1. Introduction

In the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) member countries, insurance expenditure, measured by taking direct gross premiums as a percentage of Gross Domestic Product (GDP), was 8.9% in 2018 (OECD, 2020); this value demonstrates the importance of the insurance sector in the world economy. One of the professions highlighted in insurance organisations is that of the actuary, who may have various responsibilities such as product pricing, calculation of liabilities, risk management, investments, and capital adequacy (Toronto Centre, 2015). For several years, the actuarial profession has consistently been regarded as one of the most highly skilled, attractive and reputable jobs in society (Society of Actuaries, 2016).

Specifically, actuaries are professionals “(…) who use their mathematical skills to help measure the probability and risk of future events. They use these skills to predict the financial impact of these events on a business and their clients” (Institute and Faculty of Actuaries, 2014). Actuaries are experts in risk measurement and management and have specialist knowledge in different areas, including mathematics, statistics, finance, and business, that enables them to perform comprehensive analyses to quantify the financial impact of risks. Thus, actuaries have become solvers of complex problems and strategic thinkers, trained in the assessment of the financial implications of future contingent events and providing high value information for the creation of new business opportunities (International Actuarial Association, 2013).

The exponential development of global financial systems and the availability of massive data in recent decades have increased the relevance of the actuarial profession in loss reduction, uncertainty management, and business performance optimisation (Institute and Faculty of Actuaries, 2017). With increasing uncertainty and explicit risks, the management of the decision-making process is fundamental for sound business, and ideally, it should be an analytical, rigorous, and pragmatic process. This requires top-level executives to be qualified to recognise the particularities of the different courses of action that can be followed (Armstrong, Reference Armstrong2006; Kahneman, Reference Kahneman2011).

Decisions made at a senior level have a significant impact on a corporation, and the corporation therefore requires appropriate methods that can assess and mitigate the multiple risks, based on timely, quantified and synthesized information (David, Reference David2011). Although there is extensive literature on risk management in decision-making (Lu et al., Reference Lu, Jain, Zhang, Lu, Jain and Zhang2012), the actuarial approach seems to be treated differently because of its particular contribution.

This paper addresses, in a systematic way, the importance and contributions of actuaries in business management roles for the performance of organisations; while it mainly draws on experience from the insurance industry, it may also apply to closely related areas such as pensions and banking. After the introduction, the business context is described in section 2. The theoretical and methodological frameworks are then presented in sections 3 and 4 respectively. In section 5, the results of the research are synthesized. Section 6 discusses the importance of actuarial management in data science. The paper ends with conclusions in section 7.

2. Business Context

Multiple empirical analyses have formally shown that countries of any income level that deepen their insurance sectors succeed in promoting better long-term economic growth and development, in a faster and less volatile way (Outreville, Reference Outreville1990; Han et al., Reference Han, Li, Moshirian and Tian2010; Pradhan et al., Reference Pradhan, Arvin and Norman2015; Liu et al., Reference Liu, Lee and Lee2016; Ul Din et al., Reference Ul Din, Abu-Bakar and Regupathi2017). Insurance is regarded as a key element in today’s globalised economic systems; income, life and equity protection are among its benefits, and it has a positive effect on savings, gross capital formation, total productivity, public expenditure, foreign direct investment, trade opening and financial development (Apergis & Poufinas, Reference Apergis and Poufinas2020).

The insurance industry contributes to the banking and stock markets, by providing greater stability, security and guarantees of their capital, and has a positive macroeconomic impact as long as there is prudent growth in real production (Hassan et al., Reference Hassan, Sanchez and Yu2011; Ductor & Grechyna, Reference Ductor and Grechyna2015; Durusu-Ciftci et al., Reference Durusu-Ciftci, Ispir and Yetkiner2017; Hou & Cheng, Reference Hou and Cheng2017; Yang, Reference Yang2019). However, it is also true that the volatility of domestic and international business markets, the uncertainty of macroeconomic variables, changes in the behaviour of both the population and the environment, and public policy regulations, among other things, generate constant uncertainty in the insurance sector. All this must be addressed, mainly with the support provided by the actuarial management of insurance institutions (Outreville, Reference Outreville1998; Apergis & Poufinas, Reference Apergis and Poufinas2020; Balcilar et al., Reference Balcilar, Gupta, Lee and Olasehinde-Williams2020).

In addition to insurance and banking, the technical expertise of actuaries provides key elements for managers in the public sector, such as in regulatory, supervisory, and control bodies, and across private sector organisations in risk management, finance, analytics, IT and related positions (Haberman & Sibbett, Reference Haberman and Sibbett1995). The role of actuaries varies by country, area of practice, corporate structure, business culture and the maturity of the financial system, among other things. Even so, in all cases an actuary in a senior leadership role has the responsibility to maintain a technical, yet political, position in a world with considerable uncertainty. Sound management skills such as teamwork, effective communication and negotiation – within highly technical teams and also among non-technical staff – and an innovative way to search for new business opportunities are now required (Rudolph, Reference Rudolph2017).

