Infant feeding (breast-feeding and complementary feeding) may be important for a healthy weight in later life. However, results on complementary feeding as a determinant of overweight are still conflicting: a recent review(Reference Moorcroft, Marshall and McCormick1) concluded that there is not sufficient evidence for an association between the timing of introducing solids and obesity. Since then, two papers have been published that reported a clinically relevant association between the timing of the introduction of solids and childhood obesity(Reference Huh, Rifas-Shiman and Taveras2, Reference Seach, Dharmage and Lowe3). One proposed mechanism to explain the higher prevalence of obesity in children introduced early to solids is rapid infant weight gain after the introduction of solids. Results on the net increase in energy intake in children introduced to solids are controversial, but intake of fatty and sugary foods has been reported to be higher at 12 months in children introduced to solids early(Reference Grummer-Strawn, Scanlon and Fein4). However, reverse causality can be the cause: an alternative explanation is that infant weight gain precedes the introduction of solids. Indeed, an earlier study showed that one of the reasons for parents to introduce solids earlier than recommended is that their infant was big for their age(Reference Scott, Binns and Graham5).

Most studies reporting the association between the introduction of solids and infant weight gain defined infant weight gain as the difference in weight between two time points, and did not take into account that introduction of solids may be related to weight change before and after the introduction of solids to the infant's diet, which is important to confirm or reject the proposed mechanism.

The aim of the present study was to examine the association between the very early (before 3 months), early (between 3 and 6 months) and timely (beyond 6 months) introduction of solids and weight change in infancy and early childhood. We hypothesise that infants that were introduced to solids very early and early were already heavier before introduction than infants who were introduced to solids after the age of 6 months.

Methods

Study design and population

The present study was embedded in the Generation R Study, an observational cohort study that follows children from fetal life onwards(Reference Jaddoe, van Duijn and van der Heijden6). The Generation R Study was designed to identify early determinants of growth, development and health. Invitations to participate in the study were made to all pregnant mothers who had an expected delivery date between April 2002 and January 2006 and who lived in the study area (Rotterdam, The Netherlands) at time of delivery. The present study was conducted according to the guidelines laid down in the Declaration of Helsinki and all procedures involving human subjects were approved by the Medical Ethical Committee at Erasmus MC, University Medical Center Rotterdam. Written informed consent was obtained from all subjects.

Of the 7295 mother–infant pairs who were followed from birth, 5088 received the 12-month food questionnaire, because data collection on food started from 2003 onwards: 3643 (72 %) mothers completed this questionnaire. Excluded were twins (n 82), children born before 37 weeks of gestation (n 158) and children with less than four measurements on weight and height (n 219). Data of 3184 children were analysed.

Compared with those with missing information on the introduction of solids and those having less than four weight and height observations, mothers included in the present study were more often breast-feeding at 6 months (32·9 v. 26·9 %), highly educated (33·4 v. 21·8 %), more often had infants with a normal birth weight (85·0 v. 81·8 %), were more often native Dutch (67·7 v. 44·2 %), less often smoked during pregnancy (7·7 v. 12·5 %) (P< 0·001 for all) and more often had a normal weight, defined as a BMI ≥ 25 kg/m2 (75·9 v. 72·0 %, P< 0·01).

Measurements

Infant feeding

For the present study, we were interested in the age of the first introduction of any solids. At the child's age of 12 months, mothers reported in a questionnaire the age of the first introduction of the following foods(Reference Hulshof and Breedveld7): dairy products, porridge, bread, biscuits, crackers, baby cookies, pasta, meat products, vegetarian meat substitutes, fish, shellfish, vegetables, fruit, peanuts and nuts. Answer categories included ‘never given’, ‘between 0 and 3 months’, ‘between 3 and 6 months’, ‘between 6 and 9 months’ and ‘older than 9 months’, which was recoded into three categories: ‘0 to 3 months’, ‘3 to 6 months’, and ‘6 months or later’. The latter group adheres best to the feeding recommendations of the WHO and is therefore used as the reference group(8).

