Article contents

Abstract

Information

- Type

- Roman Britain in 1969

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © R. P. Wright 1970. Exclusive Licence to Publish: The Society for the Promotion of Roman Studies

References

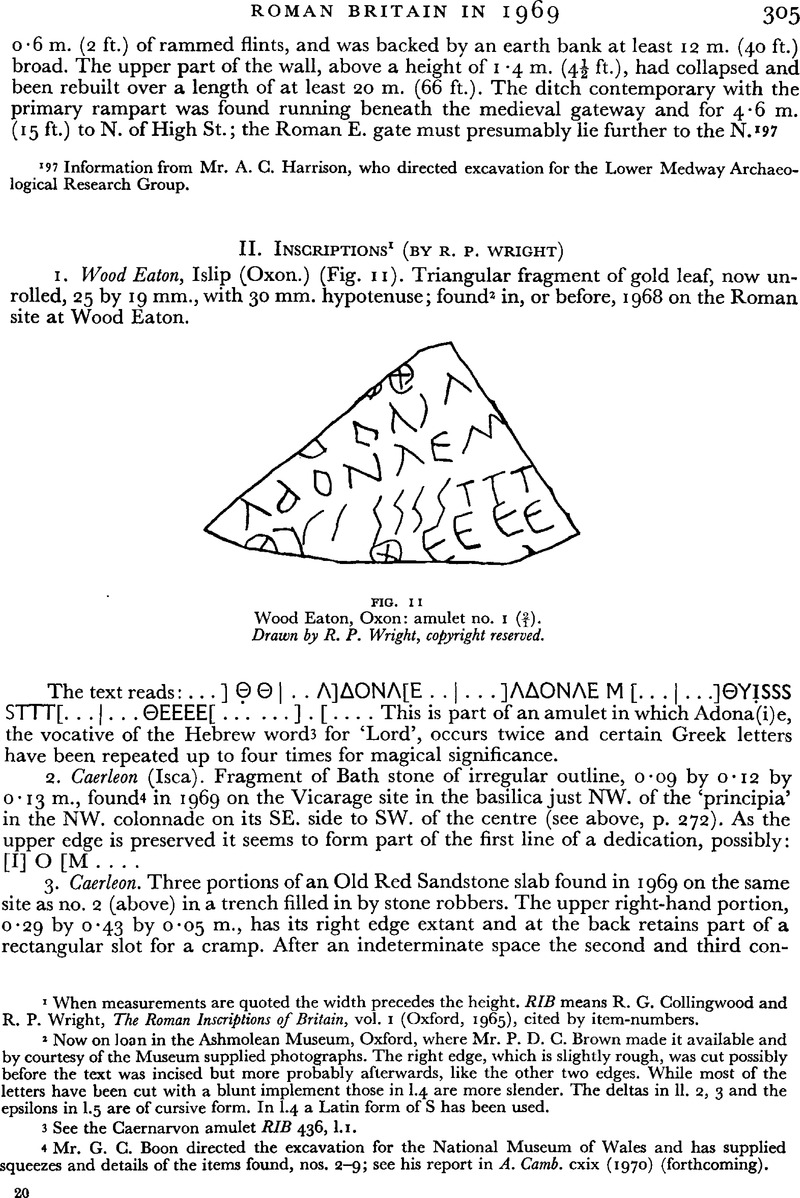

2 Now on Joan in the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford, where Mr. P. D. C. Brown made it available and by courtesy of the Museum supplied photographs. The right edge, which is slightly rough, was cut possibly before the text was incised but more probably afterwards, like the other two edges. While most of the letters have been cut with a blunt implement those in 1.4 are more slender. The deltas in 11. 2, 3 and the epsilons in 1.5 are of cursive form. In 1.4 a Latin form of S has been used.

