1. Summary of Paper and Conclusions of the Working Party

‘While money can’t buy happiness, it certainly lets you choose your own form of misery’, Groucho Marx.

This paper is the culmination of the work of the Financial Literacy Working Party, which was set up to consider the existing level of financial literacy among the general public, the most useful financial knowledge and effective public and private efforts to improve financial literacy and, finally, a strategy to increase the level of financial literacy of the general public. Throughout the paper, we focused mainly on the UK, but have considered international perspectives where appropriate.

First, in section 2, we research the existing level of financial literacy in the UK population. Various sources indicate that the baseline level of financial literacy is very low; large numbers of people, from all sections of society, are not planning ahead or saving sufficiently for retirement or a rainy day; over-indebtedness is rife and many people take on financial risk without realising it because they buy financial products that are not suitable for their needs. Unless necessary steps are taken to improve levels of financial literacy, we are storing up trouble for the future, but even if levels of financial literacy can be significantly improved, this may not be sufficient to ensure better customer outcomes from financial products.

We then discuss in section 3 some key mechanisms for improving financial literacy including financial education in schools, vocational training, and educational and informational tools. Our research suggests that the amount of time spent on financial education in schools is limited and has questionable impact. Furthermore, despite the plethora of internet tools and apps that are available to support budgeting and savings, provide advice on borrowing and debt, and general financial education, the level of financial literacy remains stubbornly low. We propose additional methods of improving financial literacy and protecting vulnerable consumers. These methods include special treatment for complex products, product certification, introduction of a fiduciary rule for advisers and introducing a duty of care on financial firms.

In section 4, we introduce five key principles of financial literacy which are: plan your spending, plan for emergencies, plan your borrowing, plan your savings and plan for advice. The suggestion of the working party is to shorten and simplify these five principles into a one-page document that will be available on the Institute and Faculty of Actuaries (IFoA) website with the purpose of stimulating interest and circulation of financial literacy principles, and to add our voice as the actuarial profession to promote the concept of financial literacy to the wider public.

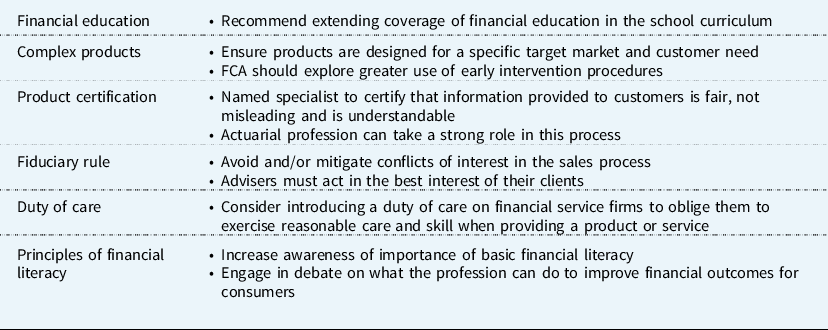

The implications of the above proposals to improve financial literacy are then discussed in section 5. First, we support the House of Lords Select Committee on Financial Exclusion’s recommendation that financial education should be added to the primary school curriculum. We support the view that every child should be able to leave school with a good knowledge and solid understanding of how to manage money in adult life and how to make positive money choices. Second, we consider special treatment for complex retail financial products, including greater use of regulatory intervention procedures and product certification. Third, we discuss the introduction of a fiduciary rule for advisers. Fourth, we present the benefits of introducing a duty of care and its potential implications for firms and customers.

Finally, we move on in section 6 to present our conclusions which are summarised above in Table 1.

Table 1. Conclusions

We want to make it clear to readers that there is no “silver bullet” to solve all the issues that we raise. This is an incredibly complex area, with multiple stakeholders and a constantly changing environment.

Our key goal has been to demonstrate how levels of financial literacy could be improved if the ideas and conclusions of the research are followed. A secondary goal that emerged from our initial research was to consider additional mechanisms that would protect less-sophisticated, vulnerable customers and improve their understanding of insurance products (in particular). There are a number of areas where more research could be conducted. These are the concepts of fiduciary rules for advisers and a duty of care on financial firms; the role for a stronger Government or industry-sponsored advice service; closing the gap between women’s and men’s financial literacy; improving financial literacy for vulnerable customers; and the consequences of the responsibility for financial security being increasingly shifted to consumers from the state and employers. We have commented on vulnerable customers, but vulnerability is a broad term and there is much more to add. The working party believes that this is a research topic in and of itself. We note finally that the last area on the responsibility for financial security being increasingly shifted to consumers is a separate IFoA topic under the banner of The Great Risk Transfer project.Footnote 1

2. Background

2.1. Objectives of the Working Party and This Paper

As the Financial Literacy working party, we were set up with the objectives of looking at:

-

The existing level of financial literacy among the general population

-

The most useful and relevant knowledge and information that the public would need to have to make more informed financial decisions

-

The most effective existing public and private efforts to improve financial literacy

-

A strategy to increase the level of financial literacy of the general public

As a working party, our key goal has been to demonstrate how financial literacy could be improved if the ideas and conclusions of the research are followed. In this paper, we present our preliminary thoughts and recommendations and we would welcome feedback and debate on this. Some of the recommendations will cost something to implement and should therefore be supported by cost-benefit analyses that would weigh these costs against the potentially larger benefits to customers and society.

2.2. Why This Is Still an Important Issue

To understand why the questions mentioned above are so important, it is worth highlighting the scale of the problems that we face.

2.2.1. Financial literacy base level

According to the Financial Services Authority (FSA, 2003), there are low levels of understanding and confidence across a range of financial needs:

-

Research for the Financial Services Consumer Panel (FSCP) shows that many consumers do not understand which products are linked to the stock market and what the term “equity” means.

-

Two-thirds of consumers think that financial matters are “too complicated for them” and that they do not know enough to choose suitable financial products.

The FSA’s 2006 report Financial Capability in the UK: Establishing a Baseline (FSA, 2006a) concluded that:

-

Large numbers of people, from all sections of society, are not taking basic steps to plan ahead, such as saving sufficiently for their retirement or putting money aside for a rainy day.

-

The problem of over-indebtedness is not that it affects a large proportion of the population, but that when it strikes, it is often severe and that many more people may find themselves in trouble in an economic downturn.

-

Many people are taking on financial risks without realising it because they struggle to choose products that truly meet their needs.

-

The under-40s, on whom some of the greatest demands are now placed, are typically much less financially capable than their elders, even allowing for their generally lower levels of income and experience in dealing with financial institutions.

IFoA Past President Jane Curtis stated in 2012 that “Financial literacy for most of the UK remains poor. We have a large savings gap and a lack of trust in the financial services industry. These problems are exacerbated by gaps in the public’s economic knowledge, including how much is required to provide their expected pensions, and confusion over how financial products work.” (Curtis, Reference Curtis2012)

Research by the Money Advice Service (MAS, 2016) indicated that, despite financial education being on the school curriculum at least at secondary level across the UK, only 40% of children aged 7–17 say they have learned about managing money at school or college, and this is consistent across all age groups. Similarly, only 41% of 16- to 17-year-olds are able to correctly read a payslip and 18% are unable to correctly identify how much was in a bank account when looking at a bank statement.

