Accumulating evidence suggests that childhood is a crucial period during which long-term healthy or unhealthy dietary habits are created and established that are commonly tracked into later in life(Reference Craigie, Lake and Kelly1). Unhealthy dietary habits could contribute to the development of obesity, type 2 diabetes mellitus, CVD and sub-optimal immunity in children(Reference Schroder2). Dairy products can be important in diversifying the diet as they are nutrient-dense and provide high-quality protein and micronutrients in an easily absorbable form that can benefit both nutritionally vulnerable people and healthy people when consumed in appropriate amounts(3). Dairy products constitutes a major source of dietary energy for children; it provides a plethora of nutrients to aid the body’s development and growth, especially in bone health(4). Specifically, dairy products such as cheese, yogurt and milk contain micronutrients (e.g. vitamin B and vitamin D), macronutrients (e.g. proteins) and enzymes; bioavailability of some nutrients, such as Ca, is high compared with that in other foods in the diet(4). Although there are no global recommendations for milk or dairy consumption (most developed countries recommend two-three servings per day for children and adolescents), an elevated percentage of schoolchildren worldwide are not meeting country-specific recommended daily intakes, especially among adolescents, which may lead to unfavourable long-term health implications(Reference Dror and Allen5,Reference Baird, Syrette and Hendrie6) . It has been suggested that there is a neutral or inverse association between dairy products consumption and indicators of obesity, hypertension and incidence of dental caries among schoolchildren(Reference Dror and Allen5,Reference Dror7,Reference Willett, Rockström and Loken8) , while a recent review proposes that dairy products do not play a significant role in the development of childhood obesity, although they do make a crucial contribution to children’s nutrient intake(Reference Dougkas, Barr and Reddy9). Scientific evidence indicated that dairy products are important for linear growth and bone health during childhood(Reference Dror and Allen5).

Studies among schoolchildren showed a favourable association between higher intake of dairy products and cardiorespiratory fitness (CRF)(Reference Moschonis, van den Heuvel and Mavrogianni10,Reference Moreno, Bel-Serrat and Santaliestra-Pasías11) .Available data indicated that in childhood higher dairy product intake was associated with higher intakes of fruits, vegetables and cereals(Reference Campmans-Kuijpers, Singh-Povel and Steijns12), while inadequate milk intake in adolescence was associated with skipping breakfast and consumption of processed foods(Reference Silva, Elias and Mais13). Moreover, a study in children suggested that those with less sedentary behaviours and increased physical activity (PA) consumed more dairy products(Reference Santaliestra-Pasías, González-Gil and Pala14).

The potential associations of dairy intake with metabolic (e.g. obesity and physical fitness (PF)) and lifestyle (e.g. diet, physical and sedentary activities) indices have not been studied in large, representative, country-wide studies in children.

Therefore, the present study aimed to explore the associations of recommended dairy product intake with several dietary habits, obesity, PF, PA, screen time and sleep taking into consideration several potential confounders, in an extensive, national representative sample of schoolchildren aged 8 to17 years.

Materials and methods

Study population

The data were derived from a population-representative, nationwide, school-based health survey in Greece, under the auspices of the Ministry of Education. We collected nutritional, anthropometric, PA, screen and sleep time and PF data along with information on age and sex. Children and adolescents (n 177 091, aged 8 to 17 years) from public and private schools participate in the study (participation rate was almost 40 % of the total student population of Greece). Parents were informed in writing for this school health survey and gave their written consent.

Assessment of demographic and anthropometric data

Demographic information of students (e.g. school, class, sex and date of birth) was obtained from the school records. Children’s body weight, height and waist circumference were measured in the morning using a standardised procedure. Specifically, body weight was measured in the standing upright position with electronic scales with a precision of 100 g (children wear little clothing). Standing height was determined to the nearest 0·5 cm with the child’s weight being equally distributed on the two feet, head back and buttocks on the vertical land of the height gauge. BMI was calculated as the ratio of body weight to the square of height (kg/m2). Waist circumference was measured at the midpoint between the lower margin of the least palpable rib and the top of the iliac crest, using a flexible measure to the nearest 0·1 cm. BMI status (e.g. normal-weight, overweight and obese) was classified using the International Obesity Task Force age- and sex-specific BMI cut-off criteria(Reference Cole, Bellizzi and Flegal15). Central obesity was defined as waist circumference:height ratio ≥ 0·5(Reference Browning, Hsieh and Ashwell16). Physical Education professionals performed all anthropometric measurements. Since the collected data were part of the obligatory school curriculum, students’ verbal informed consent was considered sufficient.

