Introduction

The prevalence of sexual assault on college campuses, and its destructive effects on students and the overall college environment, is now recognized by a broad coalition of policymakers, researchers and educators (e.g., Koss et al., Reference Koss, Gidycz and Wisniewski1987; Fisher et al., Reference Fisher, Daigle and Cullen2009; Hostler, Reference Hostler2014; White House Council on Women and Girls, 2014; cf. U.S. Department of Education, 2017). Sexual assault threatens the safety, academic success and overall well-being of a substantial proportion of college students. For example, a student who is sexually assaulted is more likely to drop classes, move residences and seek psychological counseling (Krebs et al., Reference Krebs, Lindquist, Warner, Fisher and Martin2007; see also Brener et al., Reference Brener, McMahon, Warren and Douglas1999; Gidycz et al., Reference Gidycz, Orchowski, King and Rich2008; Moylan & Javorka, Reference Moylan and Javorka2020).

Sexual assault broadly refers to any sexual activity involving a person who does not provide consent or cannot provide consent (due to alcohol, drugs or other causes of incapacitation). By this definition, women between the ages of 18–25 are at the greatest risk for being sexually assaulted (Sinozich & Langton, Reference Sinozich and Langton2014). Among women enrolled in an undergraduate college institution, 20–25% are expected to experience sexual assault (Krebs et al., Reference Krebs, Lindquist, Berzofsky, Shook-Sa, Peterson, Planty and Widico Stroop2016).

Currently, bystander intervention is the primary type of intervention programming used to prevent sexual assault. Sexual assault bystander programs come in different forms, but their common strategy is to educate students about situations in which sexual assault may occur, and to encourage students to intervene in a safe manner when they believe that sexual assault may happen or is happening (e.g., Moynihan & Banyard, Reference Moynihan and Banyard2008; Coker et al., Reference Coker, Cook-Craig, Williams, Fisher, Clear, Garcia and Hegge2011). In a recent review of college sexual assault trainings, 94% contained at least one component of bystander training (34 of 36 programs; listed on cultureofrespect.org). Due to the prevalence of bystander intervention training, it is important to understand the theoretical justification that is most commonly used for this type of intervention.

The current monopoly of bystander trainings on college interventions is likely due to the theoretical perspective advanced by the clinical psychology scholar David Lisak and his colleagues. Although bystander intervention can be justified by other theoretical perspectives (see Banyard et al., Reference Banyard, Plante and Moynihan2004), the current predominant justification for it is the serial rapist model (Lisak & Miller, Reference Lisak and Miller2002). According to the serial rapist model, a small number of male students, who are fundamentally different from their peers on college campuses, are responsible for the vast majority of campus rapes and other types of sexual assault (e.g., Lisak, Reference Lisak2004, Reference Lisak2011). Lisak and colleagues’ claims are based on a cross-sectional self-report survey of males ages 18–71, in which 6.4% of respondents reported acts of attempting or completing sexual intercourse or oral sex without their partner’s consent (Lisak & Miller, Reference Lisak and Miller2002). A portion of this group (4% of the overall sample) reported multiple acts each; Lisak and Miller estimated that this small group of reporters were responsible for the majority (91%) of all sexual assaults reported in the survey. Lisak labels these repeat offenders “serial rapists” and characterizes them as planning and premeditating their attacks (Lisak, Reference Lisak2011), scoring lower than average on empathy (Lisak & Ivan, Reference Lisak and Ivan1995),Footnote 1 and higher than average on hostility towards women (Lisak & Roth, Reference Lisak and Roth1988).

Citing these data, Lisak has been a vocal promoter of bystander interventions as a lecturer and consultant to colleges across the United States. “Rather than focusing prevention efforts on the rapists, it would seem far more effective to focus those efforts on the far more numerous bystanders” (Lisak, Reference Lisak2011: 56). In other words, Lisak believes that because serial rapists are too difficult to reform or even to identify, interventions should instead change the behavior of bystanders.

However, Lisak and Miller’s (Reference Lisak and Miller2002) data purporting that serial rapists are responsible for the majority of sexual assaults on campus have been disputed (Swartout et al., Reference Swartout, Koss, White, Thompson, Abbey and Bellis2015; Utt, Reference Utt2016). On methodological grounds, researchers have pointed out that the dataset involves community members and not only students (despite explicit extrapolation to a college sample), asks respondents to report assaults committed before as well as during college, and does not establish whether multiple acts constitute multiple incidents or multiple acts within the same incident, or whether repeated acts involve the same person or different people (see also Singal, Reference Singal2015; Thomson-DeVeaux, Reference Thomson-DeVeaux2015). Furthermore, the data were not available upon request (LeFauve, Reference LeFauve2015).

