The biochemical function of folate involved in one-carbon metabolism critical for cellular proliferation and nuclear DNA repair has been well documented (Shane, Reference Shane and Bayley1995). In the last decade, growing literature evidence suggests another potential role of folate on antioxidant action (Nakano et al. Reference Nakano, Higgins and Powers2001; Mayer et al. Reference Mayer, Simon and Rosolova2002; Rezk et al. Reference Rezk, Haenen, van der Vijgh and Bast2003; Coppola et al. Reference Coppola, D'Angelo and Fermo2005). Numerous investigations have shown that folate deprivation elevated pro-oxidant homocysteine levels (Huang et al. Reference Huang, Hsu, Lin and Yang2001), impaired antioxidant enzymatic activities (Chen et al. Reference Chen, Huang, Wei and Liu2001; Huang et al. Reference Huang, Hsu, Lin and Yang2001), increased reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation and lipid peroxidation (Chern et al. Reference Chern, Huang, Chen, Cheng and Liu2001). However, the basis for folate status and oxidative insults is unclear. Folic acid has been proposed to scavenge peroxyl radicals, azide radicals and hydroxyl radicals in an in vitro radical reaction model system (Joshi et al. Reference Joshi, Adhikari, Patro, Chattopadhyay and Mukherjee2001). Particularly, the intracellular superoxide-scavenging capability of folic acid was observed in various pro-oxidant-challenged cells such as homocysteine thiolactone-treated HL60 cells (Huang et al. Reference Huang, Huang, Lin, Hung and Lu2002) and 7-ketocholesterol-treated U937 cells (Huang et al. Reference Huang, Yaong, Chen and Lu2004). Increased folate intake was found to improve endothelial function in patients with coronary artery disease, which is largely independent of homocysteine lowering action. Instead, reduction of intracellular endothelial superoxide may have contributed to the effect of folate (Doshi et al. Reference Doshi, McDowell and Moat2001). The studies mentioned earlier raise the potential question about the corresponding mechanism responsible for folate's superoxide-scavenging capability.

The mitochondrial (mt) electron transport chain has been recognized as a major intracellular source of superoxide anion generation (Ksenzenko et al. Reference Ksenzenko, Konstantinov, Khomutov, Tikhonov and Ruuge1983; Turrens et al. Reference Turrens, Alexandre and Lehninger1985). When superoxide production exceeds the capacity of detoxification and repair pathways, oxidative damage to mt protein, DNA and phospholipid occurs, which may further disrupt electron transport chain and constitute a ROS-generated vicious cycle leading to apoptotic signalling and cellular death (Cadenas & Davies, Reference Cadenas and Davies2000; Ravagnan et al. Reference Ravagnan, Roumier and Kroemer2002). The increased oxidative stress is also critical in the accumulation of the most abundant mtDNA mutations, a large-scale deletion of 4977 bp in ageing human tissues (Cortopassi et al. Reference Cortopassi, Shibata, Soong and Amheim1992) and 4834 bp large deletion in mtDNA (mtDNA4834 deletion) in ageing rodent tissues (Edris et al. Reference Edris, Burgett, Stine and Filburn1994). This mtDNA large deletion removes 30 % of mtDNA molecules which comprise a part of the electron chain transport. Accumulation of this mutant mtDNA was associated with mt functional decline, elevated ROS generation and increased oxidative damage at the cellular levels (Cortopassi & Wang, Reference Cortopassi and Wang1995; Lu et al. Reference Lu, Lee, Fahn and Wei1999).

Conditions of insufficient folate have been reported to cause disruption of mt homeostasis. Mt degeneration was found in the cerebrocortical microvascular wall of the brain of folate-deprived rats (Kim et al. Reference Kim, Lee and Chang2002). Ho et al. (Reference Ho, Ashline and Dhitavat2003) noticed an increase of depolarized mitochondria in cortical neuron resulting from folate deprivation. Folate may protect against the accumulation of the mtDNA4834 deletion in liver of chemotherapeutic drug-treated rats (Branda et al. Reference Branda, Brooks, Chen, Naud and Nicklas2002) and ageing rats (Crott et al. Reference Crott, Choi, Branda and Mason2005). However, it is currently not known whether mt abnormalities elicited by folate deficiency are associated with increased oxidative stress and if folate could act as an antioxidant to protect against oxidative stress-related mt decay as well as superoxide overproduction. The objective of the present study was to investigate the link underlying these relationships. Using the in vivo animal model, oxidative markers of mt decay including antioxidant defences, lipid and protein oxidative damage, mtDNA4834 deletion and respiratory electron chain activity were assessed in the liver of rats fed with folate-deficient (FD) or folate-replete (control) diets. An ex vivo model of primary hepatocytes isolated from FD and control rats was established to study mt dysfunction and superoxide overproduction in folic acid-supplemented and pro-oxidant-challenged conditions.

