LEARNING OBJECTIVES

-

Understand the various formats that journal clubs may take and reflect on how these relate to different aims

-

Understand the evidence base for the effectiveness of journal clubs in meeting their aims

-

Recognise the factors that are important in setting up or revitalising a journal club and consider strategies to overcome potential barriers

‘Job plans must include dedicated time for academic and educational activities such as attending journal clubs’, declare the eligibility criteria for Royal College of Psychiatrists’ examinations (Royal College of Psychiatrists 2015: p. 3). Journal clubs are also mentioned as an important aspect of continuing professional development (CPD) for UK consultant and staff grade and associate specialist (SAS) psychiatrists in College guidelines. Since the critical review paper was introduced into the MRCPsych examinations in 1999, journal clubs have been seen as one of the main opportunities to teach critical appraisal in psychiatry. However, Glasziou's complaint that ‘Many journal clubs are boring because the articles are quickly trashed as poor research and nothing changes’ (Reference GlasziouGlasziou 2007) is not uncommon. Are journal clubs useful tools in teaching?

What are the aims of psychiatric journal clubs?

Keeping up with the literature

The literature on psychiatric journal clubs is sparse and most evidence has to be extrapolated from other branches of medicine or social sciences and from research into educational theory. Traditionally, journal clubs have been viewed as a way of supporting clinicians and trainees in keeping up with current literature and research. In the 19th century Sir James Paget described ‘a small room over a baker shop near the Hospital-gate where we could sit and read the journals and where some, in the evening, played cards’ (Reference LinzerLinzer 1987). Over the next 100 years journal clubs became a regular part of higher and continuing medical education across all specialties, including psychiatry, where almost all training programmes in the UK and USA now have regular journal club meetings to discuss recent papers (Reference Strauss, Yager and OfferStrauss 1980; Reference Taylor and WarnerTaylor 2000).

With the development of online publishing, accessing research online has in some ways become much easier, but the sheer quantity of published material makes it difficult to pick out the needles of high-quality papers in the haystack of offerings on Athens. No one can possibly absorb all the papers published: we need new methods to find research that is valid and applicable.

Acquiring skills in evidence-based medicine

To provide such an approach, researchers at McMaster University in the USA proposed the concepts of evidence-based medicine (EBM) as a way of ‘systematically finding, appraising and using contemporaneous research’ (Reference Rosenberg and DonaldRosenberg 1995). These can be summarised in four steps (Reference GilbodyGilbody 1996), expanded on in Box 1:

-

1 formulate the question

-

2 search the literature

-

3 evaluate the evidence

-

4 implement the findings.

BOX 1 Gilbody's four steps of evidence-based medicine

-

1 Formulate a clear clinical question regarding patient care

-

2 Search the literature for relevant clinical studies

-

3 Evaluate (‘critically appraise’) evidence for effectiveness and usefulness

-

4 Implement useful findings in clinical practice

EBM became seen as the best way of ensuring that a clinician's opinion, potentially limited by knowledge gaps or biases, is supported by evidence from the scientific literature so that best practice can be determined in the context of the patient's views and values. As EBM evolved, journal clubs aspired to the more specific goal of helping clinicians, and in particular trainees, to acquire the skills necessary to adopt this approach. EBM clubs covering all four steps outlined by Gilbody and integrated with clinical work may be seen as the gold standard of journal clubs. In an EBM journal club, the presenter describes a clinical scenario, formulates a question emerging from it, demonstrates the search strategy to find relevant, reliable research, appraises a relevant paper and considers how applicable it is to their initial scenario.

