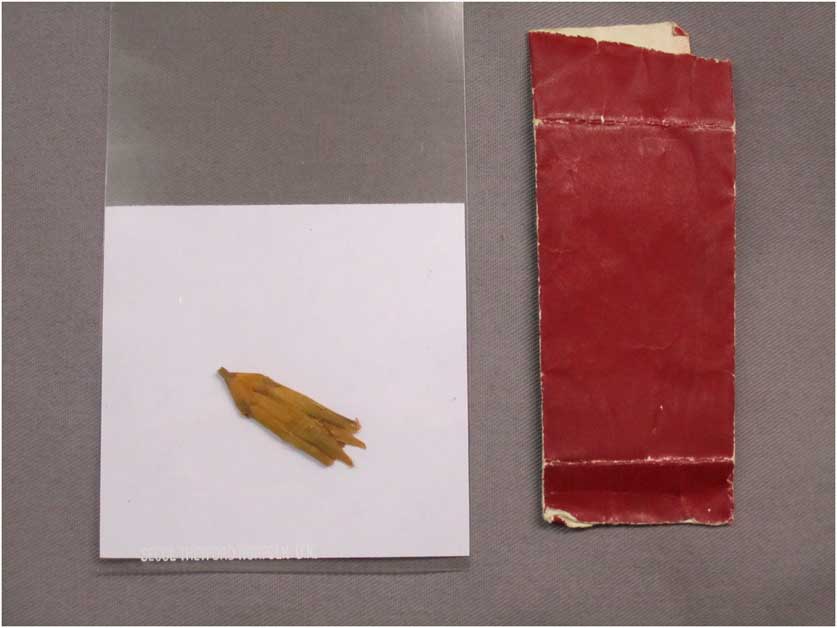

This article arises from an extraordinary archival find: a letter written by an unknown gentleman to his affectionate friend, enclosing a relic of the seminary priest Thomas Maxfield, who was executed at Tyburn on 1 July 1616. Given to the recipient by an eyewitness of his death, the item in question is the calyx of a small pink flower which the martyr had carried with him to the gallows, clinging tightly to it until he expired. The letter, together with accompanying material relating to his life, survives in the Archives of the Catholic Archdiocese of Westminster. Surprisingly, preserved alongside it is a folded piece of red paper with a delicate four-hundred-year-old flower inside (fig. 1).Footnote 1 This poignant token of remembrance, which might so easily have disintegrated into dust in the intervening centuries, provides a tangible link to the elusive past we study.

Figure 1 The calyx of the flower held by Thomas Maxfield as he died, preserved in a red paper package, and kept alongside the letter in which the relic was sent: London, Archives of the Archdiocese of Westminster, AAW, SEC, 16/9/7. By permission of the Archivist of the Archdiocese of Westminster.

A relic may be described as an absent presence. It also fits into the category that Pierre Nora famously called ‘lieux de mémoire’: it is place where ‘memory crystallises and secretes itself’, which ‘stops time and blocks the work of forgetting’.Footnote 2 The capacity of material remains to function as mnemonics and to trigger memory depends on their significance being communicated and interpreted. A mere scrap of flesh or sliver of bone has no independent meaning outside of the cultural context in which it has been identified as the remnant of a person worthy of reverence as a saint or martyr; it remains anonymous until it is named. Its status as a vehicle or peg for memory relies on creating the connection through speech, tradition, ritual, or writing. It derives its authority as a sacred thing from the narratives that become woven around it and from the physical containers in which it is framed, enclosed, and displayed.Footnote 3 And these processes have sensory and emotional as well as cognitive dimensions.Footnote 4

In this instance it is only because the flower is kept with a letter referring directly to it that it is recognised as an object of remembrance. Detached from the text, it might easily be mistaken for another kind of item: a botanical specimen. Like those collected by contemporary naturalists, it was pressed, perhaps between the pages of a missal or primer. Thereby protected from exposure to light and air, it has defied the inevitable fate of so much other organic matter: decay, dissolution, and oblivion. The paper in which the pink is now preserved must accordingly be seen as both a reliquary and a relic itself. Technical distinctions between ‘primary’ and ‘secondary’ relics assume a descending hierarchy of importance and a series of concentric circles demarcating degrees of praesentia that do not reflect the dynamic manner in which memory operates. As Amy G. Remensnyder has commented, if memory represents ‘an attempt to freeze time into a crystalline image’, it simultaneously changes in accordance with it. The significance of hallowed remains and the vessels in which they are kept are continually remade in the light of a community’s ‘imaginative memory’: in turn they become ‘a reflection in the eye of the beholder.’Footnote 5

Taking these insights as its starting point, this article seeks to illuminate the role of relics in the making and metamorphosis of social memory in the English Counter-Reformation world. It uses the case of Thomas Maxfield to explore how the material remnants of a Jacobean martyr functioned as carriers and touchstones of remembrance between the seventeenth- and the twenty-first centuries. It shows how they served to forge links between the adherents of a prohibited faith separated by both space and time. It investigates the role of Maxfield relics in connecting Catholics who remained in Protestant England with the members of the scattered diaspora that developed overseas, and the host societies in which they found asylum, as well as the manner in which they built bridges between and across the generations, between contemporary ear and eye-witnesses of the events that led to Maxfield’s death and those whose knowledge of them was channelled through inherited objects and texts.Footnote 6 At the same time it is attentive to the ways in which this martyr’s multiplying relics and memorials both reflected and fostered tensions within early modern English and European Catholicism. If these fragments paradoxically helped to bind together its disparate elements into a whole, they also served to test its internal coherence and unity and strain its moral and political integrity.Footnote 7

Situating physical remains—body parts and personal possessions—on a continuum with written and printed letters and books, the discussion that follows has a further objective. It endeavours to bring the burgeoning scholarship on Catholic relics into closer dialogue with the growing interest in the Counter Reformation as an historiographical enterprise, as a project to recover the Christian past and to shape the present and future in the image of its primitive purity. Probing the nexus between sacred history and sacred things, it argues that we need to see the collection, preservation, and transmission of hallowed remains as part of a wider attempt to record the history of an embattled minority and to create an archive of its memory for posterity.

