Skeletal muscle is an important component of an organism. The evolutionary processes of skeletal muscle development involves several steps including myoblast proliferation, differentiation, fusion into multinuclear myotubes and the formation of myofibres( Reference Buckingham 1 , Reference Sabourin and Rudnicki 2 ). During these highly coordinate processes, myoblast differentiation is a necessary and vital procedure for myogenesis, which is controlled by a complex set of tissue-specific transcription factors called the myogenic regulatory factors (MRF) involving myogenic determining factor (MyoD), myogenic factor 5 (Myf5), myogenin and MRF4( Reference Rudnicki and Jaenisch 3 , Reference Sassoon 4 ). Amidst MRF, MyoD determines the myogenic fate in myogenesis, whereas myogenin controls terminal differentiation( Reference Arnold and Winter 5 , Reference Perry and Rudnick 6 ). These factors could stimulate the expression of muscle-specific genes such as myosin heavy chain (MHC) and creatine kinase (CK) activity, and then coordinate myoblast differentiation( Reference Sabourin and Rudnicki 2 ). The process is also controlled by a multitude of signalling cascades initiated by various autocrine/paracrine growth factors such as insulin-like growth factors and the protein kinase B (Akt)/Forkhead box O1 (FoxO1) pathway( Reference Florini, Ewton and Coolican 7 , Reference Kornasio, Riederer and Butler-Browne 8 ). Protein kinase B, also known as Akt, plays a critical role in control of myoblast differentiation( Reference Tureckova, Wilson and Cappalonga 9 ). Blockage of Akt or silencing of Akt inhibits the differentiation of skeletal muscle; however, overexpression of Akt gets an opposite result( Reference Rotwein and Wilson 10 , Reference Woo, Yun and Kim 11 ). FoxO1 is one of FoxO family members, and it plays a significant role in regulating myoblast differentiation. Inhibition of FoxO1 by siRNA promotes C2C12 cell differentiation, whereas overexpression of FoxO1 decreases the protein level of myogenin( Reference Yuan, Shi and Liu 12 ).

Leucine, one of the branched-chain amino acids, cannot be synthesised in mammals and must be provided by feeding. Under the catalysis of branched-chain amino acid transaminase and branched-chain amino acid dehydrogenase, leucine can be transformed into acetoacetic acid and acetyl-CoA and then take part into the citric acid cycle and provide energy for the body( Reference Desantiago, Torres and Suryawan 13 ). The metabolism of leucine is mainly in the skeletal muscles, which is likely because the key enzymes involved in leucine metabolism are mainly distributed in skeletal muscle( Reference Shimomura, Honda and Shiraki 14 ). Skeletal muscle is the main site for storage of free amino acids and proteins( Reference Wagenmakers 15 ). Protein synthesis and degradation are of extraordinary importance to animals. The protein deposition of skeletal muscle is the result of the balance of protein synthesis and degradation. Leucine is the most effective amino acid to regulate muscle protein turnover. It has been reported that leucine not only increases muscle protein synthesis( Reference Anthony, Anthony and Kimball 16 – Reference Wang, Yang and Wang 19 ) but also decreases muscle protein degradation( Reference Hernandez-Garcia, Columbus and Manjarin 17 , Reference Hong and Layman 18 , Reference Mitch and Clark 20 ). Except for studies on muscle protein metabolism, there are several recent studies on the role of leucine in differentiation of mouse C2C12 cells and rat satellite cells( Reference Averous, Gabillard and Seiliez 21 , Reference Dai, Yu and Shen 22 ), but no study has been conducted on its role in porcine myoblast differentiation. Although murine cell lines have contributed to important insight into myogenesis, nutrients, microRNA and other factors might play disparate effect during myogenesis between murine cell lines and primary cells from domesticated mammals. For example, treatment of melengestrol acetate increases myogenin mRNA expression in C2C12 cells, but no affect is observed in bovine muscle satellite cells( Reference Sissom, Reinhardt and Johnson 23 ). miR-27a has the opposite role on differentiation between C2C12 cells and porcine myoblasts( Reference Chen, Huang and Chen 24 , Reference Zhang, Chen and Huang 25 ). Therefore, study on role of leucine in porcine myoblast differentiation is absolutely essential.