A more recent report from the Financial Conduct Authority (FCA) showed that one in six (17%) of UK adults had very low financial capability, defined as those who rate their confidence in managing money or their knowledge about financial matters as 0–3 out of 10, or who disagree strongly that they are confident and savvy consumers when it comes to financial services and products (FCA, 2017).

2.2.2. Consequences of poor financial literacy

Lack of financial capability has consequences for consumers, the industry, other service providers and, indeed, society as a whole (Hasler et al., Reference Hasler, Lusardi and Oggero2018; Anderloni et al., Reference Anderloni, Bacchiocchi and Vandone2011; Lusardi & Mitchell, Reference Lusardi and Mitchell2014). Few would dispute that it is a significant contributor to all of the following (FSA, 2003).

For Consumers

Losing money

FSA research shows that lack of understanding of how to shop around leads to consumers losing out.

Not understanding or meeting needs

Lack of financial capability increases the risk that consumers will mis-buy financial products, i.e. they will make unsuitable purchases.

Lack of financial understanding also increases the risk that consumers will buy products which would not meet their needs or may not make sufficient provision to meet those needs.

Feelings of helplessness

Research undertaken by The All Party Parliamentary Group (APPG) on Financial Education for Young People (Young Enterprise, 2016) has indicated that many adults lack the knowledge and skills to thrive in an increasingly complex financial landscape. Four in ten adults are not in control of their finances, with 21 million families having less than £500 in savings to cover unexpected bills. Around eight million have problems with debt. Furthermore, two in three consumers surveyed by the FSCP felt that financial matters were too complicated for them. This feeling of helplessness can lead to consumers not taking actions they need to take.

For the Financial Services Industry

Lack of consumer confidence in markets and in firms

Consumers who do not understand products or who feel that they have bought, or been sold, something unsuitable will lose confidence in the individual firms with which they deal and possibly with the market as a whole. This may mean that firms are losing customers or potential customers.

Increased costs and stronger regulatory intervention

Lack of financial understanding on the part of consumers, leading to mis-buying and increased vulnerability to mis-selling, means higher costs for the industry. Substantial costs have been incurred by firms responsible for past mis-selling, and the costs of handling complaints when consumers have bought something which does not meet their needs are also considerable. Furthermore, lack of financial capability has meant relatively high levels of regulatory intervention to protect consumers (FSA, 2003).

IFoA Past President Jane Curtis stated that “many consumers continue to buy the wrong products – or the right products at the wrong time. They make poor decisions about pensions, sometimes make no decisions at all”. (Curtis Reference Curtis2012)

2.2.3. Need for financial literacy

Regarding improving financial literacy, the FSA stated in 2003 that “Never has the need been so great or so urgent”. (FSA, 2003)

The benefits of taking action to improve financial literacy are clear (FSA, 2006b).

-

The combination of increasing personal responsibility and lack of financial capability means that action must be taken.

-

If people become more financially capable, they can make their incomes go further: for example, shopping around helps them spend less in interest when they borrow and earn more when they save. They can assess how to balance current spending with saving for the future. They can protect themselves against the unexpected through savings and insurance. They are better placed to reach retirement with the resources they need for the standard of living to which they aspire.

-

Financially capable consumers know when and how financial institutions can help them. They are less prone to buying products that do not suit their needs and more inclined to engage proactively with the financial services sector.

-

And, because a capable customer is a less vulnerable customer, the FSA will, over time, have less need to intervene with detailed rules in the retail markets.

Personal finance education, taught in a compelling and practical way, can make all the difference later in life. Furthermore, a population well-served in this way and well-versed in personal finance will be one that is more capable and self-reliant. People who understand their financial circumstances are more likely to make sensible choices and adequate provision for their futures (FSA, 2004).

Improving financial literacy should be positive for the Life and Pensions industry. According to Jane Curtis: “a more financially literate consumer is more likely to buy the right products at the right time for the right job and to avoid being mis-sold to or failing to make sufficient financial provision for his or her future” (Curtis, Reference Curtis2012). Research suggests a positive relationship between financial literacy and insurance demand (Li et al., Reference Li, Moshirian, Nguyen and Wee2007; Cappalletti et al., Reference Cappelletti, Guazzarotti and Tommasino2013; Kubitza et al., Reference Kubitza, Hofmann and Steinorth2018). Further research indicates that by every measure and in every sample examined, financial literacy is a key determinant of retirement planning (Lusardi and Mitchell, Reference Lusardi and Mitchell2009), a conclusion that is supported by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) (Aegon, 2018; OECD, 2019).

The APPG have concluded that: “Understanding how to manage money well remains a key life skill that is required for all aspects of adult life. It allows individuals to make informed financial decisions on a day-to-day basis – from buying products at the supermarket to choosing a new electricity provider – and encourages them to save for their future and any unexpected “shocks” in their life.”

The APPG further concluded that there is a need to improve financial literacy training for teachers. Their own research has found that only 17% of secondary school teachers have personally received, or are aware that a colleague has received, training or advice on teaching financial education. This is despite the fact that 58% would like to receive more training in this area (Young Enterprise, 2016).

2.2.4. International perspective

According to the OECD (OECD, 2017a; OECD, 2017b), around one in four students in the 15 countries and economies that took part in their latest OECD Programme for International Student Assessment test of financial literacy is unable to make even simple decisions on everyday spending, while only one in ten can understand complex issues, such as income tax. Most people do not have even basic financial knowledge (OECD, 2017c).

At the launch of the report, OECD Secretary-General Angel Gurría stated that: “Young people today face more challenging financial choices and more uncertain economic and job prospects given rapid socio-economic transformation, digitalisation and technological change; however, they often lack the education, training and tools to make informed decisions on matters affecting their financial well-being”. (Gurría, 2010).

Standard and Poors (S&P) have surveyed financial literacy levels of 150,000 people in over 140 countries (S&P, 2015). The survey consists of four questions included in the Gallup World Poll Survey. The questions include one on risk diversification, one on inflation, one on interest paid on a loan and one on interest paid by banks. We understand that the relevance of such standard questions may be coloured by local practices and culture. One obvious example would be that questions on interest rates may not be highly relevant to large sections of the Islamic world. Despite this, the working party believes that this is an important survey given its large sample and broad geographical scope and we include it to provide a global context.

