Introduction

In 1671, on the island of Java, a prince by the name of Trunajaya (d. 1680) waged a rebellion.Footnote 1 This rebellion was not against the Dutch, as some might expect, but against the powerful Javanese kingdom of Mataram. The 1670s were to be a portentous decade for the people of Java. According to the Javanese calendar, the end of the sixteenth century was near and events of that time were seen as omens of what was to come: crops were failing, people were starving, lunar and solar eclipses darkened the sky, and the eruption of Mount Merapi, the great volcano in the island's heartland, showered the Javanese kingdom with its silver-grey ashes. The king of Mataram, Susuhunan Amangkurat I, sought the help of the Dutch to combat Trunajaya's rebellion. To this, the governor general of the Dutch East India Company (Vereenigde Oostindische Compagnie – VOC), Joan Maatsuijcker, reluctantly agreed, appointing a battle-tested admiral named Cornelius Speelman as commander. In the fateful year of 1677 – the Javanese year of 1600 – Amangkurat I fled as rebels stormed his palace, and died, leaving his young son Amangkurat II to rule over the once mighty kingdom. As the rebellion raged across the coast and countryside, this new king decided to seek the blessings of an important Muslim saint in the mountains of Giri. Believing that Amangkurat II was not the rightful heir to the throne but a bastard child of the Dutch commander, Speelman, the Muslim saint ultimately refused to give his blessings to the young king.Footnote 2 Instead, he forged an alliance with Trunajaya, joining the ‘great war’ that reverberated across the island. In April 1680, this saint, known as the Panembahan of Giri, waged a ‘furious’ battle – what one Javanese source called a ‘holy war’ – against the allied forces of the Javanese and the Dutch.Footnote 3

In 1670 on the island of Ambon, located roughly 1,200 miles east of Java (Figure 1), Georg Everhard Rumphius (1627–1702) was said to be going blind. Rumphius had long been a prominent member of the Council of Ambon, undertaking both administrative and natural investigations crucial to VOC commercial operations in the eastern archipelago.Footnote 4 The very first VOC headquarters in the East Indies were, in fact, not the famed Batavian settlement on the northwest coast of Java, but a battered fort on the clove-filled island of Ambon. The Dutch had wrested the fortification from the Portuguese in 1606, and it was in Ambon in 1610 that the VOC created its first post of governor general to oversee their global trade in valuable spices.Footnote 5 By the time Rumphius arrived on the island as a young company soldier in 1653, the geographies of power had shifted westwards and it was Batavia that had become the heart of VOC overseas operations, which stretched from the Cape of Good Hope in Africa to the man-made island of Deshima in Japan. While Rumphius began his career as an ordinary soldier, he quickly climbed the local administrative ranks of the company: by 1657 he was listed as an ‘under merchant’ and ‘head’ of two important provinces on the island, and five years later he was promoted to the position of ‘merchant’.Footnote 6 But now, in 1670, letters began to circulate among a small circle of administrators regarding his impaired vision, immobility and doubtful standing within the local council.Footnote 7 For Rumphius, too, the 1670s proved to be a time of devastation and loss. In 1674, the earth shook, toppling roofs, collapsing walls and sinking two chunks of the island into the ocean; included among the countless deaths were Rumphius's wife, his two children and a ‘maid’.Footnote 8 He lived out the rest of his forty-nine years on that tiny island, working on several natural-historical projects best exemplified in two of his now well-known works, Het Amboinsch Kruydboek (The Ambonese Herbarium) and D'Amboinsche Rariteitkamer (The Ambonese Curiosity Chamber).

Figure 1. A map of the Indonesian archipelago, in M.C. Ricklefs, History of Modern Indonesia since c.1200, Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, p. 471.

Among his descriptions of shellfish and crayfish, of cockles and shells, minerals and soils, there is in the third volume of Rumphius's Rariteitkamer a strange account of a ‘false holy man’ who on 25 April 1680 waged battle against VOC forces in the mountains of Giri. In this chapter, titled ‘Rare iron in the Indies’, Rumphius revelled in the failure of ‘certain iron rings and bracelets’ that the men of Giri wore as protective amulets in war. These iron accoutrements were described as ‘superstitions’ and ‘Moorish trickeries’ propagated by the ‘holy man’ of Giri who had spread ‘false miracles’ among the people of Java.Footnote 9 This holy man was in fact the Panembahan of Giri, who had accused the young king Amangkurat II of being the bastard son of a Dutch infidel and had forthwith joined Trunajaya in the rebellion. It is striking to read this history of war, recounted, albeit briefly, in Rumphius's Rariteikamer, a work that was purportedly written for ‘the eyes of Enthusiasts’ to demonstrate the ‘strangeness of Nature’ unknown to European audiences of the time.Footnote 10 Why did Rumphius care to include this episode in his Rariteitkamer? How did Rumphius, living 1,200 miles away from the north coast of Java, learn about the Muslim saint, his iron amulets and his defeat in battle? In short, how did Rumphius know what he knew without having travelled to the island himself?

This article attempts to answer these questions by tracing the inter-island information networks of one man, whose world was much larger than the tiny island of Ambon itself. While the titles of Rumphius's best-known works prominently bear the name of the island he called home, his writings are rich in detail about other islands in the vast archipelago that straddled the maritime regions of the Indian and Pacific Oceans.Footnote 11 The ubiquity of connections – a constant in past and present accounts about the movement of people, ideas and things across these maritime spaces – can obscure how such activities were experienced and interpreted by those who did not or could not venture beyond the shores of their native or adopted homelands.Footnote 12 Rumphius's life and works hold a unique place in this scheme. A travelling soldier turned administrator and naturalist, he never left Ambon once struck by debilitating blindness. Yet, from his adopted island home, he became a mediator of mediators, acquiring and ultimately demonstrating his knowledge of objects, people and places near and far through a combination of his cross-cultural, administrative and commercial networks across the archipelago. Long-lasting proximity bred exceptional familiarity. However, Rumphius – born in Wölfersheim (present-day Germany), working for a Dutch trading company, communicating in Dutch, Malay and German – was nevertheless a stranger among strangers at home, navigating multiple hierarchies of power that permeated the VOC's Asian empire, as well as continental Europe. Although not expressly hired as a company physician, a position typically reserved for university-trained scholars, he followed the practices of European naturalists who had visited the Indies: he collected and translated local knowledge into both curious and profitable information intended for European, or more specifically Dutch-language, readership.Footnote 13

In Rumphius's case, these practices took place on a tiny island that he placed at the centre of a diverse archipelagic world. This positional and narrative recentring on the part of the naturalist who never left adds a slightly different contour to the localized trajectories of both imperial and indigenous knowledge. Recently, historians of science have sharpened their gaze on local processes of knowledge making in imperial settings – variously described as ‘appropriative’, ‘collaborative’, ‘entangled’, ‘hybrid’ – foregrounding mechanisms that fed developments of scientific knowledge in European centres. These studies have paid closer attention to a multiplicity of figures on the ground and their complex negotiations, in a growing recognition of non-European agency. By looking closely at these cross-cultural engagements, they have highlighted the global nature of knowledge making, from its production to its mobilization, in the early modern world.Footnote 14 Like other naturalists, Rumphius ultimately set his sights on Europe, but he did so standing ‘at the end of an inverted telescope’, on an island far removed from the imperial centres of Europe, the company and the archipelago.Footnote 15 Tracing his inter-island information networks from this perspective brings to light different types of local imperial and indigenous actors, as well as illustrating how information was subject to multiple lines of mediation, through oral retellings, translations and scribal summations from different islands. As Sujit Sivasundaram reminds us, it would indeed be ‘simplistic to posit … that one culture collected and the other was collected’.Footnote 16 As this article shows, a wide range of local actors participated in the collection, mediation and circulation of information and objects, especially in the context of commerce and war. Behind Rumphius's projections of an Amboinsche world, then, his writings demonstrate how ‘local’ knowledge produced on one island was the product of criss-crossing inter-island information networks that were both indigenous and imperial, cumulative and selective, as information underwent its own complicated processes of transmission and transformation within the archipelago before it ever reached its intended audience in Europe.