Not only best-in-class technical skills but also high standards of conduct and practice and the rigorous qualification process of the actuarial profession have given actuaries an excellent profile for managerial positionsFootnote 1 (Haberman & Sibbett, Reference Haberman and Sibbett1995). Standards of practice, for example, provide a framework of guidance to the actuarial community on relevant issues that reflect appropriate actuarial practices in different areas when performing a professional assignment; these standards range from the acceptance of an assignment and data quality to documentation and monitoring, including assumptions and methodologies, model governance, process management, peer reviews, and communication, among other things.

Since the development of managerial skills to allow roles to be taken at the C-Suite level is increasingly important, the research question to be answered refers to the main contributions of actuarial management in insurance decision-making in the twenty-first century.

3. Theoretical Framework

Management decision-making is considered a constant challenge in managerial sciences. From a holistic viewpoint, an entity has internal structures that interrelate on a daily basis and generate a complex system of relationships (Forrest et al., Reference Forrest, Nicholls, Schimmel and Liu2020). A company can therefore be understood as an organisation with a deep-rooted culture, implicit philosophical values and daily operational routines, among other things, in which managers build their decisions with the available facts to choose a course of action; the managers must observe, research, collect and filter information, analyse possible scenarios, have clarity about what needs to be achieved, understand the environment and corporate structure, and finally know how to evaluate, quantify and assume risks to choose the best possible alternative (Simon, Reference Simon1997; David, Reference David2011; Ansoff et al., Reference Ansoff, Kipley, Lewis, Helm-Stevens and Ansoff2019).

The literature on the management decision-making process can be summarised in an aggregated way as following three types of conceptual model: (i) descriptive models, which study the behaviour of decision makers once they have taken an action and review the factors that most strongly influenced the process; (ii) prescriptive models, which are oriented to what managers should or can do to make decisions, inferring the mechanisms that enable people to make good decisions; and (iii) regulatory models in which the actions that individuals should take are investigated from a theoretical approach, with consistently logical management instructions being provided for reaching the best choice (Huber, Reference Huber1980; Moody, Reference Moody1983; Michail & Boughton, Reference Michail and Boughton1997; Meacham, Reference Meacham2004; McKenzie et al., Reference McKenzie, van Winkelen and Grewal2011; Rodríguez-Cruz & Pinto, Reference Rodríguez-Cruz and Pinto2018).

In all the approaches, the use and management of information in the management decision-making process is predominant; structured information must be recognised as a strategic resource, which allows changes to be captured in the current era of digital transformation and is essential for innovation from the construction of new knowledge (Citroen, Reference Citroen2011; Kahneman, Reference Kahneman2011). Information, which is generally neither complete nor sufficient for achieving solutions, is an element with high added value as companies manage to extract the maximum benefit for their different business units, understanding the tactical and operational complexity of the internal and external environments affecting the corporate structure (Simon, Reference Simon1997; McKenzie et al., Reference McKenzie, van Winkelen and Grewal2011).

By looking at the advantages of information management as a strategic element for an organisation, the actuarial approach has gained a leading role in the business decision-making process of insurance companies. However, the analysis of actuarial management in the business environment was not a topic that was thoroughly studied in the nineteenth century and the first half of the twentieth century; the initial in-depth reviews can be traced back to the second half of the twentieth century,Footnote 2 particularly in the discussions that took place at the annual meetings of the Society of Actuaries, specifically its Committee on Management and Personal Development.

Essentially, these analyses highlighted the classic topics from the viewpoint of contributions to risk management, assessment and mitigation, such as: (i) risk identification and the development of business plans consistent with the appetite of senior management; (ii) the optimisation of profitability decisions by strengthening managers’ ability to carry out constant monitoring and review in a reliable and timely manner; (iii) strengthening business growth plans so that they were adequately supported and remained possible, even under a range of adverse business conditions; and (iv) technical advice to executives to improve the control and coordination of risk-taking in different parts of the company (Jay et al., Reference Jay, Burrows, Bourdeau, Clark and Rugland1977; Goford, Reference Goford1985; Hickman & Heacox, Reference Hickman and Heacox1999).

Authors such as Richardson (Reference Richardson1949), Clennon et al. (Reference Clennon, Kraegel, Lyle, Maurer, Paige and Robertson1975), Corbett et al. (Reference Corbett, Murphy, Smith and Reichman1989), Rudolph et al. (Reference Rudolph, O’Connor, Oh and Lemay1999) and Michail and Boughton (Reference Michail and Boughton1997) regard as fundamental the transfer of knowledge by the actuarial team leader, who must always advocate the development of a culture of managing corporate risk at all levels of senior management; they also describe positive experiences in areas other than the classic actuarial areas (pricing, reserving, product development, assets/liabilities management, investment banking, etc.), such as supporting the solution of sales problems related to market research, controls and metrics to evaluate sales force quality and agency management, business quality measurement, cost distribution analysis, marketing methods, and the compensation of agents, supervisors and managers. In addition, these works draw attention to the importance in any organisation of company managers adopting risk management as part of their daily thinking.