The martyrdom of Thomas Maxfield

Thomas Maxfield was the son of a Staffordshire family, also known as Macclesfield. His parents and relatives were stalwart recusants who suffered persecution for their adherence to the old religion and at the time of his birth his mother and father were both in gaol.Footnote 8 Nurtured from his infancy in the Catholic faith, he was sent to Douai College at the age of 13 or 14, where he was educated and then entered the priesthood. He returned to England to labour ‘in our Lord’s vineyard’ in July 1615. He was captured after only three months in the country and imprisoned in the Gatehouse, devoting himself to proselytising fellow inmates. He attempted escape, but was incarcerated in a dungeon and confined in iron shackles, before being transferred to Newgate, where he converted two condemned criminals.Footnote 9

It was Maxfield’s defiant refusal to take the Oath of Allegiance that led to his conviction for treason and sentence of death. His execution for failing to disavow the right of the Pope to excommunicate and depose a heretical monarch and to deny the potential legitimacy of tyrannicide reflected King James I’s determination to make an example of those Catholics who were unwilling to acknowledge his royal authority. However we choose to interpret this controversial device for distinguishing between loyal and disloyal papists, either as a genuine attempt to lay the foundations for coexistence and toleration or as a lethal intrusion into the consciences of religious dissenters, to repudiate it was to court serious trouble.Footnote 10 It is no coincidence that James I reiterated his intransigent hostility towards priests who were unwilling to swear what he regarded as merely civil fealty, engaged in seditious evangelism, and sought to break free of prison at precisely this moment, nor that it occurred in a context in which fissures within the Catholic community about this very issue were both widening and deepening.Footnote 11 Composed in the Clink and condoned by the authorities, the writings of the Benedictine monk Thomas Preston, alias Roger Widdrington, in support of the oath and against the arguments of Robert Bellarmine and Franciscus Suarez, were particularly unsettling here. Giving voice to a constituency of clergy and laity who sought some form of rapprochement with the English state, these aggravated the long running sores opened up by the disputes between seminary priests and Jesuits about ecclesiastical governance and leadership that found expression in the Appellant and Archpriest controversies.Footnote 12 Maxfield’s stance on this issue implicated him directly in the bitter inter- and intraconfessional conflicts that poisoned the religious politics of the era.

It also aligned him closely with the alternative vision for English Catholicism’s future associated with the Society of Jesus and promoted by King Philip III of Spain. Maxfield had close links with the Spanish ambassador Diego de Sarmiento de Acuña, later Count of Gondomar, who personally intervened with James I in the hope of securing a pardon for the priest.Footnote 13 Several of Diego de Sarmiento’s entourage (including his son Don Antonio and his Dominican confessor) came to visit Maxfield in prison, where his tranquillity so impressed them that they fell on their knees and kissed his hands, chains, and the very ground ‘that toucht his sacred footsteps’.Footnote 14 One of his last acts was to ask them to petition Philip III to continue his support for the Douai seminary, from which he had been sent ‘as a mustred soldiar of Christ unto a war’, and in which he expressed intense pride in a farewell letter to a friend, declaring that it had ‘afforded to our poor barren Contrye so much good and happie seed’.Footnote 15 On the night before his execution the ambassador’s family and household held a solemn vigil in his honour. His final journey through the streets towards Tyburn on a hurdle was accompanied, in a provocative act of solidarity, by a guard of honour of English and Spanish gentlemen on horseback. Dressed in a long cassock and biretta, the priest was transported to the place of his martyrdom in a ritual of Protestant humiliation that his supporters transformed into a quasi-liturgical procession akin to a ceremonial act of relic translation. Even before he was dead, Maxfield’s body was regarded as a hallowed object.Footnote 16

Eager to prevent the occasion becoming a public spectacle, the authorities carried out the execution early in the morning. Nevertheless, the crowd that assembled was substantial, according to some reports 4000 strong. In the presence of foreign ambassadors and prominent high ranking Catholics, Maxfield was taunted and challenged to a dispute by the puritan minister Samuel Purchas and given one last chance to take the Oath, which he rebuffed. When the cart was pulled from beneath him, there were those who wished the rope to be cut immediately so that he could be disembowelled before he had breathed his last, but the noblemen present ensured that it was not, crying out that it was ‘barbarous & tyrannical to search with knife & hand the entrals of a live man’.Footnote 17 The virulent anti-Catholicism of other bystanders was vented verbally: one declared triumphantly that his soul had now entered hell. A ‘beardless boy’ who dared to retort ‘Are you the doorkeeper of Hell?’ was thrashed by the man and his accomplices for his impertinence.Footnote 18 The scene was apparently a tumultuous one in which competing passions ran high.

The gallows had been garlanded with flowers and branches and the ground beneath it covered with hay and herbs by well-wishers the previous night, as if, in the words of one observer, it were ‘a bridal chamber or a triumphal chariot’. These were stripped from the gallows by the halberdiers charged with keeping order. As the noose was placed around Maxfield’s neck, the assembled company scrambled to obtain pieces of his clothing and the belongings he threw to the crowd: handkerchiefs, coins, points, gloves, ribbons, and other small gifts.Footnote 19 The desire of onlookers for relics of the imminent martyr reflected what Cardinal William Allen called the ‘godly greedy appetite’ of the laity for holy remains: in many cases people took extreme measures, cutting off the martyrs’ fingers and thumbs and bribing executioners to hand over limbs, organs, and the ropes by which they had been strangled.Footnote 20 On this occasion, the sheriff had explicitly banned people from taking away any remnants of Maxfield’s flesh and blood, together with the straw on which he was quartered, upon pain of imprisonment.Footnote 21 Part of a wider effort to quash an incipient cult, such initiatives should be seen as an extension of earlier Reformation efforts to purge the collections of superstitious relics in cathedrals, churches and shrines, ‘so that no memory of the same remain in walls, glasses, windows or elsewhere’.Footnote 22 Undeterred by these warnings, under cover of darkness, the faithful dug through the night to salvage Maxfield’s head and members from the pit in which he had been buried beneath the putrifying corpses of two criminals, and to ‘carrie them away to be kept with honour & veneration’.Footnote 23

This act of pious archaeology recalls the nocturnal operations to recover the dismembered bodies of priests coordinated by the devout Spanish noblewoman, Luisa de Carvajal, who settled in London near the Spanish embassy. When the remains of a martyr were brought back to her home, she and her companions went out wearing white veils and carrying lighted tapers to conduct them through the passages of the house to her private oratory, where they watched over them until the following morning. She herself then undertook the work of preservation by embalming them in spices and arranged their shipping overseas.Footnote 24 Carvajal, with whom Maxfield seems to have been closely associated, had died two years earlier.Footnote 25 But her work was continued after her death, in this instance, on the direct orders of the ambassador himself, by Captain Diego de Zea y Marino, who oversaw the exhumation of the martyr’s mangled body and placed his remains in a box with lime and vinegar. In 1618 he enshrined the head and bones in a little trunk of crimson velvet, took them to Spain and deposited them in the Franciscan Convent of St Simon of the Island of Redondela. Meanwhile, Maxfield’s right hand found its way to Santiago, where it was kept in the church of St Lorenzo. By 1643, it had acquired a reputation for healing the sick.Footnote 26