This article is organized into four concentric parts, each providing an ever wider net of contexts for understanding the inter-island networks of one man, who remains at the heart of this piece. Exploring Rumphius's networks has involved not only the tracing of specific information and the different actors involved, but a reassessment of how he perceived and projected multiple boundaries of difference in one of the world's largest archipelagos. The first part of this article considers how Rumphius may have understood his experiences of cross-cultural interactions in Ambon by examining his meticulous recording of plant names in a local language. The next part assesses how he was able to learn about plants – and their medical, military and experimental uses – from both named and unnamed Muslim intermediaries, some of whom were itinerant merchants from far-flung islands, while others were elite members of the island's provinces. I continue to tease out the nature of Rumphius's inter-island networks in the last half of this article by focusing on his role as a mediator for one area of information in particular: the circulation of ring-shaped ornaments and the stories told about them. The third part demonstrates how he used his administrative, commercial and household networks to participate in an already existing indigenous trade of rings and bracelets stretching across the whole length of the archipelago. Here, Rumphius's narratives represent a case where a naturalist's interpretation of an object as a curiosity relied almost entirely on oral retellings about its powers of invulnerability. Rumphius, I highlight, was not simply a collector or transmitter of information; he was a mediator among other mediators negotiating several economies of exchange. Finally, the last part of this article returns to the episode of the iron rings of Giri and attempts to answer how Rumphius knew about the Panembahan's amulets while living 1,200 miles away from the imperial centres of Java. By untangling this one entwined narrative of wonders and wars piece by piece, this last section explores how Rumphius integrated or omitted different kinds of mediated information culled from his inter-island information networks. This, I suggest, resulted in a selective narrative that was intended to render the iron amulets uniquely appealing as curiosities to his intended European audiences.

What's in a name

Since Mary Louise Pratt's influential study of the contact zone, scholars have explored the dialectics of power in imperial spaces, where clearly defined European and non-European cultures were believed to ‘meet, clash, and grapple with each other’.Footnote 17 In Rumphius's case, defining those cultural boundaries is a much more delicate task. This is in part because Rumphius's life story and questions about his identity complicate assumed divisions between the ‘European’ and the ‘indigenous’ on the one hand, and the ‘imperial’ and the ‘local’ on the other. Unlike university-trained naturalists who travelled to the Indies only to return home to build a career upon their overseas experiences, Rumphius arrived in Ambon as a young soldier of twenty-five and lived there as a VOC administrator until his death. His household consisted of a local wife, who was of mixed Portuguese and indigenous descent, mixed children and slaves from other islands in the archipelago.Footnote 18 The question of the naturalist's self-identification within the hierarchies of the VOC is also far from straightforward. He could neither wholly assimilate into indigenous cultures nor could he be called a ‘proper’ Dutchman.Footnote 19 Rumphius sometimes referred to himself and his readers as ‘us Europeans’ or to ‘our nation’, at least in writing. These perplexing expressions of desire for solidarity nevertheless intimated a consciousness of multiple lines of difference between himself, other Europeans and the indigenous populations. How did his German roots shape his identity and how did his family life affect the way he understood the people and cultures around him? In short, how did his experiences in Ambon influence his perceptions of difference?

Engaging in cross-cultural interactions in the Indies did not necessarily mean that the naturalist was living in a cosmopolitan social world, where identities were fluid or less relevant to the social, political and economic constraints that structured imperial endeavours. As Francesca Trivellato reminds us, if making connections meant a crossing of boundaries, then those boundaries, too, had to be marked and more clearly defined.Footnote 20 But perhaps precisely for this reason, and as Natalie Rothman has compellingly argued, it is crucial to focus on who exactly was marking and defining those boundaries in the processes of cultural mediation.Footnote 21 Given Rumphius's own experiences in Ambon, his works could be read to gauge the force of individual perception in negotiating multiple boundaries. While there are no definitive answers to the question of his self-identification, I suggest that one may glean his perceptions and projections of difference by looking at the way he detailed the names of plants. Here, we start with a plant that Rumphius considered ‘one of the most beautiful, graceful, as well as the most valuable of all of my known plants’: ‘Caryophyllum: Garioffel-nagelen: Tsjencke’.Footnote 22 Or, as it is better known today, the clove plant.

Rumphius began by mentioning the Latin word for the clove plant – Caryophyllum – as listed in Book 1, Chapter 16 of Carolus Clusius's Exoticorum Libri Decem and traced this ‘contemporary Greek and Latin’ to Pliny and Paulus Aegineta, citing their books and chapters in turn.Footnote 23 Rumphius associated caryophyllon with Arabic, writing that ‘without a doubt’ caryophyllon was derived from the ‘old Arabic’ karumpsel. This resembled the words the ‘Persians, Arabs and Turks’ used for cloves, calafur and caraful, as stated in Garcia de Orta's Aromatum.Footnote 24 After bringing up the Italian, Dutch, German and Portuguese names for the plant, Rumphius turned to Malay, the lingua franca of the archipelago and a language he had long been exposed to.Footnote 25 What is striking about Rumphius's use of Malay is his meticulous recording of the range of the language's subtle variations. He noted that in ‘contemporary Malay’ the clove plant was referred to as tsjancke and tsjencke, which may have originated from the Chinese word for the same plant, thenghio. But in ‘old Malay’, he noted, cloves were called bugulawan and bongulawan. While these old Malay terms for cloves did not survive among the Malays themselves, variations of it appeared among the Ambonese and their neighbouring Ternatens, who called the plant buhulawan and boholawa respectively.Footnote 26 Traditionally, scholars have traced categorizations of the Malay language to François Valentyn's descriptions of ‘high’ and ‘low’ Malay; that is, Malay used in royal and religious settings, and Malay used in bazaars. Rumphius's distinction between ‘old’ and ‘contemporary’ Malay in the seventeenth century, however, has escaped scholarly attention.Footnote 27 His awareness seems to intimate that he was interested in the historical development of the language: he did not perceive it as static, but as changing over time through influences from other languages and dialects.