4. Methodological Framework

A systematic review of the literature was carried out in order to consolidate and summarise the existing information published over the past two decades regarding the contributions of actuarial management in business organisations. A rigorous methodology was used to identify, select, analyse, synthesize, and interpret all evidence related to a structured research question, in a scientific, unbiased and replicable process (Tranfield et al., Reference Tranfield, Denyer and Smart2003). The research question, search approach, screening process, selection of papers, and data extraction are described below.

4.1. Research Question and Selection Process

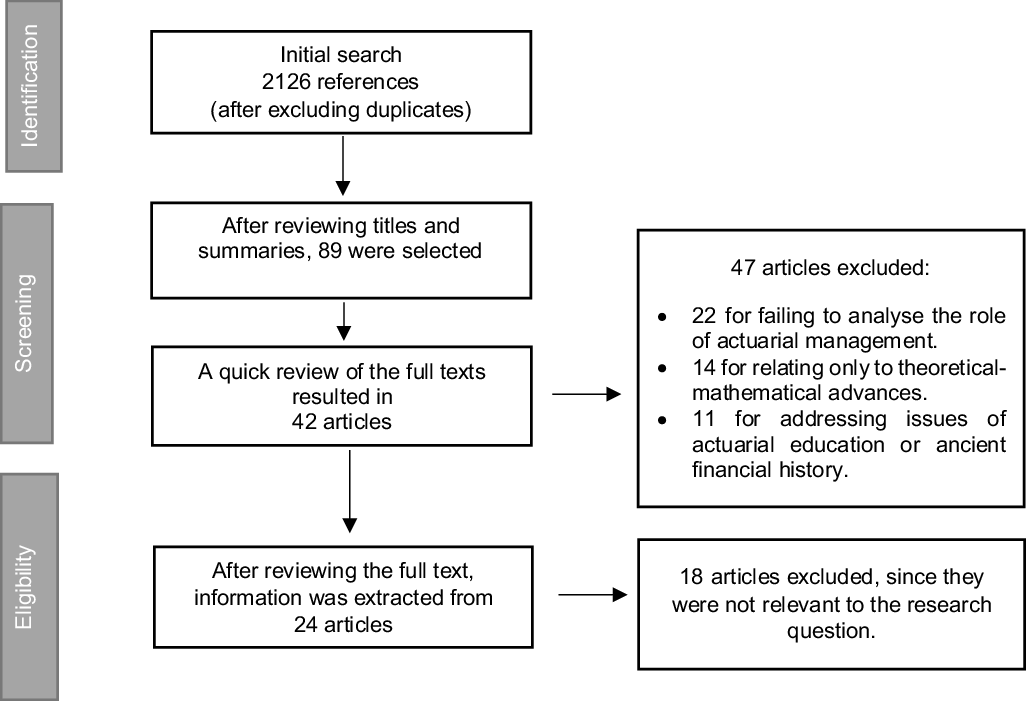

The research question is what are the main contributions of actuarial management in business decision-making in the twenty-first century? This was defined in a SPICEFootnote 3 framework (Booth, Reference Booth, Booth and Brice2004), which is considered an adequate approach for the formulation of inquiries in a qualitative context. Figure 1 sets out the process map for answering the research question, from the selection of electronic databases to the identification processes and the final choice of primary studies.

Figure 1. Map of the systematic review process carried out.

Source: own elaboration.

4.2. Search Criteria

The review covered information published on the Web, including scientific articles, working papers, and book chapters, among other works, released in and after the year 2000. The search criteria used for titles, summaries, and keywords were (managerial ADJ decision ADJ making OR policy ADJ maker OR enterpr* OR compan* OR insurance* OR business* OR industr* OR firm*) AND (actuary OR actuarial ADJ science) AND (strateg* OR role* OR responsibilit* OR governan* OR impact*). The electronic databases used were the following: Jstor, Econlit, Science Direct, Scopus, Springer Journals, Taylor & Francis, Emerald and Web of Science. Additional searches were performed on Google Scholar, Econpapers, Doaj, Scielo, Redalyc, soa.org, casact.org, actuaries.org.uk and actuaries.org. After removing duplicates, a total of 2,126 documents remained.

4.3. Screening and Selection

The inclusion criteria for the first stage of screening were focused on writings that address the issue of actuarial management and study its role, impact and/or scope, while the exclusion criteria were that the document did not analyse the implications of actuarial management in business decision-making or did not explicitly refer to the responsibilities and/or the role of the actuary.

An initial review of the 2,126 articles was carried out by title and summary, selecting those relevant with respect to the originally defined question; 89 documents were obtained for a full-text quick review. In the next step, 47 publications were excluded since they did not analyse the specific role of actuarial management (only including a theoretical-mathematical approach, educational training for actuaries or ancient financial history).

