LEARNING OBJECTIVES

After reading this article you will be able to:

• appreciate the need to explore this poorly understood topic

• describe how personality disorders present in old age

• understand the recommendations for treatment, including non-pharmacological and pharmacological interventions.

There is limited research on personality disorders in adults aged 65 years and older, mostly in the form of reviews, editorials, comments and case reports (van Alphen Reference van Alphen, van Dijk and Videlar2015), owing to an assumption that certain personality disorder types fade out over the lifespan, as reflected by cross-sectional comparisons of older and younger people. However, researchers tend to underestimate the presence of maladaptive traits associated with personality disorders (Gleason Reference Gleason, Weinstein and Balsis2014). Personality disorders can be problematic in older people. Core features, such as disturbed interpersonal relationships and emotional dysregulation, can persist into old age, contributing to a high disease burden, including psychosocial impairment and an elevated suicide risk. Older people with personality disorders are prone to other syndromes, such as anxiety, depression, somatisation and substance dependence disorders (Zweig Reference Zweig, Hillman, Rosowsky, Abrams and Zweig1999). Personality disorders in older people differ in presentation from those seen in younger adults, so it can be difficult to diagnose them (Mattar Reference Mattar and Khan2017). For example, an older person with borderline personality disorder would be likely to use medication non-adherence in order to self-harm rather than self-mutilation (Khasho Reference Khasho, van Alphen and Heijnen-Kohl2019).

Epidemiology: prevalence and course

Studies have generally been methodologically diverse, so it has been difficult to ascertain prevalence estimates of personality disorders in late life. A meta-analysis of 11 studies determined an overall prevalence rate of DSM-III-R personality disorder diagnoses of 10% in adults over 50 years of age, compared with 21% in the under-50 age group (Abrams Reference Abrams and Horowitz1996). Rigorous research is needed to establish prevalence figures, as personality disorders are expected to rise with the ageing population (Beatson Reference Beatson, Broadbear and Sivakumaran2016; Mattar Reference Mattar and Khan2017). Personality disorder diagnoses usually seen in late life include the dependent, obsessive–compulsive, dependent, histrionic, paranoid, schizoid and avoidant types; studies suggest that these diagnoses remain stable over the lifespan or even increase (Gleason Reference Gleason, Weinstein and Balsis2014).

The sparse research on the course of personality disorders across the lifespan could explain why it is difficult to ascertain their onset. Some studies suggest that personality disorders can take four different courses through life. The first course is characterised by a personality disorder starting in early life and having a long duration. In the second course, the disorder no longer meets diagnostic criteria in older age. The third course is identified by temporary remission of symptoms in mid-adulthood, followed by a re-emergence in old age. The fourth course is identified by a disorder emerging in old age that was not evident in early life (Rosowsky Reference Rosowsky, Lodish and Ellison2019).

Why personality disorders are considered to be less prevalent in late life

Research suggests that older adults in prisons and forensic psychiatric hospitals may have been missed out of studies (Mordekar Reference Mordekar and Spence2008). Unhealthy lifestyles and accidents result in shorter life expectancy (van Alphen Reference van Alphen, van Dijk and Videlar2015). Certain personality types may have implications for longitudinal studies; for example, those with poor coping mechanisms are more likely to drop out of research projects. It is also possible that social, financial and physical restrictions have roles in the expression of personality disorders in the elderly; it would be unusual for older people to act out through activities such as sexual promiscuity or drug misuse, in contrast to younger people (Coolidge Reference Coolidge, Burns and Nathan1992). Owing to limited insight into their difficulties, older people with personality disorders often do not seek help (Agronin Reference Agronin and Maletta2000). Stereotyping of older people as rigid or untreatable may cause clinicians to view pathological behaviours as normal for elderly people, leading to underdiagnosis of personality disorders (Agronin Reference Agronin1994). Some studies indicate that borderline personality disorders are less prevalent among older people than among younger people. More research is needed before drawing conclusions about patterns of change in any personality disorder type (Oltmanns Reference Oltmanns and Balsis2011).

Why personality disorders present in late life

In an international Delphi study, experts on personality disorders in older adults reached a consensus on the concept of a ‘late-onset personality disorder’. This concept is consistent with ICD-11 (Rosowsky Reference Rosowsky, Lodish and Ellison2019). The personality pathology may have been contained or hidden by significant others in the person's life, who were able to compensate for the person's difficulties and prevent the personality dysfunction from manifesting itself (Videlar Reference Videlar, Hutsebaut and Schulkens2019). A significant other can serve three functions: buffering – running interference between the individual and others; bolstering – reducing the expression of maladaptive traits by reinforcing adaptive ones; and binding – inhibiting maladaptive behaviours (Box 1). Buffering, bolstering and binding can be provided by roles as well as relationships.

BOX 1 Bolstering, buffering and binding

Buffering

A significant other can buffer or run interference between an individual with a personality disorder and the rest of the world.

For example, a husband instructs his wife with dependent personality disorder in the day-to-day running of the house. Following his death, the wife turns to her elderly sister for support. Her neediness becomes burdensome and overwhelms the sister.