This example illustrates that Rumphius showed enough interest to note the plant's name in the various pronunciations of Malay used among different indigenous populations in the eastern archipelago. Certainly, this careful attention to the nuances and variations in the naming of the clove plant may have proved advantageous to European merchants engaged in commercial activities in the archipelago.Footnote 28 Partaking in the clove trade from one island, after all, would have nurtured a familiarity with local variations used by different island populations engaged in inter-island commerce. However, such textual displays of subtle phonetic difference – which would have been meaningless to the untrained ears of a university physician and inefficient for the European merchant speaking in the ‘low’ bazaar variant of the lingua franca – suggest the extent to which Rumphius's experiences in Ambon influenced the scales of similarity and difference he brought to bear on his understanding of local variation. For it mattered to Rumphius that various island populations pronounced the Malay word for the clove plant differently, allowing him to highlight the importance of its local confluences and divergences over time, even if it was just in name.Footnote 29 This example also suggests that Rumphius most likely met individuals from different parts of the eastern archipelago and noticed differences as slight as a missing or added syllable in their pronunciations. He thought it worthwhile to highlight that the clove plant was pronounced as both tsjancke and tsjencke, both bugulawan and bongulawan, and both buhulawan and boholawa. While he did not acknowledge his intermediaries in this case, one cannot help but wonder how else he could have known these minute phonetic details without having listened to individuals pronounce the words aloud. He perceived multiple boundaries of difference and yet intimated that they were different only by degree. For, even as he laid out these subtle variations, Rumphius emphasized their semantic affinity: bugulawan, bongulawan, buhulawan, and boholawa all referred to the same, decipherable, ubiquitous clove plant.

Intermediaries named and unnamed

In 1675, Rumphius noted, something exceptional happened: Javanese merchants were suddenly buying cloves from the Moluccas in great quantities. Rumphius used this opportunity to find out how and for what purpose the Javanese, among others, were using the clove plant. For, he wrote, while it was common knowledge that cloves had been ‘in great use’ by ‘the Chinese, Balinese, Javanese and Malays’ since times of old, Europeans did not know exactly why they were willing to pay such a high price for them. What was it about the clove plant that impelled local merchants from other islands to come to Ambon? On this exceptional occasion, he stated, ‘some [of them] have given us, in a roundabout way, a certain opening’.Footnote 30 Although Rumphius did not mention these particular intermediaries by name, this was one way of letting his readers know that he had discussed the matter with local merchants, who had come to Ambon plying the complex inter-island sea routes that connected the island to other islands in the archipelago. In other words, Rumphius did not have to travel to increase his knowledge of plants: it was his local intermediaries who were itinerant.Footnote 31

The overlapping realms of the Moluccan trading ‘zones’ were teeming with local merchants, who had long engaged in inter-island exchange of goods and products for the survival of local island polities. These complex ‘zones’ encompassed the islands of Halmahera, Ternate and Tidore in the north; Ambon, Seram and Buru in the centre; and Banda, the Aru-Kei islands and New Guinea in the south (Figure 1).Footnote 32 While the entrance of European powers significantly altered the dynamics of trade and power in the region, these newcomers continued to be reliant on local trading populations from islands within the Moluccas and beyond, such as Java and Makassar.Footnote 33 For Ambon specifically, the VOC's monopolization of the clove plant rendered the island a significant port of trade, attracting local merchants of various ethnic groups from all over the archipelago.Footnote 34 Rumphius, it seems, reaped the benefits of living on a speck of land that had decades prior served as the centre of the VOC's political, military and economic operation in the East Indies.

What did he learn from his itinerant intermediaries? Firstly, he noted that cloves were believed to induce something called ‘Crat Sala’ or ‘Liat Sala’ (literally ‘false vision’), which rendered one invisible and, therefore, invulnerable to ‘enemy fire’. This was a ‘devilish and superstitious art’ used at times for ‘thievery and forbidding situations’, he wrote. Yet, after further inquiry, this seemed to make sense: his intermediaries maintained that they were seeking the plant because in the year of 1675 there raged ‘such a great war’ on the island of Java.Footnote 35 This was undoubtedly a reference to Trunajaya's rebellion against the Javanese kingdom of Mataram, a war that engulfed almost the whole of Java from 1671 to 1680. The belief that it would render them invulnerable to enemy attacks explained the unusual spike in the Javanese demand for cloves in 1675. One wonders whether Rumphius made the previous remarks with a certain sense of irony. Although he believed these tales of invulnerability to be mere superstition, he also knew that the VOC was the main supplier of the physical matter that made it plausible.Footnote 36 Indeed, here we witness not only a direct correlation between local beliefs and local markets but also its mutual entanglement with the VOC's commercial interests. Moreover, this episode demonstrates how the information economy on one island depended on inter-island commercial networks that existed within the archipelago: Rumphius learned about local plants precisely because the VOC supplied the island's visitors with the raw substance about which Rumphius sought more information.

Rumphius seldom acknowledged the help he received from local intermediaries. However, when he did, he did not hesitate to express praise for their expertise in the knowledge of plants.Footnote 37 The following three examples show that some of Rumphius's named intermediaries were identified as Muslims or ‘Moors’ and held positions of leadership within their local communities. The fact that Rumphius worked with men of high status, particularly in the 1660s, is not surprising: working as a full-time VOC administrator in northern Ambon, Rumphius would have had direct access to high-ranking local figures in the region's provinces. However, their status alone neither engendered complete trust nor rendered their authority unequivocal.Footnote 38 If the goal of praising the status of his intermediaries was to heighten the credibility of the information provided, why did Rumphius not acknowledge them more frequently and systematically? While social status may account for how Rumphius gained access to local knowledge, it does not adequately explain why he decided to name and at times un-name them. As the next three examples demonstrate, Rumphius's emphasis was on his perception of the intermediaries’ specific experiences with and expertise in the knowledge of plants. Although it is apparent that such experiences were tied to their social status, Rumphius at times indicated that status alone did not immediately lend authority to the information given.

In the third volume of his Kruydboek, Rumphius wrote about a tree that had long remained unknown to his countrymen, one that was believed to hold vices in the sap, which would make men go blind. While the wood of this tree resembled a variant of the famous agalwood, he referred to the tree in Latin as ‘Arbor excacans’ (sic) and in Malay as kaju mata buta, which means literally ‘the wood of blind eyes’.Footnote 39 This tree was known to be as ‘ugly’ as it was dangerous. Its ‘gnarled’ and ‘knotty’ branches hung over the main trunk of the tree, draping it from its spiky tips to its marshy roots, so that in order to get close to it, people had to crawl on all fours and risk the effects of its dangerous fumes.Footnote 40 Rumphius first encountered this tree in the mid-1660s when he was stationed at Hila, an experience that – he admits – had initially been painful and difficult. In recounting how he learned of this plant, readers are introduced to one of his local intermediaries: ‘Pattj Cuhu’, a ‘Moor from Hitoe’:

In the same year [1665] I was shown this wood for the first time by Pattj Cuhu, a Regent or Orang Kaya from the Hituese village of Elj, an experienced person in the knowledge of plants who has given me much assistance in this work, which is why I also thought it appropriate to lay his remembrance here.Footnote 41

This short passage reveals fragments of Patih Cuhu's own identity, while also providing insights into the kind the relationship Rumphius was able to foster with a local man from Ambon. The title patih suggests that he was a high-ranking official and the designation orang kaya indicates that he was a nobleman. VOC administrators commonly referred to orang kaya in their reports for their assistance in gathering population data for the island's different provinces.Footnote 42 Patih Cuhu was, in other words, one of the elite members of his society and would have had regular contact with VOC administrators. Such administrative connections were valuable not only for matters of governance and commerce, but also for natural investigations, pointing to the overlap between scientific, commercial and administrative concerns for the VOC and local elites. While Rumphius noted that Patih Cuhu was the first to alert him to the existence of this plant and provided him with ‘much assistance’, he does not detail what kind of information Patih Cuhu personally imparted. By ‘lay[ing] his remembrance’ in the body of the text, Rumphius was giving credit to Patih Cuhu on paper, citing him by name, title and place of origin. Here, it seems that Rumphius's intention was simply to bestow attribution on a man who had helped him and perhaps to do so by identifying him to the fullest extent possible. For, like many in the archipelago, Patih Cuhu seems to have had only one personal name: without his title, his name would have simply been Cuhu.