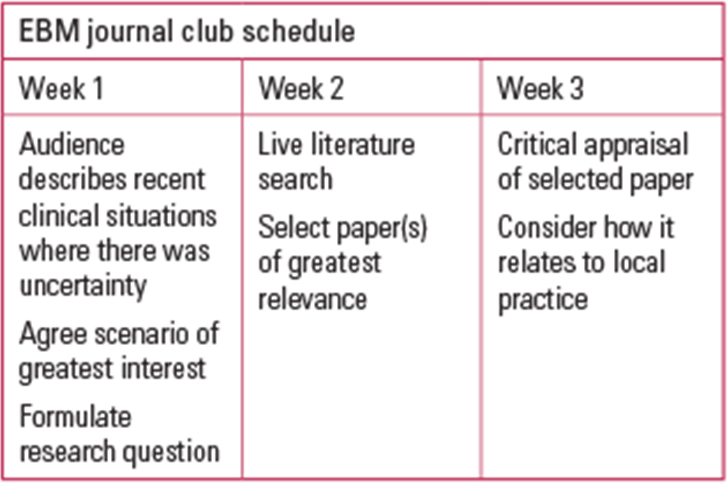

Journal clubs traditionally last 1 hour, but covering all the steps set out by Gilbody is difficult in this brief time. Some EBM clubs are therefore run in cycles over 2–4 weeks, with different combinations of question generation, search, appraisal and presentation of a critically appraised topic. For example, in a 2-week cycle the first meeting might involve 45 minutes spent critically appraising a paper, followed by 15 minutes focusing on formulating a specific question that emerges from a clinical scenario. The new presenter then takes the question, searches the literature (with support from a facilitator) and brings back a paper to appraise the following week.

Reference Phillips and GlasziouPhillips & Glasziou (2004) have suggested that the weakest aspect of most clubs is the part focused on searching the literature, so it may be useful to have longer cycles of 3 or 4 weeks, where the literature search is conducted live during one session (Fig. 1). The challenge with running a journal club over several weeks is that the audience may vary depending on leave, rest periods and so on, which can make it difficult to maintain momentum.

FIG 1 An EBM journal club run over a 3-week cycle.

Passing the critical review component of the MRCPsych

Running an EBM journal club relies on having facilitators with appropriate skills to formulate questions and teach search strategies (Box 2). Jobbing clinicians do not always feel confident in these areas (Reference Warner and KingWarner 1997), particularly if they are required to demonstrate these skills in front of an audience of peers and trainees.

BOX 2 Resources to support facilitators of EBM journal clubs

-

Seek to engage academic psychiatrists and other professionals in the journal club: consider clinical psychologists, NHS trust librarians, local statisticians

-

Consider attending a course in EBM or the teaching of EBM: the Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine in Oxford offers recommended training (www.cebm.net)

-

Review the syllabus for the MRCPsych Paper 3 critical review, which includes basic biostatistics and is still current for the new paper B (Royal College of Psychiatrists 2011)

Virtual clubs

-

Cochrane Journal Club (www.cochranejournalclub.com)

-

PubMed Commons Journal Clubs (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmedcommons/journal-clubs/about)

Useful books

-

The Doctor's Guide to Critical Appraisal (4th edn, 2015) by Narinder Gosall & Gopal Gosall: the authors run the Superego Café Revision courses and the publisher is PasTest

-

Critical Reviews in Psychiatry (3rd edn) (2005) by Tom M. Brown & Greg Wilkinson. This was published by the Royal College of Psychiatrists under the Gaskell imprint (now RCPsych Publications)

Moreover, assessing the ability to formulate questions and conduct literature searches does not lend itself easily to a formal examination process. From the spring of 1999, the Membership examination of the Royal College of Psychiatrists (the MRCPsych) has included a critical review paper, the aspiration being that trainees studying for this paper would subsequently have a greater commitment to EBM throughout their career. A new paper, MRCPsych Paper B, was launched in April 2015, replacing the old Papers 2 and 3, and the critical review component makes up one-third of Paper B. The syllabus for the critical review topic (Royal College of Psychiatrists 2011) has not changed: theoretically, it covers all four steps of EBM, but in practice the emphasis in the exam tends to be on critical appraisal.