To ensure that the writings were of adequate quality and relevance, the remaining 42 documents were evaluated using the following criteria: (i) pre-eminence of content that provided a response to the research question; (ii) appropriate description of the environment regarding the analysis being done; and (iii) rigour in the methodology used for the investigation. Finally, after the full-text review, 24 articles were kept for data synthesis and were considered as the primary sources of data for the systematic review.

4.4. Data Extraction

After considering the number of articles and the variety of contributions, the documents were grouped into the following three broad categories in order to perform a compact data synthesis:

-

(i) Actuarial control cycle and management of uncertainty;

-

(ii) Quantitative strategic risk framework and financial modelling; and

-

(iii) Enterprise risk management with a value-based approach.

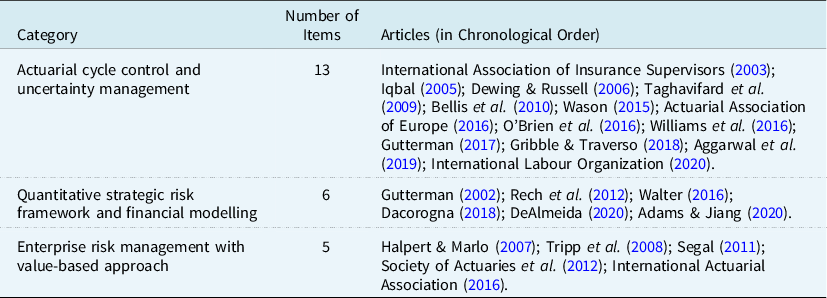

Finally, relevant information specifically addressing the contributions of actuarial management in business decision-making was screened and extracted from each document. Table 1 contains the selected articles in each category.

Table 1. Classification by Categories

5. Results

This section consolidates and summarises the results from the analysis into the three broad categories mentioned in section 4.4.

5.1. Actuarial Control Cycle and Uncertainty Management

When analysing the financial consequences of the different risks in an insurance entity (or government institution), the actuarial team becomes fundamental for business knowledge and decision-making. A very useful conceptual framework for the ongoing management of a financial enterprise is the so-called actuarial control cycle,Footnote 4 which was studied by Bellis et al. (Reference Bellis, Lyon, Klugman and Shepherd2010). The control cycle can be thought of as a systematic approach to problem-solving that divides the thought process into the following three steps: (i) define the problem (understand the background, make a full identification of all the problems and obtain a clear specification); (ii) design the solution (develop and implement the solution from modelling); and (iii) monitor the results (respond to experience and feedback mechanisms).

The actuarial control cycle process can be carried out in an environment that shapes the decisions made, highlighting the quality required by institutional communication; actuarial teams can develop technically outstanding models and analyses, which may or may not lead to correct decisions, sound strategies, and effective plans, depending on whether or not the actuarial managers understand the needs of senior management and are able to deliver appropriate messages (Bellis et al., Reference Bellis, Lyon, Klugman and Shepherd2010).

A key advantage of the actuarial profession is its ethics and the reputation of actuaries in most countries of the world. Increasingly, actuarial associations provide support and have in place, among other things, strict disciplinary processes, continued robust professional training (in both quantitative and management skills), and high standards, which remain predominant; what is key is the “how” in conduct, rather than the technical “what” of the results (Gribble & Traverso, Reference Gribble and Traverso2018).

The risks and opportunities faced by a company must be examined and understood in a comprehensive way, by studying the economic situation and its future environment, the behaviour of consumers, the competition, and many other factors. Senior executives or chairmen find, in the lead actuary, someone with an adequate understanding of the critical need of the existing operation to find new value-added market niches (Iqbal, Reference Iqbal2005). This allows senior management to gain a better recognition of the company’s risk profile and to make a better allocation of capital and provides the opportunity to evaluate the consequences of different business plans drawn up under a variety of possible future conditions (Taghavifard et al., Reference Taghavifard, Khalili-Damghani and Tavakkoli-Moghaddam2009).

In addition, the literature on the financial services industry points out the importance of having the lead actuary advising the board of directors of the entity. In the insurance market, customers and shareholders perceive the actuary as technically trusted, credible, and analytically oriented, as well as a guarantee of good financial counsel, because of the vision an actuary can offer when pricing complex products (O’Brien et al., Reference O’Brien, Gallagher, Green, Hughes, Liang, Robinson, Simmons and Tay2016). Because of the complexity and long-term nature of the insurance industry, corporate governance requires the lead actuary to have a positive influence on the decisions of senior management. As an advisor to the board of directors, the actuary is given confidence in the audit process and in identifying material risks for the solvency of the insurance company (Dewing & Russell, Reference Dewing and Russell2006); as a supervisor, in an act of prudential financial management, the actuary assumes the duty to report to the regulatory authorities irregularities affecting the interests of policyholders (International Association of Insurance Supervisors, 2003).

With the implementation of Solvency II, new roles are required in areas where actuarial management is fundamental to an insurance entity (Actuarial Association of Europe, 2016). Among the main responsibilities of actuaries, as key supporters of the actuarial function, are the valuation of the company’s assets and liabilities, the calculation of the value at risk of loss, the monitoring of risks within the commercial strategy and the successful implementation of a robust risk management system; this oversight is expected to make material contributions in a precise, clear and understandable way, and the recommendations will be of interest to senior management (Wason, Reference Wason2015).

