The Chairman (Mr C. S. Begley, F.I.A.): I am delighted to introduce our first speaker who is Ian Collier. Ian is chair of the Cashless Society Working Party. He has been a fellow of the Institute and Faculty of Actuaries since 1977. He is now in retirement and is an active volunteer at the Institute and Faculty of Actuaries. His professional work experience was in life insurance, investment banking, and capital markets.

Mr I. C. Collier, F.I.A.: I would like to mention the authors of the paper who cannot be with us this evening. Justin Chan lives and works in Singapore and Sheila Nardani is nursing a newly born baby. They both send their regards. Samuel Achord will be speaking about negative interest rate policies, and Sabrina Rochemont will be talking mostly about the cashless world in motion, where we look at what is happening around the world. Sabrina is not a member of the Institute and Faculty of Actuaries, and so I would like to thank her specifically for the time, and the enormous effort, that she has put into the proceedings and the paper.

The paper was designed to be as neutral as possible. It examines the benefits, the risks, and issues across all the different stakeholder groups and across economies in different stages of development. Each and every one of them has a different answer. I would first like to make a few short definitions, which we have made in the simplest possible fashion. We define, for the sake of this paper, a cashless society as one without notes and coins. We talk about decashing, and decashing is the process of reducing the amount of notes and coins used within an economy. We also talked a lot about digital currencies. There are many different definitions of what is a digital currency, but for the sake of our paper we have called it a cryptocurrency, which is effectively electronic money with a Blockchain element.

What have we learned? Well, in section 7 of our paper, we do a SWOT analysis. I mentioned the different stakeholder groups. We have used the stakeholder groups as being the public, non-financial businesses, governments and central banks, commercial banks, and the payment ecosystem. All of them have totally different benefits, risks, and issues, and there is not one solution for any one of them. The demands and the desires to go cashless are different for them all. We have also learned that decashing is happening, and it is happening at a different pace around the world, but what we do not believe is going to happen is that the process is going to start reversing. We are going to enter into phase 2 of our paper almost straight after this sessional meeting, and we could not delay the publication of this paper because things are happening so rapidly across the world that it would have been really unconstructive to delay it. Some articles that we read can be out of date within 12 months.

In section 3, we talk about the benefits of a cashless society. Now, the cost of handling cash is enormous, and it varies as a percentage of GDP across the world. So, for example, the best estimates in the Western World are as much as half a percent of GDP. In India, for example, the numbers quoted (and these are very difficult to substantiate) could be as high as 3% of GDP. That is just handling cash. We are looking at the reduction in tax evasion that could emanate from a cashless society. Reduction in crime, corruption, illegal immigration, benefit fraud, modern-day slavery; these are issues which a cashless society could certainly help tackle. We talk about how a cashless society could even give us other options.

The taxation system could be totally revolutionised, and we talk about an automated payment transaction tax, which is a levy on all transactions, which can only be done in a cashless society. Sam (Achord) is going to talk about negative interest rates, which becomes most possible in a cashless society. But, although there are benefits, there are also risks and issues. In section 6, we have identified no fewer (and there are probably more) than 20 risks and issues. Each of them is different, each of them results in a debate in their own right, and we will come back to a number of them in phase 2 of our research.

However, of the risks and issues that we have come across, the one, I think, that worries the working party the greatest is risk 13 in section 6, i.e. what might happen in a totalitarian government. There is no doubt that for good or bad, cash provides a certain amount of obliqueness. The wrong type of totalitarian government could control dissidents very easily by just denying them the ability to open bank accounts. Again, we will be returning to that in phase 2, and look for solutions to that particular problem.

In section 5, we look at financial exclusion. It is a hot topic for some of the pressure groups looking particularly at age-related organisations, but also in parliamentary select committees. We know, and they know, that decashing in some societies, certainly in the UK, is happening already, and it is happening by stealth i.e. it is not being planned, it is just happening. This can cause a great deal of problems for the unbanked, the technically naive, and maybe some elderly people. We understand that, and we notice that there is a problem. Bank branches are closing. Should the state have a duty to provide a cash alternative if the clearing banks find providing cash commercially unviable? How would you transition to a cashless society? Transition management is something else which we will come back to in phase 2.

In section 5, we also look at the financial inclusion and exclusion of decashing in countries in different stages of their economic development. We find that it is very different for each of those different types of economy. If cash were taken away from an economy, would there be sufficient numbers of people, rightly or wrongly, that would like to replace it? For example, could you see dollars or euros floating around instead of £1 notes, £1 coins, or £20 notes, or whatever? We think barter and exchange of items for worth are less efficient, so digital currencies could now come in, and we all know about Bitcoin, but that is just one of a number of different possibilities for digital currencies. How would displacement towards alternative forms of payment outside the Bank of England control, or let us say Central Bank control. How would that affect financial stability in a country if it could not even control the currency being used within its own economy? Could digital currencies usurp the use of any Central Bank’s own currency? We will be looking at that under phase 2. How could a Central Bank control that? Is it likely that the Central Bank will issue its own digital currency?

We know that the Bank of England has conducted a proof of concept. What we do not know, necessarily, is what the answer is. If the Bank of England did introduce a digital currency, what would that mean for the entire banking ecosystem? It could totally disintermediate the commercial banks and their function. Again, we will be coming back to that in phase 2.

Could digital currencies revolutionise capital markets? Now, many of us might think of money as a series of loans. So, on the £20 notes you have in your pocket it says, “I promise to pay the bearer”: it is an IOU from the Bank of England. If you have £20 deposited at HSBC, all you have done is lent HSBC some money.

