Alzheimer’s disease aetiology and treatments

Neurodegenerative diseases of ageing are a cluster of conditions characterised by deteriorating brain function associated with the gradual and regionally selective loss of brain cells that have become a major concern for society(Reference Gaskin, Gomes and Darshan1). The most common neurodegenerative disease of ageing is Alzheimer’s disease (AD), a chronic syndrome in which progressive cognitive decline ultimately threatens the individuals’ capacity to reason clearly and perform basic activities of daily living(Reference Kumar and Singh2). Despite the broad documentation of multiple factors affecting the development of AD pathogenesis, the exact aetiology underlying AD remains unclear(Reference Reitz, Brayne and Mayeux3,Reference Gatz, Reynolds and Fratiglioni4) . Normal ageing is accompanied by some decrease in certain cognitive abilities, but a large proportion of the population remains cognitively healthy during their lifetime, indicating that advanced cognitive dysfunction is not an inevitable consequence of old age(Reference Ardila, Ostrosky-Solis and Rosselli5). Thus, the progression of brain neuropathology leading to AD is not related to ageing per se, but to environmental and genetic factors(Reference Nelson, Head and Schmitt6). To date, the quest for disease-modifying therapies addressing the amyloid, tau and neurotransmitters hypotheses(Reference Kametani and Hasegawa7) has failed to produce an approved drug in over 20 years, highlighting the difficulty in determining the right target, type of intervention and/or timing to intervene(Reference Sperling, Jack and Aisen8). At present, only two neurotransmitter-based therapies – cholinesterase inhibitors and an N-methyl-D-aspartate antagonist – have been approved for the management of cognitive symptoms, but they remain ineffective for reversing underlying AD pathology(Reference Parsons, Danysz and Dekundy9).

Over the last decade, considerable interest has emerged in the role of brain energy metabolism in the natural history of AD-related cognitive decline(Reference Cunnane, Nugent and Roy10). Long considered as a simple biomarker of neuronal death in the progression and manifestation of clinical symptoms of AD, altered brain glucose utilisation is now believed to have more of a causal or aggravating role in the development of AD(Reference Kuehn11). Furthermore, regional brain glucose hypometabolism (BGH) assessed by positron emission tomography (PET) with 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) is a reliable marker to predict the conversion from cognitively normal adults to mild cognitive impairment (MCI) and MCI to AD(Reference Sörensen, Blazhenets and Rücker12,Reference Mosconi, De Santi and Li13) . Longitudinal studies in late-onset (sporadic) and autosomal dominant AD have demonstrated that regional BGH may develop secondarily to amyloid plaque deposition, but it can also develop prior to the neuropathology in at least a quarter of sporadic AD(Reference Jack, Wiste and Weigand14–Reference Gordon, Blazey and Su18). The pattern of regional cerebral amyloid deposition was previously reported to not be correlated with brain glucose BGH(Reference Altmann, Ng and Landau19,Reference Edison, Archer and Hinz20) , but recent studies challenged these findings by reporting positive associations with amyloid and local or distant AD-related brain regions displaying hypometabolism(Reference Bischof, Jessen and Fliessbach21,Reference Pascoal, Mathotaarachchi and Kang22) . Regardless of whether impairment in energy metabolism constitutes a primary or secondary event in AD, it is of great interest to better understand its role in the onset of the disease and determine whether correcting it could be an effective treatment or preventive strategy. AD pathologies can be present over 20 years before the onset of clinical symptoms(Reference Vermunt, Sikkes and Van Den Hout23) which offers a critical window of opportunity to initiate treatments and hopefully change the course of the disease after which reversing neurological damage and functional decline might prove to be more difficult(Reference Emery24).

Lifestyle improvement including dietary modifications is recommended as the first-line treatment for most chronic diseases. Observational studies show that increased consumption of single nutrient classes (n-3(Reference Fotuhi, Mohassel and Yaffe25), antioxidants(Reference Mecocci and Polidori26)), certain food groups (vegetables(Reference Loef and Walach27), fish(Reference Morris, Evans and Tangney28)) as well as energetic restriction(Reference Van Cauwenberghe, Vandendriessche and Libert29) offer some protection against AD, but results from adequately powered randomised controlled trials (RCT) in humans have yielded mixed results or are simply lacking(Reference Aisen, Schneider and Sano30,Reference Quinn, Raman and Thomas31) . In healthy adults(Reference Solfrizzi, Custodero and Lozupone32) and adults with MCI(Reference Scarmeas, Stern and Mayeux33), adherence to nutrient-rich dietary patterns (Mediterranean, Dietary approaches to stop hypertension (DASH), Mediterranean-DASH intervention for neurodegenerative delay (MIND)) has been shown to improve cognitive function and reduce the risk of AD but, again, most of these findings are based on epidemiological studies and do not establish a causal relationship. Diets with high glycaemic load and sugar content are associated with increased levels of cerebral amyloid and lower global cognitive performance, respectively, in older adults, potentially highlighting a link between diet composition and brain health(Reference Taylor, Sullivan and Swerdlow34). At the other end of the dietary spectrum, very-low-carbohydrate ketogenic diets (KD), which have a marked effect on brain energy metabolism(Reference Courchesne-Loyer, Croteau and Castellano35), have yielded encouraging preliminary results in populations with cognitive deficits(Reference Grammatikopoulou, Goulis and Gkiouras36).

