Published online by Cambridge University Press: 09 November 2011

2 With four other pewter tablets, not yet published, during excavation by the Museum of London. Helen Hatcher analysed it by XRF in the Research Laboratory for Archaeology, Oxford, and found that it averaged (in round figures) lead 40%, tin 60%, with traces of other metals. The other four tablets, although similar in composition, do not bear related texts; the most important is a Greek metrical phylactery against ‘plague’. Jenny Hall made them available to RSOT, who has published this tablet more fully in Henig, M. and Plantzos, D. (eds), Classicism to Neoclassicism: Essays dedicated to Gertrud Seidmann (1999), 105–10.Google Scholar

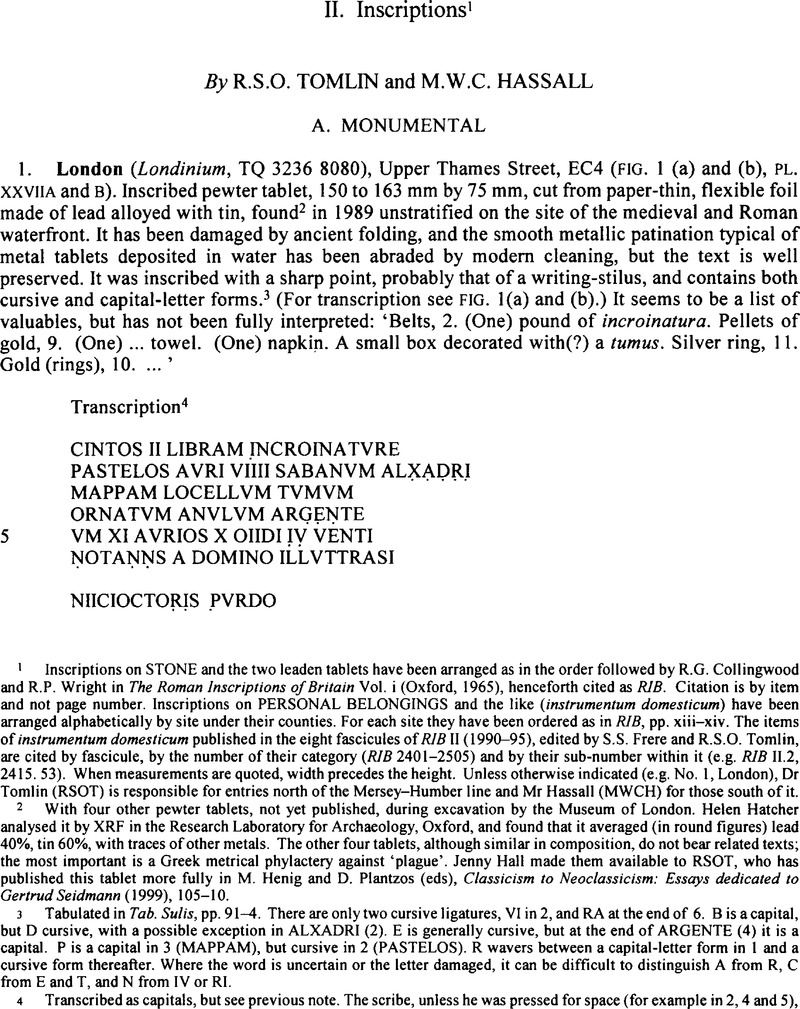

3 Tabulated in Tab. Sulis, pp. 91-4. There are only two cursive ligatures, VI in 2, and RA at the end of 6. Bis a capital, but D cursive, with a possible exception in ALXADRI (2). E is generally cursive, but at the end of ARGENTE (4) it is a capital. P is a capital in 3 (MAPPAM), but cursive in 2 (PASTELOS). R wavers between a capital-letter form in 1 and a cursive form thereafter. Where the word is uncertain or the letter damaged, it can be difficult to distinguish A from R, C from E and T, and N from IV or RI.

4 Transcribed as capitals, but see previous note. The scribe, unless he was pressed for space (for example in 2, 4 and 5), separated words. Recognizable words have been separated here, but difficulties remain in 5, 6 and 7. A line-by-line commentary follows.

1. CINTOS II. The accusative is ‘a sort of unmarked case which in accounts and lists could be given to the nouns signifying the object(s) bought / sold’ (Adams in JRS 85 (1995), 114). The substantive cintus is unattested, but CINTOS is an acceptable Vulgarism for cinctos < Classical cinctus; cf. cinto (‘belt’) in modern Italian.