Assessment of physical fitness levels

The Euro-fit PF test battery was used to evaluate children’s PF levels(17). Given that PF constitutes a significant factor for a healthier life, the Euro-fit tests form a complete fitness package that evaluates strength, speed, muscle endurance, flexibility and cardiorespiratory endurance(17). The battery consists of five tests, i.e. (a) a multi-stage 20 m shuttle run test, to estimate aerobic performance; (b) a maximum 10 × 5 m shuttle run test to evaluate speed and agility; (c) a sit-ups test in 30 s, to measure the endurance of the abdominal and hip-flexor muscles; (d) a standing long jump, to evaluate lower body explosive power and (e) a sit and reach test to measure flexibility. All fitness tests were administered during the Physical Education class by Physical Education professionals, who were instructed through a detailed manual of operations and followed a standardised procedure of measurements to minimise the inter-rate variability among schools. Moreover, participants’ performance in PF tests was evaluated based on PF normative age- and sex-specific values for 6–18-year-old Greek boys and girls(Reference Tambalis, Panagiotakos and Psarra18). Specifically, for each of the five PF tests applied, a performance ≤ 25th percentile was considered as low between the 25th and 75th as average and ≥ 75th as high(Reference Tambalis, Panagiotakos and Psarra18).

Assessment of dietary habits

Children’s dietary, PA and sedentary habits were recorded via the use of an electronic questionnaire that was completed at school with the assistance of the teachers and/or Information Technology professors. Students’ dietary habits were assessed using the KIDMED (Mediterranean Diet Quality Index for children and adolescents)(Reference Serra-Majem, Ribas and Ngo19). This index contains sixteen YES or NO questions, including dietary habits that are under the principles of the Mediterranean diet (MD) dietary pattern and the general dietary guidelines for youth and habits that undermine them. Questions denoting a negative connotation concerning a high-quality diet are assigned a value of −1, while those with a positive aspect are assigned a value of +1. Thus, the total KIDMED score ranges from 0 to 12 and is classified into three levels: ≥ 8, suggesting an optimal adherence to the MD (sufficient dietary habits); 4–7, suggesting an average adherence to the MD and an improvement needed to adjust dietary intake to guidelines (relatively sufficient dietary habits) and ≤ 3, suggesting a low adherence to the MD and generally a low diet quality (insufficient dietary habits).

Dairy products consumption

Participants were characterised as ‘dairy products consumers’ if they answered the question ‘Takes two yogurts and/or some cheese and a cup of milk, daily’, based on whether they met current recommendations for milk or dairy consumption(Reference Dror and Allen5). Specifically, in the current study participants were characterised as ‘dairy products consumers’ if they consumed three servings, daily (e.g. two yogurts and/or 40 g cheese and a cup of milk, or three cups of milk, etc.). Participants who did not consume the above-mentioned quantities were characterised as ‘non-consumers.’ In most developed countries, the current recommendations for children and adolescents call for the consumption of two-three servings of dairy products per day(Reference Dror and Allen5).

Assessment of self-reported physical activity and sedentary time

Patterns of PA were also self-reported. The questionnaire used had been previously validated(Reference Grigorakis, Georgoulis and Psarra20) and included simple closed-type questions regarding children’s frequency, time and intensity of participation in (a) school-related PA (including activity during Physical Education classes; (b) organised sports activities and (c) PA during leisure time. Children who participated in moderate to vigorous PA for at least 60 min per day were considered as meeting the recommendations for PA.