A key aim for many psychiatric journal clubs has become to support psychiatric trainees in passing the critical review component of their exams. Although a national survey (Reference Taylor, Reeves and EwingsTaylor 2004) suggested that most clubs are run on evidence-based lines, respondents were specifically asked whether their trainees received teaching in formulating questions and searching the literature. Receiving teaching is not the same thing as putting these skills regularly into practice. It would be an interesting research project to explore the extent to which journal clubs in psychiatry cover the whole range of EBM. My impression is that such clubs are rare, both because of the practical difficulties described above, and because of a lack of confidence among facilitators. In contrast, clubs that focus on the critical appraisal of a specific study are relatively easy to run: there is an agreed process and trainees are often encouraged to work their way systematically through a series of questions (known as critical appraisal tools) such as those suggested by the JAMA users’ guide to the medical literature (Reference Guyatt and RennieGuyatt 1993), the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP: www.caspuk.net) or the Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine (CEBM: www.cebm.net/critical-appraisal). The risk with these tools is that it is possible to take a ‘painting-by-numbers’ approach, commenting on study design, bias and so on without feeling confident to give an overall judgement on the quality of the paper and its applicability to clinical practice.

An alternative approach and one that often provokes lively debate is the reverse critical appraisal journal club, where a clinical question is posed and the audience is asked to design a study that would best answer it (Reference Stallings, Borja-Hart and FassStallings 2011). The ensuing discussion then informs the subsequent critical appraisal of the chosen article. This approach helps the audience recognise the challenges faced by the researchers: however, it is more demanding of the facilitator's abilities in critical appraisal.

Learning theory (Box 3) reminds us that the majority of students will focus their learning on the demands of the examinations facing them. Perhaps it is not surprising that the other steps in EBM, namely formulating questions from clinical scenarios, undertaking literature searches and thinking about application to clinical practice, have been relatively ignored in many psychiatric journal clubs as, although these steps mirror best clinical practice, they are not formally examined in the same way as critical appraisal.

BOX 3 Adult learners

According to learning theory, adult learners:

-

want to be clear that they need to know something before engaging with it

-

prefer self-directed learning

-

want their reservoir of experience to be acknowledged

-

prefer a task-centred approach to learning

-

are more motivated if learning tasks are similar to real-life situations

Another difficulty with having examination success as a primary aim for a psychiatric journal club is that it may not engage potential audience members. Adult learning theory stresses the importance of real-life scenarios, establishing a need to know and a task-centred approach. Senior clinicians are likely to be less interested in attending journal clubs if the format does not relate to the dilemmas they encounter in routine practice, and educational meetings where senior staff are absent tend to be less positively rated by trainees (Reference Heilligman and WollitzerHeilligman 1987). Many trainees based in psychiatry are in their foundation years or are working in psychiatry as part of general practice training: education targeting a specific psychiatric exam may appear less relevant to them too, although critical appraisal is a formal part of general practitioner (GP) training.

Other aims: professional development and bonding

Critical appraisal clubs focus on assessing the validity of specific studies. Other formats may emphasise different components of EBM more relevant to particular audiences.

Reference Cave and ClandinnCave & Clandinn (2007) described a journal club that focused on books rather than research papers. The books chosen were written by physicians, ‘stories of their lives, the lives of their patients and the clinical problems with which they live’. They give the example of a discussion on The Anatomy of Hope by Jerome Reference GroopmanGroopman (2005). Groopman, Professor of Medicine at Harvard, writes of his personal and professional struggle to balance the needs of nurturing hope with those of being truthful and realistic in discussing prognosis with patients and friends facing serious illness. This journal club was attended by doctors from trainees to highly experienced consultants and it aimed to foster links between participants and help doctors develop different ways of understanding relationships between colleagues and between doctors and patients. Discussing such works may seem unusual in the context of a journal club, but the authors quote Reference SackettSackett (1997) as including in his principles of EBM, ‘individual clinical expertise that incorporates “thoughtful identification and compassionate use of individual patients’ predicaments, rights and preferences in making clinical decisions”’. Such a journal club format can therefore be considered to relate to the fourth step of EBM, namely how to understand and apply the research evidence in the context of the individual patient.

