LEARNING OBJECTIVES

After reading this article you will be able to:

• appreciate the complexities associated with treatment of BPSD

• understand the importance of non-pharmacological approaches in the management of BPSD

• demonstrate familiarity with structured approaches, including the stepped-care model, to manage BPSD.

National guidelines, including those in the UK, support the use of non-pharmacological approaches as first-line treatments for the behavioural and psychological symptoms of dementia (BPSD) unless there are immediate risks requiring tranquillisation or sedation (Alzheimer's Society Reference Tible, Riese and Savaskan2017). Comprehensive reviews of the psychotropic treatment of BPSD using antipsychotics, benzodiazepines, antidementia drugs, hypnotics and mood stabilisers acknowledge the complex trade-offs between the costs and benefits of prescribing in this area (International Psychogeriatric Association Reference Howarth, Crooks, Sells, James and Jackman2015). The NICE 2018 guidelines suggest that before starting antipsychotics the benefits and harms of these drugs are discussed with the person, their family members or carers owing to their potential side-effects. Of particular concern is the problematic side-effect profiles of many of the drugs, in light of only moderate treatment efficacy (Tible Reference Smith, Hadaway and Reichelt2016). The situation is made even more difficult because of the multimorbidity, reduced drug metabolism and polypharmacy issues related to prescribing for this vulnerable group of patients. Owing to the complexities and problems associated with pharmacological management, National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidelines suggest that clinicians ‘offer psychosocial and environmental interventions to reduce distress’ (National Institute for Health and Care Excellence Reference Moniz-Cook, Swift and James2012, p. 25). However, this rather vague description of the nature of the non-pharmacological strategies offers no clear alternative to pharmacological solutions, thus resulting in a continued overreliance on medication.

It is estimated that 90% of people with dementia experience BPSD as part of their illness and over 70% of those with dementia living in care are displaying stress and distress at any one time (Lyketsos Reference Lyketsos, Carrillo and Ryan2011). BPSD are associated with worsening cognition and higher levels of caregiver burden; they increase the risk of acute hospital admissions and institutionalisation in residential and nursing care settings (International Psychogeriatric Association Reference Howarth, Crooks, Sells, James and Jackman2015; Feast Reference Duffy2016; Moniz-Cook Reference Moniz-Cook, Woods and Gardiner2017).

BPSD can be complex phenomena and to manage them appropriately a lot of information is potentially required, including details about the person's physical and mental health, premorbid personality, dementia type, medication regimen and environment. Two key features, or deficits, that often make treatment regimens for agitation different in dementia compared with many other presentations are: (a) short-term memory loss and (b) loss of insight into having deficits. In terms of the first feature, a reduction in short-term memory reduces the person's ability to engage in standard therapies because new learning is prevented; as short-term memory gets worse the person can potentially be unaware of time, place and orientation. They will become decoupled from the present reality and become time-shifted, occupying their own reality (e.g. believing their partner is still alive or that they have young children). If such deficits are accompanied by a loss of insight, the person will not be aware that their thinking is faulty and will thus be less inclined to be persuaded that their perspective may be wrong. When both of these deficits are present, the focus for non-pharmacological treatments often shifts to the carers and away from the person with dementia. It is the carers who are required to adjust their communication style and interactions to reduce the likelihood of triggering the BPSD. In other words, the caregivers become the ‘agents of change’.

Current models of care

One of the ways clinicians have attempted to help caregivers determine what they are required to do and say is by providing them with simple conceptual models or formulations.

The unmet-needs framework

A popular model is the ‘unmet-needs’ conceptualisation. Authors such as Algase et al (Reference Algase, Beck and Kolanowski1996) and Cohen-Mansfield (Reference Brechin, Murphy and James2013) have proposed that BPSD are an expression of distress that arises from physical or psychological unmet needs. For example, Cohen-Mansfield (Reference Brechin, Murphy and James2013) argues that BPSD often reflect an attempt by a person to signal a need that is currently not being met (e.g. to indicate hunger or to gain relief from pain or boredom), an effort by an individual to get their needs met directly (e.g. to leave a building when they believe they must go to work or to collect their children from school) or a sign of frustration (e.g. feeling angry at being told they are not allowed to exit a building). In all these situations, the actions are attempts by the individual to enhance and maintain their sense of well-being or to ease their distress. It is suggested that finding and resolving the unmet needs should be the focus of treatment.