Other remains of the martyr seem to have been retained in the safekeeping of Count Gondomar. Together with those of John Almond, executed at Tyburn in December 1612, they were installed in his family chapel in Galicia by his descendants and revered in a domestic cult that eagerly anticipated his beatification.Footnote 27 One or more bones from his arm ended up in the Cathedral at Tuy, where, wrapped in red taffeta, they were kept in the treasury. When the bishop of the diocese visited in 1689, he found that they were labelled ‘St Peter Masphilt’ and ‘St Thomas Masphilt’ respectively. In a muddle that reflects both the difficult circumstances in which the remnants of the English martyrs were obtained and the creative evolution of his cult Thomas Maxfield seems to have acquired an equally illustrious brother. The prelate instructed that the remains he found there should not be exposed to public worship, kissed, placed on the altar, or carried around in procession. Not yet approved and verified by the Apostolic See, they were to be venerated in private until such time as their identity could be ascertained.Footnote 28

The journeys travelled by the vestiges of this ‘martyr on the move’ illustrate the geographical reach of the English Counter Reformation. They highlight the part played by Protestant persecution in feeding the voracious thirst of Catholic Europe for hallowed remains.Footnote 29 They reflect the Council of Trent’s vigorous reassertion of the value of venerating relics in 1563 and the ways in which they came to function as badges of confessional belonging as well as conduits of sacred power.Footnote 30 As recent research has shown, collections such as Philip II’s at the Escorial became symbols of Catholic militancy and a powerful resource for buttressing orthodoxy in the Church’s bastions and heartlands; in territories infected by heresy relics from the newly discovered catacombs in Rome filled the vacuum and gap left by iconoclasm; in Asia and the New World they served as effective missionary tools to convert and instruct indigenous peoples.Footnote 31 Maxfield’s relics were part of a large mobile library of holy objects that reinvigorated the Catholic faith in the age of Counter Reformation. Such forms of ‘portable Christianity’ were critical in facilitating its transformation into a world religion in the course of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries.Footnote 32 But their multiplication and migration also underlines the point that sacred fragments of this kind continued to be surrounded by an aura of ambiguity. They were hedged about by Tridentine regulations designed to prevent misuse of the holy that were the legacy of ongoing anxiety about the embarrassing scandals exposed in the early phases of the Reformation by John Calvin and other Protestant propagandists, who roundly dismissed many hallowed remains as ‘baggage’, ‘merchandise’, ‘rubbish’ and trash’.Footnote 33 In line with tighter controls on canonisation, relics were thus subjected to strict new procedures of authentication.Footnote 34 To complicate the picture further, the spontaneous memory cults that grew up around English martyrs such as Thomas Maxfield beyond the British Isles had dangerous political overtones because the priests in question were convicted traitors. They attest to the vitality of the Counter-Reformation culture of relics even as they underline its capacity to invite controversy and to destabilise diplomatic relations.

Martyrological politics

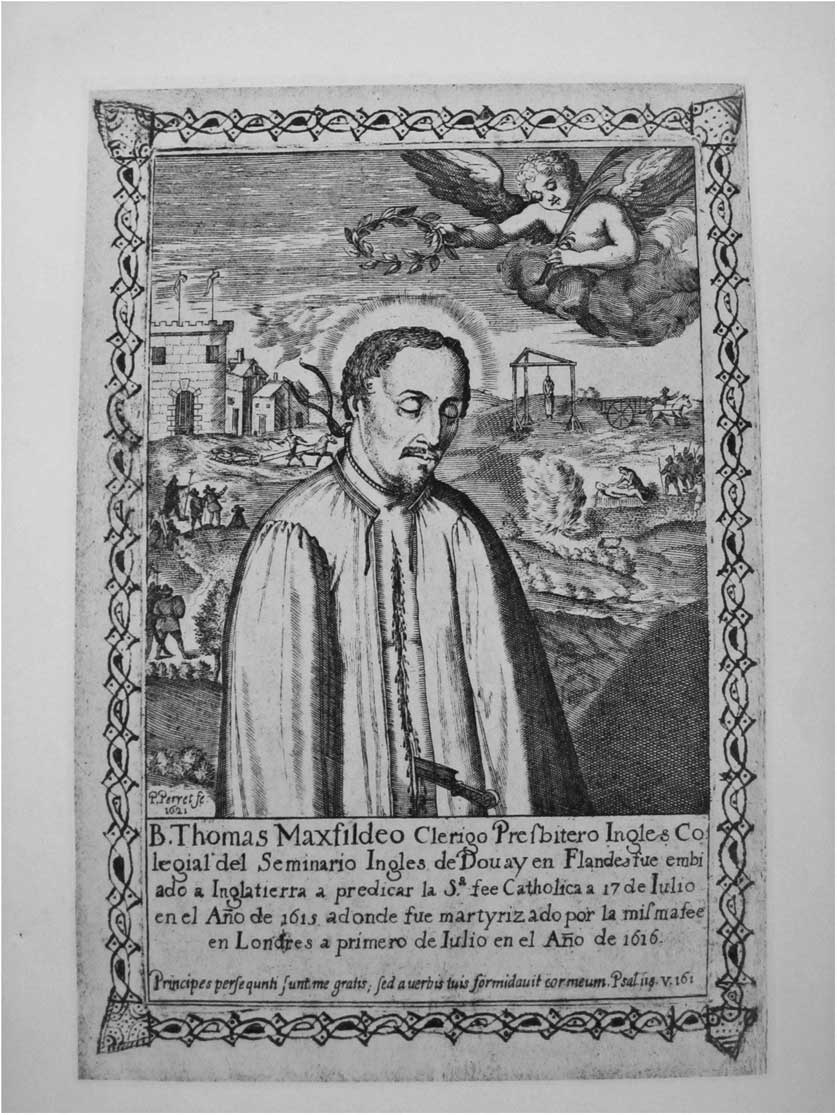

Maxfield’s martyrdom was, therefore, a matter of as much significance to Catholics elsewhere in Christendom as it was to his coreligionists in England. The point is reinforced when we turn to the various accounts of his life and death that began to circulate in Latin and foreign vernaculars soon after his demise in July 1616. One of these, written by a fellow prisoner in Newgate, exists in a fine presentation copy intended for the Spanish ambassador or his chaplain, Diego de la Fuente, in the Biblioteca Nacional, Madrid; other manuscript narratives in Latin can be found in the Westminster Archives and among the Balfour manuscripts in Edinburgh.Footnote 35 A formal, official version was assembled under the direction of Matthew Kellison, President of Douai College. Published later that year, its arrival in England was a source of resentment and tension between James I and Diego de Sarmiento.Footnote 36 This text quickly went through several quarto and duodecimo editions and was translated into Spanish and French.Footnote 37 These books were evidently intended for distribution in the Habsburg Southern Netherlands as well as the Iberian peninsula. In striking contrast, no contemporary version of Thomas Maxfield’s life appears to have been published in his mother tongue. Another index of his evolving cult on the Continent was the sale and dissemination of small engravings showing a cherub bestowing a crown of martyrdom upon his serene but lifeless corpse (fig. 2). These probably derive from the portraits produced by the Catholic painter and servant of the Spanish ambassador to whom his head was lent with precisely this intention in the immediate aftermath of his execution.Footnote 38

Figure 2 Spanish print commemorating the martyrdom of Thomas Maxfield, c. 1621: London, Archives of the Archdiocese of Westminster, AAW, SEC, 16/9/1. By permission of the Archivist of the Archdiocese of Westminster.

