Family therapy involves working with the significant others as well as the patient – in other words, it focuses on the relationships within which the patient's problem behaviours/symptoms are manifested – and it is also known as systemic therapy. The term family intervention is often used when working with the families of people with schizophrenia and other psychoses. Non-systemic family interventions are often contrasted with family therapy by describing them as family management or family psychoeducation (Box 1; Burbach Reference Burbach1996) to reflect their focus on education and skills development to improve coping and reduce stress levels. The historically distinct systemic and psychoeducational approaches are increasingly being integrated (Bertrando Reference Bertrando2006; Lobban Reference Lobban and Barrowclough2016) and this article presents a collaborative resource-oriented integrated family intervention for working with families and wider support networks. Its main objective is to move beyond the historical theoretical debates to provide basic guidelines (Table 1) and a clinically useful framework to enable family intervention in practice.

Box 1 Family intervention approaches

Family therapy/systemic therapy

• Individualised, family-needs led, solution-oriented therapeutic sessions in which new meanings/narratives are co-constructed.

• Causality is viewed as circular and sessions focus on family interactions (particularly maintenance cycles) and mutual reappraisal, which often involves exploration of family beliefs, including intergenerational and societal beliefs.

Family management/psychoeducation

• Structured approach adapted to the needs of individual families following an assessment, in which coping skills are developed and the family are encouraged to make informed choices about what would be helpful for all of them to stay well.

• The family's stress levels are reduced through increasing understanding about what the patient is experiencing and how they can be helped, and by developing communication and problem-solving skills.

TABLE 1 Some basic guidelines for family intervention in psychosis

Rationale for working with families with psychosis

In light of the disabling effects of psychosis on a person's functioning it is not surprising that there is considerable evidence that family members and other individuals within the support network are adversely affected both at the first episode of psychosis and when supporting people experiencing long-term disability (e.g. Fadden Reference Fadden, Bebbington and Kuipers1987; Patterson Reference Patterson, Birchwood and Cochrane2005; Onwumere Reference Onwumere, Kuipers and Bebbington2011a) and that family interventions lead to significantly improved clinical outcomes and are cost-effective (e.g. Mihalapoulos Reference Mihalopoulos, Magnus and Carter2004; Bird Reference Bird, Premkumar and Kendall2010; Pharoah Reference Pharoah, Mari and Rathbone2010).

Numerous clinical guidelines (Bertolote Reference Bertolote and McGorry2005; Dixon Reference Dixon, Dickerson and Bellack2010; IRIS 2012; Worthington Reference Worthington, Rooney and Hannan2013; National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health 2014) therefore explicitly recommend actively supporting families and involving them as partners throughout the care pathway, with a particular emphasis on active engagement with relatives from the patient's first contacts with services (creating a ‘triangle of care’) as well as formal family interventions.

Evidence supporting the involvement of significant others in mental health treatment can also be found in the systemic therapy and couples therapy literatures (von Sydow Reference von Sydow, Beher and Schweitzer2010; Stratton Reference Stratton2011; Baucom Reference Baucom, Whisman and Paprocki2012). Of particular relevance to the integrated family intervention presented in this article is the solution-focused brief therapy (SFBT) literature. This is a well-developed systemic therapy that explicitly focuses on the patterns of interaction most directly relevant to the symptom, paying particular attention to solutions (‘noticing what already works’) and using techniques such as miracle questions, scaling and focusing on exceptions (de Shazer Reference de Shazer1985; Trepper Reference Trepper, McCollum, De Jong, Franklin, Trepper and Gingerich2012). A systematic review of 43 studies concluded that they provided ‘strong evidence that SFBT is an effective treatment for a wide variety of behavioural and psychological outcomes and, in addition, it appears to be briefer and less costly than alternative approaches’ (Gingerich Reference Gingerich and Peterson2013: p. 281). The reader will see that the integrated brief family intervention described in this article contains many aspects of SFBT. Open dialogue, a radically different mental health service which has been developed in Finland, arguably provides even stronger evidence for a family-/network-based approach (Seikkula Reference Seikkula, Alakare and Aaltonen2001, Reference Seikkula2003). This service, which is based on a family/network crisis intervention and minimises use of psychotropic medication, has achieved remarkable clinical and functional outcomes (Seikkula Reference Seikkula, Aaltonen and Alakare2006).

