Introduction

Constraint-induced movement therapy (CIMT) is an effective intervention for reducing arm impairment and improving arm function after stroke (Corbetta, Sirtori, Castellini, Mjoa, & Gatti, Reference Corbetta, Sirtori, Castellini, Mjoa and Gatti2015; Kwakkel, Veerbeek, van Wegen & Wolf, Reference Kwakkel, Veerbeek, van Wegen and Wolf2015) and traumatic brain injury (TBI) (Shaw et al., Reference Shaw, Morris, Uswatte, McKay, Meythaler and Taub2005). While protocols vary, key components of a CIMT programme include (1) completion of a high-intensity, task-orientated rehabilitation programme with the affected arm, often for several hours per day for two to three weeks; (2) wearing a mitt restraint (for up to 90% of waking hours) on the non-affected arm to encourage use of the more-affected arm outside of structured therapy and (3) the use of a transfer package focused on participant behaviour change, to support generalisation of skills acquired during therapy into daily life (Corbetta et al., Reference Corbetta, Sirtori, Castellini, Mjoa and Gatti2015). CIMT remains under-utilised by therapists despite strong evidence of CIMT effectiveness (Corbetta et al., Reference Corbetta, Sirtori, Castellini, Mjoa and Gatti2015) and its inclusion as a strong recommendation in the Australian Clinical Guidelines for Stroke Management (Stroke Foundation, 2021). While therapists’ perceptions of the barriers to CIMT delivery that contribute to this under-utilisation, such as lack of knowledge, resources and concerns about patients’ suitability for a programme, have been explored (Eigbogba, Pedlow & Lennon, Reference Eigbogba, Pedlow and Lennon2010; Fleet et al., Reference Fleet, Che, MacKay-Lyons, MacKenzie, Page, Eskes and Boe2014; Pedlow, Lennon & Wilson, Reference Pedlow, Lennon and Wilson2014), little is known about the opinions and experiences of CIMT consumers, including those who have successfully completed a CIMT programme.

What makes matters complex when exploring the willingness of patients to participate in CIMT, is that there are many different high quality, evidence-based CIMT protocols of varying intensity (Barzel et al., Reference Barzel, Ketels, Stark, Tetzlaff, Daubmann, Wegscheider and Scherer2015; Doussoulin, Rivas, Rivas & Saiz, Reference Doussoulin, Rivas, Rivas and Saiz2018; Kwakkel et al., Reference Kwakkel, Winters, van Wegen, Nijland, van Kuijk, Visser-Meily and Meskers2016; Lin, Wu, Liu, Chen & Hsu, Reference Lin, Wu, Liu, Chen and Hsu2009). Additionally, CIMT has been found to be effective for stroke and TBI survivors in the acute, sub-acute and chronic phases (Kwakkel et al., Reference Kwakkel, Winters, van Wegen, Nijland, van Kuijk, Visser-Meily and Meskers2016; Shaw et al., Reference Shaw, Morris, Uswatte, McKay, Meythaler and Taub2005; Thrane et al., Reference Thrane, Askim, Stock, Indredavik, Gjone, Erichsen and Anke2015; Wolf et al., Reference Wolf, Thompson, Winstein, Miller, Blanton, Nichols-Larsen and Sawaki2010, Reference Wolf, Winstein, Miller, Taub, Uswatte and Morris2006). The experiences and opinions of CIMT consumers may differ depending on these programme and patient factors. Furthermore, in the literature, only stroke survivors’ opinions of CIMT programmes have been published.

The largest study of participant perceptions of CIMT asked 208 stroke survivors to complete a self-report questionnaire (Page, Levine, Sisto, Bond & Johnston, Reference Page, Levine, Sisto, Bond and Johnston2002). Most respondents had not completed CIMT and were simply asked for their opinions on a written description of the original CIMT protocol (i.e. CIMT for six hours per day over two weeks, wearing a mitt restraint for up to 90% of waking hours, and the transfer package) and a summary of the evidence for CIMT effectiveness. Over two-thirds of respondents (n = 143, 68%) were not interested in participating in CIMT because of the number of hours of therapy per day, the number of therapy days and the mitt-wearing regime (Page et al., Reference Page, Levine, Sisto, Bond and Johnston2002). Since this study, findings from two qualitative studies have indicated that participants perceived improvements in their arm function and use in daily life after receiving CIMT in the context of a clinical trial but identified a number of challenges during their programme (Borch, Thrane & Thornquist, Reference Borch, Thrane and Thornquist2015; Stark, Färber, Tetzlaff, Scherer & Barzel, Reference Stark, Färber, Tetzlaff, Scherer and Barzel2019). In the Norwegian Constraint-Induced (CI) Therapy Multisite Trial (NORCIMT) (Stock et al., Reference Stock, Thrane, Askim, Karlsen, Langørgen, Erichsen, Gjone and Anke2015), three acute stroke survivors (within 28 days post-stroke) who had completed CIMT were interviewed (Borch et al., Reference Borch, Thrane and Thornquist2015). This trial involved three hours of CIMT per day, for 10 days with a therapist, and included mitt wear and the transfer package. Challenges reported by these participants included the mental and physical demands of the programme, difficulties with participation in daily life whilst wearing the mitt restraint and the physical effect of muscle fatigue and pain (Borch et al., Reference Borch, Thrane and Thornquist2015). The Home-based CIMT for patients with upper limb dysfunction after stroke (HOMECIMT) trial (Barzel et al., Reference Barzel, Ketels, Stark, Tetzlaff, Daubmann, Wegscheider and Scherer2015) interviewed stroke participants in the chronic phase of recovery (n = 13), and their family members (n = 9) on their perceptions of completing a four week home-based CIMT programme (Stark et al., Reference Stark, Färber, Tetzlaff, Scherer and Barzel2019). Participants in this study had completed two hours of practice each weekday with the support of a non-professional coach (family member) and mitt wear in addition to receiving five therapist visits during the programme (Barzel et al., Reference Barzel, Ketels, Stark, Tetzlaff, Daubmann, Wegscheider and Scherer2015). Participants in the HOMECIMT trial reported challenges such as a lack of adequate therapist support, difficulties with motivation and differing expectations of therapy workload when CIMT was delivered at home (Stark et al., Reference Stark, Färber, Tetzlaff, Scherer and Barzel2019). Some participants and coaches found the experience of spending more time together beneficial, whilst others did not (Stark et al., Reference Stark, Färber, Tetzlaff, Scherer and Barzel2019). What remains unclear is what factors influence service users’ decision to participate in CIMT in the first instance, and what service users perceive to be the factors that support adherence to these intensive programmes, as well as perceived programme benefits.