Bolstering

A significant other can bolster or augment the adaptive traits of an individual with a personality disorder, thus reducing the expression of maladaptive traits.

For example, a wife offers her husband with avoidant personality disorder encouragement and support in order to attend family events. Following her death, his personality disorder becomes apparent, to the surprise of his nieces and nephews.

Binding

A significant other can bind or inhibit the maladaptive behaviours of an individual with a personality disorder.

For example, the husband of a woman with borderline personality disorder knows when she is about to have an anger outburst. He is able to prevent the outburst by talking to her about her favourite film or food. Following their divorce after many years of marriage, the wife's relatives take her to the general practitioner for advice because she is struggling to cope with her rages.

Personality disorders can ‘emerge’ in late life following the loss of these significant supporting people, a move into a long-term care placement or loss of a previously stabilising situation such as being in employment (Boxes 2 and 3). The degree of manifestation of a personality disorder often surprises relatives, who were unaware of the function served by the significant other (Segal Reference Segal, Coolidge and Rosowsky2006e). When a person controls their social interactions to avoid aversive feedback, avoidance may reinforce pathology. By repeatedly staying away from interpersonal situations, a person with avoidant personality disorder never learns that they can cope in social situations. In this way, decades of reinforcement without disconfirming feedback function to maintain personality pathology (Morse Reference Morse and Lynch2004).

BOX 2 When bolstering is lost: a personality disorder presenting for the first time in late lifea

Ms X, a 67-year-old woman, was referred to the community mental health team by her general practitioner (GP) for an assessment of her mental health. She was seen by a psychiatrist in the presence of Ms Y, her daughter. Ms X lived alone and Ms Y would visit her four times a week.

Ms Y had been struggling to cope with her mother's behaviour over the past year. Ms X had become irritable. She would have arguments with Ms Y over trivial issues during which she would throw crockery at the wall. She would phone her daughter numerous times during the day, accusing her of not being concerned about her welfare. However, at times, she would suddenly change her view and tell her what a wonderful daughter she was. Ms Y's job would occasionally take her away from home on long business trips, but she frequently had to cancel them because Ms X told her that she felt unwell and needed her daughter to stay with her. The behaviours were deemed to be attention-seeking in nature as Ms Y discovered that her mother was actually in good health. Ms X would frequently ask the GP for opiates to relieve back pain, which Ms Y did not think were needed. Attempts made by Ms Y to challenge her mother about her behaviours or reduce the frequency of visits would be met with hostility and threats of self-harm.

The psychiatrist, on further interviewing, discovered that Ms X's problems had developed following retirement. She had worked as a nurse from a young age with enthusiasm and passion. Following retirement, she had been devastated, saying that she did not know what to do with herself. Ms Y confirmed that there had been no concerns over her mother's behaviour prior to retirement. On being asked about her childhood history, Ms X said that she had been raised by a single mother and had never known her father. She had loved her mother but had never felt able to discuss any worries with her.

The psychiatrist gave Ms X a diagnosis of borderline personality disorder. He explained how her job had helped in bolstering (potentiating and reinforcing) the more adaptive behaviours, thereby reducing the expression of maladaptive traits. The personality disorder had become apparent following retirement as her job was no longer supporting her in bringing out her best. He discussed her case with the multidisciplinary team. Since her job had helped in containing the personality disorder for so long, the team suggested that she worked in a different capacity, such as teaching nursing students. Ms X eventually went back to nursing part-time. On the days she was not working as a nurse, she volunteered in a charity shop. Six months later, Ms Y reported that her mother was more settled and that their relationship had improved.

aThe case vignettes in Boxes 2 and 3 are both fictitious.

BOX 3 The loss of buffering and binding: a personality disorder re-emerging in later life

Ms B was raised by her father, her mother having died in childbirth. The family moved house several times during her childhood because of his job in the army. Ms B regularly took part in school plays, as she was good at singing and acting. She married Mr B at age 19. By her late teens, she was already working in films and theatre productions. Mr B often found her preoccupied with fantasies of stardom. She would expect others to recognise her for being a world-famous actress who had worked in the highest-grossing movies. Mr B discovered that things were not as glamourous as they seemed. Film directors were reluctant to give Ms B roles owing to her ‘difficult’ nature. She required excessive admiration from others and on several occasions considered herself to be better than fellow actors, refusing to work with them. She took little interest in her marriage, telling Mr B that she had more important things to do. At times, she would tell him that he was envious of her good fortune and higher social status. During her 30s, he took her to a general practitioner (GP) as there was ‘something not quite right about her’ and asked if there was any help she could receive. The GP felt that she had a narcissistic personality and suggested that he refer her to a psychiatrist for further assessments. She refused, saying that she doubted whether any psychiatrist would be qualified enough to assess her.

