Article contents

Abstract

Information

- Type

- Roman Britain in 2011

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © The Author(s) 2012. Published by The Society for the Promotion of Roman Studies

Footnotes

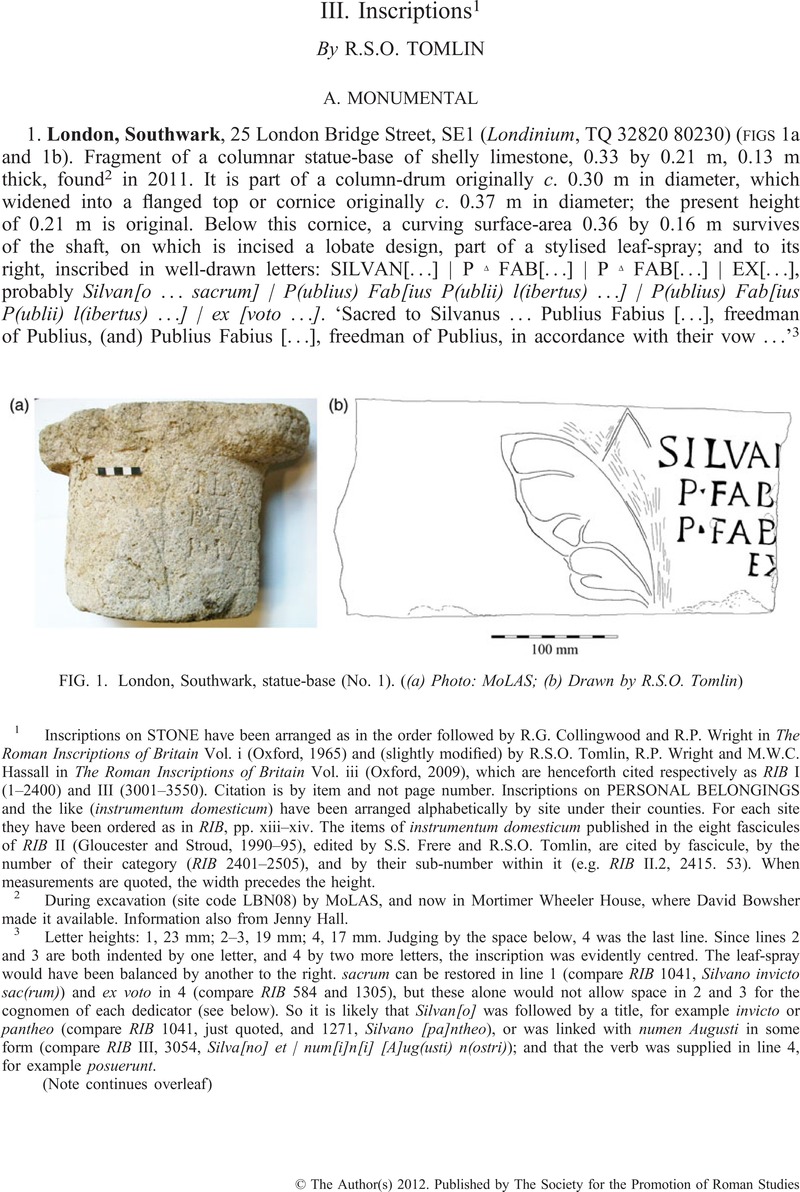

Inscriptions on STONE have been arranged as in the order followed by R.G. Collingwood and R.P. Wright in The Roman Inscriptions of Britain Vol. i (Oxford, 1965) and (slightly modified) by R.S.O. Tomlin, R.P. Wright and M.W.C. Hassall in The Roman Inscriptions of Britain Vol. iii (Oxford, 2009), which are henceforth cited respectively as RIB I (1–2400) and III (3001–3550). Citation is by item and not page number. Inscriptions on PERSONAL BELONGINGS and the like (instrumentum domesticum) have been arranged alphabetically by site under their counties. For each site they have been ordered as in RIB, pp. xiii–xiv. The items of instrumentum domesticum published in the eight fascicules of RIB II (Gloucester and Stroud, 1990–95), edited by S.S. Frere and R.S.O. Tomlin, are cited by fascicule, by the number of their category (RIB 2401–2505), and by their sub-number within it (e.g. RIB II.2, 2415. 53). When measurements are quoted, the width precedes the height.

References

2 During excavation (site code LBN08) by MoLAS, and now in Mortimer Wheeler House, where David Bowsher made it available. Information also from Jenny Hall.