Behaviour change frameworks can be used by clinicians to identify key factors that are needed for a behaviour to occur, such as supporting adherence to health programmes (Atkins et al., Reference Atkins, Francis, Islam, O’Connor, Patey, Ivers and Michie2017; Michie, Atkins & West, Reference Michie, Atkins and West2014; Michie, van Stralen & West, Reference Michie, van Stralen and West2011). The Capability, Opportunity, Motivation – Behaviour (COM-B) system is one such framework that can be used to understand the factors that influence a particular behaviour and to develop programmes that promote adherence (Michie et al., Reference Michie, van Stralen and West2011). The COM-B system has been used to evaluate barriers and enablers influencing both patient and clinician adherence to evidence-based interventions (Alexander, Brijnath & Mazza, Reference Alexander, Brijnath and Mazza2014), physical activity (Flannery et al., Reference Flannery, McHugh, Anaba, Clifford, O’Riordan, Kenny and Byrne2018) and adherence to upper limb rehabilitation post-stroke (Levy et al., Reference Levy, Christie, Killington, Laver, Crotty and Lannin2021).

The aim of this study was to explore the experiences of adults who completed a CIMT programme as part of routine care, and the factors that supported participation using the COM-B system. Specifically, the study addressed three research questions:

-

(1) What factors influence the decision to participate in a CIMT programme?

-

(2) With consideration to the COM-B system, what are the barriers to and enablers of adherence to a CIMT programme?

-

(3) What were the perceived benefits and outcomes of completing a CIMT programme?

Method

Design, participants and recruitment

A descriptive qualitative study was conducted, embedded within a multisite implementation trial (the Australian Constraint Therapy Implementation study of the ARM [ACTIveARM]) (Christie, McCluskey & Lovarini, Reference Christie, McCluskey and Lovarini2018). A qualitative descriptive design was selected, using semi-structured interviews, as this approach offers a pragmatic yet rigorous approach for investigating phenomena (Stanley, Reference Stanley, Nayar and Stanley2015) and is well suited to programme evaluation (Patton, Reference Patton2015). Participants were recruited from a cohort of patients who had completed CIMT in routine care with one of nine neurorehabilitation teams during ACTIveARM (Christie et al., Reference Christie, McCluskey and Lovarini2018). CIMT programmes were structured based on the Australian Clinical Guidelines for Stroke Management which recommend that stroke survivors who receive CIMT complete a minimum of two hours of active practice per day, wear a restraint mitt for a minimum of six hours per day and use a transfer package for at least two weeks (Stroke Foundation, 2021). Teams selected a model of CIMT delivery that fitted within their local context and resources whilst adhering to these core CIMT components. Some teams delivered individual programmes whilst others delivered group-based programmes. Programme duration also varied between services, from two to four weeks. Participants were recruited by their treating therapist prior to commencing their CIMT programme. Interviews were conducted one month after CIMT completion during a follow-up appointment in which a researcher confirmed the participant’s willingness to be interviewed. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to their interview. Ethical approval was obtained from the South Western Sydney Local Health District Human Research Ethics Committee (ethics number HREC/16/LPOOL/419).

As this study focused on explaining a specific implementation related phenomena, criterion sampling was used to select participants who had an in-depth understanding and experiences of completing CIMT, and would be able to report on factors influencing their participation and adherence to a programme (National Cancer Institute Division of Cancer Control & Population Sciences, 2020; Palinkas et al., Reference Palinkas, Horwitz, Green, Wisdom, Duan and Hoagwood2015). To be eligible, participants had to have completed CIMT over two to four weeks and be able to consent to an interview. Health service interpreters were used for interviews with participants whose first language was not English. Interviews were conducted either face to face or via telephone. As this study explored factors that supported adherence to CIMT, participants who had only partially completed a CIMT programme (i.e. completing 70% or less of scheduled programme sessions) were excluded. Participants with a moderate to severe communication impairment, limiting interview participation, were also excluded.

Interview procedure

Individual interviews were conducted by investigators LJC, RR, NF and AH between May 2017 and July 2019. Participants were interviewed by a member of the team not involved in their clinical care. This approach aimed to elicit honest responses from each participant. The interviews were conducted at a location convenient to each participant, either the participant’s home or their local hospital. In the hospital setting, participants were interviewed in a private room to maintain confidentiality. Participants could have a support person present for the interview if they chose. The interviews ranged from 10 to 30 minutes in duration. All investigators audio-recorded the interviews and took additional field notes about the participants’ social circumstances.