LIBRAM INCROINATVRE, libram incroinatur(a)e. The metal is creased and split after M, and the sequence NCR would be impossible at the beginning of a new word without a preceding vowel; but there is space after M for I, and possible trace of it in the damage. The substantive incroinatura is not attested, but the word might be corrupt; two verbal nouns, both hypothetical, may be suggested, (i) incoctura (‘tinning’), from the verb incoquere used by Pliny (Nat. Hist. 34. 162) of ‘tinning’ vessels; hence they were called incoctilia (ibid), an adjective also applied to the ‘tinned’ (perhaps silvered) leaf-stops which contrast with the gilt letters of an inscription (CIL viii 6982). (ii) incoriatura (‘leather fittings’), from a presumed verb corio(r), ‘make corium, leather’, like the unique verbal noun coriatio found in Tab. Vin'dol. II, 343.40 (with JRS 85 (1995), 108). If CINTOS II is indeed ‘two belts’, this might be the bronze buckles, strap ends, belt-stiffeners, which would have belonged to them, (ii) is closer than (i) to incroinatura, but they are both only guesses.

2. PASTELOS AVRI VIIII. PASTELOS is the accusative plural of pastelus, an acceptable Vulgarism for pastillus, a diminutive ofpanis (‘loaf’) used of bun-like objects; it is usually found in the medical sense of ‘pill’. So perhaps a ‘pellet’ of gold, either a gold bead, or more likely a nugget or smelted granule.

SABANVM is a (linen) towel. Diocletian's Prices Edict lists various types and qualities and, since one is explicitly ‘Gallic’, Holder, Altceltischer Sprachschatz (s.v.), collects many other references. But none of them throws light on ALXADRI, if this qualified sabanum.

ALXADRI. The dotted letters are the likeliest reading. With its backward-curving second stroke, ‘D’ is unique in this text; it seems to be an ill-formed capital-letter D, rather than A or R. Next comes the same visual combination as in 7, where it seems to be RI. Egypt was a major source of linen cloth, and ‘Coptic’ linen towels survive, so it may be conjectured that ALXADRI is an error or a scribal contraction for Al(e)xa(n)dri or even Al(e)xa(n)dri(num), ‘(one) Alexandrian towel’. But there is no evidence that they were exported as far as Britain, or even that the terms ‘Egyptian’ or ‘Alexandrian’ actually described a superior grade of towel.

3-4. LOCELLVM TVMVM ORNATVM. E has been written over I, as if the scribe first envisaged a diminutive in -illus. Locellus is a diminutive locus, a ‘little place’ for storage; cf. Valerius Maximus 7. 8.9, anulos in locellum repositos, ‘rings kept in a little box’. In view of the rings in 4-5, this is an attractive sense here. TVMVM ORNATVM would be descriptive of LOCELLVM, not a new item, if the accusative TVMVM were a solecism for the ablative required by ORNATVM, because attracted into the same case as the surrounding accusatives. This unknown substantive tumus might be cognate with tumulus (‘mound’), but possibly TVMVM is a syncopation of tympanium (‘drum’), a technical term recorded by Pliny (Nat. Hist. 9. 109) for a large pearl flattened underneath. Britain was a notorious source of pearls (Tacitus, Agric. 12.6).

4-5. ANVLVM ARGENTEVM XI AVRIOS X. Clearly a catalogue of finger-rings, with note of metal and number. AVRIOS is a Vulgarism for aureos. The scribe must have intended ARGENTEVM, but instead of GE he made two loops which resemble a late-Roman cursive E; and instead of NT, he has written AT. (Perhaps he missed out T, and added it by crossing the N; but more likely, as he wrote the third stroke of N, he thought he was already writing T.) ARGENTEVM is followed by another demonstrable error, the numeral XI: a singular noun followed by the plural ‘11’. Obviously the scribe meant’ 11 rings, 1 silver, 10 gold’, which would have been ANVLOS XI ARGENTEVM IAVREOS X, but by oversight he has syncopated it.

5-6. The right-hand corner is not inscribed. The writing goes up towards the end of both lines as if to avoid the split in the metal, which would thus seem to be original. The incised marks beyond it are due to the stilus slipping while writing TI at the end of 5.