3 Letter heights: 1, 23 mm; 2–3, 19 mm; 4, 17 mm. Judging by the space below, 4 was the last line. Since lines 2 and 3 are both indented by one letter, and 4 by two more letters, the inscription was evidently centred. The leaf-spray would have been balanced by another to the right. sacrum can be restored in line 1 (compare RIB 1041, Silvano invicto sac(rum)) and ex voto in 4 (compare RIB 584 and 1305), but these alone would not allow space in 2 and 3 for the cognomen of each dedicator (see below). So it is likely that Silvan[o] was followed by a title, for example invicto or pantheo (compare RIB 1041, just quoted, and 1271, Silvano [pa]ntheo), or was linked with numen Augusti in some form (compare RIB III, 3054, Silva[no] et | num[i]n[i] [A]ug(usti) n(ostri)); and that the verb was supplied in line 4, for example posuerunt.

(Note continues overleaf)

The dedicators in lines 2 and 3 bear the same praenomen and nomen; they might therefore be father and son, but they are much more likely to be freedmen of a Publius Fabius […], with P(ublii) l(ibertus) forming the middle part of their nomenclature; they would have been distinguished by their cognomina, now also lost.

This base supported a votive statue of Silvanus, a woodland god explicitly associated with hunting in RIB 1041, 1207 and 1905. His name was not necessarily preceded by deo: compare RIB 1041, 1271, and III, 3054, quoted above. After the stone figure of a hunter-god was discovered beneath Southwark Cathedral, Ralph Merrifield suggested that it came from a cult shrine near the road-junction south of London Bridge (‘The London hunter-god and his significance in the history of Londinium’, in Bird, J., Hassall, M. and Sheldon, H. (eds), Interpreting Roman London: Papers in Memory of Hugh Chapman (1996), 105–13, especially 108Google Scholar), noting two related figures from London. He discussed the cult in southern Britain, suggesting that the deity was Apollo Cunomaglos, to whom an altar (RIB III, 3053) is dedicated at Nettleton Shrub. However, this site also produced an altar to Silvanus (RIB III, 3054, quoted above), which suggests that Silvanus was an alternative identification (ibid., 110).

4 During excavation by the Kent Archaeological Rescue Unit, and now published by Brian Philp in The Discovery and Excavation of the Roman Saxon Shore Fort at Dover, Kent (2012), 111 with fig. 55, where he comments: ‘As it survives, it appears to be dedicated to the Mother Goddesses (DEAE) of the province of Britannia (BRITANI).’ The limestone is like that of RIB III, 3031 (Dover), an altar dedicated to the Matres Italicae by a st(rator) co[n(sularis)] to mark his building of a shrine (aedes). (Reference communicated by Martin Henig.)

5 This is the first instance from Britain of this dedication, but compare RIB 643, Britanniae sanctae; 2175, genio terrae Britannicae; 2195, Campestribus et Britanni(ae). The mis-spelling of Britannia is trivial and well-attested, but is previously unknown from Britain itself, since the Carlisle writing-tablet (RIB II.4, 2443.5) ‘addressed’ to someone IN BRITANIA must have originated from elsewhere. In Dover, a port of entry, this mis-spelling might suggest that the dedicator had just arrived from another province, but unfortunately his name and status have been lost.

6 With the next two items during excavation after the Cockermouth flood by Grampian Heritage and Training, directed by Frank Giecco of North Pennines Archaeology (Current Archaeology 255, 34–9, where this item is illustrated on p. 36). Ian Caruana made them available with his comments. Unlike the next two items, which consist of strongly bedded stone and are thus probably slabs, this item shows no bedding and is part of a block; it was an altar, to judge by the line-width (see next note).

7 In line 1, only the horizontal bottom stroke survives of the first letter, E or L; it is too wide to be the initial serif of M, a letter which is suggested by the converging diagonal strokes that follow, but to be rejected because there is no initial vertical stroke, and the second stroke of ‘V’ does not align with the vertical stroke which follows. PR therefore begins a new word, presumably praefectus (abbreviated). In line 3 there is trace of a triangular stop after PRAEF, followed by sufficient remains of the first diagonal of A. In line 4, only the curving top survives of the last letter (since followed by uninscribed space); thus it is C, G or S.