Materials and methods

Animals and experimental diets

A specially formulated l-amino acid-defined FD diet with 1 % succinylsulphothiazole was specially formulated by Harlan Teklad (Madison, WI, USA). The basal FD diet supplemented with 8 mg folic acid/kg was designated as the control diet (Walzem & Clifford, Reference Walzem and Clifford1988; Huang et al. Reference Huang, Hsu, Lin and Yang2001). The experimental protocols were approved by the Institutional Animal Care Committee of Fu-Jen University. Male weanling Wistar rats (n 60) were randomly assigned to the FD or control diet using a pair-fed model as previously described by Huang et al. (Reference Huang, Hsu, Lin and Yang2001). Twelve animals (n 6 for the FD and control group) were used for each of the following measured parameters: antioxidant assay, DNA deletion assay, cytochrome c oxidase (CcOX) staining assay, ROS and mt membrane potential assay. After a 4-week period, the rats were killed to collect tissues, or primary hepatocytes were isolated for further analysis.

Primary hepatocyte isolation

Primary hepatocytes were isolated by using a two-stage collagenase perfusion technique according to Lii & Hendrich (Reference Lii and Hendrich1993). Primary hepatocytes were cultured in collagen-coated plates and maintained in FD RPMI-1640 medium supplemented with 10 % heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum, antibiotics (2000 U/l penicillin, 20 mg/l streptomycin, 100 mg/l fungizone), 5 mg/l transferrin, 5 mg/ml insulin and various levels of folic acid. The normal culture medium contained 1·5 (sd 0·4) μm-folate as determined by the Lactobacillus casei method (Horne & Patterson, Reference Horne and Patterson1988). The cell culture was incubated in a CO2 incubator at 37°C.

Preparation of folic acid stock solution

A stock solution (10 mmol/l) of folic acid (pteroylmonoglutamic acid) was prepared by dissolving 44 mg folic acid in 10 ml NaHCO3 (10 g/l) solution. To make up media with various levels of folate, folate stock was added to FD medium and the pH was adjusted to 7·4. The stock solution was freshly prepared before performing each experiment.

Preparation of mitochondrial fraction

Rat liver mitochondria were isolated by conventional differential centrifugation in a STE buffer containing 250 mmol/l sucrose, 5 mmol/l Tris-HCl (pH 7·4) and 1 mmol/l EGTA (Johnson & Lardy, Reference Johnson and Lardy1967). Briefly, liver homogenates were prepared with the STE buffer by using a Potter-Elvehjem-type homogenizer. The homogenate was centrifuged twice at 1000 g at 4 °C and the mitochondria were then pelleted by centrifugation at 10 000 g for 30 min. The purity was determined by measuring the relative specific activities of glutamate dehydrogenase and lactate dehydrogenase in the supernatant and the mt pellet (Evans, Reference Evans and Rickwood1992). Yields of mt fractions, as reflected by their protein content (Bradford, Reference Bradford1976), were similar in various experimental groups.

Analysis of mitochondrial antioxidant status and oxidative insults

Folate levels were assessed using a microbiological assay performed by cryoprotected Lactobacillus casei in ninety-six-well microtitre plates (Horne & Patterson, Reference Horne and Patterson1988). The levels of mt reduced glutathione (Hissin & Hilf, Reference Hissin and Hilf1976), Mn–superoxide dismutase (Marklund & Marklund, Reference Marklund and Marklund1974) and glutathione peroxidase (Tappel, Reference Tappel1977) were determined according to the methods as previously described. Lipid peroxidation was quantified by measuring the production of thiobarbituric acid-reactive substances (Fraga et al. Reference Fraga, Leibovitz and Tappel1988). Protein carbonyl contents in mitochondria were evaluated as described by Reznick & Packer (Reference Reznick and Packer1994).