Patih Cuhu was not the only person who helped Rumphius gain knowledge of ‘the wood of blind eyes’. Towards the end of the chapter, he mentioned another man by the name of Iman Reti. Again, the title ‘iman’ (imam) is tied to status, with Rumphius stating that he was a ‘Muslim priest from [the neighbouring island of] Buru’. Remarkably, Rumphius referred to him as his ‘boss’, who had taught him how to distil oil from the same wood.Footnote 43 Based on these lessons, Rumphius wrote that to extract ‘a thick, sticky oil, in the form of turpentine’, one had to follow a series of steps. Namely, one should soak small pieces of the wood in seawater before placing them in a ventilated earthen pot with two saucers partially covering its top and bottom. Once the pieces of wood were ignited, a fatty residue would begin to melt and separate into oil. After half an hour of heating, the oil would be ‘thick, blackish and sticky’, ‘as viscous as turpentine’, radiating a ‘smoke from the scent, which it never loses’.Footnote 44 Most importantly, Rumphius recounted his errors of judgement when he tried to perform this distillation himself:

I wanted to moisten the wood without water in the repeat [of the distillation], on account of the smell of the smoke that came from it, but my Boss, who taught me this distillation, Iman Reti, a Muslim priest from Buru, urged me, that such [seawater] was necessary because otherwise, the wood would touch the fire and no oil would be given.Footnote 45

Iman Reti was correcting Rumphius on the proper method of and the necessary ingredients for carrying out the distillation successfully. Here it is the local Muslim cleric who becomes the authority figure, a teacher who instructs and indeed corrects the European naturalist. Rumphius's acknowledgement of Iman Reti's expertise seems to be based not only on the latter's knowledge of plants, but also on the perception that he discriminated between matters of fact and error based on experimental practice: how else could Iman Reti have known that the lack of seawater would have resulted in a failed distillation?

Rumphius often relied on the testimonies of his intermediaries, even if these were based on local beliefs he described as ‘superstitions’. In Book 10 of his Kruydboek, he mentions Abdul Rackman, a ‘former regent of Hila’, who had told him of a ‘fateful experiment’ he had seen performed on one of his friends.Footnote 46 This involved mixing two kinds of the prunella or ‘Aijlounija’ herb – the red and the white – which were well known among the Ambonese for having the power to cure ‘superstitious sicknesses’. Such sicknesses included ‘all kinds of magic or harm from evil beings’, glossed in Malay as swangi or pelissit.Footnote 47 According to a legend, a snake carrying the herb in its mouth came across a wounded snake in the woods. The snake chewed up the herb and spat it onto the wounded snake, which, suddenly cured, slithered away from the man who witnessed the scene. People learned of this, Rumphius wrote, and believed that chewing a mixture of the red and white herb and applying the masticated pulp to the skin would not only protect one from ‘visible and invisible ghosts’ but also heal ‘fresh wounds’ of the flesh.Footnote 48 Abdul Rackman had witnessed the latter in an ‘experiment’, Rumphius claimed, when his friend who was suffering from a crocodile bite was healed with the same mixture.

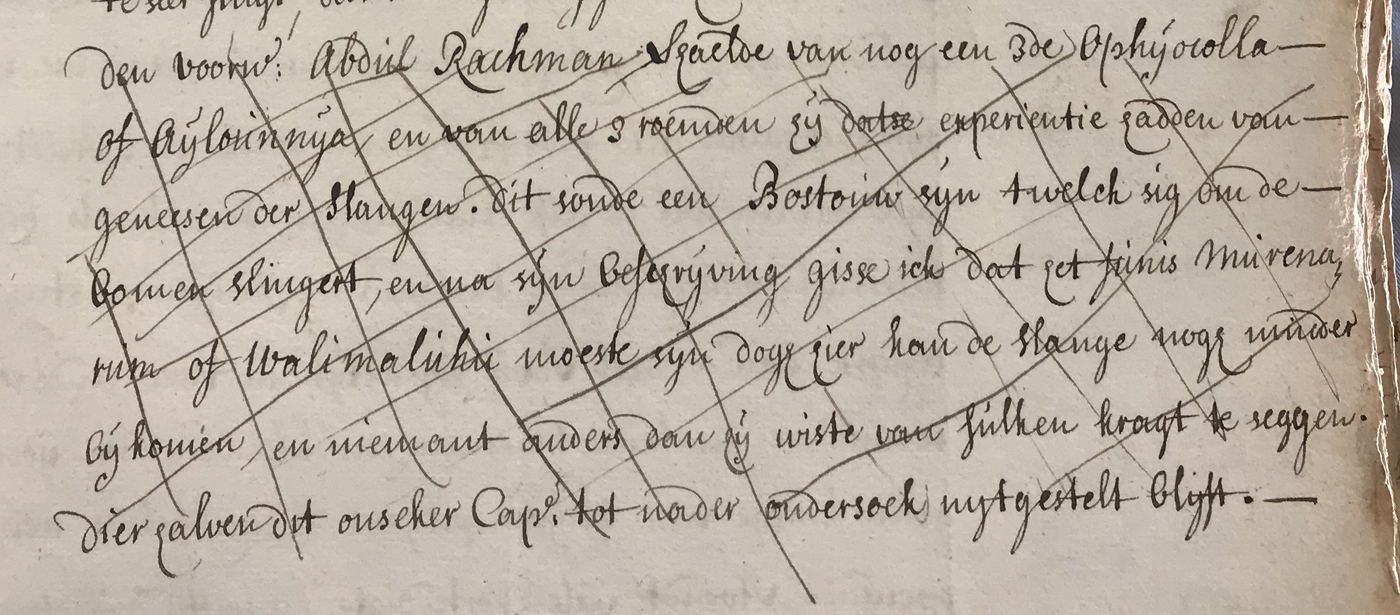

While Rumphius relied on the testimonies of his local intermediaries, he at times doubted their individual authority. When the same Abdul Rackman described another kind of prunella that had ‘experience’ as a ‘remedy of snakes’, Rumphius ‘guessed’ that based on Rackman's descriptions, the plant could only be identified as the ‘funis murenarum or wali Maluku’, which he described in the seventh book of the Kruydboek. However, Rumphius reasoned, it was unlikely that a snake would ever be found near a ‘funis murenarum’ and the information regarding the plant's powers could not be verified by anyone else.Footnote 49 Here, we see that Rumphius fully accepted Rackman's tale about the herb as a ‘remedy of snakes’ but used that information to reason against the certainty of Rackman's testimony. Seeing the need for ‘more detailed research’ and verification, this second mention of Abdul Rackman's assistance was crossed out in the original manuscript (Figure 2). Consequently, this passage was not copied into the other manuscript version of the Kruydboek and does not appear in subsequent translations of the work into Latin or English.Footnote 50 This disappearance of the second mention of Abdul Rackman should alert us to the many differences between the two manuscript copies of the Kruydboek, as well as to the cumulative, open-ended and uncertain nature of information gathering.

Figure 2. The second mention of Abdul Rackman's name and contributions are crossed out in the BPL 314 version of the Kruydboek (Book 10, Chapter 23). This does not appear in BPL 311 or in printed versions of the work in Dutch, Latin or English. Leiden University Library Special Collections, BPL 314, G.E. Rumphius, Het Amboinsch Kruydboek, Book 10, f. 32r.