Use of formulations

Formulations are crucial for identifying and exploring unmet needs and are utilised regularly by clinicians. However, there is a lack of a universally agreed definition of formulation, with different professionals bringing their own perspectives. Holle et al (Reference Dunn and Moniz-Cook2016) undertook a systematic review, identifying 14 frameworks currently in use for BPSD. They suggested that formulations play an important role in the treatment of BPSD, but they failed to identify a particular framework as being significantly superior to others. The importance of formulations is a view further supported by a Cochrane review that examined the use of functional analytic approaches in the area (Moniz-Cook Reference McCabe, Bird and Davison2015).

Despite support for their use, because formulations can be time-consuming and require training to be delivered effectively, they are not universally employed for all occurrences of BPSD. Indeed, it is important to recognise that there are circumstances where formulations are not required. Consider the following.

(a) Not all behaviours are ‘challenging’. We want people to be active and maintain interesting lives, in which they enjoy and explore their surroundings. Such activity is likely to lead people who have dementia to transgress some rules or norms within the setting in which they are residing but this does not necessarily make those actions ‘challenging’ and therefore they should not be pathologised.

(b) Some BPSD have a specific physical cause, which may be quickly treated via medication or physiotherapy. For example, dementias are associated with old age, as are other illnesses – such as delirium and pain – that can be common triggers for BPSD. Therefore, a simple physical screening can readily identify treatable causes of BPSD without the need for a formulation.

(c) A range of BPSD are predictable and carers can target ‘hot spots’ of distress without the need for an extensive functional analysis. For example, many confrontations are triggered when people with dementia are receiving intimate care, and therefore BPSD can be reduced if caregivers’ skills in the provision of intimate care are improved.

The stepped-care model

Brechin and colleagues used the above notions when they produced a four-stepped intervention programme for BPSD (Brechin 2013). The stepped-care model (Fig. 1) suggests that formulations are important, but because they are either not always required and/or are demanding in terms of time, resources and skills, three less-intensive steps should be used first.

FIG 1 Stepped-care management of behavioural and psychological symptoms of dementia. BtC, behaviour that challenges; CPN, community psychiatric nurse; GP, general practitioner.

Step 1 is recognition and screening: Many behavioural difficulties wax and wane and can be dealt with by caregivers through the sensitive use of good communication skills. In situations where the behaviour is not risky for either the person concerned or the caregivers, it may be appropriate for the circumstances to be tolerated for a while and many of the behaviours may resolve of their own accord (Alzheimer's Society Reference Tible, Riese and Savaskan2017). In addition, checks for conditions that might be causing agitation should be undertaken. Commonly one would assess for: infections, delirium, depression, side-effects of medication and pain or discomfort (arthritis, pain, including dental pain, etc.). The screening of such conditions is usually undertaken by medical staff, including general practitioners (GPs).

Step 2 involves low-intensity interventions: these are approaches used by non-specialist clinicians and caregivers outside of the National Health Service to identify behavioural patterns, emotions and the basic needs of people with dementia. Interventions might include: providing opportunities for fun and occupation to relieve boredom; altering the environment to ensure privacy or reduce overcrowding or noise levels; and obtaining more information about people's personal histories in order to communicate and interact with them better.

Step 3 uses high-intensity (protocol-led) interventions: in this step, assistance is provided by professionals such as nurses and occupational therapists who are trained to work with older people, with input from psychologists and psychiatrists in order to tailor interventions to individual presentations or needs. Generic protocols are used and often involve the use of monitoring charts (diaries or checklists) and behaviour checklists (McCabe Reference Kales, Gitlin and Lyketsos2015). Caregivers are supported by experienced, well-trained therapists in the use of behavioural techniques and more sophisticated forms of de-escalation.