So, if a large corporate, let us say Apple, for example, wanted to come to the Stock Exchange, and wanted to raise money in lieu of an IPO, in lieu of selling equity, maybe, or in lieu of issuing debt bonds, for example, could they issue their own digital currency? That currency would be traded, not on the Stock Exchange, like their shares or bonds, but traded on an FX market. Instead, if you wanted to get liquidity out of the assets you hold, you would have to sell it on the Stock Exchange. But you could trade it, and it is spendable at stores anywhere. So, the whole prospect of the capital markets could be totally disintermediated by digital currencies. Is that around the corner? No, the answer is probably not. Is it going to happen? I do not know, but it could do, and it is something that, if it does not happen here, might happen somewhere else, and if we believe that the UK has an advantage in capital market transactions, if somebody else comes up with a totally different idea which suddenly usurps that idea, I think we need to be at least in control.

The Chairman: Thank you, Ian. Our second speaker is Samuel Achord. Sam is a senior actuary with Nordea Life & Pensions in Copenhagen. Prior to Nordea, he worked as a reinsurance pricing actuary with RGA in London. Sam is a fellow of the Institute and Faculty of Actuaries and a chartered enterprise risk management actuary. He is an active volunteer, recently contributing to working groups on equity release, and use of economic modelling within the profession.

Mr S. Achord, F.I.A.: For better or worse, every question answered in our paper seems to have raised three new questions. So, we did not solve anything. We know more, but we also know that we know a lot less than we should know. So, in that spirit, we will raise some questions that will hopefully foster debate on negative interest rates, starting with: “What are negative interest rates?” They may be the main driver for going cashless.

The economy is a complex, adaptive, dynamic, real-world system. As an actuary, you would like to be able to represent the economy as a cash flow system, with rules. That is what we do, and that is what we are good at. The problem is the flows, rules and constraints are uncertain or unknown, and the players are adaptive. Sometimes, the players even change the rules. It is a lot more complicated than a life insurance policy. There is enough information, misinformation, fake news, and opinion to be able to develop and support any viewpoint you want. On every issue, there are ten viewpoints, and they are not all wrong. They are not all right, but it is difficult to tell who is right. It is a question of is it correct? Is it likely to be accurate? Is it likely to be incorrect?

For those of us who follow the actuaries code, it raises an issue. Any communication should be accurate and not misleading, but the complex interconnected nature of the areas of uncertainty in economics makes it improbable to communicate the potential effects thereof in an accurate and not misleading way.

There is a very high likelihood that retrospectively it will have been incorrect. Before we get to the discussion on that, here is a preface to negative interest rate policy (NIRP). It is important to understand the global economy as a system, and the relationships among wealth, money, and currency, and the options we might consider in times of emergency. NIRP, price targeting, elimination of physical cash, stock exchange closures, asset freezes, and the list goes on. You cannot understand the mechanics of the US dollar looking at the USA in isolation. On the other hand, you cannot understand the mechanics of another nation’s economy without considering the effects and interrelationships with the US dollar.

So, the question is: “Why am I mentioning the US dollar?” First, the US dollar is the de facto reserve currency across most of the world, and some people think that is in jeopardy. A lot of people do not.

Second, why is the United States pushing for a cashless world? Why are governments across the world pushing to remove cash? Why are big multi-nationals pushing to remove cash?

Third, although it is an impossible problem, if you understood all of the problems, risk constraints, and issues related to physical cash and to electronic cash, then you might be able to understand the impetus behind the push to remove cash. That is why we should view it as a system, and the US dollar is a big part of this system. Banks and debt are central to the economy. With positive nominal interest rates, one plus the interest rate (R) is needed for all borrowers to repay all loans next year. If it is not there, then somebody has to default. So, where does this money come from? It comes from other borrowers. So does stability equal stable, nominal profit, equal a gradual increase in the money supply?

Alternatively, with negative nominal interest rates, one minus R is needed for all borrowers to repay all loans next year. So, where does the money go? Does it go to other borrowers? We are not used to, and not comfortable with, the destruction or the deletion of money. We are very used to the creation of money via debt and loans, and such, and the cancellation thereof as it is repaid. But to have money cancelled seems very counterintuitive or impossible. So, in the case of negative, nominal interest rates, does stability equal nominal profit, equal a gradual decrease in the money supply? If it does, we have missed something. Finally, when discussing NIRP, we need to consider that banks and debt are central to the economy. Banking jargon restricts the resolution of banking problems to bankers. NIRP, is it a boon to borrowers and a burden to savers? Banks on one side, life insurers and pension schemes on the other hand, are on opposite ends of the maturity transformation.

Similarly, in terms of leverage, life insurers and pension schemes are on the unleveraged end of the spectrum, if you look at who is playing in the market. That is a good thing if you are a very long-term player. Large amounts of leverage over the very long-term will get you in trouble. The banks seem to get a lot of help from Central Banks. The question is, is banking hard? The help that banks have received since the financial crisis seems to have come at a cost to long-term savings, and pensions, and long-term insurance products.

Risk itself does not disappear, so is macro risk increasing or decreasing? Is that reflected in the aggregate balance sheet? If not, where is it escaping to? Where is it accumulating? This is like the sub-prime crisis, which was where risk accumulated. Is risk growing today unnecessarily and if so where is it hiding? Negative interest rates, reinvestment in long-term investment in insurance products are they less viable today than they have been in the past? Is NIRP here to stay? Is it avoidable? Is it unavoidable?