While distrust was not explicitly mentioned, these examples demonstrate how the thorny issues of trust, credibility and authority were solved neither by the textual presence of indigeneity nor by the mere mention of the intermediary's social status. As the first example shows, Rumphius's mention of Patih Cuhu's social status had more to do with giving proper credit or offering ‘remembrance’ rather than lending credibility to specific descriptions. While Rumphius noted his intermediaries’ status, as the second example shows, Rumphius's trust in Iman Reti was more specifically based on his perception of the imam's discrimination between different ways of knowing. As the last example demonstrates, information from the same high-ranking intermediary was subject to different treatment. Significantly, belief in legends and tales did not disqualify his intermediary as a trustworthy source. In fact, these tales became a part of Rumphius's modus operandi.

Archipelago rings

Tales of magical objects reached Rumphius from islands near and far. ‘Out of the air, through the branches of the trees in the wilderness, he heard something fall’, Rumphius wrote, as if he could imagine the scene of the object's discovery through his intermediaries’ storytelling.Footnote 51 This local storyteller, simply described as ‘a Moor from the village of Mosappel’, was a purveyor of magic rings that local people wore as armlets or bracelets (armringen).Footnote 52 With these ornaments in his possession, the man had travelled to the province of Hila in 1668 to visit Rumphius, who – according to François Valentyn – lived there ‘like a Prince, and with greater repose than many a king’.Footnote 53 He sold Rumphius two magic bracelets of black stone: heirlooms that ‘no longer brought good fortune to his family’ but befitted a man of power like his uncle, who upon discovering the object was convinced that ‘a Djing or Daemon’ had endowed it with its blessings. ‘He has always worn it on the hand as he rode out to war’,Footnote 54 the man told Rumphius, and ‘one neither knew [if] he has ever been wounded nor if he has ever let a drop of blood’. Of course, Rumphius never witnessed the magical workings of these objects himself. ‘They would have no power [in Rumphius's possession], like all such curiosities are said to do’, the unnamed storyteller is said to have assured him, because he ‘did not find it himself or receive it as a gift but purchased it with money’.Footnote 55

Tales of faith and invulnerability, of wars and wonders, often accompanied commercial transactions of rings of power: objects that the local populations actively traded all over the archipelago. In his search for natural wonders, Rumphius – not just as a self-made naturalist but also as a VOC administrator – benefited greatly from the convenient marriage of governance and commerce in the practices of the VOC and of local island polities. Through his administrative, commercial and household networks, Rumphius acquired knowledge of ring-shaped ornaments of different kinds – about their craft, trade and tales of talismanic prowess – and repeatedly described them in his Rariteitkamer, Kruydboek and personal correspondence. Rumphius drew on local beliefs to highlight the value of these objects as curiosities, items that were cherished and displayed among early modern European collectors of nature.Footnote 56 In his discussion of bracelets called mamacur, for instance, Rumphius wrote that they were ‘thick’ and ‘plump’, made of something that looked like glass or a mix of ‘clear stones’ (Figure 3). Holding it up to the light, Rumphius continued, some saw in its transparency floating ‘clouds’ that would change into shapes of snakes and dragons.Footnote 57 They functioned like miniature crystal balls. ‘When [men] would go out to war’, Rumphius claimed, ‘they peered into [these rings] and would foresee therein good or bad fortune’.Footnote 58

Figure 3. Printed image of bracelets (armringen) called mamacur. Leiden University Library Special Collections, 6812/A1, G.E. Rumphius, D'Amboinsche Rariteitkamer, T'Amsterdam: Gedrukt by Francois Halma, 1705.

Other mysteries surrounded their craft: ‘The natives insisted upon us in great earnest that these were not made [by hand] but were from natural stones, emerging from the mountain or the sea’. Such tales of natural manifestation, Rumphius argued, were a demonstration of ‘the renowned salesmanship among these natives’. For these beliefs determined the object's price: one ‘can receive a slave for the worst [quality], but for those so beautifully watered and clouded, one can receive 5, 10, or more slaves’.Footnote 59 Indeed, it was not just naturalists in Europe who were interested in buying what were considered rarities of nature; an active indigenous trade in these objects existed within the archipelago, one that was sharply defined by class differences. ‘The common man may not possess them, at least not openly’, a man from the neighbouring island of Ceram (present-day Seram) told Rumphius, but he ‘must be a great Radja’ or, at least, a man of property and wealth. Indeed, rajas and sultans went to war for them: as did Raja Saulau, ‘the most powerful among the Alphoreezen’, when he waged war against Ceram. An indigenous captain by the name of Hoelong, who oversaw some of these military campaigns, informed Rumphius that ‘such a Ring was worth a hundred slaves, yes, the value of a whole country’. These objects were likewise bought and gifted to kings, with the Javanese ‘cornering the market on green rings’, which were then brought to their monarch as a ‘great gift’.Footnote 60

What others purchased with slaves, Rumphius purchased with ryksdollars.Footnote 61 According to his Makassarese and Malay intermediaries, the one that Rumphius acquired had been brought to Ceram from Aceh in Sumatra, an island at the western end of the archipelago. It was ‘black in appearance’, said Rumphius, ‘but as one held it up to the light, half translucent and dark blue, there swirled yellow and brown specks with gold, of which the most intense glow came from the enamel’. Of these, he continued, ‘the average counted for 7 Ryksdollars, while the good 15 or 16; if it was entirely blue with brown-blue or purple clouds, it was named Dittir Radja, for which they gave 16 to 20 slaves’.Footnote 62 Measured in both ryksdollars and slaves, the trade in these rings was not exclusive to the indigenous nobility: Rumphius, in his capacity as a VOC administrator, participated in an already existing, indigenous network of commerce that connected the various islands of the archipelago. Rumphius was indeed a mediator among mediators as he negotiated multiple economies of exchange. Converting slaves into ryksdollars, he communicated their worth in the language of global finance.Footnote 63 By the same token, as a mediator between the commercial and discursive economies in which these objects ‘travelled’, Rumphius made their local significance essential for their interpretive value as a curiosity.Footnote 64 Through these conversions, these regal and supernatural objects acquired added layers of meaning.

Unlike other natural goods, these items circulated as ready-made products, after raw resources had been extracted from ores and the rings forged in fire by local smiths. The mysteries surrounding their origin and craft, however, prompted Rumphius to inquire into the nature and the tales of the metals used in their production. In particular, he was interested in local weapons that were said to derive their powers from nature: instruments made out of stones that had been struck by bolts of lightning.Footnote 65 Rumphius named these weapons donder-schopjes (literally ‘thunder-spades’) in his Rariteitkamer and told his readers that he had learned about them from the people of Makassar and Celebes (present-day Sulawesi), who were particularly renowned for their ‘art of war’.Footnote 66 Rumphius procured one of these weapons himself, not without ‘great cajoling and good payment’, when a royal ambassador of Tambocco (present-day Bungku) arrived in Ambon in 1679.Footnote 67 This particular thunder-spade had been found way out in iron country, a place called Tomadano (possibly present-day Tondano) on the ‘eastern coast’ of Celebes. ‘In 1676, on a certain night, there passed a heavy storm’, Rumphius began the ambassador's tale. When a man from that town ‘went out to see where the lightning had struck, he found the spade, by a splintered tree, sunk a foot deep in a pothole of water that was not there before’. The thunder-spade that Rumphius purchased from the ambassador was, as it turned out, a spoil of war: soldiers from Tambocco took the weapon when they attacked Tomadano a year after its discovery.Footnote 68 This might partly explain why the ambassador was willing to sell the item to Rumphius. Because these objects were coveted for their power in war, they often became items to be collected and traded, prizes to be regifted, or materials to be reprocessed and refashioned.