Weekly time spent in sedentary activities (e.g. TV viewing, playing with the computer or/and console games and use of the Internet for non-study reasons) was also calculated for each student (via multiplying the weekly frequency of participation with the duration per bout of participation in sedentary activities). In the current study, screen viewing was used as a proxy for sedentary behaviours. Using the threshold of two hours per day, as per current guidelines, students were classified as sedentary or not, i.e. exceeding (>2 h/d) or not (≤ 2 h/d)(Reference Colley, Wong and Garriguet21).

Sleep time was self-reported. Children who were sleeping at least 9 h daily and adolescents who were sleeping at least 8 h daily were classified as meeting the recommendations for sufficient sleep. Children and adolescents sleeping less than the recommended hours were classified as having insufficient sleep(Reference Paruthi, Brooks and D’Ambrosio22).

Ethical approval

Ethical approval for the health survey was granted by the Ethical Review Board of the Ministry of Education and the Ethical Review Committee of Harokopio University.

Statistical analyses

Descriptive statistics were expressed as mean ± standard deviation or frequency (percentages). The χ 2 test evaluated associations between the categorical variables, and the Student’s t test were applied to evaluate differences in mean values of normally distributed variables. (The effect size for the t test for independent samples was calculated using Cohen’s d.) To assess the potential effect of several dietary habits on the ‘NO’ v. ‘YES’ recommended dairy products consumption, binary logistic regression analysis was implemented and OR with the corresponding 95 % CI were calculated, adjusted for confounders. Furthermore, aiming to assess the potential effect of several metabolic indices (e.g. total and central obesity and PF) and lifestyle factors such as screen time, sleeping time and PA on the category (NO or YES) of recommended dairy products consumption, hierarchical binary logistic regression analysis with Enter as the selected Method was implemented and OR with the corresponding 95 % CI were calculated to obtain adjusted association of covariates while controlling for confounding. The distribution of the independent variables in the models was done with scientific criteria. The Hosmer and Lemeshow’s goodness-of-fit test was calculated to evaluate the model’s goodness-of-fit, and residual analysis was implicated using the dbeta, the leverage and Cook’s distance D statistics to identify outliers and influential observations. All statistical analyses were performed using the SPSS version 23.0 software for Windows (SPSS Inc). The statistical significance level from two-sided hypotheses was set at P-value < 0·05.

Result

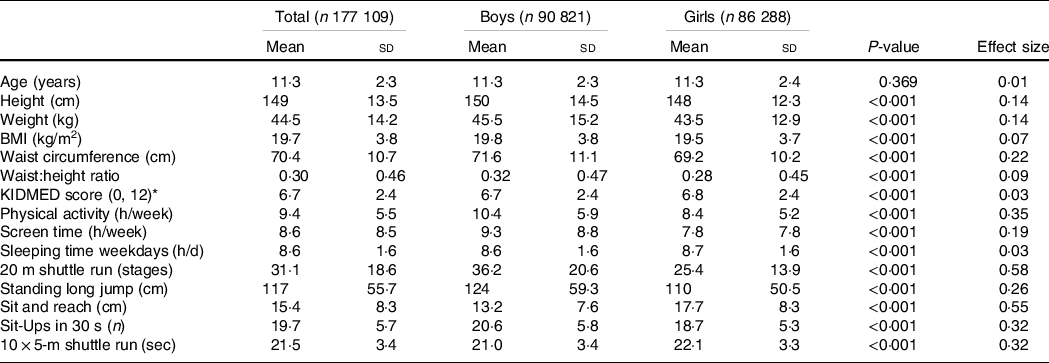

A total of 177 091 children and adolescents (aged 8 to 17 years) participated in the study. The majority (81·4 %) of them classified as dairy products consumers (81·2 % boys v. 81·5 % girls, P = 0·071). The proportion of girls meeting dairy products consumption recommendations declined with age, while we found a slight increase in dairy products intake with age among boys. Basic descriptive statistics of the total sample are presented in Table 1. Significant differences between girls and boys were recorded in anthropometric variables, dietary habits, PA, screen time and PF measurements (all P-values < 0·001).