OIIDI. This resembles the sequence in 7, NIICI, each being followed by an apparent noun or personal name in the genitive case (see below). Both OIIDI and NIICI are placed as the beginnings of ‘words’, but as letter-sequences they are impossible; so perhaps they consist of numerals and one-letter abbreviations.

IV VENTI. IV with its elongated I and diagonal third stroke can hardly be N. The personal name Iuventi (‘of Iuventius’) is possible, but the gap between IV and VENTI may indicate that the scribe intended IVMENTI, genitive of iumentum (‘beast of burden’). He wrote V variously with curving strokes (see ORNATVM), and with straight diagonals (see AVRIOS) like those of M; thus he may have written V for M here by mistake. There is another gap after NO in 6, suggesting that it ended a word, but if the scribe had intended IVVENTINO (the ablative of Iuventinus) he would surely have added the NO to 5, where there was plenty of room. A more attractive idea is that he actually intended INVENTARIO (‘inventory’), i.e. the list in 1-5.

NOTANNS A DOMINO. DOMINO is inevitable, and presumably A is its preposition. This isolates NOTANNS. The second N is not M, but its third stroke is cut by a short diagonal, followed apparently by another short diagonal, as if the scribe were inserting a small V.

ILLVTTRASI. The reading is fairly certain, but makes no sense. Perhaps the scribe interchanged two letters by mistake, and intended ILLUSTRATI, i.e. a domino illustrati (‘marked by the owner’).

7. NIICIOCTORIS. ‘RI’ is the same letter-combination as at the end of 2, and -oris is frequent as a genitive case-ending. But there is no obvious name or substantive here.

PVRDO. The word is undamaged and complete, but no such substantive or personal name, whether purdo or purdus, is known.

5 During excavation by the Museum of London Archaeological Service (MoLAS). Angela Wardle made it available and provided details.

6 With a metal-detector, some miles south of Swindon, east of which another ‘curse tablet’ has been found, at Wanborough (Britannia 3 (1972), 363-7). The finder made it available, and showed the find-spot to RSOT.

7 Commentary line by line.

1. do is apparently a centred heading above the text, but not part of it, since the petitioner writes in the third person (see 5, rogat). Compare dono in Tab. Sulis 9 and donavi in Britannia 26 (1995), 371, No. 1 (Uley), which are also centred, but below the text.

2. deo Marti. M is awkwardly formed in four strokes unlike M elsewhere, but otherwise the reading is certain. ‘Mars’ was second to ‘Mercury’ as a Celtic god (Caesar, Gallic War 6. 17); tablets were addressed to him at Bath (Tab. Sulis 33, cf. 97), and at Uley he is identified with'Mercury’ (A. Woodward and P. Leach, The Uley Shrines (1993), 121-3, Nos 2 and 3, and 128-30, Nos 24 and 84).

After Marti the first letter is A (or perhaps T), but the next 2-3 letters are faint and ambiguous. If ID belongs to id [est], it marks the end of the previous word; here SEA looks certain. One would expect the petitioner's name, or perhaps a cult-title of Mars.

3. The first 3-4 letters are as drawn, but ambiguous; they might end with either IV or P.

eculium might therefore be peculium (‘property’), but in view of the possible reference to a ‘beast of burden’ in 4, it is tempting to understand eculium < eculeum, otherwise equuleum (accusative), a ‘small [or young] horse’. The demonstrative eum would imply ‘that foal’ had been mentioned already, which is unlikely; so eum may be a slip for (m)eum, ‘my pony’. et secur[…] might be a second stolen object; the obvious restoration would be secur[im] (‘an axe’).

4. tidisse. The reading is certain, and the repeated E (probably et) marks the word-ending.

ilium iume[ntum] is the most likely reading, with acceptable trace of the first stroke of N and the tail of M. For a stolen iumentum (‘beast of burden’) see Woodward and Leach, 118, No. 1. This reading would support eculium (‘pony’) in 3.

5. rogat genium tuum, dom[ine]. After ROG enough survives to exclude ROGO. The first stroke of A has apparently been lost in a series of vertical score-marks (not drawn). Despite do (1), therefore, the tablet is written in the third person. Requests are usually made ‘by’ someone's ‘genius’ (per genium), not directly to it. This is also the first ‘curse tablet’ addressed to a god's ‘genius’. It is a variant of the formulaic address to the divine ‘majesty’ (for which see Tab. Sulis, p. 65, and cf. Tab. Vindol. II, 344, tuam maiestatem imploro). Neptune is invoked as domine in Britannia 28 (1997), 455, No. 1 (Hamble estuary), and Sulis as domina dea in Tab. Sulis 98. For two examples from Spain, see Habis 6 (1975), domna Fons, and J.-N. Bonneville, S. Dardaine, P. Leroux, Belo V: L'Epigraphie (1988), 21-4, No. 1, rogo, domina, per maiestate(m) tua(m).