By contrast, two recent large-sample longitudinal studies of male-identified college undergraduates do not find evidence that serial rapists account for most assaults on college campuses (Swartout et al., Reference Swartout, Koss, White, Thompson, Abbey and Bellis2015). Importantly, these studies find that approximately twice as many men report rape as the respondents in Lisak and Miller’s (Reference Lisak and Miller2002) study, and do not do so in a consistent fashion compatible with a serial rapist model of sexual assault. While a substantial number of men report more than one rape, their temporal patterns of assault contradict the simplistic idea that they are “serial” perpetrators.

Swartout and colleagues conclude, “[a]lthough the serial rapist assumption is widely taken as fact by politicians and the popular press, it appears to be premised on a single source” (Reference Swartout, Koss, White, Thompson, Abbey and Bellis2015: 1149), referring to the Lisak and Miller (Reference Lisak and Miller2002) paper. They make a different recommendation regarding bystander programming: “Exclusive emphasis on serial predation to guide risk identification, judicial response, and rape-prevention programs is misguided … [we caution] against a uniform approach to high school and college rape response and prevention” (1148, 1153). It is beyond the scope of this paper to adjudicate among different models of sexual assault on campus and the prevention efforts they recommend. Instead, we ask – given the paucity of evidence to support it – why does the serial rapist model persist in the policy marketplace of ideas? In particular, we ask what psychological factors might drive an individual’s subscription to the serial rapist model and what types of beliefs or ways of seeing the world are most compatible with this model.

The serial rapist model and the bystander intervention it recommends was received by university administrations and by the public with great interest and enthusiasm, and its appeal has endured. The popularity of the serial rapist model is, from one perspective, quite surprising. The model is endorsed by university administrators and advocates, many of them sophisticated social scientists, despite the fact that the serial rapist model was based on a single disputed paper, and that more recent data presents a different picture of campus sexual assault. The need for bystander trainings are a primary focus in college campus sexual assault prevention programming (e.g., itsonus.org; cultureofrespect.org; DeGue et al., Reference DeGue, Valle, Holt, Massetti, Matjasko and Tharp2014).

From a different perspective, adherence to the serial rapist model among policy makers and members of the public is not particularly surprising. Scholars interested in the policy marketplace of ideas, and specifically in the relationship between policy and evaluation, have long observed that certain narratives about social problems are sticky, and that policy choices are extremely slow to change (e.g., Weiss, Reference Weiss1977). One of the reasons this occurs, according to this scholarship, is that research is often used to legitimate policymakers’ and the public’s pre-existing ideas, rather than to change them.

Lisak’s serial rapist model presents an explanation of sexual assault on college campuses that may satisfy many people’s pre-existing worldviews. By worldviews, we mean a person’s general ideas about how the world works and how people relate to one another. People may not only believe, but need to believe in these worldviews to make sense of their lives; these worldviews can help to manage uncertainty, reduce anxiety and promote social ties (Hennes et al., Reference Hennes, Nam, Stern and Jost2012). For example, to varying degrees people espouse a belief in a just world (Lerner & Miller, Reference Lerner and Miller1978), a fair political system (Jost & Banaji, Reference Jost and Banaji1994), and in valid hierarchies (Pratto et al., Reference Pratto, Sidanius, Stallworth and Malle1994), as well as a preference for neat and simple accounts of the world (or “need for closure”; Webster & Kruglanski, Reference Webster and Kruglanski1994), and of other people (via essentialized views of their traits; Bastian & Haslam, Reference Bastian and Haslam2006).

Why might these worldviews be consistent with an endorsement of the serial rapist model? Consistent with these worldviews, the serial rapist model clearly distinguishes between bad and good people, and implies a simple story of justice by identifying who is a villain, who is a victim and whose behavior we should change. Instead of problematizing human nature, or re-examining ourselves, our social group, and the societal system, the serial rapist model preserves our faith in humanity, ourselves and our social groups, and in our social system and its hierarchies, because sexual assault perpetrators are fundamentally abnormal and different from ourselves.

We hypothesize that the serial rapist model may appeal to people’s pre-existing worldviews that cohere around ideas of a just and good status quo, and a preference for simple stories. While all people endorse these views to a certain extent, important individual differences emerge in the strength of these needs and beliefs. Individuals whose worldviews are stronger will be more likely to adopt accounts that fit with, or further justify, their worldviews (Pratto et al., Reference Pratto, Sidanius, Stallworth and Malle1994; Chen & Tyler, Reference Chen, Tyler, Lee-Chai and Bargh2001; Glick & Fiske, Reference Glick and Fiske2001; Quist & Resendez, Reference Quist and Resendez2002; Kay & Jost, Reference Kay and Jost2003). As a result, we predict that the serial rapist model may appeal widely, but will resonate more with some people. Specifically, the serial rapist model’s account of rapists as “bad” people distinct from “normal” people would satisfy the individuals’ need for closure (Webster & Kruglanski, Reference Webster and Kruglanski1994), and reinforce the belief that people have a core essence that defines them (Bastian & Haslam, Reference Bastian and Haslam2006). Also, people with relatively stronger beliefs in a just world (Lerner & Miller, Reference Lerner and Miller1978), a fair system (Jost & Banaji, Reference Jost and Banaji1994), and a valid hierarchy (Pratto et al., Reference Pratto, Sidanius, Stallworth and Malle1994) should also be more attracted to an explanation in which bad people are the ones who do bad things without calling into question the larger system and existing hierarchy of individuals and institutions in that society. Our predictions are anticipated by similar work showing, for example, that people who believe strongly in the social dominance of some groups over others also endorse the protestant work ethic as an explanation for the unequal distribution of wealth in society (Pratto et al., Reference Pratto, Sidanius, Stallworth and Malle1994).