What these texts and images also indirectly reflect is the extent to which Maxfield became posthumously embroiled in a struggle between different clerical factions to lay claim to his sanctity. The immediate cause of his death, his refusal to take the Oath of Allegiance, made him a useful piece of ammunition for those determined to uphold the wickedness of swearing it against the arguments of Widdrington and others in favour of doing so. The ‘pestilent books’ set forth by this ‘most unworthy monk’ are referred to directly in the Madrid manuscript, which praises the singular piety of the Spaniards above that of other nations, sharply criticises James I, ‘the only child of that most unhappy Queen of Scots’, and presents itself as ‘an everlasting exposure of that candour and clemency of the English Protestants, of which they boast with great vehemence but little truth’.Footnote 39 Maxfield’s position in this debate likewise opened him up to appropriation by the Society of Jesus, whose efforts to claim certain secular priests as its own martyrs, provoked the understandable irritation of their surviving colleagues. Like John Almond, Robert Drury and Roger Cadwallader, he seems to have been the target of a calculated attempt to reinvent him as a quasi-Jesuit.Footnote 40 It is telling that the first relation of his death to appear in print was a Spanish translation of his Latin vita prepared by Joseph Cresswell for the English College Press at St Omer.Footnote 41 The narratives of Maxfield’s death that circulated must thus be situated against the backdrop of the ideological disputes that were fracturing the Jacobean Catholic community. They were complex manoeuvres in a game of martyrological chess that had both international and domestic dimensions.

These published texts were polemical interventions in several other respects. Conforming to humanist and Tridentine conventions of hagiography, they present Maxfield as an exemplar of heroic virtue and stoical suffering and focus on refuting the official claim that he was guilty of treason and demonstrating that he had died for his religion alone. Accordingly, they are largely free of the traditional miracles associated with compilations such as the Golden Legend which exposed Catholicism to Protestant ridicule and sarcasm. Like the martyrological texts discussed by Anne Dillon, they are ‘meticulous in avoiding the inclusion of any such sensationalist accretions’.Footnote 42 Their register and tone is one of caution and restraint, though they do note that it was reputed a ‘wonder’ or ‘indeed providence of God’ that a thick cloud of mist or fog had concealed the endeavours of the ‘pious thieves’ who rescued the ‘sacred pledges’ of his relics as dawn broke and the rising sun threatened to reveal them.Footnote 43 This was not a nature-defying supernatural sign so much as the Lord working with and through normal elements and forces. By contrast, the manuscript account sent to the Spanish ambassador tells of two visions that confirmed Maxfield’s sanctity to his fellow prisoners. One of these occurred on the night before his condemnation and involved ‘a globe of dazzling light’ that obliged the recipient ‘to hide his eyes beneath the coverlet of the bed’ lest he should be blinded by its radiance.Footnote 44

Miracles of this kind were a potential liability. They laid Catholicism open to fresh allegations of forgery and fraudulence that echoed the rhetorical strategies that Protestant controversialists deployed to discredit relics. They built on a longer tradition of anti-popish literature in which notorious fakes such as the Blood of Hailes and the mechanical Rood of Boxley were made into mnemonics of the egregious imposture and falsehood of popery itself.Footnote 45 And this was a discourse that recent developments had served to reanimate, notably the case of Henry Garnet’s ‘straw’. The exquisite portrait of the Gunpowder Plot martyr’s face, said to have appeared on a blood stained ear of corn obtained from the gallows on which he had been executed, became a cause célèbre in the years after 1606. Attributed by the Jesuit John Gerard to the mighty hand of God, who ‘is able both out of stones and straws to raise a sufficient defence for His faithful servants’,Footnote 46 this prompted much Catholic admiration, but it also unleashed a volley of vicious Protestant polemic alleging that the effigy was either the work of an ingenious miniaturist or an instance of diabolical cunning and guile.Footnote 47 It fuelled a mood of contempt for ‘new popish wonders’ that found expression in the apostate priest Richard Sheldon’s Survey of the Miracles of the Church of Rome. Published in the very year of Maxfield’s death, this text sharply denounced such ‘fopperies’ and ‘fooleries’ as ‘Ignatian lyes’ and demonic devices for seducing the unsuspecting laity. It mocked the tales of prodigies associated with the martyrs that were circulating among his former co-religionists as ‘fabulous narrations’, insisting that stories of ‘the shining face of Frier Buckley, upon London Bridge’, the horse drawing a hurdle that stood still and refused to budge, and the finger and thumb of Edmund Genings that miraculously yielded themselves into the hands of a young virgin were notorious examples of credulity that proved that Catholicism was an Antichristian religion.Footnote 48

It is indicative of how closely these controversies about relics and miracles were entangled with current internecine clerical disputes, that Sheldon’s own defection to Protestantism was linked to his advocacy of the Oath of Allegiance.Footnote 49 The story of Thomas Newton, a Lincolnshire gentleman who claimed to have been visited by the Virgin Mary in Stamford gaol in 1612 and warned against swearing it, is a further case in point. The entire treatise that Sheldon wrote refuting this ‘idle vision’ never made it into print, because the authorities considered him ‘fitter for Bedlam then to have any answere made to his phantastick dreame’. But Widdrington’s denunciation of the apparition as ‘the vehement imagination of a troubled braine’ or ‘a mere illusion of Satan’ was published in his 1613 pamphlet championing the oath.Footnote 50 This was the febrile atmosphere in which Maxfield’s vitae were written and in which his multiple and competing afterlives emerged. It may help to explain why they are largely silent on the subject of the home-grown cult of devotion to his corporeal and contact remains that evolved after his death.

The domestic relic cult of Thomas Maxfield

In contexts such as England where Catholicism was a Church under the cross, relics were highly mobile objects. Ejected from churches and shrines, the principal domain in which they circulated and were used was the private household.Footnote 51 As Robyn Malo has persuasively argued, one of the ironies of the Reformation was to make relics more rather than less accessible to the laity than they had been hitherto and to facilitate more intimate forms of devotion to them.Footnote 52 For laypeople such as Anne Dacre, Countess of Arundel, who wore a relic of Robert Southwell close to her body and concealed in her clothing, physical contact with these hallowed remnants was inextricably linked with the task of recollection.Footnote 53 Other recusants kept sacred objects in their private chambers: among the ‘supersticious reliques’ discovered during a raid on the lodgings of the Catholic sisters Elizabeth and Bridget Brome in 1586 was ‘a little clout wrapped up in paper with a droppe of blood in it’ kept inside a casket.Footnote 54 In the hands of the laity, who were their chief custodians, these sacred things became ideologically and politically charged. In a climate of persecution, possession of hallowed objects was incriminating evidence of adherence to an illicit and prohibited religion.

