An adequate and balanced supply of α-tocopherol is important for proper growth and an effective immune response( Reference Kono and Arai 1 ). Furthermore, α-tocopherol acts as an antioxidant in the body, as well as in the feed( Reference Jensen, Engberg and Hedemann 2 ). Mink feed is characterised by a high content of protein, a low content of carbohydrates and a high content of fat, often polyunsaturated of marine origin. The demand for antioxidants is therefore considered to be high( Reference Hymøller, Clausen and Jensen 3 ). The typical source of supplemental α-tocopherol is synthetic manufactured racemic mixture (all-rac) but RRR-α-tocopherol is also available as a feed additive. α-Tocopherol exists in eight different isomeric configurations including four with 2R configuration (RSS, RRS, RSR, RRR) and four with 2S configuration (SRR, SSR, SRS, SSS). The RRR isomer is the only form of α-tocopherol occurring in nature( Reference Kono and Arai 1 ), whereas α-tocopherol used for feed additives consists of a racemic mixture of all eight stereoisomers. In commercial vitamin mixtures, all-rac-α-tocopherol is typically acetylated, in order to stabilise its functional phenol group during storage, and added to rations as all-rac-α-tocopheryl acetate. This acetylated form of α-tocopherol must be hydrolysed before it can be absorbed from the gastro-intestinal tract( Reference Jensen, Engberg and Hedemann 2 ), but in mink hydrolysis is not the limiting factor in the absorption of α-tocopherol as opposed to, for example, newly weaned piglets( Reference Hedemann and Jensen 4 , Reference Hedemann, Clausen and Jensen 5 ).

The biopotency of the RRR stereoisomer of α-tocopherol is higher than the biopotency of the synthetic stereoisomers of α-tocopherol and the ratio of 1·36:1 in biopotency of RRR-α-tocopheryl acetate to all-rac-α-tocopheryl acetate is generally reported when working with α-tocopherol supplementation( Reference Burton, Traber and Acuff 6 ). However, several studies have indicated that neither the biopotency of α-tocopherol stereoisomers nor the bioavailability between them is constant, but rather dose- and dose-time dependent and differs significantly between organs and tissues( Reference Jensen, Nørgaard and Lauridsen 7 , Reference Blatt, Pryor and Mata 8 ). In rats, biodiscrimination against the different stereoisomers in plasma and tissues largely reflects the specific stereoisomer biopotency( Reference Jensen, Nørgaard and Lauridsen 7 ). In humans, only 2R-α-tocopherols are considered to have biological activity, and thus a ratio of 2:1 is used( Reference Council and Council 9 ). A recent study on the concentration of stereoisomers of α-tocopherol in the human infant brain showed severe discrimination against all synthetic stereoisomers of α-tocopherol in this organ( Reference Kuchan, Jensen and Johnson 10 ). In addition, it has been reported that RRR-α-tocopherol is the predominant stereoisomer of α-tocopherol in human breast milk( Reference Gaur, Kuchan and Lai 11 ). Rats accumulate a relatively high amount of 2S stereoisomers( Reference Jensen, Nørgaard and Lauridsen 7 ) and cannot be considered as an appropriate model for humans in this respect. Mink’s accumulation of stereoisomers of α-tocopherol in plasma and tissues differs from rats, and seems to be more similar to humans( Reference Jensen, Nørgaard and Lauridsen 7 ). The aim of this study was to determine the distribution of α-tocopherol stereoisomers in plasma and organs from mink fed different levels and sources of α-tocopherol.

Methods

This study complied with the Danish Ministry of Justice Law No. 474 (15 May 2014) concerning experiments with animals and care of animals used for experimental purposes and was conducted under the approval of the Danish Veterinary and Food Administration under the Danish Ministry of Environment and Food. The studies were carried out at the Copenhagen Fur Research Centre in Holstebro, Denmark, between July and November 2015.