In the current set of studies, we ask two linked questions: What is the psychological appeal of the serial rapist model as an explanation for sexual assault perpetration on college campuses? Are there particular worldviews that resonate with justice vs evil, black vs white narrative presented by the serial rapist model? We hypothesize the serial rapist model will be more strongly endorsed by people who also endorse worldviews which cohere around ideas of a just and good status quo, and a preference for simple stories.

We conducted two surveys, one with a convenience and one with a nationally representative U.S. sample, to assess the link between endorsement of the serial rapist model and worldviews like a belief in a just world, social dominance and need for closure. At stake here are questions about what drives our desire to see a policy issue in a particular way, and how to identify its solutions.

Study 1

Study 1 measured whether individuals who are high in need for closure (Webster & Kruglanski, Reference Webster and Kruglanski1994), essentialism (Bastian & Haslam, Reference Bastian and Haslam2006), belief in a just world (Lerner & Miller, Reference Lerner and Miller1978), social dominance orientation (Sidanius & Pratto, Reference Sidanius and Pratto2001) and system justification (Jost et al., Reference Jost, Banaji and Nosek2004) were more likely to support the serial rapist model. To test whether endorsement of the serial rapist model was specific to our hypothesized constructs, we tested for discriminant validity in two ways. First, we measured psychological constructs that we hypothesized would not be related to the serial rapist model as they do not cohere around ideas of a just and good status quo, and a preference for simple stories. These were: belief in free will (Rakos et al., Reference Rakos, Laurene, Skala and Slane2008), moral beliefs (Graham et al., Reference Graham, Haidt and Nosek2009) and need to belong (Baumeister & Leary, Reference Baumeister and Leary1995). Second, we described an alternate, but compatible “rape culture” model of sexual assault to respondents, one that points to many factors that contribute to assault such as demeaning attitudes toward women, power differentials and alcohol. A model of sexual assault framed around a culture of rape is not a logical opposite of, or even incompatible with, a serial rapist model. Thus, we did not predict that endorsement of the rape culture model would negatively correlate with the worldviews predicted to correlate with the serial rapist model. Because the rape culture model is distinct, we hypothesized that the worldviews predicting endorsement of the serial rapist model would not similarly predict endorsement of the rape culture model; we pre-registered no specific predictions about the relationship between the rape culture model and measured worldviews. In the survey, we labeled the serial rapist model as “Bad Apples” and the rape culture model as “Bad Climate,” to avoid any preconceived notions respondents might have about either model.

We report how we determined our sample size, all data exclusions (if any), all manipulations, and all measures in the study. We pre-registered all survey items, item groupings and analyses. All pre-registrations, materials, code and data available at the Open Science Framework (osf.io/guafe).

Methods

Participants and design

In the winter of 2017, we recruited 501 participants on Amazon’s Mechanical Turk, or mTurk (258 males, 240 females, 3 “other gender,” recoded as missing for gender analyses due to small numbers). Participants ranged in age from 19 to 77 (M = 37.71, SD = 12.59). All participants saw all questions in our correlational design, and all participants’ responses were included for analysis. We included one true or false comprehension question for each descriptive model of sexual assault (i.e., serial rapist and rape culture). Of 501 participants, 37 failed the comprehension question regarding the serial rapist model, and 47 failed the rape culture comprehension question. Only five failed both. All following analyses include all participants; results remain the same when participants who failed comprehension questions are excluded unless otherwise noted. For the full survey, including the full text of comprehension questions see our OSF page.