They nevertheless functioned as highly effective mechanisms for promoting oppositional religious identities, alongside other devotional aids such as agnus dei and rosaries that could easily be concealed within one’s home or clothing.Footnote 55 The miracles associated with the relics of recent martyrs were a powerful resource for missionaries seeking to bolster the morale of wavering Catholics and to convince Protestants that the Church of Rome was the institutional embodiment of the truth on earth. The stories about the wonders they performed that circulated around the recusant underground served as threads that bound together a beleaguered body of believers. Retelling these testimonies of divine approbation, orally and scribally, helped to cement the imagined community of the Catholic faithful. Joint and collaborative creations of the clergy and laity, the texts in which such miracles were recorded, no less than the material objects reputed to have performed them, became objects of devotion and sites of memory.

And it is clear that Thomas Maxfield’s death set these twin processes in motion once more. The movement of his relics was paralleled by the transmission of news about their miraculous effects and properties. John Gee’s scurrilous anti-Catholic tract, The Foot out of the Snare of 1624 allows us to glimpse this through a hostile lens: in it he mercilessly mocked the rumour that a crucifix adorned with some of Maxfield’s relics, which was stolen from its clerical owner and transported fifty miles, had mysteriously returned of its own accord.Footnote 56 A recognisable variant of medieval exempla about divine intervention to punish and reverse an act of furta sacra, the story offers insight into how quickly Maxfield had been assimilated into enduring traditions of vernacular hagiography that were not interrupted by the Reformation.Footnote 57 Like the remains of many of his fellow martyrs, Maxfield’s own rapidly became the focus of veneration by clergy and laypeople who were unprepared to wait for the slow and increasingly stringent procedures by which holy people were officially made into saints.

Maxfield himself evidently shared a deep belief in the power of the relics of executed priests to perform miracles. A surviving letter celebrates the role of the Staffordshire priest Robert Sutton in exorcising a man possessed by the devil, ‘a wonderfull worke here latly effected by the great power and goodnesse of god’, and by the merits and mediation of the executed missionary. The relics in question were Sutton’s forefinger and thumb, the survival of which was regarded as supernatural itself: it was said that these hallowed digits, with which he had consecrated the host, had remained intact when the rest of his quartered limbs had been picked clean by birds. Maxfield professed to have been an eyewitness of the exorcism and promised to send ‘a fuller notice and intelligence’.Footnote 58 His reverence for Sutton and his relics had an intensely personal dimension: Sutton had been arrested and executed in 1587, after visiting Maxfield’s own father, William, in gaol. And it was for harbouring Sutton and other missionaries that William Maxfield himself had been sentenced to death.Footnote 59

After Thomas’s execution in 1616, this letter, together with other correspondence he had sent in connection with his mission and during his imprisonment, were preserved.Footnote 60 We must see them as forms of what Ulinka Rublack has called grapho-relics.Footnote 61 They may be compared with the tiny slip of paper bearing the signature of another Jacobean martyr, George Napper, surviving among the Bede Camm papers at Downside,Footnote 62 and with the autographs of Ignatius Loyola that reputedly performed miracles of healing in Spain and parts of its empire in the seventeenth century.Footnote 63 They are also akin to the small packages, no longer extant, which John Gerard sent from his prison cell to friends, containing rosaries he had crafted out of pieces of orange peel strung together on silk thread.Footnote 64 Containers for the sacred, they became precious mementoes of the martyrs themselves.

The prominence of such textual relics in early modern English Catholic devotion was in large part a consequence of the determined efforts of the authorities to prevent the collection of their corporeal remains. While, as we have seen, this stopped neither the acquisition nor circulation of the latter, it did serve to invest other items with which they had come into contact with particular significance. If, by the late Middle Ages, ‘writing often filled the gap created by the material occlusion’ of relics in enclosed reliquaries,Footnote 65 after the Reformation it remained a partial substitute for bodily interaction with them. The mundane belongings that martyrs such as Maxfield threw to the crowd and gave to their disciples likewise became conduits of emotion and devotion that brought the laity into the close proximity with the divine for which they so earnestly craved.

It is in this context that the preservation of so ephemeral an item as a flower must be assessed. It seems probable that the pink that Maxfield carried with him to his death was plucked from the garland that surrounded the gallows at Tyburn. According to Gerard’s Herball (1597) this sweet-smelling plant grew freely in the gardens and outlying fields of London in this period and was popularly esteemed for use in posies and nosegays.Footnote 66 It also spoke a language and was freighted with symbolic value. Long linked with the remembrance of deceased loved ones, pinks or carnations have a specifically Christian connotation: according to legend, they first appeared on earth when Jesus carried the cross, springing up where the tears of his weeping mother, the Virgin Mary fell. They are flowers that recall the Crucifixion, which Maxfield’s own sacrificial death evoked and mimicked.Footnote 67 The ultimate act of imitatio Christi, early modern martyrdom was a rite of remembrance itself.Footnote 68

The letter in which the flower relic was enclosed reveals that it was given to the writer by a nobleman, who in turn had obtained it from some eyewitnesses of the execution (fig. 3). The names of the sender and other persons have been scrawled out, together with an entire sentence, underlining the subversive nature of the trade in illicit relics and the degree to which transmitting precious cargo of this kind by post was a perilous exercise.Footnote 69 Together with writings by and about the deceased priest, the pressed flower and the letter by which it was conveyed were monumenta martyrum, monuments of the martyr. Fingering, feeling and handling these contact relics played a key part in transmitting the memory of Maxfield. Roman Catholicism had always been a religious culture in which mnemonic practices involving the senses were critical, including the recitation of prayer with the aid of elaborately carved rosary beads and balls that opened to reveal the Nativity and Crucifixion.Footnote 70 And it remained so after the advent of Protestantism. Touching objects that the martyrs had themselves touched forged a powerful link between the living and the holy dead.Footnote 71

Figure 3 A paper reliquary: the letter in which Maxfield’s flower relic was enclosed, censored to avoid incriminating the individuals named. London, Archives of the Archdiocese of Westminster, AAW, SEC, 16/9/7. By permission of the Archivist of the Archdiocese of Westminster.