Similarly, from a regulatory point of view, the importance of actuarial assessments and expertise for decision-making in public policy and government reform processes is also illustrated, recording the strengths of actuaries in establishing reasonable and appropriate premises, as well as in comprehensive evidence-based analysis (i.e. coverage and benefit-sharing, equity assessment in a system, design and fiscal impact of a reform). Under conditions of uncertainty, the actuarial approach allows reliable advice to be given to decision makers about schemes related to pensions, health, social investment, social insurance, and other aspects of interest to policymakers (International Labour Organization, 2020).

The management of uncertainty is essential in financial institutions. Gutterman (Reference Gutterman2017) sets out the benefits of having an actuarial vision in the business decision-making process, and the importance of creating effective and adaptable plans that recognise and address the differences between risk and uncertainty; while risk can be defined as the effect of variation resulting from the random nature of the results, uncertainty involves the degree of confidence in understanding the impact of hazards that are not easily measured. This understanding, granted from an actuarial management perspective, allows models to have a set of assumptions that are more consistent with the historical information available, characterising a reasonable representation of the futureFootnote 5 and identifying the actions necessary to reduce the adverse consequences of uncertainty (Gutterman, Reference Gutterman2017). Such a conceptualisation should lead senior management towards more effective management in the firm’s corporate culture.

Regarding the understanding and management of uncertainty, the work of Aggarwal et al. (Reference Aggarwal, Bird, Cox, Durkin, Kaye, Marcuson, Masters, Regan, Restrepo, Shah, Smith, Stock, Strudwick, Toller, White, White and Wilkinson2019) recalls the different ways in which uncertainty can be expressed: inherent randomness, lack of knowledge, limitations in modelling, ambiguity, errors, human factors, and broader social and ethical factors. Consequently, best actuarial practice should recognise that, although there are uncertain, non-quantifiable scenarios, managers should focus on the decision of interest and take a proportional approach to the problem according to its importance, so as not to be detrimental to the business.

Some of the key points, based on actuarial advice, that enable better business decision-making in the face of these realities are: (i) the joint use of simple (heuristic) and complex models to identify and prioritise matters that are relevant to stakeholders, and to explain the assumptions and alternatives considered; (ii) the decomposition of the problems (where are you now?, where do you want to go?, how will you get there?) to gain a better understanding of the challenges faced by the entity, and to ensure that limitations do not prevent the entity making a good choice of the action to follow; and (iii) the adoption of prospective planning and resilient thinking to allow adaptability to respond to developments that are different from what was expected. Thus, actuarial modelling should focus on the decisions of interest so that the objectives can be achieved, while recognising that there are uncertain non-quantifiable scenarios.

5.2. Quantitative Strategic Risk Framework and Financial Modelling

The actuarial modelling approach is strategically positioned to contribute and innovate in the development of risk management tools. A proper segmentation of risks for all stakeholders, under the premise that no single risk measure exists, should be emphasized for the governance, management and regulation of the business; having multiple instruments that provide a sufficiently reasoned and practical perspective demonstrates the importance of actuarial management in terms of risk quantification.

Actuarial modelling provides useful and relevant information about the company´s financial performance, for example regarding its liability position and cash flow projections. Since members and managers in charge of commercial decisions must understand the current and future financial consequences of their choices for the entity, it is imperative that financial information be prepared consistently and transparently, especially with regard to risks with a long-term nature, and this information has to be understandable, relevant, comprehensive, comparable and, where possible, neutral (Gutterman, Reference Gutterman2002).

This confidence in financial modelling and reporting is possible, as actuarial teams tend to follow a rigorous code of professional conduct and actuarial standards of practice that allow the satisfactory achievement of minimum requirements. Thus, the joint work done in the actuarial, finance and accounting areas in the preparation and submission of financial statements, understood as one of the basic inputs for business decision-making, is an important one. Moving away from the stereotype of a team specialised in risks that is exclusively oriented towards statistics, chief actuaries can also demonstrate that the information they provide is sound, valuable, and necessary for the internal management and proper operation of the business entity; their vision offers robust financial information and key performance measures, sensitive to the internal/external context, risk assessment and changing circumstances.

It is worth noting that one of the virtues of actuarial management is the opportunity to have an interdisciplinary view of the risk map of the entity. Usually, lead actuaries are distinguished by the breadth of their knowledge, the trust others have in their comprehensive skills, and their knowledge of the workings and interconnections of virtually every department of a financial services company, especially in the insurance industry. Thus, working with others, the actuarial risk management approach can provide a comprehensive opinion of the organisational risk mapping and suggest which paths should be taken, merged or avoided altogether (DeAlmeida, Reference DeAlmeida2020).