S&P stress that without an understanding of basic financial concepts, people are not well equipped to make decisions related to financial management. People who are financially literate have the ability to make informed financial choices regarding saving, investing, borrowing and more. The highlights of their 2018 survey indicated:

-

Low levels of financial literacy around the world

-

Numeracy and inflation are the most understood concepts

-

Risk diversification is the least understood concept

-

Women’s financial literacy levels are lower than men’s. This gender gap is found in both advanced economies and emerging economies. Women have weaker financial skills than men even considering variations in age, country, education and income

-

The young are a vulnerable group and an important target for financial education programmes

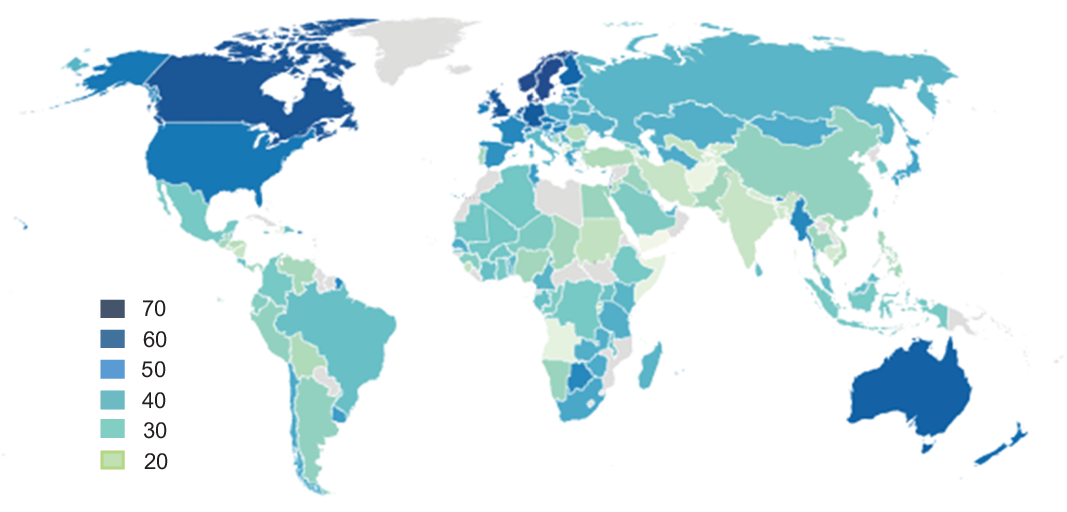

The survey concluded that only 33% of adults worldwide are financially literate. This means that around 3.5 billion adults globally, most of them in developing economies, lack an understanding of basic financial concepts. These global figures conceal deep disparities around the world. Figure 1 and Map 1 below show these disparities, particularly between advanced and emerging economies (S&P, 2015).

Figure 1 Wide variation in financial literacy around the world (% of adults who are financially literate).

Map 1. Global variations in financial literacy (% of adults who are financially literate).

In the US, a survey carried out by the Financial Industry Regulatory Authority (FINRA) Investor Education Foundation indicated that only 37% of adults were able to answer at least four of five financial literacy quiz questions correctly, down from 39% in 2012 and 42% in 2009. Furthermore, only 39% report having ever tried to figure out how much they need to save for retirement, and over half worry about running out of money in retirement (FINRA, 2016).

Every 2 years, the Council for Economic Education (CEE) conducts a comprehensive investigation into the state of K-12 economic and financial education in the US. K-12 broadly corresponds to education from kindergarten through to high school. The 2018 Survey of the States (CEE, 2018) shows that there has been little increase in economic education in recent years and no growth in personal finance education.

In conclusion, several large-scale surveys indicate a low level of financial literacy worldwide, with little evidence to show that this is being addressed at young ages through increased or improved education and training.

2.3. Improving Financial Literacy Is Not a Silver Bullet

International research indicates that financial literacy and capability interventions can have a positive impact both generally (Kaiser & Menkhoff, Reference Kaiser and Menkhoff2017; Lusardi, Reference Lusardi2019) and in specific areas including increasing savings propensity and promoting financial skills such as record keeping (Miller et al., Reference Miller, Reichelstein, Salas and Zia2014). However, Professor of Law, Lauren E. Willis has argued against improving financial literacy as a silver bullet to improve customer outcomes from financial products (Willis, Reference Willis2008).

“As products have become increasingly complex, consumers’ inability to understand them has become increasingly apparent, and the consequences of this inability more dire. In response, policymakers have embraced financial literacy education as a necessary corollary to the disclosure model of regulation. This education is widely believed to turn consumers into “responsible” and “empowered” market players, motivated and competent to make financial decisions that increase their own welfare. The vision is of educated consumers handling their own credit, insurance, and retirement planning matters by confidently navigating the bountiful unrestricted marketplace.

Although the vision is seductive, promising both a free market and increased consumer welfare, the predicate belief in the effectiveness of financial literacy education lacks empirical support. Moreover, the belief is implausible, given the velocity of change in the financial marketplace, the gulf between current consumer skills and those needed to understand today’s complex non-standardised financial products, the persistence of biases in financial decision making, and the disparity between educators and financial services firms in resources with which to reach consumers.

Harboring this belief may be innocent, but it is not harmless; the pursuit of financial literacy poses costs that almost certainly swamp any benefits. (Lipsey & Lancaster, Reference Lipsey and Lancaster1956) For some consumers, financial education appears to increase confidence without improving ability, leading to worse decisions. (Questis, 2017) When consumers find themselves in dire financial straits, the regulation through education model blames them for their plight, shaming them and deflecting calls for effective market regulation. Consumers generally do not serve as their own doctors and lawyers and for reasons of efficient division of labor alone, generally should not serve as their own financial experts. The search for effective financial literacy education should be replaced by a search for policies more conducive to good consumer financial outcomes.”

The authors agree with Professor Willis. In order to improve consumer financial outcomes, financial education must be part of a series of measures that help consumers make choices in a context that can realistically be navigated.

Given the evidence that we have presented in earlier sections on the low levels of financial literacy and how they are scarcely improving, these views are worth considering seriously. If consumers are never going to be savvy, is it unreasonable to base consumer legislation on the assumption that they are (WP, 1989; Kahneman, Reference Kahneman2003; Janusz, Reference Janusz2005; DJ, 2007; Reifner, Reference Reifner2007; Cialdini, Reference Cialdini2008; Kroszner, Reference Kroszner2008; EC, 2016; G30, 2019).

In this context, it is interesting to note that Section 1C of the Financial Services and Markets Act 2000 (FSMA) clearly states that: “In considering what degree of protection for consumers may be appropriate, the FCA must have regard to…the differing degrees of experience and expertise that different consumers may have” (FSMA, 2000).

Given the low level we have identified, perhaps some products should never be sold at all. Product approval or certification has been anathema to the UK Financial Services Industry. Is it time for a change?

3. Mechanisms for Improving Financial Literacy

Following on from section 2, we believe that low levels of financial literacy have ultimately occurred through a combination of:

-

Poor or non-existent financial education

-

Perceived lack of importance of the topic

-

A failure to make the subject interesting

-

External market forces

3.1. Financial Education, in Schools and Vocational Training

Research shows that students exposed to economic and financial education are more likely to display positive financial behaviours (CEE, 2016; EBA, 2020). The House of Lords Select Committee on Financial Exclusion (HoL, 2017) has further concluded that improving financial literacy is crucial for tackling financial exclusion, recommending that financial education should be added to the primary school curriculum. However, they go on to say that this alone will not be sufficient to enhance the level of financial education provision in schools. According to Gateshead Council (GC, 2016), “Financial education must start in primary schools to allow the simple basics of money matters to be taught, such as how much things cost, how to save and why saving is a positive thing. From primary school to leaving secondary school the financial education curriculum should move with age appropriate content ensuring all topics are covered…”. Additional research supports this view, indicating that some behaviours and attitudes towards money are formed as early as primary school age (Moffitt, Reference Moffitt2010; Whitebread & Bingham, Reference Whitebread and Bingham2013).