In turn, the act of copying and transcribing the Latin and vernacular vitae of the post-Reformation martyrs was a mode of remembering. In a community deprived of shrines and sarcophagi and robbed of the bodies of many of its dismembered martyrs, manuscripts and texts performed the function of tombs.Footnote 72 Arthur Marotti has commented that during the Renaissance ‘reverence for relics migrated into print culture, where the remains of a person were verbal’.Footnote 73 The tendency for paper to become a form of both relic and reliquary was pronounced in an environment in which books often served as surrogates for priests, operating in the guise of what the Spanish Dominican Luis de Granada termed ‘dumb preachers’.Footnote 74 Further complicating the stereotype of Protestantism as a religion of the word and Catholicism as a religion of habitual action and ritual, this suggests that Catholics were implicated in, rather than marginal to, the process by which the words ‘relic’ and ‘remain’ were subtly redefined to encompass texts themselves. On both sides of the confessional divide, they were increasingly used to describe posthumously published or scribally dispersed writings as well as corporeal remnants.Footnote 75 Catholics conceived of the bodies of their martyrs as books and vice versa. In 1581 Edmund Campion explicitly compared ‘our books written with ink’ with those ‘daily being published, written in blood’, while in his Epistle of comfort, Robert Southwell defiantly told Protestants: ‘our deade quarters and bones confound youre heresy’.Footnote 76 Maxfield’s relics and writings were dual weapons in the struggle to expel heresy and reverse the Reformation, revive the religious past that it had cast into oblivion, and reconnect England with the faith that it had professed continuously for so many centuries.

Migrations and mutations

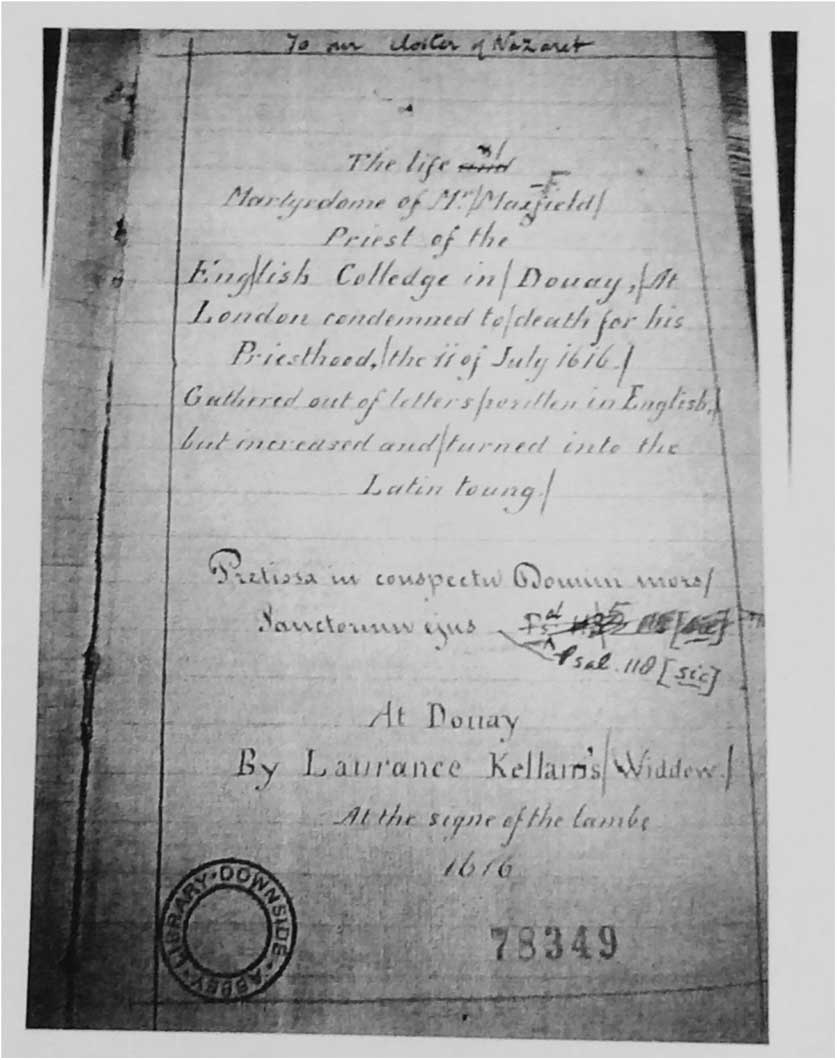

Vital elements of the mission at home, both material and textual relics also played a critical part in connecting those who stayed in England with a floating body of individuals who went into self-imposed exile overseas, supporting the Catholic cause from the religious houses in which they resided on the continent. This was the setting in which the next of Maxfield’s afterlives emerged. This is a vernacular translation of the Latin narrative of Maxfield’s death prepared by John Bolt, chaplain, and organist at St Monica’s Augustinian convent at Louvain. He did so at the request of Frances Stanford, who was related to the martyr, and who became prioress of the order’s newly established daughter house in Bruges in 1629.Footnote 77 Referring to her as Maxfield’s ‘holy cosen’, in the dedicatory epistle Bolt said that the cost of printing had dissuaded him from publishing it, though the format of the title page of the manuscript implies that it was intended for the press. Nevertheless, he ‘thought it best for [the text] to be written with myne owne hand, that so your Reverence might remember it, & in remembering it, might be mindfull to pray for the wrighter, as he will not cease to pray for you’.Footnote 78 The sentiment was widely shared: script was thought to be a more intimate medium for memory-work than print. Bolt’s text cemented the link between Frances Stanford and her heroic relative and it may have been she who wrote the words ‘To our closter of Nazareth’ on the first page.Footnote 79 Perhaps she later gave it as a gift to the community of nuns of which she was a member, together with the copy of the Spanish engraving of the martyr. In turn, these items became in some sense relics of the abbess herself. In a manner akin to the ‘holy radioactivity’ that emanated from sacred things,Footnote 80 her own kinship with Maxfield brought her into the orbit of his sanctity. Such familial links were often the source of hallowed remnants that helped to bind expatriate religious around a shared history of persecution and a common heritage of affliction. They created a web of connections that strengthened the tendency to see the cloistered religious as martyrs and indeed as living relics themselves.Footnote 81

Like the Latin text, Bolt’s translation incorporates a transcription of Maxfield’s last fragmentary letter to his mother and siblings. In this he implored them ‘by the bowels of love & perfect Charitie’ to lead lives commensurate with the salvation of their souls and to recollect the example of their own father, ‘who suffering frequent persecutions for faith & justice did also at last undergoe with a chearful & courageous minde the most uniust sentence of death ….’.Footnote 82 He called upon them to engage in an act of pious remembrance and his own martyrdom may be seen as a form of filial devotion and mimicry. The sentence tails off in a way that implies that William Macclesfield or Maxfield had himself paid the ultimate price for his faith—in fact he was reprieved from capital punishment and died in prison of natural causes. But the text as transcribed suggests otherwise to the reader: consciously or unconsciously it rewrites history and twists memory. It integrates Frances Stanford into a spiritual and biological pedigree that claimed not one but two martyrs as members. It invites its reader to intercede for the souls of her ancestors, just as they would for hers through their reciprocal prayers. It is a letter that embodies a Catholic economy of mutual, salvific remembering that breached the divide between the generations in this world and the next.