Historical development of family interventions

It is worth making a brief comment on the historical developments in the field of family intervention. Family practitioners from both systemic and non-systemic traditions have moved from an initial position that therapists, as ‘experts’, should re-educate family members or restructure family relationships to a more collaborative ‘post-modern’ acknowledgement of the subjective nature of reality, the need to work within people's belief systems and the importance of reflexivity. This shift to a constructivist/social constructionist approach predominates in the field of family therapy (Dallos, Reference Dallos and Draper2010), but it can also be seen in the cognitive–behavioural therapy (CBT) field with the development of concepts such as ‘radical collaboration and acceptance’ and a focus on strengths and solutions (e.g. Chadwick Reference Chadwick2006; Rhodes Reference Rhodes and Jakes2009; Padesky Reference Padesky and Mooney2012). Recently a number of these therapeutic approaches have been categorised as ‘resource-oriented therapeutic models’ (Priebe Reference Priebe, Omer and Giacco2014).

Historical differences in the family intervention field have also narrowed because there is now greater understanding of the processes underlying empirical measures of distress and family tension (Kuipers Reference Kuipers, Onwumere and Bebbington2010; Burbach Reference Burbach, Gumley, Gillham and Taylor2013a). The early family management/psychoeducation approaches had a primarily linear focus on increasing knowledge about the illness, medication concordance and the teaching of communication and problem-solving skills. This was based on the ‘expressed emotion’ research literature, which had identified that the family's critical/hostile or overintrusive behaviour towards the patient was significantly associated with increased relapse rates. Although there is a wide range of possible family dynamics and these change over time, it is interesting to note that this substantial body of research basically identified three common caregiving relationship patterns in psychosis: ‘positive’, ‘overinvolved’ and ‘critical/hostile’. Although the first should be encouraged, different therapeutic responses are required to reduce mutual dependency (e.g. encouraging an overprotective parent to back off and reinforcing a patient's steps to greater practical and emotional independence) and cycles of mutual criticism or criticism-and-withdrawal (e.g. encouraging mutual understanding; practising positive communication). It is worth noting that, while both overinvolved and critical/hostile styles of interaction are clearly associated with poor clinical outcomes, these research findings have not been replicated across all cultures (Cheng Reference Cheng2002) and it is now recognised that these ‘expressed emotion’ styles reflect normal coping strategies and develop over time (Patterson Reference Patterson, Birchwood and Cochrane2005; McFarlane Reference McFarlane and Cook2007; for a detailed review see Burbach Reference Burbach2013a). Normalisation is therefore often a useful therapeutic intervention.

Although psychoeducational family interventions had their origins in working in a more linear, manualised way (using a standard package) with people with long-standing disability resulting from psychosis and its treatment, contemporary psychoeducational approaches are based on assessment and formulations developed with individual families and there is thus a new consensus (among proponents of systemic family therapy and of psychoeducational family intervention) that therapeutic interventions should be tailored to the individual family's needs (the problems they are concerned about). This is especially the case when working with families coping with early psychosis, when it is important to focus on the emotional distress and to discuss psychotic symptoms rather than diagnosis (Gleeson Reference Gleeson, Jackson, Stavely, McGorry and Jackson1999; Burbach Reference Burbach, Fadden, Smith, French, Read and Smith2010; Onwumere Reference Onwumere, Bebbington and Kuipers2011b).

A clinical approach

In this section I give a ‘nuts and bolts’ description of a flexible integrated approach to working with families and wider support networks. At the heart of this focused resource-oriented approach is the collaborative therapeutic relationship in which everyone's views are valued and respected. If the therapist creates a sufficiently safe space, the patient and family/network members will be able to share their thoughts and feelings and find more effective solutions to their current concerns. During such conversations it often becomes clear that significant others have inadvertently reinforced the patient's problem behaviours and that the whole system can be enabled to change unhelpful interactional patterns through shifts in their beliefs, appraisals of one another's motives and actions, and by practising new behaviours. In previous publications my colleagues and I have described this as a ‘cognitive interactional’ approach (Burbach Reference Burbach and Stanbridge2006).

This brief collaborative systemic intervention can be described in terms of seven overlapping phases:

1 the sharing of information and provision of emotional and practical support

2 identification of patient, family and wider network resources

3 encouraging mutual understanding

4 identification and alteration of unhelpful patterns of interaction

5 improving stress management, communication and problem-solving skills

6 coping with symptoms and relapse prevention planning

7 ending.