In this study, we hypothesised that leucine could affect differentiation of porcine myoblasts and this function might be dependent on Akt/FoxO1 signalling. The aim of this study was to investigate the role of leucine in differentiation of porcine myoblasts.

Methods

Ethics statement

All animal procedures were performed according to protocols approved by the Animal Care Advisory Committee of Sichuan Agricultural University.

Isolation and primary culture of porcine myoblasts

Primary myoblasts were isolated from longissimus lumborum muscle of 3-d-old male Duroc×Landrace×Yorkshire pigs. Segregated muscle was washed once in 75 % ethyl alcohol and three times in cold PBS (pH 7·4), cut into pieces and then digested in 0·2 % type II collagenase (Sigma) for 30 min at 37°C. The tissue suspension was centrifuged (1500 rpm, 10 min) and the precipitate continued to digest in 0·25 % trypsin (Invitrogen) for 20 min. To terminate digestion, the growth medium containing DMEM/F12 (Invitrogen) with 15 % fetal bovine serum (Invitrogen) and 1 % antibiotics (100 U/ml penicillin and 100 μg/l streptomycin) (Invitrogen) was added. The cell suspension was filtered through 200- and 400-mesh cell strainers and centrifuged (1500 rpm, 10 min). The precipitate was resuspended in the growth medium and amplified in culture flasks. The cells were purified by differential adhesion method. Porcine myoblasts were cultured in the growth medium at 37°C in a saturated humid atmosphere containing 5 % CO2. When porcine myoblasts reached approximately 80 % confluence, the cells were seeded in six-well culture plates at 5×104 cells/well and grown in growth medium. To induce differentiation, cells grown to approximately 80 % confluence were shifted to differentiation medium containing DMEM/F12 with 2 % horse serum (Invitrogen).

Creatine kinase assay

CK activity was used to assess myogenic differentiation biochemically. Cells were washed with PBS, digested in 0·25 % trypsin (Invitrogen) for 2 min and lysed in PBS containing 1 % Triton X-100. Lysates were centrifuged at 14 000 g for 10 min at 4°C to remove insoluble material. The protein concentrations were determined using the bicinchoninic acid (BCA) protein assay kit (Pierce) by a Nano-Drop ND 2000c Spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific). CK activity was measured using a CK enzymatic assay kit (Nanjing Jiancheng Bioengineering Institute), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. A volume of 300 μl of CK reagent was added to 20 μl of cell lysate, and then CK activity was immediately measured at 660-nm wavelength. Enzymatic specific activity of CK was calculated after calibration for total protein concentration and defined as units per milligram of protein (U/mg).

Immunofluorescence analysis

After treatment, the cells were fixed in fixation fluid (Beyotime) for 15 min at room temperature, washed three times with PBS, permeabilised in 0·5 % Triton X-100 for 20 min, washed three times with PBS and then blocked with blocking buffer (Beyotime) for 2 h at 37°C. After washing three times with PBS, the cells were incubated with MHC primary antibody (1:100, catalogue no. MF-20; DSHB) at 4°C overnight. After washing three times with PBS, the cells were stained with fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated secondary antibody (1:500; Santa Cruz) for 2 h at 37°C. After washing three times with PBS again, nuclei were counterstained with 4,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (Invitrogen). Images were taken on a fluorescence microscope (version 6.0.0.260; Media Cybernetics, Inc.).

Reverse transcription and real-time quantitative PCR

RNAiso Plus reagent (TaKaRa) was used to extract total RNA from porcine myoblasts. The concentrations of RNA were determined by Nano-Drop ND 2000c Spectrophotometer. A measure of 1 µg of total RNA from each sample was used to synthesise into complementary DNA using a PrimeScript® RT reagent Kit with gDNA Eraser (TaKaRa) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Real-time quantitative PCR was carried out in a 7900HT real-time PCR system (384-cell standard block) (Applied Biosystems) using the SYBR select Master Mix (Applied Biosystems) in a final volume of 10 µl. The primer sequences used for quantification of mRNA expression were as follows: porcine myogenin (forward) 5'-CGCCATCCAGTACATCGAG-3' and (reverse) 5'-TGTGGGAACTGCATTCACTG-3'; porcine MyoD (forward) 5'-AAGACCACTAACGCCGACC-3' and (reverse) 5'-AGTCTCGAAGGCCTCGTTG-3'; porcine β-actin (forward) 5'-CATCGTCCACCGCAAAT-3' and (reverse) 5'-TGTCACCTTCACCGTTCC-3'. Relative expression of mRNA was quantified using

![]() $$2^{{{\minus}\Delta \Delta C_{t} }} $$

method and was normalised by β-actin mRNA.

$$2^{{{\minus}\Delta \Delta C_{t} }} $$

method and was normalised by β-actin mRNA.