3 See the Caernarvon amulet RIB 436, l.i.

4 Mr. G. G. Boon directed the excavation for the National Museum of Wales and has supplied squeezes and details of the items found, nos. 2–9; see his report in A. Camb. cxix (1970) (forthcoming).Google Scholar

5 The restoration has been worked out by the writer in correspondence with Mr. G. C. Boon and Dr. M. G. Jarrett and discussions with Professors E. Birley and S. S. Frere. Mr. C. Williams added details when he made a full-scale drawing for the National Museum of Wales. See Boon, A. Camb. forthcoming.

For I.O.M. et Genio see ILS 2182 (of A.D. 139) and RIB 915 (of A.D. 244–9). For Antoninus by itself as a description of M. Aurelius see ILS 1097, 1098 and 8973. For the pair of joint emperors Professor Birley thought that Commodus was more likely than Aur. Verus as Augg. is given in abbreviated form. He suggested that the legate was the legionary one, as on RIB 316 and 320, and not the provincial governor. Mr. Boon restored 11. 5, 6 and showed that the stone lay near the aedes, which had been restored. Unless restituit was inset it is preferable to take his alternative suggestion that T is to be taken as T(itus), and not as the terminal letter of that verb. The incomplete name is more likely to have been Esuvius than one of the rare names with similar beginning. Mr. Boon interpreted PR P as pr(imus) p(ilus) from Cagnat's index in Cours d'epigraphie latine, and Dr. B. Dobson provided the reference, CIL VIII 12579.

As there is insufficient room to fit the names of the primus pilus after leg. Augg. it seems necessary to inset the last two lines by about two letter-spaces and make T. Esuvius in 11. 6, 7 the subject of the supplementary verbs in the final line. The propenultimate and penultimate lines will have cited the legionary legate either in an ablative absolute or governed by sub. For dedications by primi pili at Lambaesis with their names preceded by dedicante and the legate's names in the ablative see CIL VIII 2533, 2535 or 2543; for a dedication by a cohort preceded by the legate's names in the ablative see CIL VIII 2536.

6 Professor S. S. Frere searched Kajanto, Cognomina and could find only Candidus and Candidius, apart from Didius, which seems too short a name for so much of it to have been rendered in ligature. Schulze, Eigennamen pp. 436–8, cites only these two names out of 27 instances of -idius.

7 It lay face downwards in the SW. portico of the swimming pool in the ‘palaestra’ in the Fortress Baths in the ‘praetentura’. It had been reused as nagging in a fourth-century building on the site of the dismantled portico.

8 Mr. J. K. Knight for the Ministry of Public Building and Works sent a squeeze and details. Grid ref. ST 33409074, within 12 m. of the place where JRS XLVI (1956), 147, no. 5 was found. Several worn and uninscribed slabs were also found, probably used as paving.Google Scholar

9 Mr. J. F. Jones made it available in Carmarthen County Museum, and Mr. G. C. Boon sent details and a drawing. Occupation material of c. 70–120 from the same area may mark a fort-site (see V. E. Nash-Williams, Roman Frontier in Wales, 2nd ed. M. G. Jarrett, 110).

10 Mr. A. D. Phillips gave details and facilities for studying this item and nos. 13 and 14 for the Archaeology Advisory Committee of York Minster.

11 Genio is frequent in dedications by collegia and has the merit of brevity, whereas pro sal(ute) is usually used on such texts for the names of emperors. In 1.2 the letters are of the same height as those of 1.1 but are more closely set and four ligatures are used. An abbreviated title of the guild has been lost. For BP Dr. G. Alföldy tentatively suggests ob p(romotionem(?)). Although promotio is rare, it occurs in SHA Anton. Diadum. 2 and in CIL III 14416 (ILS 7178). As the space is limited the cutter has reduced the word to one letter, which may have been understood in its contemporary context. In a verbal form it has been reduced to only two letters cum pr(omotus) s(it) in CIL VIII 2557,1. 31 (ILS 2354). It is successione promot (us) in CIL vi 3584 (ILS 2656). Dr. Alföldy cites ILS 2073 as an early example of a bf. named after an individual and thinks that Gordianus is cited as praetorian governor of Britannia Inferior in A.D. 216, and not as emperor (see Birley, A. R., Epigr. Stud. 4 (1967), 87).Google Scholar

12 See no. 12 (above). The stone is at Ordnance Datum 52, about 1·2 m. below the present floor of the Minster. The interpretation is in part due to Professor S. S. Frere. For opus on a building-stone see RIB 593 and 626.

