motivators, and a heightened awareness of the ways in which personal context, barriers, and beliefs inform how ‘nudges’ are perceived or adopted (Hauser et al., Reference Hauser, Gino and Norton2018). It also reveals a critically important understanding of users’ incoming operational mental models, which can highlight situations in which proposed policies may cause significant frustration if misaligned with actual system functions. In addition, design-informed approaches such as collaborative governance have shown potential to help practitioners institute change in civic settings that may otherwise resist efforts due to stakeholder inertia and a desire to control power dynamics, in part through creating conditions that are conducive to supporting this kind of design problem-solving (Ansell & Torfing, Reference Ansell, Torfing, Ansell and Torfing2014; Bryson et al., Reference Bryson, Crosby and Seo2020; Waardenburg et al., Reference Waardenburg, Groenleer and De Jong2020), which is itself a form of choice infrastructure.

Finally, involving end recipients in framing problems should be seen not merely as an opportunity to improve solutions. Rather, design-informed and cross-boundary collaborations that recognize the distinct contributions of policymakers, bureaucrats, and impacted publics can contribute to several critical BPP issues (Ansell & Torfing, Reference Ansell, Torfing, Ansell and Torfing2014): expanding the nature of evidence that informs hypothesis development (Schmidt, Reference Schmidt, Boess, Cheung and Cain2020); transforming efforts from stand-alone interventions to institutional capacity, in which system stakeholders can assess and address changing conditions even after policymakers are gone (Burns et al., Reference Burns, Cottam, Vanstone and Winhall2006; Sangiorgi, Reference Sangiorgi2011); and – perhaps most importantly – helping inform perspectives on what is worthy of being addressed (Schön & Rein, Reference Schön and Rein1994).

Conclusion

Expanding on the familiar notion of choice architecture to embrace ‘choice infrastructure,’ or the design of underlying systemic armatures that support choice-making environments, could be seen as both necessary and a natural advance for BPP. By focusing on choice conditions of systems that support desired behavioral change, rather than solely on individual interventions, an infrastructural approach is positioned to fortify long-term, integrated behavioral change flexibly while also maintaining consistency. Perhaps most importantly, embracing an infrastructural lens promises to increase attention on the values and biases that are often embedded within systems, promoting a more equitable distribution of access and assets.

At the same time, BPP's success in addressing ‘nudgeable’ challenges has proven to be both a blessing and a curse, at once providing clarity of purpose while also limiting potential impact by narrowly classifying what counts as a problem ripe for BPP problem-solving (Schmidt & Stenger, Reference Schmidt and Stenger2021b). Further developing the case for choice infrastructure's value within BPP will therefore require overcoming disciplinary norms that presume that individual interventions for behavior change are the only challenges appropriate for policymaker and practitioner attention. To some, the loosening of traditional BPP disciplinary boundaries that will be required to address choice infrastructure may feel too great or too risky.

However, this may partly reflect the common tendency for disciplinary methodologies to shift from tools to gatekeepers, bounding what are considered viable subjects for attention, how these subjects are explored and tested, whose problem-solving expertise is deemed credible, and whose values are considered normal (Straßheim, Reference Straßheim2021). Championing choice infrastructure might also not be the stretch it initially appears to be. The broader notion of economies as flexible yet consistent mechanisms to support systems of exchange is already embedded in the term ‘behavioral economics.’ Positioning choice infrastructure in a similar light – as a transformative enabler of system exchanges to support both individual behaviors and overall system robustness (Sangiorgi, Reference Sangiorgi2011) – suggests that choice infrastructure solutions can provide the backbone for a new kind of ‘behavioral economy,’ designed to support sustainable and system-level choice, judgment, and decision-making across diverse stakeholders and contexts.

Resistance to the complexities inherent in embracing systems and choice infrastructure design is also eerily parallel to the cases of ALCOA and Toyota, in which the principles that ultimately drove their success – safety and quality, respectively – broke from the norm, and were initially met with discomfort, confusion, and disparagement. This is perhaps not a coincidence, and also an opportunity; that taking a choice infrastructural lens to BPP may raise similar objections is perhaps less indicative of the preposterousness of the proposal than of systems’ tendencies to maximize and maintain their current stability, functionality, and integrity at the expense of change.

Competing interest

The author(s) declare none.