Just enough survives of lines 3 and 4 to identify the dedicator as prefect of ala I Tung(rorum), a cavalry regiment attested at Papcastle by six lead sealings ( Britannia 36 (2005), 487–9, nos 22–27Google Scholar) after it left the Antonine Wall (RIB 2140). There was an ala Moesica (but no cohors), but this cannot have been the previous or subsequent command of a praefectus alae, so MOESIC in line 2 must refer to the classis Flavia Moesica (however abbreviated), with PR in line 1 as the beginning of praef(ectus). Command of this fleet on the lower Danube was a sexagenary post senior to the command of an ala; for an example of this progression, see ILS 8851 with Devijver PME A21. The dedicator, before naming his present post, evidently cited his new appointment. LVI in line 1 probably concluded his formal nomenclature, his place of origin perhaps, for example [foro Fu]lvi (ILS 2261). On this reconstruction, the line-width can be calculated quite closely; leftward by the loss of I TVN in line 4, and rightward by the vertical coincidence of PR[AEF], MOESIC[AE] and A[LAE] in lines 1–3. There would have been 3–4 letters before PRAEF in line 3, corresponding to classis Flaviae above it in line 2, much abbreviated; perhaps an abbreviated dynastic title after Moesic[ae], for example Gordianae as in ILS 8851.

8 The surface is smoothed by wear, as if from re-use as a paving-stone. In line 1, a third letter is indicated by part of its bottom serif. The third letter in line 2 is more likely to be R than F or P since its middle stroke begins from the vertical stroke (contrast P) and trends upward. Perhaps […]i pr[aefecti], but there are other possibilities. The letters in line 3 are more slight, and the loop of D has been almost worn away; the space below suggests that this was the bottom line. A possible restoration is [IV]L or [VA]L PVD[ENS], the name [Iu]l(ius) or [Va]l(erius) Pud[ens].

9 The generously spaced M suggests a tombstone headed by D vacat M, but this is only a possibility. In line 2, ligatured VA is damaged, but the cross-bar of A survives; its second diagonal stroke seems to have met N.

10 During a five-year campaign of excavation, for which see Britannia 41 (2010), 361Google Scholar. Information from David Petts and David Mason, who sent a photograph. The fragment is at present in the Department of Archaeology, Durham University.

11 Line 1: the spacing suggests T before V, but first letter F or P would also be possible. In the edge there is apparently the beginning of a third letter, resembling the tail of S. Line 2: the letter after SAC is E reversed, i.e. ligatured; the slight rake of the vertical, and the apparent nick of a serif in the broken edge, suggest ER. Lines 3 and 4: enough survives to guarantee the formulation here of ‘[name of ala] cui praeest [name of commander] praefectus equitum’. Although cui praeest unabbreviated to C P is found in the third century (RIB 1914, 1983), it is more likely to be second-century, but in either case the cavalry unit would be the ala (Hispanorum) Vettonum c(ivium) R(omanorum) which is attested at Binchester by RIB 1028, 1032 and 1035 (all undated), and probably by 730 (from Bowes, the adjacent fort) in a.d. 197/8.

This is presumably a building inscription, which would have been headed by the name and titles of the emperor. It concluded with the names of the unit responsible and its commander, which would have been preceded by a reference to the governor. However, the sequence SACER cannot be accommodated to any known governor, and it is conceivable that a consular date was inserted, Tertullo et Sacerdote co(n)s(ulibus) (a.d. 158), the year in which RIB 1389 (see below, Addendum (d)) suggests that the Hadrianic frontier was being reconstructed.

12 During excavation by the Vindolanda Trust directed by Andrew Birley. Robin Birley made it available.

13 This ‘letter’ may only be zig-zag decoration, but it is not repeated on either side; if indeed a letter, then perhaps the initial of a god such as Mars or Mercury. For another schematic snake incised on a building stone, see RIB III, 3257 (with note).

14 With the next item during excavation by Chester Archaeological Society directed by David Mason. A minute sherd of samian (s.f. 234) was found in 2004, bearing part of a letter, perhaps C. They were made available by Margaret Ward.

15 The most likely name with this sequence is Maternus (compare the next item), but there are other possibilities.

16 In the backfill of well 1750, first excavated in 1893: see Fulford, M. and Clarke, A., Silchester: City in Transition. The Mid-Roman Occupation of Insula IX c AD 125–250/300. A Report on Excavations Undertaken Since 1997 (2011), 44–6Google Scholar. Information and comments from Peter Warry, who provided a drawing.