With the implementation of Solvency II in the insurance industry, the relevance of actuarial management has become even greater, because capital allocationFootnote 6 has an important and challenging place in the agenda of corporate management bodies. Comprehensive risk quantification – which goes far beyond an accounting analysis – provides insights into how to allocate capital to reward shareholders while ensuring the stability, sustainability, and financial credibility of the company. To comply with the regulations, an actuarial function should also contribute to the definition of the limits of the risk-adjusted capital that can be invested to prevent the company from suffering shocks from devastating risks, facilitating the presentation of business options to the board in order to keep ongoing operations in line with the capabilities and characteristics of the company (Dacorogna, Reference Dacorogna2018).

Rech et al. (Reference Rech, Lu, Yan, Malhotra, Munza, Neuberger, Bin, Bohra, Bingham, Ruhm, Burchett, Shapland, Groeschen, Thiessen, Haria, Tse, Hussain, Wang and Larsen2012) discuss the positive implications for strategic management of using dynamic risk models, as senior executives often need to rely more on intuition than on systematic analysis when making tactical decisions. Core insurance activities such as pricing, reserving, underwriting, reinsurance, and investments need to be analysed in a comprehensive way, and they can be addressed using the mathematical modelling techniques provided by actuaries. These techniques have high-impact advantages and include: (i) information about the interaction of decisions in all operational areas of the company; (ii) a quantitative look at the risk and return trade-offs inherent in strategic opportunities; (iii) a structured process for monitoring and evaluating alternative plans, so that management can make more informed decisions; and (iv) the exploration of the possible financial effects of entering new markets or products. In the actuarial context, dynamic risk modelling can be thought of as a stochastic approach used to study the behaviour of organisational systems, revealing how structures, decisions and policies interrelate and how they affect the company’s financial results; this helps to identify profit opportunities, encourage efficient investment and avoid negative outcomes by giving an early understanding of the possible contingencies (Rech et al., Reference Rech, Lu, Yan, Malhotra, Munza, Neuberger, Bin, Bohra, Bingham, Ruhm, Burchett, Shapland, Groeschen, Thiessen, Haria, Tse, Hussain, Wang and Larsen2012).

Based on case studies, Adams and Jiang (Reference Adams and Jiang2020) point out that strategic decisions in the insurance industry need a high level of actuarial experience to avoid the underestimation of reserves and to improve profitability, because of the random nature of results and the complexities associated with estimating future losses; this type of company requires particular and constant supervision and in-depth advice from leading specialists with strategic mindsets at the board level. From a review of performance measures (net profit margin, asset performance and return on equity), financial solvency (solvency/leverage) and underwriting (loss ratio and combined ratio), their research shows that, for companies in the United Kingdom of different size, type of ownership and corporate governance structure, if the board has members with actuarial expertise, this generates a favourable impact on the performance of the insurer and the engagement of these members allows a better performance (Adams & Jiang, Reference Adams and Jiang2020).

Finally, from an organisational sociology point of view, Walter (Reference Walter2016) points out that the mathematical representation of risk from probabilities already incorporates subjectivity, morality and particular elements, and is not an objective perspective as is often thought – there is no ethical neutrality in mathematics. While quantitative risk models can provide a simplified representation of potential future outcomes based on a set of assumptions, a word of caution is also needed here. Appropriately, Bellis et al. (Reference Bellis, Lyon, Klugman and Shepherd2010) recall that risk management is much more than just models and that care should be taken not to lose sight of the inherent risks if the assumptions do not hold. Actuaries face challenging decisions with high uncertainty, and it is important to remember that, like any other professionals, they cannot always get things right.

5.3. Enterprise Risk Management with a Value-Based Approach

Nowadays, more and more companies are implementing Enterprise Risk Management (ERM) systems. An ERM system can be defined as a comprehensive and integrated framework that typically requires the identification, analysis, measurement, management, monitoring and disclosure of risks, with the aim of optimising the value to the organisation’s stakeholders. However, there are firms that still do not have a holistic and interdisciplinary technical approach for the assessment of risk–return trade-offs in decision-making (Segal, Reference Segal2011).

Over the last decade, the actuarial profession has contributed to the study and applicability of ERM, with a value-based approach, establishing risk governanceFootnote 7 and the corporate culture as key components. Actuarial management has the authority to influence and adjust the rules and the behaviour of individuals within companies, in order to determine how the different risks faced by the insurance industry are identified, understood, measured and mitigated (Tripp et al., Reference Tripp, Chan, Haria, Hilary, Morgan, Orros, Perry and Tahir-Thomson2008; Segal, Reference Segal2011). Some of the benefits of actuarial risk management are a strengthening and a deepening of the link between the business strategy and the risk strategy, through cash flow modelling, risk exposure and regulatory capital allocation, based on different simulated scenarios that provide senior management with the inputs required for its business decision-making (Halpert & Marlo, Reference Halpert and Marlo2007).

In the identification process, the actuarial management usually has, as a minimum, the following risk taxonomy: market (subdivided into capital, interest rate, inflation and exchange rate), credit, liquidity, operational (information systems, compliance, business processes, human resources, business continuity, outsourcing, distribution channels, etc.), legal, regulatory, strategic, reputational, and emerging (International Actuarial Association, 2016).