Phase 1: The sharing of information and provision of emotional and practical support

At times of crisis, such as when a family member develops psychotic symptoms, relapses or exhibits an extreme behaviour, other family members are often in a state of ‘shock’, feeling confused, overwhelmed, upset, despairing or angry. Their attempts to get help have often been frustrating and they may have had traumatic experiences due to their loved one's reactions to services, compulsory admissions, contacts with police and so on. The reactions of the wider community because of the stigma still surrounding mental illness often compounds both the patient's and the family's sense of hopelessness.

The most important first step in any family intervention is therefore to provide family members with tailored support and information. Providing families with emotional support primarily involves listening to their experiences and validating them. This often involves undefensively accepting that the family feels that they have been let down by gaps or inadequacies in mental health services. Normalising their reactions to these traumatic events is the next essential step, before exploring their understanding and offering information in order to help them feel more empowered to cope. This approach is sometimes called psychoeducation (Xia Reference Xia, Merinder and Belgamwar2011), to differentiate it from other forms of therapy, but there is a danger that clinicians might see their role as ‘teachers’ and that the family will feel ‘talked down to’ and disempowered (Szapocznik Reference Szapocznik and Williams2000). What is required is much more than a ‘fatherly lecture’ or the provision of information leaflets; and if leaflets are used, they should simply be adjuncts to the process. What needs to occur is a conversation in which the clinician finds out how the different family members make sense of the psychotic experience and helps them to build on this foundation so that they develop a more coherent, helpful understanding. For example, in one family session we had a useful discussion about psychosis by exploring the patient's description of it as ‘a scary monster’ and the family members' view that in using this description, she was adopting a childlike persona and playing a role. This led them to make a connection with their regular game of playing different characters and speaking in different accents during family meals. A subsequent exploration of the way in which some members of the family were very expressive with their anger, whereas others denied and avoided such feelings, led to a helpful understanding of the psychosis as a way of expressing unbearable feelings. In essence, this is a therapeutic process rather than an educational one and the clinician should resist the temptation to impose their own framework of understanding:

‘in particular professionals should not insist that people agree with the view that experiences are symptoms of an underlying illness. Some people will find this a useful way of thinking about their difficulties and others will not’ (Cooke Reference Cooke2014: p. 105).

Many people make sense of their experiences as a response to life's stressors and trauma, or in terms of a spiritual experience, and find such personalised understandings more helpful than an ‘illness model’ in regaining optimum functioning following an episode of psychosis. It is often helpful to introduce an overarching framework such as the stress–vulnerability model (Zubin Reference Zubin and Spring1977), but in doing so the clinician's role is to tentatively and respectfully provide information that helps to develop family members' personal understandings of the psychosis rather than give a crash course in psychiatry. There is also a great deal of general information that can helpfully be shared – information about services, what to do in a crisis, additional sources of support, etc.

Phase 2: Identification of patient, family and wider network resources

Besides listening and acknowledging problems that are facing the family, it is also important to take any opportunity to identify each individual's strengths and competencies. Solution-focused therapy, narrative therapy and other competency-based therapeutic techniques are useful in this regard (Bertolino Reference Bertolino and O'Hanlon2002). For example, a clinician might comment ‘You are coping really well with…’ or ‘What did you draw on to find the strength to go on at that point?’ In the initial meeting(s) it is useful to explore the potential contributions of members of the family/wider network and the things that they have tried to do to help (‘attempted solutions’). During times of crisis, when the patient may be acting irrationally and may even present a danger to themselves or others, the wider network can be an invaluable resource. It is often important to keep an eye on the patient and help them to occupy their time, but this can become unhelpful if the patient feels overly scrutinised or pressured. Some members of the network may have less complex relationships with the patient and may be better suited to take on this task, or they may be able to help share it.

Besides harnessing the network to solve particular problems and taking any opportunities for reinforcing competencies, it is also important to notice exceptions to problems and when individuals – patients or family members – have found solutions to their problems (e.g. ‘It is good to hear that there are times when x is able to ignore the intrusions of the voices’). People often report partial solutions to problems but discuss them as failures. By gently exploring these the clinician can help individuals to recognise that they are able to deal with their difficulties and thereby encourage them to renew their efforts. Often people only partially implement a potentially useful strategy is because they expect it to fail. Any discussions that increase the patient's and significant others' sense of agency and hope for the future will be therapeutically useful and this should be the overarching aim of the clinician.