17 This stamp is previously unattested, but would seem to be a private tile-maker's like the two already found at Silchester, IVC DIGNI (RIB II.5, 2489.18(vii)) and L H S (ibid. 21C(ii)). Since A coheres with R, whereas F, L and O are separated, and since few nomina begin with AR, it is likely that AR incorporates V for Aur(elius). The cognomen would be Florus or Florentinus.

18 During excavation by Kent Archaeological Society, reported in successive volumes of Arch. Cant. For this item see Lyne, M., ‘The Roman villa at Minster in Thanet. Part 8: the pottery’, Arch. Cant. 131 (2011), 231–75Google Scholar, at 262–3, no. 37 with fig. 4.37. For an illiterate ‘star-shaped graffito’ on a coarseware dish, see ibid., 269–70, no. 84 with fig. 8.84. (References communicated by Sheppard Frere.)

19 This praenomen is often used as a cognomen, but a derived name is also possible; for example Sextilius, Sextinus, etc.

20 In the late fourth-century demolition layer, during excavation by Maidstone Area Archaeological Group. Information from A.J. Daniels and Dana Goodburn-Brown, who made it available.

21 A is sometimes ‘open’, sometimes written with a cross-bar. S is reversed. R occurs twice in (i) and four times in (ii), visually in a vertical sequence, and alternating from left to right; the tail probably indicates the direction of writing. The left margin of (ii) is irregular, as if it marked the ends of lines, not their beginning. ONERAT[VS] in particular seems to have been written from right to left. The crowding of letters towards the end of MEMORIAN[VS] and CONSTITV[S] suggests they were written from left to right, and space ran short. The space after CONSTAN(…) is apparently not inscribed, and A is written over T.

22 See previous note. It is not uncommon for ‘curse tablets’ to be written by reversing the letter-sequence in various ways, including the use of mirror-image letters, and the other tablet from Kent ( Britannia 17 (1986), 428, no. 2Google Scholar) is written ‘boustrophedon’ with alternate lines inverted, but there is no British parallel for the present format, which seems to be unsystematic. Since it is too elaborate to be due to error or incompetence (and note that CONSTAN(…) was corrected), it must have been intentional, whether to make the text more difficult to read and thus ‘secret’, or to ‘confuse’ the lives of the persons named (for which see Faraone, C.A. and Kropp, A., ‘Inversion, adversion and perversion as strategies in Latin curse-tablets’, in Gordon, R.L. and Simón, F. Marco (eds), Magical Practice in the Latin West (2010), 381–98)Google Scholar.

23 (i) ATINED[ is probably a transcription error for Celtic Atidenus (CIL xiii 8627). Sacratus (with a diagonal T) is well attested in Gaul, and although Latin (but not in Kajanto), is one of a group of cognomina which ‘conceal’ a particular Celtic name-element (e.g. RIB II.7, 2501.481, Sacra). Celtic Sacirus is also found in Gaul. Celtic Atrectus is well attested (e.g. Tab. Vindol. II, 182.14), but there are some Latin cognomina in -ectus. (ii) Cundac[us], unless the second C is actually G, is for *Cundagus (better *Cunodagus), which is not actually attested, but is composed of two Celtic name-elements. Cunoaritus is an elaboration of Cunoarus (attested as a British mortarium-maker; Frere, S.S., Britannia (1991), 204, n. 23Google Scholar). The other four names are Latin cognomina. Onerat[us] is rare, but see RIB III, 3108 (with note). Memorian[us] is also rare, but one of those derived from Memor (Kajanto, 255). For Constitutu[s] see Kajanto, 350, and perhaps Tab. Vindol. III, 814. Constan(…) was apparently not finished, but would be Constans or one of its derivatives. A is written over the second T, to correct a transcription error.

24 During a metal-detector survey in the excavation directed by Steve Willis as part of the Lincolnshire Wolds Project. Dr Willis made it available before cleaning and conservation, and it has been drawn, but a full transcript with commentary (preferably after re-examination) is reserved for his final report.

25 During excavation by MoLAS, for which see Britannia 40 (2009), 260Google Scholar. Amy Thorp made it available.

26 There is space after the third letter, followed by a sinuous curve which does not look like a letter-form; then four more letters. This is apparently a neuter plural, i.e. a commodity, not a personal name. So perhaps ΔIEΞOΔ(I)KA was intended, the double zigzag of Ξ being reduced to a double curve, and iota omitted by oversight. This would be the neuter plural of an adjective derived from διέξοδοϲ, used as a medical term for ‘evacuation’ [of the stomach] by Hippocrates (Prog. 11 (Alexanderson, 206.5), quoted also by Galen). The derived διεξοδικά would then mean ‘(agents) causing evacuation’, i.e. ‘purgatives’: this sense is not attested, but purging played a large part in ancient medical practice, and various effective agents were available.