6-9. These lines, although incomplete, must contain a variant of the non permittas formula (see Tab. Sulis, pp. 65-6), which denies the victim physical well-being expressed as a series of complementary or alternative actions (‘eating or drinking’, ‘waking or sleeping’, etc.). The first prohibition here is unparalleled, but for the second see Tab. Sulis 54, no[nil]l[i p]ermittas nee sedere nee iacere. However, the slight traces in the corrosion layer at the end of 8 do not suit iacere. 7. perannos novem is the first instance from Britain of this ‘magical’ length of time, but compare the formulaic time-limit of ante dies nov[e]m (‘before nine days’) in Britannia 25 (1994), 296, No. 2 (Weeting with Broomhill), where other instances are cited.

9. After three damaged letters comes a series of four strokes just like MI in permittas (8); after that, MBR is well preserved.

8 By Mark Aylward, who took them to Tullie House Museum, Carlisle, to which they have now been given by the landowner, Mr Carter. Ian Caruana sent full details including a drawing and a photograph. Tim Padley made them available at Tullie House (accession no. 1996.11).

9 The two letters AF(or P)[…] are damaged by the break between them. The first letter has no cross-bar and, in spite of the A above being barred, it is probably an open A. Otherwise it might be N or ligatured M, but difficult sequences of letters would result. If this is the beginning of a personal name, Ap[…] is much more likely than Ap[…]. There is a space to the left of the letter below, of which one-third of a circle survives (from 9 o'clock to 1 o'clock); it is too large to be part of S.

10 During excavation by Tyne and Wear Museums on behalf of North Tyneside Council (now at Wallsend fort, inv. no. WS.IM.510). Alex Croom sent a drawing, photograph, squeeze and other details.

11 Apart from Britannia 1 (1970), 306, No. 3, where its restoration is uncertain, there are 20 other instances from Britain of the phrase a solo. They are all Severan or later, like the lettering of this inscription (cf. RIB 1300), and they almost all refer to rebuilding. A non-religious building inscription longer than a ‘centurial stone’ is likely to have begun with imperial names and titles, and the likeliest restoration of the surviving letters in lines 1 and 2 would be COS and AVG. But if there were only one emperor, AVG would precede COS in his titulature. So this inscription probably named two emperors, both COS, but jointly AVGG. (For an example see RIB 1234.) If they were Septimius SeverusandCaracalla, Geta Caesar would conveniently fill the line-width after AV[GG], which otherwise is difficult. After balifneumj might be an associated structure, e.g. balneum cum basilica a solo instruxit (RIB 1091) or an explanation of why the bath-house was rebuilt, e.g. balineum refect(um) [et] basilicam vetustate conlabsum a solo restitutam (RIB 605) and balinewn vi ignis exuslum … restituit (RIB 730).

12 By the farmer, John Dixon, who has given it to the Museum of Antiquities, Newcastle upon Tyne (accession no. 1999.7). Lindsay Allason-Jones sent a photograph and full details. For similar tombstones from High Rochester see RIB 1289 and 1291. The likeliest name of the deceased is Tertius or Tertullus, but there are other possibilities.

13 During excavation by Wessex Archaeology of a later settlement on the site of the annex to a first-century military base on the Roman road from Dorchester to Exeter. Andrew Fitzpatrick provided details and sent the sherds to RSOT.

14 Veia[…] might be read, as part of the rare name Veiatus. But a line has been scratched underneath VII, which is on a slightly different alignment from that of IA[…], and the forward slope of II differs from that of I, which is vertical. Therefore, since Ianuarius is such a common name, we prefer to read VII as a numeral.

15 With the next item during excavations for the Bowes Museum and Durham County Council directed by I.M. Ferris and R.F.J. Jones. See Britannia 9 (1978), 477Google Scholar, and 10 (1979), 347. Mr Ferris made them available with other graffiti too slight for inclusion here, which will be noticed in the final report now in preparation.