Phase 3: Encouraging mutual understanding

Relationships often become fraught when a family member develops the confused thinking, perceptual abnormalities, fears, withdrawn or odd behaviours, or lack of interest in everyday activities that are commonly associated with psychosis. A brief intervention is most likely to be effective if available as early as possible, before these problems have become entrenched. Systemic therapists refer to families/networks that have changed and adapted to the new stressful situation as ‘trauma-organised systems’ (Bentovim Reference Bentovim1996). Trauma-organised systems are often unhealthy for all concerned: family members commonly become angry, critical or hostile, and the patient becomes angry and fights back or, more often, withdraws (and in both cases is more likely to relapse). Alternatively, family members may become overly fearful, watchful and overintrusive, so that the patient feels ‘smothered’ and may become stuck in a ‘chronically disabled role’. The patient is more likely to have a further episode of psychosis and the family members are more at risk of developing common mental health problems such as anxiety and depression.

Besides creating a safe space for all family/network members to express their fears, frustrations and other feelings and for the clinician to respond with active listening, validation and other general (non-directive) counselling skills, family/network sessions offer the opportunity to increase mutual understanding. As a first step, the clinician should try to get each person present to express their thoughts and feelings. This will require facilitation skills, with the clinician ‘bringing in’ the different contributors and making sure that no one feels silenced and no one dominates the conversation. This role can be likened to that of the conductor of an orchestra – most of the time only a light touch is required, for example using humour, asking a question or reflecting on a process in the room (Stanbridge Reference Stanbridge, Burbach, Froggatt, Fadden and Johnson2007; Burbach Reference Burbach and Diggins2016a). On some occasions a firmer, more active approach is needed to steer the conversation. The clinician should stop discussions that are excessively blaming or otherwise harmful if the family members do not appear able to do this themselves. Although clinicians should adopt a respectful, curious and non-judgemental stance when working with families and should remain open-minded about things that are discussed and when exploring whether or not these are helpful to the individual and their family, this does not mean ignoring their own ethical or moral values. If this respectful exploration reveals exploitation, abuse or any other harmful behaviour this should be addressed in the sessions and appropriate safeguarding or law-enforcement procedures followed.

A safe conversation in which everyone feels heard and validated is often a powerful emotional experience and in itself can be enough to help people to develop more positive, mutually supportive relationships. I often find that a family session is the first time that the person has revealed the extent of their psychotic experiences and the resultant distress and this leads to a significant shift in family atmosphere. Sharing these experiences can lead to discussion about how the individual would prefer family members to respond, as well as the refinement of coping strategies (see also phase 6).

It is recommended that the clinician comments on any positive aspects of family/network relationships, as this can benefit the emotional atmosphere in the session and help to move sessions forwards to a point where the family members feel more empowered and able to cope and solve problems. It is therefore useful to make observations such as: ‘You are a close, supportive family’, ‘That really shows how much you care for x’ or even ‘The fact that you are here today shows that you care and want to help’. However, sometimes the clinician will need to explore issues in more detail and to address more explicitly an unhelpful interactional pattern (see phase 4).

Comment

I find that as little as one session, encompassing phases 1–3, can be an effective brief intervention. This can be conceptualised as helping the family ‘back on track’ and is most likely to suffice if the family members have previously had reasonably positive relationships and if the family's unhelpful coping strategies have not yet become ‘set in concrete’. However, even in cases where it has been possible to intervene early, it is often necessary to provide further sessions as part of a brief intervention. These would often involve addressing unhelpful family patterns and enhancing coping skills.