Like with the rings, similar tales of thunder-spades circulated among witnesses of their material and magical manifestations. Rumphius heard one such tale from his ‘boy-servant’ (knechten) from southern Celebes. He was most likely one of the young slaves counted in Rumphius's household in the administration's annual population census.Footnote 69 ‘In that land, there was a river flowing with red water originating from a mountain of iron and copper’, the boy told Rumphius. Along this river, he and his uncle had found a thunder-spade in a groove in the ground where lightning had struck. ‘His uncle smelted it’, Rumphius wrote, ‘and made rings from it, which he wore on his forefinger to be lucky in war’.Footnote 70 Such refashioning of thunder-spades was common as long as one was lucky enough to find one. Rumphius heard from a ‘Chinese’ intermediary in Makassar that even the famous Arung Palakka, the ‘brave warrior’ of Bugis origin who had been a crucial VOC ally during the Makassar War (1666–1669), had seen thunder-spades during his military campaigns.Footnote 71 Having found one of these spades in Makassar, Palakka sought to refashion it to make a stronger kris, a dagger believed to be endowed with supernatural powers.Footnote 72 Significantly, it was also reported that during ‘the Javanese war’, the warrior wore these thunder-spades ‘on his body’ to protect himself from enemy attacks.Footnote 73 Similar stories emanated from a wide variety of local actors: a royal emissary, a slave boy and an ethnic Chinese inhabitant. These objects, coveted for their potency in war, drew their power from beliefs in their exceptional origins. While Rumphius did not necessarily believe in these accounts, his reliance on local information networks seems to have imbued his retellings with slippages that at times obscured cultural assumptions about his intermediaries’ social standing and blurred the boundaries between his and his intermediaries’ evocative portrayals.Footnote 74

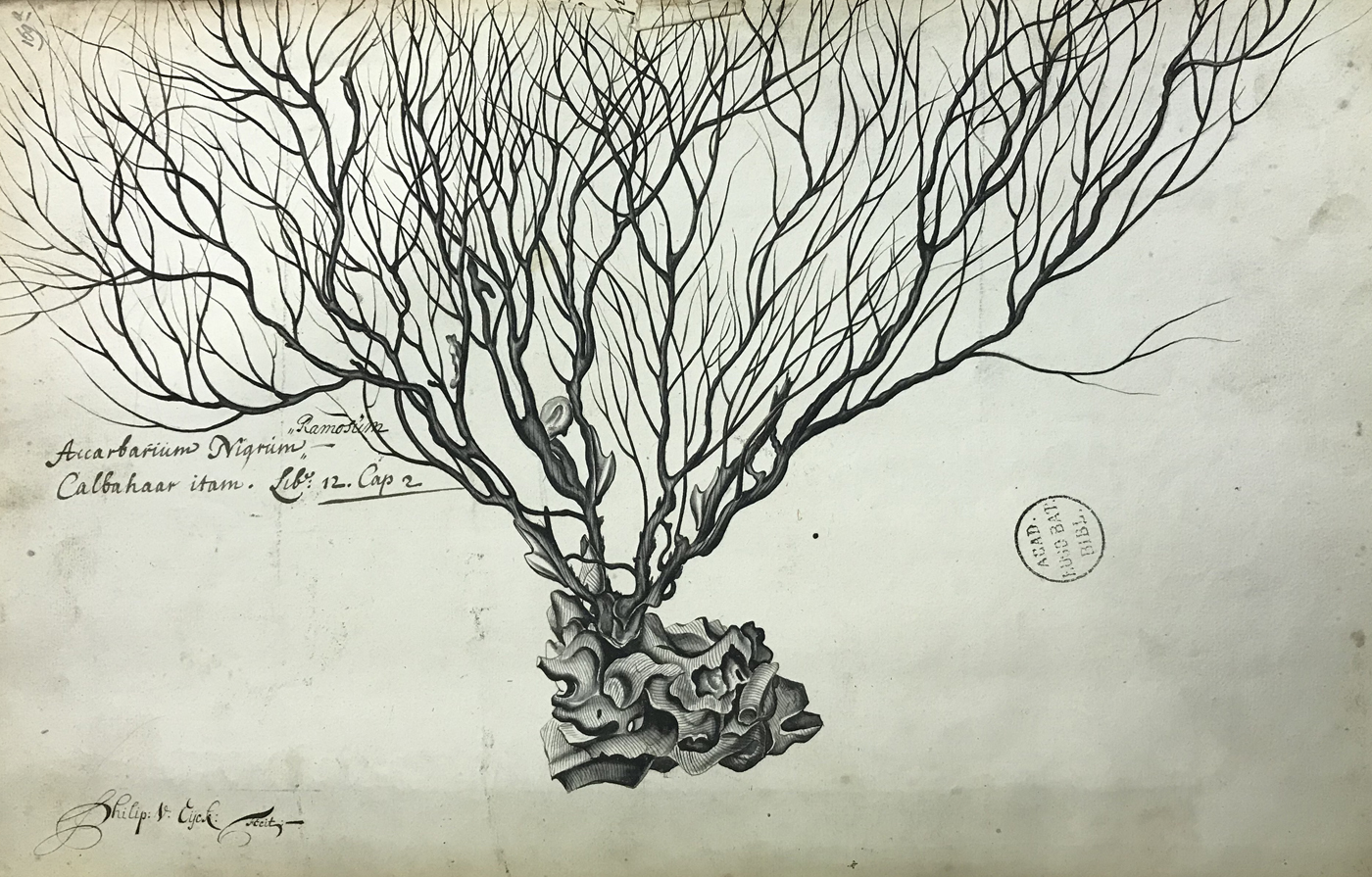

These tales and objects, collected from his numerous itinerant intermediaries coming from islands near and far, demonstrate the extent to which Rumphius drew on oral retellings of local beliefs to turn objects into curiosities. This is particularly apparent in his fascination with a type of black coral called acarbahar or calbahar (akar bahar, literally ‘roots of the sea’). In his Kruydboek, Rumphius included a lengthy description of the coral and how it was plied to make ornaments and weapons (Figure 4). Local people wore them ‘to be liberated from all kinds of magic, evil spells and noxious air’.Footnote 75 They were also used to make ‘curious kris-handles, steels and knives’, which were ‘more valuable’ than items of gold. While Rumphius detailed the coral's medicinal properties in the Kruydboek, he did not mention these in his Rariteitkamer or personal correspondence, preferring instead to underscore local beliefs in the coral's amuletic use. In his letter to Isaac de Saint Martin in Batavia, dated 15 September 1692, Rumphius wrote that the black coral called calbahar or acarbahar was ‘nowadays considered a Curiosity’.Footnote 76 People would ‘soften’ the branches and ‘bend’ them into bracelets which were believed to ‘hold the power to ward off all kinds of magic’. He made no mention of the coral's medicinal properties, selectively choosing to present information he believed would delight his fellow correspondent. Isaac de Saint Martin, who had been a lieutenant during Trunajaya's rebellion and, subsequently, a prominent administrator in Batavia, was an avid collector of books, as well as of weapons and Ambonese shells.Footnote 77 As if to fulfil his own role as a mediator of mediators from the outer island of Ambon to the administrative centre of Batavia, Rumphius sent Saint Martin a sample of the black coral: one that was ‘three feet and eight thumbs long’. On its branches, Rumphius had carefully hung ‘a small letter sealed and marked I.D.S.M.’.Footnote 78

Figure 4. Drawing of Accarbarium Nigrum Ramosum or Calbahar itam in the BPL 314 version of the Kruydboek (Book 12, Chapter 2). Leiden University Library Special Collections, BPL 314, G.E. Rumphius, Het Amboinsch Kruydboek, Book 12, f.169a.