Cave & Clandinn were interested in helping doctors deepen their relationship with medical colleagues at different stages in their careers. Other authors have focused on increasing cohesion and mutual support in other professional groups or in multidisciplinary teams (Reference Dobrzanska and CromackDobrzanska 2005; Reference Mukherjee, Owen and HollinsMukherjee 2006; Reference Bilodeau, Pepin and St-LouisBilodeau 2012). There is increasing awareness of the importance of a strong bond between colleagues in contributing to a culture of compassion and intelligent kindness in healthcare (Mid Staffordshire NHS Foundation Trust Public Inquiry 2013). Community-based specialties such as psychiatry face a particular challenge in fostering camaraderie in a workforce that is geographically dispersed, and there are interesting parallels with groups such as school nurses, where an online journal club presentation and moderated discussion gave participants a sense of connecting with each other and decreased isolation (Reference SortedahlSortedahl 2012).

In the nursing literature, Reference Campbell-Fleming, Catania and CourtneyCampbell-Fleming et al (2009) suggest that busy in-patient and community nurses are less interested in ‘the luxury to critique literature’. In their US study, the facilitator's role thus became to select high-quality, relevant studies where the results could be accepted and the discussion could concentrate on the applicability of the findings to their daily work. The same lesson emerged from Reference Dobrzanska and CromackDobrzanska & Cromack's UK study (2005) where the nurses likened an academic focus on critical appraisal to ‘a college lecture’. The club was more successful when the emphasis was on a presentation of a clinical topic based on high-quality studies identified by a research facilitator. Dobrzanska & Cromack remind us that: ‘the reality of enhancing critical appraisal skills among staff who may not have studied for a considerable length of time is difficult to achieve’.

Where participants bring differing levels of expertise and skills in critical appraisal, clubs need to find ways of ensuring that the format allows all present to engage. One option suggested by Reference Mukherjee, Owen and HollinsMukherjee et al (2006) in a group including doctors, psychologists, and clinical and social science researchers is to alternate qualitative and quantitative papers. Some professional groups, such as clinical psychologists and social science researchers, often have greater expertise in assessing qualitative papers, in contrast to the experience of doctors and clinical researchers in quantitative approaches, so this facilitates learning from each other.

Thus, journal clubs need to have clear, agreed aims that meet the needs of their target audience. The next step is that they should meet regularly and consistently – what helps them do this?

Effectiveness of journal clubs

Longevity and attendance

Early studies of journal clubs’ effectiveness considered the factors associated with high attendance rates and ‘the avoidance of periodic abandonment’ (Reference SidorovSidorov 1995; Reference AlguireAlguire 1998; Reference Deenadaylalan, Grimmer-Somers and PriorDeenadayalan 2008). Smaller teaching programmes, having one person taking responsibility for the club and providing continuity as facilitator, discussing original research and providing food were all seen as important. The consistent and enthusiastic participation of senior staff was particularly commented on in psychiatry training programmes, with trainees appreciating the opportunity to meet more experienced colleagues with clinical and research backgrounds (Yager 1991).

Attendance in the 21st century – virtual journal clubs

Over the past decade changes in workplace practices make earlier literature on journal club attendance more difficult to apply to current situations. Within medicine, the European Working Time Directive and other developments have limited the total number of hours that can be worked and made rest periods obligatory. In most specialties, including psychiatry, this has meant a move from an on-call system to a shift system. ‘Mandatory’ attendance is thus harder to implement as trainees are required to rest before and after each shift: the combined effect of the numbers on the rota, compulsory rest days and annual leave means that many trainees are not available to attend teaching sessions. Furthermore, there has been a perceived increase in the intensity of the workloads of psychiatry trainees and consultants (Reference HarrisonHarrison 2007) that makes it harder for both to carve out time to attend teaching sessions, especially as these can be at a considerable distance from the work base. Finally, the change in attitude towards drug company sponsorship has meant that providing food at any meeting is less common than it was. Linked to these challenges, there has been increased interest in virtual journal clubs, both synchronous and asynchronous.