The suggestion that this was a Roman apothecary's jar must remain uncertain, in view of the difficulties of reading and interpretation. But many Roman doctors, even in Britain, were Greek-speaking, which would explain why a good-quality vessel of British manufacture should have been quite carefully inscribed in Greek. The best parallel seems to be the small amphora from the Athenian agora which bore the graffito διουρ(ητικόν), ‘diuretic’ ( Lang, M., The Athenian Agora: Results of Excavations Conducted by the American School of Classical Studies at Athens, Vol. XXI, Graffiti and Dipinti (1976), 75Google Scholar, Hd 21), but in the West compare CIL iv 5738 (Pompeii), a jar with the painted inscription lomentum flos | ex lacte asinino Uticense (‘best-quality lotion from asses' milk of Utica’); also RIB II.6, 2494.94 (Carpow), an amphora with the graffito πράϲι[ον] (‘horehound’, a cough remedy); and the Haltern medicine-box lid inscribed ex radice Britanica (‘British Root’, Dock used as an antiscorbutic) ( Britannia 22 (1991), 143–6Google Scholar).

27 During excavation (site code FEU08) by MoLAS for Land Securities, directed by Robin Wroe-Brown and Gemma Stevenson. It is now at Mortimer Wheeler House, where Angela Wardle made it available and provided information. It belongs to the group of shallow convex bowls with Biblical, Christian, classical cult or hunting scenes, which includes the Wint Hill bowl (RIB II.2, 2419.45; J. Price and S. Cottam, Romano-British Glass Vessels: A Handbook (1998), 125, fig. 51a).

28 The differentiation in width between the two uprights of A shows that it was meant to be read through the glass, i.e. that it was inscribed on the underside of the bowl. It was therefore the last letter of the word which identified the scene, whether feminine singular or neuter plural.

29 During a watching-brief (site code JWR11) by MoLAS; Michael Marshall sent a photograph and full details. The form is dated by Price and Cottam, op. cit. (note 27), no. 14, to the third quarter of the first century a.d., and an almost complete stamped mortarium of a.d. 55–80 was also recovered.

30 D is incomplete, and might be a rectangular O, but the cognomen Burdo (‘mule’) is well attested (Kajanto, 326), especially as borne by a samian potter of Lezoux; the derived Burdonius occurs in Britain (RIB II.4, 2445.21). Two other sherds were also found, probably from the same cup but not conjoining; one preserves a gladiator's head, and above it the possible tip of a moulded letter, perhaps O or V. For other glass vessels naming gladiators in this way, see RIB II.2, 2419.22–35; but they do not include Burdo.

31 During excavation (site code CYQ05) by MoLAS directed by Ken Pitt, interspersed by a watching-brief. Information from Angela Ward, who provided a photograph.

32 With the next two items, in the same excavation as those noted in Britannia 42 (2011), 448, nos 10–12 Google Scholar. The graffiti were all made after firing, and thus identify the owners. Others too slight for inclusion here will be published in the final report: three initial letters of incomplete graffiti (B, P and Q), three literate fragments, and five ‘crosses’ of identification.

33 Above and to the right of A is the end of a diagonal stroke (drawn in outline), which is slighter in character; since Ianuarius is quite a common name, it is probably casual. Ianuarius is sometimes abbreviated to IAN, but not necessarily so here.

34 This large letter is now incomplete, but evidently stood on its own; the owner must have abbreviated his name to its initial letter. The letter K is rare in Latin, and is mostly used to replace initial C in words such as carus and (as in the Vindolanda Tablets) carissimus, and in personal names, notably Carus and its derivatives. Compare item No. 39 below, with note.

35 Although Vitalis is a common name, its bearer may be the same as VIT from the same site ( Britannia 42 (2011), 448, no. 10Google Scholar), also on samian but by another hand.

36 And reported under the Portable Antiquities Scheme: information from Jenny Hall and Richard Abdy. It has been donated to the Museum of London.

37 This is the first spintria to be found in Britain and, especially since it was found unstratified, we cannot be sure it was imported in the Roman period. The function of these tesserae is unknown, whether they were calculating jetons, or gaming counters, or even the ‘brothel tokens’ of modern legend. They have been dated by die-links to the reign of Tiberius. See Buttrey, T.V., ‘The spintriae as a historical source’, Numismatic Chronicle 7th ser. 13 (1973), 52–63 Google Scholar, where this item would be Scene 5 with numeral XIIII.