Interview schedule

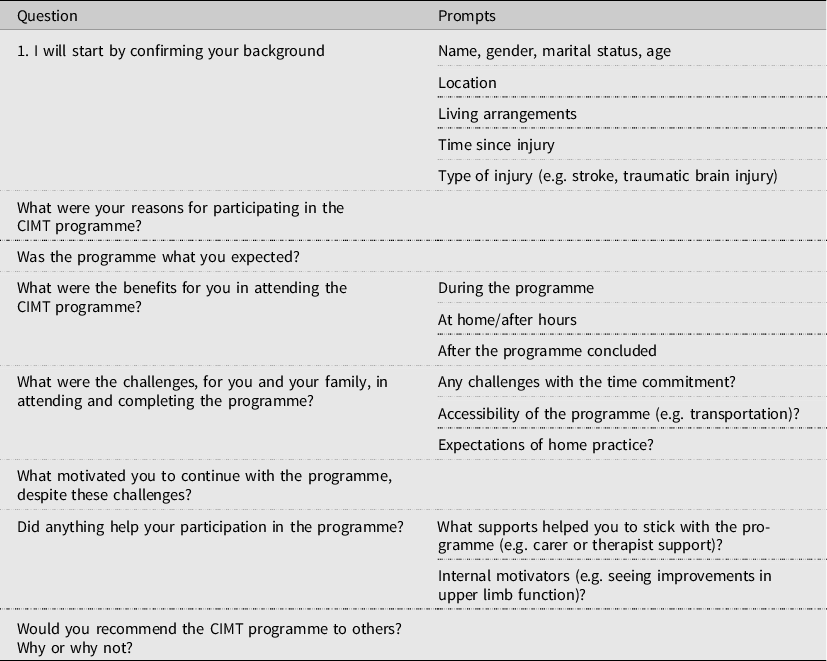

Interviews were conducted using a semi-structured interview guide (Table 1). Participants were first asked to describe their age, the circumstances surrounding their neurological event, their social situation and reasons for participating in CIMT. They then reflected on their expectations of the programme, benefits, challenges, factors that motivated them to continue despite the challenges, whether or not they would recommend the programme to others and reasons for their recommendations.

Table 1. Interview schedule

The investigators

LJC is an occupational therapist and health services researcher with 15 years clinical experience, primarily in neurological rehabilitation, and previous experience in qualitative research methods and implementation studies. RR is a physiotherapist and health services researcher with over 5 years clinical experience in neurological rehabilitation. NF is an occupational therapist and health services researcher with 15 years clinical experience. AH is a physiotherapist with 11 years clinical experience, predominantly in neurological rehabilitation. AM and ML are occupational therapists and health services researchers with previous experience conducting qualitative and implementation research.

Data analysis

All interviews were transcribed verbatim, anonymised and imported into NVivo (version 12) for analysis. Data were analysed in two phases. In phase one, the transcripts were initially coded using thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, Reference Braun and Clarke2006). Each transcript was read multiple times by the lead investigator (LJC). The first four interview transcripts were coded jointly by two investigators (LJC and RR) to develop an initial coding framework. The same two investigators then coded independently a further 17 interviews with findings compared and differences discussed throughout the coding process. The coding framework was developed and further refined over several cycles of independent data coding, with definitions assigned to each new code. An audit trail was maintained of decisions made in relation to the addition, removal or collapsing of codes, code definitions and preliminary themes. When the two investigators coded data to different codes, differences were resolved through discussion within the investigative team. LJC then independently coded all remaining interviews (n = 24) using the refined coding framework.