Financial literacy is heavily linked to overall numeracy skills, though it is noted that individuals would also need reasonable literacy skills. Where students have poor literacy skills, it is likely to restrict their learning across all subjects.

Confidence in numeracy and other mathematical skills is listed as a “precondition of success across the national curriculum” (DFE, 2014). Whilst mathematics is recognised as “necessary for financial literacy and most forms of employment”, concepts relating to financial literacy are mainly covered by the citizenship curriculum, specifically:

-

the functions and uses of money, the importance and practice of budgeting, and managing risk.

-

income and expenditure, credit and debt, insurance, savings and pensions, financial products and services, and how public money is raised and spent.

Whilst the presence of financial literacy in the curriculum is welcomed, its rollout and overall efficacy are debatable (see e.g. MC, 2019). According to the Young Persons’ Money Index, which is an annual survey that tracks the take-up of financial education in schools in the UK, 64% of students say they have access to financial education compared to only 29% in 2015 (YPMI, 2019). However, for those schools following the national curriculum, the choice to cover financial literacy within citizenship results in limited attention on the topic (Conversation, 2018). Whilst the contents of the citizenship curriculum are mandatory, the subject does not have to be discreetly timetabled. It can be integrated into subjects such as Personal, Social and Health Education or other humanities subjects and not typically get more than an hour per fortnight. Furthermore, there is no form of examination for citizenship, and the subject is not taught by specialist teachers (MC, 2019). Typically, teaching resources would be allocated to fill timetables once all other classes had been assigned. This is an important area for improvement, as evidence from several projects run in UK schools indicates that providing specialist financial education training to teachers is valuable and has a clear positive impact for teachers and students, in particular improving outcomes across students’ mindset and skills (What Works Fund, 2018). Finally, the increasing number of academies has reduced the number of schools following the national curriculum, meaning that financial literacy is not actually mandatory for 46.8% of pupils (DFE, 2019; see also MyBNK, 2020).

Some of the knowledge needed for an individual to be deemed financially literate could be considered too advanced for secondary school students. An awareness of financial literacy is a skill that is a lifelong requirement that will vary for individuals at different life stages, so the information and decision-making needs shift over time and information/education needs to be targeted and age appropriate. Financial decisions that people need to make do not get easier with age, and the stakes may be higher for older individuals with higher net worth and where the financial decisions are more complex (Bhutoria et al., Reference Bhutoria, Jerrim and Vignoles2018).

There is clearly a need for some new and creative thinking to give the whole financial literacy debate more impetus and focus. So, for example:

-

Is there an expanded role that the public service broadcasters such as the BBC can play? (BBC, 2020). For example, this could involve building on existing programming, such as all the “how to shop better by buying own brand” type programmes, extending this out to financial planning. They could have a more positive agenda to contrast with the Watchdog-type scam warnings (BBC, 2019; Times, 2019; Which, 2019).

-

There could also be an increased role for National Savings and Investment (NS&I, 2019) with an expanded range of basic but “safe” products and greater promotion in all media forms. Consider, for example, the high levels of engagement achieved by the launch of the National Lottery.

-

And similarly for other mainstream online and offline media (for example, the Daily Mail/Mail online, the Sun) and social media outlets. On the latter, should the financial world (regulators, firms, trade bodies) be looking for YouTube/Instagram “celebrities” to endorse the need for financial services/insurance etc, and potentially publicise specific kite-marked products?

-

If other players rowed in behind some core messages on a consistent basis over time, that would amplify these messages (e.g. regulators, industry bodies, credit unions, citizens advice, government, employers’ organisations, 3rd sector bodies, professional bodies). It is all about tell, tell, tell and tell again. What is the best way to achieve that coordinated activity on an ongoing and consistent basis? Which body/ies can champion this? Is a new body needed? How can this be promoted higher up the government’s agenda? Should there be a minister for financial literacy and personal financial responsibility to be a focal point for getting people to proactively take on the responsibilities for their own financial security that are being increasingly shifted to them from the state and employers – and to help equip them to do this?

3.2. Educational and Informational Tools

3.2.1. Books and the internet

There are several short books that address financial literacy and education at a basic level (Fox, Reference Fox2016; Gardner, Reference Gardner2016; Lewis, Reference Lewis2005; Matthew, Reference Matthew2018; Straube, Reference Straube2011; Tapper Reference Tapper2019). However, for most people, it seems likely that the Internet will be the main resource as regards education and information about understanding personal finances (OECD, 2017d).

The European Banking Authority (EBA) has published a report summarising 123 financial education initiatives delivered by authorities within the European Union (EBA, 2020). In general, most of what is available on the consumer or government backed websites is good and consistent with the principles set out in this paper. This may indicate that the main challenge is not in determining and agreeing principles but lies in ascertaining why these principles are not more widely grasped and accepted.

It seems likely then that the challenge may lie in one of three areas:

-

The level of general financial literacy is so low that many find even the basic concepts expressed to be beyond their understanding.

-

Not enough work is being done to promote those websites that are working in this area and/or there is a lack of consistency in the message.

-

The weight of advertising from those with a commercial axe to grind serves to obscure not-for-profit websites and/or the sheer volume of competing claims in this marketplace causes confusion and lack of trust.

Please refer to Appendix 1 for a sample of websites that support financial literacy that have been reviewed by the working party.

3.2.2. Budgeting Apps

Keeping a budget is the key starting point in managing money (Step Change, 2015; BBC, 2016; MSE, 2016; U.S. News, 2017; MAS, 2019; GSM, 2020; SAM, 2020). There are a number of apps available to download to support budgeting and savings, the majority of which are free of charge.

Apps such as Yolt, Money Dashboard, Oval Money, Bean and Emma combine information from all your bank, savings and investment accounts, giving a single place to view data. You can then use the app to set budgets against different categories (e.g. bills, groceries, eating out) and track your spending against these.

Apps like Cleo go one step further and use artificial intelligence to automatically save money for you when you can afford it, notify you if you are about to go into your overdraft and can even let you know how much you can spend on lunch.

Other apps can also encourage you to save, such as Moneybox which will round up any purchases to the nearest pound, investing the spare change.

There are also several digital-only banks (e.g. Monzo, Starling Bank, Revolut), which offer similar functionality to the above apps, alongside their own personal bank accounts. Banking with these providers can help you see what you are spending and saving more easily, via their digital platforms.

3.3. Other Methods of Improving Financial Literacy and Protecting Vulnerable Consumers

The FCA defines a vulnerable customer as: “someone who, due to their personal circumstances, is especially susceptible to detriment, particularly when a firm is not acting with appropriate levels of care” (FCA, 2015a).

The sessional paper “How can we improve the customers’ experience of our life products?” discussed options for improving customer outcomes from their insurance products (Barnard et al., Reference Barnard, Francis, Hussain, Jumanca and Zhang2018). We will not recap all of the proposals and discussion points, but will focus on some ideas that could help protect less knowledgeable and more vulnerable customers and improve understanding of insurance products.