A frustrated Mr B decided to help Ms B by becoming her film agent and serving the purpose of buffering (becoming a go-between) to minimise her contacts with others. Between her 40s and 60s, she had supporting roles in two television series that ran for several years. They gave her a sense of fulfilment and the relationship with her husband improved. During her late 60s, osteoarthritis severely affected her mobility and Mr B had to provide assistance in her daily self-care. At the age of 69, she was admitted to a residential care home as Mr B developed heart problems that left him no longer able to care for her. The care home staff struggled to care for Ms B. She demanded to be seen only by senior staff members and would become angry if she felt that they were giving other residents more attention than she was receiving. She found fault with all aspects of her care and would file complaints about the staff on a daily basis. She said that the staff should suffer from arthritis in order to understand her situation and thus provide better care.

Ms B's GP had retired and her new GP referred her to the community mental health team (CMHT) in order that the care home staff receive support in managing her care. The GP informed the CMHT psychiatrist that her retired colleague had suggested further assessments for a narcissistic personality. The psychiatrist assessed Ms B and took a collateral history from Mr B. She diagnosed Ms B with a narcissistic personality disorder. She felt that Mr B's buffering role and Ms B's acting in long-running television shows had helped to convert the dysfunctional behaviours into less maladaptive traits during midlife. The CMHT psychiatrist and care coordinator encouraged participation in music therapy and activities involving play-acting. They suggested that the staff members spend time with Ms B, discussing her acting experiences and also watching her television roles with her. Such activities enabled her to feel admired and valued. Ms B became more settled over time and her relationship with the care home staff improved.

Clinical presentations of personality disorders in late life

The literature on how personality disorders present in later life is based on limited studies undertaken by researchers and the clinical experiences of clinicians. Longitudinal studies would provide an understanding of the course of personality disorders into late life, but they have mainly focused on younger people (Videlar Reference Videlar, Hutsebaut and Schulkens2019). It may be best to study personality disorders during periods of significant transition, because the enduring behavioural and affective expressions that define the individual will be amplified at such times (Oltmanns Reference Oltmanns and Balsis2011).

Paranoid personality disorder

A history obtained from someone who has known the person for a long time may help to ascertain whether they have a paranoid personality disorder, a psychotic illness or dementia. The paranoia of a delusional disorder tends to be fixed, severe and resistant to treatment. The paranoia of schizophrenia tends to be bizarre or fragmented and is often associated with hallucinations. In contrast to a dementing process, a paranoid personality disorder is generally associated with an earlier age of onset; the paranoia heightens when the individual has to change location or rely on strangers for help. On admission to long-term care settings, patients may file complaints against staff for holding them against their will (Agronin Reference Agronin, Rosowsky, Abrams and Zweig1999). Paranoia also tends to become more pronounced when experiencing sensory impairment (Segal Reference Segal, Coolidge and Rosowsky2006a).

Schizoid personality disorder

Individuals with schizoid personality disorder can become more eccentric, withdrawn and anxious in late life (Agronin Reference Agronin, Rosowsky, Abrams and Zweig1999). They prefer to be alone and independent, thus they struggle to adjust to hospitals or long-term care settings as they feel threatened by what they deem to be constant intrusions by staff. Sharing rooms with others can be a painful experience for them. They therefore aim to leave hospital quickly. They may even value the enhanced social isolation brought about by limited mobility and resources (Agronin Reference Agronin1994; Reference Agronin, Rosowsky, Abrams and Zweig1999).

Losing a significant other owing to bereavement is not particularly stressful because the attachment to this person was probably less intense compared with that of other adults without the disorder. Grief over the loss of the significant other would probably be related to practical factors such as the loss of having someone to do the housework rather than the loss of an emotional attachment (Segal Reference Segal, Coolidge and Rosowsky2006a).

Schizotypal personality disorder

Studies suggest that schizotypal personality disorder either remains the same or worsens in later life (AgroninReference Agronin1994). Social isolation related to eccentricities and odd beliefs can become more pronounced over time. Individuals can come across as being unkempt, wearing inappropriate clothing and living in squalid conditions. They tend to experience social anxiety and can be suspicious of others. Institutionalisation can be devastating for them as they have no choice but to face multiple social interactions (Segal Reference Segal, Coolidge and Rosowsky2006a).

Antisocial/dissocial personality disorder

A follow-up study of men with antisocial personality disorder into late life showed that, although most were no longer having frequent confrontations with the police, they continued to have poor occupational performance, social isolation and marital discord (Black Reference Black, Baumgard and Bell1995).

Aggressive and reckless behaviours may decrease as the person's stamina declines with age. Empathy rarely develops over time. Those who reach late life have poor social support owing to rejection by others on account of their manipulative behaviours (Segal Reference Segal, Coolidge and Rosowsky2006b). Disruptive behaviours such as belligerence, assaultiveness, stealing and surreptitious substance misuse can be seen in care home settings. These people often tend to leave the care home without authorisation, thus putting themselves in dangerous situations (Agronin Reference Agronin, Rosowsky, Abrams and Zweig1999).

Borderline personality disorder

Long-term follow-up studies of older people with borderline personality disorder have not yet been performed (Videlar Reference Videlar, Hutsebaut and Schulkens2019). Studies in younger people show that remissions are common and recurrences are rare. Remitted individuals show a slow but steady improvement in psychosocial functioning over time (Paris Reference Paris, Brown and Nowlis1987; McGlashan Reference McGlashan, Grilo and Skodol2000; Stone Reference Stone2016).