Analysis of the mitochondrial DNA4834 deletion

Total rat liver DNA was extracted (Huang et al. Reference Huang, Yaong, Chen and Lu2004), and the specific primers for the mtDNA4834 deletion were adapted from the report of Branda et al. (Reference Branda, Brooks, Chen, Naud and Nicklas2002). The thermal profile for amplification of the mtDNA4834 deletion was initiated with a 10 min denaturation period at 95 °C, followed by forty cycles of 95 °C for 15 s, 60 °C for 60 s and 72 °C for 60 s. The profile was completed within a 10 min period at 72 °C. All reactions were carried out in a GeneAmp DNA thermal cycler (Perkin Elmer, Wellesley, MA, USA). The amplified DNA fragments were separated by electrophoresis on a 2 % agarose gel at 100 V for 40 min.

Semi-quantification of deleted mitochondrial DNA heteroplasmy

To confirm and further analyse the heteroplasmy of the mtDNA deletion, we designed primers targeting a mtDNA region within the ND1 gene that is rarely deleted (forward primers: 5′-GTCTCAGGCTTTAACGTCG-3′; reverse primer: 5′-GGTCATATCGAAAACGGGG-3′), and a region of the CcOX subunit III gene that is deleted in the 4834 bp deletion (forward primer: 5′-TTCCAGCCTAGTTCCTACC-3′; reverse primer: 5′-GTGTCAGTATCATGCTGCG-3′), producing amplicons of 229 and 418 bp, respectively. Amplification of the ND1 and CcOXIII primers was initiated with a 60 s denaturation period at 94 °C, followed by thirty-two cycles of 95 °C for 60 s, 54 °C for 60 s and 72 °C for 60 s. This profile was completed within a 10 min period at 72 °C. To semi-quantify the relative amount of mtDNA4834 deletion, total DNA extracted from each of the liver samples was serially diluted between 20- and 223-fold with distilled water. The proportion of deleted CcOXIII to wild-type mtDNA, i.e. the deleted mtDNA heteroplasmy, was determined by the percentage of the highest dilution that caused the PCR product amplified from COXIII to be visible on the gel to that which caused the PCR product from total mtDNA (ND1) to be visible under identical conditions (Lee et al. Reference Lee, Pang, Hsu and Wei1994).

Analysis of respiratory complexes activity

According to the methods of Trounce et al. (Reference Trounce, Kim, Jun and Wallace1996), the activity of oxidative phosphorylation enzyme complexes was assayed by using mt protein extracted from rat livers. NADH–cytochrome c oxidoreductase was measured by the complex I+III coupled assay with NADH-dependent reduction of cytochrome c at 550 minus 540 nm (extinction coefficient: 19·0 mm− 1 cm− 1). Succinate–cytochrome c oxidoreductase was assayed via the reduction of cytochrome c by complex III coupled to succinate oxidation through complex II at 550 minus 540 nm. CcOX activity (complex IV) was measured by following the oxidation of reduced cytochrome c at 550 nm by using an extinction coefficient of ɛ550 = 27·7 mm− 1 cm− 1. Cytochrome c was reduced by l-ascorbate, purified by using a Sephadex G-25 column (Pharmacia Biotech, Piscataway, NJ, USA) and checked for full reduction by measuring absorbance at 550 and 565 nm. Histochemical reaction of CcOX was performed according to the method described by Seligman et al. (Reference Seligman, Karnovsky, Wasserkrug and Hanker1968) in which CcOX activity was assessed by 3,3′-diaminobenzidein staining after reducing cytochrome c.

Analysis of mitochondrial membrane potential and reactive oxygen species production

Mt membrane potential was quantified by rhodamine 123 staining and flow cytometric analysis as described in detail elsewhere (Huang et al. Reference Huang, Yaong, Chen and Lu2004). Intracellular ROS were assayed using the fluorescent dyes of dihydroethidine for superoxide anion and 2′,7′-dichlorofluorescein diacetate for other general ROS (Huang et al. Reference Huang, Yaong, Chen and Lu2004), and analysed using a flow cytometer (Coulter Corporation, Miami, FL, USA).