Like the Madrid manuscript vita, which was emblazoned with the arms of both the martyr and his mother’s family,Footnote 83 the life that Bolt translated and transcribed conveyed Maxfield’s own consciousness of being part of a devout dynasty: the son of parents who were themselves constant confessors. This was intertwined with a desire to align his own endeavours and sufferings with those of the evangelists who had originally planted the Catholic faith in these islands—he spoke of his own family and the ancient family of the faith in the same breath. On the scaffold, he declared that he followed in the footsteps of St Augustine and his company, who in ‘tymes-past … first of all brought the light of the true faith into this kingdome of Saxons, being wrapt within the darknesse of Idolatrie’.Footnote 84 In the weeks leading to his death, when his spirit quailed, he had been encouraged to embrace his fate patiently and willingly by a godly woman who visited him and ‘willed him to thinck on the victories of the Martyrs, & imitate the constant faith of them whose tryumphs & rewards he coveted’. This may be the same unidentified lady of ‘singular pietie & bouldnesse’ who cried out loudly after he expired ‘Gloria in Excelsis Deo: for the Conversion of England; for the Conversion of England’ and declared that the blood of the martyrs would rebuild the broken stones of the Church. Maxfield and those who witnessed his demise integrated this event into a chain of continuity stretching back to primitive times.Footnote 85

We must see the collection, preservation and dissemination of his corporeal and textual relics, no less than the hagiographical narratives that circulated about him, as dimensions of the thriving contemporary impulse delineated for us by Simon Ditchfield and other scholars—the vigorous resurgence of interest in writing and compiling sacred histories.Footnote 86 Like these texts, relics helped to link early modern Catholics with a heroic past and their transmission as precious heirlooms to later generations was itself part of the plan for securing a future in which Rome would be restored to its rightful dominance. It was a means of combatting the human instinct to forget and a way of keeping alive the memory of events that would inspire one’s descendants, friends and colleagues to fight for the faith in which they had been born and baptised or which they had voluntarily embraced as converts.

This is illustrated by the case of Antonio de Castro, a ‘very curious & devout’ Spanish youth who was a scholar at the English College in St Omer and kept ‘a little Cabbinet of many Reliques of our English martyrs’. The boy was a relative of the Count of Gondomar, who had bestowed upon his father a relic of John Almond, which was one of the sacred remnants enshrined in this casket, which passed into the custody of John Wilson after Antonio’s death in 1622. In turn, Wilson sent a small piece of Almond to Matthew Kellison, President of Douai College.Footnote 87 A tantalizing question arises: might this chest have also contained Maxfield’s flower and the letter that became its reliquary?

There is, then, a distinct sense in which the Counter Reformation, and the circumstances of persecution in which English Catholics found themselves, served to intensify the status of relics as conveyers of memory and as lieux de mémoire. To remember early modern martyrs with and through their material and textual remains was one of the arts of resistance to Protestant domination. The itineraries of these physical traces help to illuminate how an expatriate community dispersed across the Continent overcame the challenges of dislocation, imagined itself a unified whole, and used its past to map out a plan for the restoration of England to its historic allegiance to Rome in the future.Footnote 88

Transformation and proliferation

The movements of Maxfield’s manuscript lives, letters, and relics in the eighteenth century are obscure, but his memory was revitalised by the work of Richard Challoner and Charles Dodd. He appears in the former’s Memoirs of Missionary Priests (1741-2) and in the latter’s Church History, conceived and written as antidote to Gilbert Burnet’s whig Protestant version of the Reformation past which appeared in Latin and English beginning in 1681.Footnote 89 Proclaiming their impartiality and denying that they were works of apology, both publications reveal the interconnections between scholarship and spirituality. They support recent work by Jan Machielsen and Dmitri Levitin on the blurred boundaries between erudition and devotion in this period.Footnote 90 Our tendency to situate them in opposition reflects the secularising narratives about the development of our discipline of which we are heirs. Although Challoner and Dodd were reliant on the seventeenth-century texts already discussed, their accounts of Maxfield’s life reflect certain shifts in emphasis and priority. In Dodd’s text, it is not the authorities but the ‘mob’ who bury his mangled quarters in a hole to prevent superstitious papists from collecting his relics. He leaves to ‘the reader’s speculation’ whether the poor light that prevented the discovery of those who excavated his body from the pit was ‘merely accidental, or a smile from Heaven’.Footnote 91 These modifications are indicative of a society that was becoming more preoccupied with ‘civility’ and civilised conduct, in which the literate elite were overtly distancing themselves from the behaviour and experience of the ‘vulgar’, and in which attitudes towards the miraculous and providential were evolving in accordance with wider alterations in intellectual culture in the spheres of natural philosophy, theology, and epistemology. They are also an index of the subtle ways in which Charles Dodd reshaped traditional recusant history. Seeking to foster rational dialogue between receptive Anglicans and moderate men of his own religion, and decidedly Gallican, cosmopolitan and irenic in tone, his text was an artefact of the wider Catholic Enlightenment.Footnote 92 Rewritten in alignment with the preoccupations of a new age, these new versions of Maxfield’s martyrdom attest to the ongoing transformation of his memory and the continuing proliferation of his afterlives.

This organic process can also be observed in the various places to which his corporeal and textual remains had migrated since 1616. Traditions about the relics of Maxfield and other martyrs mutated in creative and revealing ways. At Tuy Cathedral, as we have seen, Maxfield was made into two distinct martyrs, related by blood; here, to cement the identification of his bones, a copy of the narrative informatio became wrapped around them. This duplication was closely entangled with the idea that the Maxfield relics were stored in a chest together with those of a certain ‘St Abondio’, identified with the Roman martyr St Abundius, whose head had been brought to the cathedral from Rome. It was supposed that the remains of the same martyrs were preserved in the chapel of St Anne at Gondomar. By the late nineteenth century, these were locally known as those of Tomás and Abondio, who were commonly spoken of as two Spanish priests who had been martyred in England. Maxfield had been domesticated and naturalised by the society in which he found asylum after his death. His mysterious companion ‘St Abondio’ was probably John Almond, the name being a curious corruption of the Spanish word ‘Amondio’, perhaps as a result of its transmission by word of mouth.Footnote 93 In a further example of wishful thinking and pious theft, the account of his ‘Spanish Pilgrimage’ that Dom Gilbert Dolan published after he journeyed to Gondomar in 1885 identified the relics of these two martyrs with those of Richard Scott and the Benedictine missionary Maurus Scott, the latter being a member of Dolan’s own order. He brought the small fragments that were graciously bestowed upon him to Downside Abbey, determined ‘to deposit my spoils in the safe keeping of Alma Mater’. Under an assumed name, part of Maxfield’s body was thus repatriated.Footnote 94 Another bone, the radius at Tuy, was obtained by his colleague Bede Camm and presented to the Benedictine Convent at Tyburn, in commemoration of the place of his martyrdom.Footnote 95 The restless movement of Maxfield’s relics and the multiple alter egos and mistaken identities that bedevil our understanding of his evolving cult simultaneously testify to its persisting vitality.