Western blot

Porcine myoblasts were washed with PBS and then lysed in radio-immunoprecipitation assay cell lysis buffer (Pierce). The cell lysates were centrifuged at 14 000 g for 15 min at 4°C and the protein concentrations were determined using the BCA protein assay kit by Nano-Drop ND 2000c Spectrophotometer. The protein lysates were denatured after boiling with 5×protein loading buffer for 10 min. An equal amount of proteins (20 µg) were separated by 12 % SDS–polyacrylamide gel and transferred onto polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) membrane (Millipore) using wet Trans-Blot system (Bio-Rad). After blocking with 5 % bovine serum albumin in Tris-buffered saline/Tween-20 (TBS/T) for 2 h at room temperature, the membranes were incubated at 4°C overnight with primary antibodies against myogenin (1:50, catalogue no. sc-12732; Santa Cruz), MyoD (1:50, catalogue no. sc-304, Santa Cruz), Akt (1:1000, catalogue no. 9272; Cell Signaling), phosphorylated Akt (P-Akt) (1:1000, catalogue no. 9271; Cell Signaling), FoxO1 (1:1000, catalogue no. 2880; Cell Signaling), phosphorylated FoxO1 (P-FoxO1) (1:1000, catalogue no. 9461; Cell Signaling), glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) (1:3000, catalogue no. sc-20357; Cell Signaling) or β-actin (1:3000, catalogue no. sc-1616; Cell Signaling). The PVDF membranes were washed three times with TBS/T and incubated with second antibodies at room temperature for 1 h. Signals were visualised by using a ClarityTM Western ECL Substrate (Bio-Rad) and then quantified by the Gel-pro Analyzer (Media Cybernetics Inc.). The ratio of target protein expression was normalised to GAPDH or β-actin.

Statistical analysis

Each experiment was performed three times and all data were expressed as means with their standard errors. One-way ANOVA and Tukey’s tests (SPSS Inc.) were performed. P<0·05 was regarded as statistically significant.