Statistical analyses

Data are presented as means and standard deviations. Effects of dietary folate intake on hepatic mtDNA mutation, function and oxidative injury were analysed by Student's t test or by one-way ANOVA with Duncan's multiple range tests using the General Linear Model of SAS (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA). Differences were considered significant at P < 0·05. The Pearson correlation coefficients were used to measure the association among supplemental folate levels, mt lipid and protein oxidative injury variables under pro-oxidant-treated conditions.

Results

Mitochondrial antioxidant status and oxidative injuries in rat liver during folate deprivation

After a 4-week dietary folate deprivation, plasma folate levels of FD rats were significantly lower than those of control rats (72 (sd 23) v. 113 (sd 7) ng/ml; P < 0·05), confirming the depleted folate status in FD rats. Table 1 shows the changes in the mt antioxidant defence system and oxidative injuries during folate deficiency. Compared with the controls, the Mn–superoxide dismutase activity and the reduced glutathione levels remained relatively unchanged, and the mt glutathione peroxidase activity significantly decreased in rat liver after a 4-week FD feeding period (P = 0·0333). In particular, 4-week folate deprivation remarkably decreased mt folate levels by 77 % as compared to the control values (P < 0·001). The mt thiobarbituric acid-reactive substances production was not different between FD and control livers. In contrast, folate deprivation significantly increased the mt contents of protein carbonyls in rat liver (P = 0·0278).

Table 1 Effects of folate deprivation on mitochondrial (mt) antioxidant status and oxidative injuries in rat liver (n 6)† (Mean values and standard deviations)

FD, folate-deficient; GPX, Se–glutathione peroxidase; GSH, reduced glutathione; Mn–SOD, Mn–superoxide dismutase; TBARS, thiobarbituric acid-reactive substances.

Mean values were significantly different from those of the control group: *P < 0·05.

† Wistar rats were fed with the FD or control diet for 4 weeks and liver mitochondria were isolated. For details of procedures, see Materials and Methods.

‡ Measured as malondialdehyde equivalents.

Detection of mitochondrial DNA4834 deletion and heteroplasmy in folate-deficient rat liver

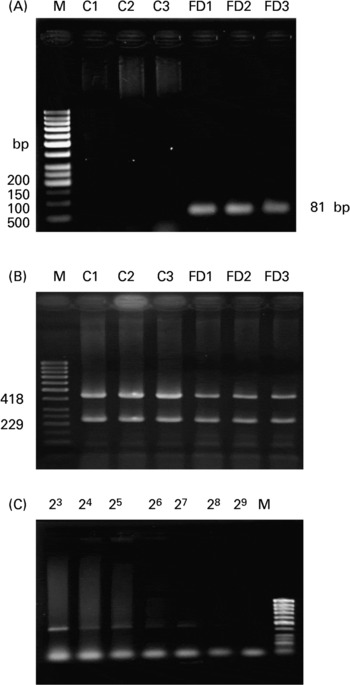

As shown in the representative agarose image in Fig. 1(A), the mtDNA4834 deletion was detected as an 81 bp PCR product in the FD (lanes 4–6) but not in the controls (lanes 1–3). In Fig. 1(B), there was a decrease in the intensity of 418 bp PCR product (deleted mtDNA: CcOXIII) in FD rat livers compared with the controls, while 229 bp PCR product (wild-type mtDNA: ND1) was amplified similarly in both the groups. By normalizing with ND1 intensity, the relative ratio of CcOXIII to ND1 was 1·11 (sd 0·12) for the controls and 0·84 (sd 0·09) for the FD group (six rats in each group; P = 0·0312). The data confirmed the deletion of mtDNA in FD rat liver to result in CcOXIII gene loss. Using a serial dilution PCR method, the highest dilution that caused the PCR product amplified from CcOXIII to be visible on the gel was 28 (Fig. 1(C)) and 211 for ND1 (data not shown) in FD rat liver. The deleted mtDNA heteroplamy was calculated as the ratio of dilution-fold in CcOXIII/ND1 from six FD rats, i.e. 0·104 (sd 0·035) %.