Table 1. Baseline characteristics (mean ± sd) of the study participants

(Mean values and standard deviations)

* KIDMED score (≤ 3: insufficient dietary habits, 4–7: relatively sufficient dietary habits, ≥ 8: sufficient dietary habits. P-values and effect sizes for differences between boys and girls.

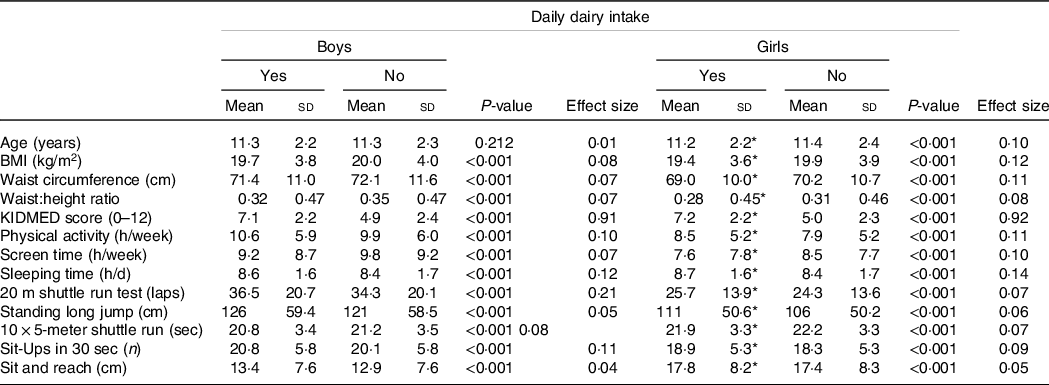

Dairy products consumers (Table 2) had better anthropometric and PF results, better KIDMED score, reduced screen time and more sleeping time in comparison with non-consumers of the same sex (all P-values < 0·001).

Table 2. Anthropometric and behavioural characteristics (mean ± sd) in the two dairy intake groups, in boys and girls (8 to 17 years)

(Mean values and standard deviations)

* P-values < 0·001 for differences between boys and girls dairy consumers.