So, those are just some ideas for our discussion on NIRP, and I hope you will all contribute even though NIRP is just a tiny part of the whole cashless paper.

The Chairman: Thank you, Sam. Our third and final speaker in the sessional presentation is Sabrina Rochemont. Sabrina works for a global organisation in the UK as an IT service management consultant. She is a specialist in service transition, with interests in cloud computing, project management, business, and economics. She joined the working party in January of last year.

Ms S. Rochemont: Throughout 2017, we closely followed the international news on the cashless society. The result is a chronicle of events that we called, “A Cashless World in Motion.” The second semester of 2017 will soon be available as an addendum on the working party website. So, what are the key takeaways? The speed of uptake in new payment technologies seems closely related to the unmet demand for financial services. In developed countries, we see a gradual rise in cashless transactions, but contactless payments seem to be eating away at low-value transactions; the ground, normally, of cash takes. We may be sleepwalking into a cashless society, but are we excluding the vulnerable in the process?

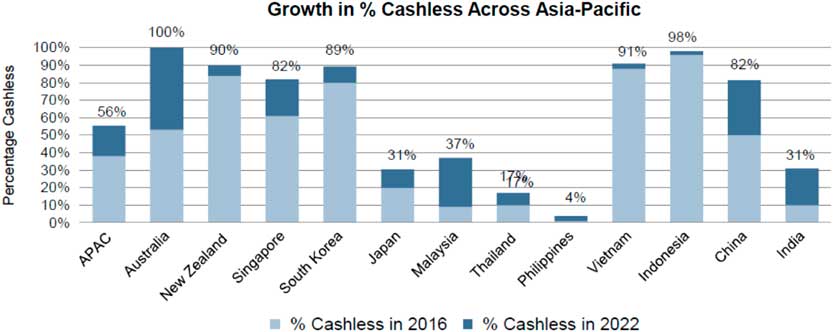

Ten years ago, M-Pesa (a mobile phone-based money transfer service) kicked off a revolution in Africa and surrounding countries where most people banked. Ten years on, the level of ecosystem moves has been absolutely breath-taking. That would be worthy of a separate presentation, but we will focus on the Asia-Pacific region (Figure 1).

Figure 1 Asia-Pacific regionNote: Percentages are based on volume with exception of Vietnam and Thailand which is based on value.

Here, you see a novel picture, with different levels of development towards cashless transactions in Asia Pacific.

In addition, we have noted some activity in some additional countries like Bangladesh, Pakistan, and Sir Lanka. Also, Cambodia would deserve its own study because it has just celebrated the nine-year anniversary of the launch of its own mobile banking provider. So, it would be good to see the results there. Amongst these countries, a study has classified Australia and New Zealand as in the leader group of most digitally advanced countries i.e. the countries where you are least likely to use cash. Closely behind, some other countries like China, Malaysia, Thailand, and Vietnam are assumed to be actively moving towards a cashless society, albeit with really different timescales. Some of these prefer mobile payments, such as China, Malaysia, and South Korea, but others such as Australia, Japan, and the Philippines, prefer card payment. Regardless of the payment technology that is preferred, there is a common theme across the region in that the cost of cashless transactions is such a concern that some countries are actively working to reduce these costs, and some, such as India, Malaysia, and Indonesia are subsidising low level, low-value transactions now, which is a breakthrough, to sustain the level of rise.

Speaking of which, on 8 November 2016, India announced demonetisation of 86% of its bank notes overnight. That led to immediate confusion, and total disruption of usual economic activities. On 1 July, it implemented a goods and services tax, which is equivalent to our VAT. So, a year on, how is India faring? Well, it all depends on your perspective really, so we have attempted to provide you with a bit of an overview. You will find the details of this in the addendum, in six categories.

Supporters hail the move as a strategic structural change that was really required in the economy, an economy that really needed formalising with an increase of the tax base. All of these changes are required for the long-term. Now, it is acknowledged that the negative impact was initially quite material. However, some benefits are already materialising, such as more sustainable inflation rates, dropping lending rates, and an increase in qualified technology jobs.

So, following the investments in biometrics systems and ID cards, and a united payments interface, what we see is an uptake in the use of banking facilities that is also enabling not only financial inclusion in the pure sense but also the cascade of, and better reach of, social funds. That is quite an interesting aspect of the change. The move was popular at home and abroad, but it certainly was not popular with the criminal class. One of the key reasons for a surprise announcement that night on 8 November was to disrupt criminal activities such as counterfeiting, terrorism, and money laundering. So, that was a key point that is also a pain point for detractors. Opponents are very upset by the lack of consultation on the engagement, not only for the decision but also for the implementation, and how the economy was handled following the announcement. The government continued to have a one-sided decision-making process. The key criticism is around the liquidity crisis that ensued, which led to major social disruption, loss of jobs, and people being confused, especially in rural areas.

Months on, the decision is still viewed as a failure, as some figures put forward that the level of cash transaction was at the same level as broadly before de-monetisation, especially in rural areas where lack of infrastructure just does not enable such an uptake of cashless transactions. So, more work to do here. Detractors also doubt on the long-term benefits, clearly not quite seeing the long-term aspect, especially around the claims on the fight against crime, money laundering, and corruption. Security is also an issue, because of the level and the impact of cyber attacks. So, overall, there is some doubt over the outcome right now. We do not have enough hindsight yet, possibly because there is an insufficient level of economic figures yet available, and many can be disputed or counteracted.