Materials and procedure

After informed consent, all participants completed scales measuring their individual need for closure (Roets & Van Hiel, Reference Roets and Van Hiel2011), belief in essentialism (Bastian & Haslam, Reference Bastian and Haslam2006), belief in a just world (Lucas et al., Reference Lucas, Zhdanova and Alexander2011), social dominance orientation (Jost & Thompson, Reference Jost and Thompson2000), level of system justification (Kay & Jost, Reference Kay and Jost2003), belief in free will (Rakos et al., Reference Rakos, Laurene, Skala and Slane2008), endorsement of the “moral foundations” (Graham et al., Reference Graham, Haidt and Nosek2009) and need to belong (Leary & Baumeister, Reference Leary and Baumeister1995), as well as three items used to measure political orientation. Where validated scales exceeded 14 questions, we went to the original publication of the scale and chose the highest loading factors to minimize time commitment for participants.Footnote 2 We randomized the ordering of the scales across respondents. After these individual difference measures, participants read about both the “Bad Apples” (i.e., serial rapist) and the “Bad Climate” (i.e., rape culture) explanation for sexual assault (ordered randomly across respondents). After reading about each explanation for campus sexual assault, participants answered a true or false question testing their comprehension of the explanation, and rated how well they thought the model correctly explained sexual assault on college campuses. Finally, participants answered demographic questions about their race, gender, age, income, religion and education, and whether they were currently attending a university.

Worldviews predicted to relate to the serial rapist model

We predicted that need for closure, essentialism, belief in a just world, social dominance orientation and system justification would each relate to endorsement of the serial rapist model. A representative item from the five-item need for closure scale is: “I dislike unpredictable situations” (1 = completely disagree to 5 = completely agree). A representative item from the four-item essentialism scale is “The kind of person someone is, is clearly defined; they either are a certain kind of person or they are not” (1 = strongly disagree to 6 = strongly agree). A representative item from the 4-item belief in a just world scale is “Other people usually receive the outcomes they deserve” (1 = strongly disagree to 7 = strongly agree). A representative item from the four-item social dominance orientation scale is “Sometimes other groups must be kept in their place” (1 = very negative to 7 = very positive). A representative item from the four-item system justification scale is “In general, the American system operates as it should” (1 = strongly disagree to 9 = strongly agree). All scales obtained a Cronbach’s alpha above 0.79.

Worldviews predicted to not relate to the serial rapist model

We predicted that need to belong, moral foundations and belief in free will, would not relate to endorsement of the serial rapist model. A representative item from the four-item need to belong will scale is “I need to feel that there are people I can turn to in times of need” (1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree). A representative item from the 10-item moral foundations scale, measuring the foundation of harm, is “When you decide whether something is right or wrong, how relevant is whether or not someone cared for someone weak or vulnerable?” (1 = not at all relevant to 9 = extremely relevant). These items are measured for each of the five foundations (harm, fairness, authority, loyalty and purity). A representative item from the four-item belief in free will scale is “Human beings actively choose their actions and are responsible for the consequences of their actions” (1 = strongly disagree to 6 = strongly agree). All scales obtained a Cronbach’s alpha above 0.60, except belief in free will (α = 0.54).

Political orientation. Three 9-point questions measured political orientation (Cronbach’s (α = 0.93)): “Where on the following scale of political orientation would you place yourself (overall, in general)?”, “In terms of social and cultural issues, how liberal or conservative are you?” and “In terms of economic issues, how liberal or conservative are you?” (1 = extremely liberal to 9 = extremely conservative).

Descriptions of serial rapist and rape culture models of sexual assault. Before reading either description participants read:

Now we are going to ask you some questions about a much-discussed social issue: high rates of sexual assault on college campuses in the U.S. You will read two explanations that have been offered to explain the high rates of sexual assault: The “Bad Apples” explanation: a small amount of students are responsible for most of the assault on campus; The “Bad Climate” explanation: many students commit assault on campus. After you read the Bad Apples and Bad Climate explanations, we will ask you your opinions about each one.

When they read about the serial rapist model, they read the following description, under the header “Bad Apples”:

One explanation for the high rates of sexual assault on college campus is that the majority of assaults are perpetrated by a small group of “bad apples” or “predators” – young men who each commit multiple rapes each. These young men use strategies like: intentionally giving women too much to drink, separating women from their friends, identifying women who are too intoxicated to consent, using sufficient force or threats to coerce victims into submission This small group of serial rapists can be distinguished from the majority of men on campuses, who are not involved in sexual assault.