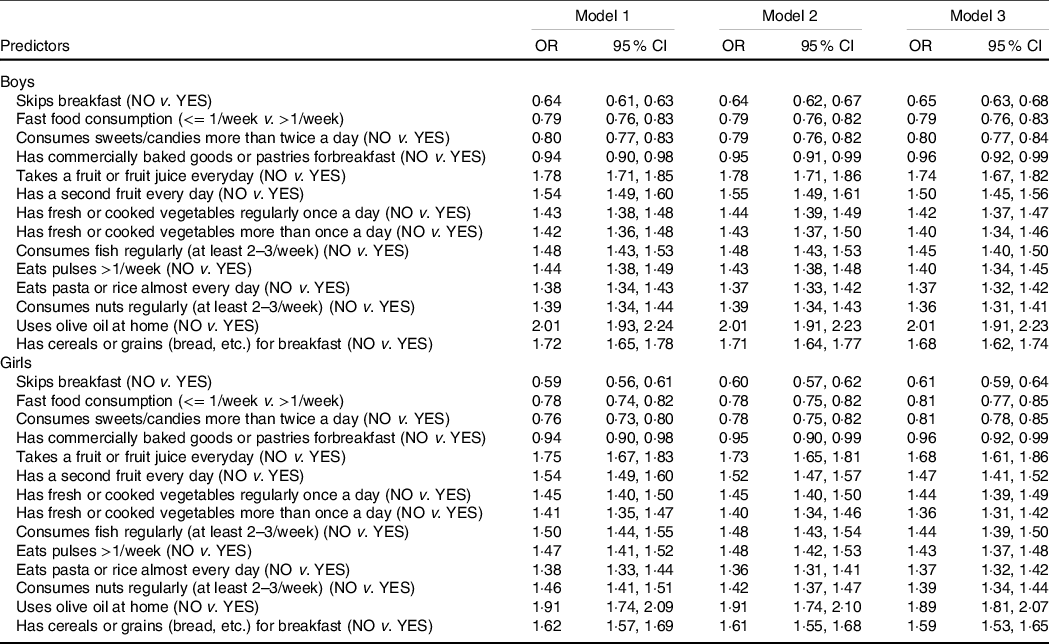

Unadjusted binary logistic regression analysis showed that being a dairy products consumer was associated with decreased odds of skipping breakfast, consuming fast food and sweets frequently and consuming baked goods or pastries for breakfast (negative dietary behaviours) and increased odds of eating fruits, vegetables, fish, pasta or rice regularly, pulses more than once weekly and uses olive oil at home (positive dietary behaviours) in both sexes (Table 3, model 1). After adjusting for covariates such as age, BMI and waist circumference, the recommended dairy product intake remained significantly associated with food habits previously reported (Table 3, model 2). Further adjustment for PA, screen and sleeping time did not significantly change the results (Table 3, model 3).

Table 3. Results from logistic regression models were used to evaluate the association of children’s (8 to 17 years) dietary habits with dairy products consumption (NO v. YES)

(Odd ratio and 95 % confidence intervals)

Model 1: unadjusted; model 2: adjusted for age, BMI and waist circumference; model 3: model 2 + screen time, sleeping hours and physical activity

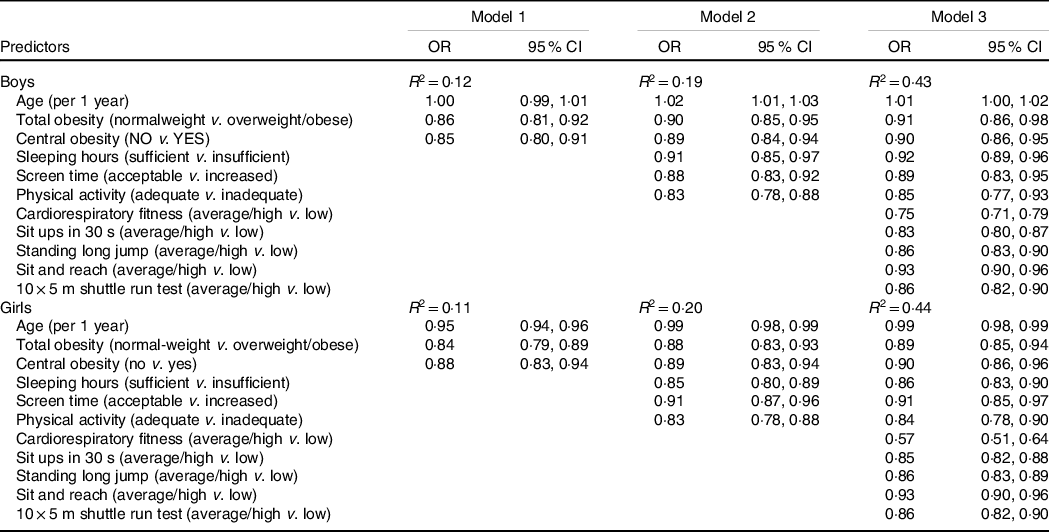

Taking into consideration that dairy products consumers had a healthier lifestyle profile in comparison with non-consumers, hierarchical binarylogistic regression analyses (3 models) were applied to explore the potential associations of included factors on recommended dairy product intake (NO v. YES) in both sexes. The initial analysis (Table 4, model 1) showed that being a dairy products consumer decreased the odds of being overweight/obese or centrally obese by almost 15 % in both sexes, adjusted for age and dietary habits. After further adjustment for inadequate (<60 min daily moderate to vigorous PA) PA levels, increased screen time (>2 h/d) and insufficient (<8–9 h/d) sleeping status (Table 4, model 2), the results showed that dairy consumers had lower odds for insufficient sleep by 8 % in boys and 14 % in girls, for inadequate PA levels by 15 % in boys and 16 % in girls and for increased screen time by 11 % in boys and 9 % in girls. Finally, when PF measurements were included in the analysis, it was shown that recommended dairy product consumers presented decreased odds of low PF than non-consumers in both sexes (Table 4, model 3), adjusted for KIDMED score. For example, boys and girls consuming recommended dairy products were 25 % (95 % CI: 0·71, 0·79) and 43 % (95 % CI: 0·51, 0·64) less likely to have low performances in CRF tests.