Step 4 introduces specialist interventions (formulation-led approaches): in many situations steps 1–3 will be sufficient to treat BPSD. However, when it is difficult to determine the need and/or employ appropriate protocols, a more bespoke approach is required. This involves clinicians collecting additional information about the person and their circumstances. It is at this point Brechin et al recommend the use of a biopsychosocial formulation, involving a comprehensive assessment, integration of information, the development of a conceptualisation and a formulation-led care plan, and support for implementation (Brechin 2013).

Although Brechin et al's work produced a comprehensive treatment approach, it is potentially flawed in its clinical application, in that it does not explain how to appropriately use the knowledge gained from the assessments and formulations to bring about changes in behaviour, thus limiting its efficacy. A more fine-grained ‘how to’ set of guidelines is required.

The DICE approach

An equally extensive BPSD management programme has been provided by Kales et al (Reference James, Medea and Reichelt2015) in their DICE framework. Unlike the previous methodology, DICE does not contain steps, but the approach is applied whenever a behaviour is perceived as being ‘sufficiently’ challenging. DICE was developed in 2014 by a group of experienced psychiatrists and other clinicians in the USA. They ran a series of consensus meetings to devise a protocol to produce a treatment template for BPSD, the product of which was the DICE framework (describe, investigate, create, evaluate). The model suggests that there are three areas to assess and treat under each of the DICE headings: the person, the carer and the environment. This approach was specifically developed for people with dementia living in their own homes rather than in care settings.

In the first stage (describe), a thorough description of the BPSD and the context in which they occur is required. This is achieved through discussion with the person and the caregiver. The second stage (investigate) involves the clinician identifying and excluding any underlying causes (e.g. undiagnosed medical conditions or infections) and investigating any caregiver or environmental factors (e.g. noisy environment, the caregiver's communication style). The information gathered at this stage is then utilised in the third stage (create), whereby the person, caregiver and clinician work collaboratively to create and implement a treatment plan. The final stage is to evaluate the treatment strategies employed in stage 3, focusing on their efficacy for the BPSD and assessing how well the carers implemented them.

DICE is a helpful example of a treatment approach combining clear structural and process elements within a systemic conceptualisation. Some clinicians may suggest that the roles of ‘carer’ and ‘environment’ are addressed in other ‘person-centred’ models, but the explicit emphasis of these features within DICE is different as it is aimed at own-home settings. Therefore, carers in DICE receive a similar level of focus of attention as the patient does, i.e. the carer is also in receipt of treatment. Furthermore, DICE presents a flow diagram that identifies key components and their relationships, a mechanism of change, and builds assessment and management strategies around these structures.

Despite these positives, DICE has a number of shortcomings. First, it was developed for people with dementia (and their families) in their own homes, and not for those living in care, and as a result it is more limited in scope. The DICE approach does not formally support the use of a formulation, and so it is unclear about how the information it gathers is integrated and prioritised. Its lack of a clear end-product or care plan runs the risk of producing a confused set of recommendations. A final difficulty is that the DICE approach is trademarked, meaning its use may be restricted and it can neither be adapted nor supplemented with materials or tools.

A new model: ACME

Although the above management techniques (stepped care and DICE) are useful, we have found them to be impractical to use clinically and therefore consider it necessary to present a new framework for the management of BPSD. Nevertheless, in the new approach we have clearly borrowed from stepped care and DICE and also from the rest of the work discussed above. We have named the new model ACME. The acronym represents the four stages of our approach (assess, conceptualise and care plan, manage, evaluate) and is the Greek for ‘the peak of perfection’. The term was also used in the Looney Tunes cartoon series Road Runner, where it represented the company that supplied Wile E. Coyote with ideas and tools to capture the elusive Roadrunner.

In terms of the stepped-care model, ACME is best positioned at step 4. Before utilising ACME there are three categories of response one should employ, which are not strictly hierarchical. The first category is the use of good basic communication skills – a style that we refer to as ‘customer care’ skills (James Reference James and Jackman2019). This involves being polite, trying to see the other person's perspective, negotiating, etc. These simple verbal and non-verbal processes are often highly effective in reducing agitation and maintaining and restoring the person with dementia to a state of well-being.