13 See no. 12 (above). The slab lay at O.D. 46·7. Professor E. Birley helped with the interpretation of 11. 1,2 and suggested that e[x pr]a[e]f. would account for the extant letters. He can quote no other instance of Ant. Gargilianus, who remained in York after being praef. castrorum leg. VI. His son-in-law became a decurion of Eboracum.

14 As her reading of H.3,4 Dr. Elizabeth Okasha is giving ![]() in her forthcoming Hand-list of Anglo-Saxon Inscriptions (Cambridge U.P.).Google Scholar

in her forthcoming Hand-list of Anglo-Saxon Inscriptions (Cambridge U.P.).Google Scholar

15 By a schoolboy from Lanchester who pointed it out to the Revd J. W. Wilson, then Curate at Escomb, who brought it to the writer's notice, made squeezes and assisted in recording it. It had been laid on its side at a height of 3·77 m. from the ground in the W. side of the embrasure. About 3 mm. must have been trimmed away from the frontal edge of the top to make it fit the splay of the window.

16 Escomb lies 2·4 km. (1 ½ miles) SW. of Binchester; grid ref. NZ 189301. At Bitterne in Hampshire where stone is scarce, at least four milestones were incorporated in the late walls of Clausentum (RIB 2222, 2223, 2226, 2228). As three of them recorded the same emperor they must have come from three separate milestone sites. At Binchester, however, there must have been an abundance of stone at the fort, so that it would have been unnecessary to collect casual milestones from the roadside.

17 A survey of the instances indexed in CIL and AE has produced one example of A.D. 292–304 (CIL XII, 5520), two for Constantine I as Caesar (CIL IX 6068, XII, 5584), and about 52 instances for Constantine and his house. There are about 86 other examples for the rest of the fourth century. No instance is later than A.D. 395 apart from an apparent archaism under the Gothic king Theodericus (ILS 827; Diehl, Inscriptions Latinae Christianae veteres 35). For a fuller discussion see Wright, , Arch. Ael.4 xlviii (1970) forthcoming.Google Scholar

18 For Old Penrith see RIB 930; Ms. note by Collingwood. For Wroxeter see RIB 289. Reproduced by Haverfield in Victoria County History, Salop i. 247, fig. 21. The original was lost for some decades but was rediscovered in 1964 by Dr. G. Webster outside Wroxeter Museum (JRS lv (1965), 228); drawing by the present writer in Arch. Ael. loc. cit. The dimensions are 0·59 by 0·46 by 0·48 m.Google Scholar

19 From his excavations for the College of Education, Alnwick, Mr. R. E. Birley submitted this item and nos. 17, 18 and 21 (below). For Deae Matres see RIB 456, 586, 1424; for Matres suae 654 and 2055. There is no other instance of suae between the two nouns in Britain.

20 Govinus seems to be unmatched, but there are instances of a nomen Covius.

21 The farmer, Mr. I. McIndeor, had the slab carefully raised and stored and later generously presented i. to the Hunterian Museum, Glasgow, where it has received expert cleaning. When Mr. G. A. Williamson inspected it he informed Mr. E. A. Cormack and Dr. K. A. Steer. For a full discussion, here summarized, see Steer and Cormack in PSAS ci forthcoming. See also Steer, Discovery and Excavation in Scotland 1969, 23, Robertson, Anne S., Glasgow Arch. Jour. 1 (1969), 1CrossRefGoogle Scholar with plate and A. & Wendy Selkirk, Current Arch. (Jan. 1970) 196 with fig. and illustration on cover. The new text would be no. 10A in Sir George Macdonald's numbering from east to west in Roman Wall in Scotland (2nd ed. 1934), ch. X.

