Numerous studies conducted throughout the COVID-19 outbreak have suggested that girls and women are among those most vulnerable to adverse psychological effects related to stress (Pedrosa Reference Pedrosa, Bitencourt and Fróes2020). Among women of reproductive age, stress has been documented to be one of the main risk factors for irregular menstrual cycles, along with obesity, diabetes, smoking and polycystic ovary syndrome (Ansong Reference Ansong, Arhin and Cai2019). It has been suggested that COVID-19-related stress and associated stressors are potential determinants of women's gynaecological and mental health. Since female healthcare workers face an increased fear of becoming infected, experience a heavy workload, fatigue, stigma and unprecedented psychosocial stress, this is leading to higher risk of depression, anxiety, sleep and stress-related disorders in this population during the pandemic, with a positive association with menstrual irregularities (Takmaz Reference Takmaz, Gundogmus and Okten2021).

Moreover, women in South Asia are often a vulnerable, frail and marginalised group, particularly if they are from lower social classes, ethnic minorities or have disabilities. The coronavirus outbreak has deepened pre-existing inequalities, and the fallout has been severe.

Therefore, we provide a general overview of the extent of the problem among girls and women, especially healthcare workers, in South Asia, and suggest recommendations for a proper understanding and management of this public health challenge.

General overview

COVID-19-related stress can not only cause new-onset menstrual cycle disorders but also exacerbate pre-existing problems such as premenstrual syndrome (PMS). PMS is characterised by emotional and somatic symptoms occurring within the luteal phase of the menstrual cycle and impairing normal daily functioning. According to the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists’ criteria, PMS can be diagnosed when a woman reports at least one affective and one somatic symptom from a list (six of each type) during the 5 days before menses and during the prior three menstrual cycles (Hofmeister Reference Hofmeister and Bodden2016).

Current situation in healthcare workers

Globally, around 70% of healthcare workers are women, and these professionals are being exposed to substantial strain during the current COVID-19 pandemic (World Health Organization 2019). Overall, female healthcare workers are possibly more likely to develop altered menstrual cycles than other women, and depressive and anxiety symptoms are more common in women with irregular menstruation, with a potential to further impair their quality of life and professional performance as compared with colleagues with regular menstrual cycles (Takmaz Reference Takmaz, Gundogmus and Okten2021).

Current situation in South Asian countries

In high-income countries it has been observed that pubertal age and its association with depressive symptoms might precipitate physical changes in female adolescents (Mendle Reference Mendle, Turkheimer and Emery2007). However, many adolescent females in South Asia are not prone to early reporting of potential premenstrual symptoms, mainly owing to shyness and cultural factors (Hennegan Reference Hennegan, Shannon and Rubli2019). Pre-pandemic challenges for these adolescents (and for many older women as well) regarding their menses are of psychological, social and cultural nature. For example, in some rural areas in low- and middle-income countries, ‘restrictive behaviours’ such as avoiding usual domestic tasks and religious celebrations, concealed washing of reusable menstrual hygiene material/pads, and decreased participation in education, work and community life have been frequently described among adolescent women during their menses (Vashisht Reference Vashisht, Pathak and Agarwalla2018). Additionally, harmful traditions such as socially segregating women during their menses may constrain their ability and desire to participate in community life and put them at risk of not practising basic menstrual hygiene. In some cases, this stems from the cultural belief that menstruating women pollute water supplies and toilets (UNICEF 2020). Other challenges are environmental or financial and may now be exacerbated by the pandemic. Some adolescents avoid events and places lacking sanitary products and safe waste management (Vashisht Reference Vashisht, Pathak and Agarwalla2018). School absenteeism has been significantly associated with the type of sanitary product used, lack of privacy at school, restrictions imposed on girls during menstruation, mothers’ education and sources of information about menstruation issues. In a survey among adolescent female students in Delhi, 65% of respondents acknowledged that their menstrual cycle had an impact on their everyday activities at school. They had to skip important school tests and classes because of distress, fear, guilt and insecurity about staining on their dresses (Vashisht Reference Vashisht, Pathak and Agarwalla2018).

The right to menstrual hygiene, stemming from recognition of women's dignity, is jeopardised by the negligence of public authorities, lack of equitable access to hygiene provisions and safe water, families’ financial struggles during lockdown, and shutdown of dedicated out-patient services for women's healthcare. In India, some of the reported consequences include increased reproductive and urinary tract infections, anaemia, restricted food and liquid intake, gender-based violence and poor mental health (Jahan Reference Jahan2020). It was observed that in Nepal, women with intellectual disability also had difficulty accessing information about menstrual hygiene, which made them feel overwhelmed and isolated; menstrual discomfort was a major challenge that was managed with home remedies; and these women also had to face widespread taboos related to menstruation (Wilbur Reference Wilbur, Kayastha and Mahon2021). Increased domestic responsibilities falling on adolescent girls and women during the pandemic add to the sum of their burdens (Jahan Reference Jahan2020).

Suggestions and proposals

Awareness in adolescence and early adulthood of mental health-related risk factors for menstrual change could decrease prolonged painful bleeding and early menopause (Ansong Reference Ansong, Arhin and Cai2019). There is also a need to identify menstruation-related factors that can be addressed to minimise mental health problems and can be used in the formulation of psychological interventions. Some of these factors are cultural or behavioural, but many are practical.

Cultural and behavioural factors

The role of mass and social media as a means of raising awareness and dispelling ‘myths’ and taboos will help provide accurate information about menstrual and mental health during and after COVID-19 to females of all age groups (UNICEF 2020).