Non-recovered individuals experience higher rates of vocational impairment and physical morbidity than recovered individuals. In contrast to individuals with other personality disorder types, those with borderline personality disorder belatedly achieve the milestones of young adulthood (Zanarini Reference Zanarini, Frankenburg and Hennen2005; Stone Reference Stone2016). Many enter late life without enough social support. They often lack the skills to replace these losses and manipulative, self-destructive and disruptive behaviours can result (Agronin Reference Agronin1994).

The cognitive stigmata of the disorder, i.e. identity diffusion, can be seen as an inability to formulate plans for the future or pursue goal-directed activities (Agronin Reference Agronin1994). Self-injury in earlier life is not only difficult to hide but may also elicit negative feedback, which may slowly shape these behaviours out of the person's repertoire over time (Morse Reference Morse and Lynch2004). Instead, there may be geriatric versions of self-harming behaviours such as anorexia nervosa or sabotage of medical treatment (Agronin Reference Agronin1994).

Symptoms that can persist with age are emotional instability, feelings of emptiness and dysfunctional interpersonal relationships that generate chaotic environments in the home. Somatisation is common and is often expressed in dramatic demands for medical attention. Treatments arising from somatisation can lead to prolonged hospital admissions (Valdivieso-Jiménez Reference Valdivieso-Jiménez2018). Splitting, i.e. the tendency for patients to become attached to particular team members, segregating them from others whom they believe to be less able, is common. Patients' preferences may change abruptly, which can confuse staff. They can evoke negative countertransference reactions (feelings and behaviours evoked in the clinician by the patient). Many people with borderline personality disorder have worn out families during a lifetime of crises and poor boundaries (Agronin Reference Agronin, Rosowsky, Abrams and Zweig1999; Segal Reference Segal, Coolidge and Rosowsky2006b).

There have been strong suggestions of a history of childhood trauma as a precipitating event for the development of this disorder. However, not all people with borderline personality disorder have a history of trauma and not all individuals with a history of trauma develop the disorder. Borderline personality disorder is also considered to have a genetic component (Segal Reference Segal, Coolidge and Rosowsky2006b).

Histrionic personality disorder

People with histrionic personality disorder tend to overestimate their physical attractiveness and, in their quest for youthfulness, can become reliant on cosmetic surgery and other anti-ageing techniques. They can initially come across as warm and entertaining, but their self-centredness is eventually discovered, leading to negative responses from others. They are devastated by the reduction in their sex appeal as they age. Because seductiveness has been part of their social style for so long, they struggle to relate to others without trying to attract them. Consequently, they are likely to draw attention to themselves through somatic and hypochondriacal complaints rather than with their usual physical charms. Core features such as arrogance, need for admiration and limited capacity for empathy generally do not improve with age. Owing to their manipulation of others they tend to be alienated from family members (Agronin Reference Agronin, Rosowsky, Abrams and Zweig1999; Segal Reference Segal, Coolidge and Rosowsky2006b).

Narcissistic personality disorder

A long-term follow-up study of people with narcissistic personality disorder showed poor social functioning over time (Plakun Reference Plakun1989). Research indicates that the majority do not improve in late life. In reaction to feeling powerless, there will be greater demands for admiration, which are often disregarded by others. Many with the disorder feel that needing help and support from others lowers their social status. Research suggests that some individuals may become more interested in therapy as their charming personalities becoming less rewarding. As their power over others declines, they may seek power through relationships with their therapist (Segal Reference Mordekar and Spence2006b). However, these individuals can repeatedly ask questions or have demands that derail therapy (Agronin Reference Agronin, Rosowsky, Abrams and Zweig1999).

Avoidant/anxious personality disorder

Research suggests that people with avoidant/anxious personality disorder experience shyness and social anxiety that becomes more pronounced with age (Agronin Reference Agronin, Rosowsky, Abrams and Zweig1999). They are vulnerable to social losses as they have great difficulty in replacing relationships that are lost. They generally do not apply for supportive services owing to fear of being evaluated and found wanting. Individuals can demonstrate marked fearfulness, which can be particularly problematic in hospitals or long-term care settings (Segal Reference Segal, Coolidge and Rosowsky2006c).

Dependent personality disorder

Problems can arise for older people with dependent personality disorder when their significant others die, leaving them to depend on themselves. In such situations, they often turn to their children for support. Their neediness becomes burdensome and the children become overwhelmed. In contrast to other personality disorder types, these people are likely to seek out supportive services. Differentiating between those who are dependent on others due to unfortunate life circumstances and those whose dependence is excessive in their current situation is important (Agronin Reference Agronin, Rosowsky, Abrams and Zweig1999; Segal Reference Segal, Coolidge and Rosowsky2006c).