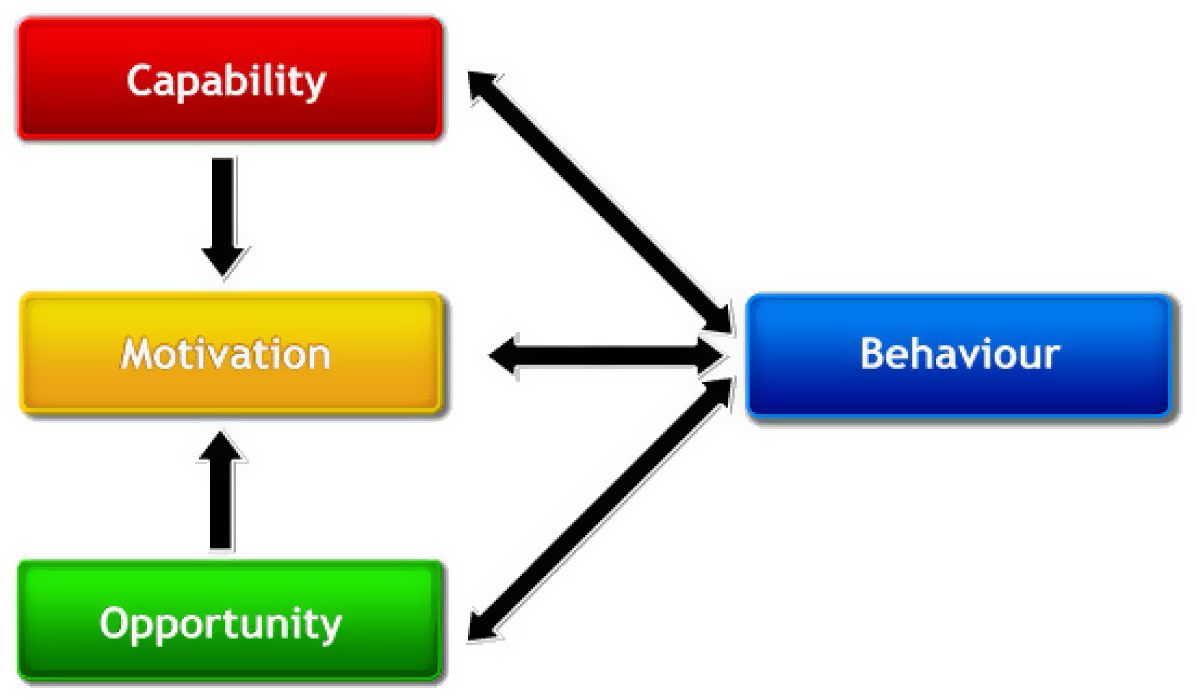

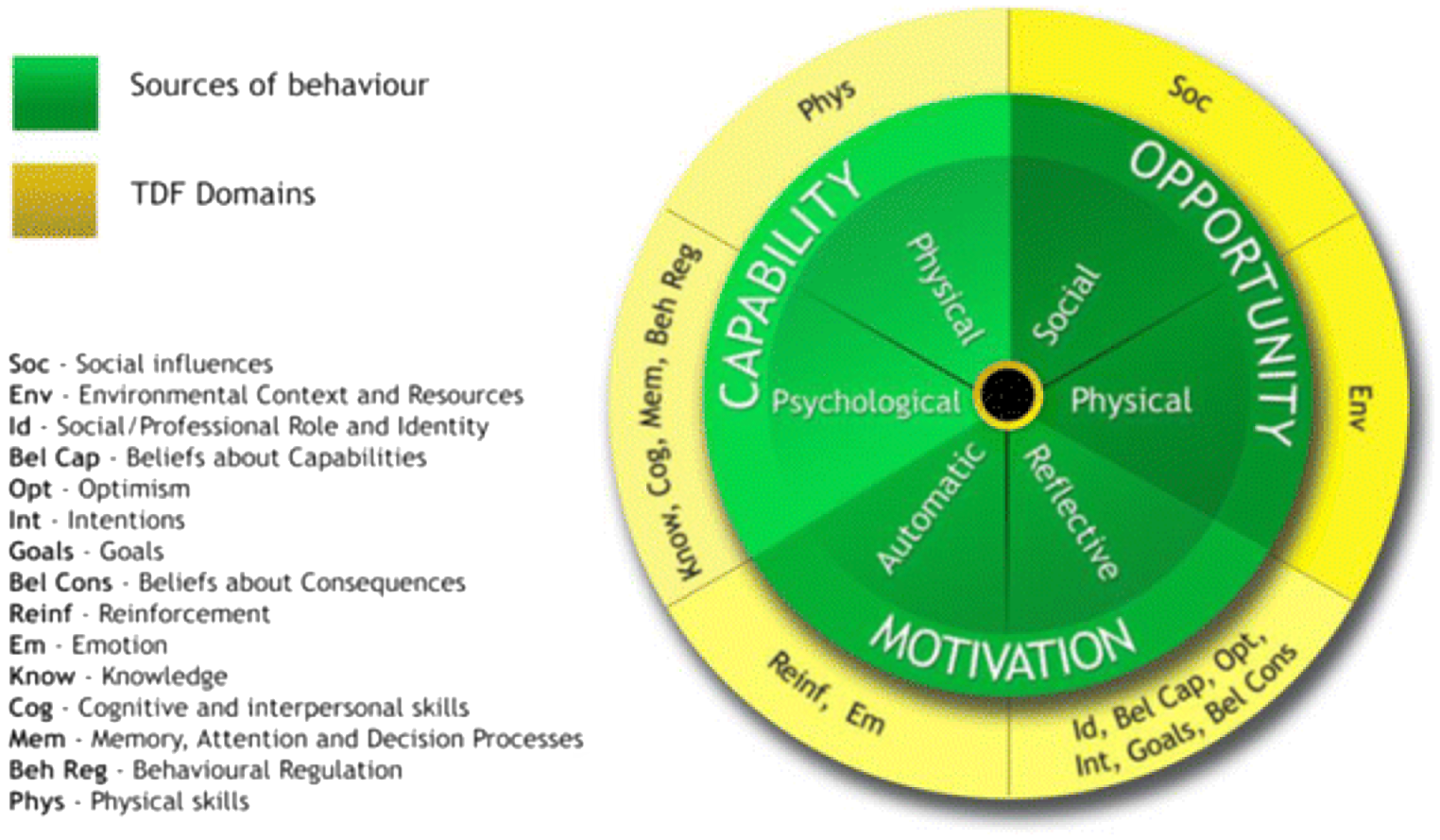

In phase two of the analysis, two investigators (LJC and RR) then deductively mapped the codes to the COM-B system of behaviour change and the Theoretical Domains Framework (TDF) (Cane, O’ Connor & Michie, Reference Cane, O’ Connor and Michie2012). The COM-B system (Fig. 1) represents behaviour as being generated by the interaction of three core components – ‘capability’, ‘opportunity’ and ‘motivation’ (Michie et al., Reference Michie, van Stralen and West2011). Capability refers to the person having the psychological and physical capacity to engage in the behaviour, including having the required knowledge and skills (Michie et al., Reference Michie, Atkins and West2014). Opportunity refers to external factors that support or prompt the person to complete the behaviour, including the physical and social environment, resources, affordability and time (Michie et al., Reference Michie, Atkins and West2014). Motivation refers to all the brain processes that energise and direct behaviour, including habitual processes, emotional responses and decision-making (Michie et al., Reference Michie, van Stralen and West2011). The validated Theoretical Domains Framework (TDF) was used to understand implementation challenges and linked to the COM-B to provide a more detailed understanding of underlying processes influencing behaviour (Atkins et al., Reference Atkins, Francis, Islam, O’Connor, Patey, Ivers and Michie2017) (Fig. 2). For example, the TDF domain of environmental context and resources can be linked to the COM-B system component of Opportunity (Physical).