Improvements in behavioural practices could help girls and women maintain menstrual regularity and might contribute to resilience to stress-related disorders, depression and other psychiatric illnesses in both healthcare workers and the general population.

Practical factors

Availability of sanitary pads for all women can only be promoted if adequate good-quality supplies are made accessible and subsidised by the government to make them free of charge (Vashisht Reference Vashisht, Pathak and Agarwalla2018).

Schools and workplaces need to make sanitary products easily available and insist on maintaining menstrual hygiene, which would help minimise excessive absence during menses.

What can healthcare professionals and other agencies do?

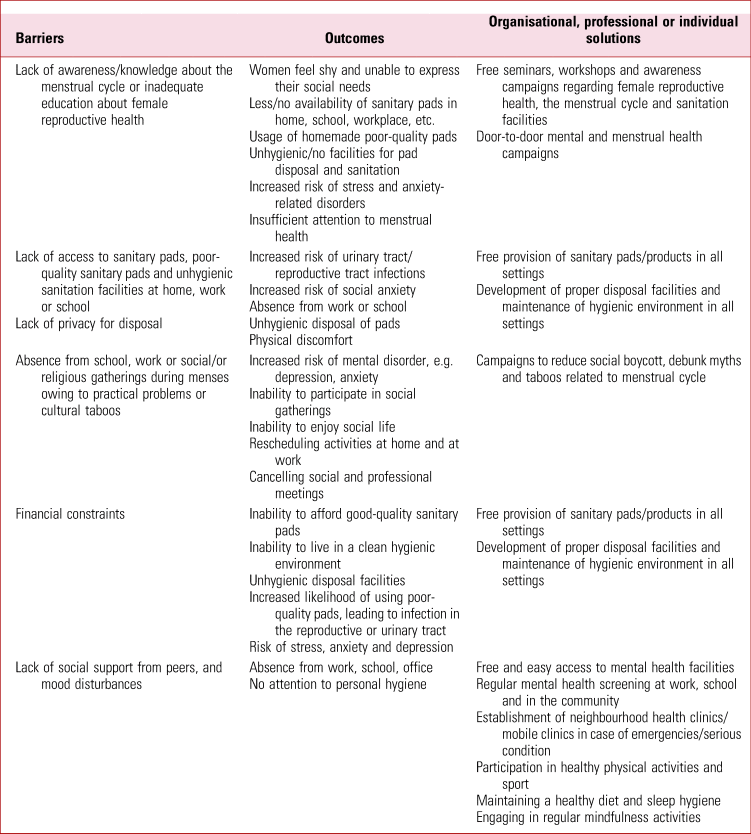

Table 1 outlines five key barriers to menstrual and mental health among women in South Asia. Healthcare workers and clinicians are encouraged to help eliminate some of these barriers by discussing challenges related to menstruation with girls before the age of menarche. They should also teach about the adverse effects on menstruation that prevailing taboos can have.

TABLE 1 Five barriers to menstrual and mental health for women in South Asia and suggestions for addressing them

The barriers and the outcomes of complications and disturbances of menstrual cycle due to psychological impact of COVID-19 are summarized based on these studies: Hennegan (Reference Hennegan, Shannon and Rubli2019), Jahan (Reference Jahan2020), Mendle (Reference Mendle, Turkheimer and Emery2007), Pedrosa (Reference Pedrosa, Bitencourt and Fróes2020), Takmaz (Reference Takmaz, Gundogmus and Okten2021), UNICEF (2020), Vashisht (Reference Vashisht, Pathak and Agarwalla2018) and Wilbur (Reference Wilbur, Kayastha and Mahon2021).

During the current pandemic, physicians should tailor therapy to foster resilience to avoid further complications of the psychological impact of COVID-19 on women's physical and mental health (Vashisht Reference Vashisht, Pathak and Agarwalla2018). ‘Therapy to foster resilience’ emphasises the prevention of the aforementioned complications and disturbances of the menstrual cycle due to the psychological impact of COVID-19 in the following studies: Pedrosa (Reference Pedrosa, Bitencourt and Fróes2020), Takmaz (Reference Takmaz, Gundogmus and Okten2021) and Wilbur (Reference Wilbur, Kayastha and Mahon2021).

Mental health and menstrual hygiene management should be implemented immediately and collectively by multiple agencies and professionals to ensure continuous monitoring of sanitation facilities, waste management, mental health counselling and financial resources to eliminate the risk of both mental illness and COVID-19 infection. Providing hygiene kits and sanitary products to all women in all settings, including detention centres, correctional institutions, domestic violence shelters, health centres, residential care homes and quarantine facilities, will help maintain safety and hygiene during COVID-19. With the help of the media, the introduction of various methods to make reusable menstrual hygiene products widely available and to promote mental health awareness, accompanied by efforts to eradicate period poverty and minimise the risk for development of mental illnesses (UNICEF 2020), would significantly reduce the burden of period poverty, menstrual cycle disorder related to hygiene practices and stress, and associated mental health problems.

Conclusions

Recommendations for all women of reproductive age, including adolescents, housewives, working women and especially healthcare workers, should include adopting a healthy lifestyle and receiving education about the psychological aspects of menstrual cycles. They should be encouraged to consult clinicians without feeling shy or constrained by social taboos and other cultural barriers. Psychotherapy and social support are recommended to reduce the future burden of menstrual cycle irregularities associated with stress, anxiety and depression in women of reproductive age during and after the current pandemic.

Author contributions

All authors agreed on the final version of this article before submitting it.

Funding statement

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Declaration of interest

M.P.d.C. is a member of BJPsych Advances editorial board and did not take part in the review or decision-making process of this article.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.