Obsessive–compulsive/anankastic personality disorder

In later life, people with obsessive–compulsive/anankastic personality disorder tend to become more obsessive and anxious in response to losses, especially those related to control and predictability (Agronin Reference Agronin, Rosowsky, Abrams and Zweig1999). Symptoms of this disorder may be exacerbated by changes in routine and environment (such as a move into long-term care), which disrupt the person's sense of control (Agronin Reference Agronin1994). Increased dependency on others can be stressful for these people. Their deep-rooted pattern of doing things their own way makes them resistant to change. They find it hard to be flexible when experiencing impaired physical function. They are offended when offered help, which they misinterpret as not being in control of their lives (Segal Reference Segal, Coolidge and Rosowsky2006c).

Personality disorders and mood disorders in later life

The prevalence of personality disorders in elderly people with depression may be as high as 24% (Courtois Reference Courtois, Enfoux and Coutard2014). A personality disorder should be a differential diagnosis in an older patient with depression who fails to respond to treatment, including psychotherapy. Although infrequent, suicide attempts by elderly people with personality disorders tend to be life-threatening (Beatson Reference Beatson, Broadbear and Sivakumaran2016). When anxiety is a prominent feature in an elderly person it may be a strong pathognomonic sign for the presence of a personality disorder such as the schizotypal, dependent, avoidant, obsessive–compulsive or schizoid type (Coolidge Reference Coolidge, Segal and Hook2000).

When personality changes are not due to a personality disorder

It can be difficult to ascertain whether the clinical picture is a result of an underlying personality disorder, a difficult doctor–patient relationship, neurocognitive impairment, a medical condition (Box 4) or medication (Table 1). One should also consider cultural roles, eccentricities, situation-specific behaviours and the physiological effects and environmental aspects of ageing (Zweig Reference Zweig, Hillman, Rosowsky, Abrams and Zweig1999; Mattar Reference Mattar and Khan2017).

TABLE 1 Medications that can cause personality changes

BOX 4 Medical conditions that can cause personality changes

• Pernicious anaemia

• Head trauma

• Environmental toxicants (lead, cadmium, mercury, ethanol)

• Brain tumours and space-occupying lesions in the brain

• Dementia

• Cerebrovascular events

• Huntington's disease

• Epilepsy

• Systemic lupus erythematosus

• Endocrine problems (hypothyroidism, hypoadrenocorticism, hyperadrenocorticism)

• Infections (meningitis, encephalitis)

• Poorly controlled chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

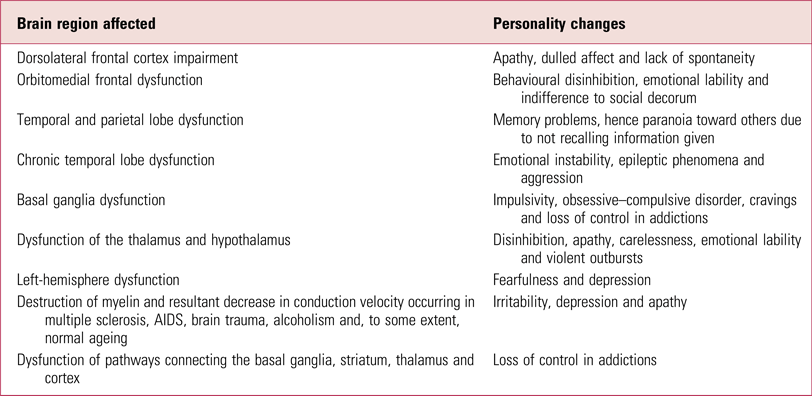

Personality changes can also be due to brain dysfunction (Table 2). For example, the frontal lobe impairment caused by Alzheimer's disease, frontotemporal dementia, cerebral atrophy of normal ageing and strokes can result in personality changes. Parkinson's disease and thyroid problems can cause symptoms mimicking frontal lobe damage. Space-occupying lesions in the brain can lead to depression, anxiety, emotional lability, indifference and apathy. Subdural haematomas can cause depression and lethargy. Brain metastases can cause depression, anxiety and paranoia. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease can cause irascibility and impatience. Frontotemporal dementia, mania, stroke, head injury and impulse control disorders can cause antisocial behaviours (Miner Reference Miner, Rosowsky, Abrams and Zweig1999).

TABLE 2 Personality changes caused by brain dysfunction

Normal ageing of the brain does not greatly alter one's personality, but organic brain disease does. Personality changes can occur as a result of dementia-related organic changes, but they can also occur as a reaction to dementia itself. In an individual with a subthreshold personality disorder, a dementia can also unleash underlying behavioural tendencies that the person was able to control when well (Mordekar Reference Mordekar and Spence2008). When an individual with an established personality disorder develops a dementia, the effect can be to increase the degree of the personality disorder, to decrease it or to neutralise (or cancel) it. In general, dementia induces an increase in self-centredness and a decrease in flexibility (Segal Reference Segal, Coolidge and Rosowsky2006d).

Assessment and diagnosis

An assessment depends on acquiring an accurate lifetime history. This can present its own challenges when the reports of patients and informants are influenced by cognitive impairment and stigma attached to socially undesirable behaviours (Abrams Reference Abrams and Bromberg2007). Clinicians can experience difficulty in distinguishing between long-standing personality dysfunction and recent reactive personality changes (Agronin Reference Agronin and Maletta2000).