Untangling the narrative of the ‘rare iron of Giri’

Rumphius's narratives about curiosities in his Rariteitkamer can obscure how the process of integrating various strands of information involved practices of inclusion and exclusion. To some extent, all narratives are selective, braided as they are from fragmentary threads of stories, facts, impressions and memories, read, heard and experienced: nuggets of knowledge consciously or unconsciously incorporated into a seeming whole with a particular intention in mind. Not all narratives in the form of a final published product can be traced back to their various sources and influences, let alone to the original intentions of the author. However, Rumphius's account of the iron rings of Giri in his Rariteitkamer does leave substantial clues that lead back to his inter-island networks, which involved information from his itinerant intermediaries, local VOC reports and testimonies in witnesses’ letters. They offer indications as to how and why he chose to present some and omit other information – decisions that follow a pattern characteristic to his descriptive methods and adhere to a general discourse about curiosities in Europe. Returning to the account of the Panembahan of Giri's iron amulets, this last section attempts to untangle Rumphius's entwined narrative about wars and wonders and looks closely at the selective process involved in translating ‘local’ knowledge into a curiosity.

Before launching into his narrative of the iron rings, Rumphius carefully noted that these rings were of ‘certain rare kinds, of which people tell both fabulous and truthful things’ – a common occurrence when ‘it is being disclosed by the natives’.Footnote 79 Already, the readers are given a clue as to how Rumphius may have learned about the beliefs and practices of a people living roughly 1,200 miles away on the island of Java. Without ever having travelled to Giri himself, he wrote, ‘Giri is a mountain and an airy city on the east side of Java’. In that city, Rumphius continued, there was a man called ‘the Penimbaan, who, living as Patriarch and Priestly King, through his bigotry and false miracles, was esteemed a holy man by the town's inhabitants’.Footnote 80 Among this man's many ‘deceptions’, Rumphius wrote, were ‘certain iron rings and bracelets’ that he ‘offered as gifts to strangers and to all who sought him’.Footnote 81 Having learned of this from his itinerant intermediaries, this suggests that they – as strangers to the town – might have received the rings as gifts, leaving open the possibility of their material circulation in the archipelago. Rumphius, as it happens, described the object as if he had seen it himself: ‘some of the rings are thin and completely hollow on the inside, so that they would float on water, which the unknowing populace considers a miracle’. These rings, moreover, were assumed to be endowed with powers of permanence and invulnerability, as they were believed to resist rust and were filled with clumps of ‘holy earth’ from the Panembahan's ancestral graves. But ‘upon more detailed research’, Rumphius assured his readers, ‘one finds that these are all superstitions and Moorish deceptions’.Footnote 82

Not unlike his other investigations of the archipelago's rings, Rumphius's research into these claims involved inquiring into the object's origins and use at a distance. Moreover, to provide support for his debunking, he again relied on specific information that only his itinerant intermediaries could have provided. He learned that the Panembahan had created these rings out of ‘rusted nails’ from his own ‘temple’. These nails were made of iron said to be called bessi keling (literally ‘Keling iron’) originating from the Coromandel Coast.Footnote 83 Such information must have sounded familiar to Rumphius. During the 1660s and 1670s, there was a dramatic increase in VOC imports of iron from the Coromandel Coast, as the company found their existing supply insufficient for manufacturing weapons.Footnote 84 While Rumphius most likely knew about these broader maritime networks, the specific connection between the refashioning of the temple's nails into rings and the nails’ material origins from the Indian subcontinent could have only come from his itinerant intermediaries.

From them, Rumphius also learned that like other rings traded in the archipelago, men wore them as amulets ‘on the forefinger or on the thumb, where they grip the kris and other weapons, in order to be lucky in war’. The specificity of the ring's function as a conduit of power for other sacred weapons suggests that Rumphius's intermediaries may have been experienced soldiers who had fought in Java as allies of the VOC. One Javanese chronicle mentions the presence of Ambonese soldiers in the battle of Kadiri; and an Ambonese captain named Jonker, along with the famous Bugis warrior Arung Palakka, were mentioned to have been crucial players in the battles leading up to Trunajaya's death.Footnote 85 However, none of these figures were reported to have fought in the battle of Giri. Making an important transition from the narrative of the iron rings to one of the battle itself, Rumphius wrote,

I trust that they use [these rings] against their countrymen, for they have no power against the Dutch, as the aforementioned Moorish Pope experienced to his misfortune, when he, in the year 1680, on 25 April, came upon our people with his clan of 50 strong and combative men.Footnote 86

Here, details of the battle emerge: ones that are remarkably similar to official VOC reports based on Dutch and Javanese letters, but with significant omissions and changes.

In Rumphius's account of the battle, the conflict was rooted in the Panembahan's refusal to pay homage to the king and in his secret pact with Trunajaya. When the battle began, ‘the Papist came boldly upon our people with his compatriots and killed a German Captain with 15 soldiers’, Rumphius wrote, using a religious trope that would have sounded familiar to his intended readers. The battle turned, however, when the Panembahan, careless and ‘hot from drink’, was ‘immediately shot in the knee with a musket’. Thus immobilized, he was carried to a safe house at the top of the mountain where, in the middle of the night, an unnamed man from the nearby island of Madura killed him with a small dagger. The next day, Amangkurat II was said to have executed the Panembahan's two eldest sons, ‘uprooting the entire line of the holy family, to the astonishment of the whole of Java’.Footnote 87

The Batavian Dagh-register of 1680 includes two separate accounts of the battle of Giri. The first is a scribal summation of a letter from the Dutch commander Jacobus Couper who oversaw military operations for Java's eastern coast and participated in the battle.Footnote 88 The second is a Dutch translation of a Javanese letter from Amangkurat II, recounting the circumstances of Trunajaya's rebellion and the events of the battle.Footnote 89 Both of these mediated accounts confirm the details provided in the Rariteitkamer. The root of the conflict is imputed to the alliance of the Panembahan with Trunajaya and the former's refusal to pay obeisance to the king.Footnote 90 They all mention the ‘ferocity’ with which the Panembahan gave battle against the allied forces of the Dutch and the Javanese.Footnote 91 The unnamed ‘German captain’ who was killed in the midst of the battle is said in both accounts to be Captain Casper Altemeyer. Pointedly, that the Panembahan was wounded in the right knee is attested by both Couper and Amangkurat II. Given the uncanny correspondence between Rumphius's narrative and official VOC accounts, it is likely that Rumphius derived many of these details from his administrative networks. In fact, Couper, whose original letter would form the backbone of Batavia's account of the battle, had also been writing to the local Council of Ambon, updating its members on the events of Trunajaya's rebellion, as attested to by a letter now preserved in the Ambonese Dagh-register of 1680.Footnote 92