Phase 4: Identification and alteration of unhelpful patterns of interaction

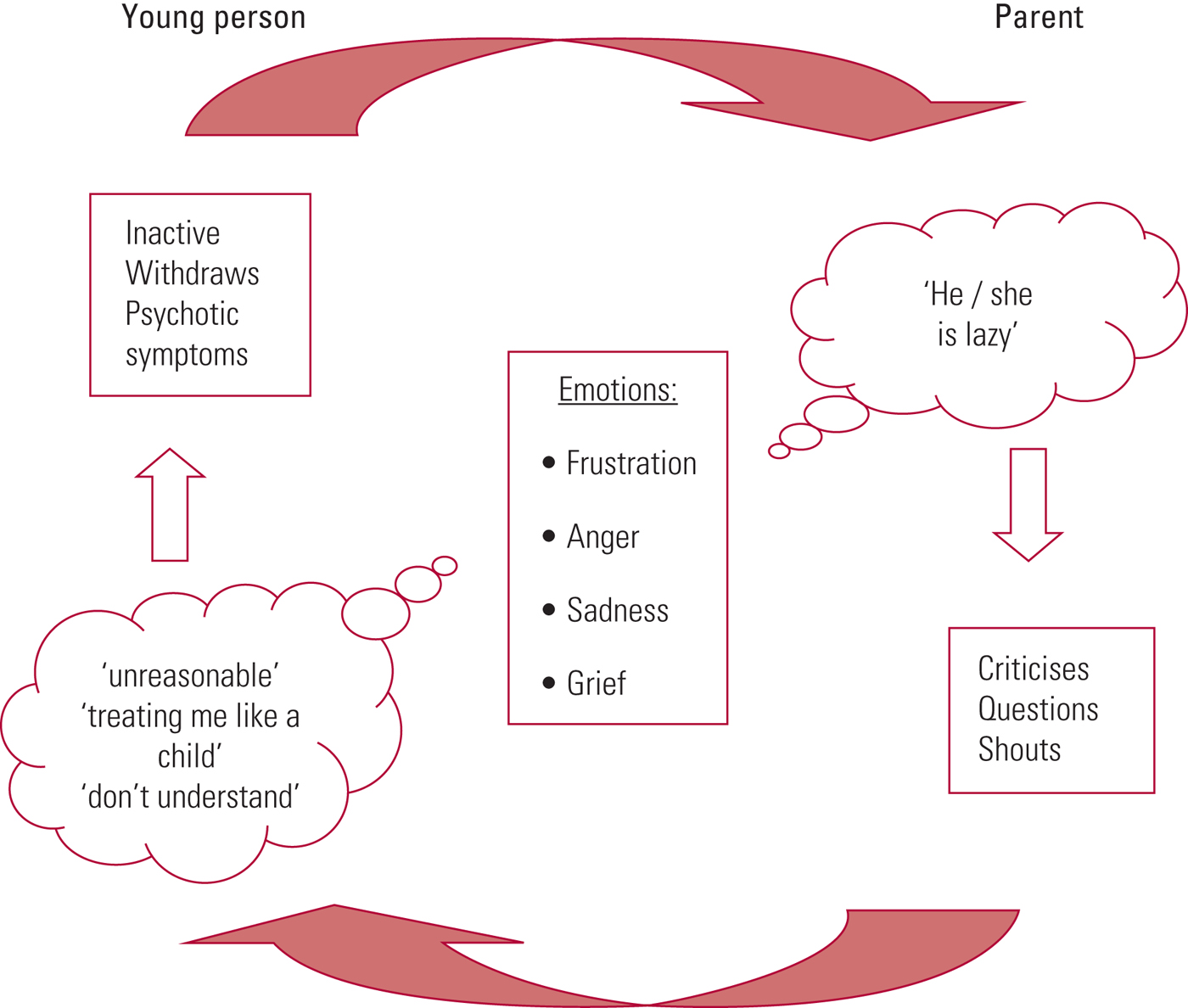

When family members report their problems in a generalised (and blaming) way it is useful to explore specific situations and help the family to recognise that they are all contributing to, and are stuck in, a repeating pattern or ‘vicious cycle’. An exploration of sequences of behaviours (or ‘circularities’) regarding specific incidents (e.g. ‘Let's look at what happened yesterday evening’) enables the identification of the feelings, beliefs and actions of the participants. The clinician, working with the family, can draw a ‘cognitive interactional cycle’ clarifying a (problem) behaviour, the circumstances leading up to it and the appraisals, emotional reactions and responses to it. An example of a cognitive interactional cycle is shown in Fig 1 (other common examples are detailed in Burbach Reference Burbach, Gumley, Gillham and Taylor2013a).

FIG 1 An example of a cognitive interactional cycle.