3.3.1. Special treatment for complex products

Complex financial products can be particularly difficult for retail customers to understand (OECD, 2010; Rutledge, Reference Rutledge2010; EP, 2014). Chair of the Financial Services Consumer Panel (FSCP) Wanda Goldwag has spoken about a plethora of products in the market that consumers do not understand and advisers fail to properly explain. She said: “I think there has been a great deal of mis-selling of products, but also a great deal that are far too complex and not well explained. Including being not well explained by advisers” (Goldwag, 2019). This view is supported by research from the FCA which found that investors’ understanding of structured deposits is limited (FCA, 2015b). According to the FCA, innovation in retail financial markets has led to increasing product complexity over the past two decades, but there is little evidence of a comparable increase in consumers’ financial capability. Furthermore, financial experts and those with higher education were only slightly more likely to answer comprehension questions correctly than non-experts and less educated subjects.

The Markets in Financial Instruments Directive (MiFID II) (EU, 2014) requires investment firms to act in the best interest of their clients and strengthens product governance by requiring that firms should only design and bring to the market products that meet the needs of the identified target market. The Insurance Distribution Directive (IDD) (EU, 2016) introduces similar requirements on insurance distributors. In order to recommend products that are suitable for a customer, both MiFID II and IDD require firms and intermediaries to obtain the necessary information regarding the customer’s knowledge and experience in the investment field, their financial situation and ability to bear losses.

The FCA goes potentially further than this by already placing restrictions on the distribution of certain complex investment products (FCA, 2019a), particularly those with geared, non-linear or binary outcomes. However, we see very complex products still being marketed to retail customers, resulting in poor outcomes and regulatory intervention (alpha architect, 2019; WSJ, 2019). The working party recommends that the FCA should make greater use of early intervention procedures (FCA, 2018a). For example, in October 2014, the FCA used its powers to stop the sale of contingent convertible securities for retail customers, which is estimated to have prevented customer detriment in the range of £16m to £235m (FCA, 2014).

3.3.2. Product certification

We briefly raised the topic of product certification in section 2.3 in the context of low financial literacy and complex financial products, and we see a role for the actuarial profession in providing this certification. A named actuarial, risk or compliance specialist of sufficient standing should be required to certify that product terms and conditions and marketing information presented to customers is fair, not misleading and should be understandable to the target market (Brownsword et al., Reference Brownsword, Micklitz, Niglia and Weatherill2011). For many mass insurance products, the target market would be made up of the “person in the street”, who we can infer has a relatively low level of financial literacy.

This product certification should ideally be a principle-based requirement, rather than based on a set of fixed rules that would potentially need to be amended and modified over time as markets, distribution, customer needs and products evolve. The named specialist would be responsible for the framework for evidencing and substantiating the certification and would need to be able to defend such certification if challenged to do so. We could imagine that certain products that meet specific requirements for simplicity and understandability could be kite-marked, which would allow an easier product certification based on a “safe harbour” concept for such products.

One advantage of such developments could be that such simpler and more understandable products could mitigate the need for expensive financial advice. This is a topic that we explore in the next section.

3.3.3. Role of advice

Our research puts a lot of store on the role of advice (and the paper suggests strengthening fiduciary duty, which is sensible). But, advice channels are costly to access (MSE, 2019; CA, 2020); it is hard to know where to look for advice (who can you trust?) and it involves exposing your own personal situation/finances, which may put off some people. So, there are lots of barriers to accessing advice, and perhaps, the focus should be more on guidance channels where common-sense information can be sourced, for example through the workplace, from credit unions and trades unions and affinity groups. In the UK, building on the inroads stakeholder pensions have made may be a good building block via employers (PAS, 2019).

This point is strengthened by the emergence of an “advice gap” in the UK market since the Retail Distribution Review (RDR). For example, Cass Business School recently concluded that as a result of the RDR, a UK investor with less than £61,000 in investment funds is no longer commercially viable for investment advisory services (note that approximately 75% of the UK adult population would have less than this amount to invest, Clare, Reference Clare2013). Is there a role for a stronger Government or industry-sponsored advice service to cater to the needs of this market segment? Would the ideas promulgated in section 3.3.2 help mitigate this advice gap through simplified delivery and advice mechanisms coupled with simplified products that are motivated by product certification?

Is there an argument to be made that it is better to get people to do something (e.g. save for retirement), even if they do not do the theoretically perfect thing and may be slightly overcharged or overtaxed or be underinsured compared to what “full” advice could have delivered? Is foregoing say 50 bps of annual return through a less than optimum plan, but which is more readily available off the shelf and accessible, better that doing nothing because of barriers to getting advice?

Regarding the workplace delivery option, we need to recognise that this will not necessarily reach the new “gig economy” workers and those not in employment such as the self-employed and “work in the home” parents. Are there lessons from history that can be learnt and updated for today’s world? For example, a latter day “man from the Pru” or man from the Co-Op who served the needs of the ordinary working man/woman. The economics are challenging of course, but perhaps the state has a more active role to play. A lot of this group may be familiar with using banking apps on a day-to-day basis; could that be leveraged for incremental protection, savings and/or investment purposes?

At one stage, the idea of “nudging” sensible behaviour was in vogue (Ly et al., Reference Ly, Mazar, Zhao and Soman2013). Can people be nudged into doing something, such as taking out some basic life cover, without the idea that they need a full fact-find and full advice or being fully financially literate? Some basic stakeholder products could fit the bill, i.e. low margin but simple that could be used as a starter for people that can be built on as they go through life. Perhaps using kitemarking and with wider use of default options. Perhaps, this would obviate the need for everyone to be fully “financially literate” before they take action.

The “advice gap” is not the primary focus of our research, but is clearly an important and growing topic in its own right (FT, 2019; OpenMoney, 2019). We would suggest that this topic should be considered further and researched perhaps by another working party.

3.3.4. Fiduciary rule for advisers

Courts will look at the substance of a relationship to determine whether a fiduciary duty exists. For a fiduciary duty to exist, there is usually a legitimate expectation that one party (the fiduciary) will act in another’s interest. Indicators of such an expectation include discretion, power to act and vulnerability (Law Commission, 2014).

US regulators are considering a Fiduciary Rule such that advisors must act in the best interests of their clients, and to put their clients’ interests above their own. Advisors must not conceal any potential conflict of interest, and all fees and commissions must be clearly disclosed (see DoL, 2016 for the original rule that was vacated in the US courts; see SEC, 2019 for the recently published best-interest standard for broker-dealers; and see Forbes, 2019 for a discussion of the fiduciary rule in the US). Furthermore, advisors have an important role in promoting financial awareness and assisting consumers to make better informed decisions about the products that they buy. This helps to address a core consumer protection concern about asymmetries of information between financial services product providers and the public to whom the products are sold (IAIS, 2019).