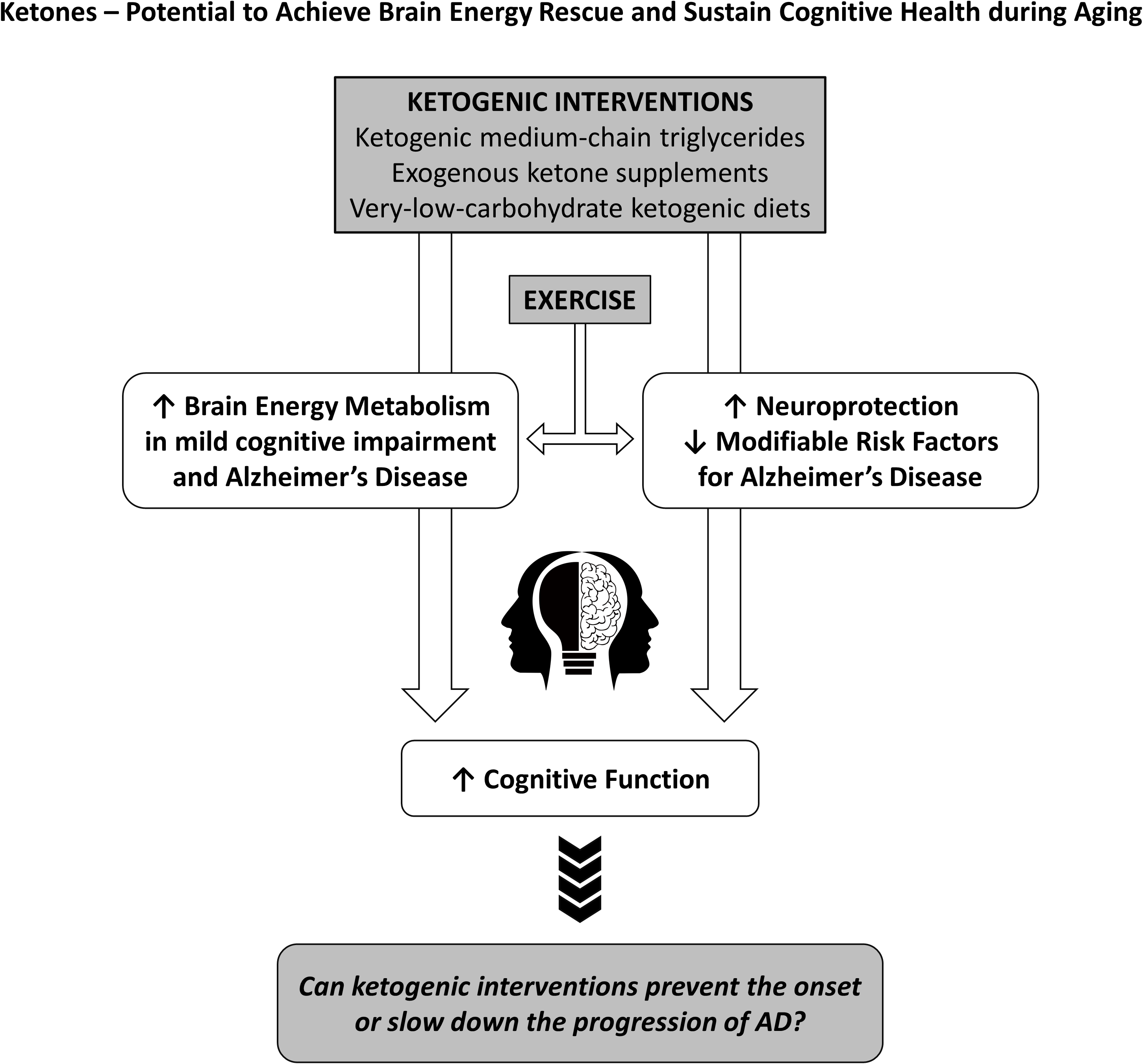

Since the brain possesses very limited glycogen storage capacity, sufficient and continuous substrate and oxygen delivery from the periphery is critical to ensure optimal brain health and resilience throughout the lifespan. Under normal circumstances, glucose is the main fuel for the brain and accesses the intracellular space via specific glucose transporters GLUT-1 and GLUT-3, and to a lesser extent insulin-stimulated GLUT-4(Reference Duelli and Kuschinsky37). When glucose availability is severely limited for a prolonged period such as during fasting or a KD, the ketones – acetoacetate (AcAc) and β-hydroxybutyrate (βHB) – are synthesised by the liver at an increased rate and contribute significantly to the energetic demands of the brain(Reference Owen38). The recent advent of exogenous ketones now allows individuals to similarly increase circulating ketones without having to make dietary changes. In this review, we will present evidence supporting the use of ketogenic interventions as a principal component of ‘brain energy rescue’ strategies to bypass BGH, maintain brain fuel supply and improve cognitive health during ageing(Reference Cunnane, Trushina and Morland39).

Regional brain glucose hypometabolism in individuals with or at risk of Alzheimer’s disease

Starting in 1963, a series of arteriovenous difference studies were conducted in individuals at different stages of AD and reported significant reductions of 22–55 % in global brain glucose utilisation as compared with age-matched controls(Reference Dastur, Lane and Hansen40–Reference Lying-Tunell, Lindblad and Malmlund44), whereas cerebral blood flow and oxygen consumption were far less impaired(Reference Ogawa, Fukuyama and Ouchi42,Reference Hoyer, Oesterreich and Wagner43) . Using PET with the glucose tracer 18FDG, BGH has been widely confirmed in AD on many occasions(Reference Benson, Kuhl and Hawkins45–Reference Croteau, Castellano and Fortier50). As with cognitive performance, the magnitude of the whole-brain decline in cerebral metabolic rate (CMR) of glucose worsens with advancing AD and is usually on the order of ∼10–20 % in mild AD, with specific regional deficits of 10–50 %. In AD, the regional pattern seems to affect initially the medial temporal lobe including the hippocampus as well as the parietal cortex, and posterior cingulate(Reference Croteau, Castellano and Fortier50,Reference Mosconi, Mistur and Switalski51) . Along these lines, accumulation in the posterior cingulate and precuneus regions of certain metabolites including glucose has been previously reported in AD and likely reflects their under-utilisation as an energy source(Reference Mullins, Reiter and Kapogiannis52).

MCI is a condition characterised by cognitive decline greater than what is expected during normal ageing but that does not yet interfere with activities of daily life. It is usually defined by a combination of: (i) subjective concern regarding a change in cognition, (ii) objective evidence of lower performance in one or more cognitive domains and (iii) preservation of independence in functional abilities in daily life(Reference Petersen53). Individuals with MCI, particularly the amnestic subtype which affects memory, are at higher risk of developing AD(Reference Fischer, Jungwirth and Zehetmayer54). In this population, regional BGH starts in the posterior cingulate cortex(Reference Ma, Sheng and Pan55), progresses to the temporal and parietal cortices and is considered to be a sensitive marker of AD risk and progression(Reference Ewers, Brendel and Rizk-Jackson56). Since 2000, several studies in MCI using PET-FDG have reported significant reductions in glucose utilisation of up to 20 % in AD-vulnerable brain regions(Reference Croteau, Castellano and Fortier50,Reference Li, Rinne and Mosconi57–Reference De Santi, de Leon and Rusinek60) . These findings suggest that MCI represents an intermediary state of metabolic decline in which BGH is more pronounced compared with healthy older adults but in which the decline is still lower in magnitude and spatial distribution than in AD. Recently, the longest PET-FDG study in MCI (median follow-up of 72 months) clearly demonstrated the progressive decline in glucose utilisation potentially leading to AD-onset and observed a significantly higher rate of decline in ApoE ϵ4 carriers as compared with non-carriers in several brain regions(Reference Paranjpe, Chen and Liu61). Taken together, these reports clearly indicate that BGH is already present in individuals with various levels of cognitive deficit, but they do not provide information as to the chronological sequence of cognitive, pathological and brain energetic impairment over time.

In cognitively healthy older people, mild BGH is observed almost exclusively in the frontal cortex(Reference Nugent, Castellano and Goffaux62). Hence, BGH changes qualitatively and quantitatively from normal ageing to MCI and AD; the qualitative change is in the brain regions affected, while the quantitative change is that the magnitude of BGH increases as objective signs of cognitive decline become apparent. Less decline in glucose utilisation in the anterior cingulate cortex and the anterior temporal lobes of older adults (80+ years old) has recently been associated with both cognitive resilience and vascular health and proposed as a disease-targeting, modifiable risk factor for AD(Reference Arenaza-Urquijo, Przybelski and Lesnick63). Hence, the cognitively healthy older person is an important reference to set the baseline for the energy deficit in MCI and AD but, equally, is also a target for brain energy modifying interventions aiming to reduce the risk of progression to MCI or AD.

For decades, BGH in AD was considered to result from advanced neuronal dysfunction, which correlates well with the degree of cognitive impairment(Reference Gómez-Isla, Price and McKeel64), but emerging evidence reporting its occurrence years prior to the onset of AD clinical symptoms challenges this interpretation(Reference Cunnane, Trushina and Morland39,Reference Mosconi, Pupi and De Leon65) . Indeed, populations at high risk for AD including the ones carrying genetic mutations presenilin-1(Reference Schöll, Almkvist and Bogdanovic66), young adults carrying the APOE 4 gene(Reference Reiman, Chen and Alexander67) or with a family history of AD(Reference Mosconi, Brys and Switalski68) display reduced regional PET-FDG uptake in the brain decades before the onset of the cognitive deficit. Individuals with risk factors for AD such as age > 65 years(Reference Nugent, Tremblay and Chen69), IR(Reference Baker, Cross and Minoshima70) and subjective memory complaints(Reference Mosconi, De Santi and Brys71) also present impairments in brain glucose utilisation. The reported reduction in regional brain glucose utilisation in these populations ranged from 8 to up to 25 % and, as in AD, affected the parietal cortex, posterior cingulate and temporal cortex. Clearly, BGH can develop pre-symptomatically so it is conceivable that it plays a contributing role in the development of brain energy deficit and AD-associated cognitive decline. This does not exclude the possibility that neuronal dysfunction and death further exacerbate BGH as part of a vicious cycle. BGH may not be the first detectable form of dysfunction in the ageing brain, but it has an upstream place in the cascade of events leading to AD.