If these types of approach are not effective, many caregivers can employ a slightly more sophisticated set of responses. A range of techniques and protocols can be utilised, such as distraction, delaying techniques, de-escalation and therapeutic lying (James Reference James and Gibbons2021). The caregiver may also refer to the GP to check for physical difficulties.

The third category of responses are anticipatory in nature. They attempt to use forward planning to deal with scenarios (such as intimate care interventions) that commonly trigger BPSD. Caregivers are aware that their actions during intimate care may trigger aggression, embarrassment or shame in the person with dementia: hence, specific coaching may be required to help promote dignity (and reduce distress) during such tasks.

In most situations, the BPSD that arise on a daily basis are dealt with through skilful application of these three categories of response.

The ACME approach is only required when good communication and de-escalation skills and protocols have proven unsuccessful in reducing the severity of the behaviours, meaning that a more thorough assessment and functional analytical approach is required. It is worth noting, however, that all of the processes described are integral to the use of ACME. The only feature that is unique to ACME is its framework, which allows clinicians to use the communication skills and protocols in a more systematic and targeted manner (i.e. the approaches are packaged in a more bespoke way for each individual).

The ACME framework incorporates unmet needs at its centre. Consider the flow diagram in Fig. 2. It suggests that the needs are influenced (moderated) by the individual requirements of the person and their caregivers. The needs in this model are mediated by (a) the degree of emotion and drive associated with satisfying the need and (b) the abilities of the person with dementia to meet the need themselves. On the left-hand side of the diagram we have a scenario where a person has both the cognitive and physical abilities to satisfy their needs; ‘satisfying’ in this sense means being able to physically or intellectually achieve desired goals or outcomes. In cognitive terms this would suggest that the person can form an intention, carry out goal-directed behaviour, problem solve or have sufficient insight to know they cannot meet the goal at this moment. In contrast, on the right-hand side we have a person with cognitive impairment. They may no longer have the problem-solving or attentional abilities to satisfy their needs. A lack of insight might compound the problem, with the person no longer able to recognise that their needs cannot be met. The lack of insight, combined with the unmet needs, is likely to bring the person into a confrontational situation with their caregivers. It is relevant to note that the person on both the left- and right-hand sides of the diagram will be engaged in multiple behaviours. However, because of the greater level of impairment of the person on the right, fewer appropriate problem-solving attempts will be used and a higher percentage of their behaviours may be deemed ‘unacceptable’ and ‘challenging’.

FIG 2 Conceptual model describing the mechanisms associated with needs-based behaviour in dementia. Beh, behaviour.

The moderating features of this model (the person and the caregivers) are influential in how the BPSD are interpreted and managed. Therefore, they require some form of assessment.

Person factors

The person engaging in the BPSD is clearly a focus of any treatment regime (Hughes Reference Holle, Halek and Holle2016). Important person-centred factors include the person's: physical health, psychological well-being, medication regimen, needs, personality, strengths/resilience, coping style, cognitive deficits, current outlook/reality, access to meaningful activity and relationships.

Carer and interpersonal factors

It is important to assess the role of the caregiver from two related perspectives. The first is an examination of the interpersonal and communication style of the carer. This is particularly relevant in the management of BPSD because, as noted earlier, the caregivers are the ‘agents of change’ in many of the treatment strategies. However, a feature that is not always given the appropriate attention is the further requirement to undertake a formal assessment of the personality, mental and psychological health of the caregiver. This is most apparent when working with people in their own homes but is also relevant in residential and nursing care settings because they are sometimes stressful places to work. Various papers (e.g. Moniz-Cook 2000) highlight that cultural factors such as job satisfaction and perceived management support dictate how capable staff feel in coping with distressed behaviours. In all of these situations the well-being, or ill-being, of the caregiver should be considered.