Synchronous clubs

Synchronous clubs are where the participants are in separate locations, but take part in the journal club at the same time, like the club for school nurses previously mentioned (Reference SortedahlSortedahl 2012). This club used a web-conferencing program so participants were emailed material a week before sessions; at a preset time they logged into a PowerPoint session where they could hear the presenter. They could type questions and comments during the presentation and then they participated in a moderated online discussion. Currently, the company Blackboard is probably the biggest provider globally of such educational web-conferencing programs. Other synchronous journal clubs have used video-conferencing, teleconferencing or even avatars in virtual worlds such as Second Life (Reference BakerBaker 2013)!

Asynchronous clubs

In asynchronous clubs, the participants have a period of time, usually a few days to a few weeks, to participate. In a co-authored article, Thangasamy has described how he and two urology colleagues were in the habit of sharing online discussions on published research papers (Reference Thangasamy, Leveridge and DaviesThangasamy 2014). They decided to set up together the International Urology Journal club via Twitter. The club was mainly advertised by word of mouth and participation was encouraged by awarding a prize for the best tweet each month. The lead author of the chosen paper was invited to participate in the discussion. The format proved successful in attracting new followers and so some journals decided to allow journal club members free access to papers chosen for discussion. Thangasamy et al comment that this format not only supports participants in staying abreast of current literature, but also plays a social role, in that the conversations between participants, and particularly those involving the papers’ authors, often lead to developing conversations and connections that persist long after the formal discussion is closed.

Other asynchronous journal clubs have used social media platforms such as LinkedIn and Facebook as well as emails, blogs and wikis (websites or databases developed collaboratively by a community of users, allowing any user to add and edit content).

Journals and online organisations have been quick to get involved in such online clubs. The British Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology has developed formal links with a Twitter-based journal club (Reference Leung, Tirlapur and SiassakosLeung 2013). Authors submitting studies to the journal are invited to prepare slides and a discussion guide for their paper, which can then be used in a traditional face-to-face journal club but are also posted online. Over the subsequent week each comment posted on Twitter with the relevant hashtag is summarised and published. A journal club host moderates the discussion and provides the edited summary for publication.

The Cochrane Library now offers a monthly journal club where the lead author of a recent Cochrane review explains the key points in a podcast and there are downloadable PowerPoint slides and discussion questions. This material can be used at a traditional journal club, but can also be accessed by individuals in their own time and users are encouraged to pose questions to the authors. A recent Cochrane journal club focused on a review of training to recognise the early signs of recurrence of schizophrenia (Vinjamuri undated). Similarly PubMed recently created ‘PubMed Commons Journal Clubs’ (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmedcommons/journal-clubs/about). Here, individual journal clubs post the key points, questions and summaries from their discussions, and a PubMed Commons member who is also a member of the journal club acts as guarantor. Although there are not as yet any mainstream psychiatry journal clubs linked with this initiative, there are health psychology and psycho-oncology clubs. The posts and any subsequent comments are linked on PubMed to the original paper.

As with all technological advances, fast adapters are quick to sing their praises (Reference BakerBaker 2013). Conversely, other groups have described difficulty in maintaining participation in virtual groups. When initial enthusiasm for their internal medicine virtual journal club faded after 3 months, Reference Kawar, Garcia-Sayan and Baker-GenawKawar and colleagues (2012) needed to reinvigorate their approach by reinstating face-to-face meetings in the trainees’ timetables. They found participation was best when trainees met as a group and reviewed articles with teaching staff and then posted comments online. They also encouraged the participation of teaching staff by arranging for them to gain credits by participating via the blog. Reference McLeod, MacRae and McKenzieMcLeod and colleagues (2010) also found that it was harder to promote good participation in a virtual general surgery journal club compared with a face-to-face group. It seems that the social aspect of face-to-face meetings may be an important component of a club's success unless participants are particularly well motivated.