Animals, housing and feeding

In the present study, forty brown male mink were used. All mink were traditionally housed in wire netting cages in pairs of one male and one female throughout the study. All animal facilities were sheltered under permanent outdoor sheds. Basic rations were wet mink feed rations composed of industrial fish (30 %), poultry (15 %), grain (barley/wheat) (15 %), fish silage (6 %), soya oil (6 %), fish offal (5 %), potato protein/maize gluten (5 %), lard (3 %), Hb meal (2 %), minerals and synthetic methionine (1 %) and water (12 %). The protein:fat:carbohydrate ratio was 30:55:15 on energy basis. Basic diets were mixed before the studies, α-tocopherol was added according to the treatment plans and subsequently stored at –18°C in 5-kg plastic bags. The necessary number of bags of feed were thawed daily and fed to the respective treatment groups. The mink were fed once a day and had ad libitum access to water. α-tocopherol as either all-rac-α-tocopheryl acetate or RRR-α-tocopheryl acetate was kindly provided by Provia A/S.

Treatments and study design

The study was carried out as a dose–response study with daily supplementation with different doses of all-rac-α-tocopheryl acetate or RRR-α-tocopheryl acetate in the feed. The mink were born in the first week of May, weaned on 1 July 2015 and male and female mink were paired and placed in cages to habituate them to the cage mate and the housing facilities. On 15 July 2015, the mink were randomly assigned to four treatment groups: no added α-tocopherol in the feed (ALFA_0), 40 mg/kg feed RRR-α-tocopheryl acetate (NAT_40), 40 mg/kg feed all-rac-α-tocopheryl acetate (SYN_40) and 80 mg/kg feed all-rac-α-tocopheryl acetate (SYN_80). Analysed contents of total α-tocopherol and distribution of stereoisomers of α-tocopherol in the diets by mid-November are shown in Table 1.

Table 1 Analysed content of α-tocopherol (n 2) and distribution of stereoisomers of α-tocopherol in diets

NAT_40, 40 mg/kg RRR-α-tocopheryl acetate; ALFA_0, control diet with no α-tocopherol; SYN_40, diet containing 40 mg/kg all-rac-α-tocopheryl acetate; SYN_80, diet containing 80 mg/kg all-rac-α-tocopheryl acetate.

Sample material

In mid-November 2015, the mink were fasted for 12 h and subsequently euthanised in CO2. A blood sample was taken by heart puncture, the mink were pelted and liver, heart, lungs, brain and a sample of abdominal fat collected. All sample material was stored at –18°C until analysis.

Chemical analyses

Chemical analyses for contents of α-tocopherol and stereoisomers of α-tocopherol were performed at the Department of Animal Science, Aarhus University. All samples and standard vitamin solutions were protected from light during preparation. α-Tocopherol contents of plasma, organ and diet were determined as described by Jensen et al.( Reference Jensen, Nørgaard and Lauridsen 7 ). Organ samples were homogenised by Ultra Turrax (IKA Labortechnik) in an ice bath and, like plasma and diet samples, precipitated in ethanol and methanol, saponified with potassium hydroxide and extracted in heptane. Separation and quantification of α-tocopherol was carried out by HPLC as described by Jensen et al.( Reference Jensen, Nørgaard and Lauridsen 7 ). The stereo-chemical composition of α-tocopherol in plasma, organs and diet samples was determined after methylation of stereoisomers into their methyl esters and subsequent separation by chiral HPLC, as described by Jensen et al. ( Reference Jensen, Nørgaard and Lauridsen 7 ). Results are reported as the ratio of the observed stereoisomer among five peaks and the concentration determined by calculation of each stereoisomer concentration from total α-tocopherol. Recovery of total α-tocopherol was 96 % with a CV (%) of 2·7, whereas recovery of the individual stereoisomers varied from 95·3 to 100·8 % with CV (%) varying from 1·2 to 7·9. Data were expressed per wet weight of tissue.