The four phases of ACME

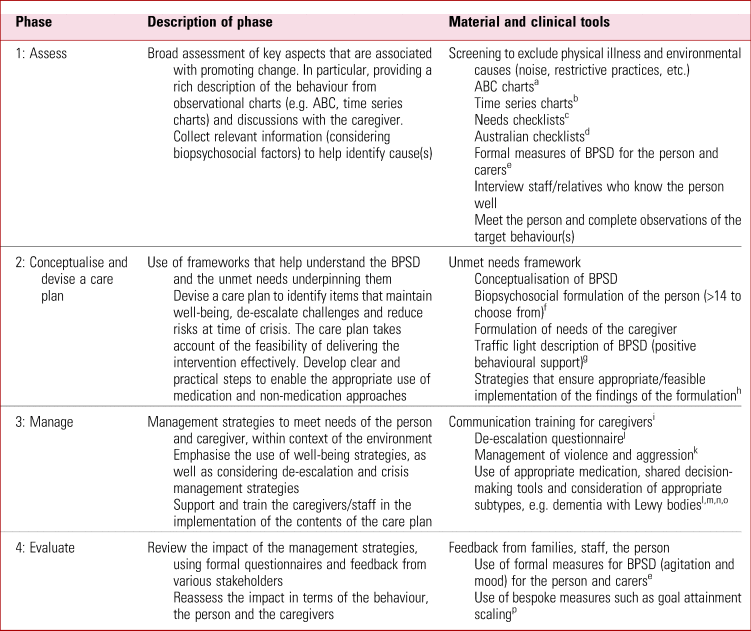

The ACME framework is summarised in Table 1. It is important to highlight that the agents of change in this framework are the caregivers and thus they are vital in each phase.

TABLE 1 An overview of the ACME (assess, conceptualise and care plan, manage, evaluate) framework for the management of behavioural and psychological symptoms of dementia (BPSD)

ABC, antecedence, behaviour and consequence.

a. Leeds Integrated Dementia Board (Reference Jennings, Ramirez and Hays2018): pp. 19–20; b. Duffy (Reference Cohen-Mansfield2019); c. Smith (Reference Smith, Hadaway and Reichelt2016); d. McCabe (Reference Kales, Gitlin and Lyketsos2015); e. Dunn & Moniz-Cook (2019); f. Holle (Reference Dunn and Moniz-Cook2016); g. Sells (Reference Sells and Shirley2010); h. James (Reference James and Jackman2019); i. James (Reference James and Jackman2019); j. James (Reference James, Medea and Reichelt2021); k. Howarth (Reference Feast, Moniz-Cook and Stoner2016); l. International Psychogeriatric Association (Reference Howarth, Crooks, Sells, James and Jackman2015); m. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (Reference Moniz-Cook, Swift and James2012); n. DIAMOND-Lewy Team (Reference Moniz-Cook, Swift and James2012); o. Taylor (Reference Sells and Shirley2020); p. Jennings (Reference James and Birtles2020).

Phase 1 – Assess

The initial phase of ACME is to assess the needs of both the caregiver and the person with dementia, assessing their emotions, abilities and surroundings to identify causes for the BPSD. An initial biopsychosocial screening should be carried out to rule out any physical or environmental causes for the behaviour (e.g. infection or noise levels). During this initial phase, the caregiver can help in providing rich descriptions (using ABC and time series charts where appropriate: Table 1) to enable the clinician to gain a clear understanding of the BPSD.

Phase 2 – Conceptualise and devise a care plan

The second phase of ACME is split into two interlinked components; first to conceptualise the BPSD and second to devise a care plan. One should conceptualise the BPSD using frameworks that help to understand behaviours and the unmet needs underpinning them, drawing on the unmet needs framework and the conceptual model of understanding BPSD (Fig. 2). Irrespective of the framework chosen, it is important that biopsychosocial data gathered during the assessment phase are distilled into a clear and digestible written or visual summary.