Anthropometrics

Length/height and weight were measured according to a standard schedule (1, 2, 3, 4, 6, 11, 14, 18, 24, 30, 36 and 45 months of age) and procedures by well-trained staff at each visit to the child health centre. Length was measured in the supine position to the nearest millimetre until the age of 14 months using a neonatometer, after which height was measured in standing position by a Harpenden stadiometer (Holtain Limited). Weight was measured using a mechanical personal scale (SECA). Weight change was defined as the increase or decrease in weight-for-length/height (WFH) z-score, which was calculated from a national reference using the Growth Analyzer program (Growth Analyzer version 3.5, 2007; Dutch Growth Research Foundation)(Reference Fredriks, van Buuren and Burgmeijer9).

Covariates

Potential confounders were maternal educational level, ethnicity, BMI, smoking during pregnancy, gestational age, child's birth weight, breast-feeding, history of (any) food allergy in the infant's first year of life and hospital admission during the first year after birth. Mother's educational level and ethnicity were asked at enrolment. Mother's BMI was calculated from self-reported pre-pregnancy weight and measured height at intake. Smoking during pregnancy was self-reported in a prenatal questionnaire. Birth weight and gestational age were obtained from medical records. Mothers reported in a postal questionnaire that was sent at 2 months after birth whether they gave breast-feeding, formula feeding or a combination of both. History of (any) food allergy in the infant's first year of life and hospital admission during the first year after birth were asked at 12 months after birth, and were taken into account because if these events took place in the first months after birth, they could have confounded the associations.

Statistical analyses

Differences in characteristics between mothers introducing solids before 3 or 6 months were compared with those of mothers introducing solids after 6 months using the χ2 test (categorical variables) or by ANOVA (continuous variables).

A mixed linear model (Proc Mixed in SAS) was performed with WFH z-score as an outcome. Linear splines for WFH change by age were created, which are useful when estimates for weight change are expected to differ between time periods. The knots for the splines were positioned according to the moments of solid introduction (i.e. 0–3, 3–6 and after 6 months), and set after the start of the introduction of solids (mid-point of each category), the following 3 months after the start point for introduction, the following period until 12 months, and after 12 months (Table 1). The four periods obtained with the splines were put in the model as time variables, and the WFH development from birth to preschool age was obtained with stratified analyses for each group of solid introduction.

Table 1 Time periods for weight change estimates

Residuals of the spline model were normally distributed with a mean difference of 0·01 (95 % CI − 1·91, 1·89) between the actual and predicted values of WFH z-score, and residuals did not vary over time (Pearson's r 0·001, P= 0·90) or for subgroups (i.e. breast-fed children, children of low socio-economic status).

Analyses were conducted using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences for Windows version 17.0 (SPSS, Inc.) and the Statistical Analysis Software package version 9.1 (SAS Institute).

Results

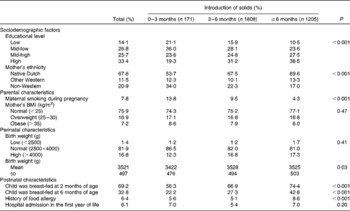

In the present study, 38 % of mothers introduced solids after the recommended age of 6 months. Relative to mothers who introduced solids before 3 or 6 months, mothers who introduced solids after 6 months were more often highly educated, native Dutch, non-smokers, breast-feeding for at least 6 months and had more often an infant with a history of food allergy. Hospital admission and mother's weight were not significantly associated with the timing of the introduction of solids. The number of children with either a low or high birth weight did not differ between the groups, but the mean birth weight of children who were introduced to solids before 3 months was slightly lower than children introduced to solids after 3 or 6 months (Table 2).

Table 2 Characteristics of 3184 participants according to the timing of the introduction of solids*

* Missing data were as follows: 99 (3·1 %) for educational level; 58 (1·8 %) for ethnicity; 532 (16·7 %) for maternal smoking; 698 (21·9 %) for mother's BMI; 3 (0·1 %) for birth weight; 87 (2·7 %) for breast-feeding at 2 months; 56 (1·8 %) for breast-feeding at 6 months; 172 (5·4 %) for history of allergy; 199 (6·3 %) for hospital admission.