Underlying mechanisms of impaired brain glucose utilisation

The disruption of glucose utilisation in the brain of individuals with cognitive decline is widely observed, but its underlying causes are still not fully understood. In AD, numerous abnormalities in brain glucose transport (e.g. cerebral perfusion, blood–brain barrier, cerebral blood flow and GLUT1 and GLUT3 expression) and metabolism (e.g. glycolysis, pentose phosphate pathway, tricarboxylic acid cycle, oxidative phosphorylation) have been reported(Reference Sweeney, Sagare and Zlokovic72–Reference Dai, Lopez and Carmichael76). Normally, brain glucose delivery largely exceeds local consumption thereby almost always avoiding a potential brain energy shortage(Reference Dienel77). Brain regions vulnerable to AD can display glucose accumulation, suggesting that glucose transport might not be the initial limiting factor in brain glucose utilisation(Reference An, Varma and Varma73).

In AD, mitochondrial dysfunction is part of a vicious cycle contributing to amyloid beta and tau pathology, both closely associated with oxidative damage which promotes further mitochondrial dysfunction, proteotoxicity, cell dysfunction and death(Reference Butterfield and Halliwell74,Reference Norwitz, Mota and Norwitz78) . Mitochondrial structure and function differ significantly between AD and healthy older adults including total number, protein expression, antioxidant capacity and enzymatic activity in the tricarboxylic acid cycle and oxidative phosphorylation complexes I, III and IV 96. Such pathological changes reduce ATP production from glucose by 20–50 % in sporadic AD(Reference Hoyer41). Thus, mitochondrial dysfunction is a major and early defect responsible for the reduction in brain glucose utilisation in AD(Reference Onyango, Dennis and Khan79). However, glycolysis is up-regulated during brain activation(Reference Dienel77) and glycolytic impairment in specific brain regions has also been proposed as a fundamental feature contributing to AD symptoms(Reference An, Varma and Varma73). In addition to limiting ATP production, dysregulation in glycolysis would also reduce the amount of anaplerotic intermediates entering the citric acid cycle which in turn would limit oxidative phosphorylation and the synthesis of acetylcholine and γ-aminobutyric acid.

In the brain, insulin’s role goes beyond glucose homoeostasis(Reference Hancock, Meyer and Mistry80) and impairment in its signalling pathways is now recognised as an important characteristic of AD(Reference De la Monte and Wands81). Brain insulin resistance (IR) can develop in the absence of systemic IR(Reference Arnold, Arvanitakis and Macauley-Rambach82), but epidemiological and neuroimaging studies consistently report a strong association between type 2 diabetes and AD, suggesting that both peripheral and central IR usually co-exist(Reference Su, Naderi and Samson83,Reference Willette, Bendlin and Starks84) . In patients with AD, impaired insulin action may contribute to abnormal brain energetics in several ways including impaired mitochondrial oxidative metabolism and ATP-dependent maintenance processes that are critical to neuronal survival(Reference Blonz85). Moreover, increased production of reactive species and inflammatory cytokines resulting from reduced brain insulin signalling damage brain cell structure and functional integrity(Reference Hoyer, Lee and Löffler86). It is also possible that IR down-regulates the utilisation of glucose through the blood–brain barrier and by altering GLUT4 trafficking, though the impact on overall brain glucose homoeostasis remains to be determined(Reference McNay and Pearson-Leary87). While it is unclear whether IR on its own is enough to cause neuronal damage, it can exacerbate (and be exacerbated by) the pathophysiological mechanisms underlying AD, particularly amyloid β accumulation (via the competitive inhibition of its degradation) or neuronal loss (via apoptosis)(Reference Norwitz, Mota and Norwitz78).

Brain ketone metabolism in health and Alzheimer’s disease

The common perception that glucose is the obligatory and preferred fuel for the brain originates from the observations that insulin-induced hypoglycaemia leads to severe sensory and cognitive disturbances that can be reversed by the administration of glucose(Reference Agardh, Folbergrovaa and Siesjou88) and that, under normal conditions, glucose is the dominant source of energy for the brain(Reference Owen, Morgan and Kemp89). However, βHB infusion and prolonged fasting attenuate the physiological response to severe hypoglycaemia including autonomic symptoms(Reference Veneman, Mitrakou and Mokan90–Reference Drenick, Alvarez and Tamasi92), neuronal death(Reference Julio-Amilpas, Montiel and Soto-Tinoco93) and cerebral energy metabolism(Reference Dardzinski, Smith and Towfighi94). Moreover, under circumstances in which the ketone:glucose ratio in the blood is increased allowing for potential substrate competition, brain glucose utilisation is displaced by ketones and its oxidation by the normal brain is reduced(Reference Courchesne-Loyer, Croteau and Castellano35). Generally, an increase of 0·1 mM in plasma βHB is usually paralleled by an increase of 1·0–1·2 % in the contribution of ketones to total brain energy metabolism(Reference Masino95). In extreme physiological ketosis (∼6–7 mM of βHB) such as a 30–40-d fast, ketones can become the major fuel of the brain and provide up to 2/3 of its total energy needs(Reference Owen, Morgan and Kemp89). Some evidence suggests that the ketone contribution to total brain energy metabolism does not surpass this 2/3 value even when βHB levels are as high as 8 mM in humans(Reference Drenick, Alvarez and Tamasi92) and 17 mM in rats(Reference Chowdhury, Jiang and Rothman96) unless a high level of insulin is infused simultaneously(Reference Drenick, Alvarez and Tamasi92). One possible explanation is that, like fatty acids, ketones ‘burn in the flame of carbohydrates’ and thus require the presence of an anaplerotic substrate like glucose to replenish tricarboxylic acid intermediates and ensure the complete oxidation of ketones to ATP(Reference Russell and Taegtmeyer97). Excessive ketone metabolism in the brain at the expense of glucose could potentially have a detrimental impact on neuronal signalling driven by glutamate(Reference Hertz, Chen and Waagepetersen98). Contrary to brain glucose utilisation, which is mainly dependent on neuronal activity, brain ketone utilisation is directly related to ketone concentrations in circulation over a broad range of concentrations, that is, from 0·1 to at least 6–7 mM of βHB(Reference Masino95), thus ensuring a continuous supply of energy to the brain during glucose scarcity.