A care plan should then be devised, identifying features that currently aid the well-being of both the person with dementia and the caregiver and help to de-escalate challenges and reduce risks at times of crisis. The care plan should take into account the feasibility of delivering the intervention, i.e. how realistic it is for the caregiver to be able to do it consistently and effectively. To aid with the structure of the care plan, concepts from positive behavioural support (e.g. the traffic light analogy; Sells Reference Sells and Shirley2010) are important. Indeed, knowing how to keep people in the ‘green’ stage (maintained by proactive intervention) is just as important as planning what to do in both the ‘amber’ (reactive intervention) and ‘red’ (contingency intervention) stages of the BPSD.

Phase 3 – Manage

The third phase of ACME is to employ techniques to ‘manage’ the BPSD, meeting the needs of the person and the caregivers. The carer, clinician and person with dementia should work collaboratively to identify appropriate interventions to help manage the BPSD, appreciating the need to tailor interventions depending on what stage of the cycle the person is in. It is in this phase that support and training for caregivers is crucial to implementing the content of the care plan. Appropriate training should be delivered, supporting the use of both well-being strategies and de-escalation techniques. The training is best delivered in the form of coaching because many of the skills involved in formulating, constructing and delivering of care plans are difficult to attain and require support and scaffolding. A coaching programme called communication and interaction training (CAIT) has been designed to support the delivery of ACME (James Reference James and Jackman2019) and an online version of this programme is being launched in spring 2021. CAIT contains qualitative and quantitative measures for evaluating its impact in relation to both the person with dementia and their carers.

Phase 4 – Evaluate

The final phase of ACME is to evaluate the impact of the interventions employed in the management phase for both the person with dementia and the caregivers, i.e. how feasible the interventions were and how they affected the BPSD. This can be achieved using formal questionnaires and discussions with various stakeholders (families, friends, staff, etc.). This information should then be fed back into the framework and alterations made to the management interventions if necessary.

A few words on the conceptualisation

Figure 3 shows that the key aspect that informs all the ACME framework is the conceptualisation. The conceptualisation involves the integration of three perspectives: (a) the unmet needs, (b) the mechanisms through which the BPSD occur and (c) the formulation, which takes account of the person's and the caregiver's needs. This central aspect informs all the other aspects of ACME (i.e. what should be assessed, contents of the care plan, the treatment strategies and their evaluation).

FIG 3 Structural representation of the ACME (assess, conceptualise and care plan, manage, evaluate) framework for the management of behavioural and psychological symptoms of dementia (BPSD).

The conceptualisation depicted for ACME in this article reflects the philosophy and approach towards BPSD (James Reference Hughes and Beatty2017) being used by the majority of the current authors, and best practice guidelines (James 2018). It is worth noting, however, that clinical teams and units holding different conceptual views of BPSD to the ones expressed in this article will employ the treatment regime consistent with their own views.

Let us consider two scenarios relating to the treatment of BPSD by two mental health in-patient units.

Unit 1 – this in-patient unit follows the version of ACME described in this article. The approach is coordinated and interlinked from assessment to evaluation. All patients receive a needs-led formulation, family members are consulted and assessed. Biopsychosocial care plans are written and implemented, and the impact of the management strategies is assessed holistically in relation to the person with dementia and their family. The work is supported by worksheets and instructive animations which outline the philosophy of the approaches used (James Reference James and Moniz-Cook2020).

Unit 2 – this in-patient unit's conceptual view regarding the treatment of BPSD is a more restricted biological perspective, focusing on physical health and psychotropic drug treatments. The team does not employ formulations, but uses comprehensive ‘medication’ care plans based on an assessment of the nature of the BPSD and underlying physical health presentations. The main management strategies are medication, and evaluation is seen through the prism of the balancing of the beneficial effects versus the adverse side-effects of the drugs.

These two scenarios highlight the advantage of the more holistic perspective, which provides a far greater range of treatment methods consistent with the aetiologies and presentations of BPSD. The comparison between scenarios illustrates the key role played by ‘conceptualisations’ in directing treatments. Indeed, it suggests that all clinical teams need to reflect on their conceptualisations and philosophical approaches to BPSD. To achieve good consistent clinical practice all members of a clinical team should be clear about these perspectives, and the conceptual beliefs should be shared with families, stakeholders and, where possible, the people with dementia.