As mentioned previously, the exploration of such cognitive interactional cycles can be a powerful therapeutic experience as the different family members realise that they have been misinterpreting each other's motives and have inadvertently been reinforcing the problem behaviour. This technique not only results in increased mutual understanding and a consequent improvement in the emotional climate in the family, but can also help identify specific targets for intervention. In the example shown in Fig 1, working with either party could enable a new, more positive interactional cycle to develop. Behavioural techniques with the patient (such as goal setting and positive reinforcement of approximations of the desired behaviour) and communication training with the parent could help the patient to become more active and less withdrawn, and the parent to become less critical. Focusing on their appraisals of each other (exploring alternative understandings) is another avenue to engender helpful change. For the patient, a more helpful alternative cognition might be ‘He's getting upset with me because he's concerned/cares about me and wants to help’, and for the parent it might be ‘She is struggling with her symptoms and doing the best she can. I'll try to support her without pressurising her’.

If the exploration of interactional cycles is not sufficient and the ‘spontaneous’ alteration of feelings, beliefs and feelings does not occur, then more structured cognitive–behavioural skills training may be required, which brings us to phase 5.

Phase 5: Improving stress management, communication and problem-solving skills

It is often not enough to provide information about the stress–vulnerability model (phase 1) to reduce the emotional tension in the family (and reduce the likelihood of relapse and family members developing their own mental illness); helping them to develop specific stress management skills is often required. Techniques such as yoga, meditation, relaxation, exercise or simple breathing exercises (e.g. 7/11 breathing – breathing in for a count of 7 and out for a count of 11) can be very useful. Different family members may be more or less receptive to these ideas, but a reduction in even one person's stress levels can benefit the overall family atmosphere and is therefore worthwhile. These activities can also help to strengthen couple or family relationships, so finding one that everyone is prepared to join in with is the ideal.

Some families with psychosis have specific communication difficulties (Doane Reference Doane, West and Goldstein1981), but many people experience stressful family interactions because of poorly developed communication skills and can benefit from practice, following guidelines for clear, direct and positive communication (Falloon Reference Falloon, Mueser and Gingerich2004). For example, rather than criticising, family members can practise calmly asking a person to carry out the desired behaviour: ‘It really makes me feel cross when you… Please do…’. Similar communication skills guidelines have been developed for active listening and expressing positive and negative feelings (Box 2).

Box 2 Communication skills training

Active listening:

• look at the speaker and attend to what is said

• nod your head, say ‘Yes’, ‘Uh-huh’

• ask clarifying questions (e.g. ‘What happened next?’)

• check what you heard (e.g. ‘So what you are telling me is…’)

Expressing positive feelings:

• look at the person

• say exactly what they did that pleased you

• tell the person how it made you feel

Making a positive request:

• look at the person

• say exactly what you would like them to do

• tell them how it would make you feel

• in making positive requests, use phrases such as:

○ ‘I would like you to…’

○ ‘I would really appreciate it if you would…’

○ ‘It's very important to me that you help me with…’

Expressing negative feelings:

• Look at the person: speak firmly

• Say exactly what they did that upset you

• Tell them how it made you feel

• Suggest how they might prevent this from happening in the future

Some families also find it helpful to improve their problem-solving skills. Giving families information about six-step problem-solving (Box 3) and helping them to practise it can provide a useful family ritual that can reduce stress and help prevent problems from becoming entrenched. Many families set a regular time each week for a family meeting in which problems are worked through, with family members rotating the roles of chairperson and scribe/secretary. This structured format enables difficult issues to be addressed in a safe way.

Box 3 Six-step problem-solving

Step 1: What is the problem or goal?

Talk about the problem/goal – get everybody's opinion, ask questions to clarify. Then write down the agreed problem/goal.

Step 2: List all possible solutions

What has worked in the past? What would a friend say? Get everybody to come up with at least one possible solution. Write down all ideas, even if you think they won't work. List the solutions without discussion.

Step 3: Consider pros and cons of each solution

Quickly discuss the main advantages and disadvantages (pros and cons) of each possible solution.

Step 4: Choose the solution that seems best

Choose the solution that can be carried out most easily to solve the problem.

Step 5: Plan how to carry out the best solution

Be specific: Who? What? When? Where? How?

What could cause problems and how could you get around this? What resources are needed? Practice difficult aspects. Plan time for review.

Step 6: Do it! Try out the solution and review the results

Did it work? Which aspects worked? Focus first on what worked well. Praise all efforts. Revise as necessary/try out another solution (return to steps 3 and 4).