Results

Leucine promotes differentiation of porcine myoblasts

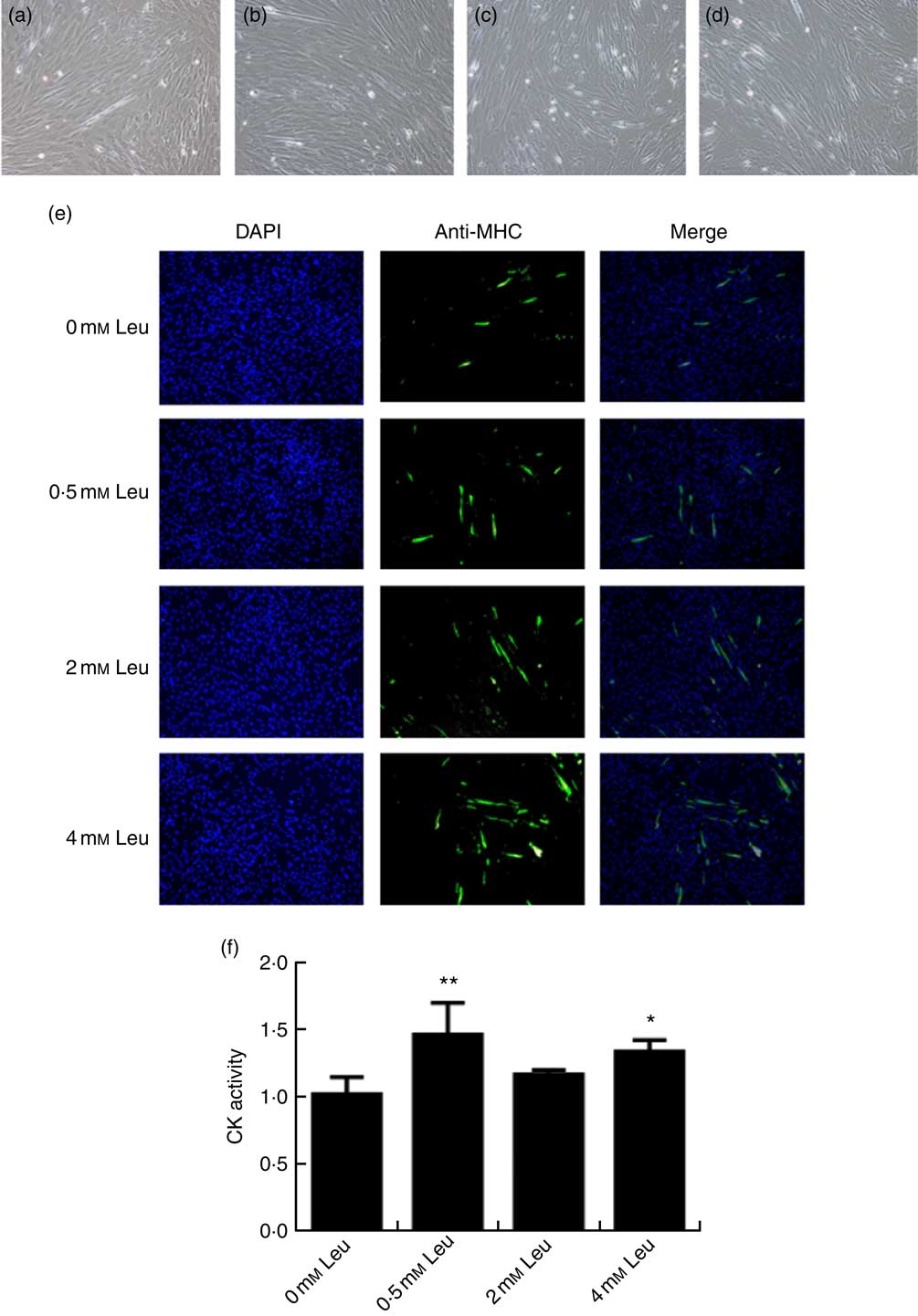

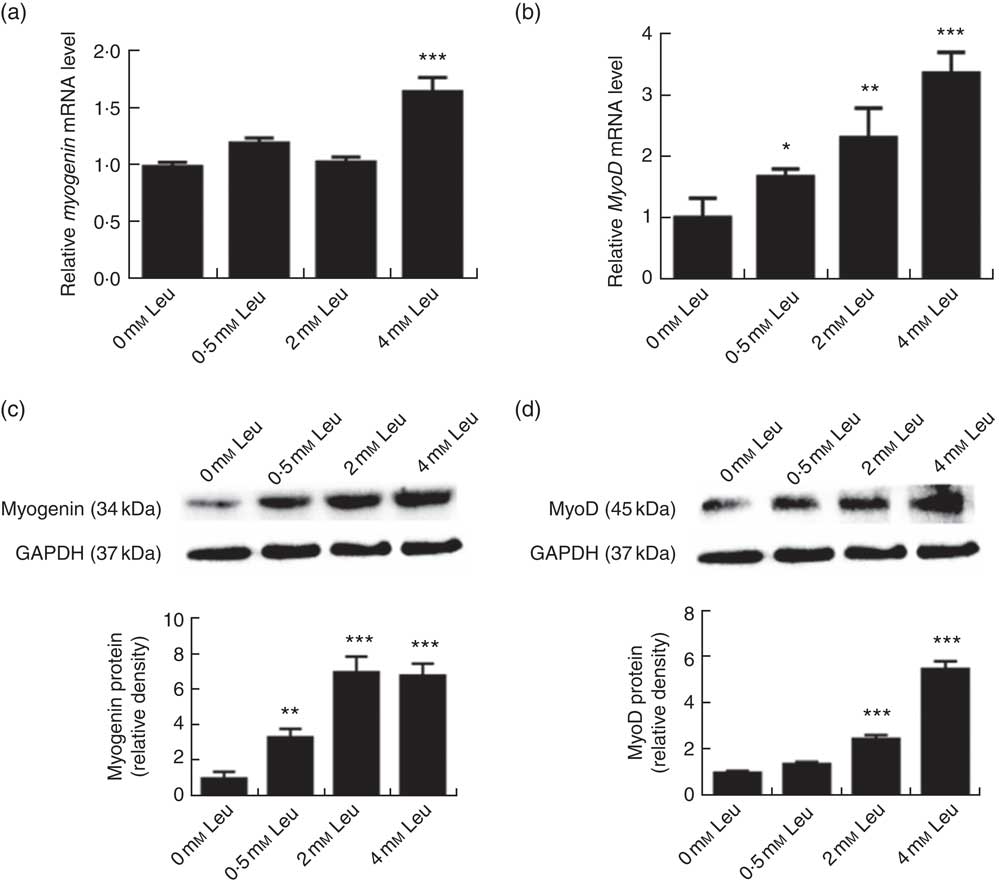

To explore the potential role of leucine on porcine myoblast differentiation, approximately 80 % confluent porcine myoblasts were induced to differentiate with differentiation medium containing 0, 0·5, 2 or 4 mm leucine for 3 d. As shown in Fig. 1(a)-(d), leucine induced the porcine myoblast morphological change. In addition, leucine increased the number of MHC-positive cells (Fig. 1(e)). CK activity is a well-described indicator of differentiation, and thus we next detected the effect of leucine on the level of CK. As shown in Fig. 1(f), CK activity was increased after leucine treatment in differentiating cells. Similarly, leucine increased the mRNA levels of myogenin and MyoD (Fig. 2(a) and (b)). Leucine also increased the protein levels of myogenin and MyoD (Fig. 2(c) and (d)). These results indicated that leucine promotes porcine myoblast differentiation.

Fig. 1 Leucine promotes myotube formation and increases creatine kinase (CK) activity. After the cells reached approximately 80 % confluence, porcine myoblasts were induced to differentiate with medium containing different concentrations of leucine for 3 d. Cells were observed under a phase-contrast microscope. (a) 0 mm leucine; (b) 0·5 mm leucine; (c) 2 mm leucine; (d) 4 mm leucine. Myosin heavy chain (MHC) expression (e) was analysed by immunofluorescence microscopy (4,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) staining also shown). CK activity (f) was analysed by microplate reader. Values are means, with their standard errors represented by vertical bars from three independent experiments. * P<0·05, ** P<0·01 as compared with negative control.

Fig. 2 Leucine up-regulates myogenin and myogenic determining factor (MyoD) expressions during porcine myoblast differentiation. After the cells reached approximately 80 % confluence, porcine myoblasts were induced to differentiate with medium containing different concentration of leucine for 3 d. The mRNA levels of myogenin (a) and MyoD (b) were determined by real-time quantitative PCR normalised to the amount of β-actin mRNA. Values are means, with their standard errors represented by vertical bars from three independent experiments performed in duplicate. Myogenin and MyoD protein levels (c, d) were determined by Western blot analysis. Equal loading was monitored with anti-glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) antibody. Mean values with their standard errors of the densitometry results from three independent experiments are shown in the lower panel. * P<0·05, ** P<0·01, *** P<0·001 as compared with negative control.