The stone was found face downwards in what seemed to be a shallow pit as if deliberately buried at a point about 3 m. south of the rampart of the Antonine Wall (Grid. ref. 5154 7234). Two splayed crampholes on the upper margin and one half-way down either side indicate that it had been pinned to some backing, presumably of masonry.

22 The cutter has abbreviated part of the formula to Imp. C. T. Ae(lio), as on certain other Leg. XX texts, RIB 2199, 2206, and 2208.

23 The coinage of A.D. 145–7 which recorded the victories in Britain portrays Britannia as an armed and watchful warrior (Mattingly, BMC iv. p. lxxxv). Dr. Toynbee has drawn attention to the A.D. 134–5 issue of Adventui Aug. Britanniae with Britannia in a long robe and patera in right hand (Cohen ed. 2 ii, 109 no. 28: Toynbee, Jocelyn, JRS xiv (1924) 147, pl. xxiv, 3; Mattingly, BMC iii, Hadrian after no. 1640). The designer of the sculpture may have used these coins of the preceding decade for his portrayal of the province and felt that spectators would apply this interpretation.Google Scholar

24 RIB 2197, 2198, As the second of these and the new discovery carry cramp-holes neither can be regarded as a ‘waster’. On Hadrian's Wall two pairs of stones placed on the inner faces of the north and south mounds of the Vallum marked the sector built by one century (Richmond, and Birley, , Arch. Ael.4 xiv (1937), 227), whereas the centurial stones on Hadrian's Wall itself were not placed on the north, or enemy, side of the structure.Google Scholar

25 Found by Mr. J. Boyle in driving a mechanical digger for an extension to Weir's bus garage. After the Rev. A. D. Eunson had interpreted the text the altar was acquired by the Hunterian Museum, Glasgow. Dr. Anne S. Robertson provided details and a photograph and Professor E. Birley gave information about the units and individuals on the inscription. See Anne S. Robertson, Glasgow Herald (27 Jan. 1970), 21; A. and Wendy Selkirk, Current Arch. (Jan. 1970), 197 with plate.

The superb condition of the lettering indicates that it had not been exposed to much weathering. As it is a dedication to Jupiter by a cohort it may have marked an act of loyalty at the beginning of one year and been formally buried at the beginning of the next like the sequence of altars found in pits at Maryport (Alauna) (See Wenham, , Cumb. and Westm. AAST xxxix (1939), 19). It may have been transferred from the site where it lay in Roman times, for there may have been some disturbance of this area in comparatively recent times.Google Scholar

26 Professor E. Birley can cite no instance of Publicius Maternus. None of the instances of Iulius Candidus fits this individual. For Bar Hill see RIB 2169, 2170. Birley thinks that the presence of a centurion of Leg. I Italica can best be explained when Septimius Severus drew detachments from the Danubian provinces, including Moesia, where this legion was serving, for his campaigns in Britain in A.D. 208–11.

27 See no. 17 (above). Mr. R. E. Birley provided a squeeze and a photograph.

28 Found by Mr. Morris at 12 Cannons Close (grid ref. TL 493221). Reported in C.B.A. Group 10, Thames Basin Archaeological Observers Group News Letter, July 1961. Wing Cdr. T. W. Ellcock sent full details but could not submit the counter as the owner proved to be untraceable despite protracted enquiries.

29 Now in the Townley Collection in the British Museum. Vetusta Monutnenta iv, 1799,1, no. 4; Whitaker, Whalley (4 ed.), 32 pl. 11; Watkin, Lanes., 150 with restored figure. R. C. Bosanquet read CONB … (in his MS. notes now stored with RIB files). The vessel matches den Boesterd type 27, Eggers Import type 144.

30 Mr. W. J. Rodwell submitted it for study. For Amatus see CIL IV 2486, x 3744. The nomen Amatius is much less likely. For the site see p. 291 above.