A fiduciary duty would create the necessary, explicit obligation to avoid conflicts of interest altogether (CFS, 2020). Introducing a stronger fiduciary rule in the UK would act as a best practice by reducing conflicts of interest in the advice process and ensuring that customers are provided with products that perform as the provider has led its customers to expect, through the information, representations and advertising provided by or on behalf of the provider, thereby reducing the incidence of inefficient recommendations to customers (Court of Appeal, 2012; MM, 2018).

3.3.5. Introducing a duty of care on firms

Another approach is to adopt a duty of care through regulationFootnote 2 (as proposed by FSCP) where the FSMA would be amended to include explicitly the expectations of the regulator on the relationship between firms and their customers (FSCP, 2017).

The House of Lords Select Committee on Financial Exclusion supported this proposal, recommending that the FSMA should be amended, in order to introduce a requirement for the FCA to make rules setting out a reasonable duty of care for financial services providers to exercise towards their customers. According to the House of Lords: “Such a duty will promote responsible behaviour on the part of business and support sound financial decision-making by customers” (HoL, 2017).

Following this recommendation, the FCA released a discussion paper to understand whether there is a gap in the regulatory and legal framework, or the way we apply it in practice, that could be addressed by introducing a new duty of care on firms (FCA, 2018b). In the summary of feedback received, the FCA stated that: “Most respondents consider that levels of harm to consumers are high and there needs to be change to better protect them” (FCA, 2019a). Given consumers’ low level of financial literacy and understanding of increasingly complex financial products, the working party fully supports this view.

The FCA have recently identified options most likely to address gaps in consumer protection, including new or revised principles to strengthen and clarify firms’ duties to consumers, including considering a potential private right of action for principles breaches (FCA, 2019a). And more recently, in October 2019, Lord Sharkey introduced a Private Members’ Bill into the House of Lords, which proposed amending the FSMA to require the FCA to make rules for authorised persons to owe a duty of care to consumers in their regulated activities (HoL, 2019). The Bill passed the first reading stage in the House of Lords at the end of October, prior to the dissolution of parliament before the 2019 general election, and was formally reintroduced in the House of Lords in January 2020 to account for the new parliamentary session (HoL, 2020).

4. Principles of Financial Literacy

In this section of the paper, we propose in outline suggestions for some fundamental principles of managing money as a framework for improving financial literacy. This is intended as an initial discussion piece, and we acknowledge that there are challenges to be overcome in agreeing content, presentation and wording. There are dangers in saying too much or too little, being too technical or too patronising, being too mundane or too controversial, and we are conscious that the final item will necessarily be constrained by regulatory compliance issues and consistency with other areas of IFoA principles and practice.

However, in this section, we do believe the profession has much to offer and believe there should be an emphasis on what we see as traditional actuarial strengths of attention to risk and return, certainty and uncertainty and that these principles can be applied beyond the traditional actuarial domain of longer-term financial planning.

The eventual wording of these principles will depend on the audience for which they are intended. This will probably mean different versions for different audiences. In practice, we would recommend that a professional mass communicator in the area of finance, such as a financial journalist, is used to produce a version for non-technical consumers. The eventual aim, we suggest, would be a document that is consumer-friendly, interesting and engaging whilst remaining compliant, reflects the unique contribution that actuaries have to offer in this area and enables the Institute and Faculty of Actuaries to engage with like-minded individuals and organisations sharing a common ambition to improve basic financial literacy.

Fundamental Principles of Managing Money

Summary

Key Message: Actively managing and engaging with our finances will make a huge difference across our lifetime. In essence, each area of our finances needs thought and planning. We need plans for

-

Spending,

-

Emergencies,

-

Borrowing,

-

Savings and Investments, and

-

Getting Advice when necessary.

Plan for Spending

Key Message: Poor money management and lack of control over spending can cause serious problems in our lives regardless of how much money we earn. These problems can quickly build up if they are not dealt with and can lead to spiralling debt and long-term damage to our finances, health and well-being. Budgeting forms the foundational platform for any successful financial plan.

Under this heading, we would envisage an emphasis on the need for budgeting and good habits of shopping around and avoiding impulse spending as a foundation of any financial plan. We would also suggest incorporating reference to budgeting tools and apps like Money Dashboard, Yolt, Emma, Oval Money, Cleo, Bean and Rooster Money (for children).

Plan for Emergencies

Key Message: A major challenge in budgeting successfully is how to cope with unplanned spending or emergencies. Equipment (such as cars or heating systems) can break down; people can lose jobs or get sick or injured; families can unexpectedly grow. Building a financial buffer and taking out appropriate insurance represent the second stage in a basic financial plan.

Under this heading, we would envisage a recognition that there are essentially three ways to plan for emergencies – creating a financial buffer, insurance and borrowing – with some basic analysis of the strengths and weaknesses in each method. We would expect an emphasis on building a financial buffer (rainy day money) and on insuring for major risks to financial well-being and a de-emphasis of convenient but expensive borrowing options such as credit card loans.

Plan for Borrowing

Key Message: Most of us will need to borrow money at some point in our lives, whether it is a mortgage for a house, a loan or flexible borrowing such as credit cards or overdrafts for day-to-day purchases. Options when comparing lenders can be complex and difficult to understand and making the wrong decisions can lead to a huge difference in the actual cost. Any financial plan will need to take into account when it is right to borrow, and on what terms, and when it is best to repay loans.

Under this heading, we would envisage an emphasis on understanding the basics of borrowing, including the conditions, costs and penalties for default. We also believe that the actuarial profession should be able to contribute to discussion of the way interest rates are quantified using APR, which seems to be little understood by many consumers.

Plan for Savings

Key Message: Most people will acquire over their lifetime both short-term savings and long-term savings like a pension. At this point, a financial plan will start to become more complex as investors strive to maximise returns without, necessarily, understanding the risks involved when going beyond a simple cash-based savings account.

We acknowledge that this is a complex area where it may be controversial to go into too much detail beyond a basic endorsement of saving for future needs. Nevertheless, we do envisage that the actuarial profession can make a contribution on basic principles such as understanding risk and return, certainty and uncertainty, which are fundamental to all forms of saving and investment.

Plan for Advice

Key Message: Managing finances can be complex, and there are likely to be times in our lives where specific financial advice is required, or we could benefit from building a long-term relationship with an adviser to support us in all our financial decisions. Nevertheless, the key question is where to go to get reliable and cost-effective advice.

Under this heading, we acknowledge that, although advice is very desirable in a large number of cases, there are major issues about affordability and reliability of advice. Thus, although we might encourage people to take properly regulated advice from sources such as www.societyoflaterlifeadvisers.co.uk, www.unbiased.co.uk, www.findanadviser.org and www.vouchedfor.co.uk, this needs to be balanced against the large numbers who are influenced more by social media, cold calling and recommendations from well-meaning but often poorly informed friends.

5. Implications and Benefits of Our Proposals

In this section, we consider the benefits and limits of our proposals.

5.1. Improving/increasing Financial Literacy at School Level

It would seem to the working party that having school leavers financially literate and able to fend for themselves would be an outcome to be valued. Fewer people falling into debt and failing to be insured and more people choosing financial products more suited to their needs would be valuable improvements in themselves. There is also a benefit in a more confident population.