Knowledge, skills, attitudes and behaviour in EBM

In assessing the effectiveness of journal clubs, the main outcomes that have been considered relate to: skills and knowledge of critical appraisal specifically or EBM more generally; impact on clinicians’ behaviour; effect on the care offered to patients; and impact on patient outcomes. There is an overlap between the literature on the effectiveness of journal clubs and that on the effectiveness of teaching critical appraisal, where other approaches, such as stand-alone workshops, may be considered in addition to regular journal clubs.

Systematic reviews of critical appraisal teaching point to a reasonably consistent picture (Reference Ebbert, Montori and SchultzEbbert 2001; Reference Coomarasamy and KhanCoomarasamy 2004; Reference Honey and BakerHoney 2011; Reference Horsley, Hyde and SantessoHorsley 2011). The number of high-quality studies is limited, but it seems likely that teaching critical appraisal is associated with a small but demonstrable improvement in critical appraisal knowledge and skills. It is not clear that there is any change in attitudes (for example, about the need to conduct literature searches) or in behaviour. There are no convincing studies looking at the impact of teaching critical appraisal on patient outcomes.

In a systematic review of 23 studies involving post-graduate medical trainees, Reference Coomarasamy and KhanCoomarasamy & Khan (2004) distinguished between standalone teaching and integrated methods. With integrated teaching, the training was either in real time, for example as part of ward rounds when clinical dilemmas presented themselves, or in formal teaching sessions, but based on specific encounters with patients on the wards and in clinics. They found important differences between the two approaches. Both methods seemed to be associated with improvements in knowledge, but only integrated methods led to clear-cut improvements in the application of this knowledge, the willingness to use it (change in attitudes) and a subsequent change in behaviour. Similarly, in the nursing literature, a recent systematic review did not find any evidence that journal clubs have an impact on the implementation of evidence-based nursing (Reference Häggman-Laitila, Mattila and MelenderHäggman-Laitila 2016).

Regular journal clubs may have an advantage over other methods of teaching critical appraisal in that there is an opportunity to regularly reinforce learning. However, there is no evidence to date to substantiate an effect of journal clubs on attitudes and behaviour, or on the delivery of care and patient outcomes.

Setting up or revitalising a journal club

Journal clubs are very common in psychiatry training schemes and are seen as the mainstay of delivering evidence-based psychiatry. They are expensive in terms of the costs of the participants’ time. They are not consistently experienced as productive learning experiences and there is an absence of evidence to demonstrate an effect on participants’ behaviour or on patient outcomes.

Given this, Reference Horsley, Hyde and SantessoHorsley et al's (2011) call for a high-quality, multi-centre, randomised controlled trial on the teaching of critical appraisal must be a priority and should include consideration specifically of the role of journal clubs.

Studying the effect of journal clubs on patient outcomes will be difficult and lengthy. In the meantime, tutors and others responsible for organising and delivering journal clubs need to take heart from the evidence that these clubs do improve knowledge and skills in critical appraisal. They also need to consider how all aspects of evidence-based psychiatry can be supported, including the integration of clinical expertise and understanding of the patient's wishes and needs in the context of the best available research evidence.

When setting up or revitalising a psychiatry journal club (Box 4), consider carefully the aims and intended audience. It is likely that a club primarily focused on supporting psychiatry trainees to pass a critical review paper will struggle to attract a broader audience.