(Based on Falloon Reference Falloon, Mueser and Gingerich2004)

Phase 6: Coping with symptoms and relapse prevention planning

Most people with psychosis and their relatives/friends are concerned about the possibility of relapse as well as any ongoing symptoms, and this often becomes the agreed focus for family sessions. Exploring the factors that led to the psychotic episode – predisposing (‘background issues’) and precipitating factors (‘triggers’) – as well as the sequence of prodromal and psychotic symptoms is very useful as a therapeutic technique. ‘Storying’ or ‘integrating’ the psychotic experience results in better outcomes than ‘sealing over’ or ‘burying it’, and it also enables the patient, family and professionals to identify specific warning signs of relapse and to agree an intervention plan should this ‘relapse signature’ occur again. In some services it is possible to agree ‘advance statements’ in which the patient specifies their preferred options for treatment should they become ill again. For example, they may express a preference for a specific medication or specify that a particular relative should be contacted even if, when acutely unwell, they are likely to say that no one should be told that they are in hospital.

It is also useful to use any opportunity to facilitate a conversation about symptoms and to encourage the development of coping strategies. In keeping with the collaborative solution-focused approach, this often involves the refinement of coping skills or ‘coping strategy enhancement’ (Tarrier Reference Tarrier, Harwood and Yusopoff1990). In some cases techniques from individual CBT for psychosis (Chadwick Reference Chadwick, Birchwood and Trower1996) can be used in parts of the family sessions, with the family members providing support during and between the sessions.

Phase 7: Ending

Whatever the components of the intervention, it is good practice to review progress and reflect on the ‘key learning points’ at the end of each session (‘How did you find today's session? Can you think of one thing that you can take away from our meeting today?’). A similar review and reflection on key points should be undertaken at the end of the course of therapy. It is also useful to encourage the family to make notes and/or to give them a bullet point summary of key points. This will help consolidate the work and also, if the family decides not to continue with the meetings, each session will feel like a completed ‘mini-intervention’.

It is also useful to discuss how new strategies can be maintained and to consider how to prevent or respond to ‘lapses’, especially at the end of therapy. For example, ‘What will you do if you notice your unhelpful habits/problems creeping up again?’.

What would this family intervention look like?

With some families the sessions can touch on all of the phases, even if the intervention is for only two or three sessions. However, in most cases the meetings will not be able to include the development of specific skills without an agreement to devote sessions to this work (and thus a longer series of sessions – typically up to ten – would need to be agreed). The sessions are led by the family's needs: the goals of therapy are mutually agreed, sessions always start by asking what people would like to ‘place on the agenda’ and the next session is agreed only at the end of the current one. There is thus no ‘standard’ or ‘expected’ length of intervention. In many cases 3–5 sessions prove sufficient to improve the emotional climate, help the family to (at least begin to) change some unhelpful patterns, solve some immediate problems, and feel prepared and supported should they need to access services again.

Brief family interventions can also be incorporated into routine practice such as monitoring visits by psychiatrists or care coordinators/case managers, by adding 5 or 10 min to the visit to focus on family intervention. This can be done by arrangement, but can also take place ‘spontaneously’ by involving a family member who happens to be present. A relational focus does not even require the individual to be present. Dr Narsimha Pinninti has described how a short telephone call to a patient's mother enabled a therapeutic conversation that resulted in a change in the mother and son's interactions regarding his paranoid utterances and a resolve to express more positive comments to each other (Burbach Reference Burbach, Pradhan, Pinninti and Rathod2016b).

Cultural considerations

It may be reasonable to assume that ‘collectivist’ and ‘individualist’ cultures hold differing views on the role of the family and that this may affect family participation and involvement with mental health services. Although clinicians need to be sensitive to such issues, most family members are likely to be highly concerned about their loved one and can be successfully engaged in services, especially if this is done early on.

Family interventions can be successfully adapted to a range of cultural contexts (National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health 2014), although there is some evidence that, with particular cultural groups, a structured behavioural approach can result in increased stress levels and worse outcomes (Telles Reference Telles, Karno and Mintz1995; Rosenfarb Reference Rosenfarb, Bellack and Aziz2006). However, the flexible approach described in this article is based on a collaborative therapeutic relationship, with the clinician adopting a position of respectful curiosity. Adopting a respectful, cautious, curious position (guarding against making assumptions about how people should live their lives) is essential, regardless of the patient's and family's cultural background.