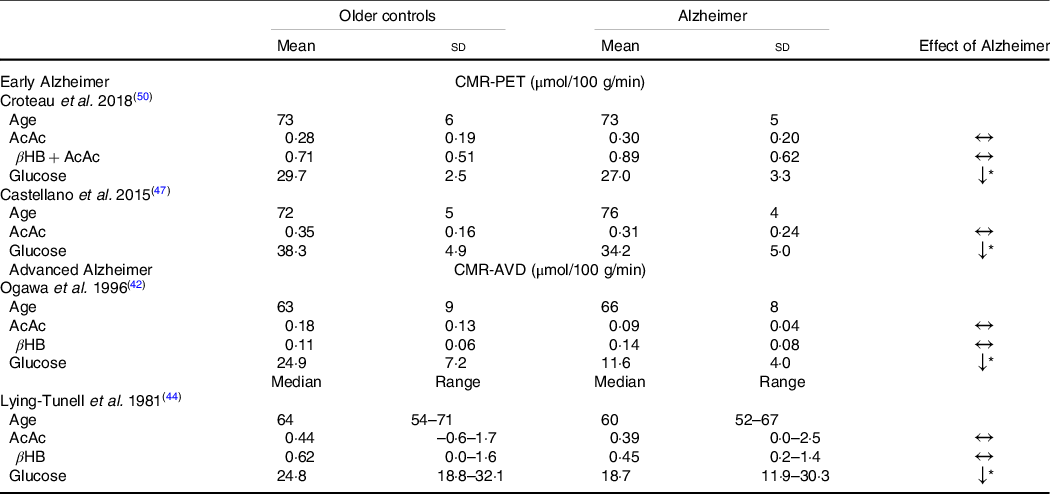

Despite the widespread characterisation of lower brain glucose utilisation in AD, few studies have evaluated the capacity of the brain to utilise its main alternative fuel – ketones – in AD. To the best of our knowledge, only four studies have directly evaluated brain glucose and ketone metabolism concomitantly in AD (Table 1). Using the arteriovenous difference method, Lying-Tunell et al. and Ogawa et al., reported that while CMR of glucose was impaired in moderate-advanced AD, CMR of AcAc and βHB remained similar to cognitively healthy, age-matched controls(Reference Ogawa, Fukuyama and Ouchi42,Reference Lying-Tunell, Lindblad and Malmlund44) . Decades later, these findings were confirmed using PET in mild-AD. We have also demonstrated that plasma AcAc concentrations and AcAc utilisation in healthy older adults, MCI and AD were all positively correlated with the same slope indicating a similar capacity of the brain to extract and utilise ketones despite the progression of cognitive decline(Reference Castellano, Nugent and Paquet47,Reference Croteau, Castellano and Fortier50) . Using a 4-year longitudinal study in healthy older adults, we later showed that while declining regional brain glucose utilisation (–6 to –12 %) was paralleled by deteriorating cognitive performance, AcAc utilisation remained unchanged over the same period(Reference Castellano, Hudon and Croteau99). A study in postmortem AD brains recently supported these in vivo observations by showing that while glycolytic gene expression was impaired in all cell types, ketolytic gene expression was normal in neurons, astrocytes and microglia but sub-normal in oligodendrocytes(Reference Saito, Miller and Harari100). Overall, the impairment in brain energy metabolism in AD clearly seems to be specific to glucose, which opens the possibility of providing ketones as an alternative substrate to the brain to reduce or bypass the energetic deficit in AD caused by BGH.

Table 1. Cerebral metabolic rate of ketones but not glucose remains normal in Alzheimer’s disease compared with healthy age-matched controls

(Mean values and standard deviations)

CMR-PET, cerebral metabolic rate measured by positron emission tomography; βHB, β-hydroxybutyrate; AcAc, acetoacetate; CMR-AVD, cerebral metabolic rate measured using the arteriovenous difference method.

Data are presented as mean (standard deviation) and as median (range) for as Lying-Tunell et al.

Significantly lower v. cognitively healthy age-matched older adults

* P < 0·05.

Ketogenic interventions

Research into the potential therapeutic applications of ketones has grown exponentially over the past decade and suggests that ketones may be clinically beneficial in several diseases including heart failure, diabetes and AD(Reference Gambardella, Morelli and Wang101–Reference Puchalska and Crawford103). Nutritional ketosis is usually defined as having a blood concentration of βHB or AcAc higher than 0·5 mM (Reference Harvey, Schofield and Williden104). It should be differentiated from pathological ketoacidosis in which plasma ketones are much higher (often ≥ 10 mM βHB + AcAc) but also because nutritional ketosis occurs without either an underlying disease or metabolic acidosis(Reference Green and Bishop105). Fasting and other dietary modifications resulting in mild endogenous ketosis have been used to treat a variety of diseases for centuries, including epilepsy(Reference Neal, Chaffe and Schwartz106), IR(Reference Accurso, Bernstein and Dahlqvist107), obesity(Reference Castellana, Conte and Cignarelli108) and neurodegenerative diseases(Reference Cunnane, Trushina and Morland39). Recently, the development of exogenous sources of ketones such as salts and esters permits plasma ketones to be raised independent of plasma glucose or insulin levels, widening the spectrum of potential therapeutic applications of this form of exogenous nutritional ketosis(Reference Soto-Mota, Norwitz and Clarke109).