BOX 4 Key factors for journal club success

-

Regular and anticipated meetings

-

Clear long- and short-term aims

-

A trained facilitator taking responsibility for the club and providing continuity

-

Enthusiastic participation by senior staff

-

Including a social component to the club

-

Integrating best research evidence with clinical expertise and an understanding of patients’ wishes and needs

Second, consider the social role. Clubs that address social needs of participants are more likely to be well attended and persist for longer. Skilled facilitators who provide continuity are an important component in a successful club. Trainees value opportunities to meet with more experienced colleagues, so the club also needs to attract other senior staff. Help with search strategies should be sought from a librarian wherever possible.

It is worth exploring the possibility of meeting for a longer session or running the club over cycles of several weeks, so that formulating a question from a clinical dilemma, searching the literature, appraising the chosen paper and thinking about its applicability can all be given time.

What positive reinforcements could be considered for trainees and senior staff? Published letters to editors (Reference Edwards, White and GrayEdwards 2001) or comments and discussions posted online may increase enthusiasm and be seen as a useful addition to a trainee's portfolio. Many psychiatrists would like to feel more confident in their use of evidence-based psychiatry. Educational supervisors are required to participate in educational CPD: sharing information about EBM courses may encourage colleagues to sharpen their skills in this area and thereafter become more enthusiastic participants in local journal clubs.

The evidence suggests that clubs that are closely integrated with clinical work may be more likely to change behaviour. At a simple level, journal clubs can be more formally linked to case presentations, with a dilemma described in the case presentation serving as a springboard for a subsequent journal club (Reference Warner and KingWarner 1997). Alternatively, encouraging consultants to prompt trainees to identify clinical dilemmas in clinics or on ward rounds, with these dilemmas then acting as the basis for the journal club, should improve the likelihood of integrating theory and practice and thus meet the ideals proposed by Reference Sackett and ParkesSackett & Parkes (1998) of providing the best possible care to patients.

MCQs

Select the single best option for each question stem

-

1 Factors demonstrably associated with good attendance at journal clubs include:

-

a offering asynchronous online clubs so they can be accessed over a specific period of time

-

b offering food

-

c linking journal clubs with case presentations

-

d organising clubs with video or teleconferencing

-

e drug company sponsorship.

-

-

2 The evidence regarding the effectiveness of journal clubs suggests that:

-

a stand-alone teaching sessions are not associated with improvements in knowledge of critical appraisal and evidence-based medicine (EBM)

-

b EBM cannot be satisfactorily integrated with real-life clinical dilemmas in a classroom setting

-

c teaching EBM in a way that integrates the theory with real-life clinical dilemmas is associated with improvements in patient-rated outcomes

-

d teaching EBM in a way that integrates the theory with real-life clinical dilemmas is associated with improvements in critical appraisal skills, i.e. the ability to apply knowledge to a given problem

-

e stand-alone teaching of EBM is associated with improvement in behaviour, for example routinely searching the literature to guide clinical practice.

-

-

3 In running a journal club:

-

a discussing qualitative papers is irrelevant to EBM

-

b sharing the task of taking responsibility for the journal club among a group of people is associated with longevity of the club

-

c clinical expertise is more important than training in EBM for the facilitator of the club

-

d prioritising the social aspect of the club is seen as unnecessary by trainees

-

e critical appraisal is a formal part of the GP curriculum.

-

-

4 Psychiatrists sitting the Royal College of Psychiatrists’ Membership examinations (MRCPsych):

-

a are required to have basic training in biostatistics

-

b are required to have time to attend journal clubs in their timetable

-

c can earn 10% of the overall marks for MRCPsych Paper B from critical review questions

-

d options a and b.

-

e all of the above.

-

-

5 In terms of different formats for journal clubs:

-

a reverse journal clubs start with the results and ask participants to work out the initial hypothesis

-

b nursing journal clubs often prefer to focus on original research

-

c clinical psychologists often have expertise in qualitative research

-

d attending workshops and conferences offers the best environment to learn evidence-based psychiatry

-

e face-to-face contact is associated with poorer participation rates generally than virtual journal clubs.

-

MCQ answers

| 1 | b | 2 | d | 3 | e | 4 | d | 5 | c |

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.