The personality pathology is often noticeable during an encounter with the patient. For example, people with schizotypal personality disorder can be identified by their unusual language and manner of dressing. The social impairment associated with a personality disorder can become apparent after asking the patient to describe relationships with significant others, friends and family over time. It is useful to ask whether the emotional symptoms developed or worsened after specific social stressors (Segal Reference Segal, Coolidge and Rosowsky2006e; Balsis Reference Balsis, Zweig, Molinari, Lichtenberg and Mast2015).

Personality disorder symptoms can ebb and flow over time and may be exacerbated or dampened in the presence of certain people. Therefore assessments in multiple contexts and across different occasions are vital. Individuals who have regular contact with the patient offer a unique perspective as they are able to shed light on lifelong patterns of behaviour. Such informants can include relatives but also teams (doctors, nurses, occupational therapists, social workers, support workers and healthcare assistants) working in care homes, wards and community mental health settings. Behavioural charts and records may provide clues to personality disorder features, especially if the same traits are seen by different professionals (Segal Reference Segal, Coolidge and Rosowsky2006e).

Diagnostic criteria and tools

The DSM and ICD are used to make a diagnosis of a personality disorder.

DSM-5 (American Psychiatric Association 2013) largely retains the old DSM-IV classification for personality disorders (American Psychiatric Association 1994), with its corresponding categories. A dimensional approach was initially recommended for DSM-5, in view of the diagnostic heterogeneity within categories. It was approved by the DSM-5 Task Force but not by the American Psychiatric Association Board of Trustees, who felt that it needed more study. Eventually it was included in DSM-5 only as an alternative model for personality disorders, in section III ‘Emerging measures and models’ (Oltmanns Reference Oltmanns and Widiger2018).

There were problems with the ICD-10 classification (World Health Organization 1992) of ten personality disorders, in that the borderline and dissocial types were being recorded more frequently than the others. Moreover, most individuals with severe disorders met the requirements for multiple personality disorders (Reed Reference Reed, First and Kogan2019). The ICD-11 classification (World Health Organization 2018), which comes into effect in January 2022, addresses these issues by using a dimensional approach. First, the clinician has to identify the presence of a personality disorder. The severity (mild, moderate or severe) of the disorder can then be ascertained depending on the dysfunction in interpersonal relationships and everyday life of the patient. If deemed appropriate, one or more prominent trait qualifiers (negative affectivity, detachment, disinhibition, dissociality and anankastia) that contribute to the expression of personality dysfunction can be identified (Bach Reference Bach and First2018). An optional qualifier is provided for ‘borderline pattern’, which was added to ensure continued recognition of borderline personality disorder, which has been of most use and interest to clinicians (Oltmanns Reference Oltmanns and Widiger2019). Determining severity and trait qualifiers could determine the intensity and focus of treatment; research is needed to explore the clinical utility of ICD-11. The estimation of severity focuses on harm to self or others (Bach Reference Bach and First2018). Older adults with severe personality disorders, in contrast to younger people, tend to undergo diet restriction or medication misuse rather than self-mutilation (Agronin Reference Agronin1994; Beatson Reference Beatson, Broadbear and Sivakumaran2016). In contrast to the DSM-5 dimensional approach, the ICD-11 dimensional trait model has not been well-researched (Oltmanns Reference Oltmanns and Widiger2018).

The DSM-5 criteria may not help in diagnosing personality disorders in the elderly (Mattar Reference Mattar and Khan2017; Rosowsky Reference Rosowsky, Lodish and Ellison2019) as they were created with younger patients in mind. They fail to take into account normal changes associated with ageing and personality disorders presenting differently in later life. For example, borderline personality disorder criteria may be problematic for older adults: it would make sense for them to avoid abandonment, as they are dependent on others for support to meet their care needs (Segal Reference Segal, Coolidge and Rosowsky2006b; Khasho Reference Khasho, van Alphen and Heijnen-Kohl2019). Some evidence suggests that the alternative dimensional approach in DSM-5 is age-neutral (Videlar Reference Videlar, Hutsebaut and Schulkens2019).

The Gerontological Personality Disorders Scale is a 16-item screening tool validated for older adult out-patients. It broadly screens for personality disorders but does not measure any personality disorder in particular (Oltmanns Reference Oltmanns and Balsis2011). It is not widely used (Balsis Reference Balsis, Zweig, Molinari, Lichtenberg and Mast2015; Mattar Reference Mattar and Khan2017). Diagnostic tools are generally not considered suitable for older people as they are in the form of lengthy structured interviews that rely on the self-reporting of behaviours, which can be overwhelming for this age group (Zagaria Reference Zagaria2014; Beatson Reference Beatson, Broadbear and Sivakumaran2016).

Diagnosis by clinical consensus

Ideally, the last step in reaching a diagnosis is for clinicians to hold a conference to finalise the diagnosis by consensus. The clinicians bring their respective data and impressions to the meeting. They should be familiar with the individual's level of functioning in different settings and over an extended period. This would help rule out other functional mental illnesses. Clinicians should have adequate knowledge of the latest diagnostic criteria. The diagnosis would be practical and valid from a clinical point of view. Through discussions, a case formulation could be developed to explain the dynamics underlying the patient's presentation. However, clinical consensus has not been defined in most studies. Moreover, the literature does not discuss tests of reliability (Agronin Reference Agronin and Maletta2000).