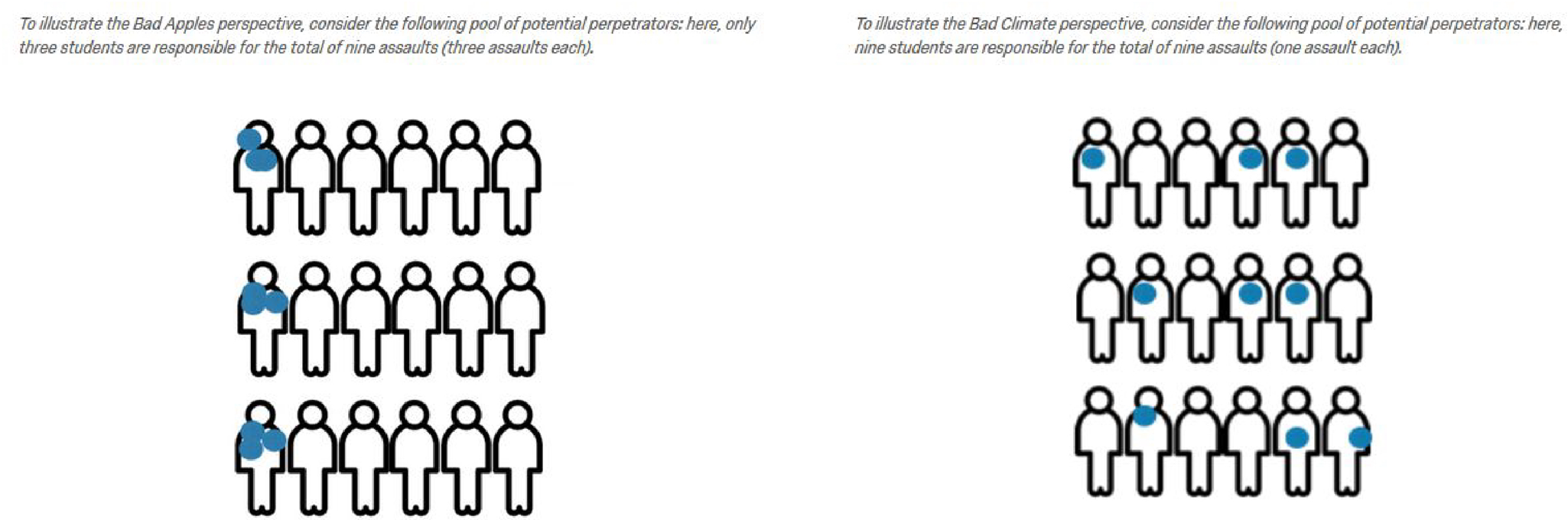

This was followed by an illustration (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Illustrations for “Bad Apples” and “Bad Climate” descriptions.

When they read about the rape culture model, they read the following description, under the header “Bad Climate”:

One explanation for the high rates of sexual assault on college campus is that many students will perpetuate incidents of sexual assault if the opportunity arises. A number of factors contribute to a climate in which many students, and young men in particular, commit sexual assault. Some situational factors that promote high rates of participation in sexual assault are: young men’s alcohol consumption and fraternity culture, lack of awareness regarding when women are too intoxicated to consent, differences in status and power between men and women, and widespread demeaning attitudes about women. The fact that so many young men are involved in this phenomenon means that women on campus will have a hard time distinguishing who on campus is a potential assailant.

This was followed by an illustration (see Figure 1).

Endorsement of explanations for sexual assault

After participants read about each model, they were asked three questions (Cronbach’s α = 0.92 for each model) related to its endorsement: “To what extent you think this probably accounts for the high rates of sexual assault on college campuses?”, “To what extent do you think this is the right way of describing the phenomenon of sexual assault on college campuses?”, and “To what extent should colleges consider this view when they take action to reduce sexual assault on campus?” (1 = not at all to 9 = completely).Footnote 3

Results

Overall, support for the serial rapist model (M = 5.68, SD = 1.85) and the rape culture model (M = 5.55, SD = 1.98) were negatively correlated r(499) = −0.23, p < 0.001. Of the 455 participants (M = 4.47, SD = 2.28) who completed the question, 50 identified as extremely liberal for all three questions, 18 as extremely conservative for all three questions.

Predicting support for “Bad Apples”

We found that some of the predicted worldviews did indeed predict support for the serial rapist model of campus sexual assault. Specifically, we found that those who score higher on need for closure (B = 0.29, SE = 0.11, CI = [0.07, 0.51], p = 0.01), need for justice (B = 0.17, SE = 0.09, CI = [0.001, 0.34], p < 0.05) and in belief in essentialism (B = 0.30, SE = 0.08, CI = [0.14, 0.47], p < 0.001) were all more likely to endorse the serial rapist model. Contrary to our hypotheses, neither system justification motivation (p = 0.09) nor social dominance orientation (p = 0.64) were significantly associated with endorsement of the serial rapist model. When we exclude participants who failed the true/false comprehension question regarding the Bad Apples explanation, neither need for closure nor belief in a just world significantly predict endorsement of the serial rapist model. We conducted separate regressions because some worldviews were highly correlated, ranging from r(389) = −0.02 to r(385) = 0.75 (see Supplementary Appendix Table 1 for correlation matrix). In a model simultaneously regressing all measured worldviews, with and without demographic variables, on endorsement of the serial rapist model, only essentialism remains a significant predictor (Supplementary Appendix Tables 2 and 3).