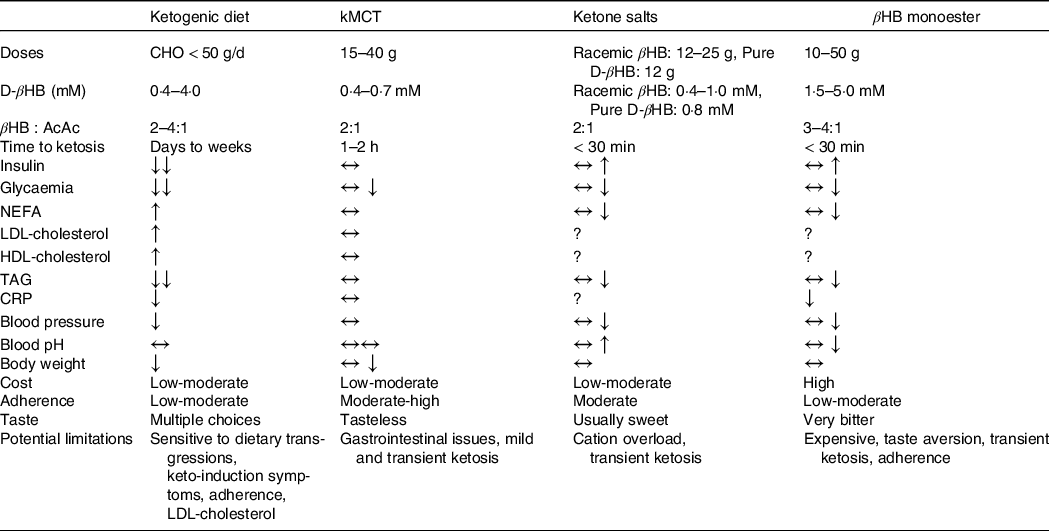

Endogenous ketosis

A KD will trigger metabolic and enzymatic adaptations that make the brain less reliant on glucose and favour the utilisation of ketones(Reference Courchesne-Loyer, Croteau and Castellano35,Reference Volek, Fernandez and Feinman110) . The blood profile that accompanies endogenous ketosis on KD (or fasting) differs from the one with exogenous ketosis(Reference Cahill111). First, given the low amount of carbohydrates consumed on a KD, glucose and insulin fluctuations are greatly reduced. Second, a KD promotes the release of NEFA from adipocytes through reduced insulin(Reference Choi, Tucker and Gross112), and increased counterregulatory hormones (e.g. glucagon, catecholamines, cortisol, growth hormones)(Reference Langfort, Pilis and Zarzeczny113,Reference Johnston, Pernet and McCulloch114) while βHB inhibits their mobilisation(Reference Taggart, Kero and Gan115). The effect of cortisol and glucagon on adipocytes is heavily influenced by insulin; when insulin is low, they promote lipolysis and ketogenesis and when insulin is high, they promote fat storage and lipogenesis(Reference Johnston, Pernet and McCulloch114,Reference Alberti, Johnston and Gill116) . In adults, short-term KD (≤ 4 weeks)(Reference Courchesne-Loyer, Croteau and Castellano35,Reference Phinney, Bistrian and Evans117,Reference VanItallie, Nonas and Di Rocco118) and its forms used for epilepsy (with or without MCT)(Reference Lambrechts, Wielders and Aldenkamp119) can produce moderate ketosis (βHB 1·5–4·0 mM). Nevertheless, longer-term studies (≥ 6 weeks) in MCI and AD(Reference Krikorian, Shidler and Dangelo120–Reference Taylor, Sullivan and Mahnken123) and other populations with(Reference Tay, Brinkworth and Noakes124–Reference Hallberg, McKenzie and Williams126) and without(Reference Brehm, Seeley and Daniels127–Reference McSwiney, Wardrop and Hyde129) chronic diseases have usually reported more modest βHB levels (< 1·0 mM). Additionally, since physical fitness, total energy intake, diet composition and metabolic profile influence ketone kinetics, it can be difficult to sustainably achieve a blood ketone target with a diet intervention alone(Reference Fukao, Lopaschuk and Mitchell130). Achieving endogenous ketosis can take many hours, sometimes days, and adherence to this relatively restrictive dietary pattern can be problematic(Reference Hu, Yao and Reynolds131), even more so if cognition and autonomy are already suboptimal. Ketogenic medium chain TAG (kMCT) can be used to supplement a KD to optimise ketone levels and to allow the introduction of some carbohydrates, thereby facilitating long-term adherence(Reference Liu and Wang132). The beneficial effects of a KD in reducing risk factors for AD such as IR, impaired glycaemic control, inflammation, and elevated blood pressure and body weight can outweigh the difficulties of adjusting to a KD(Reference Feinman, Pogozelski and Astrup133). While weight loss is usually beneficial for metabolic health in those who are overweight, it could potentially have deleterious effect in older people who are frail, sarcopenic or cachectic(Reference Bales and Buhr134). Similar to reports in populations without cognitive impairment(Reference Hallberg, McKenzie and Williams126,Reference Forsythe, Phinney and Fernandez135,Reference Hession, Rolland and Kulkarni136) , studies in MCI and AD using KD have reported significant improvements in body weight as well as circulating glucose, insulin and TAG, while both HDL- and LDL-cholesterol were increased(Reference Krikorian, Shidler and Dangelo120,Reference Neth, Mintz and Whitlow122,Reference Phillips, Deprez and Mortimer137) .

Not all fat sources are equally efficient in raising blood ketones(Reference St-Onge and Jones138). In the absence of carbohydrate restriction, among dietary fatty acids only octanoic acid and to a lesser extent, decanoic acid are truly ketogenic(Reference Ohnuma, Toda and Kimoto139–Reference Reger, Henderson and Hale142). Since kMCT are only found at very low levels in adipocytes and in the diet, they need to be repeatedly ingested to ensure their transformation into ketones within the liver(Reference You, Ling and Qu143). In cognitively healthy young and older adults, kMCT reduce postprandial glucose(Reference Vandenberghe, St-Pierre and Fortier144), have a neutral effect on fasting lipids and glucose and can moderately reduce body weight (–0·5 kg)(Reference Mumme and Stonehouse145,Reference Thomas, Stockman and Yu146) . The consumption of kMCT in MCI and AD for 4–24 weeks is safe and has no significant effects on body weight or plasma cardiometabolic and inflammatory marker profiles(Reference Myette-Côté, St-Pierre and Beaulieu147,Reference Xu, Zhang and Zhang148) . Their consumption, especially at high doses, can be associated with mild gastrointestinal issues in some patients, but they are usually transitory and can be tempered by dose titration(Reference Ohnuma, Toda and Kimoto139). Certain dietary patterns including intermittent fasting, time-restricted feeding(Reference de Cabo and Mattson149), energetic restriction(Reference Van Cauwenberghe, Vandendriessche and Libert29) and even coconut oil(Reference Vandenberghe, St-Pierre and Pierotti150,Reference Norgren, Sindi and Sandebring-Matton151) do not necessarily raise blood ketones, so their clinical and physiological implications fall outside the scope of this report.

Exogenous ketosis

Racemic ketone salts and βHB monoester produce plasma D-βHB of ∼1 and ∼3 mM for 24 g dose, respectively(Reference Stubbs, Cox and Evans152). In both cases, no dietary carbohydrate restriction is required, but given the transient nature of exogenous ketones, multiple daily ingestions may be necessary for therapeutic efficacy. Most but not all(Reference Cuenoud, Hartweg and Godin153) ketone salts are racemic, that is, containing both the d and the l form of βHB (of which only the d form is metabolisable into energy intermediates). Like with the esters, their half-life is too short to achieve a specific, sustained βHB blood level(Reference Soto-Mota, Norwitz and Clarke109). Nevertheless, ketone esters allow a similar level of blood βHB to be attained within 30 min to those observed after several days of fasting or following a KD(Reference Myette-Côté, Caldwell and Ainslie154). Moreover, they contain only D-βHB and are salt free(Reference Clarke, Tchabanenko and Pawlosky155). Their bitter taste and high price, however, currently limit their utility. The acute consumption of ketone salts and βHB monoesters transiently and mildly raise insulin secretion, an effect unlikely to be of clinical significance(Reference Stubbs, Cox and Evans152,Reference Myette-Côté, Caldwell and Ainslie154) . While both ketone salts and the βHB monoester raise blood βHB and lower blood glucose, NEFA and blood pressure, they have different metabolic and safety effects(Reference Stubbs, Cox and Evans152,Reference Myette-Côté, Caldwell and Ainslie154,Reference Holland, Qazi and Beasley156,Reference Soto-Mota, Vansant and Evans157) : Ketone salts transiently raise urine pH while ketone esters transiently decrease it and, when comparing equimolar doses, the ketone monoester raises chloride more than ketone salts(Reference Stubbs, Cox and Evans152,Reference Dearlove, Faull and Rolls158) . On the other hand, the Na content to achieve therapeutic levels of blood βHB using most commercially available ketone salts exceeds the recommended upper limit. To date, no RCT has investigated the effect of oral ketone supplementation in populations with cognitive decline although one is currently in progress (Clinicaltrials.gov identifier: NCT04466735).

The understanding of the acute and short- to medium-term (1–24 weeks) effect of different ketogenic interventions on cardiometabolic markers has considerably expanded in recent years (summarised in Table 2), but whether there are potential long-term side effects of the non-physiological environment accompanying exogenous ketosis (i.e. elevated glucose, ketones and insulin simultaneously) is still unknown and will need to be determined in order to optimise the safety and efficacy of ketogenic interventions in different therapeutic contexts.

Table 2. Characteristics and general effects of ketogenic interventions

kMCT, ketogenic medium chain TAG (C8 and C8C10 combined); βHB:AcAc, β-hydroxybutyrate:acetoacetate ratio in the blood; BW, body weight; CHO, carbohydrates; IR, insulin resistance; AD, Alzheimer’s disease.

Fuel efficiency: a core feature of ketones

Besides substituting for glucose as a fuel, there are three reasons why ketones are a more efficient source of carbon to fuel the mitochondrial respiratory chain than glucose or NEFA: First, ketones are more reduced than pyruvate (higher hydrogen to carbon ratio), so have a higher redox potential or potential to generate ATP(Reference Veech159). Second, in contrast with fatty acid oxidation which promotes the expression of uncoupling proteins (via PPARα transcription regulation), ketone oxidation is electrochemically more efficient to produce ATP. During fatty acid β-oxidation, only half of the reducing equivalents are NADH while the other half are FADH (which has a redox potential above that of the NAD couple) resulting in the synthesis of five instead of the six possible ATP molecules(Reference Veech159). Third, because of the dual role of succinate dehydrogenase in the Krebs cycle and electron transport chain, half of the reducing equivalents enter the electron transport chain via Complex II during ketone β-oxidation instead of Complex I(Reference Veech159). Complex II has a smaller reduction potential with the Q-couple (which is near equilibrium) than Complex I (–0·320 mV for the NAD couple(Reference Ramsay160) v. +0·32 mV for the fumarate and succinate couple(Reference Kracke, Vassilev and Krömer161)). This larger gradient results in more electrochemical energy available to fuel ATP production during ketones oxidation(Reference Veech162,Reference Sato, Kashiwaya and Keon163) . Furthermore, most reactive oxygen species in the cell are produced in mitochondria, principally at the electron transfer step between Complex I and the Q-couple. Since ketone oxidation preserves the Q-couple in the oxidised state (as opposed to glucose or fatty acid β-oxidation), fewer reactive oxygen species are produced during ketolysis than during β-oxidation. Ketolysis also expands the citric cycle metabolite pool, despite a lower concentration of glycolysis intermediates.