Management

Researchers have not delved deeply into the management of late-life personality disorders, so there is limited knowledge on treatment outcomes (Mattar Reference Mattar and Khan2017; Videlar Reference Videlar, Hutsebaut and Schulkens2019).

Psychosocial interventions

In long-term care settings or hospitals, older people with personality disorders can create conflicts with staff over their care. The rules and procedures of the mental health setting, expectations regarding the speed of replying to non-emergency telephone calls and other limits should be explained at the initiation of the clinician–patient relationship. Patients should understand that rules apply to all patients and should be seen not as a punishment but for the patients' protection (Abrams Reference Abrams and Bromberg2007).

In the case of patients with borderline personality disorder, it is advised to employ a coordinated team approach to prevent splitting. Clinicians should use countertransference to understand the patient and respond in ways to advance the therapeutic relationship and reduce stress. It is poor clinical practice to believe that older people's behaviours should be tolerated more than younger people's behaviours. Clinicians should adhere to boundaries to maintain a therapeutic framework in which progress can be achieved. The team should regularly review the short- and long-term goals to ensure consistency in their relationship with the patient (Balsis Reference Balsis, Zweig, Molinari, Lichtenberg and Mast2015). Staff anger should be vented in staff meetings rather than at the patient. Otherwise, it might be reinforcing for the patient to see staff act out their feelings of rage. Suicidal or self-injurious behaviours should be treated with compassion but with firm limit-setting. Enhancing positive traits reduces the expressions of less desirable traits and increases the probability that the individual will receive positive feedback from the environment (Agronin Reference Agronin, Rosowsky, Abrams and Zweig1999).

Non-adherence to treatment is common in people with antisocial personality disorder. Staff should manage this by arranging a meeting with a person of authority, such as the care home manager. Individuals with antisocial personality disorder have difficulty in forming meaningful relationships with others and it will therefore be difficult to establish a collaborative working relationship. Instead of helping these patients to develop empathy for others, it might be more useful to help them think through the consequences of their actions and discover strategies to stay out of trouble. Clinicians provide warm, supportive environments to all their patients, however they may need to deviate from this practice when managing patients with schizoid personality disorders. These patients would prefer to keep all interactions to a minimum and do not want praise or encouragement (Segal Reference Segal, Coolidge and Rosowsky2006a).

People with anankastic traits prefer precise routines for scheduling treatment schedules. It can be difficult for clinicians to adjust their schedules to meet their needs. They should instead focus the energies of these individuals on tasks in which they have a sense of control.

Professionals may become overwhelmed by the attentional needs and dramatic expressiveness of an individual with histrionic personality disorder, who could benefit from participation in group activities which can provide attention and constructive feedback.

The maladaptive attempts of someone with a narcissistic personality to cope with losses of attractiveness and physical function may include hostility and controlling behaviours. It is important to identify the losses that are devastating to the patient. Supportive interactions will help bolster their need for admiration.

In paranoid personality disorder, individuals would benefit from a straightforward and consistent approach to management. A solicitous or challenging approach could be misinterpreted as threatening, leading to hostility and accusations.

Professionals may need to endure the peculiarities of individuals with schizotypal personality disorder unless they are leading to behaviours that pose a risk of danger to the patient or others.

It is vital to identify losses and fears that cause avoidant behaviours. Someone who avoids social situations because of incontinence can be treated with medications, exercises and protective undergarments.

Health professionals can struggle to cope with the excessive questions and neediness of a patient with dependent personality disorder. Failure to obtain enough nurturance can lead to clinging behaviours and frequent somatic complaints. This can be overcome by scheduling brief, regular and supportive contact. Clinicians should explain limits in their ability to provide care while also conveying their willingness to help (Agronin Reference Agronin, Rosowsky, Abrams and Zweig1999).

Specific psychotherapies

Some researchers feel that cognitive–behavioural therapy (CBT) and dialectical behavioural therapy (DBT) may be useful in older people with personality disorders. CBT, for example, could be used to identify individuals’ strengths and use them to effect positive change. However, there is no consensus regarding such psychological treatments, owing to limited research (including controlled studies) in older people (Balsis Reference Balsis, Zweig, Molinari, Lichtenberg and Mast2015; Mattar Reference Mattar and Khan2017). The first trial of schema therapy (multiple baseline case series design) for borderline personality disorder in older adults is currently being conducted (Khasho Reference Khasho, van Alphen and Heijnen-Kohl2019).

Pharmacological interventions

Pharmacological treatments can be used for those with little motivation to change and self-reflect or those who exhibit risky behaviours (Balsis Reference Balsis, Zweig, Molinari, Lichtenberg and Mast2015). The prescriber must take time to discuss the purpose of medications in an open manner. The judicious use of the fewest agents is preferred and the use of as-needed (‘p.r.n.’) medications should be discouraged; such schedules often play into maladaptive needs for dependency and control (Agronin Reference Agronin, Rosowsky, Abrams and Zweig1999).