The only demographic variables significantly associated with endorsement of the serial rapist model were income, which negatively predicts support for the serial rapist model, such that moving up one bracket in our four bracket income rating is associated with reduced endorsement of the serial rapist model by approximately 0.23 on the rating scale from 1 to 9, and conservatism, which was positively associated with endorsement. A one-point increase in our nine-point political ideology scale (i.e., self-rating as more conservative by one point) results in an increase of 0.10 in endorsement of the serial rapist model (see Supplementary Appendix Table 3, for the multivariate regression including all worldviews and demographics).

As hypothesized, we did not find a relationship between endorsement of the serial rapist offender model and the individualizing moral foundations (i.e., harm/care, equality; p > 0.05), which tend to relate to liberalism (Graham et al., Reference Graham, Haidt and Nosek2009). Also as hypothesized, we did not find a relationship between need to belong and support for the serial rapist model, p > 0.05. We were surprised to find that some of the scales we hypothesized would not relate to endorsement of the serial rapist model in fact did correlate significantly. Specifically, we found that increased belief in free will to positively predicted endorsement of the serial rapist model (B = 0.52, SE = 0.11, CI = [0.30, 0.74], p < 0.001), as did belief in the binding moral foundations (i.e., authority, loyalty and purity; B = 0.47, SE = 0.09, CI = [0.29, 0.65], p < 0.001), which tend to relate to conservatism (Graham et al., Reference Graham, Haidt and Nosek2009). (For the model simultaneously regressing all measured individual differences for discriminant validity with and without demographic variables on endorsement of the rape culture model, see Supplementary Appendix Tables 6 and 7.)

Predicting support for “Bad Climate”

As predicted, need for closure, system justification, and need for justice to do not predict support for the rape culture model (all p > 0.05). We did find however, that belief in essentialism was significantly associated with endorsement of the “Bad Climate” model (B = 0.21, SE = 0.09, CI = [0.03, 0.38], p < 0.05). We also found that social dominance orientation was negatively associated with endorsement of the “Bad Climate” model (B = −0.27, SE = 0.07, CI = [−0.24, −0.09], p < 0.001) though this relationship does not exist when we exclude those who failed the true/false comprehension question regarding the Bad Climate explanation. For the model simultaneously regressing all measured individual differences with and without demographic variables on endorsement of the Bad Climate model, see Supplementary Appendix Tables 6 and 7.Footnote 4

Discussion

In Study 1, we found some preliminary evidence for our primary hypothesis that endorsement of the serial rapist model of sexual assault perpetration is related to some worldviews and needs regarding a lack of ambiguity, a just and good status quo, and simple stories about people. Need for closure, essentialism and belief in a just world were significantly correlated with endorsement of the serial rapist model. Our tests of the discriminant validity of these individual worldviews suggest that the same worldviews correlated with the serial rapist model endorsement do not generally predict endorsement of an alternative (though not incompatible) model of sexual assault perpetration.

Study 2

To further investigate the preliminary results from Study 1, we replicated our survey with a larger and nationally representative sample in Study 2. For Study 2, we were only interested in replicating our primary hypothesized relationships between endorsement of the serial rapist modelFootnote 5 and need for closure, essentialism, belief in a just world, social dominance orientation and system justification. We removed all items from Study 1 regarding discriminant validity, including the description and questions about endorsement of the Bad Climate model, and individual differences that we did not expect to relate to endorsement of the serial rapist model. We added an additional questionnaire regarding gender system justification (Jost & Kay, Reference Jost and Kay2005) which measures how much people think that status quo gender norms are just. Unless otherwise noted, all materials were the same as Study 1. We report how we determined our sample size, all data exclusions (if any), all manipulations, and all measures in the study. We pre-registered all survey items, item groupings and analyses. All pre-registrations, materials, code and data available at the Open Science Framework (osf.io/guafe).

Methods

Participants and design

In the summer of 2017, we recruited 735 (368 males, 367 females) participants recruited through Qualtrics, which maintains a panel base proportioned to the general United States population. Participants ranged in age from 18 to 87 (M = 46.19, SD = 15.89). As part of Qualtrics’ quality control, participants were excluded if they did not correctly answer the true or false comprehension question regarding the serial rapist model of sexual assault perpetration.

Procedure

As in Study 1, participants completed the individual worldviews scales in a randomized order, then read the description of the serial rapist model, answered questions about their endorsement of it, and completed demographic questions.

Individual difference measures

We added the system justification-gender scale, of which a representative item reads: “In general, relationships between men and women are fair” (1 = strongly disagree to 9 = strongly agree). All scales obtained a Cronbach’s alpha above 0.66, except for system justification of gender (α = 0.49) and social dominance orientation (α = 0.58).