So, we learnt a great deal about the cashless society in 2017, spurred on by mediatic events in India. We also discovered some initiatives that may be relevant in countries such as the UK and some examples include inclusive payments systems from Africa and also the cashless welfare card from Australia. Some early initiatives that were taken up in Sweden, were also implemented in France, to counter VAT fraud at cash registers.

The Chairman: Thank you, Sabrina. So, to open the discussion and debate part of this sessional event, we have Parit Jakhria. Parit is responsible for long-term investment strategy at Prudential Portfolio Management Group, which includes strategic asset allocation for a number of multi-asset funds’ long-term investment and hedging strategy, and providing advice on ALM strategy. He is also responsible for providing long-term economic views to Prudential group, as well as the development and maintenance of Prudential’s in-house stochastic assumptions system. Parit joined Prudential Portfolio Management Group in 2007 as Director of Quantitative Research, and his team responsibilities have evolved to include Strategic Asset Allocation, Capital Market Assumptions and Hedging Strategies. In 2014, Parit was appointed the head of the newly formed Long-Term Investment Strategy Function.

Prior to joining PPMG, Parit undertook a variety of roles within the Prudential Group across Risk, Capital Finance, Statistical Modelling, and Research. He is a fellow of the Institute and Faculty of Actuaries, as well as a CFA Charter holder. He has been an active member of numerous working parties for the Actuarial profession, including chairing the Extreme Events working party, and has contributed on a number of papers, articles, and presentations for the Actuarial Profession. He is a member of the Finance and Investment Board and Chair of the Finance and Investment Research Sub-Committee.

Mr P. C. Jakhria, F.I.A. (opening the discussion): I just wanted to say thank you very much to all the authors. It is an excellent paper and having read it more than once it was a really good read. I must say also, this is an opportune time in having the discussion in an open forum, because as you said, this is just a phase, prior to phase 2 of the research, and hence for any questions you have on the floor, there is a good chance they will fall into the research streams. It is going to be difficult to try and summarise the key features of the paper in a very short time. I will tell you some of the key points and takeaways I got from reading it.

I think, first, in the world we live in today, we have a series of developments which you would not have imagined, maybe 10, 15 years ago. The foremost in my mind is interest rates, and in particular negative interest rates. So in economics, you are taught to believe that positive interest rates are a must have in order to incentivise the deferral of consumption.

So, as human beings, we have a choice whether we consume now, or we wait and save to consume for the future, on the basis that there will be more items in the future. Clearly that has been turned on its head, and one factor, although not directly linked to cashless society, is very much indirectly linked in terms of the predominance of cashless society, making negative interest rates even more possible, and that is going to be one of my questions for phase 2. The work that was done initially on the NIRP: I found that fascinating.

In terms of the paper itself, I would very much recommend reading, if you have a choice of sections, the costs and benefits of being a cashless society, as well as the global case studies of various areas. The costs and benefits, in particular, were staggering. I had not expected such a large proportion of GDP to be a cost of cash in society. I suspect it is different in different economies, and perhaps one area for future travel might be looking at the costs of a cashless society as well. So, I think, within the UK, small businesses need to pay up to a 2% transaction fee, for all major card providers, which currently incentivises them to accept cash payments rather than card payments.

Are we, perversely, behind some of the fascinating case studies we saw in Africa? In particular, Kenya and South Africa, where the prevailing banking and finance systems have skipped two or three generations of technology to go straight into mobile banking with the invention and adoption of M-Pesa. The other fascinating thing in the paper was the global perspective, and the case studies of how different economies are going in the direction of cashless. There was a big public debate on the demonetisation in India, and it was fascinating to hear your take on it. The recent trends in Asia, in particular the move towards online retail, look like a big factor in the adoption of cashless and on the other hand, I feel that there may be some other areas, for example Japan, where there seems to be a slightly different direction which is not quite cashless. So, that is certainly worth investigating.

Other than that, I wanted to give an opening question to the speakers, and it is one that I really could not quite get my head round, and which is what I alluded to at the start. It was, if a cashless society increases the chances of negative interest rates, what do negative interest rates mean to the economics of society? How do you consider consumption and deferral of consumption in a world where there are negative interest rates as a consumer?

Mr Achord: As with, I think, a lot of the questions on American economics, it is a very difficult question. I think the main hurdle is the nominal zero of the P&L. You cannot make a profit if everyone is making a loss. If the whole world is shrinking, and we are at a point where productivity is decreasing or output is decreasing and GDP is decreasing, then on average, everyone will be making a loss. So, if you use an index, which seems very odd, then you would have profits relative to a negative number, which might address the issue of not deferring consumption, as you said. That is only one aspect, and I am sure there are other equally valid and better responses to that question.

Mr Jakhria: Thank you very much, and I guess we will be delighted to open up the floor to questions.

Mr R. J. Houlston, F.I.A.: I would like to thank the authors and other contributors to this paper for the information that they have managed to bring together. However, I am not sure I come out much wiser as a consequence. There seem to be far too many anomalies for this thing to make sense. In the conclusion sections, the authors appear to have resigned themselves to the idea that we will move to a so-called cashless world. I believe that, in the public interest, the Actuarial profession should seek to contribute to the debate rather than document and help manage the implementation. Of course, I can understand wider issues may not have been within the scope of the working party, but perhaps the finance and investment board might like to consider the scope again, after taking into account discussions at this meeting. I think the most important word in this paper is in its title, and that is “Society.” My interpretation of this is, that we all collectively have an interest in how much money, and specifically in this case, so-called cash, is organised.