For financial services companies, surely having more consumers who were buying products that were right for them would be beneficial. A more financially capable population coupled with an attractive and understandable product range might help to reduce the long-lasting problem of underinsurance in the general population.

Yet, it seems to us that, notwithstanding the need and the clear intent to improve financial literacy in schools, this simply is not going to happen easily. We document in section 3 how little progress has been made, despite apparent awareness of the issue.

5.2. Improving Resources Available to Consumers

In the working party’s judgement, having more resources available to help consumers is of marginal benefit. There are many books available, there is plenty on the internet already and today it is a source of disinformation more than we would like. What is needed is less, but more widely known resources, more authoritative and recognised as such.

The benefits of this would be that those who need advice would have it available. It might be that consumers would at the least need an attitude of being prepared to look for advice. It is also the case that they would only search for advice when they were aware that they needed it. The benefit of having good information available is to inform decisions when somebody knows they need to make them.

In any case, we must doubt the ability to make the internet authoritative reliable and truthful, it does not seem to be happening in other areas, so why should it happen in this?

5.3. Special Treatment for Complex Products

In section 3.3.1, we discuss the issue of complex products. There are some rules that have been brought to protect consumers, but nevertheless inappropriate financial products continue to be promoted. We recommend that the FCA makes earlier use of its early intervention powers. It seems in this context germane to mention PPI which has proved a disaster to the banking industry in promoting an insurance product that did not meet customer needs. Earlier intervention would have saved the industry a great deal of money and the FCA a great deal of work. It is worth considering what is the worse for the financial services industry – over eager inhibition of products, or zealous application of hindsight. Prohibition may be a great deal cheaper to industry.

After many sizeable mis-selling scandals, it may need to be accepted that the regulatory regime is too permissive initially and then too harsh to act “in arrears”.

5.4. Introducing Product Certification

Section 3.3.2 discussed introducing a mandatory product certification on all retail financial products. A named actuarial, risk or compliance specialist of sufficient standing should be required to certify that product terms and conditions and marketing information presented to customers is fair, not misleading and should be understandable to the target market.

This product certification should be a principle-based requirement, allowing the named specialist responsible for the certification to substantiate the certification in the appropriate manner. This could be done, for example, via selective market and customer testing based on the target market. Alternatively, certain regulated products such as stakeholder pensions, or products with a kitemark could be certified under a “safe harbour” provision, based on the predefined specifications for such products.

In reality, we may see that only fairly simple products, or those products with suitable predefined configurations, such as default options, would be appropriate for product certification. The market would evolve such that product certification would become synonymous with regulated products and kite certification, and this may spur the development of simplified distribution and advisory mechanisms based on direct sales and robo-advice. Such developments may help mitigate the growing advice gap in the UK market.

We support further research into the concept of a stronger product certification in product development and marketing processes and would suggest that the actuarial profession is ideally placed to contribute to and even take a lead in this research.

5.5. Fiduciary Rule for Advisers

Traditional adviser compensation schemes, such as up-front and trail commissions paid for by the financial-product seller, can introduce acute conflicts of interest in the sales process. Advisers may propose products, features and terms in order to optimise the amount and pattern of commissions received. A fiduciary rule that would legally oblige advisers to act in their clients’ best interests would limit or mitigate such conflicts of interest and should help to ensure that customers are sufficiently informed on the insurance products they are considering buying, before concluding a contract. This may improve the customer satisfaction and value and result in fewer people buying inappropriate or wrong products.

The IDD introduced the general principle that insurance distributors must always act honestly, fairly and professionally in accordance with the best interests of their customers (EU, 2016). The FCA has amended its conduct off business rules to incorporate this principle within its “client’s best interest rule” (FCA, 2019b). The working party supports this general principle.

5.6. Introducing a Duty of Care on Firms

In section 3.3.5, we mention the moves towards bringing a duty of care on firms. The working party supports the introduction of a duty of care on firms because this would embed the concept of fair treatment of, and care to, customers at all levels of a firm’s organisation, including top management. Firms would be required to anticipate customer detriment and give greater emphasis on meeting the needs of customers, all of which would be expected to reduce mis-selling and the need for regulatory intervention.

There are advantages and disadvantages in introducing a duty of care. Some commenters have argued that a legal obligation on firms may discourage innovation and reduce the complexity of products, whilst increasing regulatory burden. We believe that if firms’ cultures were adequately set up to ensure that the duty of care is driven throughout the organisation, this will ultimately lead to a reduction in the amounts of compliance already in existence within firms. Furthermore, the introduction of a duty of care would increase opportunities for firms to innovate and compete without the unnecessary burden currently required by compliance with a number of rules all intended to achieve the single purpose of fair treatment of customers. Given recent comments from politicians and regulators, it does seem that this may happen.

The working party hopes that the ideas presented in this paper will stimulate debate within the actuarial profession and promote firms to take on board a stronger duty of care within their organisations.

6. Conclusions and Recommendations

This section summarises our main conclusions and recommendations.

The working party started off by researching the level of financial literacy in the UK population and internationally, the consequences of poor financial literacy, and thus the need to improve financial literacy. We quickly realised that while improved levels of, and access to, financial education are valuable in itself, it should include delivery mechanisms and content that targets specific audiences, for example vulnerable groups. Vulnerable groups of people are most at risk of making poor financial decisions throughout their lives, which has negative consequences for saving, home ownership, debt levels, retirement and financial inclusion generally. However, the working party supports the view that improving financial literacy is not a silver bullet, but this must be accompanied by additional measures to protect customers in the financial services area if we want to ensure that customers, for example, receive reasonable outcomes from their financial products.

The working party’s research confirmed what we all really know: financial literacy levels are low for most of the population. How should we incorporate this fact into our economic and business steering framework that assumes rational economic actors making decisions in their own best interests? We conclude that, given the low level of financial literacy we have identified, it is clear that this assumption needs to be challenged more and more and that some financial products should not be sold at all.

The issue of complex financial products is a contentious one. Financial innovation can produce new product ideas that meet diverse customer needs. This often comes hand-in-hand with increasing complexity. We do not want to belabour the point, but the working party supports greater use of existing regulatory early-intervention powers to stop the most dangerously complex products being sold to retail customers, and the introduction of a mandatory product certification process that would ensure that products were deemed understandable for the appropriate target market.

One major theme that stands out is that financial firms should be expected to take particular care to ensure that vulnerable consumers are treated fairly as they may be more likely to experience harm (FCA, 2020). Measuring vulnerability is subjective, but the lower the level of financial literacy, and the more complex the financial product, the more vulnerable is the customer. Following on from our initial research into the level of financial literacy, it seems clear to us that a fiduciary duty does exist in principle between advisers and most customers (SCR, 1987; Edelman, Reference Edelman2010). The working party hopes that the EU regulatory requirement that advisers must always act in the best interest of their clients will improve customer protection and ensure their fair treatment.

The working party is also conscious that increased regulation leads to increased costs and thereby may exclude large numbers from receiving cost-effective advice. In consequence, we recommend investigation of a simpler, cheaper regime that can be applied to some simple basic products which are kite-marked as “suitable for all” or suitable for all in a defined socio-economic group.