Fig. 1 Analysis of the 4834 bp large deletion in mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA4834 deletion) in rat liver. (A), The representative agarose image for the mtDNA4834 deletion in livers of three rats fed with the control (C) or folate-deficient (FD) diet for 4 weeks. Total DNA was extracted and the mtDNA4834 deletion was detected using the PCR technique described in the Materials and Methods. PCR amplification of the 4834 bp deleted mtDNA sequence resulted in an 81 bp product. (B), Representative autoradiogram of the heteroplasmy of the mtDNA deletion in the liver of one rat fed with the control (C) or FD diet for 4 weeks. The gel image distinguishes between mtDNA outside the deletion region (229 bp) and the CcOXIII gene within the deletion region (418 bp) on the basis of size. Lane M contains a molecular weight marker. Each lane refers to a sample from a FD and a pair-fed control rat liver. (C), Representative autoradiogram showing the proportion of the CcOXIII gene relative to the ND1 gene in FD rat liver after serial dilution PCR analysis. Total DNA extracted from each of the liver samples was serially diluted between 20- and 223-fold with distilled water.

Respiratory chain activity in mitochondria of control and folate-deficient rat liver

In order to determine if increased oxidative insults in mitochondria of FD rat liver were associated with mt dysfunction on the respiratory chain, the activities of the complex I–IV were measured. Table 2 demonstrates that only trace glutamate dehydrogenase specific activity (mt matrix maker enzyme) was detectable in cytosol, indicating that mitochondria are intact during the isolation procedure. Activities of NADH–cytochrome c oxidoreductase (complex I+ III) and succinate–cytochrome c oxidoreductase (complex II + III) did not differ between control and FD rat mitochondria. CcOX (respiratory complex IV) activity in FD liver mitochondria was significantly reduced by 30 % when compared to that in the controls (P = 0·0264).

Table 2 Effect of folate deprivation on activities of liver mitochondrial respiratory complexes (n 6)† (Mean values and standard deviations)

CcOX, cytochrome c oxidase; FD, folate-deficient; NCCR, NADH–cytochrome-c oxidoreductase; SCCR, succinate–cytochrome c oxidoreductase.

Mean values were significantly different from those of the control group: *P < 0·05.

† Wistar rats were fed with the FD or control diet for 4 weeks and liver mitochondria were isolated and enzymatic activities were assayed. For details of procedures, see Materials and Methods.

‡ Specific enzyme activity of glutamate dehydrogenase, a mitochondrial marker enzyme.

Supplemental folic acid modulated cytochrome c oxidase activity in the absence/presence of pro-oxidant challenge

The decreased CcOX activity in FD rat liver was confirmed by histochemical analysis on primary hepatocytes isolated from FD and control rats (Fig. 2(A, B)). The circled hepatocytes represent the cells with reduced CcOX activity. Additional pro-oxidant challenge (32 μmol/l CuSO4 treatment for 48 h) further decreased CcOX activity in both FD and control hepatocytes (Fig. 2(C, D)). Preincubation of FD and control hepatocytes with 100 and 1000 μmol/l folic acid for 4 h before oxidant treatment restored CcOX activity (Fig. 2(E–H)).

Fig. 2 Supplemental folic acid-modulated cytochrome c oxidase (CcOX) activity in the absence/presence of pro-oxidant challenge. Primary hepatocytes isolated from rats fed folate-deficient (FD; A, C, E, G) or control (B, D, F, H) diets were cultured in FD or complete RPMI medium, respectively. FD and control hepatocytes were preincubated with supplemental folic acid at levels of 0 (A–D), 100 μm (E, F) and 1000 μm (G, H) for 4 h, treated with pro-oxidant (32 μm-copper sulphate) for 48 h (C–H), and then were harvested for histochemical assay of CcOX activity as described in the Materials and Methods. Hepatocytes in the circular markers represent the cells with reduced CcOX activity.

Supplemental folic acid modulated mitochondrial membrane potential in the absence/presence of exogenous pro-oxidant challenge

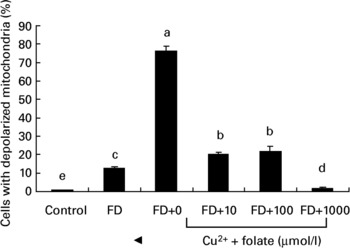

To investigate if the altered activity of CcOX in FD hepatocytes was associated with membrane dysfunction, mt depolarization was analysed. Fig. 3 shows that FD hepatocytes with defective CcOX function had a significantly higher percentage of depolarized mitochondria than the controls. Pro-oxidant treatment of FD hepatocytes (32 μmol/l CuSO4 for 48 h) aggravated mt depolarization, as revealed by a 6-fold increase in depolarized cell fractions compared with the untreated FD hepatocytes. Supplemental folic acid at 100–1000 μmol/l significantly alleviated pro-oxidant-induced mt depolarization.