Cash and society are closely linked, and it is cash which enabled the world many of us now take for granted. Playing with this cash could be dangerous. Obviously, there are many forms of political structure that allow individuals to have a voice, but I believe there has to be an explicit choice. I dislike the idea that society could be considered to have accepted something, because it is made convenient for them to change their habits. One of my key issues was, we are talking about a society without notes and coins, which I think is a very important point. I believe that a lot of your anomalies would be solved if you realised that we are talking about alternative forms of cash. Obviously, it requires us to consider a different use for the term cash. Although I am not entirely sure that there is a standard. I believe the reason people are adopting digital alternatives is that they see them as cash, and some of them, in fact, are cash.

M-Pesa just appears, to me, and I may have got it wrong, to be a system which increases the velocity of the circulation of cash, and that is in a country which had, possibly, a lot of surplus labour willing to work, which has probably caused the growth. So, I think a lot of the anomalies you see are because there are different reasons. There is no one thing for digital cash, which I think you highlighted in one of the sections. I believe it might have been a reasonable start to have specified a monetary system. We are only talking about cash here, and I believe we need to start and say what cash is. I think it is a way of transacting immediately, or near instantaneously, and as we have seen, all modern technologies are, perhaps even faster than cash, and perhaps more efficient, but it is still, I believe, worth the term cash. I believe also, that as long as there is an equivalence and equality between each alternative value, there is no reason why there should not be multiple variations of cash type existing in the same system, at the time.

I believe that cash keeps the system safe, and there may be a reason for which even a cost of 3% might well be necessary to keep the system safe. In the paper, you do pick up an awful lot of points, but do not seem to bring them together. One of the things that comes out a lot is trust, which is the most important thing, but I also believe that people probably will trust more if they believe and they own the system. We have to consider a whole system. It seems to me there are at least two other conceptual entities we have to define, and I am going to use the terms currency and money. I would define money as a set of objects which can be relatively easily turned into cash with a reasonable expectation of value. I believe then currency is the mechanism by which a society manages money. It is only at this level that trust can truly be established. Unfortunately, I am not sure that there is much trust at the moment. Regrettably, I do not think that the arguments made by politicians and regulators, that, “Nobody else saw it coming, so I am not to blame,” goes down too well.

Trust would be further eroded if new tools, like negative interest rates, are asked for, rather than regulators and governments managing risk in the first place, and perhaps, ask yourselves what will happen if the new type, or types, of cash go wrong, and politicians and regulators again say, “It looked like a good idea at the time.”

I am quite sure there are enough good ideas in this paper to enable the essential characteristics of these objects to be created.

My motivation for speaking is my belief that Bitcoin is a serious threat to society and the monetary system. That is not to say blockchain might not be useful, but only as a ledger system, though there are now suggestions of high costs in terms of resources to implement it. The inherent flaw in Bitcoin is the finite limit on the number of coins in issue. This makes it totally unacceptable as a currency, where to match the production of the economy you have to change the amount of money, which is highlighted in the paper.

While I genuinely agree that the authors have tried to be impartial, I do have some serious concerns about the linkage of a cashless society to issues like immigration, without first asking if there is an alternative or more appropriate solution. I do note a general concentration on the primacy of money, especially when considering a store of value. In the paper of course, negative interest rate policies appear to invalidate that, and I think the confidence of the financial system will suffer. Though at one stage there was an attempt to introduce a concept of wealth being somewhat different to money, ultimately I do not perceive any store of wealth in money, or other financial instances, is permanent. There is no worthwhile value without work, or the ability to control the work of others. Whatever we do to money, currency, or cash, the only important question is what does it do to the amount of work done?

The Chairman: Thank you.

Mr Collier: I think that there is a small confusion about the definition that cash and money, and that is why we have taken the simplest possible definition of cash as being notes and coins. It is not to replace money, and I think you picked up about cash being the best form of stability within an economy. I am not sure I am totally in agreement with you, for the sheer difficulty of transportation and handling cash, and the desire by people in the economy. It is quite clear when you go to pay for your coffee, most people are paying contactless, or cards, without having the cash in their pocket and transferring. People are moving towards it, and whether it is the most stable, or not the most stable, I think it is inevitable that we are, around the world, moving to a de-cashing situation.

In some economies, this is a huge advantage. So, we make a case study of M-Pesa in Kenya, and you may have picked up that M stands for money, or mobile. Pesa is Swahili for money, and just the sheer fact that where there is no Internet, there is not very much in the way of banking system, and people having to transport very large sums of money from urban areas to rural places, which is difficult, expensive and hazardous. Not using cash, but using mobile forms of payment, has just totally revolutionised the economy there. I am not suggesting it has revolutionised the economy here in the UK or in the Western World, and that is why the answer and the desire are different in different economies at different state of development, and also, as I said, for different stakeholder groups.

We find it very interesting that in countries like Sweden, you almost find it difficult at the moment to go in and spend your Krona in shops. People do not take it, and their attitude is almost, “Well, why would I?”

Germany is way behind some of the other countries in the Western world, and you have to ask yourself, why might that be, and I do not know the answer. The only thing that worries me, and I picked up on one of the risks that we have on a totalitarian government, that you might be worried that, all of a sudden, the government knows absolutely every movement that you make, if you have everything done by electronic transfer. It is possible, and I am not saying it is the case, that a lot of Germans have, in the past, either lived under, or remember, a rather totalitarian society. Or those that have lived in the GDR, understand and know it as well, and might themselves be rejecting the use of electronic payments in lieu of cash, for that reason.