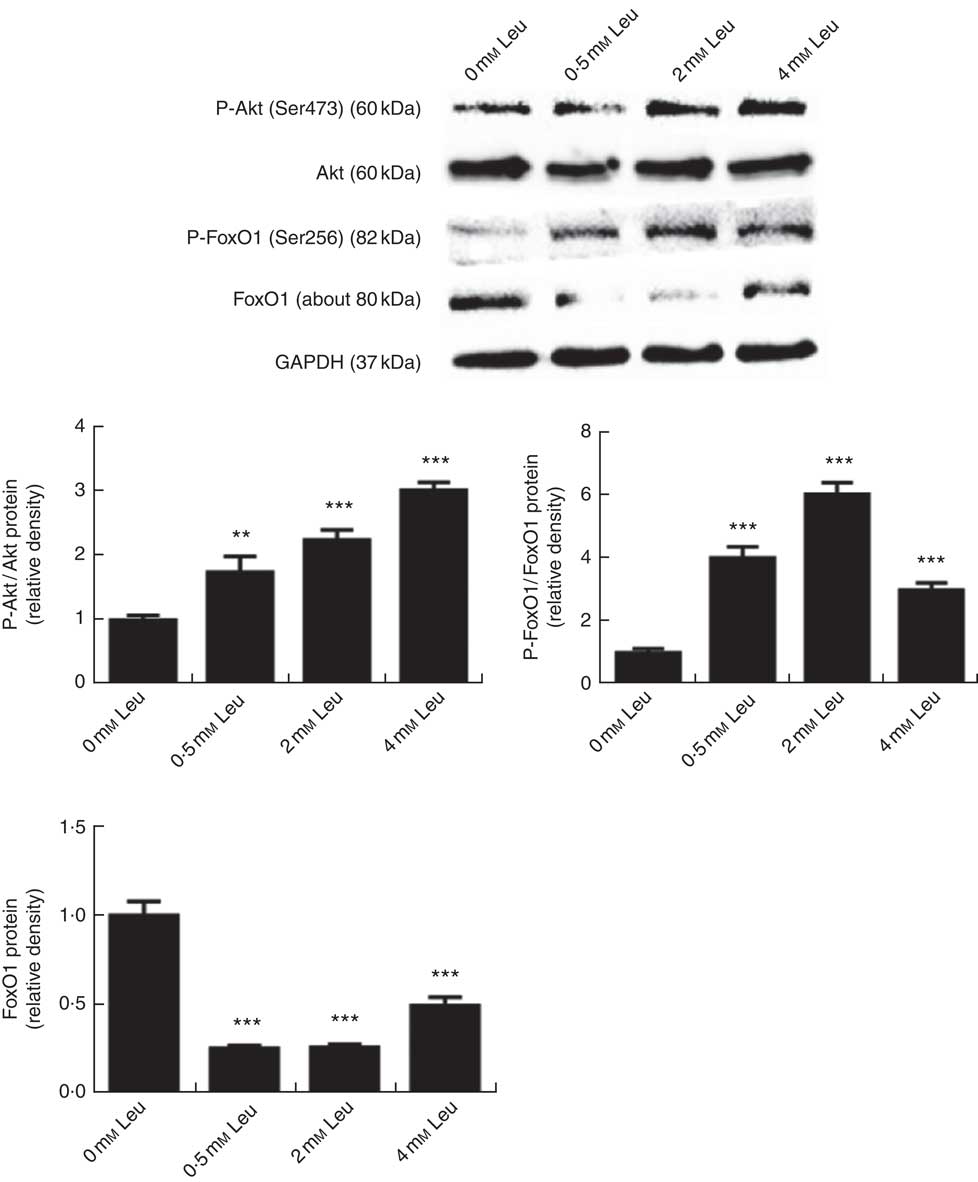

Leucine activates the protein kinase B/Forkhead box O1 signalling pathway

To investigate whether leucine can regulate the Akt/FoxO1 signalling pathway during porcine myoblast differentiation, we measured the levels of P-Akt/Akt, P-FoxO1/FoxO1 and FoxO1 protein after leucine treatment. As shown in Fig. 3, leucine increased the levels of P-Akt/Akt and P-FoxO1/FoxO1, as well as decreased the protein level of FoxO1, during porcine myoblast differentiation. The results indicated that leucine activates the Akt/FoxO1 signal pathway during porcine myoblast differentiation.

Fig. 3 Leucine activates the protein kinase B (Akt)/Forkhead box O1 (FoxO1) pathway during porcine myoblast differentiation. When the cells reached approximately 80 % confluence, porcine myoblasts were induced to differentiate with medium containing different concentrations of leucine for 3 d. Akt, phosphorylated Akt (P-Akt), phosphorylated FoxO1 (P-FoxO1) and FoxO1 protein levels were determined by Western blot analysis. Equal loading was monitored with anti-glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) antibody. Mean values with their standard errors of the densitometry results from three independent experiments are shown in the lower panel. ** P<0·01, *** P<0·001 as compared with negative control.