31 Professor B. W. Cunliffe sent it for study.

32 Dr. A. R. Hands sent the fragments; the readings were contributed by Dr. D. B. Harden. For the placing of this site in North Leigh parish see JRS lix (1969), 221Google Scholar, n. 102. For another object from this site see JRS lvi (1966), 221, no. 24. See Excavations at Shakenoak ii, forthcoming.Google Scholar

33 Mr. E. Greenfield conducted the excavation for the Ministry of Public Building and Works and sent the ring with full details. The first letter seems to be I with exaggerated serif, and not L. The C is reversed, the second S is on its side. The stop consists of three short verticals with a point above and below each one. For the site see p. 296 above.

34 JRS liii (1963), 163, no. 24, lix (1969), 240, no. 28. The latter has the same stop as that described in n. 33 (above). For fuller discussion see Wright in appendix to J. R. Collis's article on small finds from Owslebury in Antiq. Journ. (forthcoming). See RIB 129 for a local deity, CVDA, known only from a chance find at Daglingworth, Glos.Google Scholar

35 The fragments were pieced together mainly by the pertinacious work over several years of the late C. D. P. Nicholson, F.S.A. Lt.-Col. G. W. Meates made them accessible in 1964 to the present writer at the Gate House, Lullingstone Castle. In 1967 Kent County Council presented them to the British Museum, where they were placed on display in 1969. See Meates, G. W., Lullingstone Roman villa (London, 1955Google Scholar,) ch. xiii, Toynbee, J. M. C., Art in Britain under the Romans (Oxford, 1964), 224Google Scholar, pl. LVa, Painter, K. S., British Museum Quarterly xxxiii (1969), 131–43CrossRefGoogle Scholar, fig. 9, pl. LXVIa.

Although Meates thought that this plaster had been placed at the extreme west end of the wall, Painter (to R.P.W. in January 1970) explained that a slight amendment is needed to his report in BMQ. The fragments of the pillar to the right of the wreath in the chapel do not fit the remains of the pillar preserved in the angle of the wall. The position of the wreath remains unfixed; it may have to be placed further east, perhaps in the centre of the wall.

36 Toynbee, loc. cit., 225, pl. LV b, c; Painter, loc. cit., 141, pl. LXVIIa.

37 Until then the east end of the building had been sealed by a modern road. Toynbee, loc. cit., 225; Painter, loc. cit., 142.

38 Now in Guildhall Museum; Mr. P. R. V. Marsden provided details. For the stamp see CIL vii 1235 f.

39 Mr. J. S. Wacher sent these items and nos. 32 and 46 (below) for study for the Ministry of Public Building and Works. (For the site see p. 300 above).

40 CIL vii 1241(Calne); JRS xxvii (1937), 249Google Scholar (N. of Barbury Castle); ibid, xlii (1952), 107 (from the same Wanborough site and now in the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford, ibid, xlvi (1956), 152).

41 Now in the Corinium Museum, Cheltenham and Gloucester Museums. See Clifford, Elsie, JRS xlv (1955). 70. no. 8 (b), pl. xv 8 (b).Google Scholar

42 Mr. J. Bradshaw sent it for the Ashford Archaeological Society. The site is 3 miles due E. of Lympne (Lemanis) at grid ref. TR 07803440. A Drag. 45 mortarium base and coarse ware of the first to fourth centuries were found with it.

43 Camulodunum form S4A' (Hawkes and Hull, Camulodunum (1947), 182). Found by a Mr. Henderson at grid ref. TL 395240; sent for study by Wing Cdr. T. W. Ellcock.

44 Sent for study by Mr. A. P. Detsicas. There are several instances of the names Gargilianus and Garrulus.

45 Mr. L. P. Wenham deposited this item and no. 39 (below) for study. For the site see p. 280 above.

46 Mr. J. D. Bestwick sent details, rubbings and a drawing, for the Middlewich Archaeological Society. The workshop was in use in the middle of the second century A.D. An adjacent oven seemed to belong to the type used for producing salt from the local brine. See p. 282 above.