Statistical analyses

The statistical power was analysed in SAS® by Proc Power. The statistical power was >0·999 for all comparisons. Thus, the high statistical power in the present study avoided a type II error (not detecting the true difference) and ensured sufficient reliability for significant statistical differences. Differences between treatments within organ and between stereoismers in the same diets were analysed in SAS® MIXED models (SAS Institute Inc.) using the following model: Y ij =µ+α i +e ij , where Y ij was the dependent variable (total α-tocopherol content and stereoisomer percentage), α i the effect of treatment i and e ij the random residual error. Differences in total α-tocopherol content were analysed using the model Y ij =µ+β i +e ij , where Y ij was the dependent variable (total α-tocopherol, stereoisomer percentage), β i the effect of organs i and e ij the random residual error. Random effects were assumed normally distributed with mean value 0 and constant variance e∼N(0,σ 2). Results are presented as least squares means and differences considered statistically significant if P≤0·05.

Results

The diets fed to different treatment groups were analysed to confirm the content of α-tocopherol and distribution of α-tocopherol stereoisomers in the diets. Results of α-tocopherol and stereoisomer distribution in different treatment groups are shown in Table 1 and are in agreement with the planned contents of α-tocopherol in the supplemented treatment groups.

The highest and lowest contents of total α-tocopherol in plasma, organs and abdominal fat were found in SYN_80 and ALFA_0, respectively (P≤0·05). No significant differences were found in total α-tocopherol contents between SYN_40 and NAT_40 in plasma, organs or abdominal fat (Table 2). As expected, the highest proportion of RRR-α-tocopherol was found in NAT_40 in all organs, abdominal fat and plasma (P≤0·05). The proportion of RRR-α-tocopherol in ALFA_0 was lower than the NAT_40 in all organs, abdominal fat and plasma (P≤0·05); however, the proportion of RRR-α-tocopherol in ALFA_0 was higher than in SYN_80 and SYN_40 (P≤0·05). In liver and brain no significant differences were found in RRR-α-tocopherol proportion between SYN_80 and SYN_40, whereas SYN_40 had higher RRR-α-tocopherol proportion than SYN_80 in plasma, heart, lungs and abdominal fat (P≤0·05, Table 2). In addition, the proportion of the synthetic 2R stereoisomers and the Σ2S stereoisomers was higher in plasma, organs and abdominal fat in SYN_80 and SYN_40 compared with ALFA_0 and NAT_40 (P≤0·05). The liver was the organ that contained the highest proportion of Σ2S-α-tocopherol stereoisomers (P≤0·05, Table 2).

Table 2 Total α-tocopherol content and distribution of α-tocopherol stereoisomers in plasma, organs and abdominal fat (n 10)

NAT_40, 40 mg/kg RRR-α-tocopheryl acetate; ALFA_0, control diet with no α-tocopherol supplement; SYN_40, diet containing 40 mg/kg all-rac-α-tocopheryl acetate; SYN_80, diet containing 80 mg/kg all-rac-α-tocopheryl acetate.

a,b,c,d Mean values within a column with unlike superscript letters were significantly different (P≤0·05).

W,X,Y,Z Mean values within a row with unlike superscript letters were significantly different (P≤0·05).

Comparison of α-tocopherol stereoisomers proportion within the plasma, organs and abdominal fat within the same diets is summarised in Table 2. The proportion of α-tocopherol stereoisomers in plasma, brain, heart, lungs and abdominal fat showed the following order: RRR>RRS, RSR, RSS>Σ2S, regardless of α-tocopherol supplement. However, a different pattern was observed in the liver in SYN_40 and SYN_80; here, Σ2S-α-tocopherol accounted for the highest proportion of α-tocopherol stereoisomers, intermediate values for RRR-α-tocopherol and lowest for the synthetic 2R-α-tocopherols. In addition, in ALFA_0 and NAT_40, the proportion of α-tocopherol stereoisomers in liver showed the following order: RRR>Σ2S>RRS, RSR, RSS.