Fig. 3 Supplemental folic acid-modulated mitochondrial membrane potential in the absence/presence of pro-oxidant challenge. Culture conditions and CuSO4 treatment are as described in Fig. 2. The uptake of R123 was analysed by flow cytometry. Values are means with their standard deviations depicted by vertical bars (n 6). a–e Mean values with unlike letters were significantly different (P < 0·05). FD, folate-deficient.

Supplemental folic acid reduced superoxide, but not general reactive oxygen species, production in the absence/presence of exogenous pro-oxidant challenge

Both CcOX inhibition and mt membrane depolarization are known to produce ROS generation. Changes of intracellular ROS in general or superoxide in particular in the control and FD hepatocytes were simultaneously measured. As shown in Fig. 4, FD hepatocytes with dysfunctional mitochondria had a significantly higher level of intracellular dihydroethidine intensity (superoxide anions) than controls, whereas intracellular 2′,7′-dichlorofluorescein diacetate intensity (mainly label of general ROS such as hydrogen peroxide) did not differ in either of the groups (Fig. 4(A, B)). Upon pro-oxidant treatment (32 μmol/l CuSO4) for 48 h, both dihydroethidine and 2′,7′-dichlorofluorescein diacetate intensity of FD hepatocytes were significantly elevated with increase in the former (3·5-fold) being greater than the latter (1·5-fold). Preincubation of FD hepatocytes with 10–1000 μmol/l folic acid for 4 h significantly reduced intracellular dihydroethidine fluorescent intensity levels in a dose-dependent manner, with no effect on the reduction of 2′,7′-dichlorofluorescein diacetate levels.

Fig. 4 Supplemental folic acid affected reactive oxygen species (ROS) production in the absence/presence of exogenous pro-oxidant challenge. Culture conditions and CuSO4 treatment are as described in Fig. 2. Intracellular superoxide and general ROS production in hepatocyte cultures were measured by dihydroethidine (HE) and 2′,7′-dichlorofluorescein diacetate (DCF) fluorescence, respectively, and analysed by flow cytometry. Values are means with their standard deviations depicted by vertical bars (n 6). a–f Mean values with unlike superscript letters were significantly different (P < 0·05). FD, folate-deficient.

Supplemental folic acid protected pro-oxidant-challenged mitochondria from oxidative injuries

We continued to assess whether supplemental folic acid has direct antioxidant protection against pro-oxidant-elicited oxidative injuries in mitochondria. As shown in Table 3, pro-oxidant treatment elicited less mt protein and lipid oxidative injury in controls compared with the FD group. Supplemental folic acid protected pro-oxidant-challenged liver mitochondria of both control and FD rats from protein and lipid peroxidation. There were strong and significant inverse correlations among supplemental folic acid levels and pro-oxidant-elicited mt oxidative injuries in both FD and control rat liver.

Table 3 Effects of supplemental folic acid on protein carbonyl content and thiobarbituric acid-reactive substances (TBARS) levels in folate-deficient (FD) and control rat liver mitochondria under pro-oxidant stimulation (n 6)† (Mean values and standard deviations)

a,b,c Mean values for the respective parameter within a column with unlike superscript letters were significantly different (P < 0·05; two-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett's test).

x,y Mean values within a row with unlike superscript letters were significantly different (P < 0·05; two-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett's test).

† Wistar rats were fed with the FD or control diet for 4 weeks and liver mitochondria were isolated. Aliquots of mitochondrial fraction were incubated at 37°C with Tris buffer in the presence/absence of 50 mmol FeSO4/l as well as with supplemental folic acid at the levels of 0–10 mm for 1 h. For details of procedures, see Materials and Methods.

‡ Measured as malondialdehyde equivalents.

§ Pearson correlation coefficients were used to measure the association between mt oxidative injuries and supplemental folic acid levels.

