Article contents

Fragments of a lorica segmentata in the hoard from Santon, Norfolk

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 09 November 2011

Abstract

- Type

- Notes

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © Mansel Spratling 1975. Exclusive Licence to Publish: The Society for the Promotion of Roman Studies

References

1 Despite the fact that R. R. Clarke pointed out forty years ago (Norfolk Arch, xxv (1933–1935), 206)Google Scholar that the hoard was found in Santon parish, Norfolk, between the east end of the former Half-Moon Plantation and the site of St. Helen's Oratory, at approximately TL 837873, it is still frequently referred to as the Santon Downham, Suffolk, hoard, as a result of the incorrect information given to Baron Hügel, A. von (Proc. Cambridge Antiq. Soc. ix (1894–1898), 430–1)Google Scholar, later followed by R. A. Smith in his study of the hoard (Proc. Cambridge Antiq. Soc. xiii (1908–1909), 146–63)Google Scholar. The Santon Downham attribution ought to be dropped if only to distinguish the present hoard from that of Icenian coins which was found in Santon Downham parish (for which see Allen, D. F.. Britannia i (1970), 19, 21).Google Scholar

2 Op. cit. (note 1). A full publication of the hoard is being prepared by the writer.

3 E.g. the steelyard and its travelling weight: Smith, op. cit. (note I), pl. xvi, No. 3.

4 E.g. the dolphin brooches, for which see below.

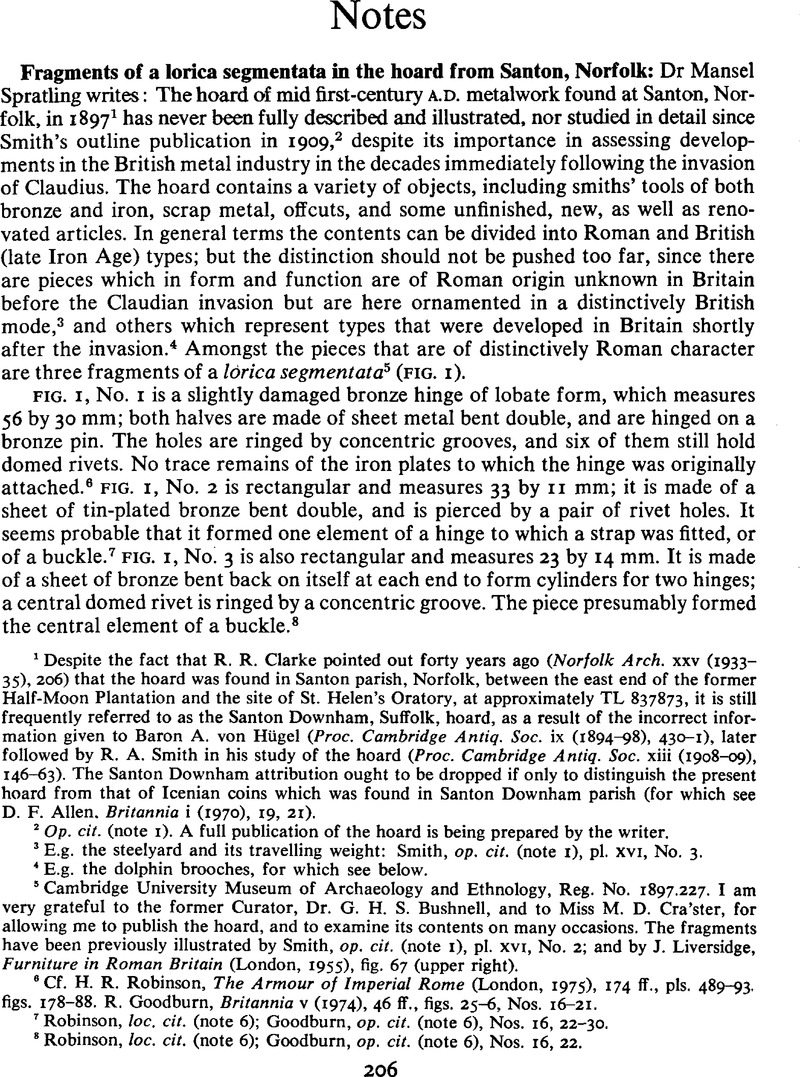

5 Cambridge University Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology, Reg. No. 1897.227. I am very grateful to the former Curator, Dr. G. H. S. Bushnell, and to Miss M. D. Cra'ster, for allowing me to publish the hoard, and to examine its contents on many occasions. The fragments have been previously illustrated by Smith, op. cit. (note 1), pl. xvi, No. 2; and by Liversidge, J., Furniture in Roman Britain (London, 1955), fig. 67 (upper right).Google Scholar

6 Cf. Robinson, H. R., The Armour of Imperial Rome (London, 1975), 174Google Scholar ff., pls. 489–93. figs. 178–88. Goodburn, R., Britannia v (1974), 46 ff., figs. 25–6, Nos. 16–21.Google Scholar

7 Robinson, loc. cit. (note 6); Goodburn, op. cit. (note 6), Nos. 16, 22–30.

8 Robinson, loc. cit. (note 6); Goodburn, op. cit. (note 6), Nos. 16, 22.

9 Cambridge University Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology, Reg. Nos. 1897. 224A-E and G-K. Only six of the brooches have been illustrated: Smith, op. cit. (note 1), 159–60, figs. 9–10; Fox, C., The Archaeology of the Cambridge Region (Cambridge, 1923), pl. XVIII, 5–8.Google Scholar

10 Cf. Hawkes, C. F. C. and Hull, M. R., Camulodunum (Oxford, 1947), 308 ff.Google Scholar

11 Webster, G. A., Britannia i (1970), 193, with references cited.Google Scholar

12 Ibid.

13 Manning, W. H.Britannia iii (1972), 232) was incorrect in claiming that ‘A date of c. A.D. 60 is generally accepted for its deposition, largely on the supposition that the group was concealed at the time of the Boudiccan revolt’; this has never before been argued in print.Google Scholar

14 As indicated by the distribution of Icenian coin-hoards: Allen, op. cit. (note 1), figs. 1–2.

- 3

- Cited by