16 Before T and after N there is a little space uninscribed, but not enough to guarantee that the graffito is complete. This seems unlikely, since names that might be abbreviated to TON are rare. [AN]TON[I], [SVT]TON[IS], etc. are more likely readings.

17 With the next item during excavation by the Colchester Archaeological Trust directed by Howard Brooks, for the Colchester and North East Essex Co-operative Society. Mr Brooks provided details and rubbings of both items.

18 During excavation by MoLAS. Angela Wardle made it available and provided details.

19 This might be ATTI, ‘(property) of Att(i)us’, but the reading is very uncertain. AIIL for Ael(i), ‘(property) of Aelius’, seems more likely.

20 With the next item during excavation by MoLAS directed by Liz Howe. Roberta Tomber of the Finds and Environmental Service, Museum of London, provided details of both items.

21 The modius of 16 sextarii was a dry measure also used for liquids, equivalent to 8.754 litres, so the amphora would have contained 59.089 litres. This is appropriate for a Dressel 20 amphora; they often carry graffiti indicating a capacity of 6 or 7 modii and some sextarii. See RIB II.6, p. 33.

22 During excavation by the Department of Prehistoric and Romano-British Antiquities at the British Museum, directed by Tony Spence. The Keeper of the Department, Dr T.W. Potter, provided details and a drawing by S. Crummy.

23 The stamp resembles RIB II.5, 2485.9 (i) and (ii).

24 During excavation by MoLAS directed by Tony Thomas. Details of this and the next three items were provided by Fiona Seeley of the Specialist Services, Museum of London.

25 The graffito, if inverted, could be interpreted as [INGI]INVI, ‘(property) of Ingenuus’, but this seems less likely.

26 During excavation by MoLAS directed by Julian Bowsher, in advance of the Jubilee Line extension.

27 During excavation by MoLAS directed by James Drummond-Murray, in advance of the Jubilee Line extension.

28 The numeral ‘10’, or a mark of identification.

29 During excavation by MoLAS directed by Tony Mackinder.

30 This might indicate the capacity of the vessel, the number of its contents, or even its weight.

31 During excavations for Tyne and Wear Museums and the Earthwatch Institute, directed by N. Hodgson, P. Bidwell and G. Stobbs. (Find no. IM80, context 24279.) Dr Hodgson provided details and discussed the historical significance of the sealing.

32 This is the first example from Britain. For similar sealings see R. Turcan, Mgr a Moneta (1987), 20, Nos 12 and 13. It belongs to the reign of a sole emperor who used the title dominus noster. Septimius Severus was the first to do so formally, but for almost all of his reign he had a colleague (from 198 his son Caracalla) and his numerous sealings at South Shields bear the legend AVGG NN (RIB II. 1, 2411.1-16; Britannia 28 (1997), 466, Nos 36 and 37). So this sealing is later than the death of Geta (26 December 211), and at earliest belongs to the sole reign of Caracalla (212-17), if not later still. It is thus evidence for official use of the enlarged South Shields supply-base after 211, where all 24 granaries survived until the period c. 270-312 (see P. Bidwell and S.C. Speak, Excavations at South Shields Roman Fort, vol. 1 (1994), 28-33).

33 By Walter Elliot during fieldwalking on the fort area, near the north gate. Fraser Hunter of the National Museums of Scotland, Edinburgh, sent details. It is now in the museum.

34 By a metal detectorist. Fraser Hunter sent photographs and other details. It is being claimed as Treasure Trove and will be allocated to an appropriate museum, most probably the Hunterian.

35 In view of the find-spot, we treat it as Roman, but there is no close parallel from Britain. We would have expected an intaglio, retrograde inscription. LCG can be understood as the abbreviated three names of a Roman citizen, L(ucius) C(…) G(…).

36 A. Chastagnol, Inscriptions Latinesde Narbonnaise, II, Antibes, Riez, Digne (1992), Nos 121 (Vilbia Marcella), 123 (L. Vilbius Marcellus), 124 (Vilbi[…]), 125 ([… Vil]bius).

37 The only other instance of Vilbius’ noted by Chastagnol is L. Vilbiu(s) Fronto, a member of the Fifth Cohort of Vigiles at Rome in 205 and 210 (CIL vi 1057, 1058). His origin is unknown, but he might belong to the same family.