Mr Houlston: Could I just try and explain what I understand by M-Pesa? It appears to me that it is a system that transfers credits on phones and I assume that those credits have to be paid for in cash. There does not appear to be another version of cash in the system, and as such, the entry and exit points are cash, and M-Pesa is not a currency system, it is a method of transmission. Yes, that method of transmission reduces costs but it is still reliant on cash. There are other forms, like digital, that tend not to do it that way, but unless you understand the differences between the systems, I think you will not explain your anomalies.

Mr Collier: Yes, you are quite right, M-Pesa is not a new currency, and we are not talking about new currencies, but it is replacing the use of cash in the transference of the money, from physical money to electronic money.

Mr J. G. Spain, F.I.A.: We are not in a totalitarian state, but certain people do have their banking facilities circumscribed. And it can sometimes happen in quite a violent way: “You are no longer wanted as our client, go away. You have a problem? Sorry about that, we cannot tell you why.” Finally, Apple Pay, Google Pay, are these not new totalitarian outfits?

Mr Achord: It is very interesting, with all the developments in different payment intermediaries. This brings back one of the points that Mr Houlston made in the cost of cash, whereas the cost of physical cash is quite massive. Those costs are in transport, storage and updating machines and such. So, those costs probably go back into the economy, but if you have Apple Pay, Google Pay, or if you are in a small country and the payment processor is a company from another country and 2% of every payment goes to the payment processor after ten years you are going to have 98% to the tenth power of the amount of money that you had before. So, that could be where we are going.

A Speaker: I thought that the paper was very helpful and provided lots of food for thought. You pick up on society and I think the impact on society is really important. Financial exclusion, Big Brother watching, but what about the disconnect people have with money?

So, let me give you an example. When I was young, I used to go out with £50 and once it was spent, it was spent. Today, people just spend and spend, and it is the same thing with gambling and Internet shopping. What level of research have you done in that area?

Mr Collier: There is a very interesting exercise going on in certain boroughs in certain states in Australia where the benefit is not handed out by cash but by a reloadable debit card. The idea is that someone on benefits, for example, cannot spend the cash, because of the bar codes or QR codes on alcohol, on gaming, and then presumably, on drugs as well. Although there are ways round it, and there is a big debate going on in Australia about whether or not this is working, I think there is sufficient evidence to believe that the federal government there is looking to roll that out.

In Jordan, which is not mentioned in our paper, and we do not associate Jordan necessarily as being particularly high-tech, Syrian refugees who are being looked after by different United Nations agencies are having their benefits paid, not in cash at all, but using a blockchain facility at stores, and there is no doubt about it that at least electronic payments of sorts do give you a way of controlling certain aspects of expenditure.

Mr S. McCarthy: I must confess I have not read the paper, but with regard to the impact on something like quantitative easing (QE), if you did have a cashless society, would it move away from central banks by bonds, and things like that, because that is not very effective if you are trying to boost consumption as we have seen. It just creates asset price inflation. Have you looked at ways that that could be done more effectively?

Mr Achord: I think it is something worth looking at and QE is very complex. You can read all about it, and there are lots of different facts or data and lots of different interpretations. Whether it was good or not, I do not know. The banking system is still intact, for better or worse. I think if QE had not happened, the world would be quite different, and financial services might be quite different.

Mr Collier: You talk about QE but the opposite can also be true. My guess is there will be a central bank digital currency in due course, and that may not be too far away. We were talking about the £20 note in your pocket being a loan, by the Bank, or a loan to the Bank of England, “I promise to pay the bearer,” or the £20 that you have deposited at HSBC is a loan to a trusted borrower, HSBC. Ask yourself, if you own Bitcoin, to whom have you lent your money? The answer is you have not a clue to whom you have lent your money, but if the Bank of England introduced a cryptocurrency, a blockchain type currency, a digital currency, you know exactly to whom you have lent your money. And because the Bank of England now has all the accounts, what it does in sub-accounts to allocate to different clearing banks or not, I have no idea. That is something which we will look at in phase 2; the Bank of England could just drop money into your accounts.

So, QE would look very different, but the opposite would be true in NIRP, that if it wanted to take money out of your account, in terms of negative interest rate, it just sucks it out as well. That could all happen in a cashless society. It would still be Sterling, it is just a different way of handling it, if it were the UK, or it could be from any other country. The Bank of England have looked at a proof of concept but we do not know exactly what their answer is and what their reaction is. My guess is they will not want to be the first, necessarily, to put their toes in the water, but there are going to be digital currencies by central banks somewhere around the world in the not-too-distant future.

Mr Achord: You might be talking about helicopter money, effectively.

Mr McCarthy: This would allow something different to helicopter money. A much cleaner way to do it.

Mr Achord: To implement helicopter money, and I guess the question will be will helicopter money stimulate the economy or will it just feed inflation? You probably have to couple helicopter money with other kinds of economic policies to ensure that it spurred growth and did not just add money to a fixed set of goods.

Mr A. M. Barringer, F.I.A.: I have great admiration for the work that has been in done in collating such a tremendous amount of information. Obviously, a lot of work has gone in, and I do note that there is going to be a phase 2. But the tremendous volume of information, although it is collated, does not seem to lead to even tentative conclusions at the moment. So, I look forward to phase 2 when that will be developed more.