Impairment of cognitive/perceptual organisation

Cognitive/perceptual impairment can lead to discomfort in social interactions and misunderstanding or suspicion of others' motivations. These psychosis-like symptoms can be seen in personality disorders such as the schizotypal type and are similar to symptoms seen in schizophrenia. Studies have shown impaired brain dopaminergic activity in both types of condition. Antipsychotics, by reducing dopaminergic activity, help improve psychosis-like symptoms (Siever Reference Siever and Davis1991; Zagaria Reference Zagaria2014).

Impulsivity and aggression

Personality disorders present with impulsivity and aggression in various ways. Individuals with antisocial personality disorder tend to steal or tell lies. Those with borderline personality disorder can get involved in substance misuse. Impulsivity and aggression can be due to impaired serotonergic and noradrenergic systems that mediate behavioural inhibition. Lithium, which enhances serotonergic activity, can help reduce aggression. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) can reduce impulsive behaviours (Zagaria Reference Zagaria2014). Antidepressants, by enhancing noradrenergic activity, can reduce impulsivity and aggression. Anti-adrenergic agents such as propranolol can improve aggressive behaviours (Siever Reference Siever and Davis1991).

Affective instability

Hyper-responsiveness of the noradrenergic system, in contrast to the reduced responsiveness seen in the classic affective disorders, may cause affective instability in borderline personality disorder. Mood stabilisers such as lithium and carbamazepine may be able to steady catecholamine activity, thus stabilising mood (Siever Reference Siever and Davis1991; Zagaria Reference Zagaria2014).

Anxiety and inhibition

In some personality disorders, such the avoidant/anxious type, the anxious individual interprets environmental events as threatening. When this person acts, it is often in the direction of avoidance of or withdrawal from the environment. The underlying cause is not clear, but research suggests that other anxiety disorders may be linked to impaired noradrenergic and GABAergic activity (Siever Reference Siever and Davis1991). Agents that mediate gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) activity, such as pregabalin and benzodiazepines, can be used. Benzodiazepines are used with caution because of their addiction potential. SSRIs, by enhancing noradrenergic activity, can also be used.

Conclusions

With the rise in the elderly population, there will be greater numbers of people struggling with personality disorders, resulting in an increased burden of the disorder on health services (Beatson Reference Beatson, Broadbear and Sivakumaran2016). The situation is not entirely grim; a number of older people with personality disorders show more effective coping than their younger counterparts, indicating that experience and wisdom acquired with age may result in healthier coping responses in spite of potentially greater exposure to losses and stressors (Coolidge Reference Coolidge, Segal and Hook2000). Temperaments that shape personality disorders are unlikely to be dramatically changed, but their expression can sometimes be reformed in ways that are less troubling for patients and families (Segal Reference Segal, Coolidge and Rosowsky2006d). The timely identification of these patients is urgently needed so that they can receive the support required to alleviate their suffering in later life.

MCQs

Select the single best option for each question stem

1 Regarding the ICD-11 diagnostic criteria for personality disorders:

a the ICD-11 classification goes into effect in January 2021.

b the estimation of severity of a personality disorder does not focus on harm to self or others.

c the ICD-11 uses a dimensional approach.

d the severity (mild or severe) of the personality disorder can be ascertained.

e an optional qualifier is not provided for ‘borderline pattern’.

2 Regarding the DSM-5 diagnostic criteria for personality disorders:

a people with obsessive–compulsive personality disorder are able to focus on both work and leisure activities.

b people with dependent personality disorder are able to make decisions for themselves without depending on others.

c people with paranoid personality disorder perceive attacks on their reputations that are not apparent to others.

d people with avoidant personality disorder are able to manage social situations without worrying over whether they will be criticised.

e people with borderline personality disorder do not have feelings of emptiness.

3 Regarding medical conditions and associated personality changes:

a antisocial behaviours cannot be a consequence of strokes.

b space-occupying lesions in the brain cannot cause emotional lability.

c thalamic disorders do not affect personality.

d subdural haematomas can cause lethargy.

e thyroid disease cannot affect personality.

4 Regarding the management of late-life personality disorders:

a negative affectivity, detachment, inhibition, dissociality and anankastia are used by ICD-11 to describe personality dysfunction.

b clinicians holding a conference to reach a diagnosis by consensus would be helpful.

c a coordinated team approach would not help in managing individuals with personality disorders.

d assessing the patient in multiple contexts would not be helpful in diagnosing a personality disorder.

e personality pathology cannot be identified from a patient's appearance.

5 Regarding the presentation of personality disorders in late life:

a when anxiety is a prominent feature in an elderly person it may be a pathognomonic feature of an antisocial personality disorder.

b people with avoidant personality disorder experience social anxiety.

c people with narcissistic personality disorder are able to handle losses in physical function.

d people with paranoid personality disorder are generally happy to accept help from health professionals.

e people with schizoid personality disorder prefer to be less isolated in old age.

MCQ answers

1 c 2 c 3 d 4 b 5 b

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.