Discussion

The present study identified a previously unrecognized biological effect of folate in the protection of mitochondria against oxidative insults. The evidence of increased mt protein carbonyls and accumulated mtDNA4834 deletion indicate an elevated oxidative stress inside the liver mitochondria during folate deprivation (Table 1; Fig. 1). Only some measure of mt antioxidant defences (glutathione peroxidase activity) was altered with no obvious changes in the other markers (reduced glutathione and Mn–superoxide dismutase), suggesting that the 4-week dietary folate deprivation promoted a moderate rather than an acute oxidative stress in liver mitochondria. Consistently, modest changes of oxidative measures with no altered reduced glutathione, vitamin E contents and catalase activity were found in rat liver homogenate after a 4-week folate depletion (Huang et al. Reference Huang, Hsu, Lin and Yang2001). The molecular basis behind this increased oxidative stress in folate-depleted mitochondria is not established. It may be partially due to a drastic drop of mt folate level in particular (Table 1). Reduced folate such as tetrahydrofolate and 5-methyltetrahydrofolate has been known for its antioxidant ability to scavenge free radicals in vitro (Rezk et al. Reference Rezk, Haenen, van der Vijgh and Bast2003) and to alleviate oxidative stress in vivo (Doshi et al. Reference Doshi, McDowell and Moat2001; Coppola et al. Reference Coppola, D'Angelo and Fermo2005). Alternatively, folate was reported to interact with nitric oxide synthase, improve quinonoid BH4 availability and reduce superoxide production (Stroes et al. Reference Stroes, van Faassen and Yo2000; Doshi et al. Reference Doshi, McDowell and Moat2001). This elevated oxidative stress in folate-depleted mitochondria may also be critical in the accumulation of mtDNA large deletion (Fig. 1). The occurrence of this common mtDNA deletion has been correlated with increased oxidative damage of increased 8-hydroxydeoxyguanosine (8-OHdG) levels (Lezza et al. Reference Lezza, Mecocci, Cormio, Beal, Cherubini, Cantatore, Senin and Gadaleta1999), which may cause strand breakage and recombination between homologous sequence flanking deletion site. Taken together, the present data not only confirm that folate insufficiency disrupted mt homeostasis but also reconcile the previous reports of folate deprivation-associated mt decay (Branda et al. Reference Branda, Brooks, Chen, Naud and Nicklas2002; Kim et al. Reference Kim, Lee and Chang2002; Ho et al. Reference Ho, Ashline and Dhitavat2003; Crott et al. Reference Crott, Choi, Branda and Mason2005) with its antioxidant action.

The most striking finding of the present study was the specific impact of folate deficit on respiratory complex IV activity. Dietary folate restriction led to the 30 % reduction of CcOX activity in rat liver mitochondria, whereas other respiratory chain activities of complex I, II and III were not affected (Table 2). The reduced CcOX activity in FD hepatocytes or in pro-oxidant-treated hepatocytes can be restored by supplemental folic acid (Fig. 2). To our knowledge, this is the first in vivo evidence indicating that folate status could modulate CcOX activity, confirming the finding in the in vitro study by Brookes & Baggott (Reference Brookes and Baggott2002) to identify complex IV as the site of electron donation by 10-formyl-tetrahydrofolate in isolated rat liver mitochondria. The molecular mechanisms by which folate modulates CcOX activity, however, remain largely unknown. Several possible regulations are plausible. (1) Since FD-induced mtDNA large deletions result in a loss of the CcOXIII gene (Fig. 1(B)), one may speculate that this decreased copy number of the CcOXIII gene in FD tissues may cause an impaired CcOX protein leading to CcOX dysfunction. This postulation is supported by the fact that large-scale deletions of mtDNA have been associated with CcOX dysfunction in human mt disorders and the ageing process (Schon et al. Reference Schon, Bonilla and Dimauro1997). (2) The decline of CcOX activity can be attributed to a specific alteration in the mt cardiolipin content, probably due to a peroxidative attack of the phospholipids by mt ROS (Paradies et al. Reference Paradies, Petrosillo, Pistolese and Ruggiero2000). The antioxidant properties of folate in mitochondria, as previously demonstrated, highly support this possibility. Indeed, the reduced CcOX activity in pro-oxidant-treated hepatocytes correlated with increased lipid peroxidation in liver mitochondria, both of which were reversible by supplemental folic acid (Fig. 2; Table 3). (3) It cannot be excluded that mutations in genes of CcOX subunits may contribute to CcOX dysfunction of FD rat liver. Gene mutations in CcOX I–III subunits (Hoffbuhr et al. Reference Hoffbuhr, Davidson and Filiano2000; D'Aurelio et al. Reference D'Aurelio, Pallotti and Barrientos2001) as well as CcOX assembly factors (Sue et al. Reference Sue, Karadimas and Checcarelli2000) have been associated with CcOX dysfunction. Folate deficiency has been known to increase chromosomal instability and promote genetic mutations (Duthie et al. Reference Duthie, Narayanan, Brand, Pirie and Grant2002). Further studies are warranted to elucidate the genetic and epigenetic mechanisms of folate in the regulation of CcOX function.