I first visited Kenya about ten years ago and I was amazed to come across this system, which we now have discussed, called M-Pesa, where people could pay each other using their mobile phones. I had never seen anything like this before, and my reaction was, “Why have we not got this in the UK?” I asked some more questions and I found that people did not even need a bank account. All they had to do was go to an agent to get the money put on their phone. They could send it up country, as you were saying, to perhaps their relatives in other provinces, and this replaced, as you indicated, a system which was very much more risky in the past, where you just had to give the cash to a trusted agent.

What surprised me was that not only was it a very advanced system which we do not seem to have in the UK even now, because you did not need a bank account, and, as far as I am aware, one needs a bank account to link up to all the non-cash transmissions. It seems that the regulatory system in Kenya allowed the telecoms company, SafariCom, to effectively allow these transmissions without having a link with the banking system. Now, this is obviously a regulatory issue, and I wonder is the regulatory issue preventing other transmission mechanisms developing in this country and other advanced payment economies, because they have to be linked to a bank account, as a means of control?

Mr Collier: The M-Pesa system, and what is so beautiful about it, exists because most areas in Kenya do not have Wi-Fi or Internet access. So, the people are using M-Pesa on the sort of mobile telephones that we think are Jurassic, and are probably rolled out for about $10 a piece, and this is something which is akin to the security device that your bank gives you for free so that you can do some Internet banking, and here, it is a different situation. I do not know if there is a regulatory reason why we cannot exchange money on our mobile telephones. I think we do to an extent already, when you see a charity type advert and text save to a certain number, and £5 gets debited from your mobile telephone account and £5 gets credited to theirs. So, I think it does happen to an extent.

I do believe SafariCom M-Pesa is regulated. The money is not a loan to SafariCom, unlike a loan to HSBC or Barclays, it is money held by SafariCom, and then their money is then held by a third party, and if SafariCom were to go bust, the money is not affected. So, I think that is true.

Ms Rochemont: M-Pesa is available in Kenya and about 20 other African countries now. It is also available in some parts of Eastern Europe and it is being increasingly used to address the issue of access to Wi-Fi infrastructure in rural areas of India. So, it is one of the most fascinating trends that we are seeing at the moment from Africa and Asia-Pacific. It is a crossover of innovation. So, we see Asia and China, in particular, exporting some of the innovations into Africa, especially for closed border payments with some particular products, and we also see some African innovations reaching out into Asia. What we did not expect to see over the past few months is some of these innovations starting to edge into Eastern Europe and reaching out for us. One of the ways this is happening is through our keenness to serve Chinese tourists. For instance, when you go to Heathrow Airport now, one of the lounges take payments via WeChat. So, next you might be using WeChat for your payments, this is an innovation coming right from China. So, are we sitting back?

Mr T. J. Birse, F.I.A.: If you donate £5 to a charity on your mobile phone the charity gets £5, if it is a big charity which is advertising on television. If it is a local charity and you set up these arrangements, £5 donated by phone gets the charity about £4.05, and the rest of the money the telecoms companies suck up, and they do not necessarily make that abundantly clear. The biggest single sector that continues to use cheques is the charity sector. The charity commission gives a very clear steer that payments out from charities need to be authorised twice, so a cheque is the obvious mechanism. The CAF (Charity Aid Foundation) Bank have a very good dual authorising system for electronic banking. The other clearers are just beginning to catch up, but payments made over the counter to a retailer seem to be a non-starter in anybody’s system. If one regulator is saying two signatures are needed, and another regulator is pushing for electronic banking, I think the Bank of England has to get its act together.

The Chairman: Yes. So, we just have one comment from Parit.

Mr Jakhria: There is quite a lot of discussion on M-Pesa, and I just want to say, I have the good fortune to have been born and brought up in Kenya, and I think some of the questions asked, effectively, why did it become so prevalent? Why was there a spark in Kenya? I think it is worth just touching a little bit on the geography of Kenya. Kenya is relatively large in terms of land mass. It is about 800 km across and 800 km long and there is a lot of very, very difficult terrain. So, if you think of the evolution of banking, when I left Kenya to come here about 20 years ago, there was an intention to roll out bank branches across the country, but even that was difficult. So, not even every village had its own local bank branch. So, if you think of that as first-generation banking, the next generation, which it never quite saw, was telephone banking, where you have telephone lines connecting the entire country. So, it managed to jump three generations, because it went straight to mobile banking.

All you needed was a mobile phone and 2G Internet, and the biggest reason it succeeded was that it helped businesses. There is a lot of migration in terms of working, linking it from rural to city areas, so it allowed repatriation back to the rural areas, and that I think was the single biggest reason it expanded in use. In terms of the licensing, yes, you are absolutely right that it is denominated in Kenyan Shillings, so it is the same currency. The telecoms got in quite quickly and they managed to have a deal with the regulator, and it is very interesting. So, now, the banks in Kenya are applying for a telecoms licence because they feel they are behind the curve, and they are being disrupted by telecoms. So, it is a case of a disruptive technology.

Mr R. A. Galbraith, F.I.A.: I am wondering if this is starting to change the definition of money. I am not saying cash, because at the moment, as long as we have a cashless society, we are talking about going in, waving our contactless, using our Apple Pay, Google Pay, whatever it might be, but there is the next level of transactionless payments. I am wondering if that will be the point at which things start to change, because as soon as you move into the blockchain, as we said, potentially you could remove the old-fashioned banking sector. People go out on their night out, you do not need to carry cash, you do not need a card, you have potentially facial recognition or something else, you do not even need to think about it anymore, and I am just wondering if that changes the definition again and we are almost out of date already.