Figure 1. The Capability, Opportunity, Motivation – Behaviour (COM-B) system for understanding behaviour.

Source: Michie et al. (Reference Michie, van Stralen and West2011). Figure available under Creative Commons attribution licence (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0/).

Figure 2. Linking of the Theoretical Domains Framework (TDF) to the Capability, Opportunity, Motivation – Behaviour (COM-B) system.

Source: Atkins et al. (Reference Atkins, Francis, Islam, O’Connor, Patey, Ivers and Michie2017). Figure available under Creative Commons attribution licence (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0/).

Along with the audit trail developed during phase one of the analysis, peer debriefing with two investigators experienced in qualitative research (ML and AM) was used throughout the data analysis phases to refine the initial coding framework and mapping of the data. These processes were used to enhance analytic rigour and the credibility of the findings (Nowell, Norris, White & Moules, Reference Nowell, Norris, White and Moules2017).

Results

Participant characteristics

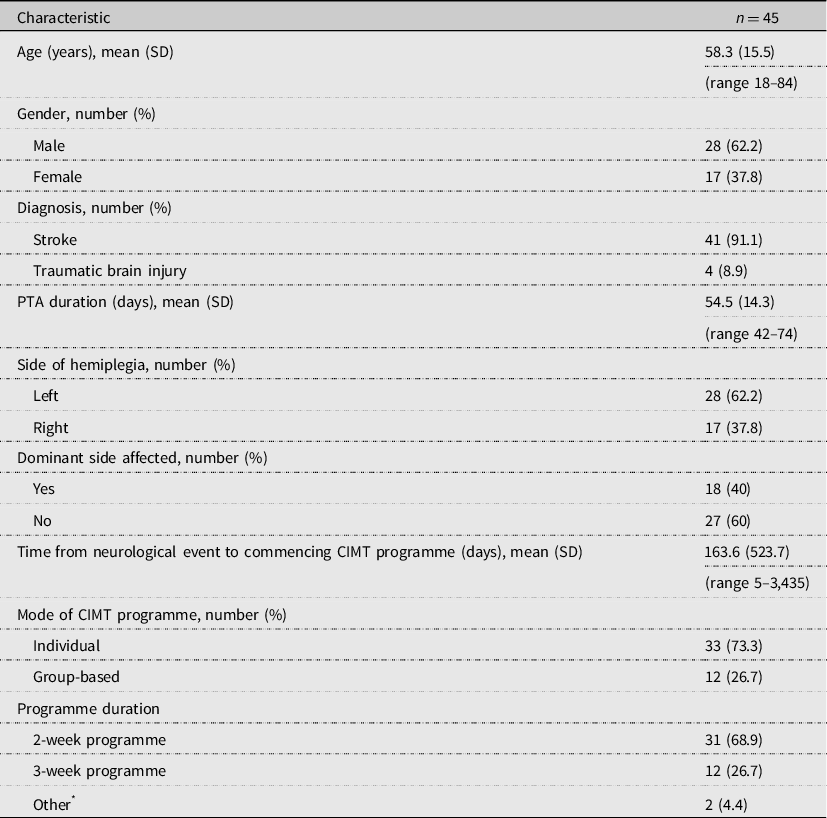

Fifty-three CIMT participants were eligible for the study, of which 45 stroke and TBI survivors who had completed a CIMT programme consented to be interviewed. Eight eligible participants declined to be interviewed due to personal preference or having other commitments. Table 2 provides details of the participants’ characteristics. The majority of participants were male (n = 28, 62.2%), had a diagnosis of stroke (n = 41, 91.1%) and had received an individual CIMT programme (n = 33, 73.7%) over a two week period (n = 31, 68.9%), with therapist input five days per week. One participant was initially set up with a CIMT programme by their therapist, including provision of exercises and the mitt restraint, but then completed their programme independently for two weeks, with limited coaching, feedback and progression of their programme provided by the therapist (Independent programme).

Table 2. Participant demographics

CIMT, constraint-induced movement therapy; PTA, post-traumatic amnesia; SD, standard deviation.

* Other: 1 × 4-week programme, 1 × independent programme.

There was variation in the age of the participants (mean age 58.3 years, SD 15.5 years, range 18–84 years) and time from neurological event to commencing a CIMT programme (mean 163.6 days, SD 523.7, range 5–3,435 days). These variations were due to the different types of services from which participants were recruited. Heath services interpreters were used in eight interviews.

Factors influencing agreement to participate in a CIMT programme

Participants identified three key factors associated with initially agreeing to participate in a CIMT programme. These were (1) their expectation of the programme to improve their pre-programme arm function; (2) their relationship with therapy staff and the broader multidisciplinary team and (3) wanting to return to valued roles, routines and activities.

Expectations of the programme to improve pre-programme arm function and impairment

The primary reason participants gave for agreeing to participate in CIMT was wanting to improve their arm function. Participants discussed wanting to improve their movement, strength, dexterity, sensation and functional use of their arm:

‘Because I didn’t want to be stuck how I was. I wanted to be able to move my arm and do things for myself’. (Participant 043)

Participation was seen as a potential way to accelerate their recovery, particularly for those in inpatient settings who felt participation may expedite their discharge from hospital:

‘Well I wanted to get better as quick as I could and as good as I could. And that seemed to be the way to go’. (Participant 010)

Relationship with therapy staff and the broader team

The relationship between participants, therapy staff and the broader multidisciplinary team was an important factor. Participants were recommended a CIMT programme mainly by occupational therapists and physiotherapists but were also referred to programmes by their treating medical specialist and, in one instance, a nurse. Participants discussed agreeing to participate in a programme simply because it was recommended or suggested by their therapist or doctor, and trusting that if they were recommending the programme, they were likely to benefit:

‘Just hearing positive things about the course from the instructors [therapists] and stuff like that, saying they’ve seen it work before’. (Participant 038)

Wanting to return to valued roles, routines and activities

Wanting to return to their valued roles, routines and activities was a key motivator for programme participation. Participants discussed wanting to improve their arm function to assist them with returning to activities including driving, work, carer roles for grandchildren and leisure activities such as craft and playing musical instruments:

‘My little boy, you know we go opal mining, we fish together, I go to sports with him … so I’ve got an active life … that’s a big motivation’. (Participant 004)

Another motivator was to regain independence in daily activities, to reduce the level of support they required from others:

‘I didn’t want to end up, for example, needing assistance in the bathroom … because I’m a very personal person. I didn’t want to be calling people … I don’t like to be an annoyance for others’. (Participant 031)

Barriers to and enablers of CIMT programme adherence

Barriers to and enablers of CIMT programme adherence were identified and mapped onto the six components of the COM-B system and 12 of the 14 domains of the TDF. The components Opportunity (Social) and Motivation (Reflective) were most prominent. The TDF domains that influenced programme adherence were: (1) physical skills; (2) knowledge; (3) environmental context and resources; (4) social influences; (5) emotion; (6) intentions; (7) goals; (8) beliefs about capabilities; (9) beliefs about consequences; (10) social/professional role and identity; (11) cognitive and interpersonal skills and (12) behavioural regulation. Key barriers and enablers to CIMT adherence mapped to COM-B components and TDF domains, and supporting exemplar quotes are outlined in supplementary Table 1.

Capability (Physical)

Physical skills

Participants reported that whilst CIMT was intensive, they were generally able to tolerate the programme. However, some participants experienced mental and physical fatigue when undertaking CIMT. A small number of participants (n = 3) also reported experiencing some discomfort in their arm during CIMT due to repetitive use. Participants were able to overcome these barriers through a variety of strategies such as taking a rest after their CIMT session. Having tasks within the CIMT programme set at an appropriate level of challenge for participants’ abilities helped participants maintain motivation and manage fatigue.

Capability (Psychological)

Knowledge

Participants discussed that being provided with education about what their CIMT programme would entail and the programme’s intensity was important in supporting them to first agree to and then adhere to their programme. When there was a lack of information provided by staff, participants and their family members were unsure about what to expect from a programme or what the expectations were from the therapists about the level of involvement from family members.

Cognitive and interpersonal skills

For some, ‘mentally preparing’ themselves for CIMT was needed. They described how it was important for them to acknowledge, prior to the programme beginning, that it would be challenging and intensive but that the short duration made this challenge more manageable.

Opportunity (Physical)

Environmental context and resources

When discussing the environment, the structured nature of CIMT programmes was seen as an enabler, and if programmes were not structured well, this was viewed as a barrier to programme adherence. Programmes that were perceived by participants to be disorganised and lacking structure were viewed negatively, particularly if participants felt they had been left to complete tasks on their own with limited therapist guidance. Participants reported that structured programmes that included the use of the behavioural contract and a structured timetable helped them feel accountable to the therapists.

Participants who attended CIMT as an outpatient reported that the daily travel needed to undertake the programme was a barrier, as many were unable to drive and were reliant on family members to assist them. Conversely, two participants who had received home-based CIMT reported the reduced need to travel as one of the benefits of a home programme. For participants undertaking CIMT in an inpatient setting, their programme was often viewed as a way to fill the time, as they had extended periods of being alone and not engaged in activity.

For participants from culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds, the use of additional resources including interpreters and translated materials, that had been developed for the ACTIveARM study, were seen as beneficial in supporting their participation.

Opportunity (Social)

Social influences

Social support was a critical factor in supporting adherence to CIMT. Support was provided in a variety of ways, including by family members, other group participants, staff and allied health students. Family members were often actively involved in CIMT and this was generally viewed by participants as being beneficial, for example, in supporting the completion of homework. Family members were also important in providing participants with general encouragement and positive feedback outside of therapy times.

For participants who completed group-based CIMT, social support from other participants was described as an enabler to programme adherence. Participants described developing friendly rivalries with other group members as well as developing a sense of camaraderie within the group. Participants reported that the support provided by therapy staff and students during their programme was a common enabler of adherence. The positive attitude of the therapists, and their coaching and encouragement helped to maintain participants’ motivation and supported adherence.

Motivation (Automatic)

Emotion

Participants often reported feeling very frustrated during their CIMT programme, especially during the first few days, as they were attempting tasks they had not tried since their neurological event and finding them difficult to complete. At such times, having support from the therapist was critically important. Once improvements in arm function were seen, their frustration diminished, and they were able to continue with their programme. Participants also discussed that the repetitive nature of the exercises could at times lead to boredom and reduced motivation.

Motivation (Reflective)

Motivation was a key enabler of programme adherence, mapping to the five TDF domains of social/professional role and identity, beliefs about capabilities, intentions, goals and beliefs about consequences. Self-motivation, self-belief, a commitment to succeed, tailoring of programmes to personal goals and seeing improvements were all important influences.

Some participants described themselves as having high levels of internal motivation to improve and felt this part of their personality had helped them adhere to their programme, describing it as being in their nature. Participants discussed the importance of having a positive belief that they would improve and being committed to achieving their goals. This commitment assisted them in persevering with their programme, even when it was challenging.

Another important enabler to programme adherence was the tailoring of CIMT to participants’ specific goals and interests. Participants reported this approach assisted with keeping programmes engaging and supported ongoing motivation. Participants also reported that seeing improvements in their arm function motivated them to continue with their programme.