Service considerations

The collaborative resource-oriented intervention described above should not be considered in isolation. It is most likely to optimise outcomes if it is central to the wider service (as in the Finnish open dialogue services mentioned above) rather than just an addition to standard care. How might this be achieved? Wholescale service redesign with an associated staff training programme will be unrealistic in many settings, although ambitious peer open dialogue pilot services are being launched in the UK (Razzaque Reference Razzaque and Stockmann2016). The incremental development of a ‘menu’ of family-based services is a pragmatic way to develop more family-centred practice. Another strategy is to develop a stepped-care family service (Burbach Reference Burbach and Anastassiou-Hadjicharalambous2012, Reference Burbach2013b, Reference Burbach2015) so that the needs of families can be met with the least intensive intervention, utilising the ‘sufficiency principle’ (Cohen Reference Cohen, Glynn and Murray-Swank2008). In the Somerset Partnership NHS Foundation Trust we have found that the employment of a few family specialists whose remit includes the training of frontline mental health staff in family-inclusive practice and family interventions has been very effective (Stanbridge Reference Stanbridge2012, Reference Stanbridge, Burbach, McNab and Partridge2014).

Technological options such as internet-based family intervention programmes and the use of smart phones and computer tablets also show great promise (Ben-Zeev Reference Ben-Zeev, Drake, Brian, Marsch, Lord and Dallery2015).

Conclusions

The family intervention described in this article has been simplified into seven phases, but it should be recognised that these are fluid: clinicians should not try to impose a structure on the family, but should instead construct a therapeutically useful goal-oriented conversation with families based on their main concerns. These may vary from session to session and it is therefore helpful to start each session by asking how they would like to use the time today.

Although the seven-phases framework can be a helpful guide, perhaps the greatest benefit of any therapeutic model is that it makes the clinician feel more secure and hopeful, and it is then possible for them to enable the regeneration of these feelings in the people they are trying to help. Hopefully, this article will encourage all clinicians, whatever their level of training, to engage and collaborate with families in their struggles with psychosis – that in itself will be greatly valued and is likely to lead to better outcomes.

MCQs

Select the single best option for each question stem

1 Which of the following is false with regard to family therapists?

a They focus on the relationships within which the patient's symptoms/ difficulties occur

b They believe that the family are the cause of the patient's problems

c They focus on strengths and solutions

d They enable mutual understanding and behavioural change as family members reappraise one another's motives and actions

e They believe that most problems are inadvertently being maintained within interactional patterns.

2 Which of the following is true regarding work with families/wider support networks:

a It is clinically effective but not cost-effective

b It should be delivered in accordance with the original family intervention research manuals

c It should be avoided as many family relationships are toxic

d It is appropriate for people experiencing long-term disability rather than the first episode of psychosis

e It should be tailored to the particular family's needs.

3 Which of the following is true regarding family interventions?

a Family intervention is a term that applies only to the more goal-oriented, directive therapeutic work with families in which a member has psychosis

b Family interventions should have a clear focus on the well-being of the patient; other family members' needs should be addressed separately

c Family management is an unstructured family intervention that involves psychoeducation, communication skills training and problem-solving skills training

d Research is increasingly recognising the importance of mutual appraisals and the resultant interactional patterns

e The original structured behavioural approaches are equally effective across all cultures.

4 Which of the following does not apply to collaborative therapeutic relationships with families?

a Family members and clinicians jointly agree the goals/objectives of the meeting(s)

b Everyone's views are valued and respected

c Patients should be advised that their psychotic experiences are symptoms of an underlying illness

d Family members' expertise is emphasised and they are encouraged to refine their existing coping strategies

e The usefulness of each session is reviewed with the family and further sessions are agreed on a session-by-session basis

5 Which of the following phases is not part of the integrated family intervention described in this article?

a Improving stress management, communication and problem-solving skills

b Coping with symptoms and relapse prevention planning

c Identification of patient, family and wider network resources

d Identification and alteration of unhelpful patterns of interaction

e Teaching families about the diagnosis of schizophrenia, the stress–vulnerability model and medication adherence.

MCQ answers

1 b 2 e 3 d 4 c 5 e

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.