Results

Worldviews predicting endorsement of the serial rapist model

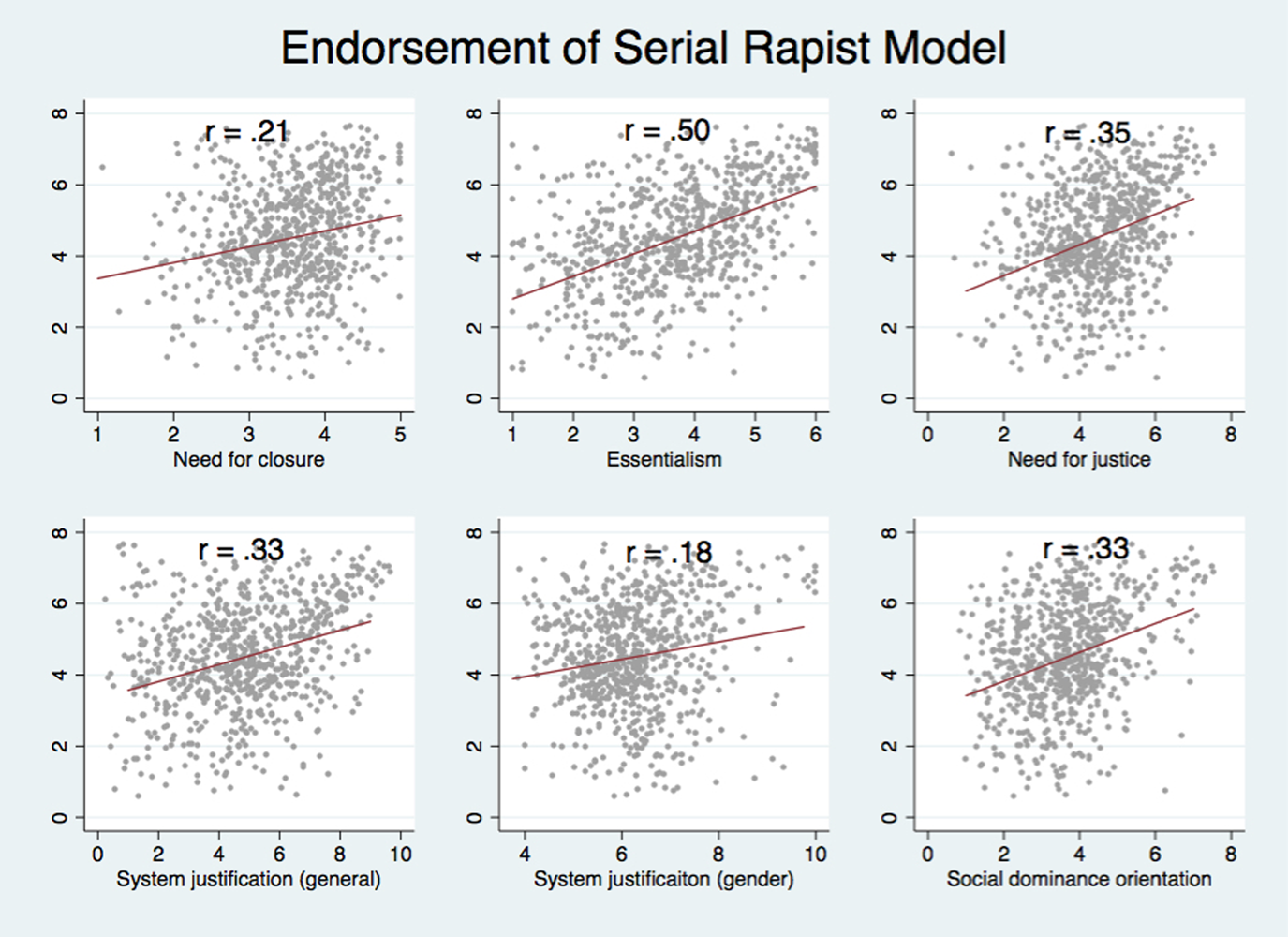

All of our measured individual differences in worldviews predicted support for the serial rapist model (see Figure 2). Specifically, need for closure (B = 0.59, SE = 0.12, 95% CI = [0.37, 0.82], p < 0.001), essentialism (B = 0.84, SE = 0.06, 95% CI = [0.73, 0.95], p < 0.001), need for justice (B = 0.58, SE = 0.06, CI = [0.45, 0.70], p < 0.001), social dominance orientation (B = 0.54, SE = 0.06, CI = [0.43, 0.65], p < 0.001), system justification motivation (B = 0.32, SE = 0.04, CI = [0.25, 0.40], p < 0.001) and system justification-gender (B = 0.33, SE = 0.07, CI = [0.18, 0.47], p < 0.001), predict endorsement of the serial rapist model. We conducted separate regressions because all worldviews were correlated, ranging from r(733) = 0.08 to r(733) = 0.60 (see Supplementary Appendix Table 8 for correlation matrix).

Figure 2. Greater need for closure, essentialism, need for justice, system justification and social dominance orientation all predict support for the serial rapist model.