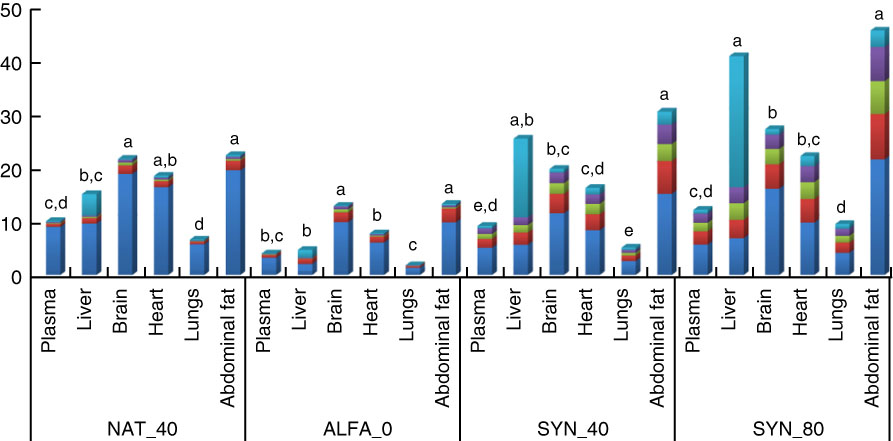

The α-tocopherol content and distribution of stereoisomers between plasma, organs and abdominal fat within diets containing different α-tocopherol amount is shown in Fig. 1. In the ALFA_0 and NAT_40, the highest amount of total α-tocopherol was observed in brain and abdominal fat; however, in diets containing the SYN_80 and SYN_40, the highest amount of α-tocopherol was observed in liver and abdominal fat (P≤0·05). Regardless of α-tocopherol supplement, lungs showed the lowest amount of total α-tocopherol (P≤0·05).

Fig. 1 Total-α-tocopherol content and stereoisomer distribution of plasma (μg/ml), different organs (μg/g) and abdominal fat (μg/g) within the same diets. a,b,c,d,e Mean values within the same diets with unlike letters were significantly different (P≤0·05). NAT_40, 40 mg/kg RRR-α-tocopheryl acetate; ALFA_0, control diet with no α-tocopherol supplement; SYN_40, diet containing 40 mg/kg all-rac-α-tocopheryl acetate; SYN_80, diet containing 80 mg/kg all-rac-α-tocopheryl acetate. ![]() , Σ2S;

, Σ2S; ![]() , RSS;

, RSS; ![]() , RSR;

, RSR; ![]() , RRS;

, RRS; ![]() , RRR.

, RRR.