The impaired CcOX protein function by chemicals, pro-oxidants or by hypoxia has been shown to cause an accumulation and leakage of electrons from the early complexes, disturbed mt membrane potential and increased superoxide production (Ksenzenko et al. Reference Ksenzenko, Konstantinov, Khomutov, Tikhonov and Ruuge1983; Hagen et al. Reference Hagen, Yowe, Bartholomew, Wehr, Do, Park and Ames1997; Duranteau et al. Reference Duranteau, Chandel, Kulioz, Shao and Schumacher1998; Paradies et al. Reference Paradies, Petrosillo, Pistolese and Ruggiero2000; Palacios-Callender et al. Reference Palacios-Callender, Quintero, Hollis, Springett and Moncada2004). Consistently, FD hepatocytes with CcOX deficit displayed mt membrane depolarization and a concomitant increase of intracellular superoxide levels (Figs. 2–4). The reduced CcOX activity in pro-oxidant-treated FD hepatocytes was reversible by supplemental folate, which coincided with a normalized mt membrane potential as well as a corresponding decrease of intracellular superoxide levels. Thus, the evidence suggests that superoxide scavenging capability of folate observed in both the present and other studies (Doshi et al. Reference Doshi, McDowell and Moat2001; Huang et al. Reference Huang, Huang, Lin, Hung and Lu2002, Reference Huang, Yaong, Chen and Lu2004) may be in part mediated through modulating mt CcOX and membrane function.

It should be noted that the supplemental folate used in the present study to protect liver mt against endogenous or pro-oxidant-induced oxidative injuries was folic acid. Folic acid is not a natural substance and therefore may not be taken up by cells and cross the mt membrane. Presumably, the added folic acid in animal diets or in folic acid-supplemented medium must be metabolized to natural forms of reduced folate by dihydrofolate reductase in order to cross the mt membrane. Indeed, our in vivo and ex vivo data suggest that folic acid is biologically active to protect mitochondria from oxidative injuries. On the other hand, the effective dose of folic acid to counteract mt oxidative injuries in the present study was found at micromolar levels, which are much greater than those encountered in the human physiological system (nanomolar levels). One will raise the question whether effects of folic acid found in the present study have physiological relevance. Future studies are warranted to investigate the influence of physiologically relevant reduced folate metabolites and concentrations on mt function.

In conclusion, the present findings identify an antioxidant action of folic acid to protect against mt oxidative injuries, CcOX dysfunction and membrane depolarization. Supplemental folic acid attenuates the oxidative defects in mitochondria of pro-oxidant-treated hepatocytes. Implication of increased folic acid levels as a possible determinant of mt function may unveil a new potential target to reduce intracellular superoxide overproduction. The question as to whether folic acid supplementation may present an effective dietary strategy to help improve oxidative stress-related mitochondria disorders or ageing-associated conditions in man, however, requires further study.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge Prof. C. K. Lii (Department of Nutritional Sciences, Chung Shan Medical University) for guidance in the techniques of primary hepatocyte isolation. The authors are deeply grateful to Prof. Y.-H. Wei in the Department of Biochemistry at the National Yang-Ming University for the kind support and invaluable advice on mitochondrial DNA mutations. We thank Dr Y.-A. Lee in the Department of Life Science and Dr J. F. Lu in the Department of Medicine for helpful discussion of primer design and mitochondrial extraction. Dr B. Stephen Inbaraj's efforts in the English editing of this manuscript is appreciated. This study was supported by grants from the National Science Council, Taiwan (NSC 91-2320-B-030-002, NSC94, 95-2320-B-030-002 to R. F. S. Huang).