Keto-therapeutics for brain energetics, cognition and neuroprotection

In healthy humans(Reference Courchesne-Loyer, Croteau and Castellano35) and rodent models(Reference LaManna, Salem and Puchowicz164), total brain energy levels remain unchanged following a KD because the increase in brain ketone utilisation is paralleled by a compensatory reduction in glucose utilisation. This homoeostatic mechanism is not observed in populations with cognitive impairments in whom ketones help fill in the energetic deficit and increase total energy levels in the brain without reducing brain glucose utilisation(Reference Neth, Mintz and Whitlow122,Reference Fortier, Castellano and Croteau141,Reference Croteau, Castellano and Richard165) . Even at low levels of ketosis (βHB ∼0·6 mM), we previously showed using 11C-AcAc- and 18FDG-PET that long-term consumption of 30 g/d of kMCT significantly increased whole-brain CMR of ketones by 230 % in MCI and 144 % in AD without affecting CMR of glucose. The result was a net improvement in total brain energy consumption of 3–4 % in both groups(Reference Fortier, Castellano and Croteau141,Reference Croteau, Castellano and Richard165) . Neth et al. also observed increased brain perfusion and ketone body utilisation in individuals with subjective memory complaints or MCI on a KD(Reference Neth, Mintz and Whitlow122). Thus, ketones effectively compensate for at least part of the energy deficit in older populations with cognitive decline. Importantly, Neth et al. (Reference Neth, Mintz and Whitlow122) and Fortier et al. (Reference Accurso, Bernstein and Dahlqvist107) included cognitive performance as a secondary outcome in their trial. While both studies reported some improvement in cognition following the use of a ketogenic Mediterranean diet(Reference Neth, Mintz and Whitlow122) or kMCT(Reference Fortier, Castellano and Croteau141) in subjective memory complaints and MCI, they were not powered to adequately assess cognitive changes post-intervention. Thus, the first phase of the BENEFIC trial reported by Fortier et al. (Reference Fortier, Castellano and Croteau141) was extended by doubling the sample size so as to better evaluate cognitive outcomes. As compared with an energy-matched drink, the consumption of kMCT for 6 months led to clinically meaningful improvements in several cognitive domains related to the risk of progression towards AD including episodic memory, language, executive function and processing speed(Reference Fortier, Castellano and St-Pierre166).

Several other trials as well as a few case studies using ketogenic interventions in MCI and AD have reported benefits on global cognition (ADAS-CoG) and memory(Reference Krikorian, Shidler and Dangelo120,Reference Brandt, Buchholz and Henry-Barron121,Reference Taylor, Sullivan and Mahnken123,Reference Henderson, Vogel and Barr140,Reference Reger, Henderson and Hale142,Reference Xu, Zhang and Zhang148,Reference Ota, Matsuo and Ishida167–Reference Farah169) or quality-of-life and activities of daily living(Reference Phillips, Deprez and Mortimer137) as compared with placebo or pre-intervention status (Table 3). Two systematic reviews and meta-analyses recently concluded that, though preliminary, available evidence suggests that ketogenic interventions constitute an effective and feasible approach to improve cognition in older populations with cognitive impairment(Reference Avgerinos, Egan and Mattson170,Reference Grammatikopoulou, Goulis and Gkiouras171) . While it is possible that the APOE4 allele induces a lower change in blood βHB, brain blood flow and cognition in response to a ketogenic supplement(Reference Henderson, Vogel and Barr140,Reference Reger, Henderson and Hale142,Reference Torosyan, Sethanandha and Grill172) , other studies reported no difference between APOE phenotypes(Reference Brandt, Buchholz and Henry-Barron121,Reference Fortier, Castellano and Croteau141) . Given the existing heterogeneity in the ketogenic interventions, small sample size, and different populations and duration of the studies (see Table 3), it remains to be determined how best to optimise ketones to improve cognitive performance in older people.

Table 3. Nutritional studies using keto-therapeutics in populations with cognitive impairment linked to Alzheimer’s disease

ADAS-Cog, Alzheimer’s disease assessment scale-cognitive subscale; AD, Alzheimer’s disease; βHB, β-hydroxybutyrate; C8, caprylic acid; C10, capric acid; CHO, carbohydrates; DC, dosage compliant; HCLF, high-carbohydrate low-fat diet; ITT, intention-to-treat; KD, ketogenic diet; MCI, mild cognitive impairment; MCT, medium chain TAG; MEC-WOLF, mini examen cognoscitivo (Spanish adaptation of the MMSE); RCT, randomised controlled trial; SMS, subjective memory complaints.

* Fortier et al. (2021) extended the recruitment from Fortier et al. (2019) by adding forty more participants.

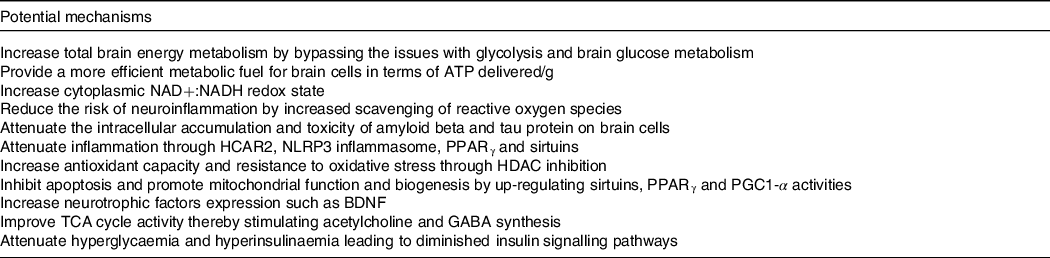

Our work over the last two decades suggests that ketogenic interventions improve cognitive performance principally by reducing the existing brain energy deficit through the provision of an insulin-independent alternative fuel to glucose, that is, ketones. However, using keto-therapeutics in rodent models, several other signalling, metabolic and epigenetic actions that may confer neuroprotection and improve cognitive impairment have been suggested (reviewed here(Reference Yang, Shan and Zhu173–Reference Pinto, Bonucci and Maggi177)) (Table 4). So far, only one human study evaluating the effect of ketogenic interventions on traditional neuropathological hallmarks of AD has been reported. In this 6-week pilot study in older adults at risk for AD, a ketogenic Mediterranean diet increasing βHB levels to ∼1·0 mM increased β-amyloid 42 and reduced tau levels in cerebrospinal fluid, both of which are considered as positive changes(Reference Neth, Mintz and Whitlow122). In mouse models of AD, substantial evidence depicting a reduction in intracellular accumulation and toxicity of amyloid beta and tau protein on brain cells as well as neuroinflammation using both KD and exogenous ketones has been published(Reference Kashiwaya, Takeshima and Mori178–Reference Kashiwaya, Bergman and Lee182). Given that very different ketogenic interventions (i.e. KD v. ketone ester) seem to provide some cognitive benefits and potentially very rapidly (within 2 h), it is likely that the role of ketones themselves as an efficient fuel is directly involved in the observed benefit, at least in the short term. The optimal therapeutic levels of ketones to achieve long-term neuroprotection and cognitive benefits in humans remain unknown, which could be an order of magnitude lower than the levels tested so far in most rodent models of AD (3–5 mM). Importantly, part of the clinical benefits attributed to some ketogenic interventions in populations with cognitive decline may not be due to the actions of ketones as fuels but rather to other effects of specific kMCT. For example, as compared with other medium-chain TAG, decanoic acid may offer superior neuroprotection through mechanisms that might include increased peroxisomal proliferator-activated receptor-γ activation, mitochondrial biogenesis and inhibition of α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazole propionic acid (AMPA) receptors (reviewed here(Reference Augustin, Khabbush and Williams174)). Given the distinctions that exist between traditional KD, modified medium-chain TAG KD and kMCT supplementation (i.e. kMCT and carbohydrate contents), future studies should investigate whether the effect on cognition in MCI and AD differs between these two ketogenic strategies.