Mr Collier: The point I should have made about our friends in Jordan is that the payments are made by eye-recognition. And this is in Jordan, which is hardly Silicon Valley, and so, yes, maybe that is going to happen. We have thumbprints to an extent on Apple Pay, do we not? Eye-recognition, why not? It is just a form of transferring assets from someone to somebody else, but not using paper or physical money.

Miss L. I. Lobo, F.I.A.: Thank you for the paper, it is very thorough. In terms of structure, do you think, given where we are at with the wider debate on cryptocurrency and different forms of money, it might be better to structure it as one part being about blockchain and distributed ledger frameworks that exist, or are available, and then, an alternative structure for the store of value, which seems to be the other part of the equation. The paper does touch on issues like immigration, political banking, all elements of the economy, all elements of our lives and it feels that going back to the axioms of what is good money helps us to organise our thinking.

Mr Collier: When we started on this paper, I think we were looking mainly at the benefits of taking cash, notes and coin, out of society, and then we discovered that it was just so much more, hence phase 2. I think that you found, for those of you that have read the paper, yes, it is quite lengthy at over 40,000 words, but, on-balance, it is an easy read, and I do recommend it to you. We have written a little bit about a lot of different subjects, and we discovered that some of those subjects needed a vast amount more rigour, and blockchain technology is one of them. Certainly, we have already hinted at a change in capital markets, for example, changing the eco-banking system. These are not necessarily involved in a cashless society, we have veered off at a tangent, but there is no doubt about it that if cash were withdrawn from society, there will be some people who demand the use of cash, for whatever reason, and it might be not for the right reasons, but it might be for perfectly genuine reasons. They will look for different forms of payment, and a digital currency, whatever it is.

I am not suggesting Bitcoin, as I have said, since you do not know to whom you are lending your money with Bitcoin. If the European Central Bank or the Federal Reserve issued a central bank digital currency, why do we not all use it? What is the Bank of England going to do in terms of financial stability here in the UK? These are very big issues that are not specifically connected to taking cash totally out of society, but are certainly associated with it, which is why we do need to look at these things in far more rigour in phase 2.

Mr M. L. Pearlman, F.I.A.: First, thank you to the paper’s authors for such an incredible collection and summary of a vast amount of information: it has been really useful. There is a lot of talk about decashing and the inevitability of reducing the amount of cash in society. On the other hand, you have certain items that happen, or can happen, in a cashless society: negative interest rates; totalitarianism, and so on, which are a big worry. I was just wondering if there is a gap between decashing and cashless and can some of these things only work if there is zero cash in society? Is there some kind of tipping point at which you can move from one phase to the other?

Mr Collier: We witness decashing going on in front of our noses. However, the interesting thing is, the amount of notes in circulation in the UK is growing, and it is growing at a rate of knots, and we are not really sure we understand why. There are a number of reasons why the notes and coin might be increasing and, certainly, the Bank of England is in between a rock and a hard-place. It may not feel necessarily that it is all for the right sort of reasons, but to restrict the amount of cash in society, if you went to your ATM and cash was not coming out, because the Bank of England want to restrict it, that would take away a confidence in the currency immediately. So, they really are between a rock and hard-place on that particular issue.

We are already seeing a situation where banks are closing branches all the time, because there are cheaper ways of conducting their business. There could come a time when the economies of scale no longer mitigate the cost of handing cash sufficiently, and they withdraw ATM machines, especially in rural places. What happens to the financially excluded at that stage? How do we protect them? These are the issues. My problem is not: “Is there a tipping point? Will it happen?” Different people on the working party have different ideas about whether it is going to happen and whether it is not going to happen, or whether it is going to happen in my life time, which is less likely, than in your life time, which is more likely.

I think it is going to happen. It is going to happen in different places around the world at different paces. In Sweden they are almost there. I think the thing that we have to look at, and which perhaps they did not do sufficiently in India, is to get the transition right, so that if it happens, by design or by stealth, then certain people in our community are protected.

The Chairman: I have two remarks in closing, the first being in relation to some of the comments which Sam (Achord) made about NIRP. Having been a former central banker many years ago, I saw a little inside the lion’s den, on how monetary policy is implemented. I think, although it would be a difficult thing to prove, that in a purely cashless society, the implementation of monetary policy should be more effective, particularly where you are trying to encourage spending.

Central bankers will argue that it is very easy to tighten monetary conditions, but on the other hand, when you loosen things, sometimes there becomes a point where things become so loose that people do not want to spend anyway, and banks do not want to lend. We end up pushing on a string.

So, if you did have a purely cashless society, there would be no ability for people to hoard cash. If you are earning a negative interest rate on your bank account that might encourage spending.

The final remark I would make is in relation to the cryptocurrencies, which have been receiving a lot of attention recently. If you look at the global market capitalisation it is about $500 billion, it was a couple of billion this time 12 months ago.

Cryptocurrencies prove that you can use the Internet network to safely and securely transmit information, so you have various different types of cryptocurrencies. But I think what that large increase in value asks is, perhaps, why have we not been thinking about this before?

Obviously, now that everyone has a hand-held device, and everyone is essentially plugged into the Internet 24/7, the idea behind a network over which you can safely and securely send transactions really opens up. So, I think there will be some kind of movement in this area and so these are very exciting times.