The same is true of the later travels and transmutations of his literary lives. Bolt’s presentation copy of his translation of Maxfield’s Latin vita remained in the Augustinian convent at Bruges until the late nineteenth century. In 1882, the mother superior of the convent gave it to the Jesuit John Morris in order to assist the cause for the beatification of the English martyrs, which he played a critical part in championing. It was subsequently absorbed into the Postulator’s Library at the Jesuit house in Mount Street, London, where it was encountered by John Hungerford Pollen, the indefatigable early twentieth-century scholar of English Catholicism. Pollen transcribed and edited it, together with Maxfield’s surviving letters—some of which were then kept in the Archives of the Archdiocese of Westminster and some in St Edmund’s College, Ware—for the Catholic Record Society in 1906.Footnote 96 In 1924, Pollen produced a new edition of Challoner’s Memoirs, in which Maxfield once again appeared. Combining scholarship and piety, his work in publishing the records of the heroic days of English Catholic persecution perpetuated the enduring tradition of recusant history even as it self-consciously sought to set it on a more academic footing.Footnote 97 The equally industrious attempts of the ‘monastic martyrologist’ Bede Camm to recover material related to the English martyrs and their ‘forbidden shrines’—and indeed to record and unravel the convoluted history of Thomas Maxfield and his physical remains—must be seen in the same light.Footnote 98 And by referring to the ‘pathetic’ remnant reverently enclosed in a letter, both Pollen and Camm helped ensure that the delicate calyx of a pink flower continued to be identified and remembered as a relic of the Jacobean martyr.Footnote 99

Their work reminds us that the lines we conventionally draw between devotion and antiquarianism are unhelpful and anachronistic. The texts they composed and edited must themselves be recognised as powerful vessels and touchstones of memory and prayer. The act of reading them fostered a reverence that was reactivated when Maxfield and over hundred other Tudor and Stuart priests were formally beatified in 1929, giving official sanction to an international cult that had flourished since the second decade of the seventeenth century: the reader of my own second-hand copy of Pollen’s Challoner has inserted ‘Blessed’ in front of their names.

It is fortunate that Pollen took the trouble to put Bolt’s life of Maxfield into print because it cannot now be located. It seems to have disappeared from the archives in Mount Street. Nor is it at Downside Abbey, where about half of Maxfield’s bodily relics now reside. The item in its catalogue with this title is not in fact Bolt’s copy, but Pollen’s transcription prepared for the typesetter, laid out as closely as possible to resemble the original (fig. 4).Footnote 100

Figure 4 J. H. Pollen’s transcription of the title-page of the ‘The life and martyrdome of Mr Maxfield Preist 1616’: Stratton-on-the-Fosse, Downside Abbey, MS F72C. By permission of the Downside Abbey Trustees. © Downside Abbey Trustees.

This scribal facsimile serves as a surrogate link in the chain of memory. It coexists in Downside’s library with Bede Camm’s papers on the English martyrs, which contain later transcriptions of Maxfield’s Latin lives. Here record keeping is a species of relic collecting, just as relic collecting has always been a form of remembrance. The archives and libraries in which Maxfield’s epistolary relics and the flower are currently kept have become their reliquaries in the same way as the sacred physical containers that enclose holy remains are themselves archives of memory.

These repositories enshrine and instantiate a rival historical tradition that developed as a riposte to the anti-Catholic Protestant metanarratives embodied in the major national libraries upon which we still so uncritically rely. As Jennifer Summit has shown in her penetrating book, Memory’s Library, the medieval manuscripts that form the core of the British, Bodleian and Parker Libraries reflect the values of their compilers. Selected, annotated and censored in accordance with these preoccupations, consciously and unconsciously they reinforce the intertwined stories of a hidden remnant of true believers who resisted the corrupt papacy during the dark ages and of the swift onset and triumph of the Reformation.Footnote 101 As Liesbeth Corens has shown, the collections energetically assembled by Catholic priests such as Ralph Weldon and Christopher Greene in the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries must be seen as a series of efforts to create a set of counter archives.Footnote 102 This was a strategy consciously continued by their Victorian and Edwardian successors, the Jesuits Henry Foley and J. H. Pollen and the Benedictine Bede Camm, and it was also a major motivating impulse behind the foundation of the Catholic Record Society in 1904. The editorial efforts of such scholars to preserve the memory of the victims of the Elizabethan and Stuart persecutions have provided modern historians with a rich reservoir of primary source material from which to construct the history of English Catholicism, but they have also shaped it in ways that efface the intra-clerical conflicts and lay frictions that divided this geographically dispersed community in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. Obscuring the tense domestic and international politics of the Counter-Reformation martyrs, miracles, and relics in a minority context, they have encouraged us to remember certain aspects of Thomas Maxfield’s cult at the expense of others. They have served to homogenise the many competing versions of his life and death that swirled around England and Europe in the wake of his execution in 1616.

In conclusion, this article has delineated the parallel roles of objects and texts, transcription and collection, writing and relics in the creation and transmission of memory in the post-Reformation Catholic community. It has shown how sacred fragments of the martyrs served to bind an embattled minority with their coreligionists overseas, as well as to link the living and the dead. They helped early modern members of the Church of Rome to comprehend their sufferings by connecting them with those of early Christian missionaries and to use them to nurture the faith of subsequent generations. The case of Thomas Maxfield also illustrates the mutability of memory and the part played by material as well as textual culture in its formation and evolution. The migration of his relics across space and time, from the gallows to the convent, abbey, and library, and from the seventeenth century to the twenty-first, is an emblem of its complex and multidimensional quality in the wake of the profound cultural rupture wrought by the English Reformations. And these were movements that turned on attempts to control remembering and to engender forms of amnesia and forgetting.

One consequence of these developments may have been to enhance the status of relics as conduits of memory as well as devotion and sacred energy. This hypothesis sits uneasily beside Daniel Woolf’s claim in The Social Circulation of the Past that the official abolition of relic worship helped to nurture an interest in antiquity and that the antiquarian artefact filled the empty space left by the holocaust of hallowed remains that accompanied the religious changes of the 1530s, 40s, and 50s.Footnote 103 Predicated on a Weberian model of disenchantment, this implies a polarity between timeless sacred objects and temporally located historic ones, and between recollection and veneration, which the foregoing discussion has served to question and unsettle. For early modern Catholics, relics were important mnemonic devices. The reliquaries in which they were enclosed were simultaneously archives in the same way as archives were also shrines. Hallowed remains operated alongside martyrologies and sacred histories as mechanisms for establishing the legitimacy and authenticity of their religion, for demonstrating its material and institutional continuity from antiquity to the present, and for keeping alive hope for a glorious future. Touching the holy became increasingly inseparable from seeing the past. It did so because the terrain of history was the chief battleground on which the confessional wars sparked by the Reformation were waged.