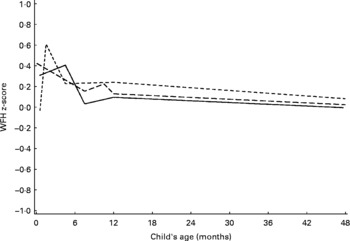

Table 3 shows the growth pattern from birth to preschool age for each group of solid introduction. Children who were introduced to solids very early (before 3 months) had a WFH change as expected (i.e. WFH z-score about 0) before they were introduced to solids. This was followed by a relative decrease in WFH until 4·5 months, but after 4·5 months, they were growing as expected (i.e. WFH z-score about 0). Children who were introduced to solids early (between 3 and 6 months) had a high WFH gain before they were introduced to solids (z= 0·65, 95 % CI 0·34, 0·95), but once introduced to solids, this was followed by a relative decrease in WFH (z= − 0·13, 95 % CI − 0·18, − 0·08). After 7·5 months, they were growing as expected with WFH z-score about 0 (Table 2; Fig. 1). Children introduced to solids according to the recommendation (after 6 months) had a small decrease in WFH before they were introduced to solids (z= − 0·04, 95 % CI − 0·05, − 0·03), but after the introduction of solids, they followed a growth pattern as expected (i.e. WFH z-score about 0).

Table 3 Weight-for-height change before, shortly after and after solid introduction, and after 12 months of age for children introduced to solids very early (n 104), early (n 1120) and timely (n 771)

* Adjustments were made for mother's educational level, ethnicity, smoking during pregnancy, mother's BMI, breast-feeding, history of allergy and hospital admission in the first year of life.

Fig. 1 Estimated weight-for-height (WFH) z-score for each age group of introduction to solids (this figure is a graphic presentation of the data in Table 3). ![]() , 0–3 months;

, 0–3 months; ![]() , 3–6 months;

, 3–6 months; ![]() , >6 months.

, >6 months.

At 4·5 months, children in the very early and early introduction of solid groups were on average 0·5 kg heavier than children introduced to solids timely (Table S1 and Fig. S1, available online).

Because the exact timing of the history of food allergy and hospitalisation is unknown, these variables could be either confounders or mediators. We have therefore run the models without these variables (Table S2, available online), but the results did not change.

Fig. 1 shows WFH z-score development from birth to preschool age, and is a graphical representation of Table 3. At the ending age (preschool age), WFH z-scores were 0·01 (95 % CI − 0·18, 0·19) for children introduced to solids very early, 0·11 (95 % CI 0·05, 0·17) for children introduced to solids early and 0·04 (95 % CI − 0·03, 0·11) for children introduced to solids according to the recommendation.

Discussion

The present study shows that children introduced early, but not very early, to solids had a higher increase in WFH before the introduction of solids than children introduced timely to solids. Differences in weight change disappeared during the first year of life. At preschool age, children introduced to solids early had a slightly higher WFH than children introduced to solids very early or timely.

Studying the association between the early introduction of solids and weight gain is quite a methodological challenge. First, the association between the early introduction of solids and weight gain may be subject to reverse causality: infants experiencing rapid weight gain may be earlier, or later, introduced to solids. Therefore, some studies adjusted the analyses for birth weight. However, this does not take the rate of weight gain shortly after birth into account. The present results revealed no significant differences in birth weight z-score among the subgroups, but showed that infants who were introduced early to solids were already heavier before the introduction of solids. Second, the association between the early introduction of solids and weight gain may be confounded by several factors. Although the associations were adjusted for the most important confounders, no detailed information was available on breast-feeding exclusivity, i.e. breast-feeding with no other fluids or solids at all. We also did not have detailed information on the exact amount of formula feeding and solid intake, and therefore not on exact energy and protein intake. This may have caused bias in any direction, but is most likely to affect weight change after the introduction of solids. However, this may not change our conclusion that children introduced to solids early were heavier before any solids were introduced. The timing of the introduction of solids was based on the 12-month FFQ. This could have induced some recall bias. However, there is no reason to assume that the recall differed according to weight change. Lastly, 72 % of participants returned the 12-month FFQ. Although this response rate is relatively high, mothers included in the analyses were generally healthier and wealthier, which was also reflected in the mean z-scores being above 0. However, we think it is unlikely that this has led to selection bias as we assume the missing data being ‘missing at random’, which means that the missing data depend on covariates in the model only. Selection bias would, for example, occur when children of less healthy or wealthy families had more often missing data but were also introduced to solids earlier than recommended and had a higher WFH after the introduction of solids.