At the assessment stage, both inherent and residual risks are evaluated, and the evaluation includes a detailed description of the risk and its financial impacts. Risk measurement, with the extensive application of statistical and mathematical methods, enables senior management to allocate capital and measure performance better, by providing relevant quantitative information related to the materiality and proportionality of the risk and evaluating the magnitude of potential estimated losses (Tripp et al., Reference Tripp, Chan, Haria, Hilary, Morgan, Orros, Perry and Tahir-Thomson2008).

The actuarial analysis also includes stress and scenario testing, which help senior executives to understand the potential business outcomes of different strategic decisions; many of these calculations are also relevant in insurance companies for the ORSA (Own Risk Solvency Assessment) regulatory requirement. Here, actuaries can give support in the analysis of the company’s ability to continue in business, meet capital requirements and project future financial positions (Society of Actuaries et al., 2012). New risk metrics can also be created to determine the risk appetite based on tolerance statements (on multiple business planning horizons) and to add greater strategic value for smart decision-making and comprehensive management responsibilities, through better understood and communicated financial results (Halpert & Marlo, Reference Halpert and Marlo2007).

After the identification, measurement and analysis of risk comes the risk response stage. The actuarial recommendation starts from the following four basic categories, or a combination of them: avoid, accept, mitigate or share the risk, depending on the risk–return profile of the company (International Actuarial Association, 2016). Finally, the risk reporting, from an actuarial perspective, provides high-quality information on risk management, including its attributes such as opportunity, integrality, consistency, accuracy, auditing and prospects (Segal, Reference Segal2011). Thus, by applying this type of management with a value-based approach many organisations have been able to make effective business decisions with highly productive results, minimising the materialisation of the multiple risks present in the market (International Actuarial Association, 2016). They have also moved the ERM process away from a purely regulatory requirement to a more value-based advisory one.

Failure to follow appropriate ERM practices can have shocking consequences. Regarding the financial crisis that began in 2007 in the banking sector in the United States, with its devastating consequences around the globe that we all know about, Segal (Reference Segal2011) concluded that, contrary to popular belief, banks did not generally follow an adequate ERM programme. In the same way, Bellis et al. (Reference Bellis, Lyon, Klugman and Shepherd2010) state that, during the crisis, ERM was not as effective as it should have been for some insurers, referring to the collapse of the giant insurance company American International Group (AIG); they also argue that even insurers with advanced risk management practices did not always have appropriate ERM governance structures. Positive impacts on the future of ERM are expected from the financial crisis. New regulations will accelerate the adoption of ERM programmes, and companies in all sectors, not just in the financial sector, have begun to assess their ERM activities in order to enhance them (Segal Reference Segal2011).

6. Discussion on the Future Importance of Actuarial Management in Data Science

Historically, actuaries have been regarded as experts in risk management, primarily in the insurance market. In the late 1980s, a first classification of actuaries was offered in the literature; since then, the classification has evolved, and it currently includes five types or generations of actuaries. The first kind of actuary, from the seventeenth century, focused on life insurance and used deterministic methods. The second kind, in the early twentieth century, was interested in non-life insurance and used probabilistic methods. The third kind, in the 1980s, developed skills in investment and financial economics and applied stochastic processes to the valuation of assets and liabilities. The fourth kind, from around 2005, are those actuaries working in ERM. Recently, in 2016, a new generation of actuaries emerged; these are actuaries with capabilities in big data and analytics (Chan & Devlin, Reference Chan and Devlin2016).

This so-called fifth generation of actuaries has recently been noticed in an era marked by significant computational developments, advances in the technology of big data, data mining and deep learning algorithms (Gan & Valdez, Reference Gan and Valdez2016; American Academy of Actuaries, 2018; Panlilio et al., Reference Panlilio, Canagaretna, Perkins, du Preez and Lim2018; Diana et al., Reference Diana, Griffin, Oberoi and Yao2019). The current availability of huge amounts of data, both structured and unstructured, in nearly all industries, together with innovative techniques, has begun to provide new perspectives for decision-making. Data analytics has been classified into the following four categories, and actuaries in the insurance industry have historically performed well in the first three of them: (i) descriptive (what happened?), (ii) diagnostic (why did it happen?), (iii) predictive (what will happen?), and (iv) prescriptive (how can we make it happen?). All these advances, although very important for actuarial sciences, also require accountability frameworks and new roles in ethics and algorithm and data auditing (Institute and Faculty of Actuaries, 2018).

Likewise, the challenge in the short term will be the continuous ethical review of the development and application of artificial intelligence algorithms, and compliance with the fundamental pillars of actuarial science for customer treatment (responsibility, transparency, predictability, auditability and incorruptibility), thus avoiding negative effects on certain social, racial or religious groups or those with other characteristics that are protected by equality laws (Raden, Reference Raden2019).