38 With the next three items during excavation by the Vindolanda Trust directed by Andrew Birley. Robin Birley made them available.

39 The potter's signature; it is the first instance from Britain of this Greek personal name frequent in the West. There is no sign of the inscribed date which sometimes accompanies Dressel 20 signatures.

40 The tail of R is crossed by two parallel scratches which seem to be casual. This is the owner's abbreviated name; perhaps one of the Germanic names beginning with Hari- (compare Tab. Vindol. III, 670.B.ii.6, ?Hario), or even Greek, the only British example being Hardalio (RIB 1436).

41 Only the lower parts of the crudely inscribed letters survive, including a bold S (?ligatured with V, now lost) which implies the end of a personal name. The traces are consistent with Claudius, but this is uncertain.

42 Apparently RIB II.4, 2460.50, which has already been found in the bath-house west of the fort.

43 In association with a coin of Claudius II Gothicus (a.d. 268–70), during excavation noted in Britannia 42 (2011), 367Google Scholar. Information from Stephen Yeates, who sent a drawing by Andrej Čelovský. The reading is by Jane Timby, who identified the fabric as Oxford reduced ware.

44 During excavation by Chichester District Archaeological Unit directed by James Kenny. They are now in Chichester Museum, where Mr Kenny made them available to Lynne Lancaster of Ohio University, who surveys hollow voussoir-tiles from Britain in Journal of Roman Archaeology, forthcoming. Information from Professor Lancaster, who notes that they are in the same fabric as the two from Westhampnett published as RIB II.5, 2491.84 (with Addendum (e) below) and 126.

45 Now in the Yorkshire Museum, where it was seen by Kay Hartley and Ian Rowlandson, who made it available. It is probably of early legionary manufacture.

46 The letters are of ‘capital’ form, except for P, which is completed by a short downward stroke, not a loop. This is the potter's signature, probably in the nominative case, but the genitive ‘(work) of …’ is also possible. Crispus and its derivative Crispinus are both common Latin cognomina.

47 Near the village by a metal-detectorist, and at present in the National Museum of Antiquities, Edinburgh (E: 07.05.2010), where Fraser Hunter made it available.

48 Assuming an uncia of 27.288 gm, four unciae would be 109.15 gm. The four 4-unciae weights in RIB II.1, 2412.74–77, weigh respectively [under 99.2 gm], 104.59 gm, 104.65 gm, and 109.39 gm.

49 By a metal-detectorist, and at present in the National Museum of Antiquities, Edinburgh (E: 12.10.2010), where Fraser Hunter made it available. At Tinwald just to the south (NY 003 813) in 2010, the same detectorist found a lead disc 23 mm in diameter, with central hole and moulded ‘milling’, which weighs 53.74 gm. This is almost two unciae (54.58 gm), but there is no inscription.

50 The weight is just over one libra (327.45 gm) of twelve unciae. VIII (‘8’) cannot refer to the number of unciae (12), but is perhaps an error for XII. It is hardly a note of the number of scripula (each of 1.137 gm) by which it was overweight, since such precision would be unparalleled.

51 With the next fourteen items, and the two stone altars noted last year ( Britannia 42 (2011), 441, no. 5 and 443, no. 6Google Scholar), during excavation for East Lothian Council by AOC Archaeology directed by John Gooder. Sue Anderson made them available. All graffiti were made after firing, and thus relate to ownership of the vessel. Each is identified by a small find number (in brackets). Not included are nine other samian sherds with possible trace of literate graffiti, and twelve with marks of identification (a ‘star’ or ‘cross’), but the whole assemblage will be published in the final report edited by Fraser Hunter. This will include drawings of items 39, 40, 43 and 45.

52 Notes of capacity for Dressel 20 are quite often found here, but ‘one m(odius)’ would be much too low; see next note.

53 Notes of capacity for Dressel 20 mostly range from seven to eight modii, with or without a fraction: see RIB II.6, 2494, and the note on p. 33. One modius was equivalent to 8.754 litres, and contained 16 sextarii.

54 The first two letters are incomplete, but their remains are almost identical, consisting of a diagonal foot curving at the end; this suggests a rather angular C. Since there is just enough space to the left to see them as the beginning of the graffito, it seems that the initial letter was written twice. The third letter has also lost its top, but can be read as a rather narrow A. This reading CCA is confirmed by the sequence which follows: Candidus is a common cognomen. Only the bottom survives of the final letter, which is either A or I. Although Candidi (genitive) is the most likely reading, Candida (feminine) and even Candidi[anus] are possible.