Summary

ACME is a system for coordinating the delivery of effective management strategies for the treatment of BPSD. When following best-practice principles it is a person-centred and holistic approach, incorporating many of the features discussed in this article:

• it incorporates the unmet needs perspectives;

• the framework utilises the ‘conceptual model for BPSD’ and so ensures that behaviours are not over-pathologised and that only genuinely ‘problematic’ behaviours are treated;

• the use of a comprehensive assessment phase at the outset of the ACME process allows any physical and environmental problems to be addressed early; this may result in a particular behaviour being resolved or reduced; at the very least, the information gathered from the assessment phase can be utilised in the conceptualisations;

• it supports the use of biopsychosocial formulations that also consider the needs of the caregivers;

• the design of the management strategies highlights that the caregivers are the ‘agents of change’;

• ACME incorporates some of the notions of a stepped-care approach, and emphasises the key role that good communication skills play in the management of BPSD;

• ACME can be used in both home and in-patient/residential settings, which is a critical difference compared with the DICE approach, which deals exclusively with ‘own home’ scenarios.

Conclusions

This is a rather wide-ranging article, moving between medication, frameworks, formulations and care planning, and finally considering some existing and newer conceptual models. The new model that we propose – dubbed ACME – clearly requires further development. Nevertheless, the series of arguments that we present here have led us to conclude that there is a place for such a holistic approach. We have unashamedly borrowed from other sources and credited this work. During our construction of the ACME model we have been ever mindful of the need to produce ‘informed actions’ which are sufficiently specific that clinicians, at whatever level, can implement the suggestions directly. Indeed, we believe that too many previous reviews and guidelines have failed to be sufficiently practical and concrete in terms of what actions to undertake to manage BPSD. As a consequence, the existing literature has not always enabled clinicians to apply its recommendations directly to their practices, resulting in a status quo regarding management strategies used in care homes and wards. It is envisaged that when the next national guidelines for BPSD are being produced, the panels of experts will have holistic programmes similar to both ACME and DICE to draw on in order to provide clearer guidance about effective psychosocial interventions as alternatives to psychotropic medication.

Author contributions

All authors contributed substantially to the writing of the article and its conceptual underpinnings. The initial ideas and framework were conceived by I.J. and K.R., revisions were chiefly undertaken by I.J. and K.R.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Declaration of interest

None.

ICMJE forms are in the supplementary material, available online at https://doi.org/10.1192/bja.2021.12.

MCQs

Select the single best option for each question stem

1 NICE's guidelines on the management of BPSD recommend that antipsychotics:

a are used for everyone with BPSD

b are discouraged entirely

c are always preferred to benzodiazepines

d are used with caution, owing to their expense

e are used with caution, owing to their potential for problematic side-effects.

2 Formulation for BPSD:

a is always shared with the person with dementia

b is used solely to direct the prescribing of medication

c is most appropriate for treating the mood element of any presentation

d is inappropriate for people with severe dementia

e provides a holistic perspective, examining the biopsychosocial nature of the person's presentation.

3 The stepped-care model in dementia is:

a an evidenced-based exercise treatment for people with dementia

b a treatment programme outlining four stages for the management of BPSD

c designed to treat carer distress

d used exclusively in care homes

e a recently developed physiotherapy measure for the assessment of mobility.

4 BPSD stands for:

a behavioural and psychological symptoms of dementia

b British Psychiatric Society of the Dementias

c behavioural problems seen in dementia

d best-practice services for dementia

e Brit-list of psychotropic side-effects of drugs.

5 ACME is:

a the name of a famous randomised controlled study concerning the treatment of BPSD

b a company providing restraint equipment in dementia care

c a model for the management of BPSD, involving assessment, conceptualising, managing and evaluating processes

d an occupational therapy programme for assessing sensory abilities in dementia care

e a form of music therapy used to treat depression in people with dementia.

MCQ answers

1 e 2 e 3 b 4 a 5 c

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.