Table 4. Results from logistic regression models were used to evaluate the association of children’s (8 to 17 years) characteristics with dairy products consumption (NO v. YES)

(Odd ratio and 95 % confidence intervals)

R 2, R Square Nagelkerke; model 1: adjusted for age and BMI group and Central obesity and dietary habits; model 2: model 1 + screen time, sleeping hours and physical activity; Model 3: model 3 + physical fitness measurements levels.

Discussion

The most significant findings of the study are (a) schoolchildren from both sexes who were classified as dairy products consumers had less obesity, better CRF and strength and (b) recommended dairy products intake was associated with increased odds of healthy dietary habits (e.g. consumption of olive oil, fruits, vegetables and etc.), increased PA levels and adequate sleep.

The majority of the participants of this study (81·4 %) were characterised as dairy products consumers (consumed at least two yogurts and/or 40 g cheese and a cup of milk daily) with no differences found between sexes. Although there are differences in daily dairy recommendations among countries, it is considered that a significant percentage of schoolchildren fail to meet the recommended intake of dairy products(Reference Dror and Allen5). According to a review study, the proportion of schoolchildren meeting national dairy products consumption recommendations tends to decline with age through childhood and early adolescence(Reference Dror and Allen5), although males consume significantly more than females(Reference Dror and Allen5,Reference Baird, Syrette and Hendrie6) . In the current study, this is the case only for girls. To the contrary, we observed a slight increase in dairy products intake with age among boys. Potentially, factors not investigated in the present study could explain this finding.

Over the last few decades, several studies have proposed that increased consumption of dairy products may aid in the prevention of body weight gain and/or changes in body composition, while others found no significant association (at least among children) between dairy products consumption and body weight and/or fat percentages(Reference Dror and Allen5,Reference Baird, Syrette and Hendrie6,Reference Nezami, Segovia-Siapco and Beeson23,Reference Lu, Xun and Wan24) . Our findings showed that dairy products consumers had lower odds of total and central obesity by 10 %, in both sexes. Due to the inconsistent reports from scientific studies, dairy products continue to be the subject of intense debate concerning their potential association with obesity in children and adolescents(Reference Baird, Syrette and Hendrie6).

In the current study, recommended dairy intake was favourably associated with average/high PF levels, in both sexes, even after adjustment for several covariates. For example, boys and girls who consumed recommended dairy products were 25 % and 43 % less likely to have low performances in the CRF test, while participants from both sexes had 14 % lower odds for low performance in the explosive power test. These results are in agreement with findings of a favourable association between CRF and higher intake of milk(Reference Moschonis, van den Heuvel and Mavrogianni10) and higher consumption of dairy products with higher CRF in children and adolescents(Reference Moreno, Bel-Serrat and Santaliestra-Pasías11). Moreover, prospective data have shown a favourable association of milk consumption in childhood with physical performance later in life(Reference Birnie, Ben-Shlomo and Gunnell25). Numerous metabolically active nutrients naturally existing in dairy products such as proteins (especially leucine), and vitamins B2 and B12 could provide a basis for interpreting the independent association, at least in part, between dairy products intake and PF(Reference Lu, Xun and Wan24,Reference Manios, Moschonis and Dekkers26) . As dairy products intake has been previously presented to be part of a more favourable lifestyle pattern in children and adolescents(Reference Tambalis, Panagiotakos and Psarra27), increased PA levels recorded in the current study for schoolchildren with higher dairy products consumption could also provide a basis, but no explanation, for interpreting the favourable association between dairy products consumption and PF. Further study is required to confirm these associations.