Table 4. Potential mechanisms involved in the improvement of cognitive impairment and neuroprotection by ketogenic interventions in AD

Based on references(Reference Augustin, Khabbush and Williams174–Reference Pinto, Bonucci and Maggi177).NAD, nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide; NADH, nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide hydrogen; HCAR2, hydroxycarboxylic acid receptor 2; NLRP3, nucleotide oligomerisation domain-like receptor family pyrin domain containing 3; HDAC, histone deacetylase; PGC1-α, peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma co-activator-1 alpha; BDNF, brain-derived neurotrophic factor; TCA, tricarboxylic acid; GABA, neurotransmitter γ-aminobutyric acid.

Physical activity as an adjunct to keto-therapeutics in populations with cognitive deficits

Physical inactivity is thought to contribute to ∼8·0 % of dementia cases globally(Reference Katzmarzyk, Friedenreich and Shiroma183). Nevertheless, there are currently no official physical activity guidelines specifically for individuals with AD who need to defer to those for healthy older adults and/or for other health conditions(Reference Ross, Chaput and Giangregorio184). In older adults without cognitive dysfunction, physical activity is inversely associated with the risk of AD, with the APOE4 allele potentially diminishing(Reference Tan, Spartano and Beiser185) or strengthening(Reference Rovio, Kåreholt and Helkala186) the relationship. Importantly, home-based and group-based exercise interventions have been shown to be feasible and improve quality of life, physical performance and the ability to perform daily activities in both older adults with and without cognitive deficit(Reference Suttanon, Hill and Said187–Reference Pitkälä, Pöysti and Laakkonen189). Though controversial, several recent meta-analyses in MCI and AD patients themselves support the idea that exercise interventions, especially the aerobic type, might slow down the decline of global cognition(Reference Jia, Liang and Xu190–Reference Zheng, Xia and Zhou193). However, most of the evidence remains of low to moderate quality and has a low effect sizes, so definitive conclusions would be premature. The regular practice of physical activity improves several major risk factors for AD including blood lipids, hypertension, cardiorespiratory fitness(Reference DeFina, Willis and Radford194) and peripheral IR(Reference Joyner and Green195), the latter being inversely associated with regional BGH(Reference Willette, Bendlin and Starks84). It is likely that exercise treatment should be initiated as early as possible in the AD process to minimise the effect of the patients’ potential physical and mental health decline on their capacity to sustain an exercise dose sufficient to yield health benefits. In rodent experiments, exercise restores mitochondrial ATP production, lowers reactive oxygen species emission and improves tau pathology through improved insulin action in the insulin-resistant brain(Reference Ruegsegger, Vanderboom and Dasari196). Exercise also reduces brain amyloid in transgenic AD mice(Reference Adlard, Perreau and Pop197,Reference Um, Kang and Leem198) , but so far interventional studies assessing cerebrospinal fluid A β 1–42 have failed to see similar results in AD(Reference Jensen, Portelius and Siersma199), though some interesting trends were observed in older adults at risk of AD(Reference Baker, Frank and Foster-Schubert200,Reference Baker, Frank and Foster-Schubert201) . Determining whether exercise improves cognition by correcting brain IR will provide important information for future AD therapy.

Multidomain lifestyle interventions including exercise and cognitive training with and without diet improve and maintain cognitive function in older adults at risk for AD(Reference Lauenroth, Ioannidis and Teichmann202,Reference Ngandu, Lehtisalo and Solomon203) , potentially more than exercise alone(Reference Brasure, Desai and Davila204). While both physical activity(Reference Brown, Peiffer and Martins205) and nutritional ketogenic interventions(Reference Grammatikopoulou, Goulis and Gkiouras171) independently improve brain health and cognition, no RCT have evaluated their combined effect on cognitive function in populations at risk of or living with cognitive decline. To the best of our knowledge, only a single case study using high-intensity interval training and KD along with cognitive training for 12 weeks in a 57-year-old woman with MCI has been published and reported a significant improvement in cognition (+8 points; MoCA) and biomarkers of the metabolic syndrome(Reference Dahlgren and Gibas206). Although cognition was not assessed in their studies, Miller et al. did look at the combined effect of exercise and KD in healthy young individuals and reported significant improvements in skeletal muscle mitochondrial function and efficiency(Reference Miller, LaFountain and Barnhart207). Myette-Côté et al. reported better glucose control and endothelial function following a 4-d KD combined with exercise as compared with both KD alone and a low-fat low-glycaemic index diet in type 2 diabetes(Reference Myette-Côté, Durrer and Neudorf208,Reference Francois, Myette-Cote and Bammert209) .

Prolonged glycogen-depleting exercise has long been known to stimulate ketone turnover and induce a marked rise in blood ketone concentrations especially during the recovery period when fatty acid oxidation is elevated(Reference Balasse and Féry210,Reference Fery and Balasse211) . In normoglycaemic but not in mildly hyperglycaemic individuals, aerobic exercise potentiates the plasma ketone response (+69 %) to kMCT supplementation; whether the same would apply in AD has not been assessed(Reference Vandenberghe, Castellano and Maltais212). Along these lines, one study in both mice and older adults reported that aerobic exercise but not resistance training was effective at raising blood βHB levels and improving cognition which might help guide the optimal exercise modality to select in AD(Reference Kwak, Bae and Lee213).

Factors such as fitness level, pre-exercise ketone levels, exercise intensity and metabolic status can influence muscle ketone disposal by as much as 2–5-fold(Reference Evans, Cogan and Egan214). Unfortunately, studies on brain ketones utilisation during exercise are scarce with one showing no change in brain substrate utilisation (ketones, lactate, glycerol) in young adults during prolonged exercise when βHB levels remained relatively low ∼0·4 mM(Reference Ahlborg and Wahren215). More recently, we showed that in AD, exercise increases ketone transport into the brain, thereby translating into a higher contribution of ketones to total brain energy. Indeed, mild to moderate exercise bouts (50 % VO2max for 40 min) performed over 3 months significantly increased both plasma ketones (+0·3 mM) and tripled CMR of AcAc (from 0·2 (sd 0·1) μmol/100 g/min to 0·6 (sd 0·4)) without affecting CMR of glucose(Reference Castellano, Paquet and Dionne216). Thus, combining a ketogenic intervention and exercise would be expected to have a more pronounced benefit for brain energy metabolism and would potentially be associated with better cognitive performance. While moderate physical activity level has previously been associated with higher CMR of glucose in older adults at risk of AD(Reference Dougherty, Schultz and Kirby217), Gaitan et al. failed to observe a significant change in CMR of glucose following a 26-week exercise intervention in the same population(Reference Gaitán, Boots and Dougherty218). Interestingly, Porto et al. (Reference Henrique de Gobbi Porto, Martins Novaes Coutinho and Lucia de Sá Pinto219) and Shah et al. (Reference Shah, Verdile and Sohrabi220) reported that exercise interventions did improve regional brain glucose utilisation in MCI and older adults, respectively. Though the reason for this discrepancy remains uncertain, these interventions all led to some cognitive benefits that were correlated with changes in regional 18FDG metabolism which highlights the potential of exercise to improve AD-related symptoms through a mechanism linked to improved brain energy metabolism.