However, Couper's original letter to the High Government of Batavia, dated 14 May 1680, contains two dramatic scenes that were not included in the Rariteitkamer.Footnote 93 They both pertained to local beliefs and rituals of power, the type of information that would have greatly interested Rumphius. Couper reported that in order to rally the men for battle, the Panembahan had performed a ‘strange’ ritual:

[He] stuck a great bowl full of bezoar stones into the fire, saying [to his men], after faint murmurings under his breath: in the smoke I have spoken with the spirit of the king [Amangkurat I] who has my promise that there shall pass 1000 spirits among my sons, so that no enemy shall be able to do them harm. So you may gather with courage and attack the enemy without any fear. For out of my line shall a king be born.Footnote 94

According to the letter, this galvanized the men of Giri as they gave ‘furious’ battle against the Dutch and the Javanese. Another significant detail not included in Rumphius's account is the importance of the Panembahan's kris. Couper reported that when the Panembahan was finally killed, the Javanese made sure to take his kris, named Calamoenjang, because according to Javanese ‘superstition’, it embodied the powers and ‘virtues’ of its owner.Footnote 95 The Javanese account likewise emphasized the importance of taking the Panembahan's kris, which was not considered merely a spoil of war, but a transference of power from the Panembahan's family line to the royal line of Mataram.Footnote 96

Neither detail about the supernatural aspects of the battle is found in Rumphius's Rariteitkamer, while no other source but Rumphius mentions the use of iron rings as an amuletic weapon in war. The information specific to the iron rings, as laid out in the first part of the chapter, came from Rumphius's itinerant intermediaries, who were aware of the beliefs attached to the rings and may have even seen these objects up close, but likely did not participate in the battle itself. The information specific to the battle in the second part of the narrative was based on VOC channels connecting Ambon and Batavia. While these administrative accounts detail the events of the battle and the role of local beliefs in its proceedings, they do not explicitly mention the use of amuletic rings. Faced with the fact of the rings’ existence but without evidence of their use in battle, Rumphius resorted to speculation. ‘I trust that they use them against their countrymen’, he wrote, ‘for they have no power against the Dutch’ (my emphasis). Behind this expression of imperial superiority, one sees the possibility of teasing out how ‘magic’ rings, so widely circulated in the archipelago, maintained their local credibility after one's defeat in war. Rumphius intimates that it was a matter of having a shared cosmology between the parties involved – among one's own countrymen – that accorded internal consistency to these beliefs. Indeed, as historians have shown, local island kingdoms have long incorporated the defeated party's weapons and manuscripts into their own collections of sacred objects, just as the Javanese had done by taking the Panembahan's kris.Footnote 97 For local sovereigns, possessing these objects was a means by which to absorb, accumulate and preserve power. For Rumphius, however, how these objects faired in the test of battle against ‘the Dutch’ made for a more interesting narrative. Seeking to turn this object into a curiosity, then, Rumphius not only incorporated local beliefs but also lent the object a veneer of historicity by speculating on its supposed use and failure in a historic battle. ‘False miracles’ were just as curious as miracles, he seemed to say, and the iron ring of Giri was not only a wondrous object but also a curious artefact, one worthy of a place in the imaginary Wunderkammer of his intended readers. These omissions, particularly with respect to the Panembahan's kris, highlight the extent to which the narrative function of the battle was simply to heighten the uniqueness of the rings as curiosities.

While details of the battle were similar in all accounts, omissions and additions pertaining to its supernatural aspects demonstrate to what extent ‘local’ information underwent its own complicated circuits of transmission within the archipelago. Rumphius was not just a transmitter of information: he was a mediator, who used specific narrative strategies to bridge the gap between his readers and the information he had acquired from other islands. His chapter on the ‘rare iron of Giri’ is an example of how a local object was rendered into a curiosity based on strands of information selectively culled from separate networks of knowledge, a composite taken from indigenous and imperial accounts. In this particular instance, the creative and discriminating role of the individual naturalist comes to the fore, years before the crystallization of a modern colonial discourse.Footnote 98 Interestingly, while these rings were represented as curiosities in text, they did not have much commercial traction in Europe. This shows how a naturalist's attempts to construct an image of a curiosity from the Indies did not necessarily turn the object itself into a commodity for the European marketplace. As catalogues of East Indies collections show, what attracted European collectors of curiosities were mainly seashells, crustaceans and insects – not magic rings.Footnote 99 What this may perhaps demonstrate is the ambivalent connection between the discursive and commercial value of curiosities. Indeed, in the case of the iron rings, it seems that the naturalist was raising the discursive value of the object, not in an attempt to sell the object itself, but to render the book more commercially attractive. As a textual Wunderkammer of curious objects fleshed out with equally curious information and images, the Rariteitkamer was a book not only about real things but also about the truthful and the fabulous tales spun about them. True or false, Rumphius judged that the value of such curious information – as the Panembahan's ‘false miracles’ – would attract ‘the eyes of Enthusiasts’.

Conclusion

This article opened with the question of how one man living on one island came to acquire knowledge of other islands in the archipelago. Trying to answer this question has involved not only a careful tracing of information and intermediaries, but also a recognition of how Rumphius negotiated boundaries of difference in distinct contexts of knowledge production. Embedded in the contextual layering of this essay are Rumphius's contradictory depictions of Muslim figures, as praised experts on the one hand and as deceptive papists on the other. This demonstrates how his perceptions and projections of difference shifted dramatically based on the circumstances of his experiential and authorial positions; that is, from his role as a naturalist who relied on local experts on the ground to his role as a narrator dramatizing distant events to his even more distant readers. Furthermore, I have tried to foreground the importance of recognizing the complex localized trajectories of mediated information, as it travelled in both oral and textual forms along indigenous and imperial networks. Perhaps this is a useful reminder that while texts, images and objects are what buttress present understandings of the past, it was often the irretrievable channels of oral communication that formed the daily experiences of travellers, administrators and merchants in different parts of the early modern world. As Robert Darnton suggested, in order to write a history of an information society, one must work with the premise that such a history would be incomplete without considering both aspects of verbal communication, the oral and the written.Footnote 100 While fixity of oral communication is difficult to come by, historians have shown how recapturing its remnants is indeed possible by following the ‘infinitesimal traces’, ‘slender clues’ and ‘negligible details’ as they are found in texts: granular fragments that reveal the textural thickness of an information society.Footnote 101 While this article provides only a glimpse of the people Rumphius engaged with, his texts abound with such traces of cross-cultural interactions, opening up the possibility of examining the complex dynamics of a diverse information society that spanned many islands in the archipelago.

To conclude, this article has sought to trace the inter-island information networks of one man who, through his many indigenous, administrative and commercial connections, was able to collect and translate local knowledge for his European readers. His local intermediaries ranged from itinerant merchants and provincial noblemen to royal ambassadors and household slaves. Rumphius's access to such a range of individuals was mainly due to his position as a VOC administrator on an island famous for being an important commercial entrepôt in the eastern archipelago. While he did not always approve of local beliefs, he continued to draw on them to write about objects of power that circulated in the islands. Rumphius combined multiple versions of events – from oral retellings to written reports – to organize information emanating from different islands into his particular description of wonders: Ambonese curiosities. While this article has shed light on the complex nature of his networks, perhaps such projections of an Amboinsche world for an archipelago whose centres lay as much in Batavia as in Mataram, Aceh and Makassar should make one wary of the long-lasting authorial powers of mediation. After all, Rumphius was one man whose world was but an island among the tens of thousands in the archipelago.