Discussion

The high proportion of RRS-α-tocopherol and Σ2S-α-tocopherol in the ALFA_0 diet most likely reflects the presence of these stereoisomers in the poultry and industrial fish used and thus originate from the all-rac-α-tocopheryl acetate fed to these animals. The present study showed a severe discrimination against systemic circulation and take up of synthetic stereoisomers of α-tocopherol into organs. Irrespective of α-tocopherol supplement, the RRR-α-tocopherol was the dominant stereoisomer in the plasma, organs and abdominal fat. The results revealed that non-RRR-α-tocopherol remained in the liver, compared with RRR-α-tocopherol, which was preferentially released from the liver to the plasma (Table 2). The high proportion of non-RRR-α-tocopherol in the liver indicated the role of liver in elimination of non-RRR-α-tocopherol. These results agreed with Kaneko et al. ( Reference Kaneko, Kiyose and Ueda 12 ), who found the important role of liver in degradation of radiolabelled SRR-α-tocopherol. Kaneko et al. ( Reference Kaneko, Kiyose and Ueda 12 ) studied the metabolism of α-tocopherol stereoisomers in rat and reported that radioactivity derived from SRR-α-tocopherol reached its maximum level 24 h after the dosage, and that derived from RRR-α-tocopherol reached maximum at 48 h; therefore, they concluded that SRR-α-tocopherol eliminated rapidly from the liver. An early study by Ingold et al.( Reference Gaur, Kuchan and Lai 13 ) showed a similar preferential uptake of RRR-α-tocopheryl acetate over SRR-α-tocopheryl acetate in male Sprague–Dawley rats. Similarly, Jensen et al. ( Reference Jensen, Nørgaard and Lauridsen 7 ) showed discrimination against all synthetic stereoisomers of α-tocopheryl acetate in male Wistar rats, with the most severe discrimination found to be against Σ2S-stereoisomers of α-tocopherol. In the study by Ingold et al. ( Reference Ingold, Burton and Foster 13 ), the strongest discrimination of all organs against the SRR-α-tocopherol stereoisomer was found in rat brain in agreement with the findings of the present study. In rats, the discrimination against the SRR-α-tocopherol stereoisomer was shown by Ingold et al. ( Reference Ingold, Burton and Foster 13 ) to be initiated already in the gut, probably owing to incomplete hydrolysis of the acetate group of α-tocopheryl acetate( Reference Hedemann and Jensen 4 ), a step that, in previous studies, has been shown not to be limiting in mink( Reference Hedemann and Jensen 4 , Reference Hedemann, Clausen and Jensen 5 ).

The liver is considered to be the main site of the preferential biodiscrimination in favour of α-tocopherol with 2R configuration, owing to the abundant presence of α-tocopherol transfer protein (α-TTP) in this tissue( Reference Hosomi, Arita and Sato 14 ). Consequently, the liver builds up high concentrations of synthetic stereoisomers, especially those with 2S configuration. The key role of liver in elimination of Σ2S-α-tocopherol has been proven already( Reference Blatt, Pryor and Mata 8 ), but the high proportion of Σ2S stereoisomers in livers from NAT_40 and ALFA_40 indicates higher accumulation of at least a part of the Σ2S stereoisomers in the liver. The high proportion of non-RRR-α-tocopherol in plasma and organs other than liver might reflect that α-TTP accepts other 2R-α-tocopherol stereoisomers than RRR-α-tocopherol. In addition, it is likely that organs and abdominal fat uptake of 2R and Σ2S-α-tocopherol stereoisomers follow the mechanisms of lipid uptake. In agreement with our finding, Hosomi et al. ( Reference Hosomi, Arita and Sato 14 ) demonstrated the tissue uptake of α-‐tocopherol by a variety of non-specific mechanisms linked to clearance of chylomicrons by lipoprotein lipase during the first pass before hepatic uptake.

Although the amount of total α-tocopherol in brain increased from 19·9 to 27·3 µg/g in SYN_40 and SYN_80, respectively, the RRR-α-tocopherol proportion did not decrease. This severe discrimination against synthetic stereoisomers of α-tocopherol in the brain of mink found in the present study is in agreement with a recent study on the distribution of α-tocopherol stereoisomers in the human infant brain by Kuchan et al. ( Reference Kuchan, Jensen and Johnson 10 ). In their study, Kuchan et al. ( Reference Kuchan, Jensen and Johnson 10 ) showed an almost complete absence of the seven synthetic stereoisomers of α-tocopherol in the brain of infants (0·2–1·5 μg/g brain tissue) in contrast to the RRR stereoisomer (7–15 μg/g brain tissue). However, in that study the intake of α-tocopherol or the stereoisomeric composition was not known. This supposedly indicates that the RRR stereoisomer of α-tocopherol is essential for the development of the brain, because biological discrimination and biological importance are usually intimately linked in the body( Reference Kuchan, Jensen and Johnson 10 ).