Despite the use of different cut-off points to define the early introduction of solids, the present findings that solid introduction is associated with weight during the first months of life are consistent with other studies. Baker et al. (Reference Baker, Michaelsen and Rasmussen10) reported that infants introduced to solids before 4 months of age had a higher weight gain from birth to 1 year. Baird et al. (Reference Baird, Poole and Robinson11) found that children introduced to solids after 6 months were lighter and shorter than children introduced to solids before that age. One study included several measurement points and used a similar cut-off point as in the present study (at 3 months), making this study best comparable to ours. Infants receiving solids before 12 weeks were heavier at 4, 8, 13 and 26 weeks of age, but not at 52 weeks or later(Reference Forsyth, Ogston and Clark12). There is also one trial that found no weight differences at 3, 6 and 12 months in children introduced to solids at 3–4 months of age compared with children introduced to solids at 6 months(Reference Mehta, Specker and Bartholmey13). Wright et al. (Reference Wright, Parkinson and Drewett14) found that babies who were heavier at 6 weeks and 3 months were weaned earlier, but that infant weight gain between birth and 6 weeks was a stronger predictor. Also, Wright et al. in their study asked mothers for their reasons starting introduction of solids, and ‘my baby seems hungry’ was a predictor of early weaning. Thus, our hypothesis that infants are heavier before the introduction of solids, making mothers believe it is necessary to introduce solids, fits well in the present findings and the findings from the current literature.

After 1 year of age, we found no differences in weight change between children introduced to solids very early or early and children introduced to solids timely. However, as a result of differences in weight change during the first year of life, children introduced to solids early had a slightly higher WFH z-score compared with children introduced to solids according to the recommendation. This result is consistent with a study describing that early introduction of solids before 4 months of age is not associated with weight change adjusted for height between birth and age 3 years(Reference Griffiths, Smeeth and Hawkins15). However, associations between the early introduction of solids (defined either as continuous variables or before the age of 4 months) and weight status after 1 year of age have been reported at several ages, ranging between 3 and 40 years old(Reference Huh, Rifas-Shiman and Taveras2, Reference Seach, Dharmage and Lowe3, Reference Wilson, Forsyth and Greene16, Reference Schack-Nielsen, Sorensen and Mortensen17). In two of these studies, an association was not found between the introduction of solids before 4 months of age and weight in the same cohort at an earlier age(Reference Wilson, Forsyth and Greene16, Reference Schack-Nielsen, Sorensen and Mortensen17). Huh et al. (Reference Huh, Rifas-Shiman and Taveras2) adjusted their analyses for weight gain between 0 and 4 months of age, and this hardly influenced the association between the early introduction of solids and overweight at age 3 years. They also reported that the association was only present in formula-fed children. We have stratified our analyses according to the type of milk feeding to reveal possible effect modification, but our conclusions do not change (Tables S3(a)–(c), available online). We hypothesise that the early introduction of solids may therefore be associated with characteristics that determine later overweight. These characteristics may be related to lifestyle or may be related to biological programming. Grummer-Strawn(Reference Grummer-Strawn, Scanlon and Fein4), for example, found that children introduced to solids before the age of 4 months were more likely to have a higher intake of fatty and sugary food at 1 year of age.

In conclusion, although prior size may be related to the introduction of solids, we have found no evidence that early introduction of solids increases WFH. Infant weight change may therefore not be one of the underlying causal mechanisms for the association between the early introduction of solids and later overweight.

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge the contribution to this study of the participating general practitioners, hospitals, midwives and pharmacies in Rotterdam. This study was supported by a grant from the Netherlands Organization for Health Research and Development (ZonMW), no. 7110.0002, and an additional grant from the European Container Terminals (ECT) B.V. The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest. The authors' contributions are as follows: L. v. R., J. C. K.-d. J., H. A. M. and H. R. had a role in the conception and design of the study; L. v. R., J. C. K.-d. J. and C. W. N. L. performed the statistical analysis and wrote the manuscript; J. P. M., V. W. V. J., A. H. and A. C. S. H.-K. provided comments and consultations regarding the analyses and manuscript; H. A. M., H. R., J. P. M., V. W. V. J. and A. H. had a role in the acquisition of the data. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Supplementary tables and figure are available online at http://www.journals.cambridge.org/bjn