Perceived benefits and outcomes of completing a CIMT programme

The majority of participants (n = 33, 73.3%) stated they would recommend CIMT to others. Perceived benefits associated with completing a CIMT programme included overcoming learned non-use, increased independence as returning to valued activities (Supplementary Table 2).

Overcoming learned non-use

Participants described using their affected hand more automatically in daily activities than prior to their CIMT programme, overcoming learned non-use of their affected hand. Participants described developing an attitude of ‘move it or lose it’ after programme, consciously looking for opportunities to use their affected hand in daily tasks:

‘In these pots … with the veggies, the weeds just keep coming. I’ll start off with my right and then I think, no, use the left … yeah, I try to be mindful’. (Participant 031)

Increased independence and returning to valued activities

Some participants reported that a key benefit of their CIMT programme was being able to do more activities independently, with reduced help from others. Some participants believed this increased functional independence had contributed to them being able to return to living at home alone:

Participant 001: ‘Well, it was a challenge because I wanted, to me I thought to myself, if you can do this, it’s your ticket out’.

Interviewer: ‘So really your main motivation was to go home?’

Participant 001: ‘To get out, back here [home], not have to be in a nursing home’.

Whilst a small number of participants reported seeing minimal or no improvement in their arm function post-programme (n = 5, 11.1%), all other participants reported seeing a range of improvements in upper limb strength, movement and, in one case, a reduction in pain:

‘After the CIMT, my fingers can do a lot of things. I mean, not quite as normal as … before … the stroke, but almost normal … I thought I could never have the chance to play piano again because the fingers didn’t work, but now I’m toward playing it again’. (Participant 060)

Improvements in arm function supported a number of participants to return to important activities including work and driving:

‘It gave me the courage that I could get back to my trade again. I managed to do a haircut there as well at the end of the program … which left me with so much hope that I will get back there again … I just need to increase my speed, but my confidence is there, otherwise I wouldn’t have been confident to do it, to try it, or who would have let me try it, you know?’ (Participant 037)

Discussion

The results of this study found that several factors contributed to participants’ initial decision to participate in CIMT and their ongoing programme adherence, including receiving programme education, social support, internal and external motivation factors such as tailoring programmes to individual goals and interests, physical factors and environmental factors including transport.

A critical factor that influenced patient participation was social support and encouragement offered by family, other group participants and the therapy team (including students). Family support was a key influence in a number of ways, such as providing physical assistance to complete programme components such as homework, providing encouragement during structured training and providing social support. As family members play a vital role in supporting adherence and, thus, overall effectiveness of CIMT, providing family members with adequate education and knowledge is critical. A recent study developed and evaluated the feasibility of delivering a structured psychoeducational intervention to support family members and stroke survivors during CIMT delivery and to prepare family members for their role as CIMT supporter (Blanton et al., Reference Blanton, Scheibe, Rutledge, Regan, O’Sullivan and Clark2019). The intervention was delivered in modules via an interactive workbook. Content included goal planning, education on safety in relation to mitt wear during a programme and the behavioural contract, observation of exercises and education on practice adaptations if tasks were too difficult. Daily check-ins were provided by the therapist with the participant and carer to discuss problems encountered in the home and strategies to support carers in their caregiving role (Blanton et al., Reference Blanton, Scheibe, Rutledge, Regan, O’Sullivan and Clark2019). The intervention was acceptable to stroke survivors and their care partners, resulting in high levels of CIMT adherence and reduced family conflict (Blanton et al., Reference Blanton, Scheibe, Rutledge, Regan, O’Sullivan and Clark2019). Within the current study, despite teams being provided with some educational resources for patients and their families about CIMT, some participants and families reported receiving limited information. Thus, the routine use of interventions as described by Blanton and colleagues, to support families to prepare for their role as a supporter prior to and during CIMT delivery should be considered when planning for CIMT implementation, to increase programme adherence.

Another important element was the support provided by other patients or peers. Participants who receive group-based CIMT may not only achieve better motor function outcomes than those who receive individual CIMT (Doussoulin, Rivas, Rivas, & Saiz, Reference Doussoulin, Rivas, Rivas and Saiz2018), but receiving CIMT in a group-based format may also improve social outcomes such as the giving and sharing of advice and information (Doussoulin, Saiz & Najum, Reference Doussoulin, Saiz and Najum2016). Doussoulin and colleagues suggest that the superior outcomes in group-based CIMT are because there is greater opportunity for stroke survivors to support each other, and for collective problem-solving to overcome challenges to daily arm use. There is also competition between group members, resulting in greater motivation and programme commitment (Doussoulin et al., Reference Doussoulin, Saiz and Najum2016). Within our current study, participants who received group-based CIMT reported similar benefits to those demonstrated in the study conducted by Doussoulin and colleagues (Reference Doussoulin, Saiz and Najum2016). Given the social and motivational benefits of group-based CIMT and that groups can be run with less therapist resources than individual programmes, provision of group-based CIMT may be a useful alternative to individual programmes in supporting participant engagement and adherence. Group-based programmes may also be more feasible to deliver within finite health resources, particularly public health settings (Brogårdh & Sjölund, Reference Brogårdh and Sjölund2006; Henderson & Manns, Reference Henderson and Manns2012). The inclusion of ‘how to’ guides with the clinical practice guidelines for stroke management, with recommended strategies that support programme adherence, such as using group based models and involving supporters, may assist clinicians with improving CIMT adoption in practice.