47 In his primary version the cutter sketched in thin cuts the letter M with an additional sloping stroke in the second apex. The remaining letters, about 40 mm. high, show no trace of any primary cutting. In his second version the cutter thickened the third and fourth strokes of the M and chipped out the further letters VRCA, to read AMVRCA.

It is possible to interpret the word as a personal feminine name Murca (see ILS 885). But it seems better in this industrial context to interpret the first letter as AM ligatured in which the sloping bar to indicate the A has in error been cut in the second, and not the first, apex. Amurca strictly means ‘the lees of olive oil’, and Cato R.R. 10, 4 speaks of dolia amurcaria. But as two large ‘dolia’ have survived and the sites for three more have been preserved it seems reasonable to interpret amurca as ‘the lees’ or ‘waste from brine’, thus distinguishing the purpose of this container from the others in the group. If it seems uncertain that an A was ligatured to the M there is a medieval instance of murca for amurca in a 14th-century glossary (R. E. Latham, Revised medieval Latin word-list, 1965, s.v.). The penultimate letter c is so definite that the interpretation muria, ‘brine’ can be excluded.

48 Mr. G. S. Maxwell sent details, photograph and rubbing and proposed this reading. The fragment is broken across the foot of the second letter and no trace of any tail to form a Q survives.

49 Callender, M. H., Roman Amphorae (Oxford, 1965), 35.Google Scholar

50 See n. 45 (above).

51 Dr. Anne S. Robertson sent the sherd and details. Found with samian and coarse ware when Gartshore House was demolished; presented to the Hunterian Museum by the executors of the Gartshore estate.

52 Mr. L. P. Wenham delivered this for study. The item was unstratified on the floor of a second and third-century building; the site lies ¼ mile N. of Cataractonium town.

53 Mr. D. S. Neal sent this and nos. 47 and 51 (below) for the Ministry of Public Building and Works. The ditch preceded building A, of Antonine date. The second and third letters have extra cuts.

54 Mr. A. L. Pacitto directed the excavation for the Ministry of Public Building and Works, see JRS lviii (1968), 208, n. 18. Miss D. Charlesworth sent the vessel and full details.Google Scholar

55 Mr. H. P. Cooper sent the two sherds for study.

56 Mr. H. K. Bowes submitted the sherds for Mr. H. J. Coates on behalf of the Enfield Archaeological Society. Th e letters are boldly cut in capitals apart from a cursive form of R. Severitudo is a rare word found in Plautus, Epid. 5, 1, 3. and Apuleius, Metam. 1, 25. Gradenwitz, Laterculi has no other word to fit these letters.

57 See n. 39 (above).

58 See n. 53 (above).

59 Now in the Hunterian Museum, Glasgow. Dr. Anne S. Robertson made it accessible and gave details; the bowl is flat-rimmed and of Antonine I period. For the plan of the fort see J. Macdonald and J. Barbour, Birrens and its Antiquities (1897), pl. IA. For the excavation see p. 274 above.

60 Mr. S. G. Stanford sent the fragments. The fort is one mile NNE. of Kenchester (Magna), grid ref. SO 452445.

61 Dr. G. Webster sent details and the fragment. The diagonal stroke of N is only dotted.

62 See n. 53 (above).

63 Dr. K. Branigan sent details and a sketch of this and no. 53 (below). The sherd is worn. The site lies 3½ miles SE. of Chesham.

64 4 See n. 63 (above).

65 Information from Mr. G. C. Boon.

66 Information from Mr. K. S. Painter.

67 For this Museum Dr. R. Raper provided a set of photographs to help in identification.

68 Information from Dr. D. J. Smith.

69 JRS lviii (1968), 209, no. 30. Information from Mr. R. Hogg.Google Scholar

70 Prompted by E. Birley's suggestion in JRS lvi (1966), 228. Insert c(enturioni) in the transcript and ‘centurion’ in the translation; delete under 1. 5 the cross-reference to RIB 11.Google Scholar

- 6

- Cited by