While this has not been evaluated in AD, a recent study showed that exogenous ketosis improved exercise tolerance in patients living with Parkinson’s disease suggesting that ketogenic interventions could improve adherence and, consequently, facilitate access to exercise-induced cognitive improvements(Reference Norwitz, Dearlove and Lu221). Moreover, βHB produced during exercise or with ketogenic interventions promoted the expression of brain-derived neurotrophic factor in healthy humans(Reference Walsh, Myette-Côté and Little222,Reference Coelho, Vital and Stein223) , and in AD, a state characterised by low levels of brain and circulating brain-derived neurotrophic factor (Reference Lee, Fukumoto and Orne224,Reference Sleiman, Henry and Al-Haddad225) . Increased brain-derived neurotrophic factor has been proposed as one potential mechanism to explain the observed cognitive improvement in AD with ketogenic interventions as it is involved in numerous neurophysiological processes that contribute to neuronal growth and survival as well as synaptic plasticity(Reference Maalouf, Rho and Mattson175). Importantly, ketogenic interventions and exercise stimulate mitochondrial biogenesis and ATP generation through oxidative metabolism in neurons(Reference Bough, Wetherington and Hassel226,Reference Steiner, Murphy and McClellan227) . Mitochondrial dysfunction and aberrant energy metabolism constitute critical factors in the pathogenesis of AD that could potentially be prevented or slowed down by combining these two therapeutic approaches. In addition to their effect on energy metabolism, exercise and ketogenic interventions share different adaptive responses in the brain that could contribute to cognitive health and resilience including neurogenesis, synaptic plasticity as well as protection against neuroinflammation, reactive oxygen species and potentially proteotoxicity(Reference Brown, Peiffer and Martins205,Reference Cotman and Berchtold228,Reference Van Praag, Fleshner and Schwartz229) . KD and exercise are also potent stimulators of monocarboxylate transporter expression, which are responsible for the passage of ketones across the blood–brain barrier(Reference Leino, Gerhart and Duelli230,Reference Takimoto and Hamada231) . Taken together, exercise has several overlapping and synergistic effects with keto-therapeutics that could potentially play a key role in the treatment and maybe prevention of AD. Thus, it is of great interest to further investigate the practical limits of combining exercise as an adjunct to ketogenic interventions, bearing in mind that their joint feasibility and effectiveness will likely depend on factors such as physical capacity, motivation and disease stage.

Current challenges and future directions

The aetiology of AD is complex and will most likely require early initiation of a multi-target treatment to significantly improve clinical outcomes(Reference Long and Holtzman16). Ketogenic interventions reduce not only the brain energy deficit but also oxidative stress and neuroinflammation, while improving mitochondrial function. BGH alone is probably not sufficient to cause AD-related cognitive impairment, but it certainly aggravates the deleterious effects of neuropathophysiological processes and worsens clinical prognosis(Reference Norwitz, Mota and Norwitz78). Equally, the clinical studies reviewed here show that BGH can be bypassed by a ketogenic intervention and in so doing improve cognitive outcomes, at least in MCI(Reference Fortier, Castellano and Croteau141,Reference Fortier, Castellano and St-Pierre166) . Hence, brain energy rescue is part of the solution; pharmaceutical or non-pharmaceutical interventions in MCI and AD would therefore be predicted to have a better chance of success if they include some form of brain energy rescue.

As to future directions for the field, we have a few suggestions: First, the majority of studies using ketogenic interventions in MCI and AD have been pilot, safety or feasibility trials and were underpowered to detect differences in cognitive outcomes. Thus, it will be critical for future trials to include larger sample sizes to draw more valid conclusions regarding the effectiveness of such treatments to delay cognitive decline associated with AD. Second, although a KD induces higher overall ketosis than exogenous ketones, poor long-term compliance to such a strict diet is an important barrier to its long-term application. The utilisation of exogenous ketones alone or with KD might help alleviate this barrier by allowing a more permissive diet. In type 2 diabetes, the use of continuous remote care during KD interventions that provides patients with access to a healthcare team and biomarkers tracking tools through a web-based application recently showed great diet compliance after 2 years(Reference Athinarayanan, Adams and Hallberg232). This novel system will hopefully be applied to populations with AD and MCI attempting to manage their conditions using KD. As clinical experience with ketogenic interventions grows, it is becoming clearer that cardiometabolic markers do not change adversely during studies of up to 6 months, thereby indicating a good margin for safety.

So far, most ketogenic interventions in MCI and AD have resulted in relatively low plasma βHB concentrations (0·3–0·9 mM, see Table 2). Since neurocognitive test performance in MCI is directly related to overcoming BGH by brain ketone utilisation in a dose–response relationship(Reference Krikorian, Shidler and Dangelo120,Reference Henderson, Vogel and Barr140–Reference Reger, Henderson and Hale142) , it is likely that further increasing ketone levels to reduce the brain energy gap as much as possible might yield additional cognitive or functional benefits. To achieve a somewhat higher plasma ketone response and better compliance than with a kMCT or KD, we recently launched the BREAK-AD RCT in MCI using a ketone salt (25 g/d of D-βHB) (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT04466735). Third, ketones are part of an effective strategy to delay AD but much work needs to be done to optimise their use in people at risk of AD because even the simplest option of taking 20–30 g/d of a ketogenic supplement for the rest of one’s life is still a significant lifestyle change. Exercise is important for well-being and cardiometabolic health and improves ketone delivery to the brain in AD, so should always be encouraged in moderation. More broadly, improving sleep and reducing anxiety and depression will also be beneficial. Correcting impairing hearing is also important as is social engagement. Existing drugs (or those in development) for AD could well be more effective with concomitant brain energy rescue using a ketogenic intervention. This is quite plausible because ketones may not improve neurotransmitter status or reduce amyloid or P-tau load but remains to be assessed. Fourth, with a large proportion of the older population in nursing homes or homes for assisted living, a concerted effort to run RCT in such a setting will be important in the near future. Logistical advantages of such a setting include the proximity of the participants to one another and group meals and other activities. Finally, we now have a solid rationale for a multi-modal AD prevention trial starting no later than in MCI; core components would include a ketogenic intervention, moderate exercise and a MIND-type diet including carbohydrate reduction. The Worldwide Fingers network(Reference Kivipelto, Mangialasche and Snyder233) is a solid foundation for a new era of prevention trials in AD and will hopefully include a trial site using a keto-therapeutic intervention in the years to come.

Acknowledgements

Mélanie Fortier, Valérie St-Pierre, Christian Alexandre Castellano, Audrey Perreault, Etienne Croteau, Camille Vandenberghe and Marie-Christine Morin provided valuable technical assistance.

Étienne Myette-Côté is supported by the Alzheimer Society Research Program (Alzheimer Society of Canada) and the Fonds de Recherche en Santé du Québec (FRSQ). Adrian Soto-Mota is supported by the National Institute of Medical Sciences and Nutrition Mexico. Stephen C. Cunnane is supported by the Alzheimer Association USA, FRQS, Mitacs, the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC) and Nestlé Health Science.

E. M. C., A. S. M. and S. C. C. all (1) substantially contributed to the conception and design of the article and interpreting the relevant literature and (2) drafted the article and revised it critically for important intellectual content.

Étienne Myette-Côté and Adrian Soto-Mota declare that they have no conflict of interest. Stephen C. Cunnane declares that he has consulted for or received travel honoraria, test products or research funding from Abitec, Cerecin, Bulletproof, Nestlé Health Science and Servier. SCC is the founder of Senotec and is co-inventor on a patent for a medium chain triglyceride formulation.