Generally, the difference between the RRR-α-tocopherol and the non-RRR-α-tocopherol group (Table 2) supported that non-RRR-α-tocopherol has poor retention in the different organs compared with RRR-α-tocopherol. In agreement with our findings, Kaneko et al. ( Reference Kaneko, Kiyose and Ueda 12 ) reported that urinary and faecal excretion of radioactivity derived from SRR-α-tocopherol was significantly greater than that derived from RRR-α-tocopherol. On the basis of Table 1, the diets containing SYN_80 and SYN_40 had high amounts of non-RRR-α-tocopherol; however, lower proportions of non-RRR-α-tocopherol were observed in the plasma, organs and abdominal fat, indicating a preferential exclusion of these stereoisomers. It has been shown that all-rac-α-tocopherol are metabolised to 2,5,7,8-tetramethyl-2-(2′-carboxyethyl)-6-hydroxychroman faster than RRR-α-tocopherol( Reference Traber, Elsner and Brigelius-Flohé 15 ). Traber et al. ( Reference Traber, Elsner and Brigelius-Flohé 15 ) also reported the higher excretion rate of all-rac-α-tocopherol than of RRR-α-tocopherol.

In the present study, the proportion of the RRR stereoisomer of α-tocopherol in plasma and tissues decreased as expected when mink were fed diets containing all-rac-α-tocopheryl actetate compared with NAT_40 and ALFA_0, and also when all-rac-α-tocopheryl actetate increased from 40 to 80 mg/kg feed. The exception was the brain, where the proportion of RRR-α-tocopherol was constant between mink on SYN_40 and SYN_80 diets. This implies that the proportion of natural and synthetic stereoisomers of α-tocopherol is not constant, but dependent on the dose of α-tocopherol, vitamin E source (SYN v. NAT) and the target organ( Reference Blatt, Pryor and Mata 8 ). RRS-α-tocopherol is the synthetic 2R stereoisomer with a stereochemical configuration most similar to RRR-α-tocopherol and the synthetic stereoisomer occurring with the highest proportion after RRR-α-tocopherol. This reveals the importance of the stereochemical configuration as a determinant for the distribution of α-tocopherol stereoisomers for biopotency. Thus, Weiser & Vecchi( Reference Weiser and Vecchi 16 ) showed in the classical rat resorption gestation test that RRS-α-tocopherol was the α-tocopherol stereoisomer with the highest biopotency after RRR-α-tocopherol. The present study shows that discrimination of α-tocopherol stereoisomers is complex and varies between organs within species.

Conclusions

The distribution of α-tocopherol stereoisomers is dependent on dose and source of α-tocopherol. Increasing the amount of synthetic α-tocopherol stereoisomers in the diet decreased the proportion of RRR-α-tocopherol in all organs, abdominal fat and plasma, whereas the proportion of synthetic 2R-α-tocopherol increased in plasma and organs, with RRS-α-tocopherol occurring with the highest proportion. However, the proportion of Σ2S-α-tocopherol was unaffected by SYN_40 and SYN_80 and remained low in plasma and all organs with the exception of liver. Similarly, the brains proportion of RRR-α-tocopherol was unaffected whether the mink were fed diet SYN_40 or SYN_80. The results demonstrated that different organs discriminate stereoisomers of α-tocopherol to a different extent.

Acknowledgements

Laboratory technician E. L. Pedersen is acknowledged for carrying out the chemical analysis and collecting organs and blood for analysis.

The study was supported by the foundation for research in fur-bearing animals under Copenhagen Fur, Denmark. The funder had no role in the design, analysis or writing of this article.

L. H. contributed to laboratory analyses, data analysis, interpretation of the findings and writing the final manuscript. S. L. was involved in interpretation of the findings, data analysis and writing the final manuscript. T. N. C. contributed to data analysis, interpretation of the findings and writing the final manuscript. S. K. J. contributed to formulating the research questions, study design, laboratory analyses, data analysis, interpretation of the findings and writing the final manuscript.

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.