55 The owner's name, abbreviated to its first two letters. There are many possibilities, the most likely being Celer, Celsus, Censorinus, Cerialis and Certus. The next item (G12) may be another version of this abbreviation.

56 The second letter is apparently C overlying a vertical stroke, not a reversed D. Almost no names begin with Ec-, and those which do are very rare, so EC is unlikely to be an abbreviated name. But since E with its exaggeratedly long vertical resembles that in the previous item (P15), and may be by the same hand, the graffito may represent the same name.

57 D is only a small triangle, scratched perhaps under cursive influence, but more likely to be sub-literate. The omission of L may be an error due to confusing L with V, both letters being made with the first stroke angled into the second. Final S is incomplete. To the left of this graffito is part of another, now illegible, which was probably the name of another owner. The name Decibalus, also written Decebalus, is the most frequent Dacian personal name, famously that of the last king of Dacia. Dan Dana, whose Onomasticon Thracicum (in preparation) will supersede D. Detschew, Die thrakischen Sprachreste (1957), has collected 25 instances; in Britain they are RIB 1920 (Birdoswald), RIB II.7, 2501.156 and probably II.8, 2503.242 (Densibalus).

58 Dan Dana (see previous note) comments that Drigissa is also a Dacian personal name, there being three instances already cited by Detschew. Although Decibalus is attested at Birdoswald (RIB 1920), where cohors I Aelia Dacorum was stationed, Dacians did not necessarily serve in ethnic Dacian units: a military diploma of a.d. 127 (RMD IV, 240) was issued to a Dacian who served in cohors II Lingonum in Britain, and four of a.d. 178 (RMD III, 184; IV, 293 and 294; ZPE 162 (2007), 227–31) were likewise issued to Dacians in non-Dacian units, who would have been contemporaries of Decibalus and Drigissa.

59 The graffito is complete, except for the tips of some letters, and there is no reason to doubt the reading. F is made in cursive fashion with a hooked second stroke, set too high for it to be read as K. A is also of cursive form. But the name Fradegus or Fradegius is unattested and of unknown etymology; there seem to be no Dacian/Thracian, Celtic or Germanic analogues.

60 The medial point makes it clear that the owner had two names (in the genitive case here), if not also an abbreviated praenomen now lost. There are other nomina ending in ulius, but the imperial nomen Iulius is so common that its restoration is probable. Only the (incomplete) first stroke of A survives, but its angle in relation to L and especially to the the foot-ring excludes the reading of I. The most likely cognomina are Laetus and Latinus, but there are many other possibilities. Since the owner was a Roman citizen, he is more likely to have been a legionary soldier than an auxiliary, especially since a legionary centurion is attested at Inveresk ( Britannia 42 (2011), 441–4, nos 5 and 6Google Scholar).

61 Ka[t]i could also be restored, but the name Karus is more common. Both are quite often written with initial K for C: see RIB II.7, 2501.281, 282 and 283.

62 P is broken towards the foot by the edge of the sherd, which makes it uncertain whether it originally stood alone (for a name abbreviated to its initial letter), but since it was placed close against the foot-ring and aligned with the diameter of the foot-ring, it was probably the first letter of a name P[…] written across the width. The broken edge runs diagonally, so the letter A, for example, might have been written quite close to P.

63 P is made with an incomplete loop, and only the first apex of M survives before the break, but the name Primus (and its derivatives such as Primitivus) are so common that the reading is sufficiently certain. There is no knowing whether it was written in the nominative or genitive case.

64 This might be the initials of a Roman citizen's tria nomina, but is much more likely (especially in view of the reduced V) to be an abbreviated name. The most likely is the praenomen Publius, often used as a cognomen, but also possible is a name derived from it, for example Publianus, Publilius and Publicius. Compare the next item (G19).

65 Compare the previous item (P11).

66 The third and fourth letters are reasonably certain, the two apices of M followed by the loop of P. Simplex is quite a common name: in Britain, it occurs at York (RIB 690), Maryport (860), Carrawburgh (1546) and Kirkby Thore (RIB II.7, 2501.518).

67 For this graffito on samian, see RIB II.7, 2501.542, 543 and 544.

68 ‘VILBIAM (RIB 154): kidnap or robbery?’, Britannia 37 (2006), 363–7CrossRefGoogle Scholar.