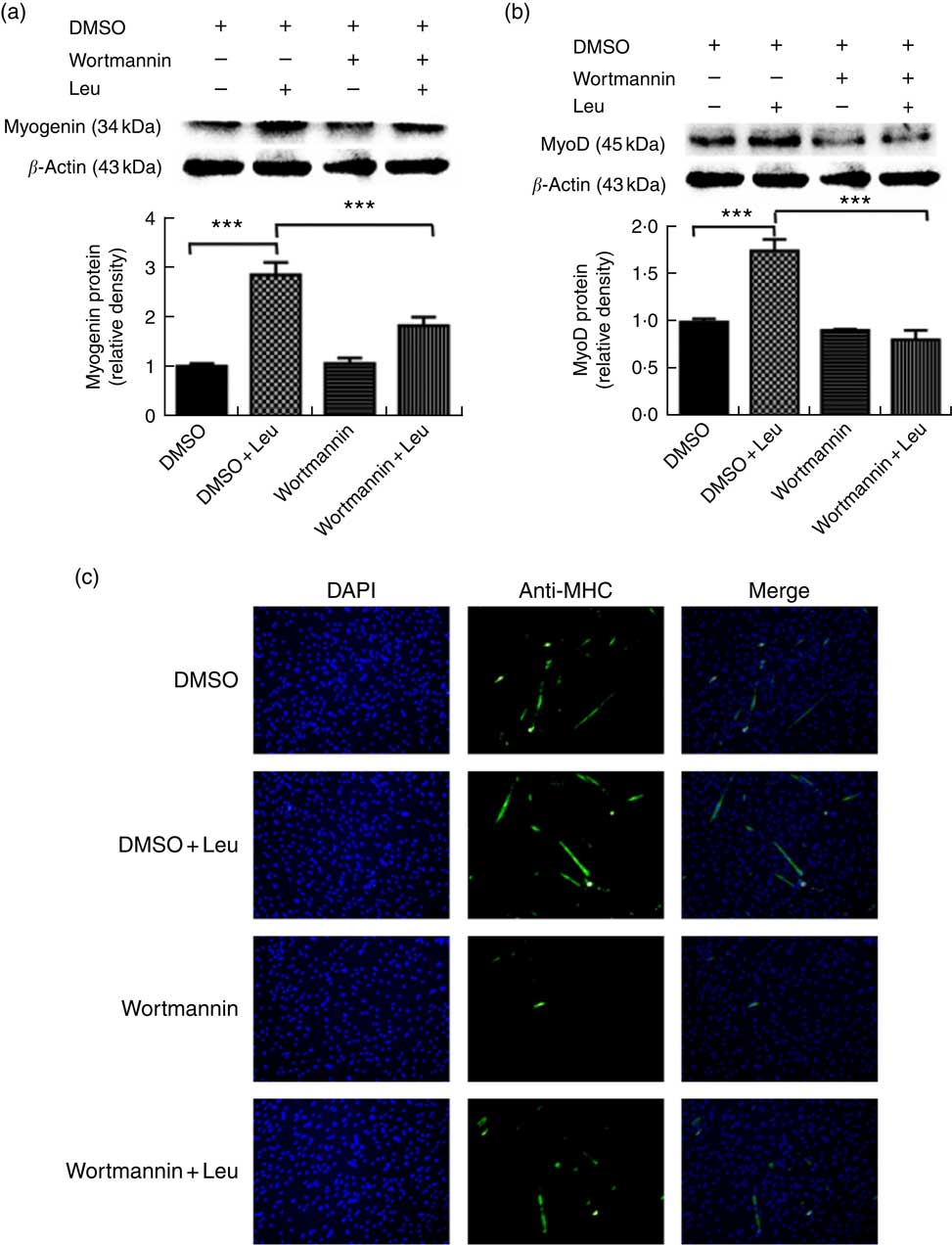

Leucine promotes porcine myoblast differentiation through the protein kinase B/Forkhead box O1 signalling pathway

Wortmannin, a specific repressor of the PI3K/Akt signalling pathway, could block the Akt ability to phosphorylate FoxO1 and then inactivate it. To investigate whether leucine promotes porcine myoblast differentiation via the Akt/FoxO1 pathway, 4 mm leucine and 1 µm wortmannin soluted in dimethylsulfoxide were added to the differentiation medium simultaneously. As shown in Fig. 4(a) and (b), leucine promoted the protein levels of myogenin and MyoD, whereas wortmannin attenuated the positive effect of leucine on muscle-specific gene expression. Moreover, the role of leucine on the number of MHC-positive cells was blocked when treating with wortmannin (Fig. 4(c)). In summary, our results indicated that leucine promotes porcine myoblast differentiation by the Akt/FoxO1 signalling pathway.