Our results showed that dairy product consumers had increased odds of healthy dietary habits such as eating vegetables more than once a day, consuming fish, pasta or rice regularly, eating pulses more than once weekly and uses olive oil at home and lower odds of unhealthy dietary habits such as regular sweet consumption, frequent fast food intake and skipping breakfast. In line with the present results, a study among Dutch children and adolescents reported that higher dairy product consumption was associated with higher intakes of fruits, vegetables and cereals(Reference Campmans-Kuijpers, Singh-Povel and Steijns12). Moreover, a study among Brazilian adolescents aiming to identify factors associated with inadequate milk consumption reported that among others, skipping breakfast and consumption of processed foods were independently associated with inadequate milk intake(Reference Silva, Elias and Mais13). Also, the present study is in line with a study among Australian children which revealed that dairy intake was associated with higher intakes of bread, cereals, fruit and vegetables(Reference Rangan, Flood and Denyer28). Finally, a review study concluded that yogurt consumption is associated not only with dietary patterns and lifestyles (e.g. physically active ≥ 2 h/week) but also with better diet quality (e.g. higher consumption of fruits and vegetables and whole grains) and healthier metabolic profiles (e.g. body weight), while dairy consumers compared with low or non-consumers presented better compliance with dietary guidelines(Reference Panahi, Fernandez and Marette29). The previous findings suggest that the consumption of dairy products might be a marker for better diet quality.

Participants of the current study who consumed dairy products had lower odds of increased screen time (>2 h/d) and inadequate PA levels by 10 % and 15 %, respectively, than non-consumers. A recent study among European children suggested that those with a healthy lifestyle, especially regarding sedentary behaviours and PA over time, consumed more milk and yogurt(Reference Santaliestra-Pasías, González-Gil and Pala14). Among adolescents, inadequate milk intake was independently associated with physical inactivity(Reference Manios, Moschonis and Dekkers26), while results among young adults speculated that consumption of dairy foods significantly differed by PA level with the most active group consuming more servings per day for dairy products(Reference Jago, Nicklas and Yang30). Review studies proposed that schoolchildren exposed to higher advertising time and TV viewing were more predisposed to poorer diet quality(Reference Pettigrew, Jongenelis and Miller31,Reference Westerlund, Ray and Roos32) .

Dairy product consumers had lower odds of insufficient sleep duration (<8–9 h/d) by 11 % as compared with non-consumers. Dietary habits are significantly associated with sleep duration and may play a significant role in the mediation of the association between sleep and health among schoolchildren(Reference Kruger, Reither and Peppard33). A review study supports the notion that there is a relationship between short sleep duration and lower intakes of healthy foods(Reference Dashti, Scheer and Jacques34).

The study was performed in a wide range of ages (8 to 17 years), examined a very large part of the schoolchildren population and explored several covariates. Although dietary habits and PA were self-reported, the questionnaires that have been used had been previously validated in studies among children and adolescents(Reference Cole, Bellizzi and Flegal15,Reference Serra-Majem, García-Closas and Ribas35) . Moreover, regarding the KIDMED questionnaire, a recent study among Portuguese children and adolescents revealed that this index had an acceptable reproducibility and validity(Reference Rei, Severo and Rodrigues36).

Limitations include the fact that possible confounding factors, such as energy intake, ethnicity and socio-economic status, have not been evaluated. Moreover, because of the large sample size, statistical significance can easily be achieved (for this reason effect sizes were presented in Tables 1 and 2). Accordingly, our results could be interpreted with consideration of their practical or public health importance. Furthermore, the KIDMED score is not fully independent of dairy consumption. This is a cross-sectional, observational study, so causality cannot be assigned. Dietary habits, sleeping time and sedentary time were self-reported, therefore subject to desirable reporting bias. Nevertheless, participant responses were anonymous; as a result, they had no reason to misreport.

The results of this nationwide, representative health research in schoolchildren showed that recommended dairy products consumption was associated with better PF and lower odds of total and central obesity. Also, recommended dairy intake was associated with increased odds of healthy dietary habits such as consumption of olive oil, fruits, vegetables, increased PA levels and adequate sleep. This knowledge could be supportive of recommendations to ensure healthier dietary habits in children and adolescents.

Acknowledgements

All authors contributed to the study’s conception and design. Material preparation, data collection and analysis were performed by K. D. T., D. P., G. P. and L. S. S. The first draft of the manuscript was written by K. D. T., and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

There is no funding source.

All authors agree with the manuscript and declare that the content has not been published elsewhere.

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest. This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.