38 Thesaurus Linguae Latinae VII.2, 258-9, s.v. involo. Witches ‘steal’ a child (Petronius, Sat. 63), a fisherman ‘steals’ one fish without alarming the others (Pliny, Nat. Hist. 9. 181). In the pre-VuIgate translation of the Bible (the ‘Itala’), involare is used for the Vulgate's furari, of Joseph (Genesis 40.15) and Israelites (Exodus 21.16) sold as slaves, of stolen animals (Exodus 22.1 and 12), and of the body of Jesus (Matthew 28.13).

39 Information from Ian Caruana, who sent a photograph. It matches Horsley's drawing.

40 At the prompting of John Mann, who suspected an allusion to Commodus in line 2. The fullest description and discussion is by Coulston and Phillips in CSIR i 6, 157, No. 474. See also M. Rostovtzeff, ‘Commodus-Hercules in Britain’, JRS 13 (1923), 91–109.Google Scholar Tim Padley made the stone available, and Chris Howgego has discussed the coin-evidence.

41 Coulston and Phillips (see previous note) suggest that the aperture framed a statue of Hercules ‘so that the opening of the arch was behind the head’. A keyhole-shaped aperture would have neatly echoed the silhouette of head and shoulders.

42 In COMMILITON (4), the first (vertical) stroke of the first M leans slightly to the right, but in the second M it is quite vertical. The first stroke of N leans slightly to the right, whereas in SEXTANI (7) it leans slightly to the left. (These small variations are apparent on the stone itself, but not in Collingwood's drawing nor in the photograph published as CSIR i 6, pi. 107, No. 474.) A better criterion would be the angle of the second, diagonal stroke, measured by its distance along the base-line from the mid-point of the vertical stroke. It would have been 13 mm for M, 22 mm for N, but unfortunately the break in the stone, although it is 14 mm away, is too abraded at the edge for M to be eliminated.

43 Enough survives to eliminate F, I, P and R. There is no reason to think that unequivocal traces of N have been destroyed since Rostovtzeff saw the stone in 1920. His reading of CON seems to have been due to his wish to restore Conservator, ‘one of the most common epithets of Hercules’ ( JRS 13 (1923), 97Google Scholar), but in fact CONSERVATORIS will not fit the space available.

44 It can be calculated from the curvature of the arched opening, but the decisive argument is Richmond's restoration of the unit-title in 5-6. See the drawing to RIB 946. The other restorations in 3-4 and 7-8 are debatable, but do not affect the issue.

45 Coins were struck with the reverse legends HERC(VLI) ROM(ANO) CONDITORI and HERCVLI ROMANO AVG(VSTO) in Commodus’ 17th tribunician year (10 December 191-9 December 192), and ‘medallions’ with both legends in his 18th tribunician year, intended presumably for New Year's Day 193, which he did not live to see. The epigraphic evidence is collected by M.P. Speidel, ‘Commodus the god-emperor and the army’, JRS 83 (1993), 109–14.Google Scholar It amounts to the Dura altar (17 March 193) which calls him pacator orbis invictus Romanus Hercules; another military dedication, from Volubilis (AE 1920.48 = IAM ii 363), pius invictus felix Hercules Romanus; and an official dedication from Treba near Rome (ILS 400), pacator orbis felix invictus Romanus Hercules. The new titulature had reached Oxyrhynchus in Egypt probably by 11 October 192 (PSI ix 1036, in Greek), pacator orbis felix invictus Romanus Hercules.

46 Rostovtzeff had two reasons. (1) After identifying himself with Hercules, Commodus would have been offended by ‘the moderate and somewhat enigmatic language’ of RIB 946, so it must be earlier than 192. This is a matter of opinion; and it will be suggested that the inscription was accompanied by a statuette of Hercules-Commodus which made the identification explicit. (2) Rostovtzeff connects RIB 946 with the British victory of 184, but with almost two-thirds of the text lost, we do not know whether it celebrated a major victory or (like RIB 1142) a local success.

47 R1C iii, Commodus, Nos 616 and 629; Gnecchi, Medaglioni, p. 54.

48 RIC iii, Commodus, Nos 221, 581, 586, 591, variously HERC. COM. and HERC. COMMODIANO, dated by his 16th tribunician year (10 December 190-9 December 191).

49 The Dura altar, dedicated by a cohort Com(modiana), and ILS 400, dedicated by an ordo decurionum Commodianor(um), confirm the literary evidence of Dio Cassius 75.12; Herodian i, 14.8; and Hist. Aug. Commodus, 8.6-9.

50 CS1R i 6, 77, No. 190.