In a simultaneous regression including all of these worldviews with demographic, SES, and ideological differences, need for closure and both system justification measures are no longer significant predictors of support, but essentialism, need for justice, and social dominance orientation remain significantly related (see Supplementary Appendix Table 9).

Demographics predicting endorsement of the serial rapist model

For political ideology (M = 5.19, SD = 2.16 for 1 = extremely liberal to 9 = extremely conservative), we had 32 participants select extremely liberal for all three questions, and 45 select extremely conservative for all three questions (Cronbach’s α = 0.93). Replicating our previous study’s results, a simultaneous regression using all demographic and SES data to predict endorsement of the serial rapist model indicates that higher conservatism predicts endorsement of the serial rapist model, B = 0.22, SE = 0.04, 95% CI = [0.14, 0.29], p < 0.001. We also find that men are more likely than women to endorse the serial rapist model, (B = 0.32, SE = 0.14, CI = [0.04, 0.59], p < 0.05). Controlling for whether participants were enrolled in college at the time, having more education is a significant negative predictor of endorsement of the serial rapist model, (B = −0.14, SE = 0.06, CI = [−0.25, −0.03], p < 0.05). However, being currently enrolled in college positively predicts endorsement of the serial rapist model, (B = 0.72, SE = 0.26, 95% CI = [0.21, 1.23], p < 0.01).

General Discussion

Across two studies, we find support for the idea that the serial rapist model appeals to individuals who hold worldviews endorsing a lack of ambiguity, a just and good status quo and simple stories about people. In both Studies 1 and 2, we find evidence that endorsement of the serial rapist model correlates positively, and in most cases significantly, with higher scores on scales that measure need for closure, essentialism, need for justice, system justification (both in general and with respect to gender issues) and social dominance orientation. In both studies, ideological conservatives were more likely to endorse the serial rapist model, but the worldviews that we measured still predicted serial rapist model endorsement significantly, over and above political orientation. While we see mixed results in Study 1, we replicated those findings as well as found evidence for all of our original hypotheses in Study 2 with a larger, representative sample.

The small differences between studies in support for our hypotheses, with Study 1 supporting our hypotheses to a lesser extent, could be due to unobserved differences between the non-representative Study 1 sample and the slightly larger nationally representative Study 2 sample. Differences could also be due to differing survey content: Study 2 did not mention the second account for sexual assault used in Study 1, the culture of rape or bad climate account. Future research could examine the effect of multiple vs singular narratives about the perpetration of sexual assault.

Why are these findings important? Psychological research reveals that if an explanation for the state of the world appeals to our basic need or fundamental worldview, we are more likely to believe in the explanation (Pratto et al., Reference Pratto, Sidanius, Stallworth and Malle1994) and to resist contradicting evidence (Kunda, Reference Kunda1990; Ditto et al., Reference Ditto, Scepansky, Munro, Apanovitch and Lockhart1998; Tetlock, Reference Tetlock2002; Taber & Lodge, Reference Taber and Lodge2006). Policy preferences based on a broader worldviews and preferences are also less likely to be changed by research evidence in the short run (Weiss, Reference Weiss1977). Endorsement of the serial rapist model may also influence which sexual assaults are more likely to be taken seriously by administrators, the legal system and by bystanders themselves.

Endorsement of the serial rapist model is undoubtedly influenced by more than individual worldviews, political ideology and gender. Situations and timely events should also influence endorsement. For example, news events like the revelation of the criminal behavior of Harvey Weinstein (Kantor & Twohey, Reference Kantor and Twohey2017), likely increase the accessibility and perceived validity of the serial rapist model (Tversky & Kahneman, Reference Tversky and Kahneman1974). There is no disputing the existence of serial rapists, but as we have reviewed in this paper, more recent and rigorous research (e.g., Swartout et al., Reference Swartout, Koss, White, Thompson, Abbey and Bellis2015) finds that we cannot attribute the majority of sexual assaults on college campuses to serial rapists.

While the present research examines why members of the general population might endorse the serial rapist model, subsequent research can extend these findings to account for why university administrators and policymakers favor bystander interventions, and explicitly or implicity use the serial rapist model to justify bystander interventions. As classic behavioral research demonstrates, even experts are subject to the same biases and mistaken judgments as laypeople (Tversky & Kahneman, Reference Tversky and Kahneman1974). Future research would also do well to extend our studies to individuals’ theories about the causes of workplace harassment and sexual assault more broadly, and to track individuals’ schemas regarding sexual assault and its causes over time.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/bpp.2022.28.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Jason Chin for help with data collection and manuscript preparation, and Kyonne Isaac for help with manuscript preparation. AG and ELP participated equally in all aspects. This work has been presented at the Women in Public Policy Seminar series at the Harvard Kennedy School. This research was supported by a grant from the Canadian Institute for Advanced Research (ELP).