Participants reported that they enjoyed CIMT and found it to be a way to ‘fill the time’. They also reported that CIMT helped them to learn skills they could continue to work on as part of their recovery after their programme finished. A current challenge in neurological rehabilitation is that while high doses of interventions are needed to achieve a benefit, patients frequently spend large periods of time alone and inactive, completing non-therapeutic activities (Hassett et al., Reference Hassett, Wong, Sheaves, Daher, Grady, Egan and Moseley2018; King, McCluskey & Schurr, Reference King, McCluskey and Schurr2011). Routine provision of CIMT, particularly when accompanied by family/carer education to support programmes outside of direct face-to-face therapy time, may be one strategy that could assist in addressing this practice gap.

Strengths and limitations

Trustworthiness

We used a range of strategies to enhance the credibility, dependability and confirmability of our interpretation of the data and thus the trustworthiness of the findings. These strategies included the use of validated theoretical frameworks to guide the data analysis and interpretation of the study findings, peer debriefing, investigator triangulation during the data collection and analysis, and maintenance of an audit trail. This study involved clinicians delivering CIMT and collecting associated outcomes within usual care, without additional staffing resources. Programmes were delivered in a real-world context, with a diverse sample, including participants from diverse cultural backgrounds, recruited from five hospitals and nine different neurorehabilitation teams, at varying stages of recovery. The diversity of the sample and settings included within this study supports the transferability of the findings to other public health services.

Limitations

A limitation of the study is that we were unable to confirm the interview transcripts and our preliminary findings with our participants (known as member checking) due to a lack of resources to prepare these documents in languages familiar to our participants. We also did not include people with a communication impairment, which may limit the transferability of the findings. Second, whilst we interviewed a large number of participants about their experiences of completing CIMT, due to our strict purposive sampling criteria, we did not conduct any interviews with people who were eligible for and offered CIMT but declined to participate, nor did we interview people that only partially completed a CIMT programme. Whilst our findings provide valuable insights into the factors that support CIMT adherence, we did not explore the barriers and facilitators to CIMT adherence from the perspective of people who did not finish a programme. Rehabilitation research has identified that the preferences of patients, therapists and other rehabilitation clinicians in relation to rehabilitation service delivery can differ (Laver, Ratcliffe, George, Lester & Crotty, Reference Laver, Ratcliffe, George, Lester and Crotty2013). It is well established that when patient preferences for treatment are taken into account, compliance improves, leading to improved outcomes (Shingler et al., Reference Shingler, Bennett, Cramer, Towse, Twelves and Lloyd2014). Therefore, future research should explore the reasons why people decline CIMT, to gain a greater understanding of the factors that influence patient preferences and patient decision-making, and the information, support and programme structures that are required to improve patient engagement. Finally, we interviewed only a small number of people with TBI within this sample, reflective of the proportion of people who were provided with a CIMT programme within usual care. Future research should further explore the experiences of people with TBI in participating in a CIMT programme, given the limited exploration of this patient population in the past.

Implications for clinical practice

Our findings highlight the importance of therapists providing potential CIMT participants and their families with adequate education about CIMT to assist them in preparing for and participating in a programme. Sharing the experiences of participants who have successfully completed CIMT with potential participants, for example through videos, may be one strategy to support programme preparation and participation. Greater use of group-based CIMT programmes in practice may also enhance CIMT delivery and participant adherence, particularly in settings with limited therapist resources.

The importance of therapists providing ongoing coaching, encouragement and feedback to participants to maintain motivation was also identified. These elements of participant/therapist interaction have been highlighted as an important part of the CIMT protocol (Boylstein, Rittman, Gubrium, Behrman & Davis, Reference Boylstein, Rittman, Gubrium, Behrman and Davis2005; Morris, Taub & Mark, Reference Morris, Taub and Mark2006). Modified CIMT protocols with reduced amounts of coaching and feedback provided to CIMT participants by therapists have not been as effective on arm function recovery as other protocols (Baldwin, Harry, Power, Pope & Harding, Reference Baldwin, Harry, Power, Pope and Harding2018; Barzel et al., Reference Barzel, Ketels, Stark, Tetzlaff, Daubmann, Wegscheider and Scherer2015). Within our current study, participants discussed the important influence of receiving encouragement, coaching and positive feedback from their therapist to maintain motivation and adhere to their programme. Therefore, it is essential that therapists include these elements when delivering CIMT.

Conclusions

Our study provides insights into the factors required to support stroke and brain injury survivors to participate in CIMT. For therapists delivering CIMT, we recommend providing additional educational supports for both participants and their family members to maximise CIMT programme uptake. During programme delivery, the consistent provision of positive feedback and coaching to participants in alignment with CIMT principles, and the inclusion of social support structures such as group-based programmes and family involvement can further enhance programme adherence.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/BrImp.2022.18

Acknowledgements

We thank the Occupational Therapy and Physiotherapy departments of Liverpool, Bankstown, Braeside, Campbelltown and Camden Hospitals for participating in the study and the ACTIveARM advisory committee for support throughout the study.

Financial support

This study was funded by the New South Wales Ministry of Health Translational Research Grants Scheme (project number 28). The funder had no involvement in the study design; in the collection, analysis and interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; or in the decision to submit the article for publication.

Conflicts of interest

Lauren J. Christie has no conflicts of interest to disclose. Reem Rendell has no conflicts of interest to disclose. Annie McCluskey has no conflicts of interest to disclose. Nicola Fearn has no conflicts of interest to disclose. Abigail Hunter has no conflicts of interest to disclose. Meryl Lovarini has no conflicts of interest to disclose

Ethical standards

The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committees on human experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008. The South Western Sydney Local Health District Human Research and Ethics Committee (ethics number HREC/16/LPOOL/419) approved this study. All participating hospitals subsequently provided ethical governance clearances prior to data collection. All participants gave written informed consent before data collection began.