All this has broadened the field of action for actuarial leadership, and actuarial societies around the world are training actuaries in modern methods and models for analysing data. Actuaries are well positioned to lead teams of statisticians, data scientists, operations researchers, and information engineers, among those in other related careers, employed in multidisciplinary data teams in all kinds of different industries besides the financial sector. In addition, the high standards of conduct, practice, technical competence, and qualifications of the actuarial profession provide essential elements for fulfilling the profession’s responsibility to its key stakeholders and enabling reliance by both consumers and regulators (American Academy of Actuaries, 2018).

Bearing in mind that artificial intelligence – and machine learning – will increasingly take over part of the traditional actuarial work, it is important from a managerial point of view to strengthen skills in the generation of strategic information for even better business decision-making processes. It is not only new programming and modelling skills that are now required in a complex and interconnected world but also more creative solutions and disruptive innovations in the face of current challenges.

7. Conclusions

This research paper presents a systematic review of the literature on the relevance of actuarial management in insurance business decision-making in the twenty-first century. In a world with increasingly complex, interrelated and more dynamic challenges, the corporate strategy needs to rely on the best information available. Technical strengths, critical thinking, a holistic view of risk and commercial insight, as well as the constant reinvention and robustness of the actuarial profession have been shown to be ideal for the continuous generation of added value in the corporate world, especially in the insurance industry.

Although risk management has been around for many decades, recent events such as the 2007 global financial crisis have made companies aware of the importance of managing risks properly; this is required across all sectors, in order, among other things, to improve the understanding, measurement, and communication of risks and their financial implications. The reputation of actuarial professionals, who play key roles in ERM systems, arises from a number of reasons, including their widely recognised learning derived from research, their advanced knowledge in quantitative techniques complemented with practical experience, and their adherence to high ethical and technical standards, with formal disciplinary and qualification processes.

After formally carrying out the steps of the methodological process for the review of the literature, the paper discusses three frameworks covering the significant contributions of actuarial management in the making of business decisions, mainly in insurance, and thus answers the objective of this research.

The first of these frameworks, related to the actuarial cycle control and uncertainty management, shows the importance of having a scheme that addresses external forces, economic conditions, and the business environment, in a professional and iterative model based on the following triad of actions: the identification and specification of the problem, the development and implementation of the solution, and the monitoring of and response to the results. This, when coupled with a clear understanding of risk and uncertainty, provides decision makers with greater dynamic capacity to thrive in changing environments.

The second framework refers to quantitative strategic risk and financial modelling. The actuarial approach provides first-class capabilities that stand out in all stages of risk quantification, starting with the design, construction, testing, and interpretation of financial models that clearly recognise their assumptions and limitations and allow for different event paths. This perspective offers excellent tools to support and guide the decision-making of senior management in a holistic, consistent and structured way.

The third topic corresponds to the value-based approach of the actuarial profession to ERM. It offers a robust yet practical approach for quantifying not only financial and strategic but also operational risks that can be adopted in all kinds of businesses. Nowadays, a well-defined ERM infrastructure, a process cycle, a risk appetite, metrics, governance, and clear communication that properly recognises correlations and risk–return trade-offs are required to support better decision-making. Additionally, and not yet fully unveiled, there are the contributions of the actuarial profession to data sciences. With appropriate training in the latest technological tools and modern analytic capabilities, actuaries can have the edge and step up to take on key data management roles in different industries, besides insurance and banking.

All these topics show the useful, intelligent, and significant contributions that the actuarial vision can offer to a company’s senior management team. In the face of challenging environments, decision-making processes increasingly require innovation, flexibility, integrity, robustness, fluency, effective communication, and adaptability, among other key factors. In addition to their highly specialised quantitative skills, there is an inevitable requirement for actuaries in management roles to develop soft leadership and business skills. This would not only help the development of better business awareness and knowledge but would also provide greater influence, a better vision from the managerial sciences and ideal and effective communication with the company’s higher management (Gribble & Traverso, Reference Gribble and Traverso2018). Of course, it is also essential to recognise that an actuary is often a team player who is required to collaborate with others to achieve business objectives and is not exempt from human error.

Finally, given the comprehensive view and proven benefits of actuarial management, a call is made by the authors for more direct participation – at least in their native country of Colombia – by actuaries in public policy discussions and decisions, in reforms of different public systems (such as pensions and health), in the monitoring and evaluation of the impacts of public policy, in fiscal sustainability analyses, in macroeconomic public credit studies, and in the design of information systems, among other things.

Acknowledgements

This research work is derived from an MBA thesis by Oscar Espinosa, who would like to express his very great thanks to Jorge Chaparro, Roy Goldman, Jeyaraj Vadiveloo, Eduardo Melinsky, James Glickman, Jules Gribble, Sim Segal, Dale Hall, Andrew Rallis, Aaron Bruhn, Mervyn Kopinsky, Gabriela Dieguez, Christian Walter, Hansjoerg Albrecher, Christian Mora, Rigar Santiago, Diego Torres, Wilson Mayorga, Santiago López and the peer reviewers of the journal for their valuable advice, comments, and suggestions on different sections of this research.