Fig. 4 Leucine promotes porcine myoblast differentiation through the protein kinase B (Akt)/Forkhead box O1 (FoxO1) signalling pathway. When the cells reached approximately 80 % confluence, porcine myoblasts were induced to differentiate with medium containing 4 mm leucine and 1 µm wortmannin for 3 d. Myogenin and myogenic determining factor (MyoD) protein levels (a, b) were determined by Western blot analysis. Equal loading was monitored with anti-β-actin antibody. Mean values with their standard errors of the densitometry results from three independent experiments are shown in the lower panel. Myosin heavy chain (MHC) expression (c) was analysed by immunofluorescence microscopy (4,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) staining also shown). *** P<0·001 as compared with negative control. DMSO, dimethylsulfoxide.

Discussion

Leucine, one of the branched-chain amino acids, plays a vital role in skeletal muscle protein turnover. Leucine is an anabolic factor that regulates muscle protein synthesis and degradation. It has been recently reported that leucine limitation represses the expression levels of MHC, myogenin and MyoD during C2C12 cell differentiation, and the differentiation process was also inhibited when leucine was removed in mouse satellite cells( Reference Averous, Gabillard and Seiliez 21 ). It has also been reported that leucine promotes the proliferation and differentiation of primary rat satellite cells( Reference Dai, Yu and Shen 22 ). In this study, we found that leucine stimulated myotube formation and increased CK activity during porcine myoblast differentiation. Moreover, leucine increased the expression of myogenic differentiation markers (MyoD and myogenin) at mRNA and protein levels. Our results proved that leucine promotes differentiation of porcine myoblasts, which is consistent with previous studies in murine muscle cells( Reference Averous, Gabillard and Seiliez 21 , Reference Dai, Yu and Shen 22 ).

Akt, a serine/threonine protein kinase, plays a critical role in regulating diverse cellular functions. In the present study, we found that leucine increased the level of P-Akt/Akt during porcine myoblast differentiation, indicating that Akt was activated by leucine. Increase of phosphorylation level of Akt by leucine was also observed in skeletal muscle of mice( Reference Ribeiro, Christofoletti and Pezolato 26 ). FoxO1, a downstream protein factor of the PI3K/Akt signalling pathway, can be phosphorylated by Akt directly and then results in inactivation( Reference Brunet, Bonni and Zigmond 27 , Reference Tran, Brunet and Griffith 28 ). Some studies suggest that FoxO1 may drive the formation of myotubes( Reference Bois and Grosveld 29 , Reference Hakuno, Yamauchi and Kaneko 30 ). However, in recent years, the vast majority of existing researches have reported that FoxO1 is a negative regulator during skeletal muscle differentiation( Reference Yuan, Shi and Liu 12 , Reference Accili and Arden 31 – Reference Xu, Chen and Chen 33 ). In this study, we showed that leucine increased the level of P-FoxO1/FoxO1 and decreased the protein level of FoxO1. Together with Fig. 1–3 in this study, it is most likely that leucine activated Akt, then phosphorylated the FoxO1 and finally promoted porcine myoblast differentiation. Indeed, we found that wortmannin, a specific repressor of the PI3K/Akt signalling pathway, has a strong impact on the role of leucine in porcine myoblast differentiation (Fig. 4).

In summary, our findings provided the first evidence that leucine promotes differentiation of porcine myoblasts and the Akt/FoxO1 signalling pathway may be involved in leucine-induced differentiation promotion.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (nos 31672432, 31272459).

X. C. and Z. H. conceived the study and designed the experiments. S. Z. carried out the experiments, analysed the data and wrote the manuscript. X. C., Z. H., D. C., B. Y., H. C., J. L. , J. H., P. Z. and J. Y. contributed reagents/materials/analysis tools. Z. H. revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.