69 Hayward, K.M.J., ‘A geological link between the Facilis monument at Colchester and first-century army tombstones from the Rhineland frontier’, Britannia 37 (2006), 359–63CrossRefGoogle Scholar.

70 His son made it available to Francis Drake, who published it in his Eboracum (1736), 56, pl. VIII.3, which is cited by RCHM Eburacum, but not by RIB. Drake says it was ‘taken from the original’, but does not date it; however, it was surely earlier than Lister's transcript, since the altar was found in 1638 at Fairfax House, York, the seat of Thomas Fairfax (1560–1640), the father of Brian, from which it was transferred much later to the house of the first Duke of Buckingham (1648–1721), who married Thomas' granddaughter; according to Wellbeloved, C., Eburacum, or York under the Romans (1842), 87–8Google Scholar, it was here that Lister saw it.

71 In his Letters and divers other mixt Discourses in Natural Philosophy (1683), 115–16 with figure, which is not cited by RIB or RCHM Eburacum; instead, they cite the letter's first appearance in Phil. Coll. iv (1682). Lister's correspondence is now being edited for publication by Anna Marie Roos, who brought his manuscript to attention and provided fig. 37.

72 There is still just enough of the original surface at the bottom right-hand corner, although Wright does not show it in his drawing for RIB, to confirm that line 9 ended with D enclosing the middle cross-bar of E, i.e. ligatured DE.

73 RCHM Eburacum interprets the letter as a mis-read leaf-stop, but this is visually less likely. It is required by their reading of ac (see next note), but that too is unlikely.

74 RCHM Eburacum conjectures AC for ‘NC’, but this does not account for the third diagonal of Lister's ‘N’.

75 This expansion is conjectural since, although an altar is sacra in RIB 725, an ara augusta is unparalleled in Britain, and apparently elsewhere; it does occur in ILS 3090 (Rome), but the allusion is to Augustus. RIB notes (after Birley) that a P(ublius) Aelius Marcianus is attested as praef(ectus) coh(ortis) I Augustae Bracarum in ILS 2738, so that line 9 may conceal the abbreviated title of this unit; the question is discussed by Jarrett in Britannia 25 (1994), 56–7Google Scholar, who notes that military diplomas attest a cohors III Bracaraugustanorum in Britain. The numeral is different, but it may be added that prefects (or tribunes) of a cohort almost always specify their cohort; the few exceptions, in Britain at least, always come from the fort where the cohort was stationed, and even then it is usually named elsewhere in the text. But Fairfax and Lister seem to have been careful and independent observers, and it is difficult to suppose they both made the same error. Perhaps Marcianus, by dedicating this altar at York to celebrate his continued good health, implies that his posting had now ended and that he was on his way home; thus he might have recorded his rank, but not his post, since this was now occupied by another.

76 Hodgson, N., ‘The provenance of RIB 1389 and the rebuilding of Hadrian's Wall in AD 158’, Antiq. Journ. 91 (2011), 59–71 Google Scholar, at 63, fig. 3. His tentative suggestion (63, n. 9) that SF, which Wright thought were the initials of the centurion reponsible, might instead be an abbreviation for signifer is not supported by ILS 2198 (Rome), since a new fragment has shown that it reads BF, b(ene)f(iciario) ( Speidel, M.P., Die Denkmäler der Kaiserreiter: equites singulares Augusti (1994), 307, no. 559Google Scholar).

77 As Collingwood suspected (in JRS 26 (1936), 266, no. 7a), but did not substantiate. It can be seen that the tile-maker finished his graffito with two horizontal lines; the slighter line which subsequently cut them is casual. Lynne Lancaster (see above, No. 27) sent a photograph.

78 op. cit. (note 4), 112, citing ILS 2735 (Camerinum), which names him as M. Maenius C.f. Cor(nelia) Agrippa L. Tusidius Campester. For his nomenclature and career, see Birley, A.R., The Roman Government of Britain (2005), 307–9CrossRefGoogle Scholar.

Unfortunately the Dover fragment is only known from a rubbing, so it is not possible to check whether there was trace of E before the reduced S in the second line; but if there was, it would exclude the restoration of st[rator consularis] (abbreviated) preferred by RIB, and explain why S was reduced: presumably to fit Campester into a limited space. This is an attractive idea, but open to the objection that the prefect would have used only the names M. Maenius Agrippa, as he did on all four of his altars at Maryport (RIB 823–6).

- 3

- Cited by