Finally, the working party researched the concept of introducing a duty of care on financial firms. A duty of care would help a firm to build an organisation that ensures that the firm exercises reasonable care and skill when providing a product or service. This organisational and behavioural change would potentially provide more benefit than a culture of pure regulatory compliance, often manifested through boilerplate disclosure and a tick-box approach to treating customers fairly. A duty of care would help to build trust between a firm and its customers, which would improve the level of trustworthiness in the market.

Poor levels of financial literacy across the general population are a blight on society, an acute concern and require immediate attention and remediation. The working party strongly believes that the IFoA should play a role in the promotion of financial literacy and as a general spokesperson for this topic. We are well placed as a profession to balance the public interest in improving financial literacy with our role as actuarial experts within the financial services industry and wider fields. We note here that as part of the working party’s research, a short survey was conducted during our presentation at the 2018 Life Conference in Liverpool. There was strong support shown for the IFoA having a role in improving financial literacy. To this end, we have prepared five principles of financial literacy that the IFoA should publish on its website in shortened and simplified form. This would then help the profession to engage with like-minded individuals and organisations sharing a common ambition to improve basic financial literacy.Footnote 3

We also recommend that the IFoA should establish a permanent financial literacy panel or member interest group that can act as a supporting voice, sounding board and trusted partner with suitable organisations that are active in this area. The working party believes that the profession has a duty to advocate for improved financial literacy. We hope that the research and ideas presented in this paper will help the profession to take the next step, and we, as a working party, are happy to support with further research, ideas and stimulating material.

Acknowledgements

The working party would like to thank the peer reviewers for their useful comments and suggestions, which have helped to improve the paper. Particular thanks is given to the Life Research Committee for their input and to Peter Towers personally for his detailed feedback on the paper. Helpful comments received from the Life Conference in 2018 are greatly acknowledged.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this publication are those of invited contributors and not necessarily those of their employers or the Institute and Faculty of Actuaries. The Institute and Faculty of Actuaries do not endorse any of the views stated, nor any claims or representations made in this publication and accept no responsibility or liability to any person for loss or damage suffered as a consequence of their placing reliance upon any view, claim or representation made in this publication. The information and expressions of opinion contained in this publication are not intended to be a comprehensive study, nor to provide actuarial advice or advice of any nature and should not be treated as a substitute for specific advice concerning individual situations. On no account may any part of this publication be reproduced without the written permission of the Institute and Faculty of Actuaries.

Appendix 1. Sample websites supporting financial literacy with selected content

Financial Literacy

These sites include content on: what is money; needs and wants; budgeting and specific content relevant for the demographic.

-

1. Financial Literacy for Kids

https://www.investopedia.com/university/teaching-financial-literacy-kids/

-

2. Financial Literacy for Tweens

https://www.investopedia.com/university/teaching-financial-literacy-tweens/

-

3. Financial Literacy for Teens

https://www.investopedia.com/university/teaching-financial-literacy-teens/

-

4. Financial Literacy for Seniors

-

5. General

Vulnerable Consumers

The Money Advice Trust has carried out extensive work in this area and created numerous training materials and resources.

http://www.moneyadvicetrust.org/creditors/creditsector/Pages/Vulnerability-resources-hub.aspx

Advice on Budgeting

https://www.thebalance.com/how-to-make-a-budget-1289587

https://www.moneysavingexpert.com/banking/Budget-planning/ (Martin Lewis)

Planning for Emergencies

1. Insurance

https://www.moneysavingexpert.com/insurance/

https://www.abi.org.uk/data-and-resources/tools-and-resources/how-to-buy-insurance/

2. Emergency savings

This site includes content on: what is an emergency fund; how much should you save – 3 months of your usual income is a good minimum amount to aim for; how to save and other ways to cover unexpected costs.

https://www.money.co.uk/guides/do-you-really-need-an-emergency-fund.htm

Advice on Borrowing and Debt

These sited include content on: what is the best way to borrow; how do credit cards and personal loans work; cutting existing loan costs; representative APR examples and cheap mortgage financing.

https://www.moneyadviceservice.org.uk/en/articles/alternatives-to-payday-loans

https://www.moneysavingexpert.com/borrowing/

https://www.moneysupermarket.com/money-made-easy/what-is-the-best-way-to-borrow/

Advice on Saving and Investment

This is an area where there are countless websites promoting different investment opportunities. However, in line with the rest of this paper, only the basic saving and investment situations will be covered here. The selected websites below include content describing various options, including those with tax advantages.

1. Savings

The next introduces ‘The Savings Fountain’. Think of it like a champagne fountain – put your cash into the best-paying savings vehicle possible, then when that is full and overflowing, fill up the next best, and so on: 1. Lifetime ISAs/Help to Buy ISAs → 2. Bank accounts … → 7. Easy-access savings.

https://www.moneysavingexpert.com/savings/which-saving-account/

2. Investments

The next site introduces ‘The five golden rules of investing’: 1. The greater the return you want, the more risk you will usually have to accept. 2. Do not put all your eggs in one basket. 3. It is recommended you to invest for at least 5 years. 4. If you do not review your portfolio regularly, you could end up with a share account which loses money. 5. Investments can go down as well as up. Do not be tempted to sell or buy shares just because everyone else is.

https://www.moneysavingexpert.com/savings/investment-beginners/

This next site includes a round-up of five key things to remember: 1. Save up an emergency fund of 3- to 6-months’ worth of living costs before you invest. 2. Think about starting small and watching your investment to see how it goes. 3. If you use your ISA allowance to invest, you will protect more of your money from tax. 4. Be prepared not to touch your investment for at least 5 years. 5. Consider taking advice to help decide what is right for you.

https://www.hsbc.co.uk/wealth/articles/beginners-guide-to-investing/

3. Pensions and Retirement

https://www.ageuk.org.uk/information-advice/money-legal/pensions/

https://www.pensionsadvisoryservice.org.uk/

https://www.which.co.uk/money/pensions-and-retirement/starting-to-plan-your-retirement

Getting Advice

https://www.citizensadvice.org.uk/debt-and-money/getting-financial-advice/

https://www.pensionwise.gov.uk/en/financial-advice

https://www.moneysavingexpert.com/savings/best-financial-advisers/

This last site includes useful content on: How do I find a financial adviser? – First things first, speak to family and friends and find out if they have used an independent financial adviser in your local area. Of course, just because they have had a good (or bad) experience with them, it does not mean that you will have the same experience, but it is certainly a good starting point. Failing that, the following websites are a good place to start:

-

VouchedFor* features independent and restricted advisers.

-

Unbiased.co.uk has a network of 27,000 advisers (both independent and restricted advisers).

-

Your Money has a network of 22,000 advisers of all kinds.

-

the Chartered Institute for Securities & Investments (CISI’s) Wayfinder Tool lists certified financial planners professionals and accredited financial planning firms.

A few Citizens Advice Bureaus also have volunteer IFAs as part of the Moneyplan scheme – check with your local bureau if it is taking part.